Baghdad College of Medicine / 4

th

grade

Student’s Name :

Dr. Montadhar Al-Madani

Lec. 1 & 2

Nephrolithiasis

Thurs. & Mon.

31/3 & 4/4 2016

DONE BY : Ali Kareem

مكتب اشور لالستنساخ

2015 – 2016

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

2

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Nephrolithiasis

Composition of Renal Stones

1. Calcium oxalate (dihydrate and monohydrate): 70%.

2. Calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite): 20%.

3. Mixed calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate: 11% to 31%.

4. Uric acid: 8%.

5. Magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite): 6%.

6. Cystine: 2%.

7. Miscellaneous: xanthine, silicates, and drug metabo- lites, such as

indinavir (radiolucent on x-ray and CT scan).

Pathogenesis and Physiochemical Properties

GENETICS

1. Idiopathic hypercalciuria

o Polygenic

o Calcium salt stones

o Rare nephrocalcinosis

o Rare risk of end-stage renal disease

2. Primary hyperoxaluria types 1, 2, and 3

o Autosomal recessive

o Pure monohydrate calcium oxalate stones (whewellite)

o Nephrocalcinosis

o Risk of end-stage renal disease

3. Distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA)

o Autosomal recessive or dominant

o Apatite stones

o Nephrocalcinosis

o Risk of end-stage renal disease

4. Cystinuria

o Autosomal recessive associated with a defect on chromosome 2

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

3

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

o Cystine stones

o No nephrocalcinosis

o Risk of end-stage renal disease

5. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (HGPRT deficiency)

o X-linked recessive

o Uric acid stones

o No nephrocalcinosis

o Risk of end-stage renal disease

ENVIRONMENTAL

1. Dietary factors

o Normal dietary calcium intake is associated with a reduced risk of

calcium stones secondary to binding of intestinal oxalate.

o Increased calcium and vitamin D supplementation may in- crease

the risk of calcium stones.

o Increased dietary sodium intake is associated with an in- creased

risk of calcium and sodium urinary excretion, which leads to

increased calcium stones.

o Increased dietary animal protein intake may lead to in- creased

uric acid and calcium stones.

o Increased water intake is associated with a reduced risk of all

types of kidney stones.

2. Obesity

o Obesity and weight gain are associated with an increased risk of

developing kidney stones.

3. Diabetes

o Diabetes is a risk factor for the development of kidney stones.

o Insulin resistance may lead to altered acidification of the urine and

increased urinary calcium excretion.

4. Geographical factors

o The highest risk of developing kidney stones is in the south-

eastern United States; the lowest risk is in the northwestern United

States.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

4

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

o Stone incidence peaks approximately 1 to 2 months after highest

annual temperature.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF STONE FORMATION

1. Idiopathic calcium oxalate

a. Approximately 70% to 80% of incident stones are calcium

oxalate.

b. Initial event is precipitation of calcium phosphate on the renal

papilla as Randall plaques, which serve as a nucleus for

calcium oxalate precipitation and stone formation.

c. Calcium oxalate stones preferentially develop in acidic urine

(pH less than 6.0).

d. Development depends on supersaturation of both calcium and

oxalate within the urine.

2. Idiopathic hypercalciuria

a. Identified in 30% to 60% of calcium oxalate stone formers and in

5% to 10% of nonstone formers

b. The upper limit of normal for urinary calcium excretion is 250

mg/day for women and 300 mg/day for men.

c. Need to exclude hypercalcemia, vitamin D excess, hyper-

thyroidism, sarcoidosis, and neoplasm.

d. Diagnosed via exclusion in patients with a normal serum calcium

but elevated urinary calcium on a random diet.

3. Absorptive hypercalciuria

a. Increased jejunal absorption of calcium possibly caused by

elevated calcitriol (1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D 3 ) levels and

increased vitamin D receptor expression.

b. Divided into type I, II and III, depending on whether uri- nary

calcium levels can be affected by calcium in the diet (type I and

II) or renal phosphate leak leading to increased calcium

absorption (type III).

c. Increased calcium absorption leads to a higher filtered load of

calcium delivered to the renal tubule.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

5

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

d. The treatment for each subtype is generally the same, so de-

termining which type (often requiring inpatient evaluation) is

no longer necessary.

e. Normal serum calcium

4. Renal hypercalciuria

a. Impaired proximal tubular reabsorption of calcium leads to

renal calcium wasting.

b. Normal serum calcium; hypercalciuria persists despite a

calcium restricted diet.

c. Distinguished from primary hyperparathyroidism by normal

serum calcium levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

5. Resorptive hypercalciuria

a. Primary hyperparathyroidism is the underlying mechanism.

b. Increased PTH levels cause bone resorption and intestinal

calcium absorption, which leads to elevated serum calcium that

exceeds the reabsorptive capacity of the renal tubule.

c. Normal to slightly elevated serum calcium

6. Hypercalcemic hypercalciuria

a. Primary hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, sarcoid- osis,

vitamin D excess, milk alkali syndrome, immobiliza- tion, and

malignancy

7. Hyperoxaluria

a. The upper limit of normal for urinary oxalate excretion is 45 mg/d

in women and 55 mg/d in men.

b. Acts as a potent inhibitor of stone formation by complexing with

calcium

c. Dietary hyperoxaluria is related to increased consumption of

oxalate-rich foods, and/or a low-calcium diet, which by reducing

the availability of intestinal calcium to complex to oxalate, allows

an increased rate of free oxalate absorption by the gut.

d. Enteric hyperoxaluria can be caused by small bowel disease or

loss, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or diarrhea, all of which

reduce small bowel fat absorption, leading to an increase in fat

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

6

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

complexing with calcium, and thereby facili- tating free oxalate

absorption by the colon.

e. Primary hyperoxaluria is a genetic disorder in one of two genes,

which results in increased production or urinary ex- cretion of

oxalate.

8. Hypocitraturia

a. The lower limit of normal is less than 500 mg/d for women and 350

mg/d for men.

b. Acts as an inhibitor of stone formation by complexing with

calcium.

c. Citrate is regulated by tubular reabsorption, and reab- sorption

varies with urinary pH. In acidic conditions, tubular reabsorption

is enhanced, which lowers urinary citrate levels.

d. Diseases that cause acidosis, such as chronic diarrhea or distal

RTA, cause lower urinary citrate levels. Thiazide therapy can also

reduce citrate levels via potassium depletion.

e. In the majority of patients with hypocitraturia, no etiol- ogy is

identified, and these patients are classified as having idiopathic

hypocitraturia.

9. Hyperuricosuria/uric acid stones

a. Approximately 5% to 10% of incident stones are uric acid.

b. The upper limit of normal is greater than 750 mg/d for women and

800 mg/d for men.

c. Uric acid is a promoter for calcium oxalate stone forma- tion by

serving as a nucleus for crystal generation and also by reducing

the solubility of calcium oxalate.

d. A low urinary pH is critical for uric acid stone forma- tion. At a

urinary pH less than 5.5, uric acid exists in its insoluble

undissociated form, which facilitates uric acid stone formation. As

the urinary pH increases, the dissociated monosodium urate

crystals are predominant and serve as a nucleus for calcium-

containing stone formation.

e. Increased uric acid production is common in patients with a high

dietary intake of animal protein, in myeloprolifera- tive disorders,

and in gout. However, uric acid stone for- mation is also common

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

7

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

in patients with diabetes and the metabolic syndrome presumably

caused by insulin resis- tance, which impairs renal ammonia

excretion necessary for urinary alkalization.

10. Cystinuria

a. In both men and women, urinary cystine excretion exceeds 350 mg/

d.

b. Caused by autosomal recessive disorder involving the SLC3A1

amino acid transporter gene on chromosome 2

c. The dibasic amino acid transporter, which is located within the

tubular epithelium, facilitates reabsorption of dibasic amino acids,

such as cystine, ornithine, lysine, and arginine, (COLA). A defect

in this enzyme leads to de- creased cystine reabsorption and

increased urinary excre- tion of cystine.

d. Cystine solubility rises with increasing pH and urinary volume.

e. Positive urine cyanide-nitroprusside colorimetric reaction is a

qualitative screen.

11. Calcium phosphate stones

a. Approximately 12% to 30% of incident stones are cal- cium

phosphate

b. Calcium phosphate stones preferentially develop in alka- line

urine (pH greater than 7.5).

c. Calcium phosphate stones can be present as either apatite or

brushite (calcium phosphate monohydrate).

d. Overalkalinization with potassium citrate for hypercalci- uria can

sometimes lead to calcium phosphate stones.

12. Struvite stones/triple phosphate/infection stones

a. Approximately 5% of incident stones are struvite.

b. Struvite stones are composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate

and calcium phosphate. They may also contain a nidus of another

stone composition.

c. Often grow to encompass large areas in the collection sys- tem or

staghorn calculi.

d. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) with urease splitting organisms,

which include Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

8

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

aureus, Pseudomonas spp., and Ureaplasma spp., are required to

split urea into ammonia, bicarbonate, and carbonate.

e. A urinary pH greater than 7.2 is required for struvite stone

formation.

f. Conditions that predispose to urinary tract infections in- crease the

likelihood of struvite stone formation. Struvite stones are common

in patients with spinal cord injuries and neurogenic bladders.

Clinical Manifestations of Nephrolithiasis

A. Asymptomatic kidney stones are found in 8% to 10% of screening

populations undergoing a CT scan for unrelated reasons.

B. Pain is the most common presenting symptom in the majority of patients.

1. The stone produces ureteral spasms and obstructs the flow of

urine, which causes a resultant distention of the ureter,

pyelocalyceal system, and ultimately the renal capsule to produce

pain.

2. Renal colic is characterized by a sudden onset of severe flank

pain, which often lasts 20 to 60 minutes. The pain is paroxysmal,

and patients are often restless and unable to get comfortable.

3. Three main sites of anatomic narrowing or obstruction are within

the ureter: the ureteropelvic junction, the lumbar ureter at the

crossing of the iliac vessels, and the ureterovesical junction.

4. The location of pain generally correlates with these sites of

anatomic narrowing: the ureteropelvic junction pro- duces classic

flank pain, the midureter at the level of the iliac vessels produces

generalized lower abdominal dis- comfort, and the ureterovesical

junction produces groin or referred testes/labia majora pain.

C. Associated nausea and vomiting are frequent. Fever and chills are

common with concomitant UTI.

D. Dysuria or strangury, which is the desire to void but with urgency,

frequency, straining, and small voided vol- umes, is possible with stones

located at the ureterovesical junction.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

9

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

o Pyelonephritis: Fever with associated flank pain Musculoskeletal pain:

Pain with movement

o Appendicitis: Right lower quadrant tenderness at McBurney point

Cholecystitis: Right upper quadrant tenderness with Murphy sign

o Colitis/diverticulitis: Left lower quadrant tenderness with GI symptoms

o Testicular torsion: Abnormal testicular exam with high-riding testicle

Ovarian torsion/ruptured ovarian cyst: Adnexal tenderness

Evaluation of Patients with Nephrolithiasis

1. General considerations

a. All patients in the acute phase of renal colic should have a history

and physical, a urinalysis, a urine culture if uri- nalysis

demonstrates bacteruria or nitrites, and a serum cre- atinine. If

the patient presents with fever, then a complete blood count should

also be included.

b. All patients with a first stone episode should undergo a ba- sic

evaluation with a medical history including family his- tory,

dietary history, and medications; physical exam and ultrasound;

blood analysis with creatinine, calcium, and uric acid; urinalysis

and culture; and stone analysis.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

10

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

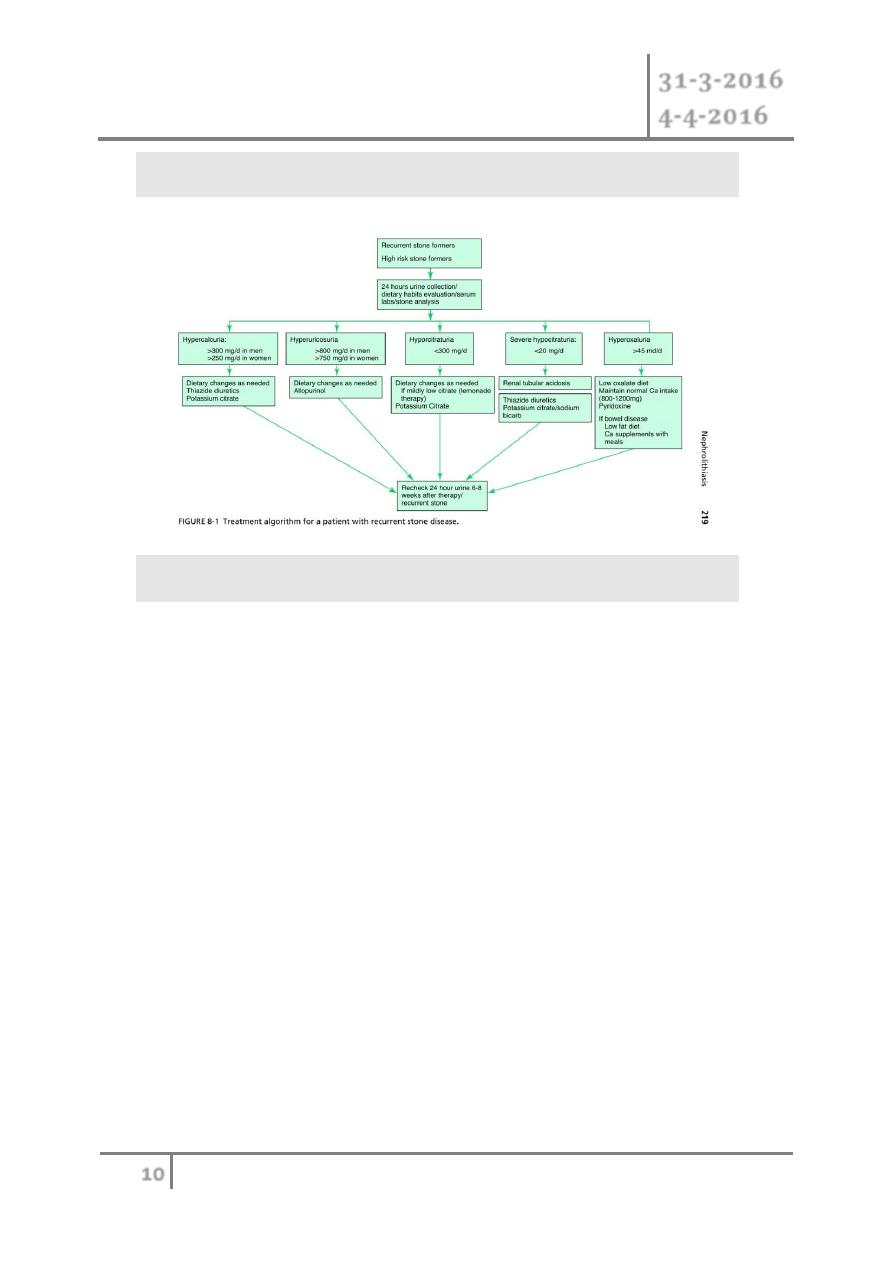

c. Patients at high risk include those with a family history of

nephrolithiasis, recurrent stone formation, large stone burden,

residual stone fragments after therapy, solitary kidney, metabolic,

or genetic abnormalities known to predispose to stone formation,

stones other than calcium oxalate, and children given a higher rate

of an underlying metabolic, anatomic, and/or functional voiding

abnormality. These patients they should undergo the basic

evaluation, plus two 24-hour urine collections, at least 4 weeks

following the acute stone episode. Further therapy will be

guided by the stone analysis and 24-hour urine collections.

2. Medical history

a. General medical history is mandatory in all stone formers.

b. Past medical history with a specific focus on diseases known to

contribute to stone formation, including inflammatory bowel

disease, previous bowel resection, or gastric bypass,

hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, RTA, and gout.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

11

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

c. Family history is of particular importance because a positive

family history is a risk factor for incident stone formation and

recurrence.

d. Review medications for drugs known to increase stone for- mation,

such as acetazolamide, ascorbic acid, corticoste- roids, calcium-

containing antacids, triamterene, acyclovir, and indinavir.

e. Dietary history can also be relevant, especially in those with high-

or low-calcium diets, diets high in animal protein, and diets with

significant sodium intake.

3. Physical exam

a. May provide clues to underlying systemic diseases.

4. Laboratory evaluation

a. Urinalysis

1- Specific gravity may indicate relative hydration status.

2- Calcium oxalate stones preferentially form in a relatively

acidic pH (less than 6.0), whereas calcium phosphate stones

preferentially form in a relatively alkaline pH (greater than

7.5). A low pH (less than 5.5) is man- datory for uric acid

stone formation. A high pH (greater than 7.2) is critical for

struvite stone formation. A pH constantly greater than 5.8

may suggest an RTA.

o Microscopy may reveal red blood cells, white blood cells (WBCs), and

bacteria.

o Crystalluria can define stone type: Hexagonal crystals are cystine, coffin

lid crystals are calcium phosphate, and rhomboidal crystals are uric

acid.

b. Urine culture is mandatory if microscopy reveals bacte- riuria, if

struvite stones are suspected, or if symptoms or signs of infection

are present.

c. Electrolytes

1- Calcium (ionized or calcium with albumin): Elevated calcium

may suggest hyperparathyroidism, and a para- thyroid

hormone (PTH) blood test should be done.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

12

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

2- Uric Acid: Elevated uric acid is common in gout and, in

conjunction with a radiolucent stone, is suggestive of uric acid

nephrolithiasis.

d. A complete blood count (CBC) may show mild peripheral

leukocytosis. WBC counts higher than 15,000/mm 3 may suggest

an active infection.

e. Ammonium chloride load test: Identifies distal or Type I RTA.

Oral ammonium chloride load (0.1 gm/ kg body weight) given over

30 minutes will not raise the urinary pH greater than 5.4 if a Type

I RTA is present.

f. Sodium nitroprusside test: Identifies cystinuria. Addition of

sodium nitroprusside to urine with cystine concentration higher

than 75 mg/L alters the urine color to purple-red.

g. 24-Hour urine collection: Typically one to two 24- hour urine

collections are obtained at least 6 weeks after an acute stone event

or following initiation of medical therapy or dietary modification.

Collection is done to determine total urine volume, pH, creatinine,

calcium, oxalate, uric acid, citrate, magnesium, sodium,

potassium, phosphorus, sulfate, urea, and ammonia. Cystine is

also determined if a cystine screening test is positive.

Supersaturation indices are also calculated. An adequate

collection is determined by total creatinine, which is 15-19 mg/kg

for women and 20-24 mg/kg for men.

h. Stone analysis: Performed either with infrared spec- troscopy or

x-ray diffraction. It provides information about the underlying

metabolic, genetic, or dietary abnormality.

5. Imaging considerations

a. A noncontrast CT scan is the recommended initial imaging

modality for an acute stone episode. A noncontrast CT scan has a

sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 97% in detect- ing ureteral

calculi. A low-dose noncontrast CT scan (less than 4 mSv) is

preferred in patients with a body mass index (BMI) less than 30.

When a ureteral stone is visualized on a noncontrast CT scan

b. A renal bladder ultrasound is the recommended initial im- aging

modality in both children and pregnant patients in order to limit

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

13

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

ionizing radiation. Ultrasonography has a median sensitivity of

61% and a specificity of 97%. If ultra- sonography is equivocal,

and the clinical suspicion is high for nephrolithiasis, then a low-

dose noncontrast CT scan may be performed in both children and

pregnant patients.

c. Plain film of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB) is also

routinely used. Conventional radiography with a KUB has a

median sensitivity of 57% and a specificity of 76%. Pure uric acid,

cystine, indinavir, and xanthine stones are radio- lucent, and are

not visible on KUB.

d. Intravenous pyelography (IVP) was commonly utilized for

diagnosis of stone disease because it could read- ily identify

radiolucent stones and define calyceal anatomy. It has a median

sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 95%. However, CT has

largely replaced IVP.

e. Magnetic resonance imaging is generally not performed for

urolithiasis because of cost, low sensitivity, and time needed to

acquire images.

f. A combination of ultrasonography and KUB is recom- mended for

monitoring patients with known radiopaqueureteral calculi on

medical expulsion therapy because this limits costs and radiation

exposure. Those with radiolucent stones will require a low-dose

noncontrast CT scan.

Management of Nephrolithiasis

MEDICAL THERAPY

1. All stone formers

a. High fluid intake of 2.5-3.0 L/day with urine volume greater

than 2 L/ day

b. Normal calcium diet of 800-1200 mg/day, preferably not

through supplements. Avoid excess calcium supplementa- tion;

however calcium citrate is preferred if indicated.

c. Limit sodium to 4-5 g/day.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

14

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

d. Limit animal protein to 0.8-1.0 g/kg/day.

e. Limit oxalate-rich foods.

f. Maintain a normal BMI and physical activity.

g. Targeted therapy depending on underlying metabolic ab-

normality and/or 24-hour urine collection results

2. Calcium oxalate stones

a. Dietary hyperoxaluria: Limit oxalate-rich foods.

b. Enteric hyperoxaluria: Limit oxalate-rich foods and cal- cium

supplementation with greater than 500 mg/day.

c. Primary hyperoxaluria: Pyridoxine can decrease endog- enous

production of oxalate. The dose is 100-800 mg/day.

d. Hypocitraturia: Potassium citrate both raises the uri- nary pH out

of the stone-forming range and restores the normal urinary citrate

concentration. Sodium bicarbonate may also be used, if unable to

tolerate potassium supple- mentation.

e. Hypercalciuria: Thiazide diuretics, which inhibit a sodium-

chloride co-transporter, therefore enhancing distal tubular sodium

reabsorption via the sodium-calcium co-transporter to promote

tubular calcium reabsorption. Thiazides de- crease urinary

calcium by as much as 150 mg/day.

3. Calcium phosphate stones

a. Primary hyperparathyroidism: Requires parathyroidectomy.

b. Distal RTA (Type I): Potassium citrate or sodium bicarbon- ate to

restore the natural pH balance.

4. Struvite/infection stones

a. Total stone removal because each fragment harbors urease-

producing bacteria and serves as a nidus for further stone growth.

b. Appropriate antibiotic therapy to eradicate the urease-pro- ducing

bacteria

c. Restoration of normal pH with urinary acidification with L-

methionine or inhibition of urease enzyme with acetohy- droxamic

acid

5. Uric acid stones

a. Low animal protein diet

b. Specific therapy depends on 24-hour urine collection results.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

15

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

c. Alkalinization of the urine with potassium citrate or so- dium

bicarbonate for stone dissolution is possible with a pH of 7.0 to

7.2 and for maintenance of a stone-free state with a pH of 6.2 to

6.8.

d. Hyperuricosuria (with or without hyperuricemia): Allopurinol at

100-300 mg/day, which inhibits xanthine oxidase to reduce uric

acid production.

6. Cystine stones

a. Increase daily fluid intake to 3.5 to 4.0 L/day.

b. Specific therapy depends on 24-hour urine collection results.

c. Alkalinization of the urine with potassium citrate or so- dium

bicarbonate above a pH of 7.5 to improve solubility of cystine

threefold

d. d. D-penicillamine is a chelating agent that forms a disulbond

with cysteine to produce a more soluble compound, thereby

preventing the formation of cysteine into the insoluble, stone

forming, cystine. Alpha-mercaptopropionyl-glycine (tiopronin) is

the preferred alternative to D-penicillamine, as it has a better

safety and efficacy profile. Alpha- mercaptopropionyl-glycine

reduces the disulfide bond of cystine to form the more soluble

cysteine, again reducing stone formation. Lastly, captopril is an

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, which can reduce

cystine, but its role in therapy is not yet well defined.

ACUTE RENAL COLIC

1. General considerations

a. Primary considerations include symptomatic control with

analgesics, antiemetics, and adequate hydration.

b. First-line analgesia is generally a nonsteroidal antiinflam-

matory, such as ketorolac.

c. Patients should be instructed to sieve their urine for collec- tion of

stone fragments.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

16

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

d. Spontaneous stone passage occurs in 80% of patients with sizes

less than 4 mm. With sizes greater than 10 mm, there is a low

probability of spontaneous passage.

e. Referral to a urologist is necessary with persistent pain, high-

grade obstruction, bilateral obstruction, presence of infection,

solitary kidney, abnormal anatomy, failure of conservative

management, large stone burden, pregnancy, or in children.

2. Medical expulsive therapy

a. Alpha-blockers, such as tamsulosin, and calcium channel blockers

(nifedipine) or steroids can facilitate stone passage via ureteral

smooth muscle relaxation.

b. Medical expulsive therapy (MET) is acceptable in patients with

ureteral calculi less than 10 mm who have well- controlled pain,

no evidence of infection, adequate renal function, and no other

contraindications to the therapy.

SURGICAL THERAPY

1. Shock wave lithotripsy (SWL):

a. Shock waves are high-energy focused-pressure waves that can travel

in air or water. When passing through two dif- ferent mediums of

different acoustic impedance, energy is released, which results in the

fragmentation of stones. Shock waves travel harmlessly through

substances of the same acoustic density. Because water and body

tissues have the same density, shock waves can travel safely through

skin and internal tissues. The stone is a different acoustic density and,

when the shock waves hit it, they shatter and pulverize it. Urinary

stones are thus fragmented, facilitating in their spontaneous passage.

b. Treatment success depends on stone size, location, composi- tion,

hardness, and body habitus. For renal stones, upper or middle polar

stones are ideally treated with SWL, whereas lower pole stones have

a clearance rate as low as 35%.

c. Ideally all stones less than 1 cm in any location in the kid- ney can be

treated with SWL.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

17

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

d. Contraindications of SWL include (absolute) pregnancy, bleeding

diathesis, and obstruction below the level of the stone; and (relative)

calcified arteries and/or aneurysms and cardiac pacemaker.

e. Complications of SWL include skin bruising, subscapular and

perinephric hemorrhage, pancreatitis, urosepsis, and Steinstrasse

(“street of stone,” which may accumulate in the ureter and cause

obstruction).

2. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

a. a. The technique is establishment of access at a lower pole ca- lyx,

dilation of the tract with a balloon dilator or Amplatz dilators

under fluoroscopy, and stone removal with grasp- ers or its

fragmentation using electrohydraulic, ultrasonic, or laser

lithotripsy. A nephrostomy tube or ureteral stent is left for

drainage.

b. d. Additional candidates for PCNL include cystine calculi, which

are large volume and resistant to SWL, and anatomic

abnormalities, such as those with ureteropelvic junction (UPJ)

obstruction, caliceal diverticula, obstructed infundib- ula

(hydrocalyx), ureteral obstruction, malformed kidneys (e.g.,

horseshoe and pelvic), and obstructive or large adja- cent renal

cysts.

c. e. Contraindications of PCNL include uncontrolled bleeding

diathesis, untreated urinary tract infection (UTI), and in- ability to

obtain optimal access for PCNL because of obe- sity,

splenomegaly, or interposition of colon.

d. f. Complications of PCNL include hemorrhage (5% to 12%),

perforation, and extravasation (5.4% to 26%), damage to adjacent

organs (1%), ureteral obstruction (1.7% to 4.9%), and

infection/urosepsis (3%).

3. Retrograde intrarenal surgery (ureteroscopy [URS])

a. Instrumentation includes both rigid and flexible uretero- scopes.

Rigid ureteroscopes are ideally suited for access to the distal

ureter but can be utilized up to the proximal ureter. Flexible

ureteroscopes are ideally suited for ureteral and intrarenal

access.

Nephrolithiasis Dr. Montadher Al-Madani

31-3-2016

4-4-2016

18

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

b. URS may be safely performed in patients with morbid obe- sity,

pregnancy, and bleeding diathesis.

c. Complications include failure to retrieve the stone, muco- sal

abrasions, false passages, ureteral perforation, complete ureteral

avulsion, and ureteral stricture.

4. Open/laparoscopic/robotic surgery

a. Since the introduction of minimally invasive techniques such as

SWL, URS, and PCNL, open surgery has been re- duced to rates

of 1% to 5%.

b. Indications for open stone surgery include complex stone burden,

treatment failure with endoscopic techniques, ana- tomic

abnormalities, and a nonfunctioning kidney.

c. Laparoscopic or robotic surgery can be used in place of open

techniques, but because of the complexity and rarity of these

procedures, they are generally referred to centers of excellence.

END OF THIS LECTURE …