Baghdad College of Medicine / 4

th

grade

Student’s Name :

Dr. Basim Rassam

Lec. 3

Acute Peritonitis & intra

abdominal abscesses

Thurs. 19 / 11 / 2015

DONE BY : Ali Kareem

مكتب اشور لالستنساخ

2015 – 2016

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

2

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Acute Peritonitis

ACUTE PERITONITIS AND INTRA-ABDOMINAL AND PELVIC

ABSCESSES

INTRA-ABDOMINAL infections result in two major manifestations..

1-early or diffuse infection result in localized or generalized peritonitis.

2-late and localized infection produces.. intra-abdominal and pelvic abscesses.

Learning Objectives

To recognize and understand:

* The clinical features of localized and generalized peritonitis.

* The common causes and complications of peritonitis.

* The principles of surgical management in patients with peritonitis.

* The clinical presentations and treatment of abdominal/pelvic abscesses.

* The clinical presentations of tuberculosis peritonitis.

The Peritoneum:

The peritoneal membrane is conveniently divided into two parts – the visceral

peritoneum surrounding the viscera and the parietal peritoneum lining the other

surfaces of the cavity. The peritoneum had a number of functions.

Summary box .

Functions of the peritoneum

o Pain perception (parietal peritoneum).

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

3

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

o Visceral lubrication.

o Fluid and particulate absorption.

o Inflammatory and immune responses.

o Fibrinolytic activity.

The parietal portion is richly supplied with nerves and, when irritated,

causes severe pain accurately localized to the affected area. The visceral

peritoneum, in contrast, is poorly supplied with nerves and its irritation

causes vague pain that is usually located to the midline.

The peritoneal cavity is the largest cavity in the body, the surface area of its

lining membrane (2m2 in an adult) being nearly equal to that of the skin.

The peritoneal membrane is composed of flattened polyhedral cells

(mesothelium), one layer thick, resting upon a thin layer of fibroblastic

tissue. Beneath the peritoneum, supported by a small amount of areola

tissue, lies a network of lymphatic vessels and rich plexuses of capillary

blood vessels from which all absorption and exudation must occur. In

health, only a few milliliters of peritoneal fluid is found in the peritoneal

cavity. The fluid is pale yellow, somewhat viscid and contains lymphocytes

and other leucocytes; it lubricates the viscera, allowing easy movement and

peristalsis.

In the peritonea space, mobile gas-filled structures float upwards, as does

free air(„gas‟). In the erect position, when free fluid is present in the

peritoneal cavity, pressure is reduced in the upper abdomen compared with

the lower abdomen. When air is introduced, it rises, allowing all of the

abdominal contents to sink.

During expiration, intra-abdominal pressure is reduced and peritoneal fluid,

aided by capillary attraction, travels in an upward direction towards the

diaphragm. Experimental evidence shows that particulate matter and

bacteria are absorbed within a few minutes into the lymphatic network

through a number of „pores‟ within the diaphragmatic peritoneum. This

upward movement of peritoneal fluids is responsible for the occurrence of

many subphrenic abscesses.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

4

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

The peritoneum has the capacity to absorb large volumes of fluid: this

ability is used during peritoneal dialysis in the treatment of renal failure.

But the peritoneum can also produce an inflammatory exudates when

injured.

Summary box .

CAUSES OF PERITONIAL INFLAMMATORY EXUDATE..

o Bacterial infection, e.g. appendicitis, tuberculosis.

o Chemical injury, e.g. bile peritonitis.

o Ischemic injury, e.g. strangulated bowel, vascular occlusion.

o Direct trauma, e.g. operation.

o Allergic reaction, e.g. starch peritonitis.

When a visceral perforation occurs, the free fluid that spills into the

peritoneal cavity runs downwards, largely directed by the normal peritoneal

attachments. For example, spillage from a perforated duodenal ulcer may

run down the right parabolic gutter.

When parietal peritoneal defects are created, healing occurs not from the

edges but by the development of new mesothelial cells throughout the

surface of the defect. In this way, large defects heal as rapidly as small

defects.

Acute Peritonitis

Most cases of peritonitis are caused by an invasion of the peritoneal cavity

by bacteria, so that when the term “peritonitis” is used without

qualification, bacterial peritonitis is implied. Bacterial peritonitis is usually

polymicrobial, both aerobic and anaerobic organisms being present. The

exception is primary peritonitis (“spontaneous” peritonitis), in which a pure

infection with streptococcal, pneumococcal or Haemophilus bacteria occurs.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

5

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Bacteriology

Bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract

The number of bacteria within the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract is

normally low until the distal small bowel is reached, whereas high

concentrations are found in the colon. However, disease (e.g. obstruction,

achlorhydria, diverticulitis) may increase proximal colonization. The biliary

and pancreatic tracts are normally free from bacteria, although they may be

infected in disease, e.g. gallstones. Peritoneal infection is usually caused by

two or more bacterial strains. Gram-negative bacteria contain end toxins

(lip polysaccharides) in their cell walls that have multiple toxic effects on

the host, primarily by causing the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

from host leucocytes. Systemic absorption of end toxin may produce end

toxic shock with hypotension and impaired tissue perfusion. Other bacteria

such as Clostridium wheelchair produce harmful serotoxins.

Bactericides are commonly found in peritonitis. These Gram-negative, non-

sporing organisms, although predominant in the lower intestine, often

escape detection because they are strictly anaerobic and slow to growth on

culture media unless there is an adequate carbon dioxide tension in the

anaerobic apparatus (Gillespie). In many laboratories, the culture is

discarded if there is no growth in 48 hours. These organisms are resistant to

penicillin and streptomycin but sensitive to metronidazole, clindamycin,

lincomycin and cephalosporin compounds. Since the widespread use of

metronidazole (Flagyl), Bacteroides infections have greatly diminished.

Non- gastrointestinal caused of peritonitis

o Pelvic infection via the fallopian tubes is responsible for a high proportion

of “non- gastrointestinal” infections.

o Immunodeficient patients, for example those with human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) infection or those on immunosuppressive treatment, may present

with opportunistic peritoneal infection, e.g. Mycobacterium avium –

intracellulare (MAI).

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

6

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Summary box .

Bacteria in peritonitis

1- Gastrointestinal source

o Escherichia coli

o Streptococci (aerobic and anaerobic)

o Bacteroides

o Clostridium

o Klebsiella pneumonia

o Staphylococcus

2- Other sources

3- Chlamydia

4- Gonococcus

5- β-Haemolytic streptococci

6- Pneumococcus

7- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Route of infection

o Infecting organisms may reach the peritoneal cavity via a number of

routes

Summary Box.

Paths to peritoneal infection

o Gastrointestinal perforation, e.g. perforated ulcer, diverticular perforation.

o Exogenous contamination, e.g. drains, open surgery, trauma.

o Transmural bacterial translocation (no perforation), e.g. inflammatory

bowel disease, appendicitis, ischaemic bowel.

o Female genital tract infection, e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease.

o Haematogenous spread (rare), e.g. septicaemia.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

7

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Even in patients with non-bacterial peritonitis (e.g. acute pancreatitis,

intrapertioneal rupture of the bladder or haemoperitoneum), the peritoneum

ofter becomes infected by transmural spread of organisms from the bowel,

and it is not long (often a matter of hours) before a bacterial peritonitis

develops. Most and many gastric perforations are also sterile at first;

intestinal perforations are usually infected from the beginning. The

proportion of anaerobic to aerobic organisms increase with passage of time.

Mortality reflects:

the degree and duration of peritoneal contamination;

the age of the patient

the general health of the patient;

the nature of the underlying cause.

Localized peritonitis

Anatomical, pathological and surgical factors may favour the localization of

peritonitis.

Anatomical

The greater sac of the peritoneum is divided into (1) the subphrenic, spaces

(2) the pelvis and (3) the peritoneal cavity proper. The last is divided into a

supracolic and an infrasonic compartment by the transverse colon and

transverse mescaline, which deters the spread of infection from one to the

other. When the supracolic compartment overflows, as is often the case

when a peptic ulcer perforates, it does so over the colon into the infrasonic

compartment or by way of the right parabolic gutter to the right iliac fosse

and hence to the pelvis.

Pathological

The clinical course is determined in part by the manner in which adhesions

form around the affected organ. Inflamed peritoneum loses its glistening

appearance and becomes reddened and velvety. Flakes of fibrin appear and

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

8

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

cause loops of intestine to become adherent to one another and to the

parietals. There is an outpouring of serous inflammatory exudates rich in

leucocytes and plasma proteins that soon becomes turbid; if localization

occurs, the turbid fluid becomes frank pus. Peristalsis is retarded in affected

bowel and this helps to prevent distribution of the infection. The greater

momentum, by enveloping and becoming adherent to inflamed structures,

often forms a substantial barrier to the spread of infection.

Surgical

Drains are frequently placed during operation to assist localization (and

exit) of intra-abdominal collections: their value is disputed. They may act as

conduits for exogenous infection.

Diffuse peritonitis

A number of factors may favour the development of diffuce peritonitis:

Speed of peritoneal contamination is a prime factor. If an inflamed

appendix . or other hollow viscus perforates before localization has

taken place, there is a gush of contents into the peritoneal cavity,

which may spread over a large area almost instantaneously.

Perforation proximal to an obstruction or from sudden anastomotic

separation is associated with severe generalised peritonitis and a high

mortality rate.

Stimulation of peristalsis by the ingestion of food or even water

hinders localisation. Violent peristalsis occasioned by the

administration of a purgative or an enema may cause the widespread

distribution of an infection that would otherwise have remained

localised.

The virulence of the infecting organism may be so great as to render

the localisation of infection difficult or impossible.

Young children have a small omentum, which is less effective in

localizing infection.

Disruption of localised collections may occur with injudicious

handling, e.g. appendix mass or pericolic abscess.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

9

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Deficient natural resistance (“immune deficiency “) may result from

use of drugs (e.g. steroids), disease { e.g. acquired immune deficiency

syndrome(ADIS)} or old age.

Clinical features

Localised peritonitis

Localised peritonitis is bound up intimately with the causative condition,

and the initial symptoms and signs are those of that condition. When the

peritoneum becomes inflamed, the temperature, and especially the pulse

rate, rise. Abdominal pain increase and usually there is associated vomiting.

The most important sign is guarding and rigidity of the abdominal wall over

the area of the abdomen that is involved, with a positive ”release” sign

(rebound tenderness). If inflammation arises under the diaphragm, shoulder

tip (“phernic”) pain may be felt. In cases of pelvic peritonitis arising from

an inflamed appendix in the pelvic position or from salpingitis, the

abdominal signs are often slight; there may be deep tenderness of one or

both lower quadrants alone, but a rectal or vaginal examination reveals

marked tenderness of the pelvic peritoneum. With appropriate treatment,

localised peritonitis usually resolves; in about 20% of cases, an abscess

follows. Infrequently, localised peritonitis becomes diffuse. Conversely, in

favourable circumstances, diffuse peritonitis can become localised, most

frequently in the pelvis or at multiple sites within the abdominal cavity.

Diffuse (generalised) peritonitis

Diffuse (generalised) peritonitis may present in differing ways dependent on

the duration of infection.

Early

Abdominal pain is severe and made worse by moving or breathing. It is first

experienced at the site of the original lesion and spreads outwards from this

point. Vomiting may occur. The patient usually lies still. Tenderness and

rigidity on palpation are found typically when the peritonitis affects the

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

10

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

anterior abdominal wall. Abdominal tenderness and rigidity are diminished

or absent if the anterior wall is unaffected, as in pelvic peritonitis or, rarely,

peritonitis in the lesser sac. Patients with pelvic peritonitis may complain of

urinary symptoms; they are tender on rectal or vaginal examination.

Infrequent bowel sounds may still be heard for a few hours but they cease

with the onset of paralytic ileus. The pluse rises progressively but, if the

peritoneum is deluged with irritant fluid, there is a sudden rise. The

temperature changes are variable and can be subnormal.

Late

If resolution or localisation of generalised peritonitis does not occur, the

abdomen remains silent and increasingly distends.

Circulatory failure ensues, with cold, clammy extremities, sunken eyes, dry

tongue, thread (irregular) pulse and drawn and anxious face (Hippocratic

fancies; The patient finally lapses into unconsciousness. With early

diagnosis and adequate treatment, this condition is rarely seen in modern

surgical practice.

Summary box .

Clinical features in peritonitis

o Abdominal pain, worse on movement.

o Guarding/rigidity of abdominal wall.

o Pain/tenderness on rectal/ vaginal examination (pelvic peritonitis).

o Pyrexia (may be absent).

o Raised pulse rate.

o Absent or reduced bowel sounds.

o

“Septic shock” {systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in later

stages.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

11

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Diagnostic aids

Investigations may elucidate a doubtful

diagnosis, but the importance of a careful

history and repeated examination must

not be forgotten.

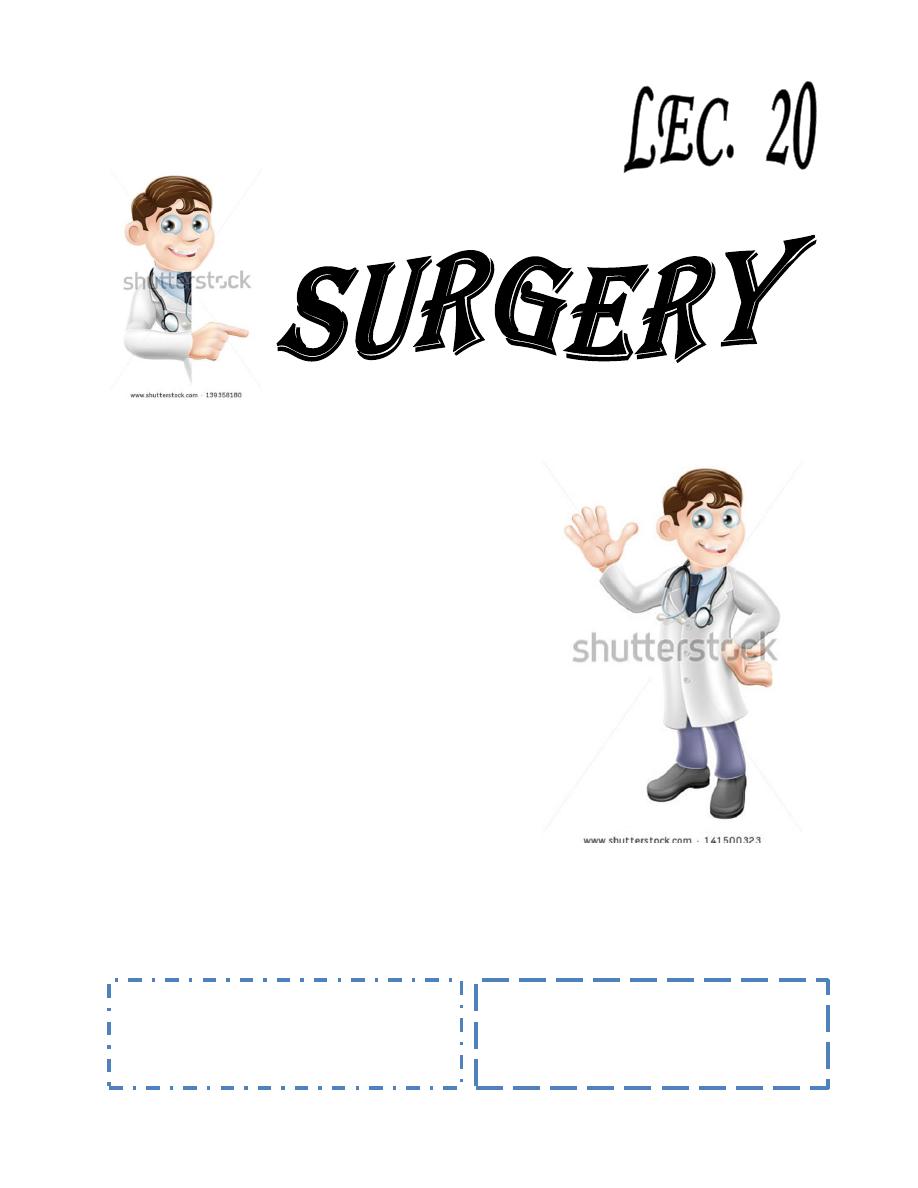

A radiograph of the abdomen may confirm

the presence of dilated gas-filled loops of

bowel ( consistent with a paralytic ileus)

or show free gas, although the latter is

best shown on an erect chest radiograph .

If the patient is too ill for an “erect” film

to demonstrate free air under the diaphragm, a lateral decubitus film is just

as useful, showing gas beneath the abdominal wall.

Serum amylase estimation may establish the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis

provided that it is remembered that moderately raised values are frequently

found following other abdominal catastrophes and operations, e.g.

perforated duodenal ulcer.

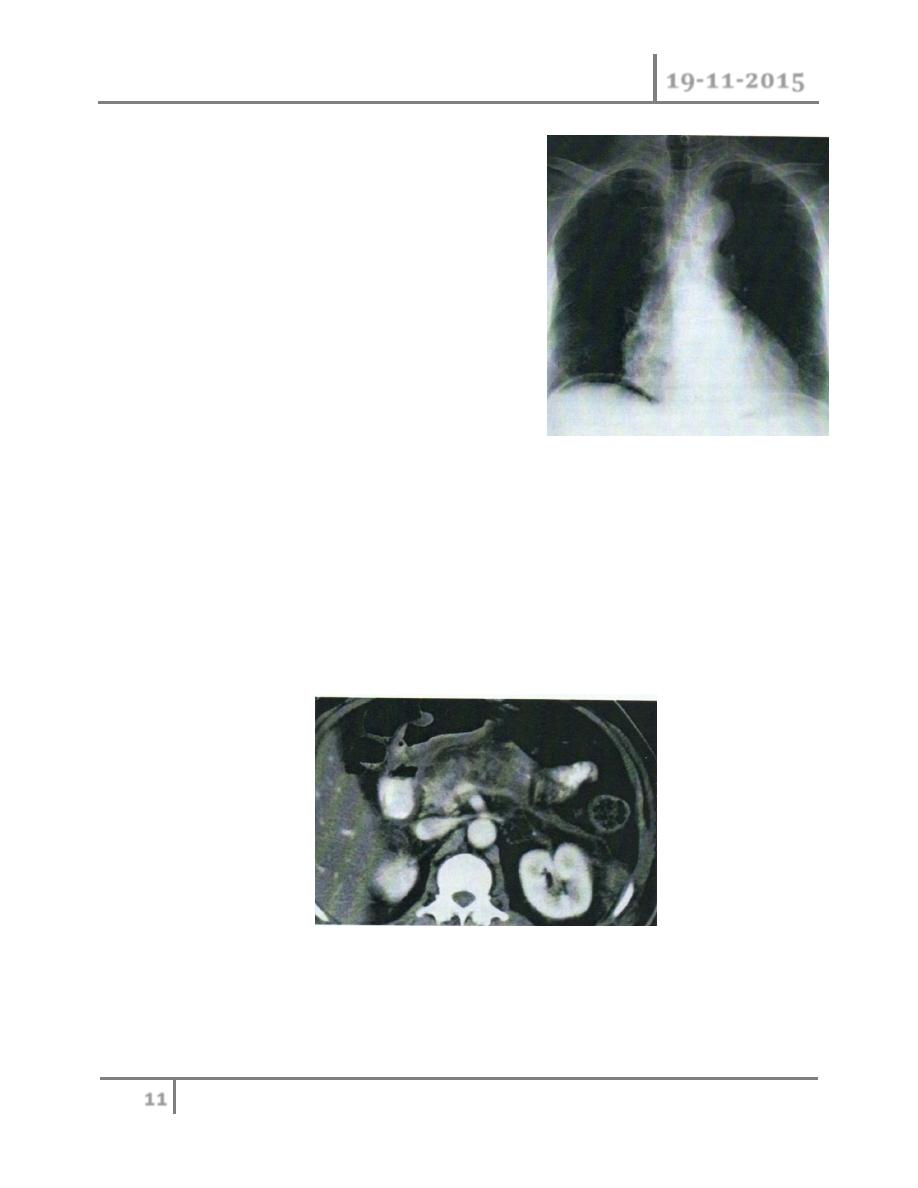

Ultrasound and computerized tomography (CT) scanning are increasingly

used to identify the cause of peritonitis Such knowledge may influence

management decisions

Peritoneal diagnostic aspiration may be helpful but is usually unnecessary.

Bile-stained fluid indicates a perforated peptic ulcer or gall bladder; the

presence of pus indicates bacterial peritonitis. Blood is aspirated in a high

proportion of patients with intraperitoneal bleeding.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

12

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Summary box.

Investigations in peritonitis

o Raised white cell count and C-reactive protein are usual.

o Serum amylase >4x normal indicates acute pancreatitis.

o Abdominal radiographs are occasionally helpful.

o Erect chest radiographs may show free peritoneal gas (perforated viscus).

o Ultrasound/CT scanning often diagnostic.

o Peritoneal fluid aspiration (with or without ultrasound guidance) may be

helpful.

Treatment

In case of doubt, early surgical intervention is to be preferred to a “wait and see”

policy. This rule is particularly true for previously healthy patients and those with

postoperative peritonitis. Caution is required in patients at high operative risk

because of co morbidity or advanced age.

Treatment consists of:

A- general care of the patient;

B- specific treatment of the cause;

C- peritoneal lavage when appropriate.

A-General care of the patient

1- Correction of circulating volume and electrolyte imbalance.

Patients are frequently hypovolaemic with electrolyte disturbances. The

plasma volume must be restored and electrolyte concentrations corrected.

Central venous catheterization and pressure monitoring may be helpful,

particularly in patients with concurrent disease. Plasma protein depletion

may also need correction as the inflamed peritoneum leaks large amounts of

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

13

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

protein. If the patient‟s recovery is delayed for more than 7-10 days,

intravenous nutrition is required.

2- Gastrointestinal decompression

A nasogastric tube is passed into the stomach and aspirated. Intermittent

aspiration is maintained until the parplytic ileus has resolved. Measured

volumes of water are allowed by mouth when only small amounts are being

aspirated. If the abdomen is soft and not tender, and bowel sounds return,

oral feeding may be progressively introduced. It is important not to prolong

the ileus by missing this stage.

3- Antibiotic therapy

Administration of antibiotics prevents the multiplication of bacteria and the

release of endotoxins. As the infection is usually a mixed one, initial

treatment with parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics active against aerobic

and anaerobic bacteria should be given.

4- Correction of fluid loss

A fluid balance chart must be started so that daily output by gastric

aspiration and urine is known. Additional losses from the lungs, skin and in

faces are estimated, so that the intake requirements can be calculated and

seen to have been administered. Throughout recovery, the haematocrit and

serum electrolytes and urea must be checked regularly.

5- Analgesia

The patient should be nursed in the sitting-up position and must be relieved

of pain before and after operation. If appropriate expertise is available,

epidural infusion may provide excellent analgesia. Freedom from pain

allows early mobilization and adequate physiotherapy in the postoperative

period, which help to prevent basal pulmonary collapse, deep vein

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

6- Vital system support

Special measures may be needed for cardiac, pulmonary and renal support,

especially if septic shock is present.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

14

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

B-Specific treatment of the cause

If the cause of peritonitis is amenable to surgery, operation must be carried

out as soon as the patient is fit for anaesthesia. This is usually within a few

hours. In peritonitis caused by pancreatitis or salpingitis, or in cases of

primary peritonitis of streptococcal or pneumococcal origin, non-operative

treatment is preferred provided the diagnosis can be made with confidence.

C-Peritoneal lavage

In operations for general peritonitis it is essential that, after the cause has

been dealt with, the whole peritoneal cavity is explored with the sucker and,

if necessary, mopped dry until all seropurulent exudates is removed. The use

of a large volume of saline (1-2 litters) containing dissolved antibiotic (e.g.

tetracycline) has been shown to be effective (Matheson) .

Summary box.

Management of peritonitis

o General care of patient:

Correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance.

Insertion of nasogastric drainage tube.

Broad – spectrum antibiotic therapy.

Analgesia.

Vital system support.

o Operative treatment of cause when appropriate with peritoneal

debridement/lavage.

Prognosis and complications

With modern treatment, diffuse peritonitis carries a mortality rate of about 10%.

The systemic and local complications are shown in Summary boxes.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

15

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Summary boxes .

Systemic complications of peritonitis

o Bacteraemic/endotoxic shock.

o Bronchopneumonia/ respiratory failure.

o Renal failure.

o Bone marrow suppression .

o Multisystem failure.

Summary boxes .

Abdominal complications of peritonitis

o Adhesional small bowel obstruction.

o Paralytic ileus.

o Residual or recurrent abscess.

o Portal pyaemia/liver abscess.

Acute intestinal abstruction due to peritoneal adhesions

The usually gives central colicky abdominal pain with evidence of small

bowel gas and fluid levels sometimes confined to the proximal intestine on

radiography. Bowel sounds are increased. It is more common with localised

peritonitis. It is essential to distinguish this from paralytic ileus.

Paralytic ileus

There is usually little pain, and gas-filled loops with fluid levels are seen

distributed throughout the small and large intestine on abdominal imaging. In

paralytic ileus, bowel sounds are reduced or absent.

Abdominal and pelvic abscesses

Abscess formation following local or diffuse peritonitis usually accupies one of the

situations shown in The symptoms and signs of a purulent collection may be vague

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

16

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

and consist of nothing more than lassitude, anorexia and malaise; pyrexia (often

low – grade), tachycardia, leucocytosis, raised C-reactive protein and localised

tenderness are also common

Summary box .

Clinical features of an abdominal/pelvic abscess

o Malaise

o Sweats with or without rigors.

o Abdominal/pelvic (with or without shoulders tip) pain.

o Anorexia and weight loss.

o Symptoms from local irritation, e.g. hiccoughs (subphrenic), diarrhea and

mucus (pelvic).

o Swinging pyrexia.

o Localised abdominal tenderness/mass.

Later, a palpable mass may develop that should be monitored by marking out its

limits on the abdominal wall and meticulous daily examination. More commonly,

its course is monitored by repeat ultrasound or CT scanning. In most cases, with

the aid of antibiotic treatment, the abscess or mass gradually reduces in size until,

finally, it is undetectable. In others, the abscess fails to resolve or becomes larger,

in which event it must be drained. In many situations, by waiting for a few days the

abscess becomes adherent to the abdominal wall, so that it can be drained without

opening the general peritoneal cavity. If facilities are available, ultrasound or CT

guided drainage may avoid further operation. Open drainage of an intraperitoneal

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

17

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

collection should be carried out by cautious blunt finger exploration to minimize

the risk of an intestinal fistula.

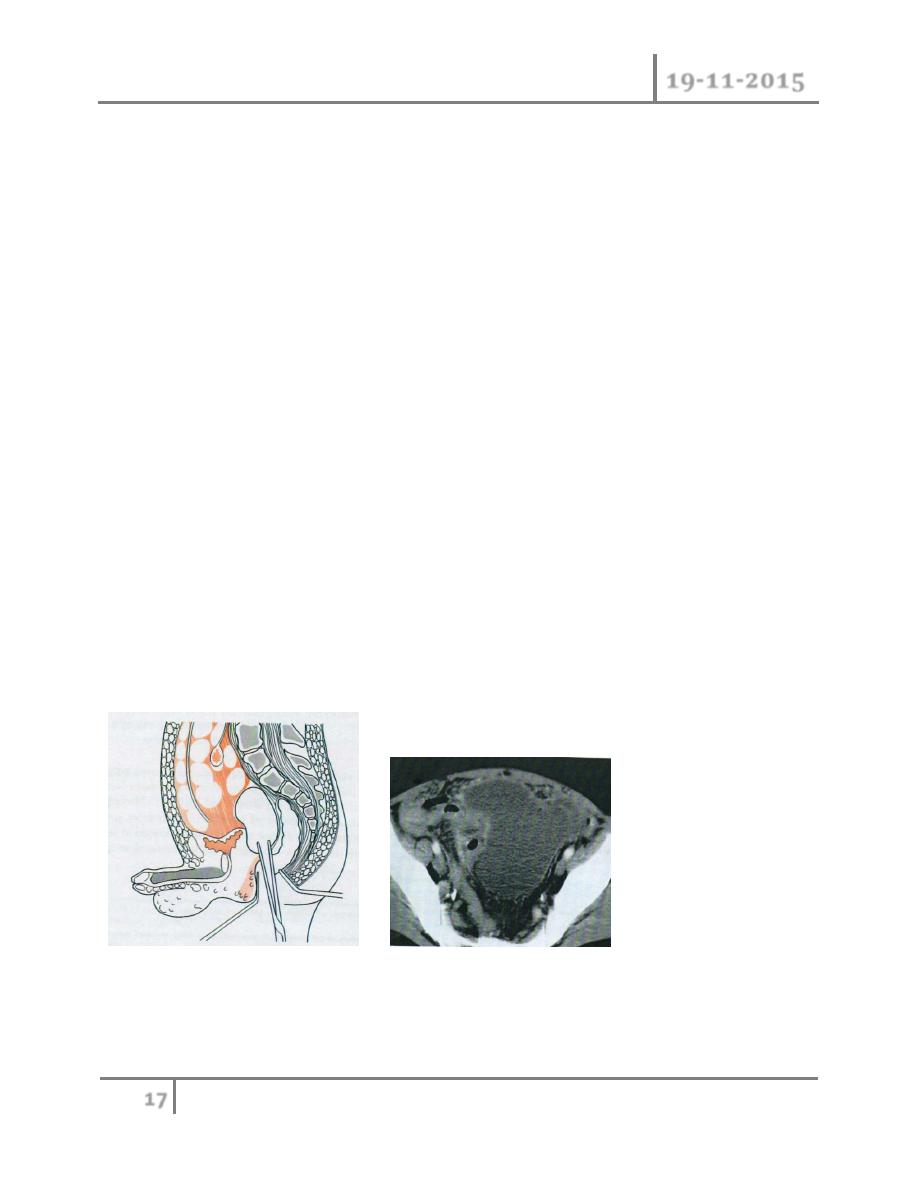

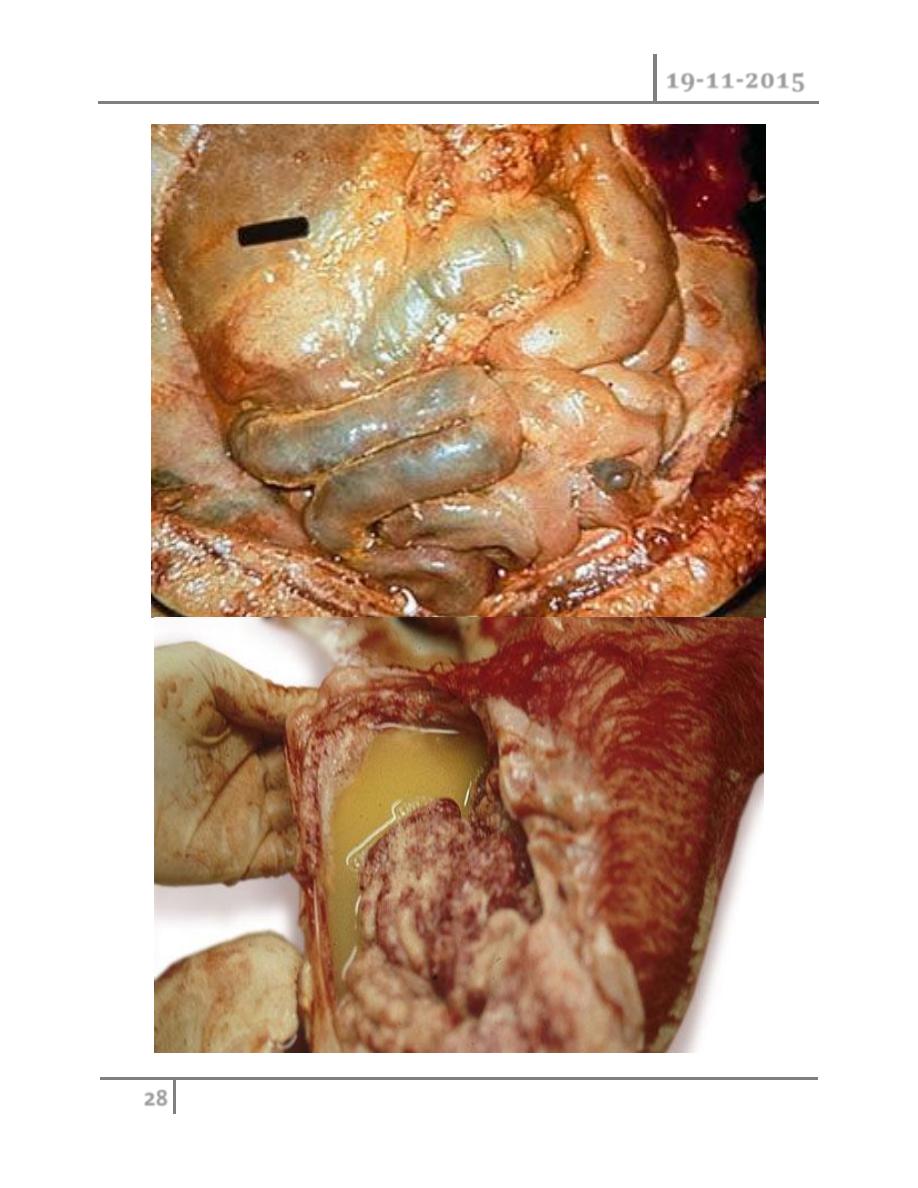

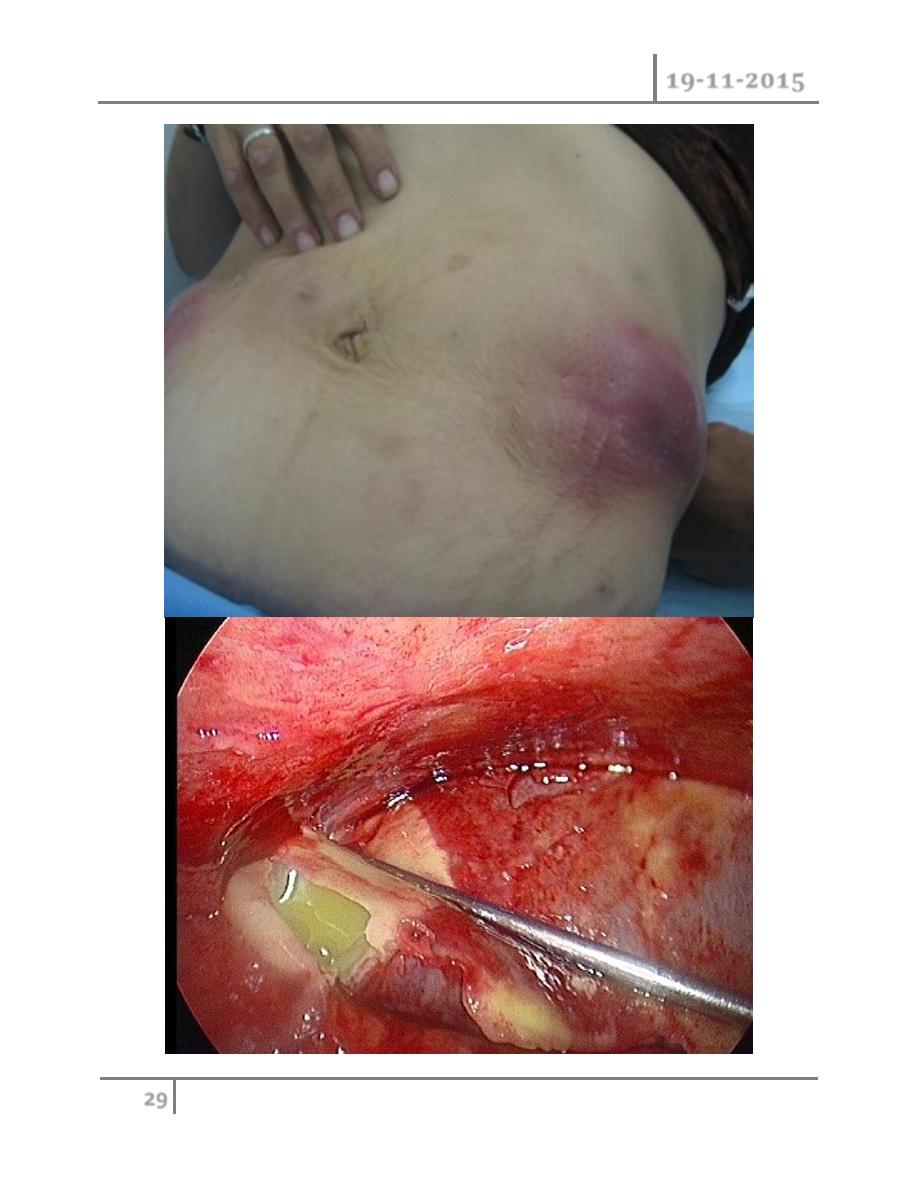

Pelvic abscess

The pelvis is the commonest site of an intraperitoneal abscess because the

vermiform appendix is often pelvic in position and the fallopian tubes are frequent

sites of infection. A pelvic abscess can also occur as a sequel to any case of diffuse

peritonitis and is common after anastomostic leakage following colorectal surgery.

The most characteristic symptoms are diarrhea and the passage of mucus in the

stools. Rectal examination reveals a bulging of the anterior rectal wall, which,

when the abscess is ripe, becomes softly cystic. Left to nature, a proportion of these

abscesses burst into the rectum, after which the patient nearly always recovers

rapidly. If this does not occur, the abscess is definitely pointing into the rectum,

rectal drainage (Fig. 58.6) is employed. If any uncertainty exists, the presence of

pus should be confirmed by ultrasound or CT scanning with needle aspiration if

indicated. Laparotomy is almost never necessary. Rectal drainage of a pelvic

abscess is far preferable to suprapubic drainage, which risks exposing the general

peritoneal cavity to infection. Drainage tubes can also be inserted percutaneously

or via the vagina or rectum under ultrasound or CT guidance .

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

18

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Intraperitoneal abscess

Anatomy

The complicated arrangement of the peritoneum results in the formation of four

intraperitoneal spaces in which pus may collect

Left subphrenic space

This is bound above by the diaphragm and behind by the left triangular ligament

and the left lobe of the liver, the gastrohepatic omentum and the anterior surface of

the stomach. To the right is the falciform ligament and to the left the spleen,

gastosplenic omentum and diaphragm. The common cause of an abscess here is an

operation on the stomach, the tail of the pancreas, the spleen or the splenic flexure

of the colon.

Left subhepatic space/lesser sac

The commonest cause of infection here is complicated acute pancreatitis. In

practice, a perforated gastric ulcer rarely causes a collection here because the

potential space is obliterated by adhesions.

Right subphrenic space

This space lies between the right lobe of the liver and the diaphragm. It is limited

posteriorly by the anterior layer of the coronary and the right triangular ligaments

and to the left by the falciform ligament. Common causes of abscess here are

perforating cholecystitis, a perforated duodenal ulcer, a duodenal cap “blow-out”

following gastrectomy and appendicitis.

Right subhepatic space

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

19

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

This lies transversely beneath the right lobe of the liver in Rutherford Morison‟s

pouch. It is bounded on the right by the right lobe of the liver and the diaphragm.

To the left is situated the foramen of Winslow and below this lies the duodenum. In

front are the liver and the gall bladder and behind are the upper part of the right

kidney and the diaphragm. The space is bounded above by the liver and below by

the transverse colon and hepatic flexure. It is the deepest space of the four and the

commonest site of a subphrenic abscess, which usually arises from appendicitis,

cholecystitis, a perforated duodenal ulcer or following upper abdominal surgery.

Clinical features

The symptoms and signs of subphrenic infection are frequently non-specific and it

is well to remember the aphorism, “pus somewhere, pus nowhere else, under the

diaphragm”.

Symptoms

A common history is that, when some infective focus in the abdominal cavity has

been dealt with, the condition of the patient improves temporarily but, after an

interval of a few days or weeks, symptoms of toxaemia reappear. The condition of

the patient steadily, and often rapidly, deteriorates. Sweating, wasting and

anorexia are present. There is sometimes epigastric fullness and pain, or pain in

the shoulder on the affected side, because of irritation of sensory fibres in the

phrenic nerve, referred along the descending branches of the cervical plexus.

Persistent hiccoughs may be a presenting symptom.

Signs

A swinging pyrexia is usually present. If the abscess is anterior, abdominal

examination will reveal some tenderness, rigidity or even a palpable swelling.

Sometimes the liver is displaced downwards but more often it is fixed by adhesions.

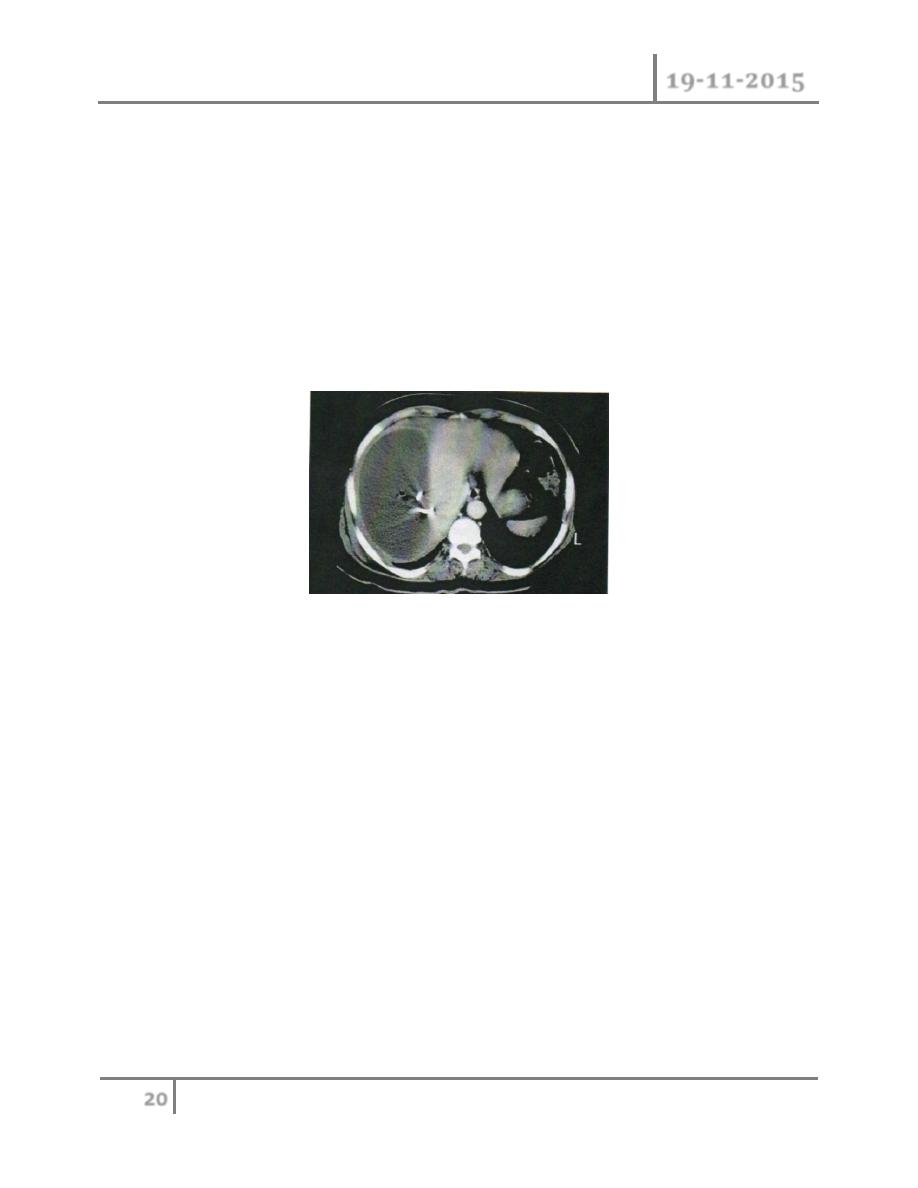

Examination of the chest is important and, in the majority of cases, collapse of the

lung or evidence of basal effusion or even an empyema is found.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

20

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Investigations

A number of the following investigations may be helpful:

o Blood tests usually show a leucocytosis and raised C-reactive protein.

o A plain radiograph sometimes demonstrates the presence of gas or a pleural

effusion. On screening, the diaphragm is often seen to be elevated (so called

“tented” diaphragm) and its movements impaired.

o Ultrasound or CT scanning is the investingation of choice and permits early

detection of subphrenic collections

o Radiolabelled white cell scanning may occasionally prove helpful when

other imaging techniques have failed.

Differential diagnosis

Pyelonephritis, amoebic abscess, pulmonary collapse and pleural empyema may

give rise to diagnostic difficulty.

Treatment

o The clinical course of suspected case is monitored, and blood tests and

imaging investigations are carried out at suitable intervals. If suppuration

seems probable, intervention is indicated. If skilled help is available it is

usually possible to insert a percutaneous drainage tube under ultrasound or

CT control. The same tube can be used to instill antibiotic solutions or

irrigate the abscess cavity. To pass an aspirating needle at the bedside

through the pleura and diaphragm invites potentially catastrophic spread of

the infection into the pleural cavity.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

21

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

o If an operative approach is necessary and a swelling can be detected in the

subcostal region or in the loin, an incision is made over the site of masimum

tenderness or over any area where oedema or reness is discovered. The

parietes usually form part of the abscess wall so that contamination of the

general peritoneal cavity is unlikely.

o If no swelling is apparent, the subphrenic spaces should be explored by

either an anterior subcostal approach or from behind after removal of the

outer part of the 12th rib according to the position of the abscess on

imaging. When the posterior approach, the pleura must not be opened and,

after the fibers of the diaphragm have been separated, a finger is inserted

beneath the diaphragm so as to explore the adjacent area. The aim with all

techniques of drainage is to avoid dissemination of pus into the peritoneal or

pleural cavities.

o When the cavity is reached, all of the fibrinous loculi must be broken down

with the finger and one or two drainage tubes must be fully inserted. These

drains are withdrawn gradually during the next 10 days and the closure of

the cavity is checked by sonograms or scanning. Appropriate antibiotics are

also given.

Special forms of peritonitis

Postoperative

o The patient is ill with raised pulse and peripheral circulatory failure.

Following an anastigmatic dehiscence, the general condition of a patient is

usually more serious than if the patient had suffered leakage from a

perforated peptic ulcer with no preceding operation. Local symptoms and

signs are less definite. Abdominal pain may not be prominent and is often

difficult to assess because of normal wound pain and postoperative

analgesia. The patient‟s deterioration may be attributed wrongly to

cardiopulmonary collapse, which is usually concomitant.

o Peritonitis follows abdominal operations more frequently than is realized.

The principles of treatment do not differ from those of peritonitis of other

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

22

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

origin. Antibiotic therapy alone is inadequate; no antibiotic can stay the

onslaught of bacterial peritonitis caused by leakage from a suture line,

which must be dealt with by operation.

In patients on treatment with steroids

Pain is frequently slight or absent. Physical signs similarly vague and misleading.

In children

The diagnosis can be more diffuclt, particularly in the preschool child. Physical

signs should be elicited by a gentle, patient and sympathetic approach.

In patients with dementia

Such patients can be fractious and unable to give a reliable history. Abdominal

tenderness is usually well localised, but guarding and rigidity are less marked

because the abdominal muscles are often thin and weak.

Bile peritonitis

Unless there is reason to suspect that the biliary tract was damaged during

operation, it is improbable that bile as a cause of peritonitis will be thought of

until the abdomen has been opened. The common causes of bile peritonitis are

shown in Summary box.

Summary box .

Causes of bile peritonitis

o Perforated cholecysitits.

o Post cholecystectomy:

Cystic duct stump leakage

Leakage from an accessory duct in the gall bladder bed Bile duct

injury

T-tube drain dislodgement (or tract rupture on removal)

o Following other operations/ procedures:

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

23

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Leaking duodenal stump post gastrectomy

Leaking biliary – enteric anastomosis

Leakage around percutaneous placed biliary drains

o Following liver trauma

Unless the bile has extravasated slowly and the collection becomes shut off from

the general peritoneal cavity, there are signs of diffuse peritonitis. After a few

hours a tinge of jaundice is not unusual. Laparotomy (or laparoscopy) should be

undertaken with evacuation of the bile and peritoneal lavage. The source of bile

leakage should be identified. A leaking gall bladder is excised or a cystic duct

ligated. An injury to the bile duct may simply be drained or alternatively intubated;

later, reconstructive operation is often required. Infected bile is more lethal than

sterile bile. A “blown” duodenal stump should be drained as it is too oedematous

to repair, but sometimes it can be covered by a jejunal patch. The patient is often

jaundiced from absorption of peritoneal bile, but the surgeon must ensure that the

abdomen is not closed until any obstruction to a major bile duct has been either

excluded or relieved. Bile leaks after cholecystectomy or liver trauma may be dealt

with by percutaneous (ultrasound – guided) drainage and endoscopic biliary

stenting to reduce bile duct pressure. The drain is removed when dry and the stent

at 4-6 weeks.

Meconium peritonitis

Pneumococcal peritonitis

Primary pneumococcal peritonitis may complicate nephritic syndrome or cirrhosis

in children. Otherwise healthy children, particularly girls between 3 and 9 years of

age, may also be affected, and it is likely that the route of infection is sometimes

via the vagina and fallopian tubes. At other times, and always in males, the

infection is blood-borne and secondary to respiratory tract or middle ear disease.

The prevalence of pneumococcal peritonitis has declined greatly and the condition

is now rare.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

24

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Clinical features

The onset is sudden and the earliest symptom is pain localised to the lower half of

the abdomen. The temperature is raised to 39 0 C or more and there is usually

frequent vomiting. After 24-48 hours, profuse diarrhoea is characteristic. There is

usually increased frequency of micturition. The last two symptoms are caused by

severe pelvic peritonitis. On examination, abdominal rigidity is usually bilateral

but is less than in most cases of acute appendicitis with peritonitis.

Differential diagnosis

A leucocytosis of 30 000µ 1-1 (30 X 109 1-1) or more with approximately 90%

polymorphs suggests pneumococcal peritonitis rather than appendicitis. Even so, it

is often impossible to exclude perforated appendicitis. The other condition that

can be difficult to differentiate from primary pneumococcal peritonitis in its early

stage is basal pneumonia. An unduly high respiratory rate and the absence of

abdominal rigidity are the most important signs supporting the diagnosis of

pneumonia, which is usually confirmed by a chest radiograph.

Treatment

o After starting antibiotic therapy and correcting dehydration and electrolyte

imbalance, early surgery is required unless spontaneous infection of pre-

existing ascites is strongly suspected, in which case a diagnostic peritoneal

tap is useful. Laparotomy or laparoscopy may be used. Should the exudates

be odourless and sticky, the diagnosis of pneumococcal peritonitis

practically certain, but it is essential to careful exploration to exclude other

pathology. Assuming that no other cause for the peritonitis is discovered,

some of the exudates is aspirated and sent to the laboratory for microscopy,

culture and sensitivity tests. Thorough peritoneal lavage is carried out and

the incision closed. Antibiotic and fluid replacement therapy are continued.

Nasogastric suction drainage is essential. Recovery is usual.

o Other organisms are known to cause some cases of primary pneumococcal

peritonitis, the peritoneal in children, including Haemophilus, other

streptococci and a few Gram – negative bacteria. Underlying pathology (

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

25

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

including an intravaginal foreign body in girls) must always be excluded

before primary peritonitis can be diagnosed with certainty.

Idiopathic streptococcal and staphylococcal peritonitis in adults

Idiopathic streptococcal and staphylococcal peritonitis in adults is fortunately

rare. In streptococcal peritonitis, the peritoneal exudates is odourless and thin,

contains some flecks of fibrin and may be blood- stained. In these circumstances

pus is removed by suction, the abdomen closed with drainage and non-operative

treatment of peritonitis performed. The use of intravaginal tampons has led to an

increased incidence of Staphylococcus aureus infections: these can be associated

with “toxic shock syndrome” and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

Familial Mediterranean Fever (periodic peritonitis)

o Familial Mediterranean fever (periodic peritonitis) is characterized by

abdominal pain and tenderness, mild pyrexia, polymorphonuclear

leucocytosis and, occasionally, pain in the thorax and joints. The duration of

an attack is 24-72 hours, when it is followed by complete remission, but

exacerbations recur at regular intervals. Most of the patients have

undergone appendicectomy in childhood. This disease, often familial, is

limited principally to Arab. Armenian and Jewish populations; other races

are occasionally affected. Mutations in the MEFV (Mediterranean fever)

gene appear to cause the disease. This gene produces a protein called pyrin,

which is expressed mostly in neutrophils but whose exact function is not

known.

o Usually, children are affected but it is not rare for the disease to make its

first appearance in early adult life, with cases in women outnumbering those

in men by two one. Exceptionally the disease becomes manifest in patients

over 40 years of age. At operation, which may be necessary to exclude other

cases but should be avoided if possible, the peritoneum – particularly in the

vicinity of the spleen the gall bladder- is inflamed. There is no evidence that

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

26

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

the interior of these organs is abnormal. Colchincine therapy is used during

attacks and to prevent recurrent attacks.

Starch peritonitis

Like talc, starch powder has found disfavor as a surgical glove lubricant. In a few

starch-sensitive

Tuberculous Peritonitis

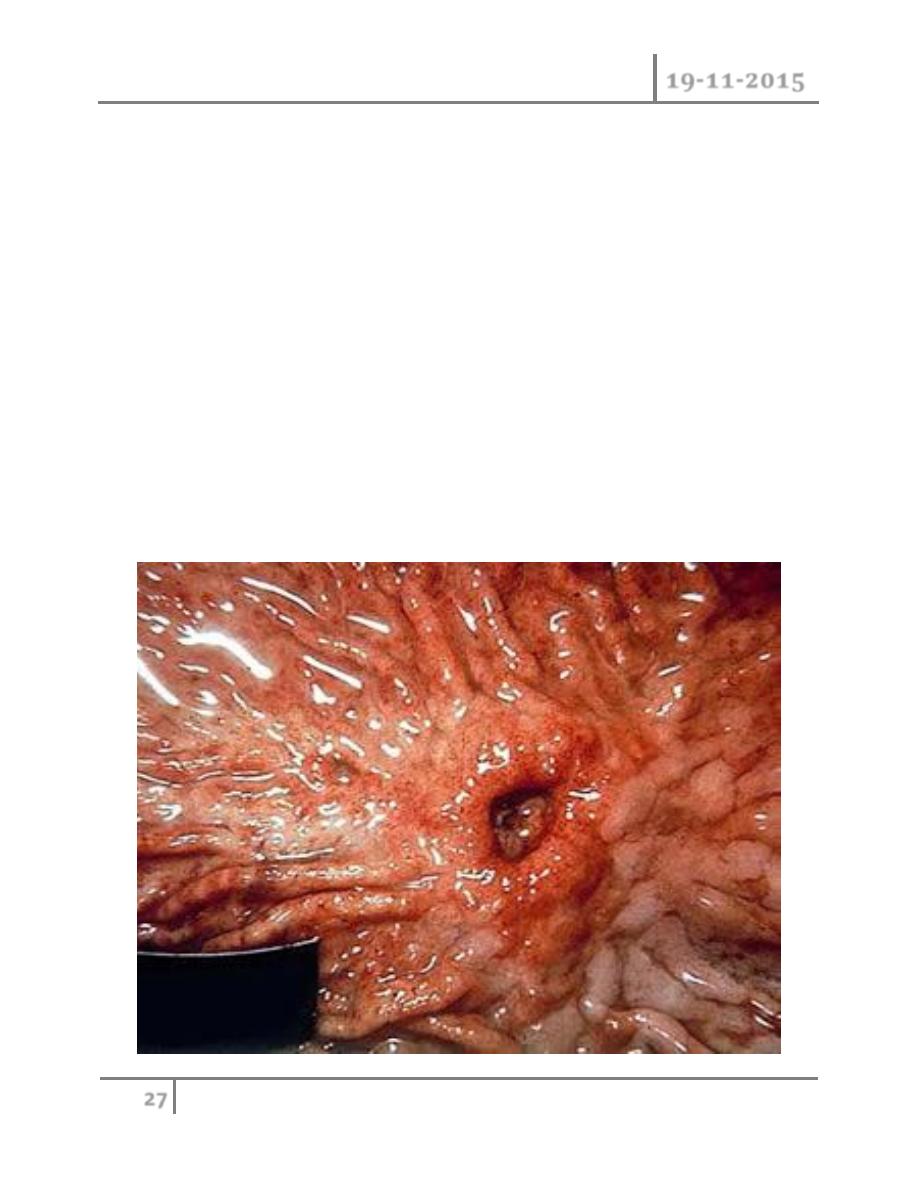

Acute tuberculous peritonitis

Tuberculous peritonitis sometimes has an onset that so closely resembles acute

peritonitis that the abdomen is opened. Straw-coloured fluid escapes and tubercles

are seen scattered over the peritoneum and greater omentum. Early tubercles are

grayish and translucent. They soon undergo caseation and appear white or yellow

and are then less difficult to distinguish from carcinoma. Occasionally, they

appear like patchy fat necrosis. On opening the abdomen and finding tuberculous

peritonitis, the fluid is evacuated, some being retained for bacteriological studies.

A portion of the diseased omentum is removed for histological confirmation of the

diagnosis and the wound closed without drainage.

Chronic tuberculous peritonitis

The condition presents with abdominal pain (90% of cases), fever (60%), loss of

weight (60%), ascites (60%), night sweats (37%) and abdominal mass (26%)

(Summary box).

Summary box .

Tuberculous peritonitis

o Acute and chronic forms.

o Abdominal pain, sweats, malaise and weight loss are frequent.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

27

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

o Caseating peritoneal nodules are common – distinguish from metastatic

carcinoma and fat necrosis of pancreatitis.

o Ascites common, may be loculated.

o Intestinal obstruction may respond to anti-tuberculous treatment without

surgery.

Origin of the infection

Infection originates from:

o tuberculous mesenteric lymph nodes;

o tuberculosis of the ileocaecal region;

o a tuberculous pyosalpinx;

o blood-borne infection from pulmonary tuberculosis, usually the “military”

but occasionally the “cavitating” form.

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

28

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016

Acute Peritonitis Dr. Basim Rassam

19-11-2015

29

©Ali Kareem 2015-2016