DISEASES OF THE

FEMALE GENITAL

TRACT

Part two

Endometrial Hyperplasia

This is an exaggerated endometrial proliferation

induced by sufficiently prolonged excess of

estrogen relative to progestin.

The severity of hyperplasia is classified according

to two parameters

a. architectural crowding of the glands &

b. cytologic atypia.

Accordingly there are three categories

1. Simple hyperplasia

2. Complex hyperplasia

3. Atypical hyperplasia

These three categories represent a spectrum based

on

the level and duration of the estrogen excess.

The risk of developing carcinoma depends on the

severity of the hyperplastic changes and associated

cellular atypia.

Simple hyperplasia carries a

negligible risk

, while a

woman with

atypical hyperplasia has a 20% risk of

developing endometrial carcinoma

.

Thus When atypical hyperplasia is discovered, it

must be carefully evaluated for the presence of

cancer and must be monitored by repeated

endometrial biopsy.

Any

estrogen excess

may lead to hyperplasia.

Potential contributors include

1. Failure of ovulation, e.g. around the menopause

2. Prolonged administration of estrogenic steroids

3. Estrogen-producing ovarian lesions such as

a. polycystic ovaries (Stein-Leventhal syndrome)

4. Obesity, because adipose tissue processes steroid

precursors into estrogens.

• A 45-year-old female has had menorrhagia

for the past 3 months. An endometrial

biopsy shows a rather mild degree of

endometrial hyperplasia. Which of the

following conditions most likely helped to

produce the findings in this case?

1-Ovarian mature cystic teratoma

2-Chronic endometritis

3-Failure of ovulation

4-Pregnancy

5-Use of oral contraceptives

Gross features

In

simple hyperplasia

the endometrium is

diffusely thickened .

In

complex & atypical hyperplasia

there is

usually

focal thickening

of the

endometrium.

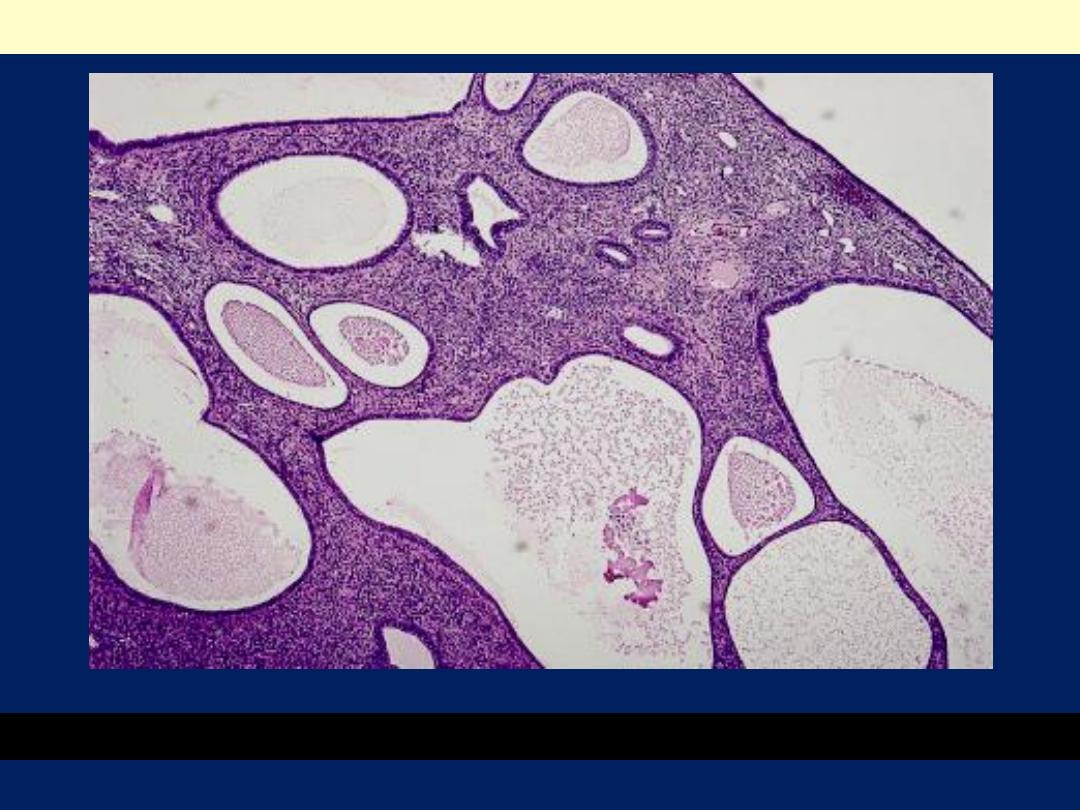

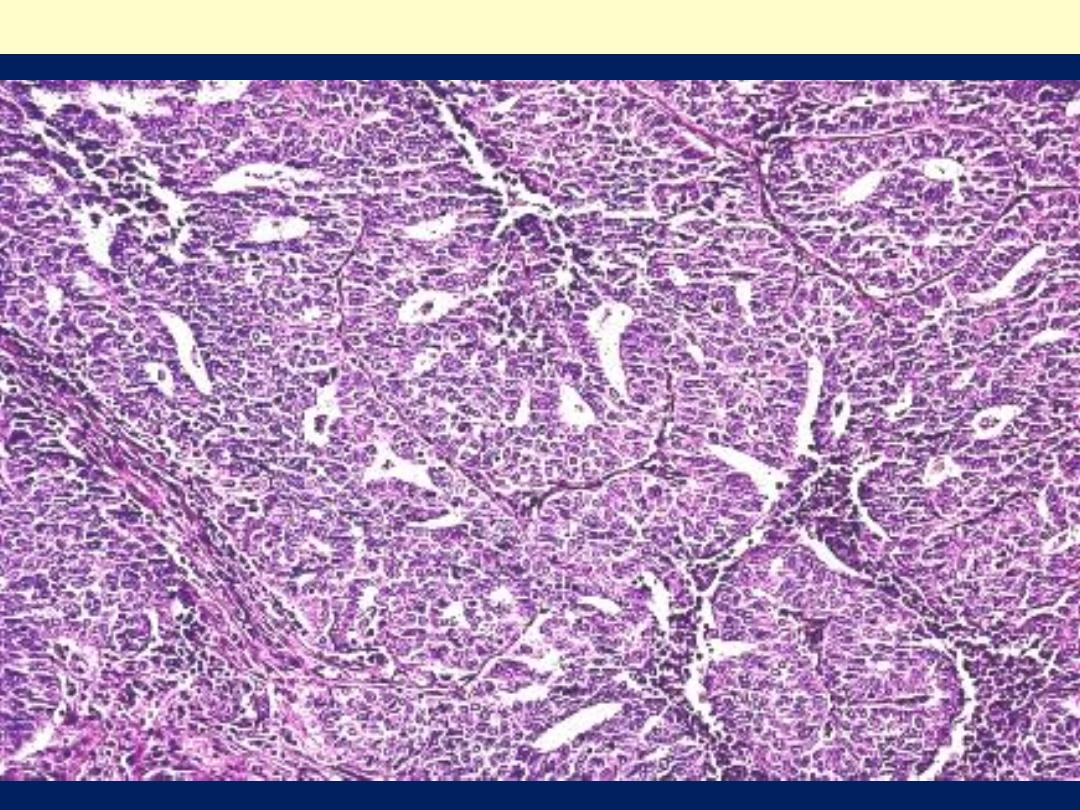

Simple hyperplasia without atypia, also known as cystic

or mild hyperplasia, is characterized by glands of

various sizes and irregular shapes with cystic dilatation.

There is a mild increase in the gland-to-stroma ratio.

The epithelial growth pattern and cytology are similar to

those of proliferative endometrium, . These lesions

uncommonly progress to adenocarcinoma

approximately 1%)

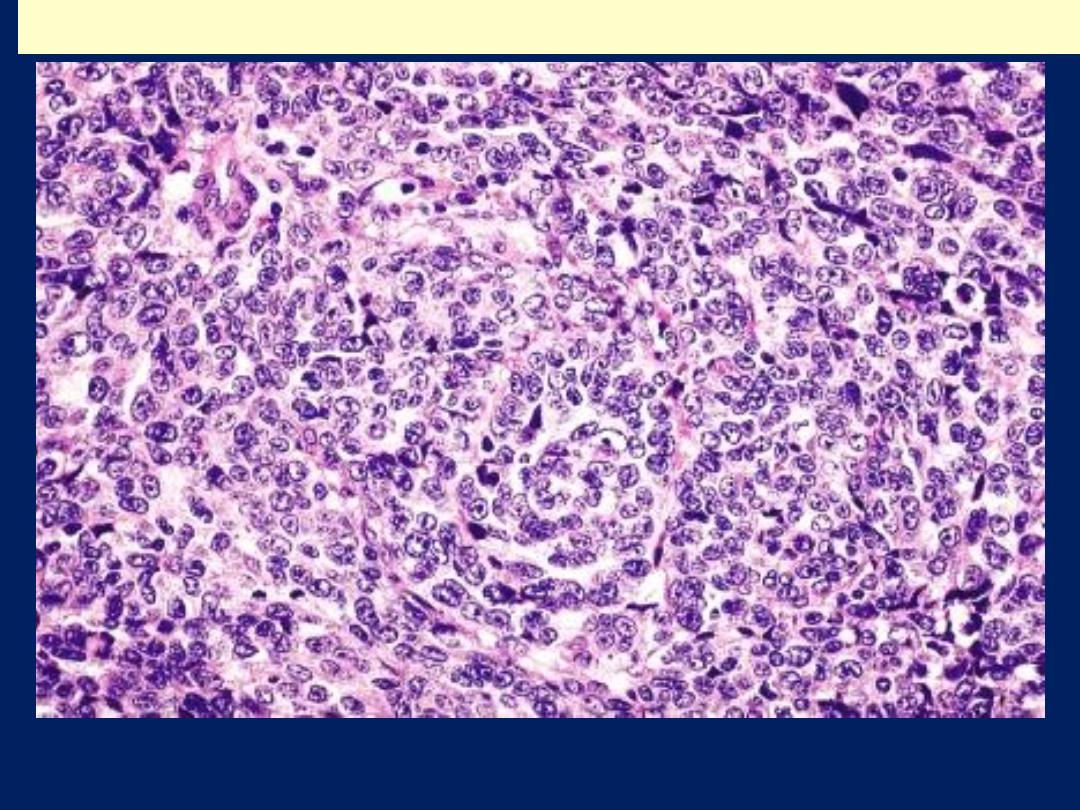

Simple hyperplasia with atypia is uncommon.

Architecturally it has the appearance of simple

hyperplasia, but there is cytologic atypia within the

glandular epithelial cells, as defined by loss of polarity,

vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli.

Approximately 8% of such lesions progress to

carcinoma.

Complex hyperplasia without atypia shows an increase in the

number and size of endometrial glands, marked gland

crowding, and branching of glands. the glands may be

crowded back-to-back with little intervening stroma .

However, the glands remain distinct and the epithelial cells

remain cytologically normal. This class of lesions has about a

3% progression to carcinoma,

Complex hyperplasia with atypia has considerable

morphologic overlap with well-differentiated endometrioid

adenocarcinoma and an accurate distinction between

complex hyperplasia with atypia and cancer may not be

possible without hysterectomy It has been found that

approximately 23% to 48% of women with a diagnosis of

complex hyperplasia with atypia have carcinoma when a

hysterectomy is performed shortly after the endometrial

biopsy or curettage.

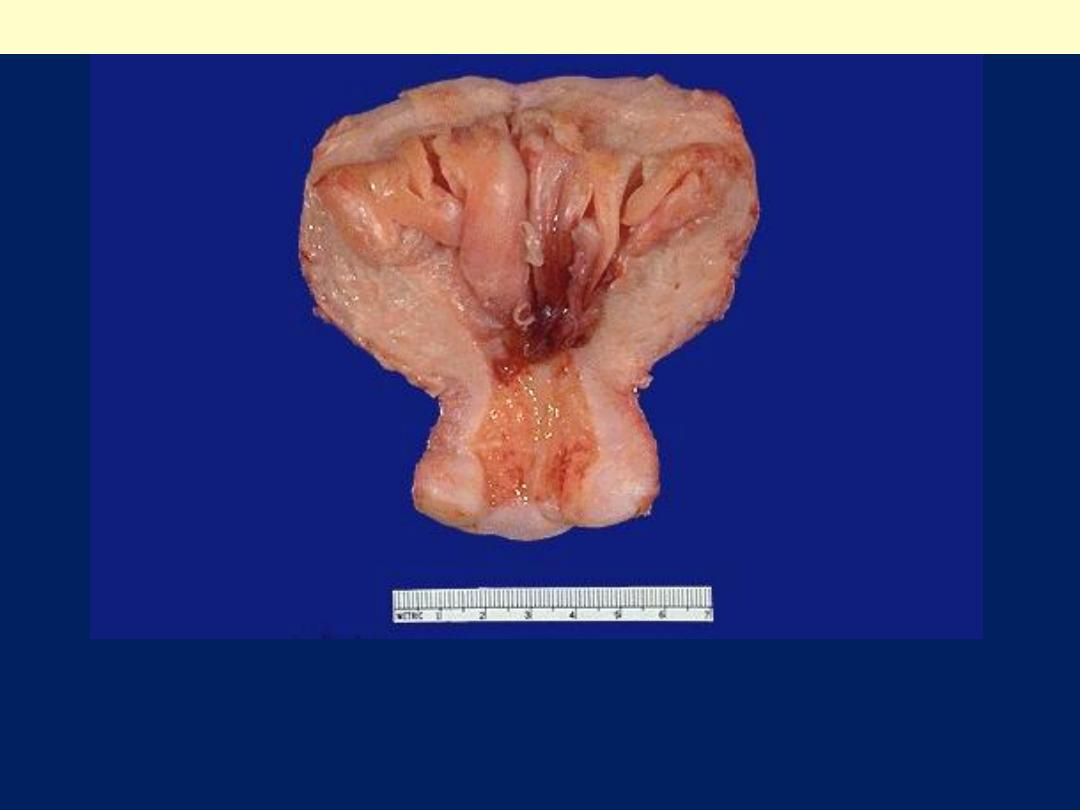

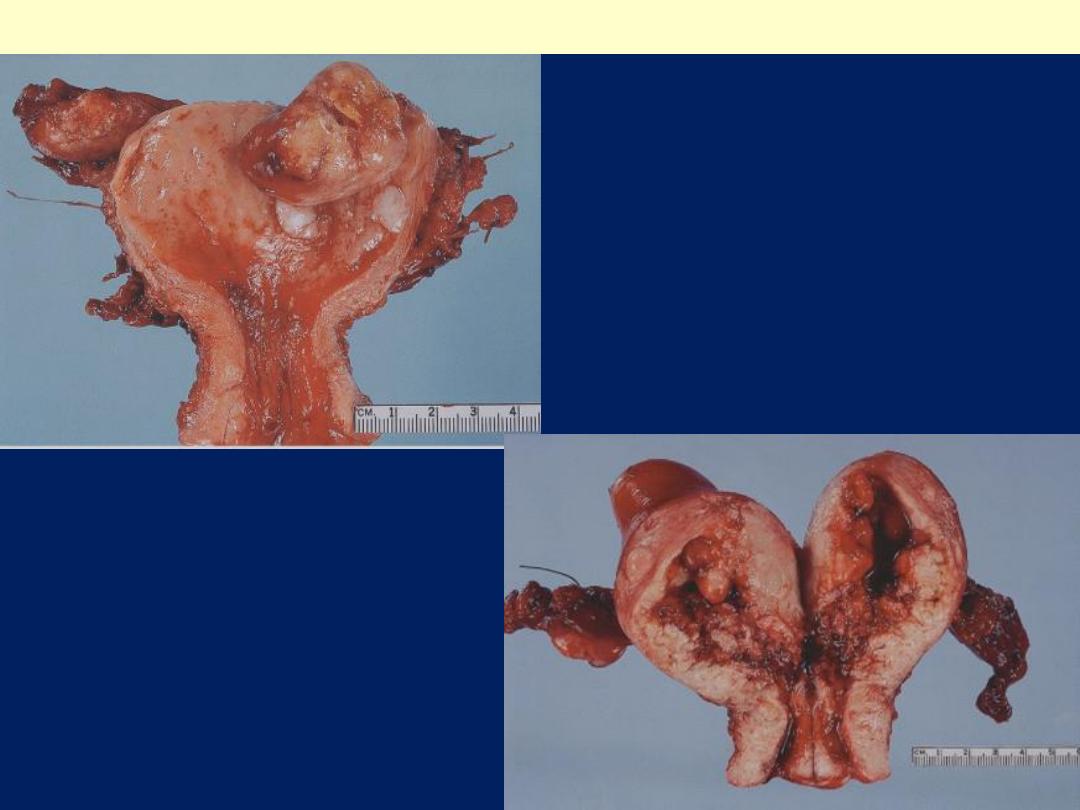

The prominent thickened folds of endometrium in this uterus

(opened to reveal the endometrial cavity) are an example of

hyperplasia.

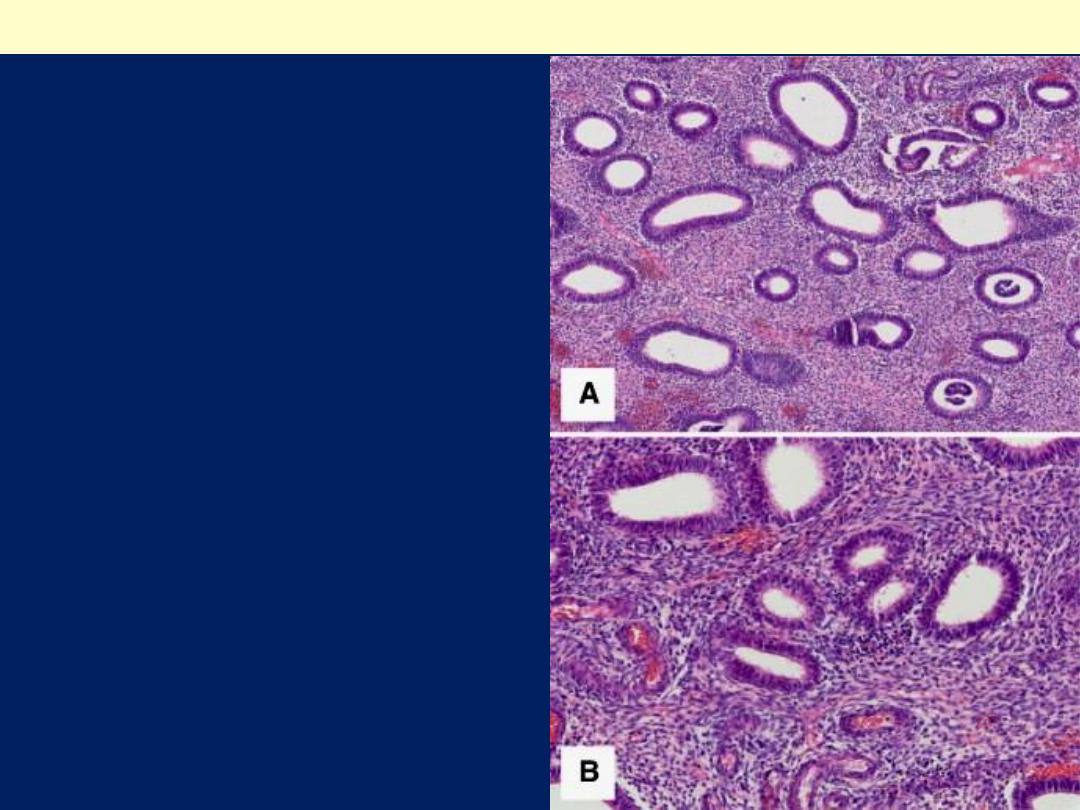

Diffuse endometrial hyperplasia

Closely packed

endometrial glands with

irregular distribution,

separated by abundant

endometrial stroma (A).

Glands are lined by

proliferative-type

endometrial epithelium

without atypia (B).

Complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia

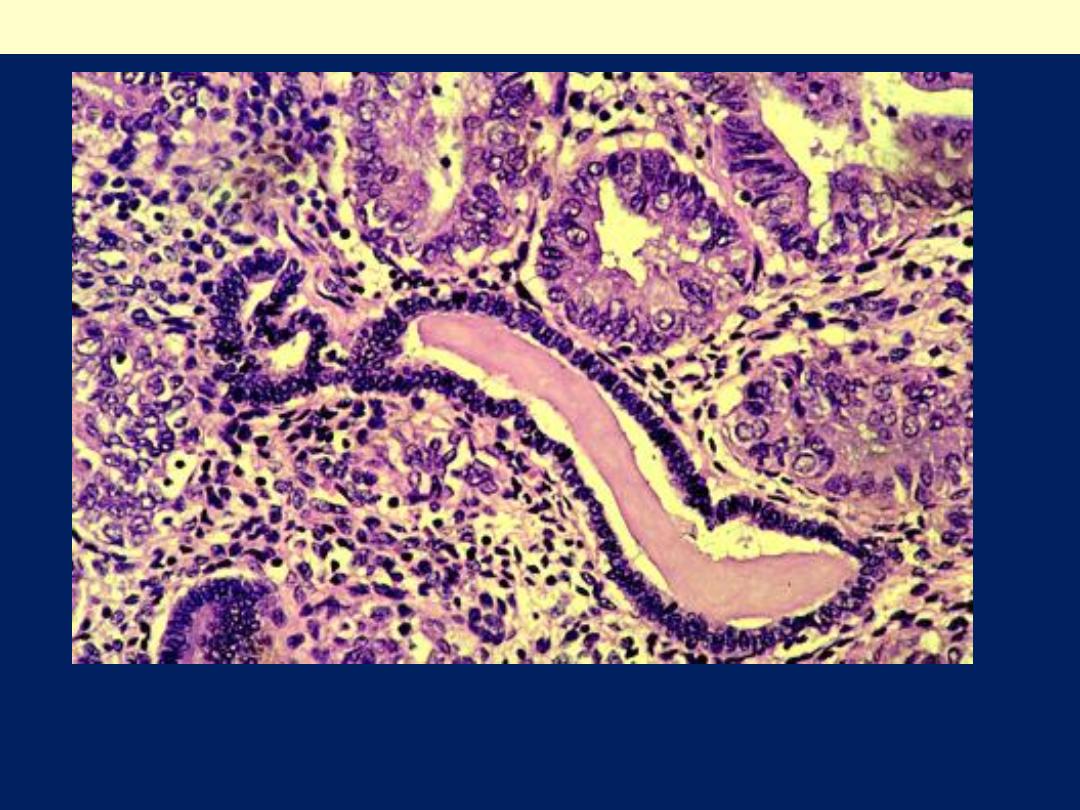

Nuclear and cytoplasmic differences are present between

atypical glands (upper Rt.) and residual normal endometrial

glands (center).

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia

Tumors of the Endometrium and

Myometrium

The most common neoplasms of the body of

the uterus are

1. Endometrial polyps,

2. Smooth muscle tumors.

3. Endometrial carcinomas.

All tend to produce

bleeding

from the uterus

as the earliest manifestation.

Endometrial polyp

Huge endometrial polyp filling the

endometrial cavity. There is also a smaller

endocervical polyp and a subserosal

leiomyoma.

The uterus has been opened anteriorly

through cervix and into the endometrial cavity.

High in the fundus and projecting into the

endometrial cavity is a small endometrial

polyp. Such benign polyps may cause uterine

bleeding.

•

Endometrial polyps are exophytic masses of

variable size that project into the endometrial

cavity. They may be single or multiple and are

usually sessile, measuring from 0.5 to 3 cm in

diameter, but are occasionally large and

pedunculated. Polyps may be asymptomatic or

may cause abnormal bleeding (intramenstrual, or

postmenopausal) if they ulcerate or undergo

necrosis. Most commonly the glands within polyps

are hyperplastic or atrophic, but they can

occasionally demonstrate secretory changes

(functional polyps) . Atrophic polyps, which largely

occur in postmenopausal women, most likely

represent atrophy of a hyperplastic polyp. Rarely,

adenocarcinomas arise within endometrial polyps

.

Cystically dilated glands and a fibrous stroma with thick-walled vessels.

Endometrial polyp LP mic

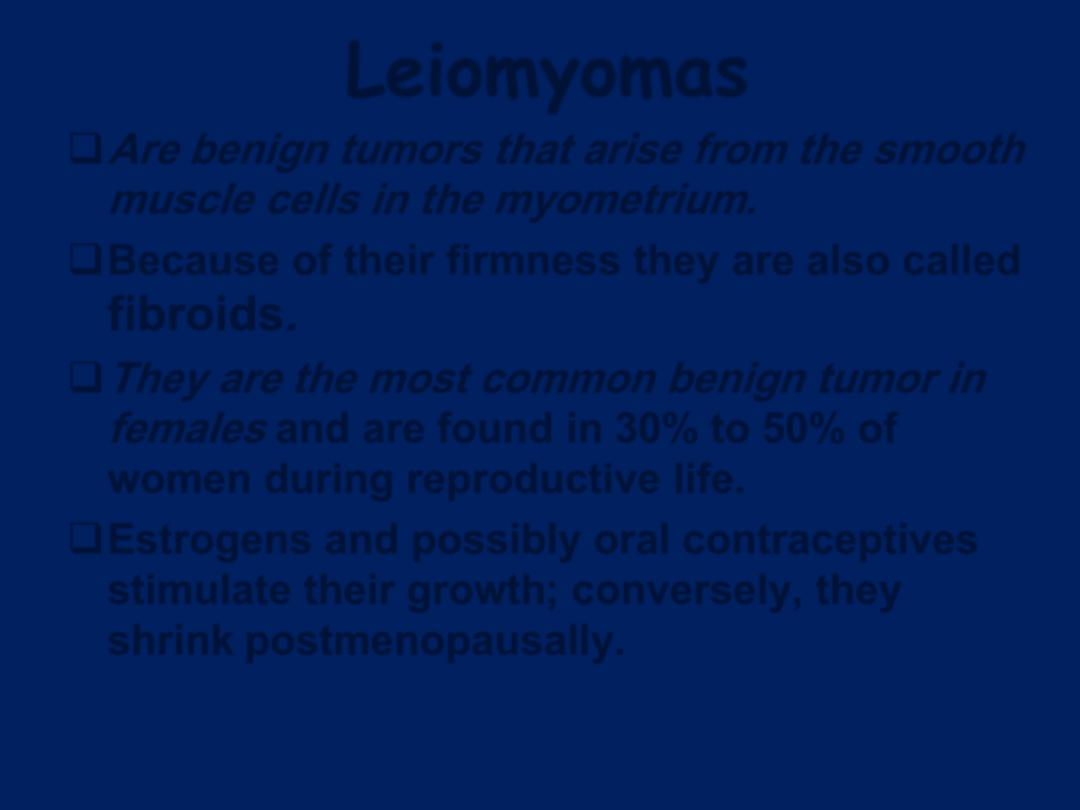

Leiomyomas

Are

benign tumors that arise from the smooth

muscle cells in the myometrium.

Because of their firmness they are also called

fibroids

.

They are

the most common benign tumor in

females

and are found in 30% to 50% of

women during reproductive life.

Estrogens and possibly oral contraceptives

stimulate their growth

; conversely, they

shrink postmenopausally.

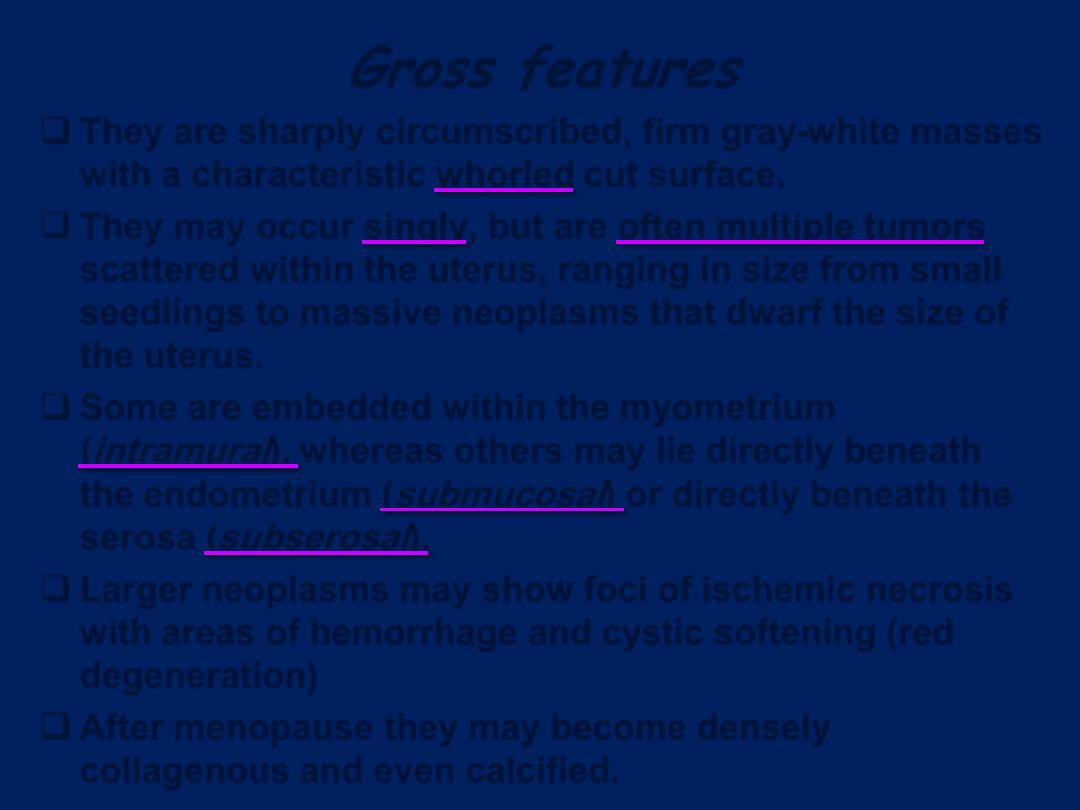

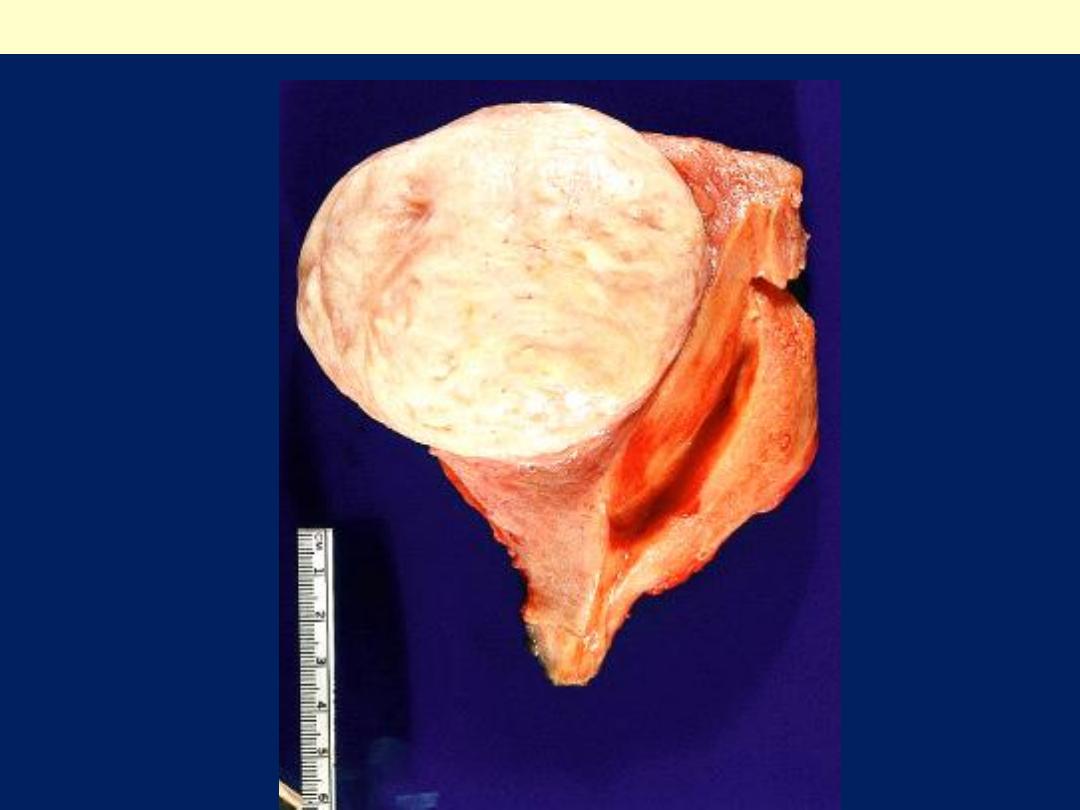

Gross features

They are sharply circumscribed, firm gray-white masses

with a characteristic

whorled

cut surface.

They may occur

singly

, but are

often multiple tumors

scattered within the uterus, ranging in size from small

seedlings to massive neoplasms that dwarf the size of

the uterus.

Some are embedded within the myometrium

(

intramural

),

whereas others may lie directly beneath

the endometrium

(

submucosal

)

or directly beneath the

serosa

(

subserosal

).

Larger neoplasms may show foci of ischemic necrosis

with areas of hemorrhage and cystic softening (red

degeneration)

After menopause they may become densely

collagenous and even calcified

.

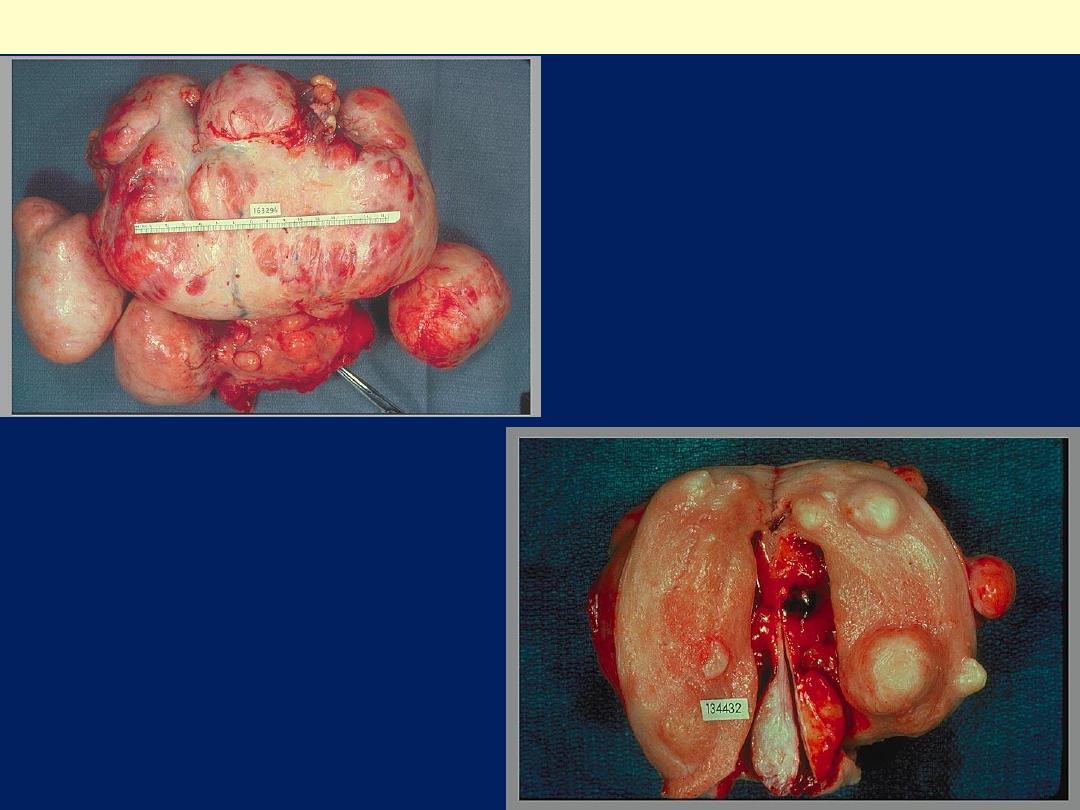

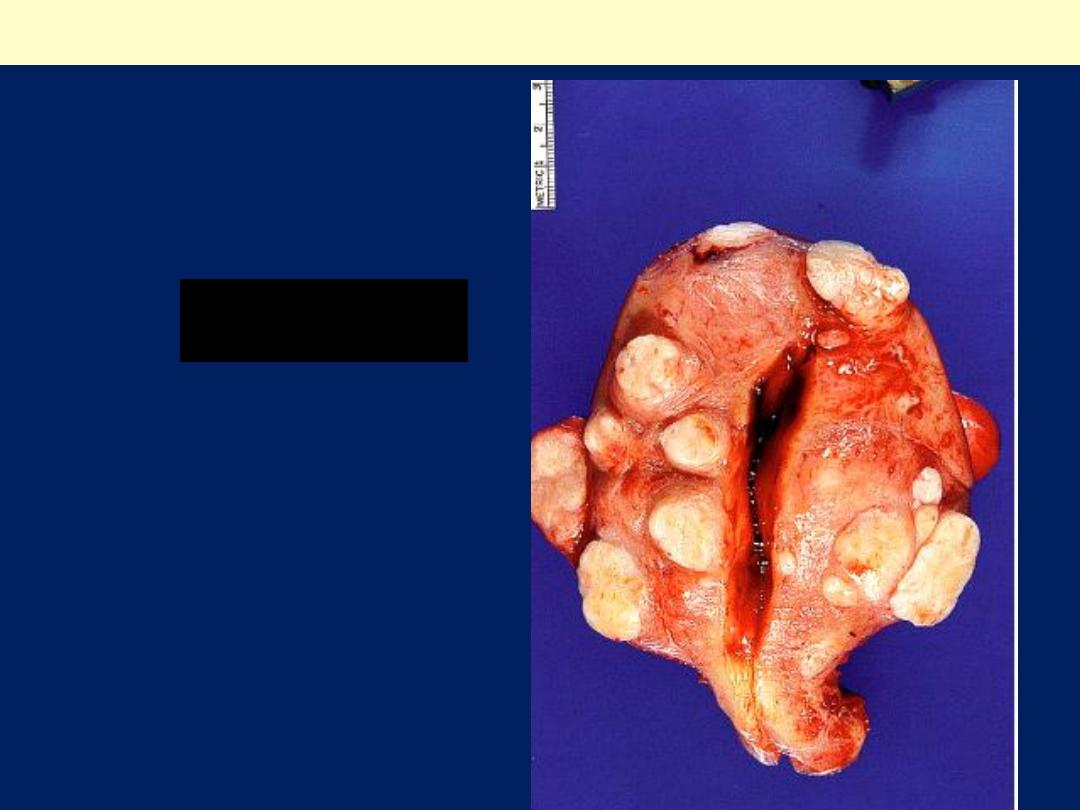

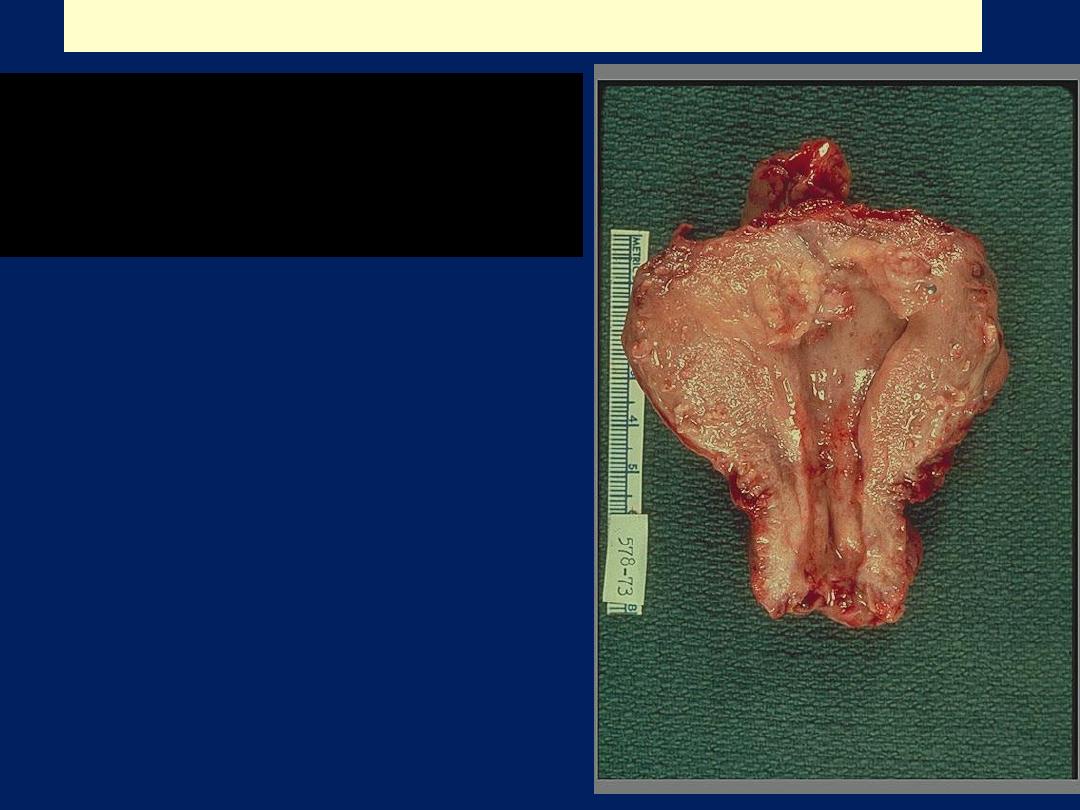

Markedly distorted

uterine corpus with

multiple irregular

masses protruding

from its surface.

These are subserosal

leiomyomata.

Leiomyomas uteri

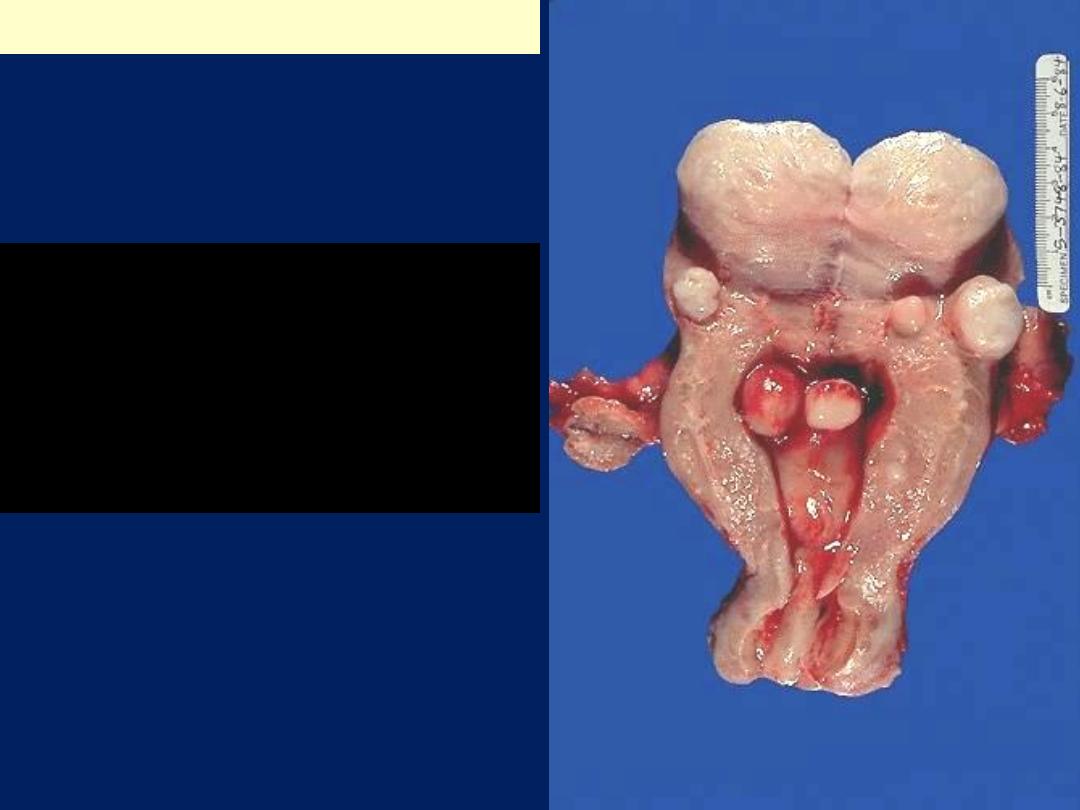

The uterus has been opened

revealing several large masses

that protrude from under the

endometrial mucosa

(submucosal). There are also

intramural and subserosal

examples. One of the

submucosal tumor is in the form

of pedunculated polyp that has

protruded through the cervix

Leiomyoma uterus gross

Multiple uterine

leiomyomas

.

Smooth muscle tumors of the

uterus are often multiple.

Seen here are submucosal,

intramural, and subserosal

leiomyomata of

the uterus.

Uterus, leiomyomata

Leiomyoma uterus gross

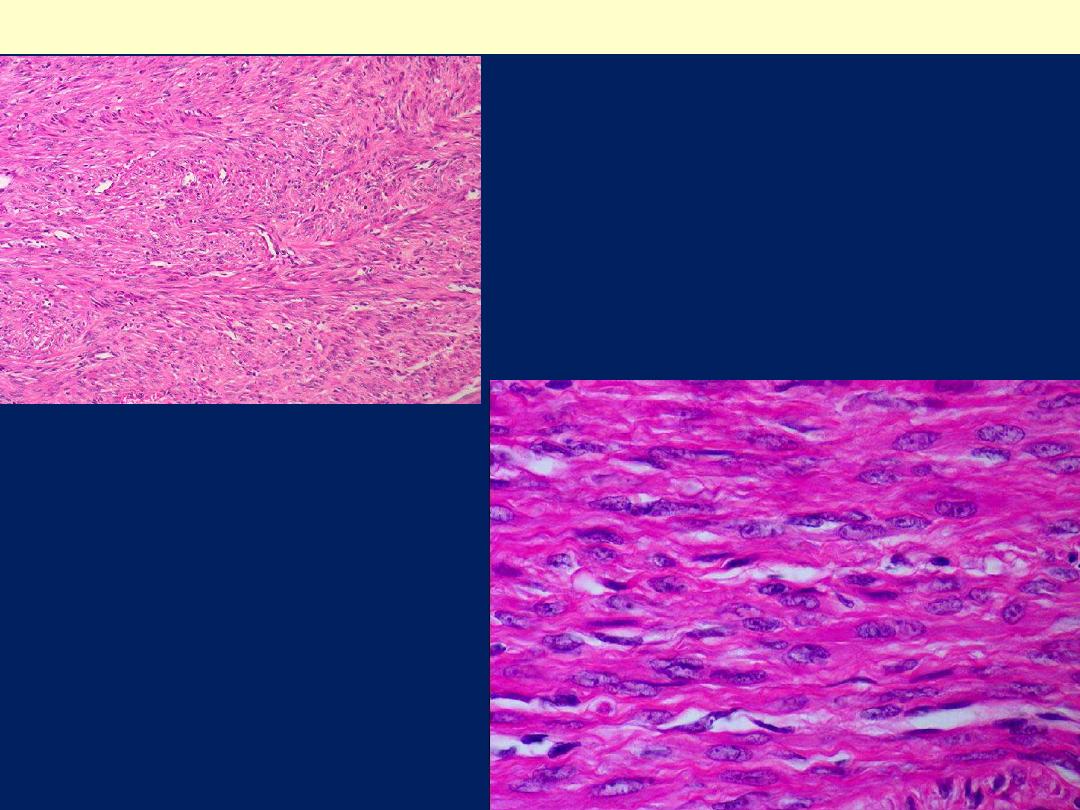

Microscopic features

There are

whorling bundles of smooth muscle cells

.

Foci of fibrosis, calcification, ischemic necrosis,

cystic degeneration, and hemorrhage may be

present.

Leiomyomas of the uterus may be entirely

asymptomatic and be discovered only on routine

pelvic examination or imaging studies.

The most frequent manifestation, when present, is

menorrhagia

.

Large masses in the pelvic region may become

palpable or may produce a

dragging sensation

.

Benign leiomyomas rarely transform into sarcomas.

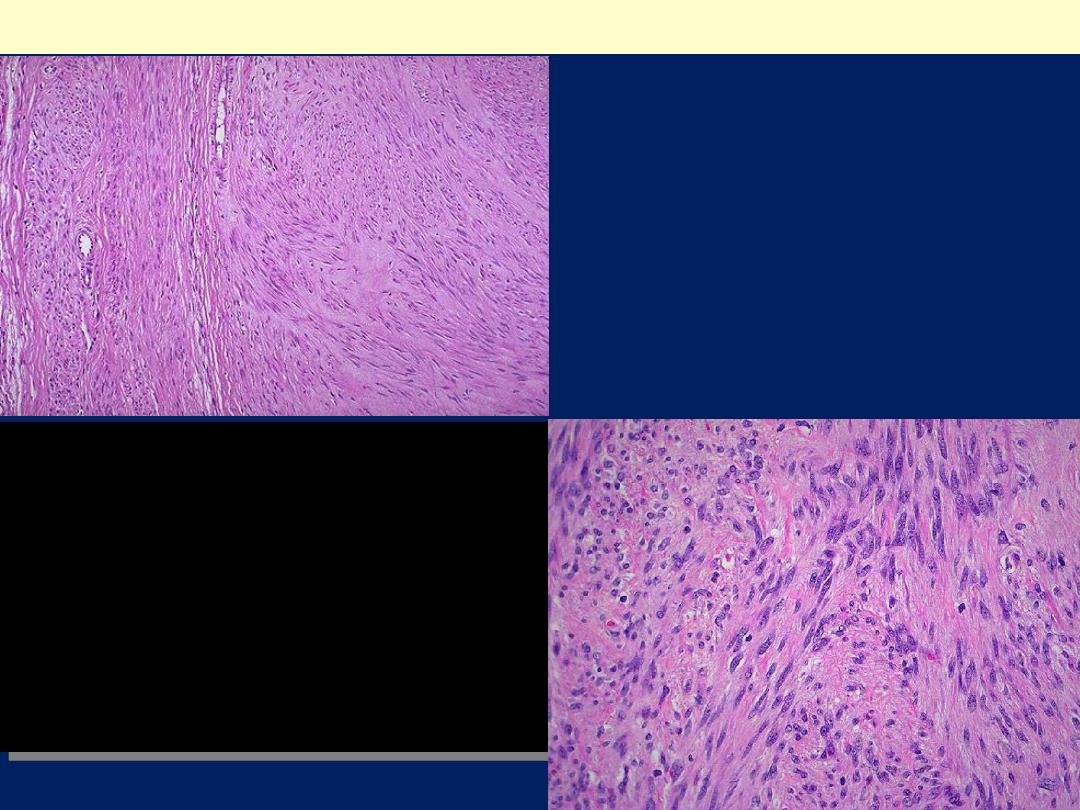

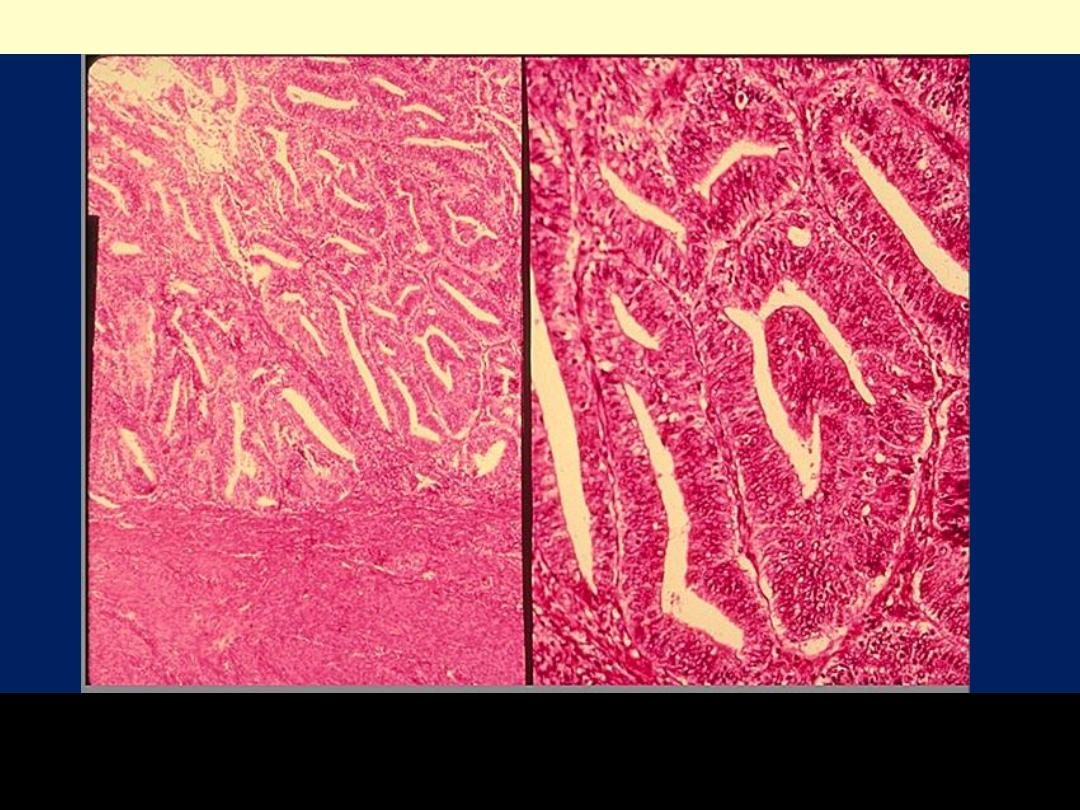

Here is the microscopic appearance

of a benign leiomyoma. Normal

myometrium is at the left, and the

neoplasm is well-differentiated so

that the leiomyoma at the right

hardly appears different. Bundles of

smooth muscle are interlacing in the

tumor mass.

Leiomyoma uteri

Leiomyoma uteri

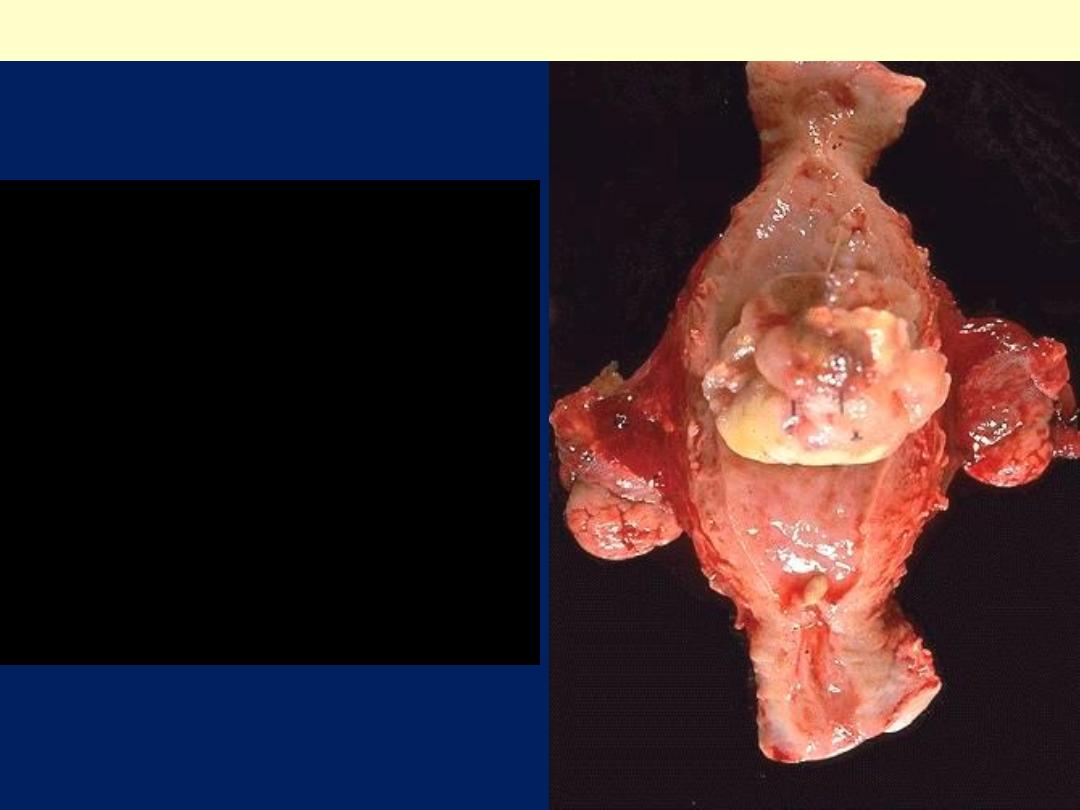

Leiomyosarcoma uterus gross

The tumor forms a large ,

irregular intramural and

submucous mass. There are

foci of hemorrhage (red) and

necrosis( yellow).

This is a leiomyosarcoma

protruding from myometrium

into the endometrial cavity of

this uterus that has been

opened sagittally so that the

halves of the cervix appear at

up and down. Fallopian tubes

and ovaries project from both

sides. The irregular nature of

this mass suggests that is not

just an ordinary leiomyoma.

Uterus, leiomyosarcoma, Gross

Leiomyosarcomas

Typically arise de novo from the

mesenchymal

cells of

the myometrium.

They are

almost always solitary tumors

, in

contradistinction to the frequently multiple leiomyomas.

Gross features

The tumor is typically bulky

It infiltrates the uterine wall.

Sometimes it projects into the endometrial cavity.

They are frequently soft, hemorrhagic, and necrotic.

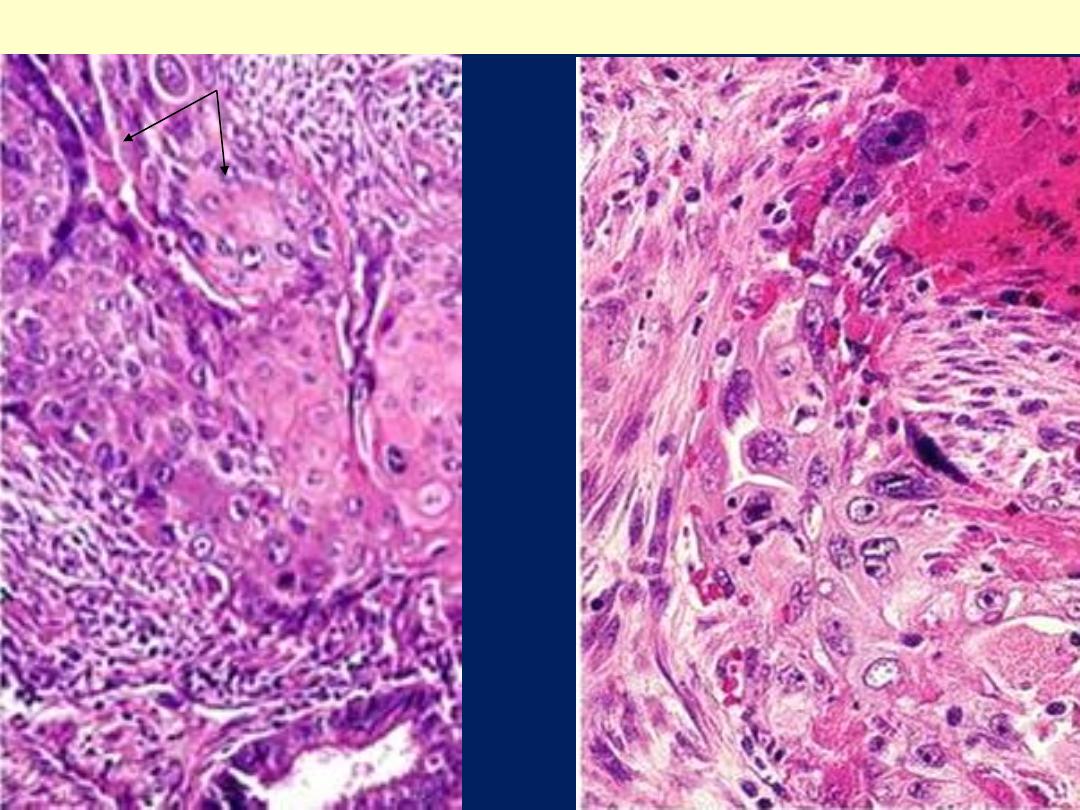

Microscopic features

They show a wide range of differentiation,

from those that closely resemble leiomyoma

to wildly anaplastic tumors.

The diagnostic features of leiomyosarcoma

include

tumor necrosis

,

cytologic atypia

, and

mitotic activity

.

Sometimes increased mitotic activity is seen

in benign smooth muscle tumors in young

women,

thus assessment of all three features

is needed to make a diagnosis of malignancy

Recurrence

after removal is common with

these cancers, and many metastasize,

typically to the lungs.

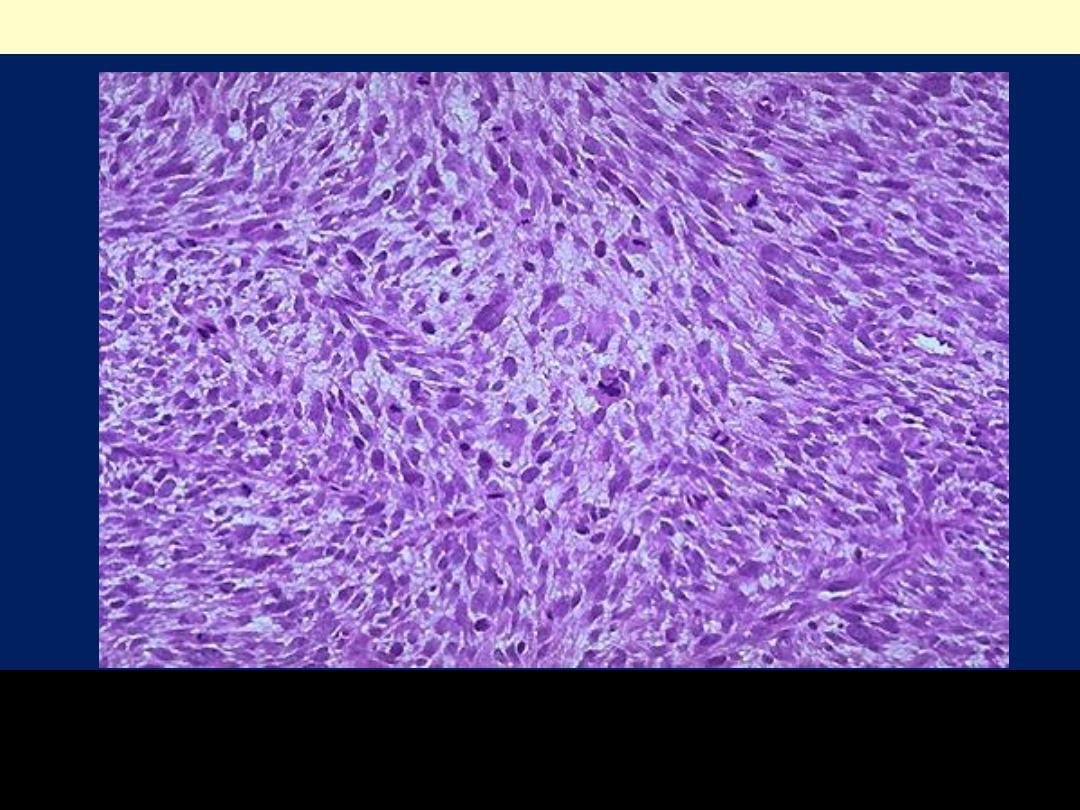

The tumor is much more cellular and the cells have much

more pleomorphism and hyperchromatism than the benign

leiomyoma. An irregular mitosis is seen in the center.

Leiomyosarcoma

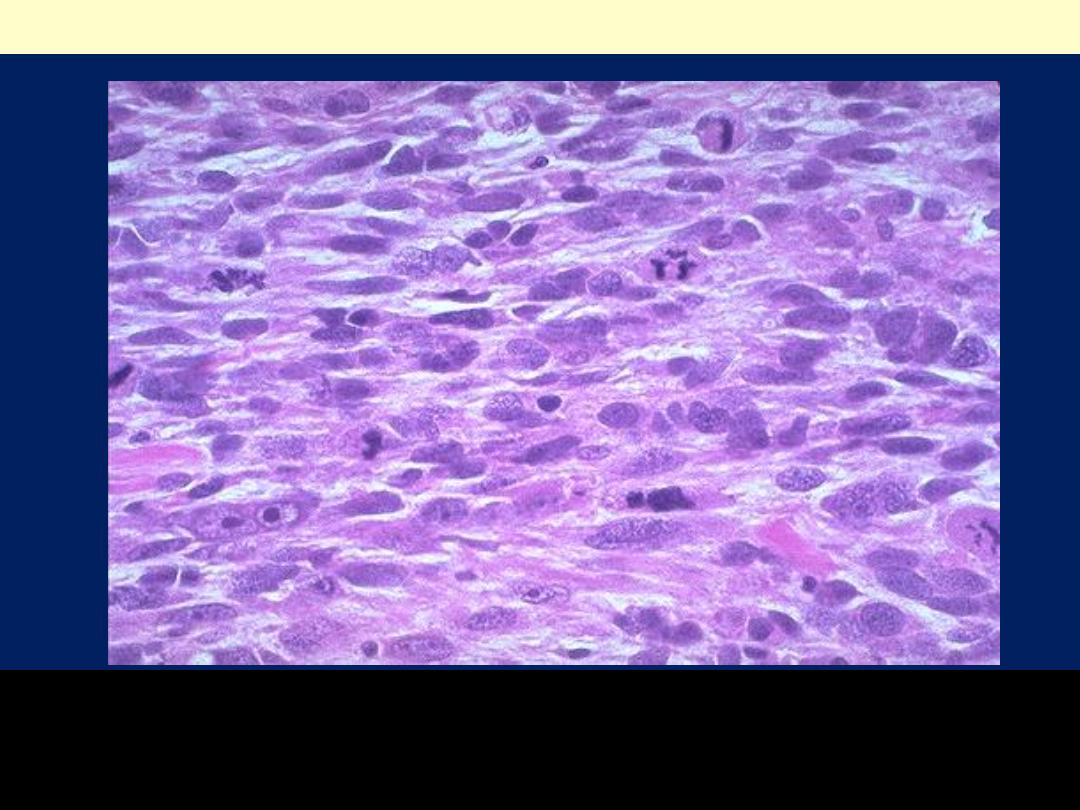

As with sarcomas in general, leiomyosarcomas have spindle

cells. Several mitoses are seen here, just in this one high

power field.

Leiomyosarcoma

Endometrial Carcinoma (EMC)

After the dramatic drop in the incidence of

cervical carcinoma, EMC is currently the most

frequent cancer occurring in the female genital

tract.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

EMC appears most frequently

around the age of

60 years.

There are

two clinico-pathological settings in

which endometrial carcinomas arise:

1. In perimenopausal women with estrogen

excess; these are of endometrioid type

2. In older women with endometrial atrophy; these

are of serous type.

Well-defined risk factors for endometrioid

carcinoma include

a.

Obesity: associated with increased synthesis of

estrogens in fat depots

b. Diabetes

c. Hypertension

d. Infertility: women tend to be nulliparous, often

with anovulatory cycles.

e-prolonged estrogen replacement therapy and

estrogen-secreting ovarian tumors increase the

risk of this form of cancer.

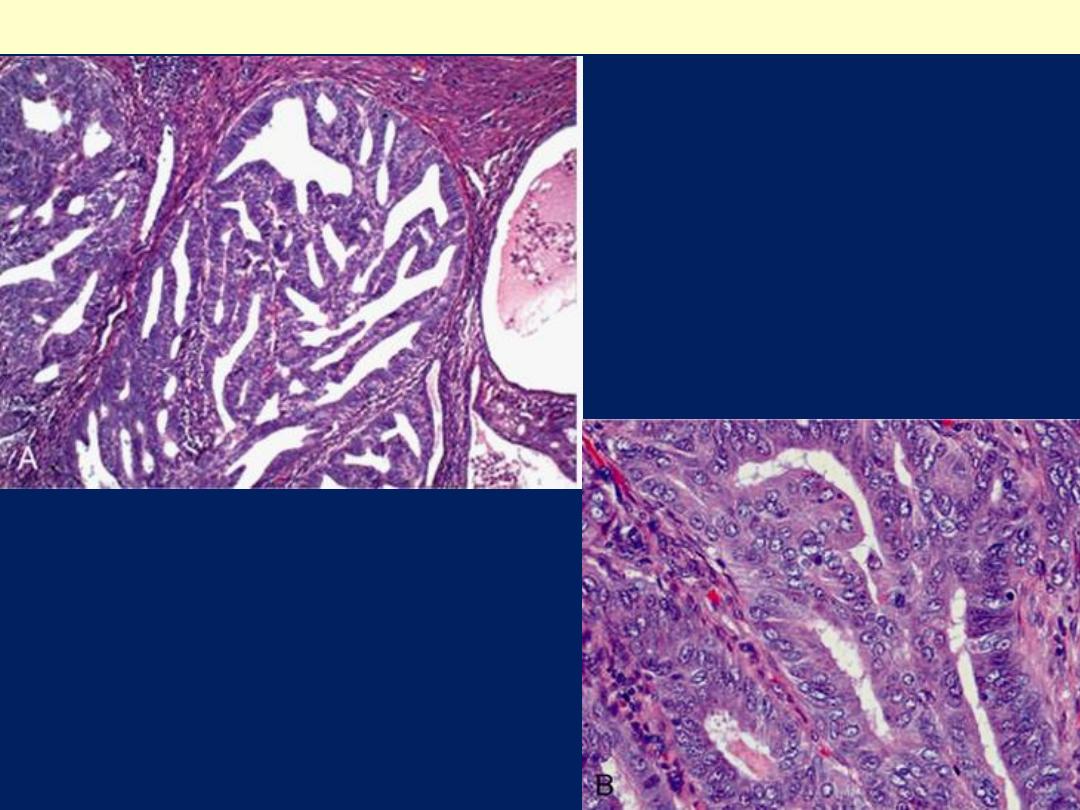

The tumor shown is

polypoid (exophytic)

Endometrial adenocarcinoma

The tumor shown is

extensive, nodular & highly

infiltrating.

Endometrial adenocarcinoma

A mass with foci of hemorrhage

within the uterine corpus

consistent with a fungating

endometrial adenocarcinoma

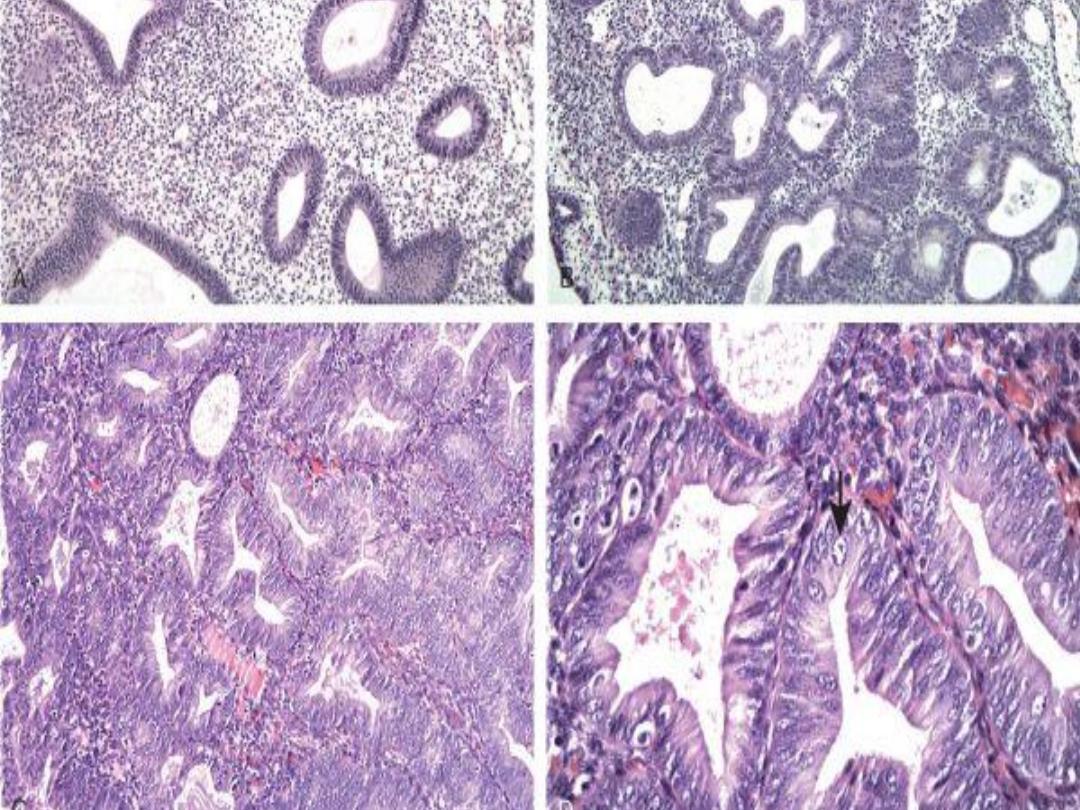

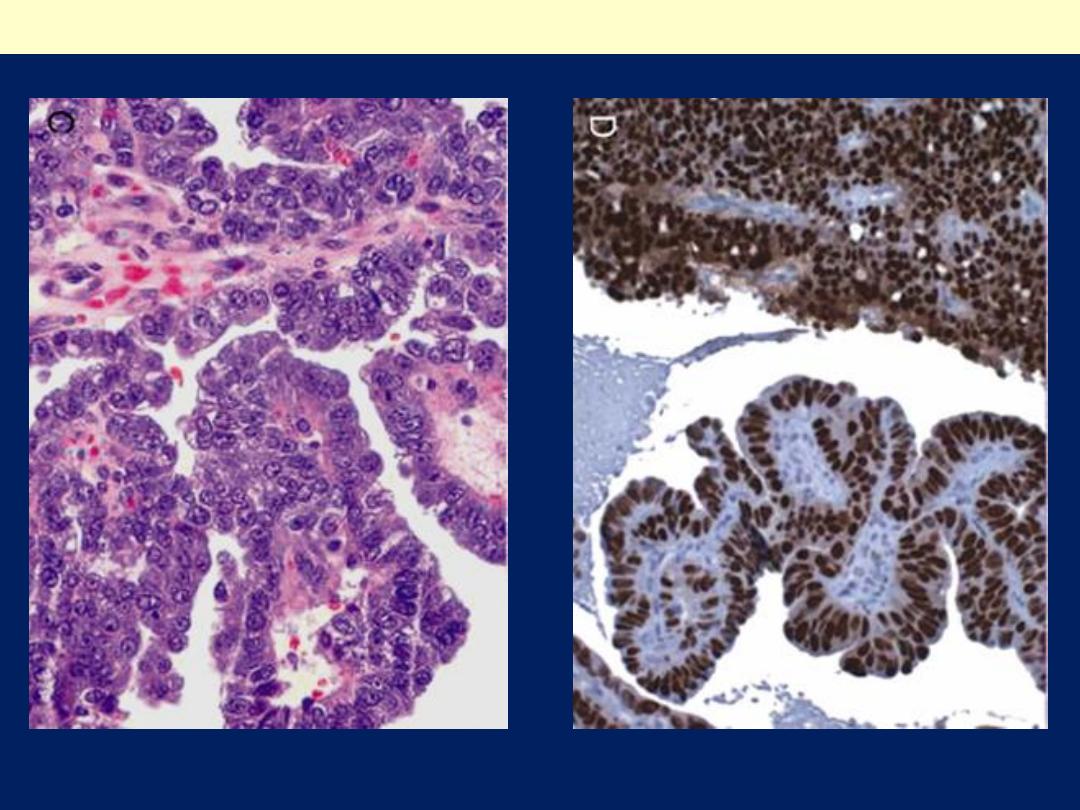

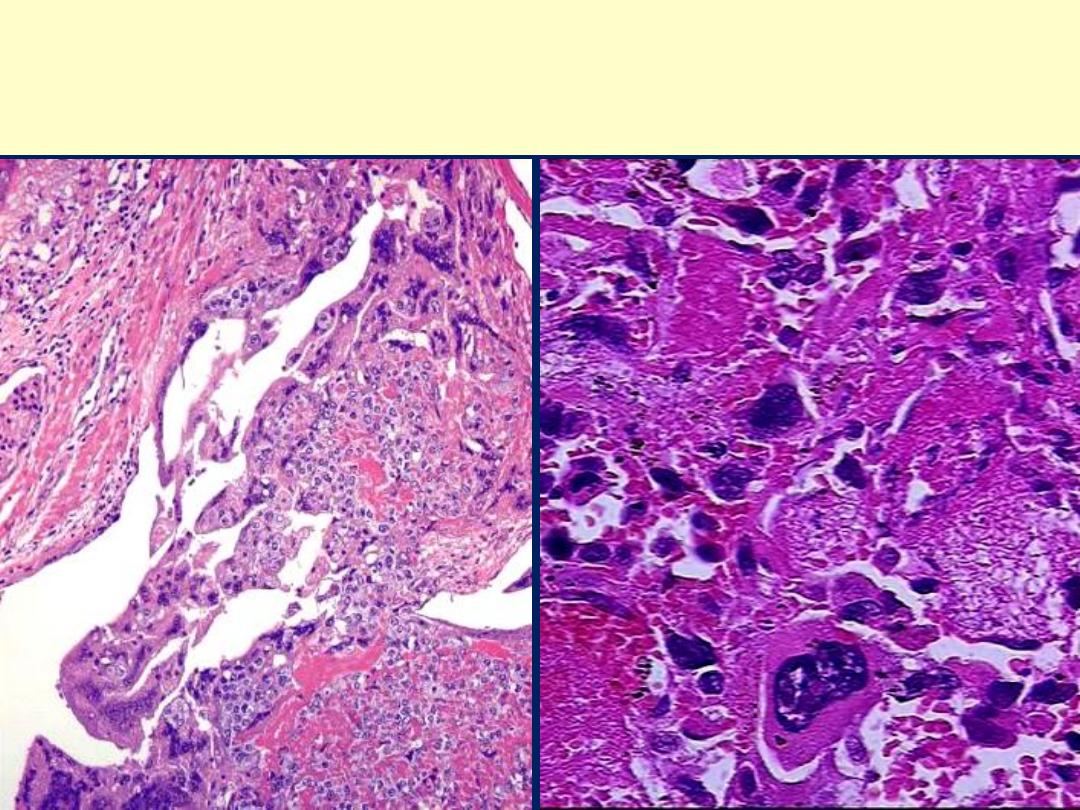

A, Endometrioid type,

infiltrating myometrium

and displaying cribriform

architecture. B, Higher

magnification reveals loss

of polarity and nuclear

atypia.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

The endometrial glands are crowded, in a back-to-back arrangement;

these glands are very complex with a gland within gland pattern. The

lining consists of cells with pseudostratification and disorganization

Endometrioid carcinoma

Moderately-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Poorly-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Adenosquamous carcinoma

C, displaying formation of papillae and marked cytologic atypia. D, Immunohistochemical

stain for p53 reveals accumulation of mutant p53 in serous carcinoma.

Serous carcinoma of the endometrium

Pyosalpinx

Outer aspect of pyosalpinx.

Cut surface of pyosalpinx; the tube

is distended with yellow pus

Tubo-ovarian abscess

Fusion of fallopian tube and ovary into a tubo-ovarian abscess.

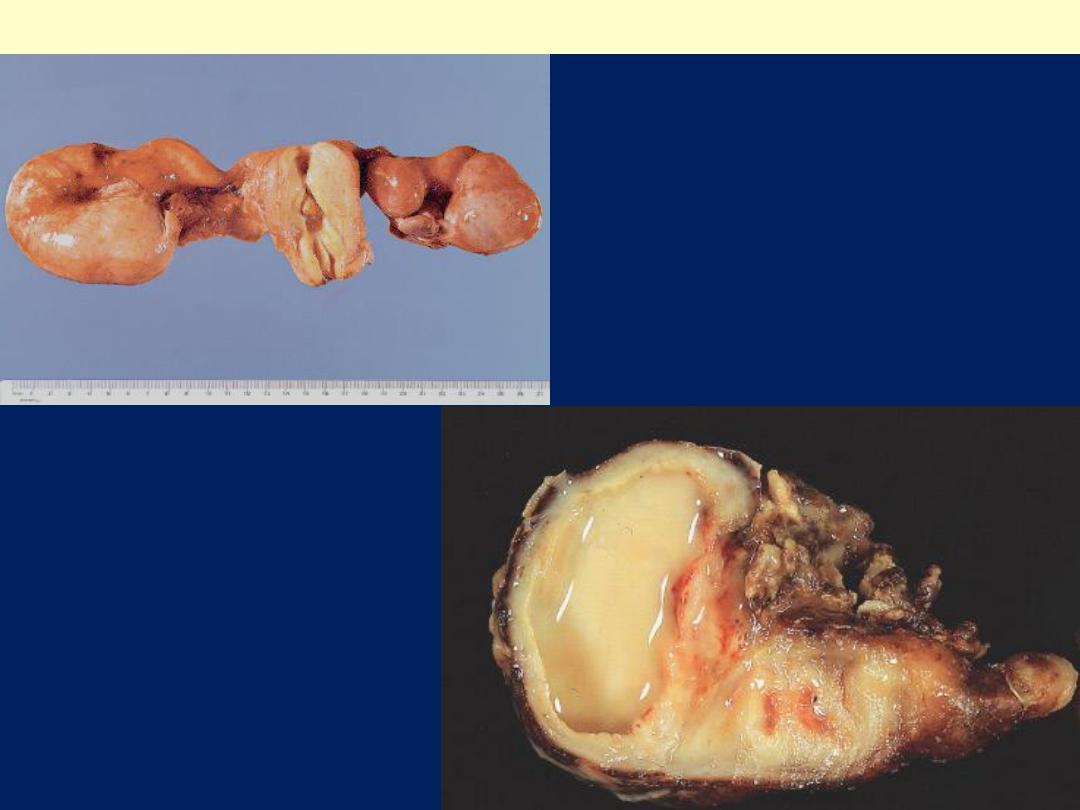

Hematosalpinx: tubal gestation

Ruptured tubal pregnancy

with marked hemorrhage

(hematosalpinx). The tiny

embryo is identifiable in

the center of the clot.

This is a ruptured tubal ectopic

pregnancy. Note the twin

fetuses at the lower right

adjacent to the blood clot at the

left

*

.

A positive pregnancy test (presence of human chorionic

gonadotropin), ultrasound, and culdocentesis with presence

of blood are helpful in making the diagnosis of ectopic

pregnancy. Note the presence of chorionic villi &

hemorrhage within the tubal lumen

Tubal pregnancy

Gestational Trophoblastic Tumors

These are divided into four morphologic

categories:

1. Hydatidiform mole

a. Complete

b. Incomplete

2. Invasive mole

3. Choriocarcinoma.

4. Placental site trophoblastic tumor

All the three produce

human chorionic gonadotropin

(hCG),

which can be detected in the circulating blood and

urine, at much higher titers .

The titers are progressively rising from hydatidiform mole

to invasive mole to choriocarcinoma.

In addition to aiding diagnosis, the fall or rise in the level of

the hormone in the blood or urine can be used to monitor

the effectiveness of treatment.

1. Hydatidiform Mole:

•

Complete and Partial

•

The typical hydatidiform mole is a large mass of

hydropic swollen chorionic villi, appearing

grossly as grapelike structures.

A. The complete hydatidiform mole

does not

permit embryogenesis and thus does not

contain fetal parts.

and the chorionic epithelial cells are diploid (46,

XX or, uncommonly, 46, XY).

B. The partial hydatidiform mole

permits early embryogenesis , has some

normal chorionic villi, and is almost always

triploid (e.g., 69, XXY).

The two patterns result from

abnormal

fertilization

;.

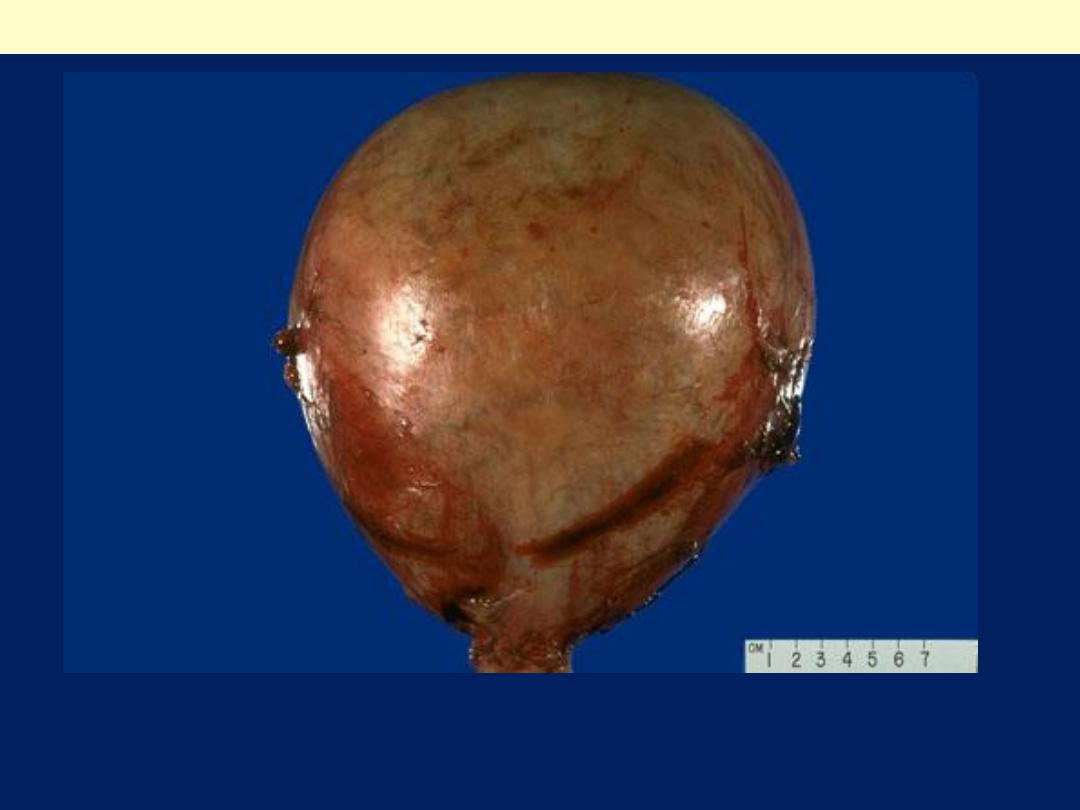

This is only a second trimester pregnancy, but note how large for dates

the uterus is because of a molar pregnancy. An ultrasound in this case

revealed no fetus, only a "snowstorm" effect.

Complete hydatidiform mole

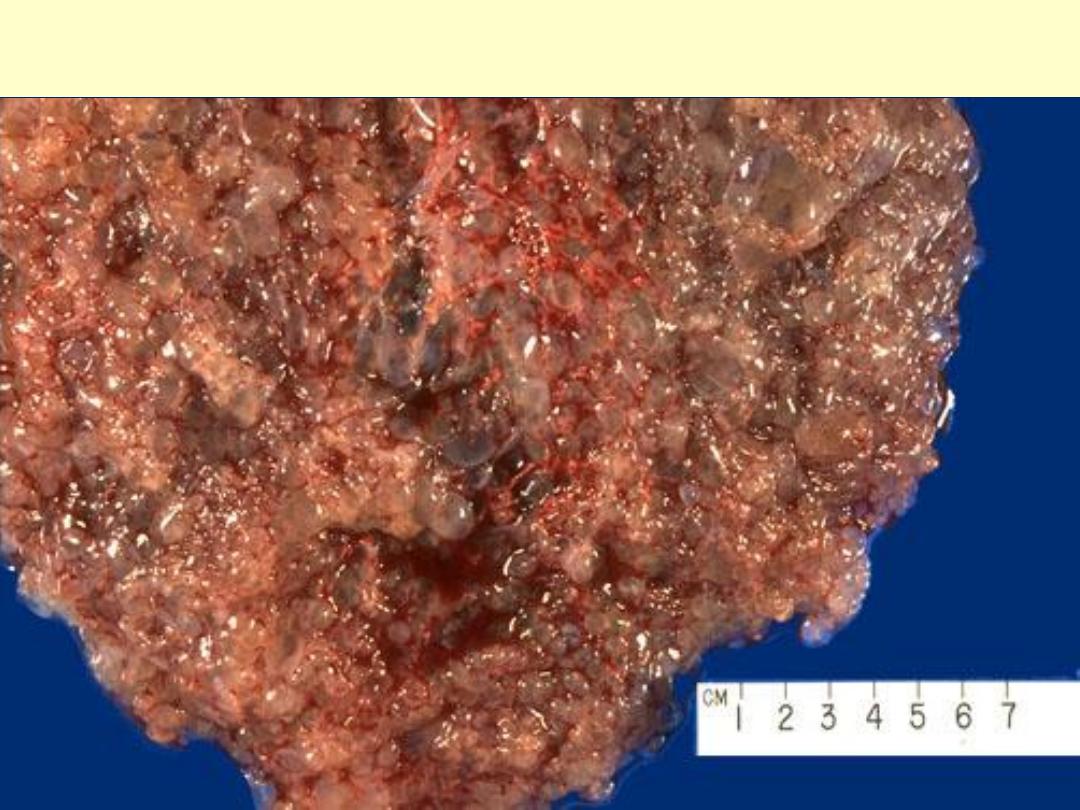

Complete hydatidiform mole:A mass of tissue with grape-like

swollen villi.

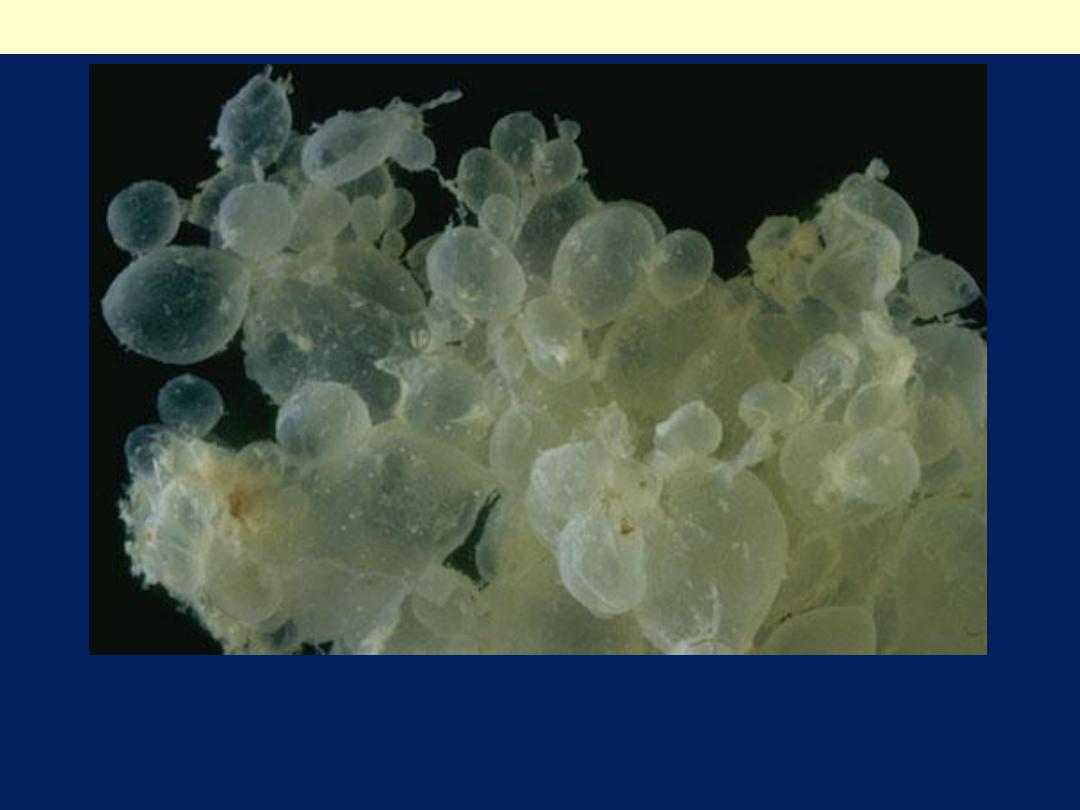

The grape-like villi of a hydatidiform mole are seen here suspended in saline. With molar

pregnancy, the uterus is large for dates, but no fetus is present. HCG levels are markedly

elevated. Patients with a hydatidiform mole are often large for dates and have hyperemesis

gravidarum more frequently. Patients may present with bleeding, and may pass some of the

grape-like villi.

Complete hydatidiform mole

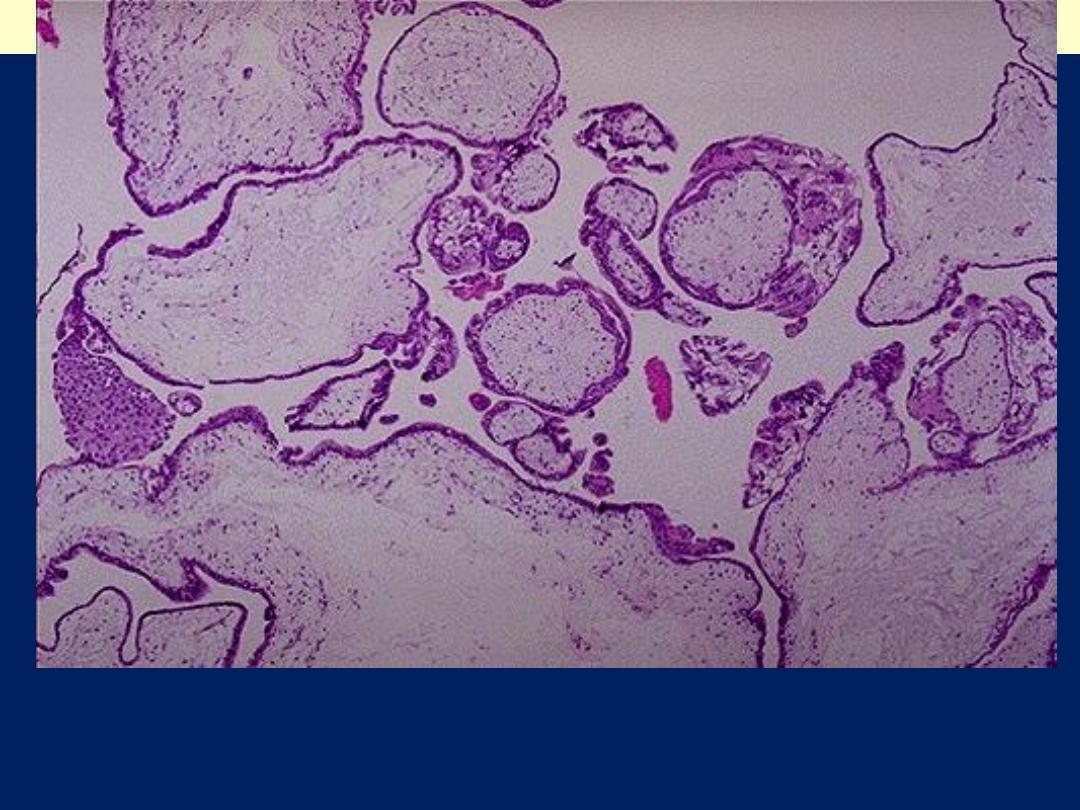

Complete H. mole: Note the large avascular villi and areas of

trophoblastic proliferation. An ultrasound confirms the diagnosis before

currettage is done to evacuate the molar tissue seen here.

Complete hydatidiform mole

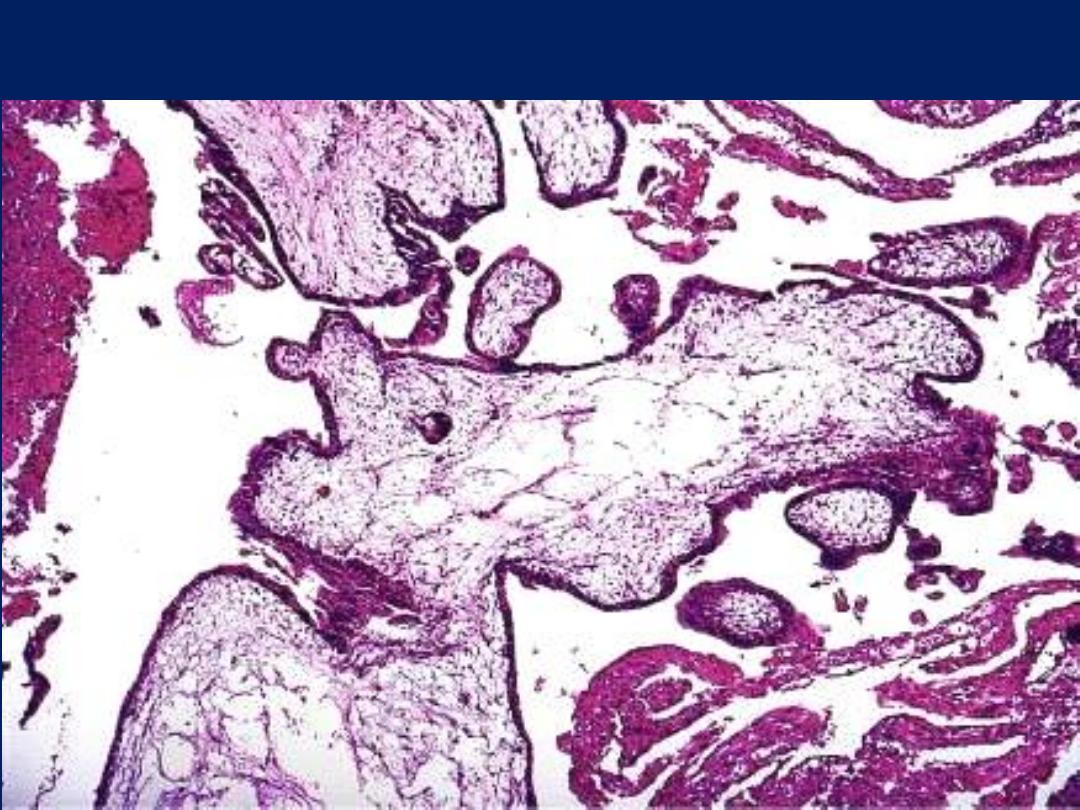

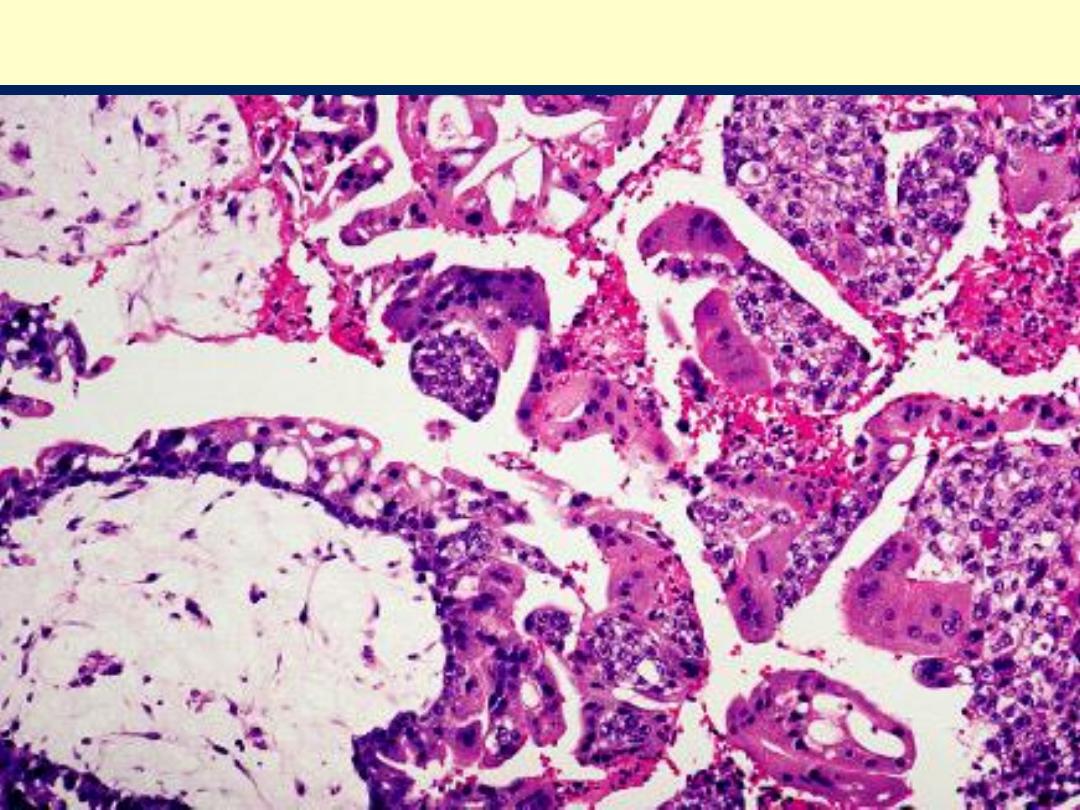

Partial mole showing scalloping of villi and isolated trophoblastic cells

embedded in the stroma.

Complete H. mole showing large villi with stromal edema and

marked trophoblastic proliferation.

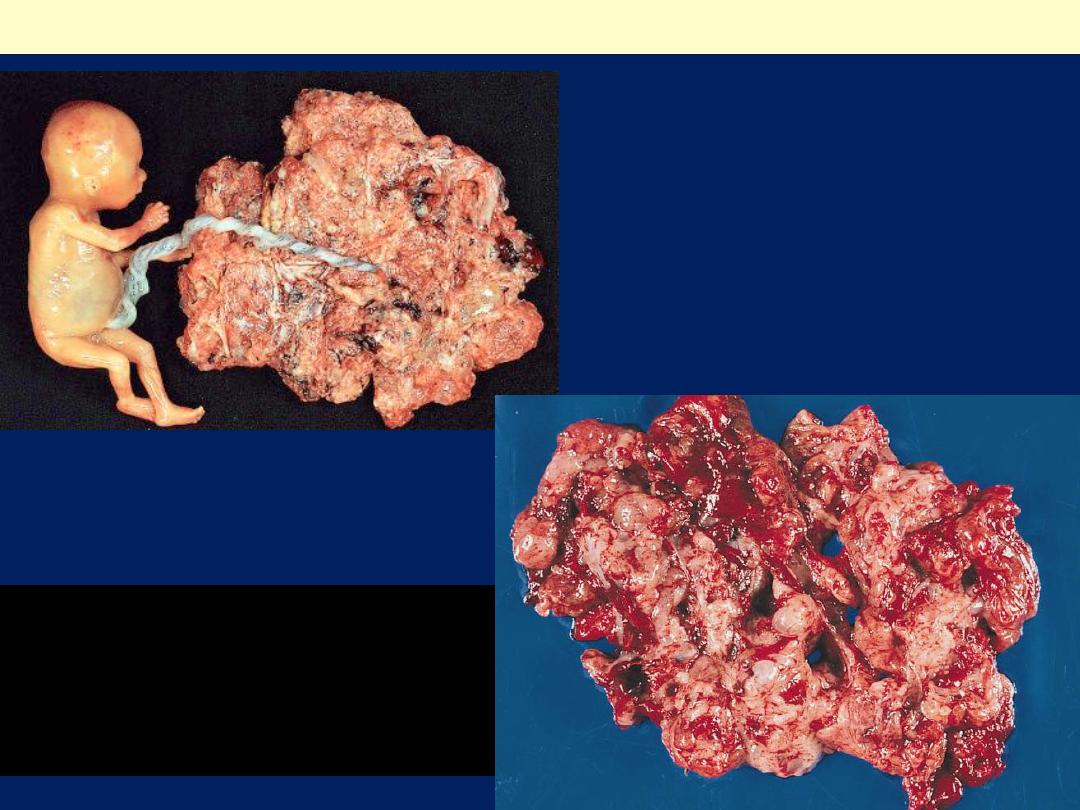

Partial mole with attached fetus.

The diagnosis was confirmed by

biopsy and flow cytometry. The

fetus showed no abnormality and

was connected to the mole by a

normal umbilical cord.

Partial Hydatidiform mole

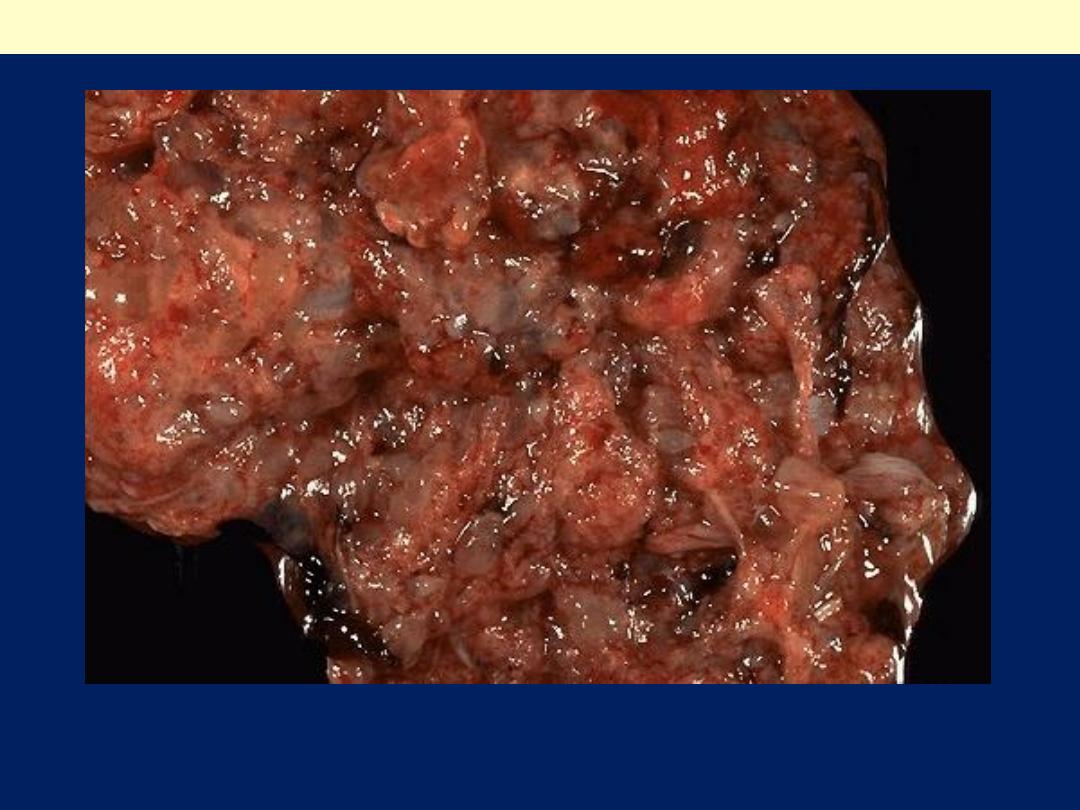

Gross appearance of partial

mole. The hydropic degeneration

of the villi is not as pronounced

as in the classical complete

mole.

Partial moles

The villous edematous swelling involves only some

of the villi and the trophoblastic proliferation is

focal and slight.

The villi of partial moles have a characteristic

irregular scalloped margin.

There may be fetal red blood cells in placental villi

or, in some cases, a fully formed fetus that,

despite a triploid karyotype, is morphologically

nearly normal in appearance.

This is a partial mole that occurs when two sperms fertilize a single ovum. The result is

triploidy (69 XXY). Only some of the villi are grape- like, and a fetus can be present, but

rarely survives past 15 weeks.

Partial hydatidiform mole

In partial moles, some villi (as seen here at the lower left) appear normal,

whereas others are swollen. There is minimal trophoblastic proliferation.

Partial hydatidiform mole

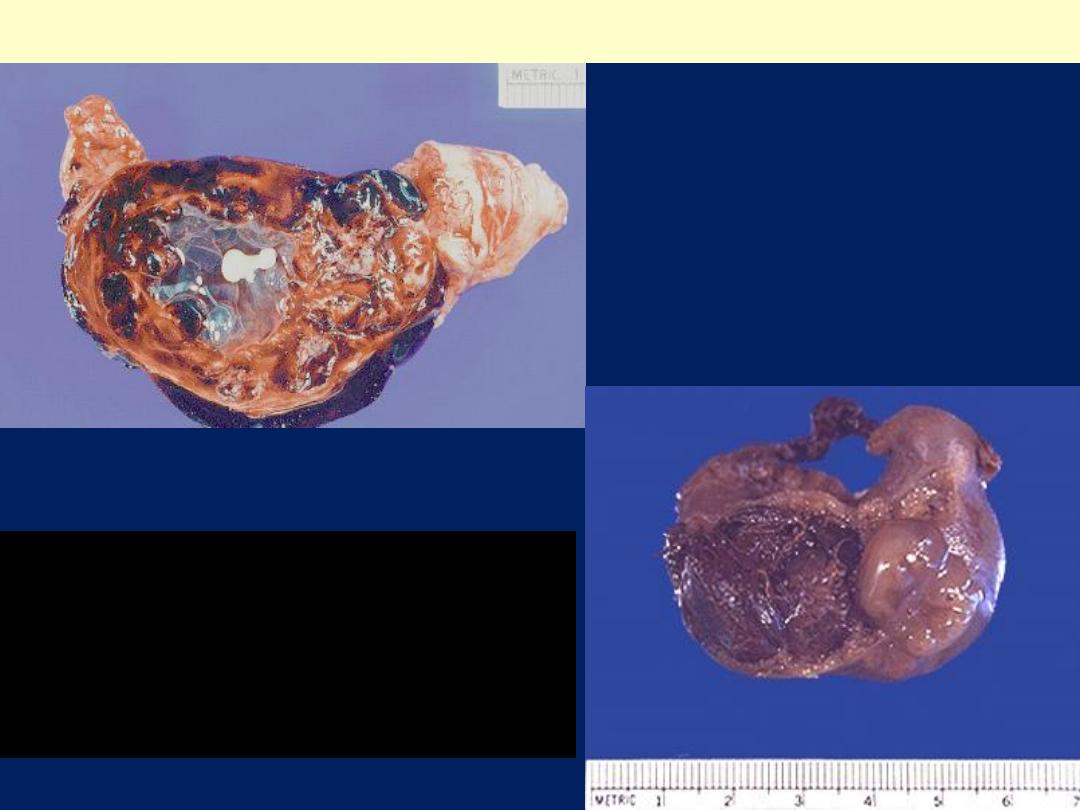

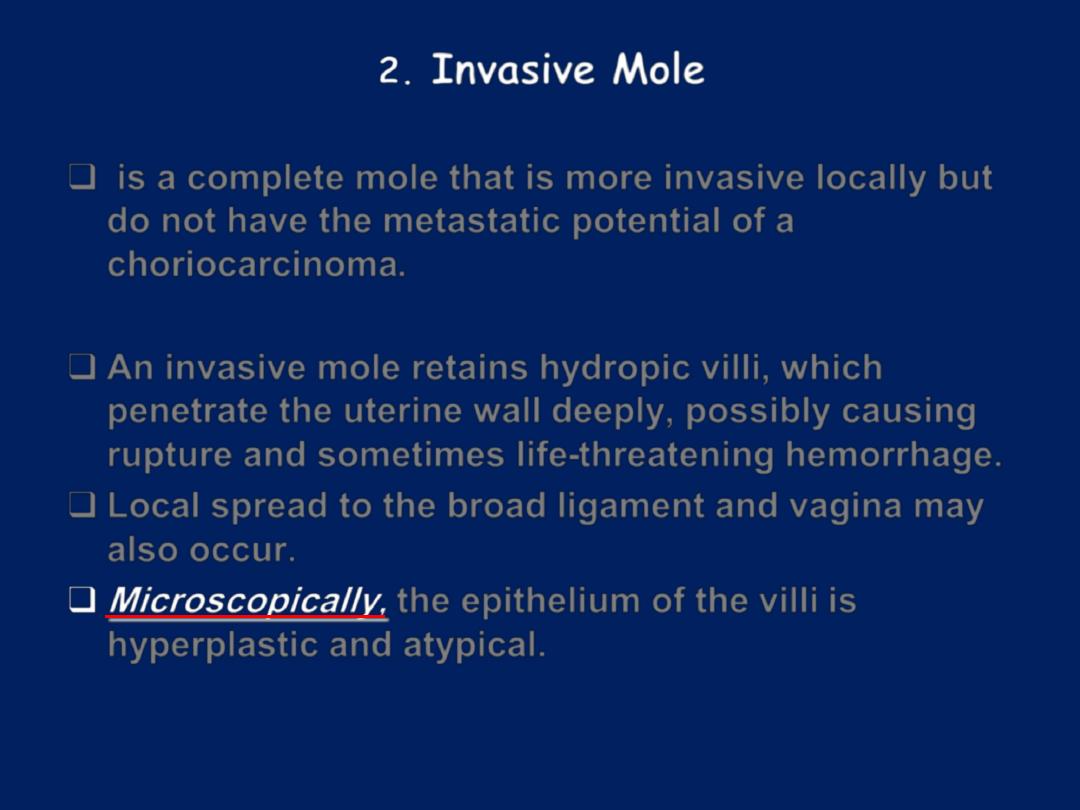

2.

Invasive Mole

is a complete mole that is more invasive locally but

do not have the metastatic potential of a

choriocarcinoma.

An invasive mole retains hydropic villi, which

penetrate the uterine wall deeply, possibly causing

rupture and sometimes life-threatening hemorrhage.

Local spread to the broad ligament and vagina may

also occur.

Microscopically,

the epithelium of the villi is

hyperplastic and atypical.

Invasive mole

.

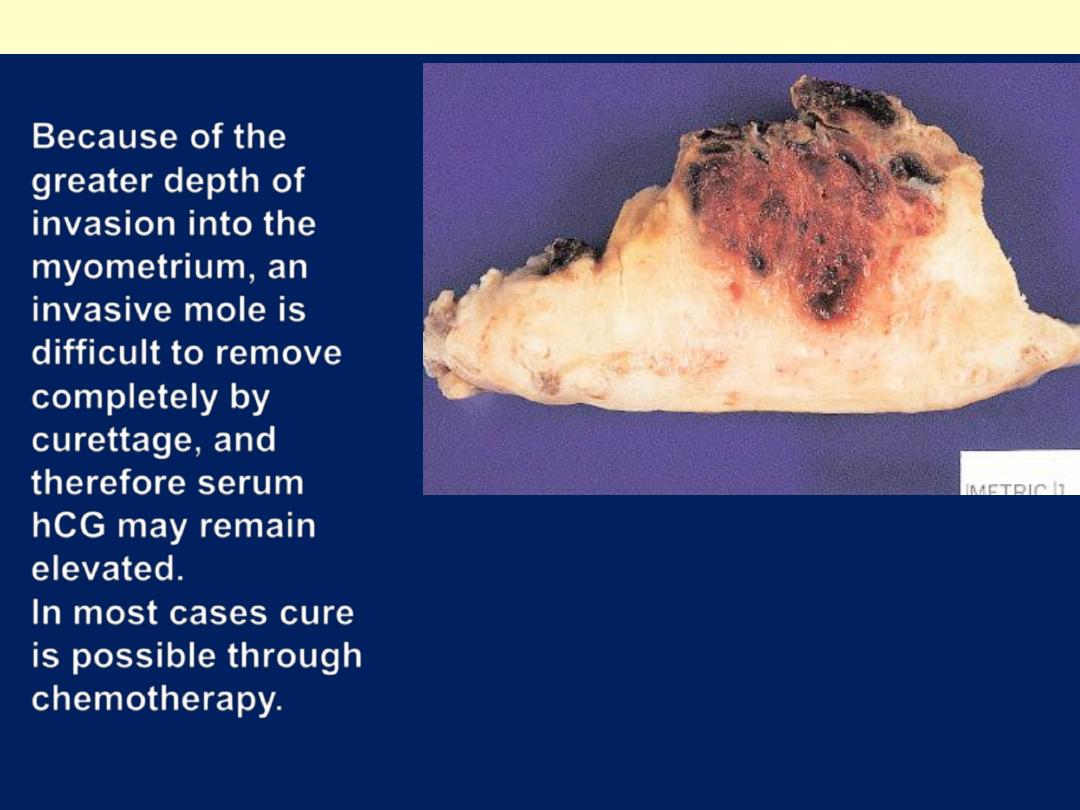

Because of the

greater depth of

invasion into the

myometrium, an

invasive mole is

difficult to remove

completely by

curettage, and

therefore serum

hCG may remain

elevated.

In most cases cure

is possible through

chemotherapy.

Gross appearance

of invasive mole

A hemorrhagic mass

has permeated

half of the thickness

of the myometrial wall

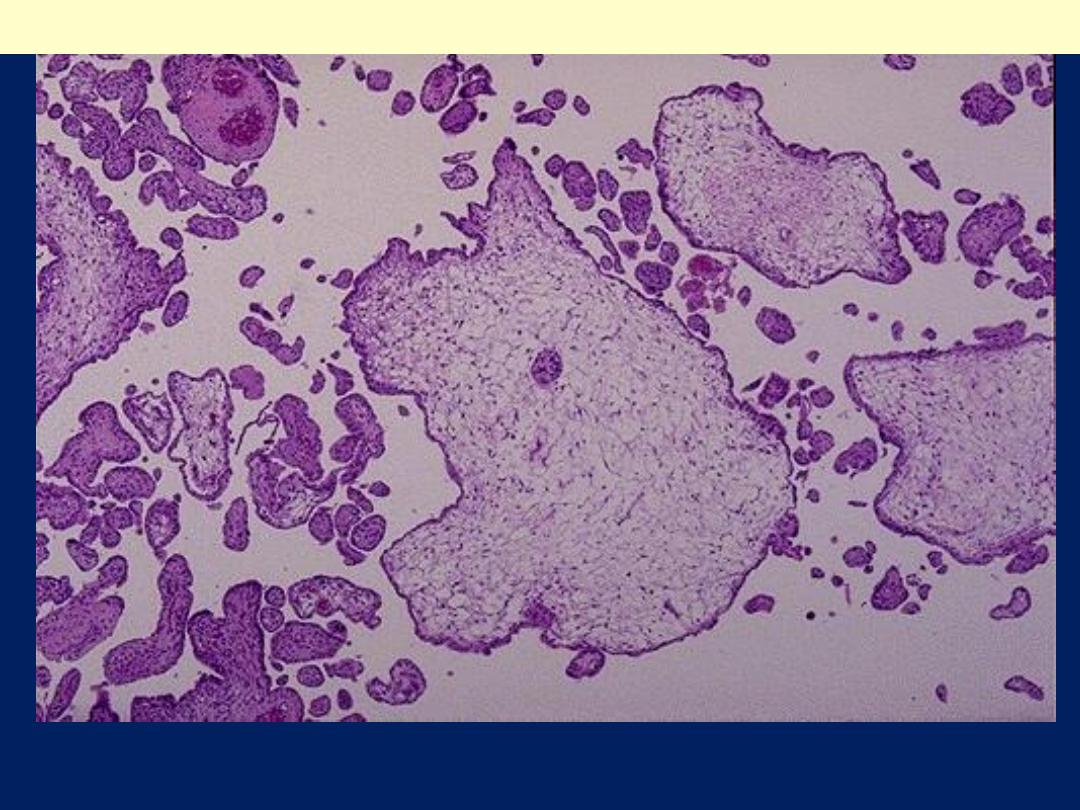

Innasive mole: Hydropic villi covered by proliferating trophoblast are

seen permeating the myometrium in this invasive mole.

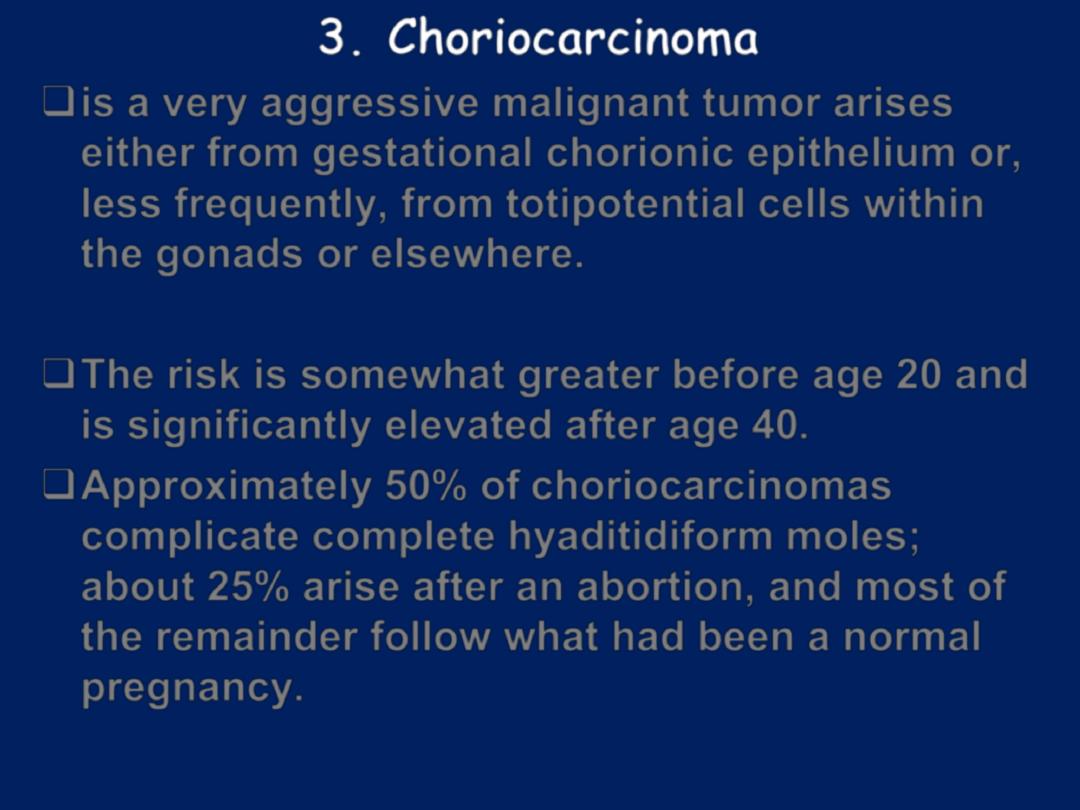

3. Choriocarcinoma

is a very aggressive malignant tumor arises

either from gestational chorionic epithelium or,

less frequently, from totipotential cells within

the gonads or elsewhere.

The risk is somewhat greater before age 20 and

is significantly elevated after age 40.

Approximately 50% of choriocarcinomas

complicate complete hyaditidiform moles;

about 25% arise after an abortion, and most of

the remainder follow what had been a normal

pregnancy.

Most cases are discovered by the

appearance of a bloody or brownish

discharge accompanied by a rising titer of

hCG, particularly the β-subunit, in blood and

urine, and the absence of marked uterine

enlargement, such as would be anticipated

with a mole.

In general, the titers are much higher than

those associated with a mole.

Choriocarcinoma- uterus

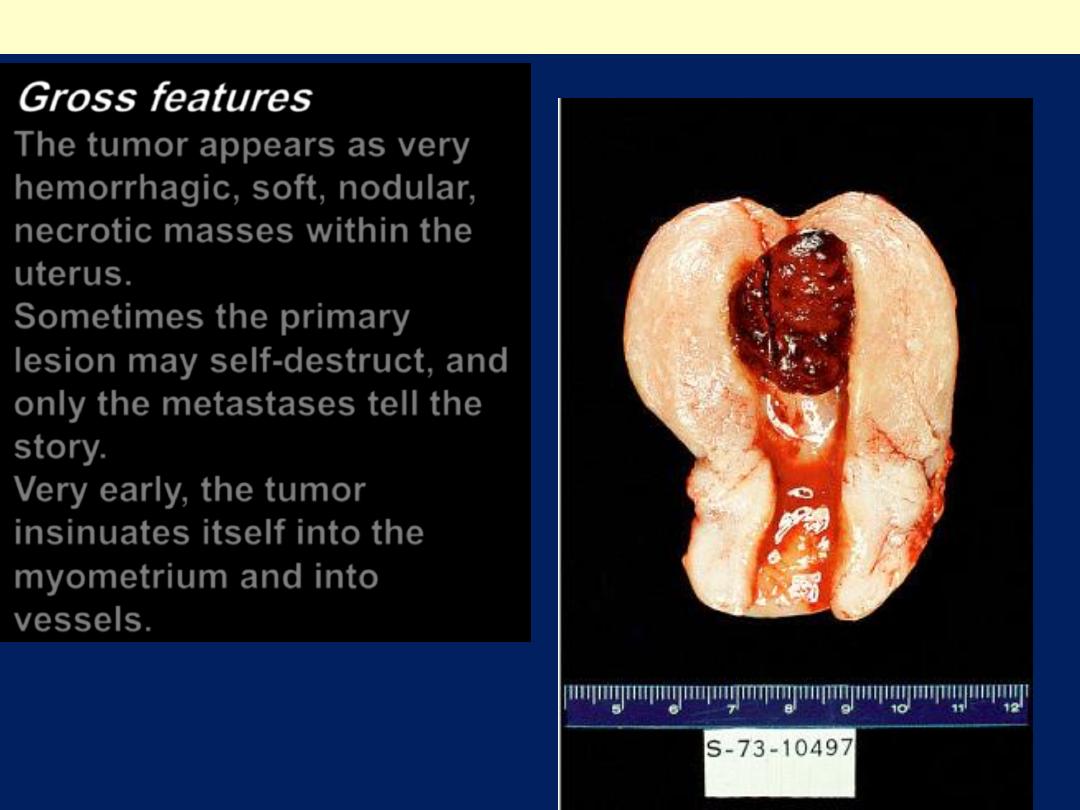

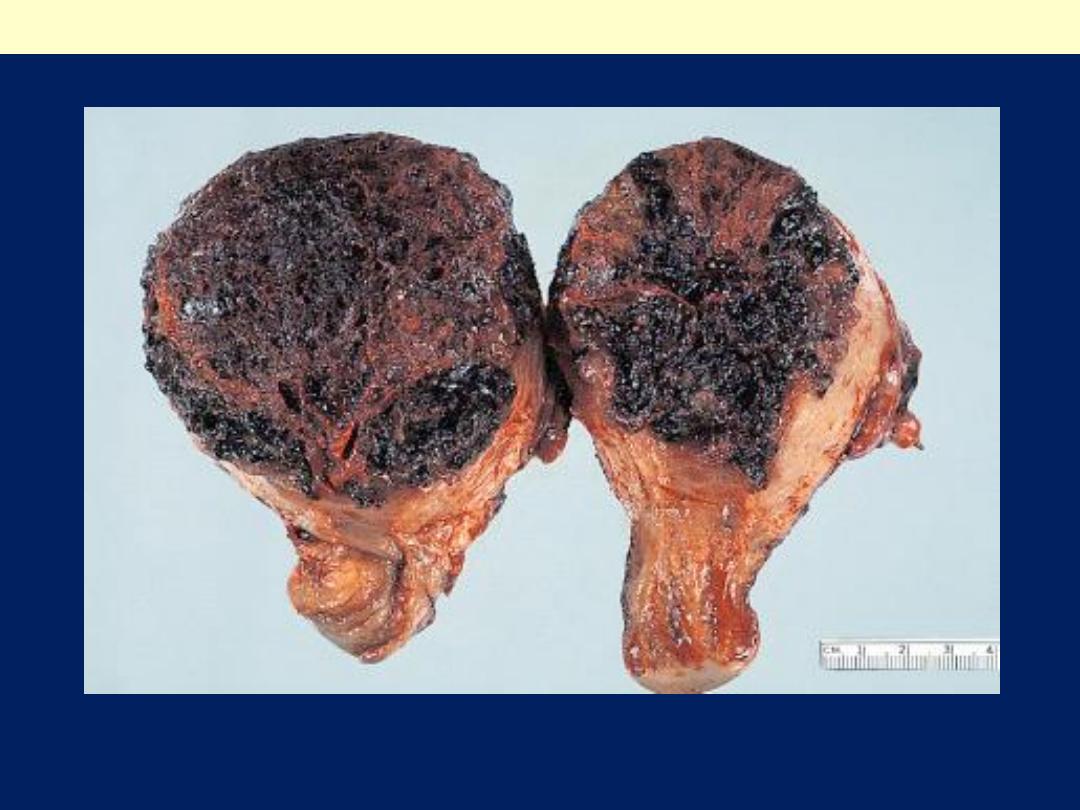

Gross features

The tumor appears as very

hemorrhagic, soft, nodular,

necrotic masses within the

uterus.

Sometimes the primary

lesion may self-destruct, and

only the metastases tell the

story.

Very early, the tumor

insinuates itself into the

myometrium and into

vessels.

Uterine choriocarcinoma showing typical highly hemorrhagic appearance.

Choriocarcinoma uterus

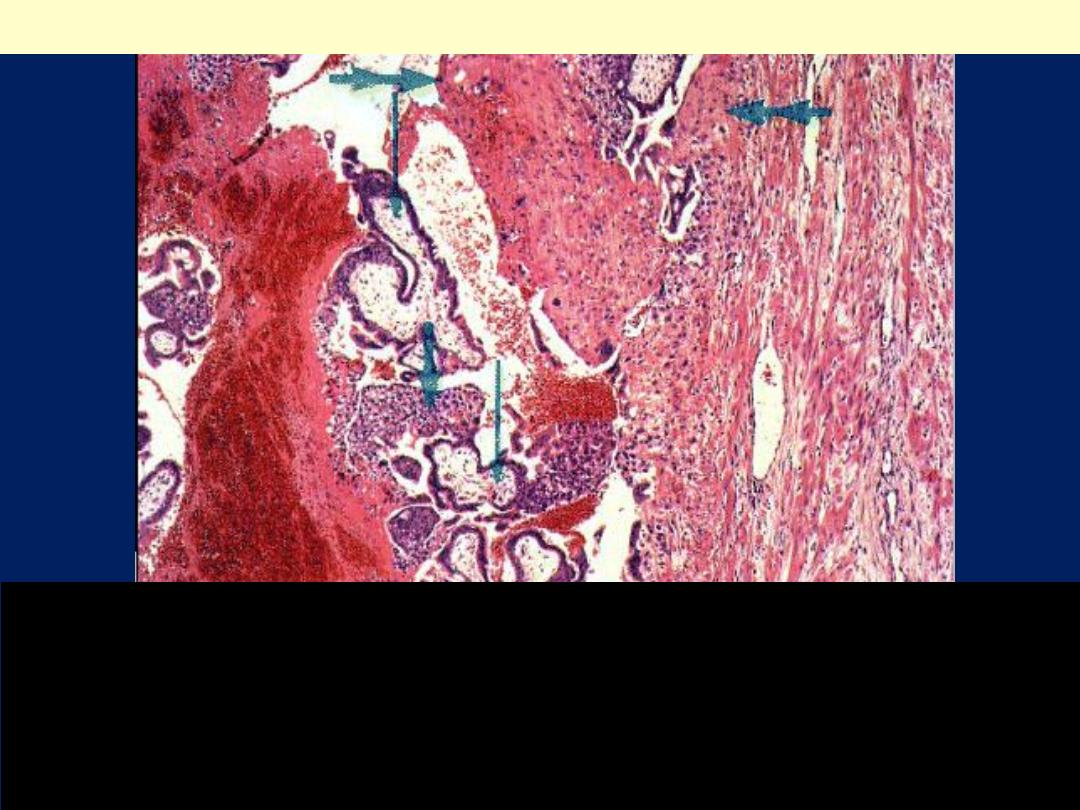

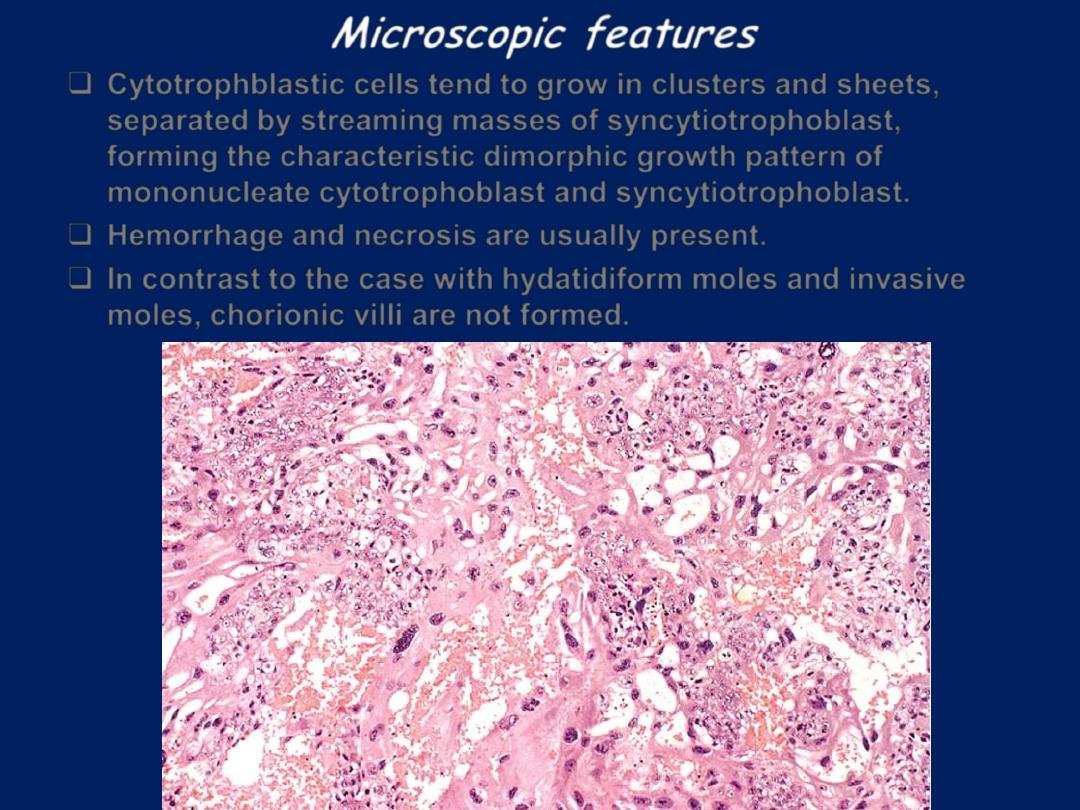

Microscopic features

Cytotrophblastic cells tend to grow in clusters and sheets,

separated by streaming masses of syncytiotrophoblast,

forming the characteristic dimorphic growth pattern of

mononucleate cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast.

Hemorrhage and necrosis are usually present.

In contrast to the case with hydatidiform moles and invasive

moles, chorionic villi are not formed.

Choriocarcinoma uterus:There is an intimate admixture of malignant

syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast in choriocarcinoma. No

chorionic villi are seen