Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

Lec. 1

TUBERCULOSIS

Mon. 14 & 28 / 12 / 2015

Done By: Ibraheem Kais

2015 – 2016

ﻣﻜﺘﺐ ﺁ

ﺷﻮﺭ ﻟﻼﺳﺘﻨﺴﺎﺥ

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

1

Tuberculosis

Objectives

To recognize the characteristics and transmission of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis.

To describe the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis.

To determine factors increasing the risk of tuberculosis.

To judge the types and clinical features of tuberculosis.

To assess the chronic complications of pulmonary TB.

To define the characteristics of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

To assess the clinical and lab. methods to diagnose a case of TB.

To demonstrate the importance of Tuberculin skin test.

To illustrate drugs and methods of treatment of TB.

To recognize the problem of MDR and predisposing factors.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a serious global problem. It remains the number one killer

infectious disease in developing countries. The clinical manifestations of TB could be

either Pulmonary or Extra pulmonary (EPTB).

It is estimated that around one-third of the world's population has latent TB.

Characteristics of mycobacterium tuberculosis

Acid fast, intracellular parasites, have slow rates of growth, are obligate aerobes,

and in normal hosts induce a granulomatous response in tissue. Tuberculosis is caused

by any one of three mycobacterial pathogens that form part of the M. tuberculosis

complex: M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, and Mycobacterium africanum.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

2

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly one third (1.9

billion people) of all the people in the world are infected with M. tuberculosis.

The reasons for the resurgence of tuberculosis in the late 1980s and early 1990s

in the United States, as well as in Western Europe, are complex but revolve

largely around two major factors: the epidemic of infection with HIV and the

deterioration of public health systems.

TRANSMISSION OF MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS

Transmission of M. tuberculosis is influenced by features of the source case,

particularly the bacillary load, the closeness of the potential recipient of the

organism to the source, and the condition of the environmental air they share. A

possible additional factor is the infectivity of the organism: the degree to which

M. tuberculosis has the ability to establish itself within the lung or other sites in

the new host once transmission has occurred.

M. tuberculosis is spread by the inhalation of aerosolised droplet nuclei from

other infected patients.

Once inhaled, the organisms lodge in the alveoli and initiate the recruitment of

macrophages and lymphocytes. Macrophages undergo transformation into

epithelioid and Langhans cells which aggregate with the lymphocytes to form

the classical tuberculous granuloma.

Numerous granulomas aggregate to form a primary lesion or 'Ghon focus' (a

pale yellow, caseous nodule, usually a few mm to 1-2 cm in diameter), which is

characteristically situated in the periphery of the lung. Spread of organisms to

the hilar lymph nodes is followed by a similar pathological reaction; the

combination of a primary lesion and regional lymph nodes is referred to as the

'primary complex of Ranke‘ .

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

3

Reparative processes encase the primary complex in a fibrous capsule limiting

the spread of bacilli: so-called latent TB. If no further complications ensue, this

lesion eventually calcifies and is clearly seen on a chest X-ray. However,

lymphatic or haematogenous spread may occur before immunity is established,

seeding secondary foci in other organs including lymph nodes, serous

membranes, meninges, bones, liver, kidneys and lungs, which may lie dormant

for years.

The only clue that infection has occurred may be the appearance of a cell-

mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculin, demonstrated by

tuberculin skin testing.

If these reparative processes fail, primary progressive disease ensues .The

estimated lifetime risk of developing disease after primary infection is 10%, with

roughly half of this risk occurring in the first 2 years after infection

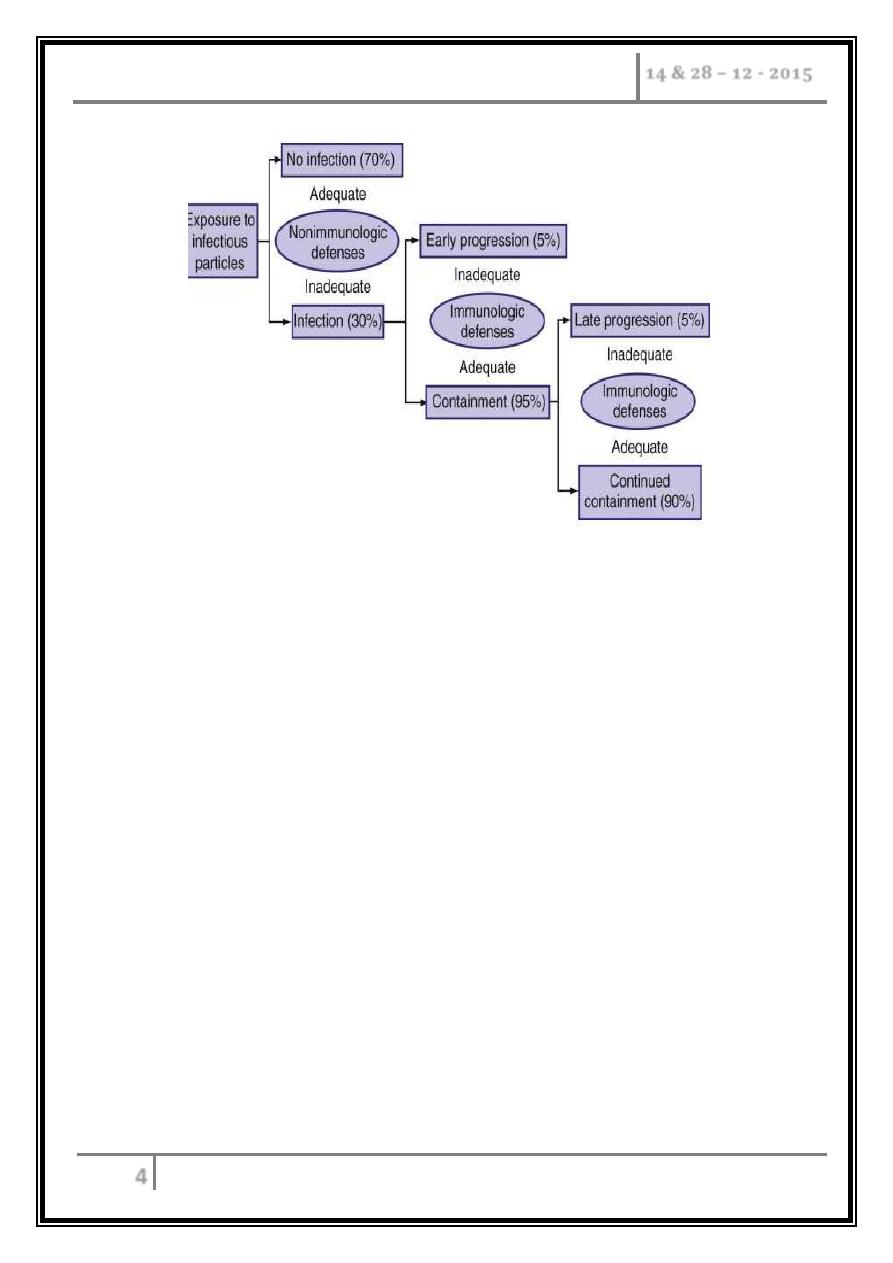

PATHOGENESIS

The genesis of the pathologic reactions in tuberculosis is linked with the response

of the host to the invading tubercle bacillus. In most individuals infected with M.

tuberculosis, the host response - both nonspecific and specific - restricts the growth of

the pathogen, thereby containing the infection. Paradoxically, however, a major

component of the tissue damage associated with tuberculosis is thought to result from

the immunologic responses to M. tuberculosis. The near absence of cell-mediated

immunity that occurs in patients with advanced HIV infection is assumed to be

responsible for the atypical presentations of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients.

Such patients tend not to have cavitary lung lesions and to have multisystem

involvement with tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

4

Factors increasing the risk of TB

Patient-related

- Age (children > young adults < elderly).

- First-generation immigrants from high-prevalence countries.

- Close contacts of patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB.

- Overcrowding.

- Chest radiographic evidence of self-healed TB.

- Primary infection < 1 year previously.

- Smoking.

Associated diseases

- Immunosuppression: HIV, anti-TNF therapy, high-dose corticosteroids,

cytotoxic agents.

- Malignancy (especially lymphoma and leukaemia).

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus.

- Chronic renal failure.

- Silicosis.

- Gastrointestinal disease associated with malnutrition (gastrectomy, jejuno-

ileal bypass, cancer of the pancreas, malabsorption).

- Deficiency of vitamin D or A.

- Recent measles: increases risk of child contracting TB.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

5

Clinical Features

Primary pulmonary TB

Primary TB refers to the infection of a previously uninfected (tuberculin-

negative) individual. A few patients develop a self-limiting febrile illness but

clinical disease only occurs if there is a hypersensitivity reaction or

progressive infection.

Progressive primary disease may appear during the course of the initial

illness or after a latent period of weeks or months.

Features of primary TB

o Infection (4-8 weeks).

o Influenza-like illness.

o Skin test conversion.

o Primary complex.

Disease

Lymphadenopathy: hilar

(often unilateral),

paratracheal or mediastinal.

Collapse (especially right

middle lobe).

Consolidation (especially

right middle lobe).

Obstructive emphysema.

Cavitation (rare).

Pleural effusion.

Endobronchial.

Miliary.

Meningitis.

Pericarditis.

Hypersensitivity

Erythema nodosum.

Phlyctenular conjunctivitis.

Dactylitis.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

6

Post-primary pulmonary TB

Post-primary disease refers to exogenous ('new' infection) or endogenous

(reactivation of a dormant primary lesion) infection in a person who has

been sensitised by earlier exposure.

It is most frequently pulmonary and characteristically occurs in the apex of

an upper lobe where the oxygen tension favours survival of the strictly

aerobic organism.

The onset is usually insidious, developing slowly over several weeks.

Systemic symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, loss of appetite and

weight, and are accompanied by progressive pulmonary symptoms

Radiological changes include ill-defined opacification in one or both of the

upper lobes, and as progression occurs, consolidation, collapse and

cavitation develop to varying degrees.

It is often difficult to distinguish active from quiescent disease on

radiological criteria alone, but the presence of a miliary pattern or

cavitation favours active disease.

In extensive disease, collapse may be marked and result in significant

displacement of the trachea and mediastinum.

Occasionally, a caseous lymph node may drain into an adjoining bronchus

resulting in tuberculous pneumonia

Clinical presentations of pulmonary TB

Chronic cough, often with haemoptysis.

Pyrexia of unknown origin.

Unresolved pneumonia.

Exudative pleural effusion.

Asymptomatic (diagnosis on chest X-ray).

Weight loss, general debility.

Spontaneous pneumothorax.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

7

Miliary TB

Blood-borne dissemination gives rise to miliary TB, which may present acutely

but more frequently is characterised by 2-3 weeks of fever, night sweats,

anorexia, weight loss and a dry cough. Hepatosplenomegaly may develop and

the presence of a headache may indicate coexistent tuberculous meningitis.

Auscultation of the chest is frequently normal, although with more advanced

disease widespread crackles are evident. Fundoscopy may show choroidal

tubercles. The classical appearances on chest X-ray are of fine 1-2 mm lesions

('millet seed') distributed throughout the lung fields, although occasionally the

appearances are coarser. Anaemia and leucopenia reflect bone marrow

involvement.

The TST may be negative in up to half of case but reactivity may be restored

during chemotherapy. Broncho-alveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy are

more likely to provide bacteriologic confirmation, and granulomas are evident

in liver or bone-marrow biopsy specimens from many patients. If it goes

unrecognized, miliary TB is lethal; with proper early treatment, however, it is

amenable to cure.

Glucocorticoid therapy has not proved beneficial.

'Cryptic' miliary TB is an unusual presentation sometimes seen in old age, it has

a chronic course characterized by mild intermittent fever, anemia, and

ultimately- meningeal involvement preceding death.

An acute septicemic form nonreactive miliary TB occurs very rarely and is due

to massive hematogenous dissemination of tubercle bacilli. Pancytopenia is

common in this form of disease, which is rapidly fatal. At postmortem

examination, multiple necrotic but non-granulomatous "non-reactive" lesions

are detected.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

8

Chronic complications of pulmonary TB

Pulmonary

- Massive haemoptysis.

- Cor pulmonale.

- Fibrosis/ emphysema.

- Atypical mycobacterial infection.

- Aspergilloma.

- Lung/ pleural calcification.

- Obstructive airways disease.

- Bronchiectasis.

- Bronchopleural fistula.

Non-pulmonary

- Empyema necessitans.

- Laryngitis.

- Enteritis.

- Anorectal disease.

- Amyloidosis.

- Poncet's polyarthritis.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

9

Extrapulmonary TB

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis presents more of a diagnostic and therapeutic

problem than does pulmonary tuberculosis.

In part, this relates to its being less common and therefore less familiar to most

clinicians and microscopy with the auramine or Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain is

frequently negative in cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis

In addition, extrapulmonary tuberculosis involves relatively inaccessible sites,

and often, because of the vulnerability of the areas involved, much greater

damage can be caused by fewer bacilli.

The combination of small numbers of bacilli in inaccessible sites causes

bacteriologic confirmation of a diagnosis to be more difficult, and invasive

procedures are frequently necessary to establish a diagnosis.

In addition to the need for invasive diagnostic procedures, surgery may be an

important component of management.

In 2007 in the United States, 20% of newly reported cases of tuberculosis

involved extrapulmonary sites only.

In order of frequency, the extrapulmonary sites most commonly involved in TB

are the lymph nodes, pleura, genitourinary tract, bones and joints, meninges,

peritoneum, and pericardium. However, virtually all organ systems may be

affected.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

10

Diagnosis of pulmonary TB

o Unexplained cough for more than 2-3 weeks.

o Typical chest X-ray changes.

o Direct microscopy of sputum is the most important first step.

o A positive smear is sufficient for the presumptive diagnosis of TB but definitive

diagnosis requires culture.

o Smear-negative sputum should also be cultured, as only 10-100 viable

organisms are required for sputum to be culture-positive. A diagnosis of smear-

negative TB may be made in advance of culture if the chest X-ray appearances

are typical of TB and there is no response to a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

o Specimens required:

Pulmonary:

- Sputum* (induced with nebulised hypertonic saline if not

expectorating).

- Bronchoscopy with washings or BAL.

- Gastric washing* (mainly used for children).

Extrapulmonary:

- Fluid examination (cerebrospinal, ascitic, pleural, pericardial,

joint) - yield classically is very low.

- Tissue biopsy (from affected site); also bone marrow/ liver may be

diagnostic in patients with disseminated disease.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

11

Diagnostic tests

Circumstantial (ESR, CRP, anaemia, etc.).

Tuberculin skin test (low sensitivity/specificity; useful only in primary or deep-

seated infection).

Stain:

- Ziehl-Neelsen.

- Auramine fluorescence.

Nucleic acid amplification.

Culture:

- Solid media (Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook).

- Liquid media (e.g. BACTEC).

Response to empirical antituberculous drugs (usually seen after 5-10 days).

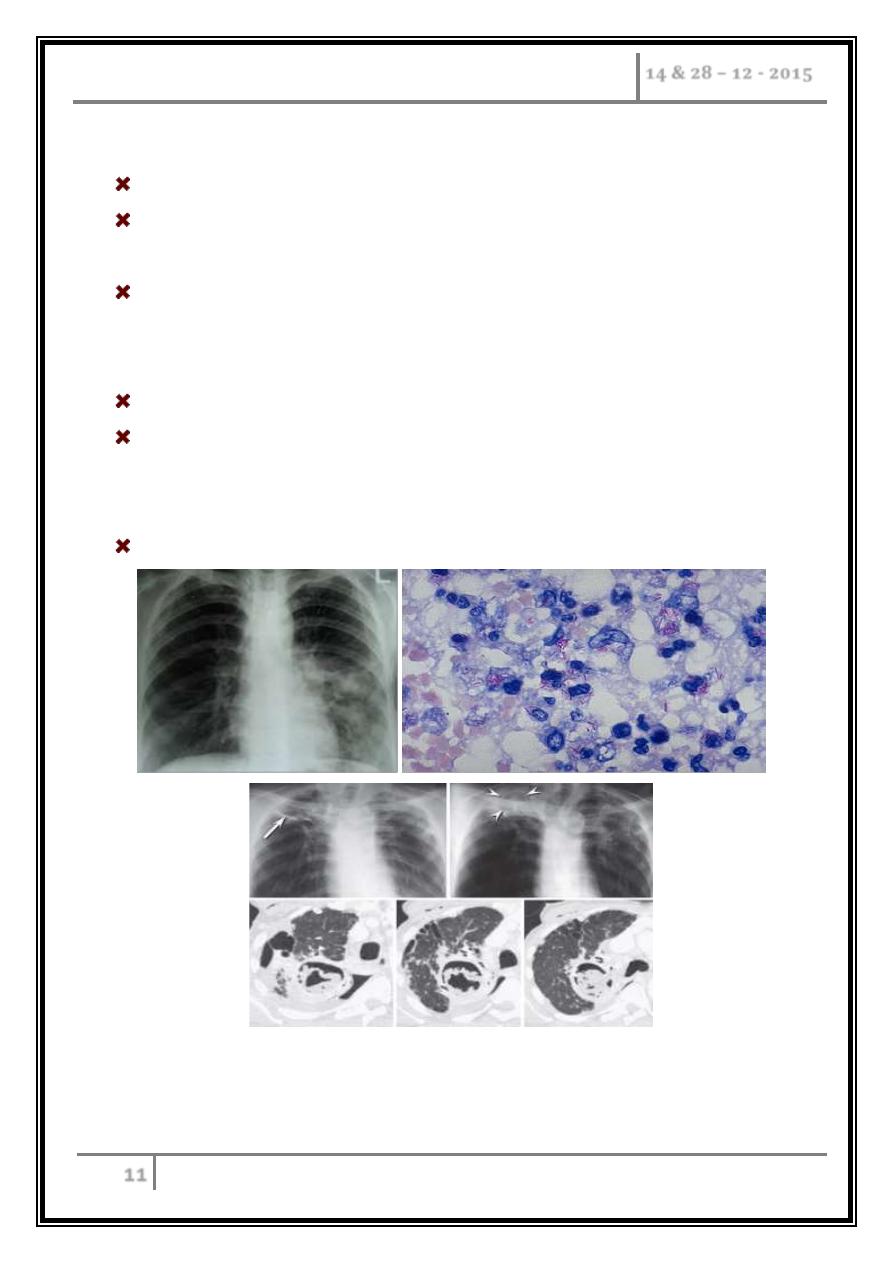

Aspergilloma developing in an old tuberculosis cavity. A, Front chest radiograph in a patient with

tuberculosis shows bilateral upper lobe fibronodular changes with a right apical cavity (arrow). B,

Frontal chest radiograph several years after (A) when the patient complained of hemoptysis shows

development of an opacity within the right apical cavity (arrowheads) representing aspergilloma. C-

E, Focused axial chest CT confirms the presence of aspergilloma.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

12

Tuberculin Skin Testing

Skin testing with tuberculin-PPD (tuberculin purified protein derivative) (TST)

is most widely used in screening for latent M. tuberculosis infection.

The test is of limited value in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis because of its

relatively low sensitivity and specificity and its inability to discriminate between

latent infection and active disease.

False-negative reactions are common in immunosuppressed patients and in

those with overwhelming tuberculosis.

False-positive reactions may be caused by infections with non-tuberculous

mycobacteria and by bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination.

The standard intermediate tuberculin test consists of the intracutaneous

injection (Mantoux's method) of 0.1 mL of material, which contains 0.0001 mg

of PPD purified protein derivative (5 TU). The site usually chosen is the volar

surface of the forearm, but any accessible area can be used. Conventionally, the

reading is done 48 to 72 hours after the injection, but it may be delayed for up

to 1 week.

The reaction size is determined by measuring the diameter of any induration

with a ruler. The amount of erythema should not be taken into account; only the

extent of induration is important. Readings must be recorded accurately in

millimeters. Thus, under most circumstances, a reading of 10 mm or more is

considered indicative of infection with M. tuberculosis. However, in some

situations, smaller reactions should be taken to indicate tuberculous infection.

For example, a reaction of 5 mm in a child who is a contact of a person with

smear-positive tuberculosis would probably indicate tuberculous infection and

be considered positive. Likewise, a 5-mm reaction in a person with known HIV

infection should be considered positive. There are several reasons why the

tuberculin reaction may be interpreted as negative in the presence of

tuberculous infection.

Two INF-γ release assays are currently approved for marketing.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

13

Treatment

The two aims of tuberculosis treatment are to interrupt tuberculosis transmission

by rendering patients noninfectious and to prevent morbidity and death by curing

patients with tuberculosis.

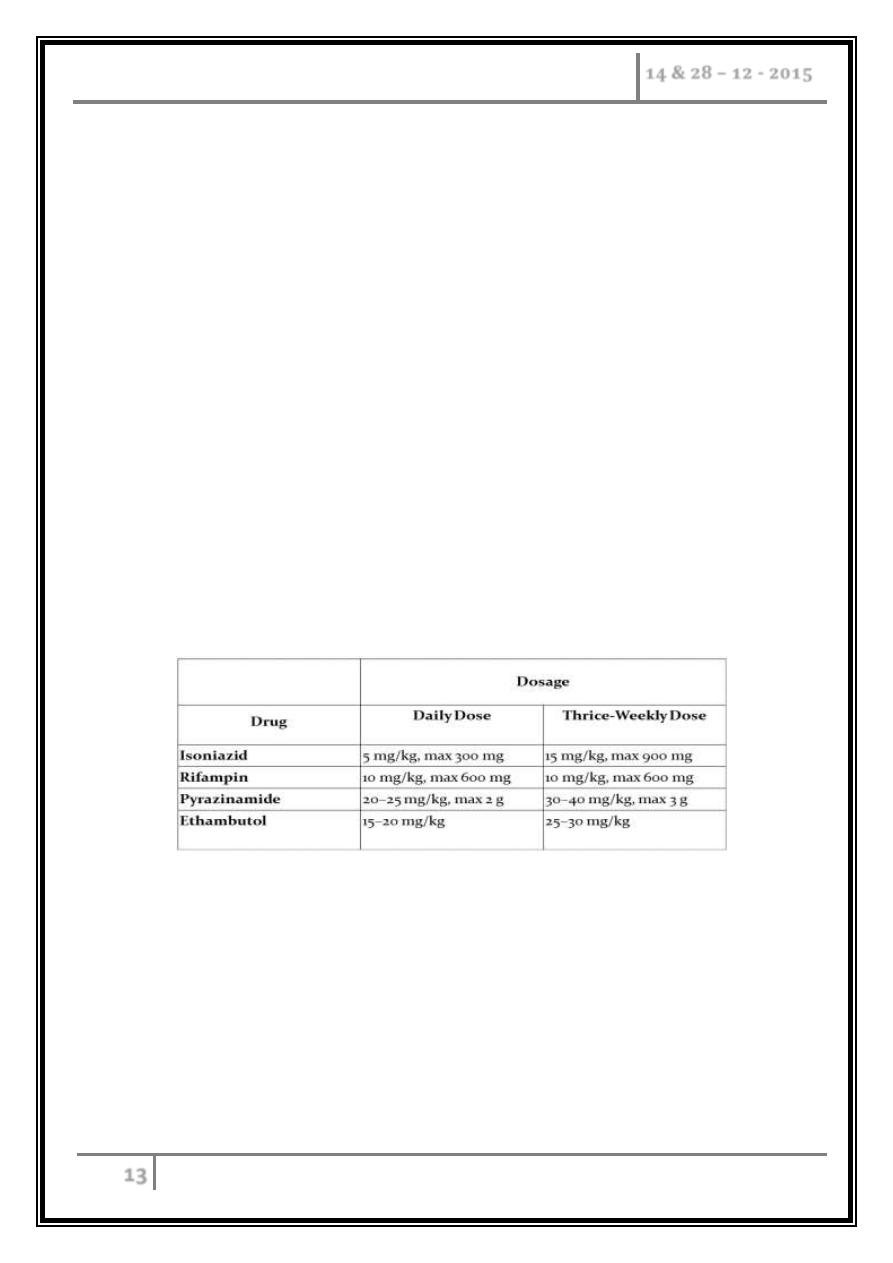

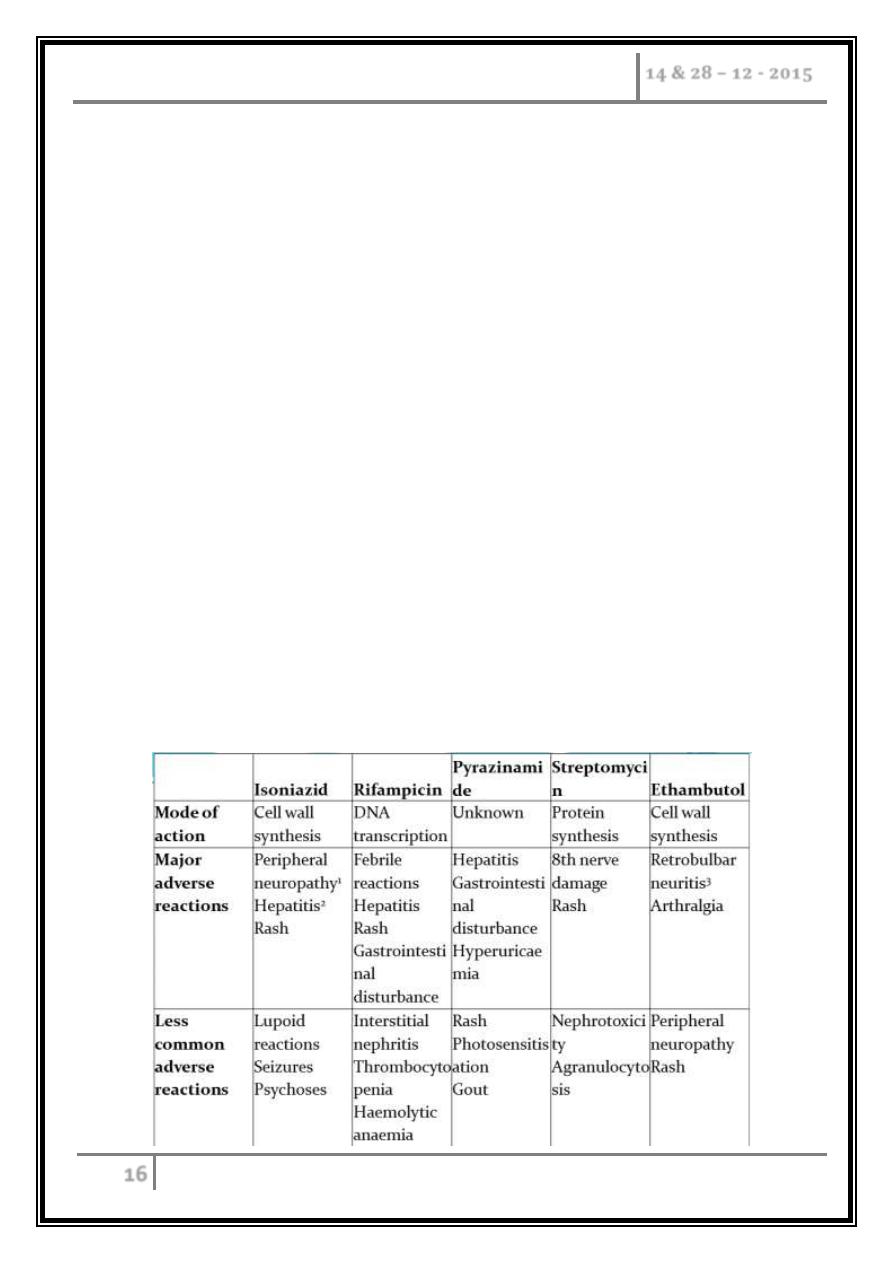

Drugs

Four major drugs are considered the first-line agents for the treatment of

tuberculosis: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. These drugs

are well absorbed after oral administration, with peak serum levels at 2–4 h

and nearly complete elimination within 24 h. These agents are recommended

on the basis of their bactericidal activity (i.e., their ability to rapidly reduce

the number of viable organisms and render patients non-infectious), their

sterilizing activity (i.e., their ability to kill all bacilli and thus sterilize the

affected tissues, measured in terms of the ability to prevent relapses), and

their low rate of induction of drug resistance.

Because of a lower degree of efficacy and a higher degree of intolerability

and toxicity, six classes of second-line drugs are generally used only for the

treatment of patients with tuberculosis resistant to first-line drugs.

Included in this group are the injectable aminoglycosides streptomycin

(formerly a first-line agent), kanamycin, and amikacin; the injectable

polypeptide capreomycin; the oral agents ethionamide, cycloserine, and PAS;

and the fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Of the quinolones, third-generation

agents are preferred: levofloxacin.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

14

Regimens

Standard short-course regimens are divided into an initial, or bactericidal,

phase and a continuation, or sterilizing, phase.

During the initial phase, the majority of the tubercle bacilli are killed,

symptoms resolve, and usually the patient becomes non-infectious.

The continuation phase is required to eliminate persisting mycobacteria and

prevent relapse.

The treatment regimen of choice for virtually all forms of tuberculosis in both

adults and children consists of a 2-month initial phase of isoniazid, rifampin,

pyrazinamide, and ethambutol followed by a 4-month continuation phase of

isoniazid and rifampin.

Treatment may be given daily throughout the course or intermittently (either

three times weekly throughout the course or twice weekly after an initial

phase of daily therapy, although the twice-weekly option is not recommended

by the WHO). Intermittent treatment is especially useful for patients whose

therapy is being directly observed.

Patients with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis and delayed sputum-culture

conversion (i.e., those who remain culture-positive at 2 months) should have

the continuation phase extended by 3 months, for a total course of 9 months.

To prevent isoniazid-related neuropathy, pyridoxine (10–25 mg/d) should be

added to the regimen given to persons at high risk of vitamin B6 deficiency.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

15

Monitoring treatment response and drug toxicity

Bacteriologic evaluation is the preferred method of monitoring the response

to treatment for tuberculosis. Patients with pulmonary disease should have

their sputum examined monthly until cultures become negative.

With the recommended regimen, >80% of patients will have negative sputum

cultures at the end of the second month of treatment. By the end of the third

month, virtually all patients should be culture-negative.

Patients with cavitary disease who do not achieve sputum culture conversion

by 2 months require extended treatment. When a patient's sputum cultures

remain positive at 3 months, treatment failure and drug resistance or poor

adherence with the regimen should be suspected.

A sputum specimen should be collected by the end of treatment to document

cure.

Monitoring of the response to treatment during chemotherapy by serial chest

radiographs is not recommended, as radiographic changes may lag behind

bacteriologic response and are not highly sensitive.

After the completion of treatment, neither sputum examination nor chest

radiography is recommended for routine follow-up purposes.

However, a chest radiograph obtained at the end of treatment may be useful

for comparative purposes should the patient develop symptoms of recurrent

tuberculosis months or years later.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

16

Drug toxicity

o Hepatitis: common, baseline assessment of liver function.

o Up to 20% of patients have small increases in aspartate aminotransferase (up

to three times the upper limit of normal) that are not accompanied by

symptoms and are of no consequence.

o For patients with symptomatic hepatitis and those with marked (five to six-

fold) elevations in serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, treatment

should be stopped and drugs reintroduced one at a time after liver function

has returned to normal.

o Hypersensitivity reactions usually require the discontinuation of all drugs

and rechallenge to determine which agent is the culprit.

o Hyperuricemia and arthralgia caused by pyrazinamide should be stopped if

the patient develops gouty arthritis.

o Individuals who develop autoimmune thrombocytopenia secondary to

rifampin therapy should not receive the drug thereafter. Similarly, the

occurrence of optic neuritis with ethambutol is an indication for permanent

discontinuation of this drug.

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

17

Drug-resistant TB

Drug-resistant TB is defined by the presence of resistance to any first-line

agent.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB is defined by resistance to at least rifampicin

and isoniazid, with or without other drug resistance.

Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB is defined by resistance to at least

rifampicin and isoniazid, in addition to any quinolone and at least one

injectable second-line agent.

The prevalence of MDR-TB is rising.

It is more common in those with a prior history of TB, particularly if

treatment has been inadequate, and those with HIV infection.

Diagnosis is challenging, especially in developing countries, and although

cure may be possible, it requires prolonged treatment with less effective,

more toxic and more expensive therapies.

Mortality rate from MDR-TB is high and that from XDR-TB higher still.

Factors contributing to emergence of drug-resistant TB

Drug shortages.

Poor-quality drugs.

Lack of appropriate supervision.

Transmission of drug-resistant strains.

Prior anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Treatment failure (smear-positive at 5 months).

Tuberculosis Dr. Abdulla Al- Farttoosi

14 & 28 – 12 - 2015

18

Vaccines

BCG (the Calmette-Guérin bacillus), a live attenuated vaccine derived from M.

bovis, is the most established TB vaccine. It is administered by intradermal injection

and is highly immunogenic. BCG appears to be effective in preventing disseminated

disease, including tuberculous meningitis, in children, but its efficacy in adults is

inconsistent and new vaccines are urgently needed. Current vaccination policies

usually target children and other high-risk individuals. BCG is very safe with the

occasional complication of local abscess formation. It should not be administered to

those who are immunocompromised (e.g. by HIV) or pregnant.

... End …