Baghdad College of Medicine / 4

th

grade

Student’s Name :

Dr. Saad Dakhil

Lec. 3

BLADDER CANCER

Tues. 5 / 4 / 2016

DONE BY : Ali Kareem

مكتب اشور لالستنساخ

2015 – 2016

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

2

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

M

ODULE

5: H

EMATURIA

K

EY

W

ORDS

: Hematuria, Cystoscopy, Urine Cytology, UTI, bladder cancer

L

EARNING

O

BJECTIVES

At the end of this clerkship, the learner will be able to:

1. Define microscopic hematuria.

2. Describe the proper technique for performing microscopic urinalysis.

3. Identify four risk factors that increase the likelihood of finding malignancy

during evaluation of microhematuria.

4. Explain the significance of finding red cell casts in patients with microscopic

hematuria.

5. Contrast the evaluation of hematuria in the low risk patient with that of high-

risk patient.

6. Identify the indications for screening urinalyses in the general population.

D

EFINITION

Hematuria is defined as the presence of red blood cells in the urine. When visible to

the patient, it is termed gross hematuria and is usually alarming to patients.

Microscopic hematuria is that detected by the dipstick method or microscopic

examination of the urinary sediment.

The dipstick method to detect hematuria depends on the ability of hemoglobin to

oxidize a chromogen indicator with the degree of the indicator color change

proportional to the degree of hematuria

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=24#s1). Dipsticks have a

sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 75% and positive results should be confirmed

with a microscopic examination of the urine. Free hemoglobin, myoglobin and certain

antiseptic solutions (povidone-iodine) will also give positive readings. Knowing the

serum myoglobin level and results of the microscopic urinalysis will help differentiate

these confounders. The presence of significant proteinuria (2+ or greater) suggests a

nephrologic origin for hematuria.

Microscopic examination of urine is performed on 10 mL of a midstream, clean-catch

specimen that has been centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000 rpm. The sediment is

resuspended and examined under high power magnification. With this method,

microscopic hematuria is defined as > 3 red blood cells per high-powered field

(rbc/hpf) on two of three specimens.

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

3

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Figure 1: Red blood cells observed on high power microscopy of urine

sediment.

The presence of red cell casts, dysmorphic red blood cells, leukocytes, bacteria and

crystals should also be included in the report.

E

PIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of microscopic hematuria ranges from 1-20% depending on the

population studied. The likelihood of finding significant urologic disease in these

patients also varies with associated risk factors which include:

Even though the likelihood of documenting a urologic malignancy in patients referred

for microscopic hematuria is approximately 10%, no major health organization

currently recommends routine screening for microhematuria in asymptomatic

patients. Instead, the decision to obtain a urinalysis (dipstick or microscopic) is based

on the interpretation of clinical findings by the evaluating physician.

Table 1 – Risk Factors for Hematuria

Age >40 years

Male gender

History of cigarette smoking

History of chemical exposure (cyclophosphamide, benzenes, aromatic amines)

History of pelvic radiation

Irritative voiding symptoms (urgency, frequency, dysuria)

Prior urologic disease or treatment

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

4

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

E

TIOLOGY

The source of red blood cells in the urine can be from anywhere in the urinary tract

between the kidney glomerulus and the urethral meatus (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Human urinary tract anatomy that

is at risk when hematuria is found. From:

Nlm.nih.gov

Causes of hematuria may be

generally grouped into the site of

origin: Glomerular or Nonglomerular. Glomerular causes generally arise from the

kidney itself. Nonglomerular etiologies can be further subdivided by whether the

process is located in the upper urinary tract (kidney and ureter) or lower urinary tract

(bladder and urethra) (Figure 2). In general, urologists are concerned with structural

and pathologic conditions that are visible on imaging and endoscopic examination

whereas glomerular hematuria is the purview of nephrologists.

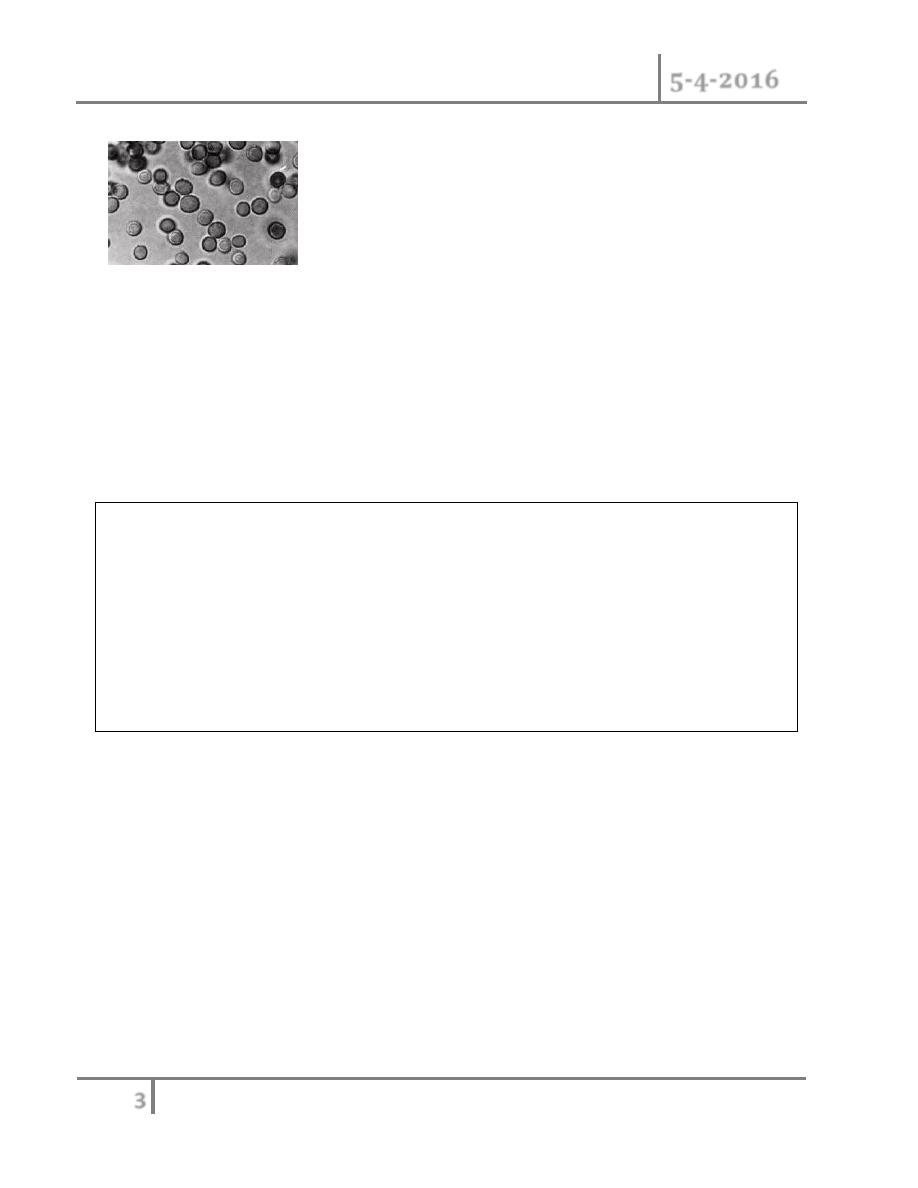

Urinary findings suggestive of a glomerular source for the patient’s hematuria include

red cell casts, dysmorphic red blood cells (Figure 3) and significant proteinuria.

Figure 3: Example of dysmorphic red blood cells consistent with renal or

glomerular hematuria.

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

5

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

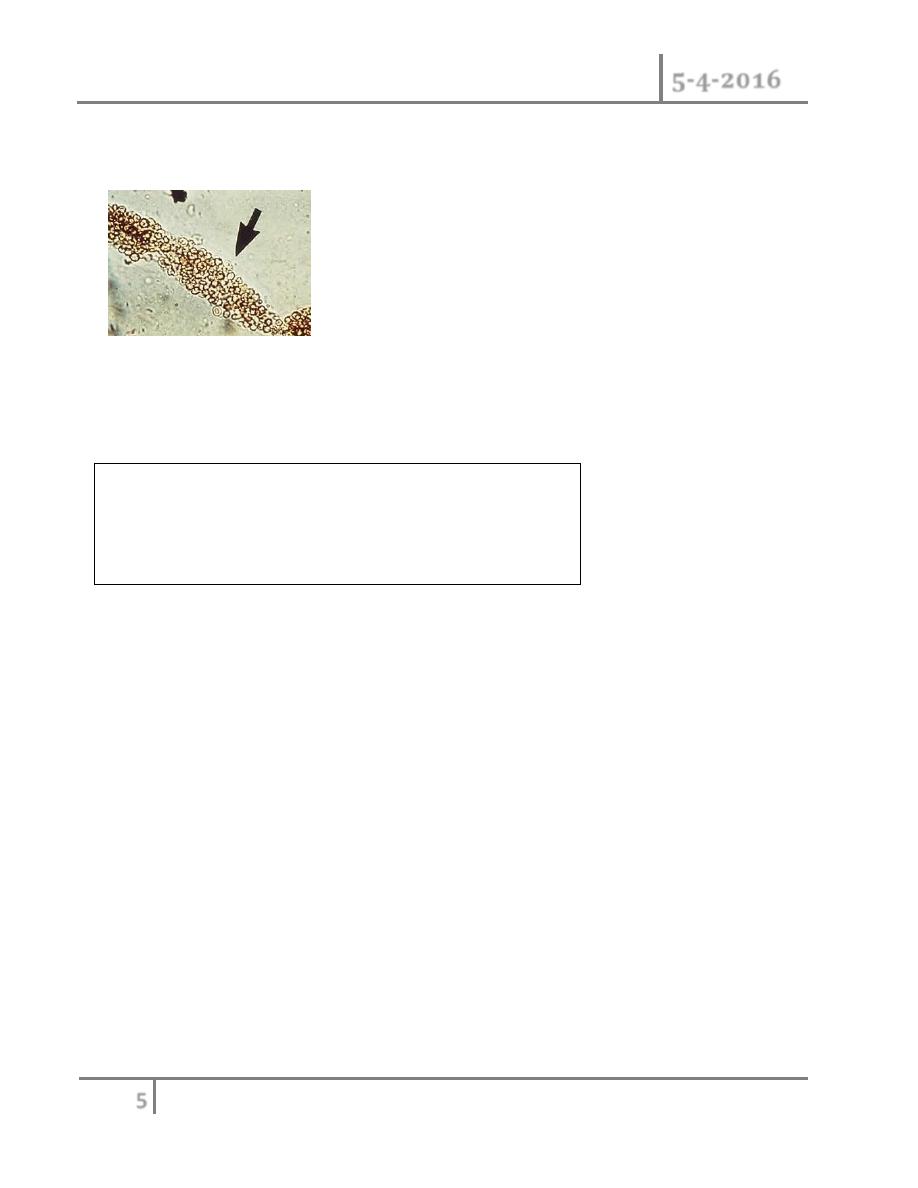

The presence of red cell casts in the urinary sediment is strong evidence for

glomerular hematuria.

Figure 4: Example of a red cell cast (arrow) in the urinary sediment.

Although protein may enter the urine along with the red blood cells regardless of the

origin of the hematuria, significant proteinuria (>1,000 mg/24 hours) likely indicates a

renal parenchymal process and should prompt consultation with a nephrologist. The

more common causes of glomerular hematuria are listed in Table 2. A more

comprehensive list is found in references 2 and 4.

Berger’s disease is the most common cause of asymptomatic glomerular

microhematuria and, in the absence of significant proteinuria, typically follows a

benign course. There is no proven treatment for the condition although fish oils may

benefit patients with progressive disease.

Causes of non-glomerular hematuria are often classified by location. The more

commonly encountered upper and lower urinary tract etiologies are listed in Table 3.

Although transitional cell carcinoma involving the urinary bladder is the most common

malignancy discovered in patients with asymptomatic microhematuria, a benign

process is far more the more likely explanation for the problem. In particular, urinary

tract infection, urinary tract stones and prostatic enlargement occur more frequently

than urologic malignancies.

Table 2 – Common Causes of Glomerular Hematuria

IgA nephropathy (Berger’s disease)

Thin glomerular basement membrane disease

Hereditary nephritis (Alport’s syndrome)

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

6

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Excessive anticoagulation from oral anticoagulation therapy does not lead to de novo

hematuria. However, the degree and duration of hematuria from another cause may

be influenced by such therapy.

E

VALUATION

The cornerstone of evaluating patients with hematuria is a thorough medical history

and directed physical examination. A prior history of urologic disease or interventions

is an important feature. Also, the presence of flank pain, fever or urinary symptoms

such as dysuria, frequency and urgency should be noted

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=67#DIAGNOSIS AND

STAGING). Association with other activities (menses, physical exertion, etc.) may

suggest an etiology for the patient’s hematuria. Pelvic irradiation and certain

chemotherapeutic agents, in particular cyclophosphamide and mitotane, have been

associated with hemorrhagic cystitis. Both cigarette smoking and occupational

exposures to aniline dyes and aromatic amines used in certain manufacturing

processes increase the risk of bladder cancer.

The presence of edema and cardiac arrhythmias may suggest the nephrotic syndrome

Table 3 – Common Causes of Non-Glomerular Hematuria

Upper Tract

Urolithiasis

Pyelonephritis

Renal cell cancer

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=48#s4)

Transitional cell carcinoma

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=45)

Urinary obstruction

Benign hematuria

Lower Tract

Bacterial cystitis (UTI)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Strenuous exercise (“marathon runner’s hematuria”)

Transitional cell carcinoma

Spurious hematuria (e.g. menses)

Instrumentation

Benign hematuria

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

7

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

and atrial fibrillation (with the possibility of renal embolization), respectively.

Costovertebral angle tenderness is suggestive of ureteral obstruction, often secondary

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

8

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

to stone disease, in the afebrile patient. When fever and flank tenderness are both

present the diagnosis of pyelonephritis should be entertained.

If the patient has not had a formal microscopic urinalysis this should also be part of

the initial evaluation

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=24#s1)

. As

noted earlier, the dipstick urinalysis may yield false-positive results in patients with

myoglobinuria. Also, some patients may present with “red urine” relating to dietary

intake or medication use (phenazopyridine) and these cases of spurious hematuria

may reveal a normal urinalysis. Understand, however, that hematuria may be

intermittent in patients with significant urologic disease and a repeat urinalysis

should be obtained if clinical suspicion is present.

In addition to identifying the number of red blood cells per high-powered field, the

presence or absence of red cell casts and/or dysmorphic red blood cells, the presence

of white blood cells and bacteria in the urinalysis may suggest infection. If infection is

suspected, a confirmatory urine culture should be obtained and a repeat urinalysis

performed after the infection has been treated. Patients with findings consistent with

glomerular hematuria should be referred to nephrology for further evaluation.

Based on the history and physical examination, including the urinalysis, patients with

nonglomerular hematuria may be stratified as high risk or low risk for significant

underlying urologic disease. Patients with gross hematuria or those with any of the

risk factors noted in Table 1 are considered high risk and should undergo a thorough

urologic evaluation. Patients with asymptomatic hematuria and no associated risk

factors are classified as low risk.

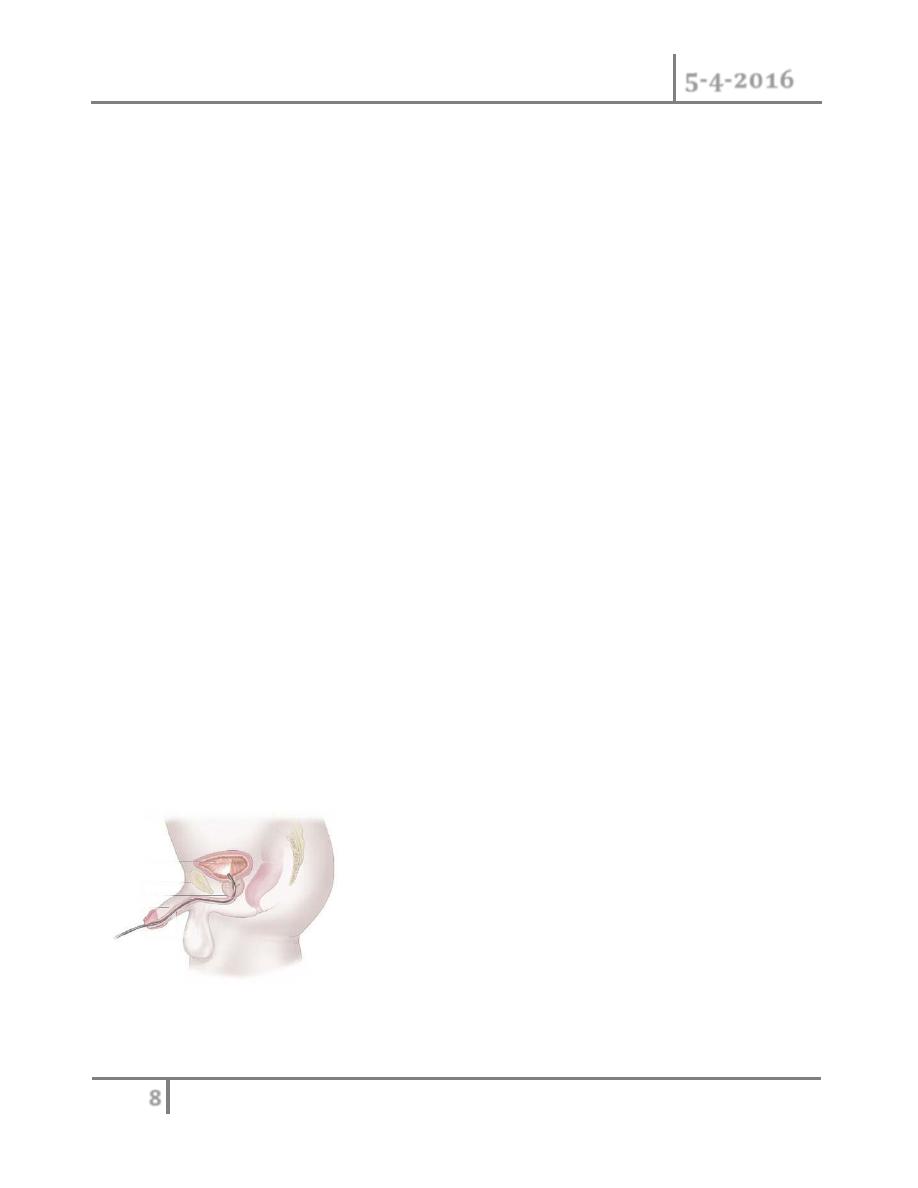

Because of the significant diseases that can cause nonglomerular hematuria, a

complete evaluation of the urinary tract is indicated. Imaging studies are used to

evaluate the upper urinary tract (kidneys and ureters) whereas urine cytology or

direct endoscopic visualization of the bladder and urethra are needed for the lower

urinary tract (Figure 5). The diagnostic studies selected depend on the risk factors for

significant disease.-

Figure 5: Flexible cystoscopy is used to examine the lower urinary tract in

patients with hematuria.

In low risk patients, renal ultrasonography and voided urine cytology are appropriate screening

studies for hematuria

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=65#s3)

. Ultrasound

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

9

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

examination of the kidneys will detect and characterize renal masses larger than 1 cm in

diameter.

Bladder Cancer Dr. Saad Dakhil

5-4-2016

10

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Also, clinically significant nephrolithiasis is likely to be found by ultrasound. Although

the ureters are difficult to image with ultrasonography, proximal hydronephrosis

(dilation) or unilateral absence of a “ureteral jet” of urine into the bladder suggest

ureteral obstruction and the need for additional studies. Cytologic examination of a

voided urine specimen is helpful to detect urothelial cancer

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=65#s3)

. Remember that urine

cytology does not screen for renal cell cancer (a reason for renal imaging) and may

reveal false negatives in the case of low-grade transitional cell cancers. Conversely,

positive urine cytology is usually indicative of transitional cell cancer and follow-up

endoscopic examination is necessary for a definitive diagnosis, and for localization

and staging. Low-risk patients may prefer to proceed directly to cystoscopy, which is

acceptable.

Patients with gross hematuria or associated risk factors should undergo contrast-

enhanced imaging of the kidneys and ureters in addition to cystourethroscopy and urine

cytology

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=45#s3)

Previously, the intravenous pyelogram (IVP) was the standard upper tract imaging

study for hematuria. However, this has been largely replaced by computerized

tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen and pelvis after administration of

intravenous contrast

(http://www.auanet.org/eforms/elearning/core/?topic=62#s4)

. CT

scanning is superior in differentiating cystic from solid masses within the kidney

compared to the IVP. Significant information about non-urologic structures is also

provided on CT imaging. Non-contrast helical CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis

is now the method of choice for detecting renal calculi. Before ordering any contrast

study (IVP or contrast-enhanced CT scan), the patient’s medications and allergies

should be reviewed and normal renal function documented.

If imaging studies suggest calyceal or ureteral pathology, then cystoscopic

examination may be performed in the operating room where retrograde ureterograms

can be done under fluoroscopic guidance. If imaging studies are normal, then

cystoscopy is performed in the office with topical anesthesia. At the time of

cystoscopy, a “bladder wash” (barbotage) can be sent for cytology, as the yield from

this test is higher than that of a voided urine specimen.

With this evaluation strategy, a cause for hematuria is identified in over 80% of cases.

Depending on their risk, up to 20% of patients with asymptomatic microhematuria are

discovered to have a urologic cancer. Patients with persistent hematuria after a

negative initial evaluation warrant repeat evaluation at 48-72 months since 3% of this

group will be subsequently diagnosed with a urologic malignancy. Despite these

findings, please remember that there are no evidence-based recommendations for

screening asymptomatic patients for hematuria.

R

EFERENCES

Asymptomatic Microscopic Hematuria in Adults: Summary of the AUA Best

Practice Policy Recommendations, Grossfeld GD, Wolf JS, Litwin MS, Hricak H,

Shuler CL, Agerter DC, Carroll PR, American Family Physician, 2001, 63 (6)

accessed May 7, 2011: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0315/p1145.html

Evaluation of the patient with hematuria, Yun EJ, Meng MV, Carroll PR,

Medical Clinics of North America, 2004, 88 (2)

Evaluation of hematuria in adults, Rose BD, Fletcher RH, UpToDate,

2007 Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9

th

edition, WB Saunders; 2007,

pages 97-100

Updated June, 2012

END OF THIS LECTURE …