part III

OBJECTIVES:

By the end of these series of lecture on respiratory system pathology the students

would be able to:

1- define the pathogenesis and the pathological features of the most common tumor

like and tumor (benign and malignant) conditions of the upper respiratory tract

including: allergic nasal polyp, angiofibroma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, laryngeal

tumors including: vocal cord nodule, laryngeal papilloma and laryngeal carcinoma.

2- describe atelectasis of the lung and its classification.

3- define adult respiratory distress syndrome and its causes and pathological features.

4- define (the pathogenesis and the pathological features) and list obstructive

pulmonary disease: asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis and broncheactasis.

5- describe the pathogenesis, types and pathological features of diffuse interstitial

lung diseases.

6- define and list the granulomatous lung diseases.

7- identify the pathogenesis and pathological features of pulmonary infections.

8- outline the pathogenesis and the pathological features of pulmonary tuberculosis.

9- list and classify the most important lung tumors describing the pathogenesis and

pathological features, with clinical presentations including paraneoplastic syndrome

descriptions.

10- define diseases of the pluera and list the most common neoplasms of the pleura.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is by far the most important of the chronic penumonia; it causes 6%

of all deaths worldwide. Tuberculosis is

"a communicable chronic granulomatous

disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis".

It usually involves the lungs but

may affect any organ or tissue. Tuberculosis thrives wherever there is poverty,

crowding, and chronic debilitating illness; elderly, with their weakened defenses,

are also susceptible.

Certain disease states also increase the risk:

1. Diabetes mellitus

2. Hodgkin lymphoma

3. Chronic lung disease (particularly silicosis)

4. Chronic renal failure

5. Malnutrition & Alcoholism

6. Immunosuppression including HIV infection.

Most of these predisposing conditions are related to

impairment of T cell-mediated immunity against the

Mycobacteria.

The latter are slender rods that are acid fast, thus stained

positively with ZN stain. M. tuberculosis hominis is responsible

for most cases of tuberculosis.

Oropharyngeal and intestinal tuberculosis contracted by

drinking milk contaminated with Mycobacterium bovis is now

rare in developed nations.

Other mycobacteria, particularly

M. avium-intracellulare,

are

much less virulent than M. tuberculosis and rarely cause

disease. However, it

complicates up to 30% of patients with

AIDS.

Pathogenesis

Primary TB

In the previously unexposed immunocompetent individual

, the source of the

organism is

exogenous

; this leads to the development of cell mediated

immunity; primarily mediated by

T

H

1 cells,

which stimulate macrophages to

kill bacteria but this is associated simultaneously with the development of

destructive tissue hypersensitivity in the form of caseation necrosis.

The virulent organisms once inside macrophages impair effective

phagolysosomal digestion, which in turn leads to

unrestricted mycobacterial

proliferation

. Thus, the

earliest phase of primary tuberculosis is characterized

by bacillary proliferation within alveolar macrophages, with resulting

bacteremia and seeding of multiple sites

.

Nevertheless, most persons at this

stage are asymptomatic; only about 5% of the infected develop significant

disease.

The activated macrophages release a variety of mediators including secretion

of

TNF

, which is responsible for recruitment of monocytes, which in turn

undergo activation and differentiation into the

"epithelioid histiocytes" that

characterize the granulomatous response.

About

3 weeks

are needed for the development of the

hypersensitivity reaction

.

Pathological features of primary TB

The inhaled bacilli are embedded in the distal airspaces of the lower part of

the upper lobe or the upper part of the lower lobe, usually close to the pleura.

As sensitization develops, a

bout1 cm area of gray-white inflammatory

consolidation develops (the Ghon focus). The center of this focus undergoes

caseous necrosis.

Tubercle bacilli, either free or within phagocytes, drain to the regional nodes,

which also often caseate.

This combination of Ghon focus and nodal

involvement is referred to as the Ghon complex

.

During the first few weeks, there is also lymphatic and hematogenous

dissemination to other parts of the body.

In approximately

95%

of cases, development of cell-mediated immunity

controls the infection. Hence,

the Ghon complex undergoes progressive

fibrosis, often followed by radiologically detectable calcification, and, despite

seeding of other organs, no lesions develop.

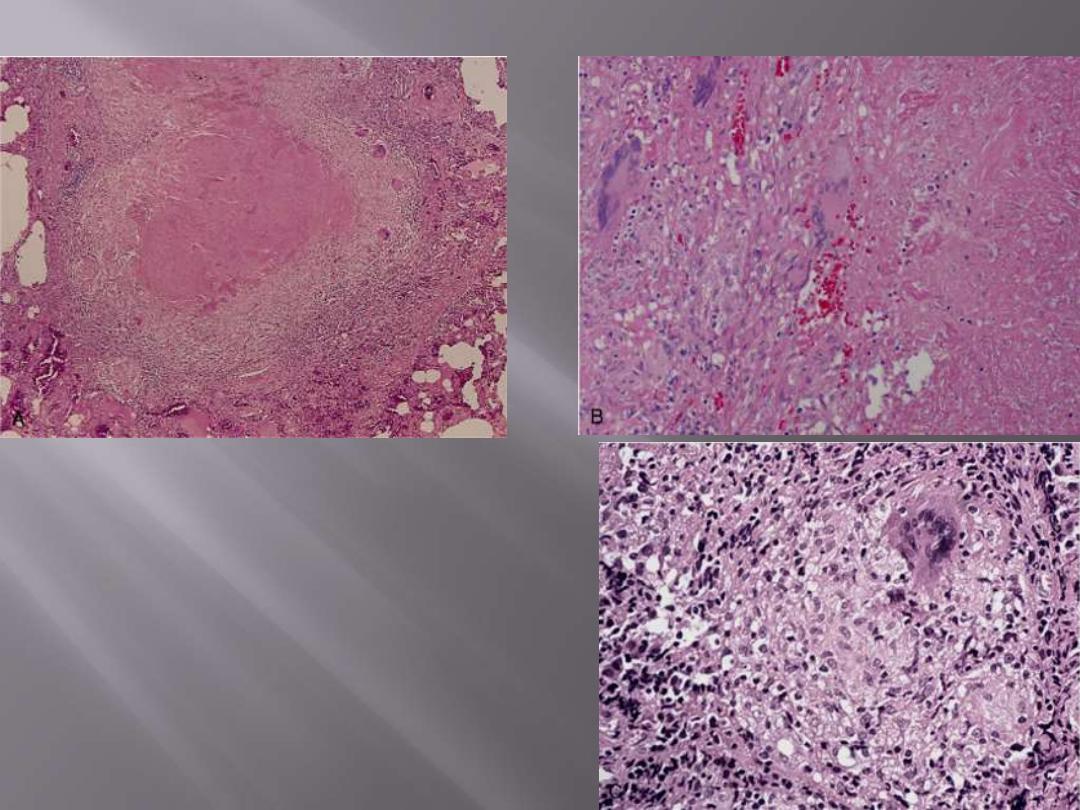

Microscopically,

there is the characteristic granulomatous

inflammatory reaction that forms both caseating

and noncaseating tubercles.

Individual tubercles are microscopic; it is only

when multiple granulomas coalesce that they

become macroscopically visible.

The granulomas are usually enclosed within a

fibroblastic rim with lymphocytes.

Multinucleate giant cells are present in the

granulomas.

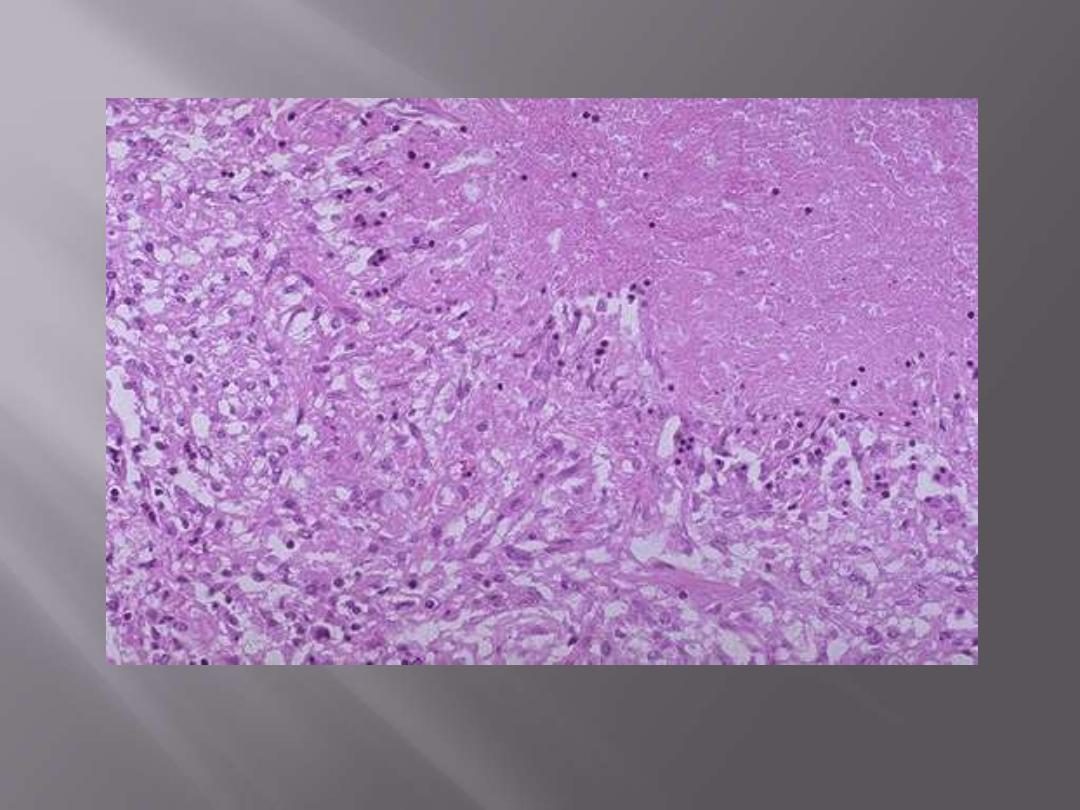

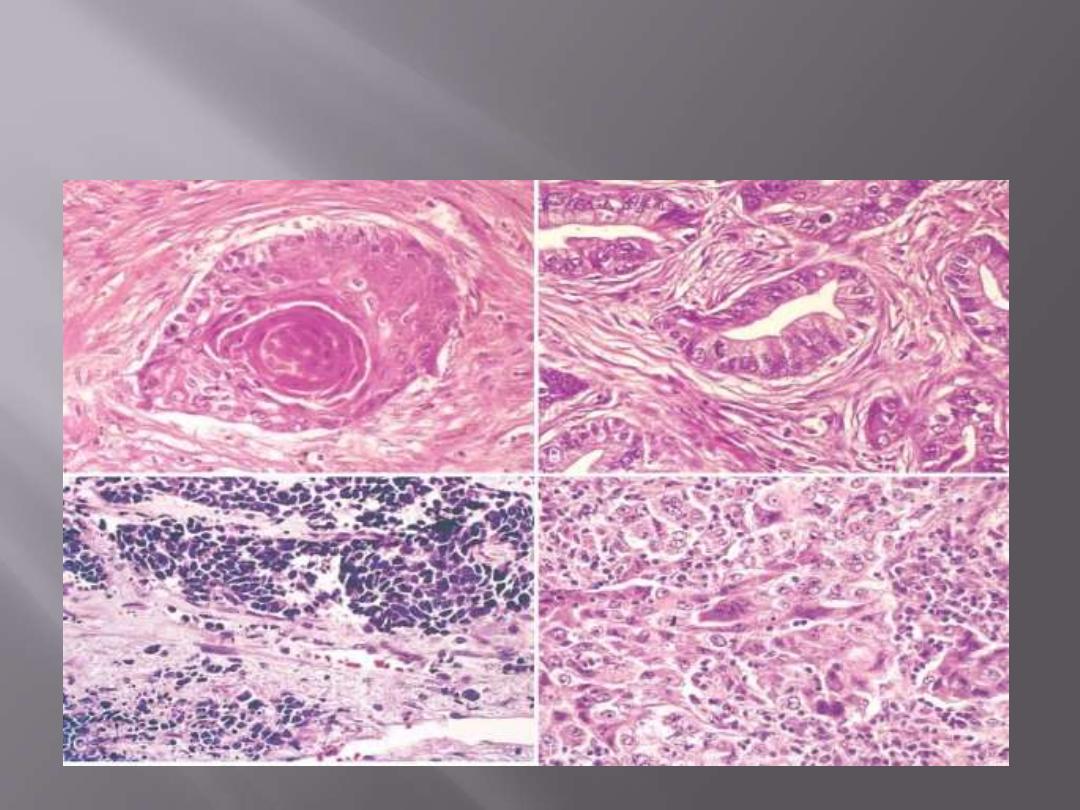

A characteristic tubercle at low magnification (A) and

in detail (B) illustrates central granular caseation

(right) that is surrounded by epithelioid and

multinucleated giant cells (left). This is the usual

response seen in individuals who have developed cell-

mediated immunity to the organism. C, Occasionally,

even in immunocompetent individuals, tubercular

granulomas may not show central caseation; hence,

irrespective of the presence or absence of caseous

necrosis, special stains for acid-fast organisms must

be performed when granulomas are present in

histologic sections.

The morphologic spectrum of tuberculosis

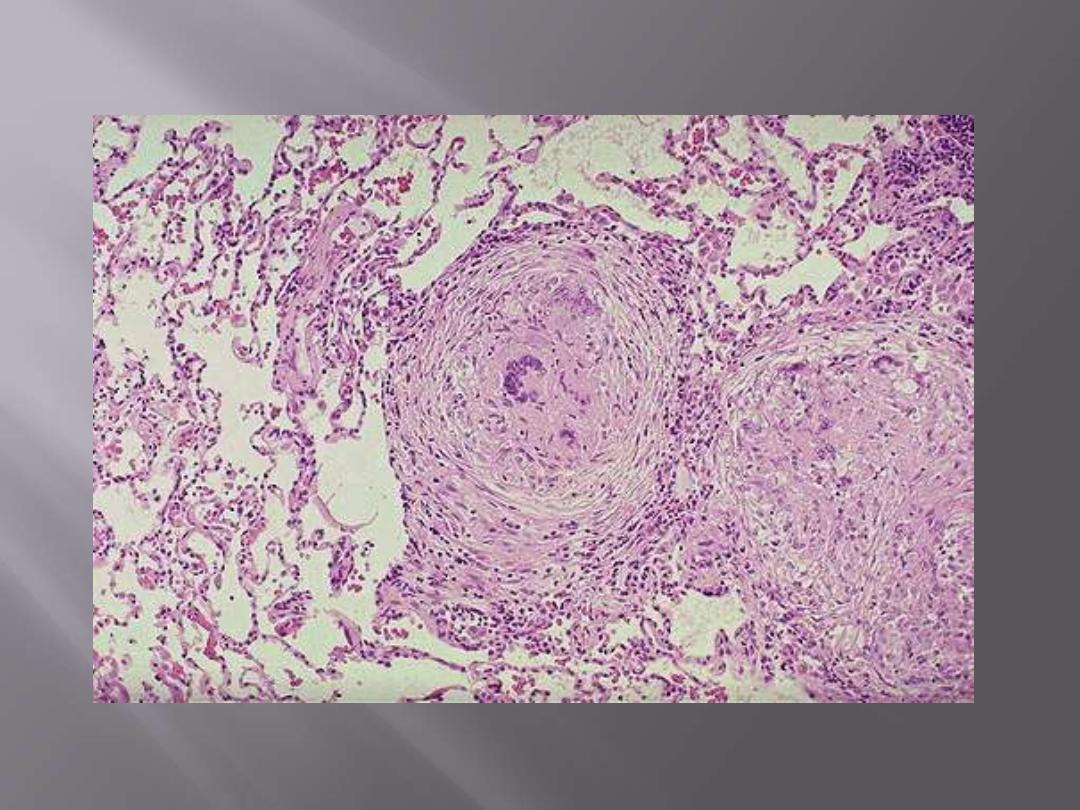

Multiple noncaseating epithelioid granuloma of TB

Note that the granulomas are enclosed within a fibroblastic rim with lymphocytes.

Microscopically, caseous necrosis is characterized by acellular pink areas of necrosis, as seen here at

the upper right, surrounded by a granulomatous inflammatory process.

Caseating epithelioid granuloma of TB

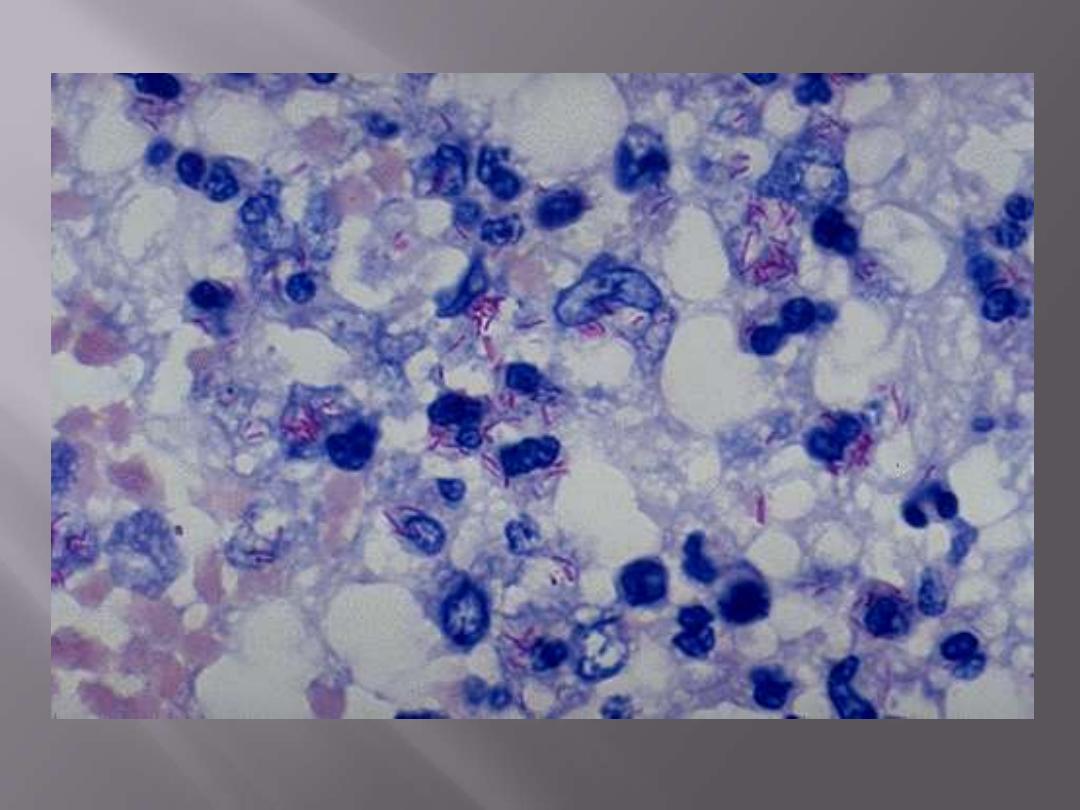

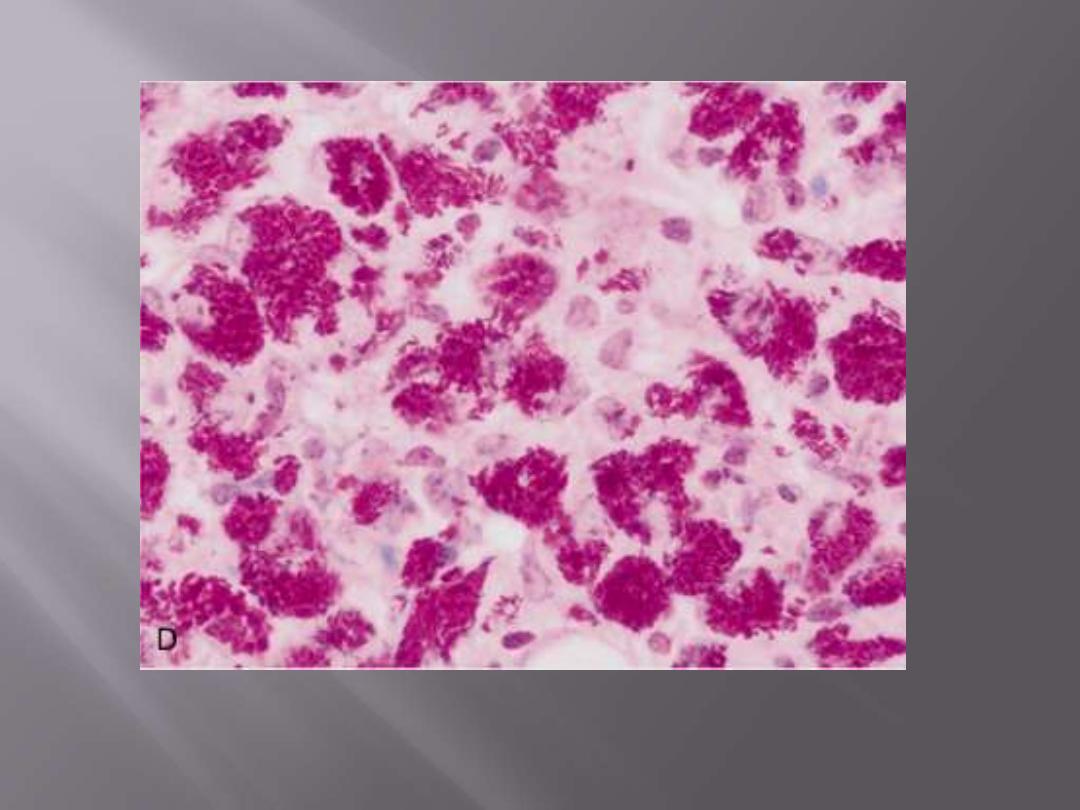

Mycobacterium tuberculosis: acid-fast stain

Note the red rods--hence the terminology acid fast bacilli (AFB)

In immunosuppressed individuals, tuberculosis may not elicit a granulomatous response ("nonreactive

tuberculosis"); instead, sheets of foamy histiocytes are seen, packed with mycobacteria that are

demonstrable with acid-fast stains.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis: acid-fast stain

The chief potential harmful outcomes of primary

tuberculosis are

1. Induction of destructive tissue hypersensitivity, which is more damaging on

subsequent infection

(secondary TB)

2. Healed foci of scarring may harbor viable bacilli for years, and thus be a

potential nidus for reactivation

when host defenses are compromised

3. The disease progresses relentlessly into

progressive primary tuberculosis

(uncommon). This occurs in

immunocompromised individuals e.g. AIDS

patients or in those with nonspecific impairment of host defenses

(malnourished children or elderly).

Immunosuppression results in the

absence of a tissue hypersensitivity reactio

n and thus there are no granulomas

but only sheets of foamy histiocytes packed with the bacilli

(nonreactive

tuberculosis).

Progressive primary tuberculosis often resembles acute bacterial pneumonia,

with lower and middle lobe consolidation, hilar lymphadenopathy, and

pleural effusion; cavitation is rare.

Lympho-hematogenous dissemination

may

result in the development of

tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis.

Secondary Tuberculosis (Postprimary) (Reactivation Tuberculosis)

previously sensitized host.

Pathogenesis

Reactivation of the dormant primary infection (as in nonendemic, low-

prevalence areas) or re-exposure to the bacilli in a previously sensitized host

(as in endemic areas) results in rapid recruitment of defensive reactions but

also tissue necrosis (caseation). This occurs when the protection (immunity)

offered by the primary infection is weakened.

only less than 5% with primary disease subsequently develop secondary

tuberculosis.

Secondary pulmonary tuberculosis is classically localized to the apex of one or

both upper lobes. This may relate to high oxygen tension in the apices

.

Because of the preexistence of hypersensitivity, the bacilli excite a marked

tissue response that tends to wall off the focus.

As a result of this localization,

the regional lymph nodes involvement is less prominent than they are in

primary tuberculosis.

Cavitation occurs readily in the secondary form

, & is almost inevitable in

neglected cases. As a result erosion of airways occurs; this converts the patient

into a source of infection to others; he now raises sputum containing bacilli.

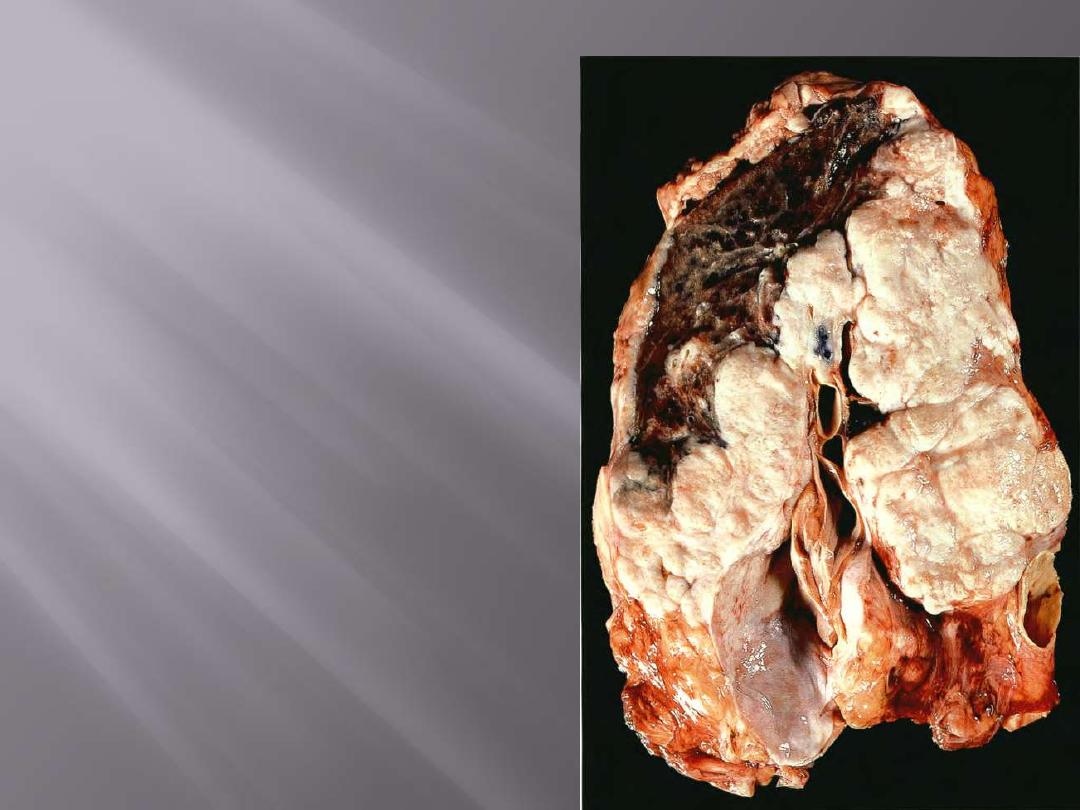

Gross features of secondary TB

The initial lesion is usually a small focus of consolidation,

less than 2 cm in diameter, near the apical pleura. Such

foci are sharply circumscribed, firm, and gray-white to

yellow areas that have a variable amount of central

caseation and peripheral fibrosis. This, if neglected

progresses to cavitations.

Microscopic features

The active lesions show characteristic coalescent tubercles

with central caseation. TB bacilli can be demonstrated by

specific staining methods.

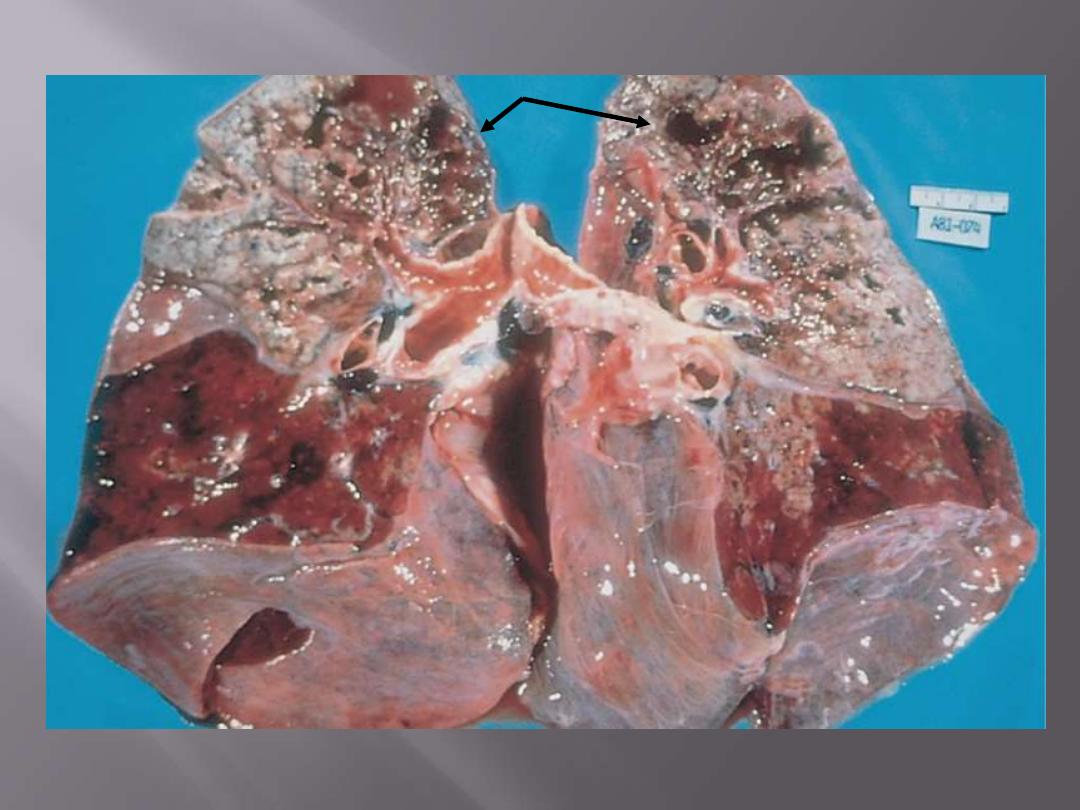

The upper parts of both lungs show multiple areas of softening and cavitation (arrows)

Secondary pulmonary tuberculosis

Progression of secondary TB

In favorable cases, the initial localized apical parenchymal damage undergoes

progressive healing by fibrosis & eventually represented by fibrocalcific scars.

This happy outcome occurs either spontaneously or after therapy.

Alternatively, the disease may progress and extend along several different

pathways:

A. Progressive pulmonary tuberculosis:

the apical lesion enlarges with

expansion of the area of caseation. Erosion into a bronchus evacuates the

caseous center, creating a ragged, irregular cavity lined by caseous material ;

whereas erosion of blood vessels results in hemoptysis. The pleural cavity is

always involved and serous pleural effusions, tuberculous empyema, or fibrous

obliteration may develop.

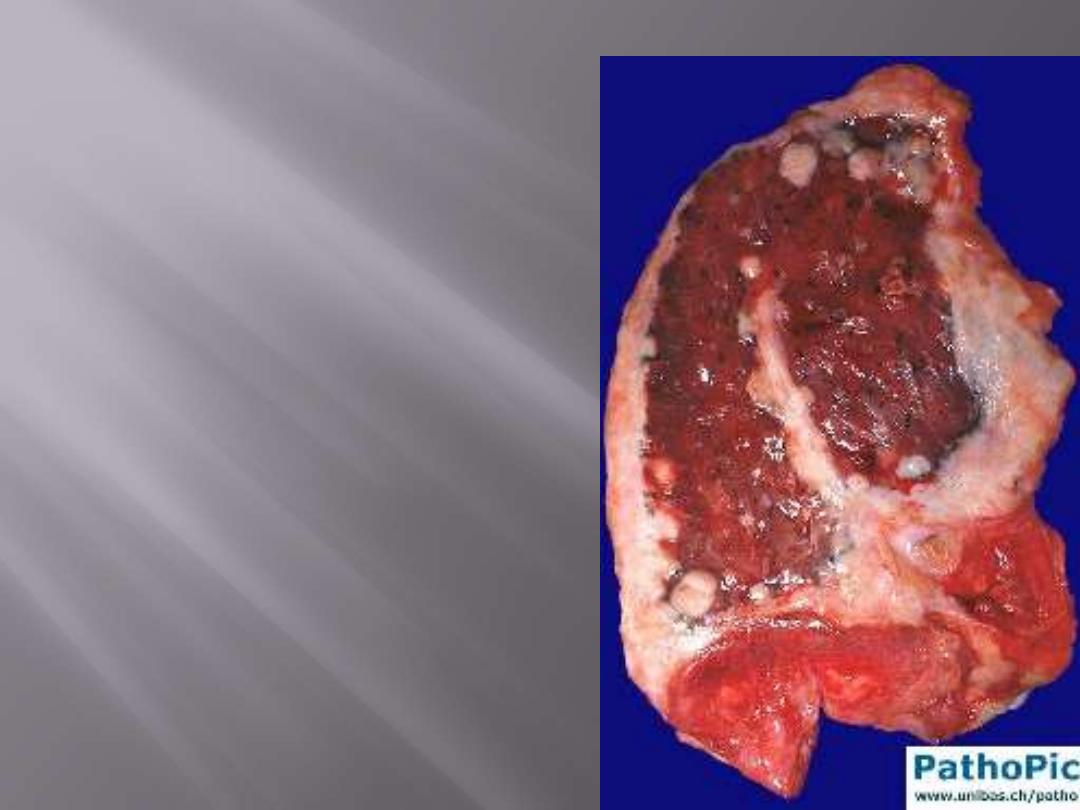

B. Miliary pulmonary disease

occurs when organisms drain through lymphatics

into the lymphatic ducts, which empty into the venous return to the right side

of the heart and thence into the pulmonary arteries. Individual lesions are

either microscopic or small (2-mm) foci of yellow-white; these scatter diffusely

through the lungs (miliary is derived from the resemblance of these foci to millet

seeds).

Miliary lesions may expand and coalesce to yield almost total

consolidation of large regions or even whole lobes of the lung.

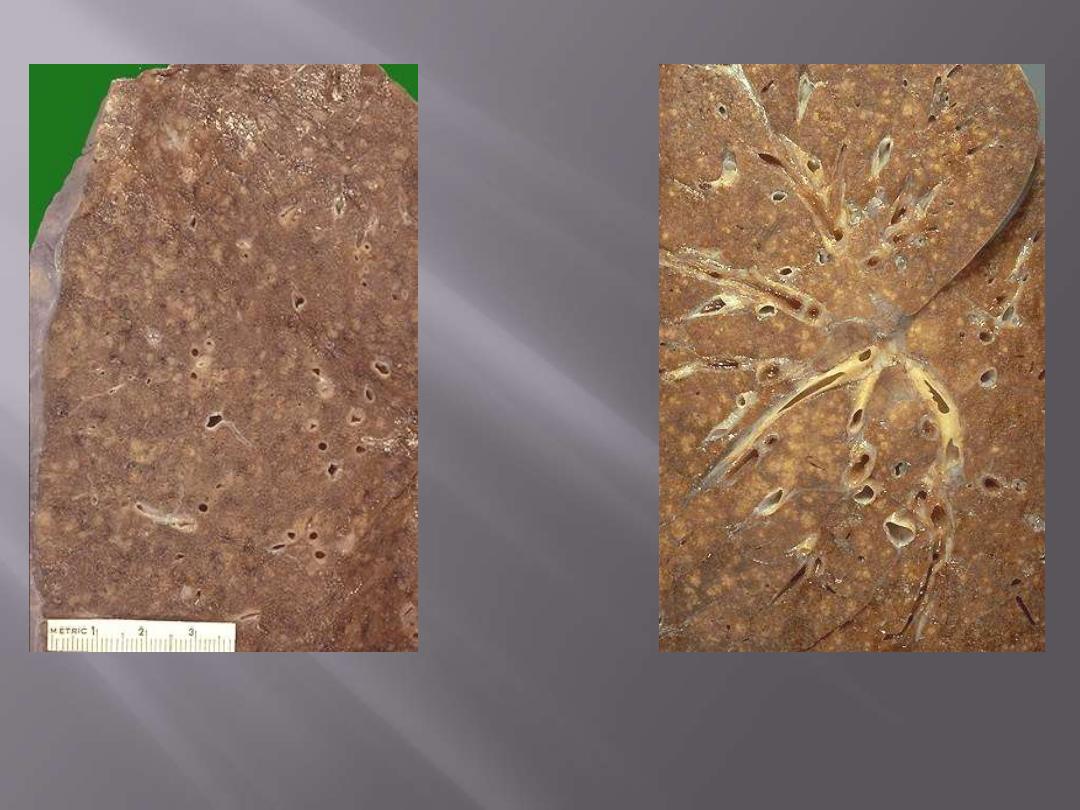

Lt. multitude of small (2 to 4 mm), yellow-white foci ; these scatter diffusely through the lungs. The

miliary pattern gets its name from the resemblance of the granulomas to millet seeds.

Rt. A zoom in appearance; the miliary pattern is seen throughout the lung.

Miliary pulmonary TB

C. Endobronchial, endotracheal,

and laryngeal tuberculosis may develop

when infective material is spread either through lymphatic channels or from

expectorated infectious material. The mucosal lining may be studded with

minute granulomatous lesions.

D. Systemic miliary tuberculosis

occurs when infective foci in the lungs

invade the pulmonary venous return to the heart; the organisms

subsequently disseminate through the systemic arterial system. Almost every

organ in the body may be seeded. The appearances are similar to miliary

pulmonary disease. Miliary tuberculosis is most prominent in the liver, bone

marrow, spleen , adrenals, meninges, kidneys, fallopian tubes, and

epididymis.

E. Isolated-organ tuberculosis

may appear in any one of the organs or tissues

seeded

hematogenously

and may be the presenting manifestation of

tuberculosis. Organs typically involved include the

meninges (tuberculous

meningitis), kidneys (renal tuberculosis), adrenals (formerly an important

cause of Addison disease), bones (tuberculous osteomyelitis), and fallopian

tubes (tuberculous salpingitis).

When the vertebrae are affected, the disease

is referred to as

Pott disease

. Paraspinal "cold" abscesses in persons with

this disorder may track along the tissue planes to present as an abdominal

or pelvic mass.

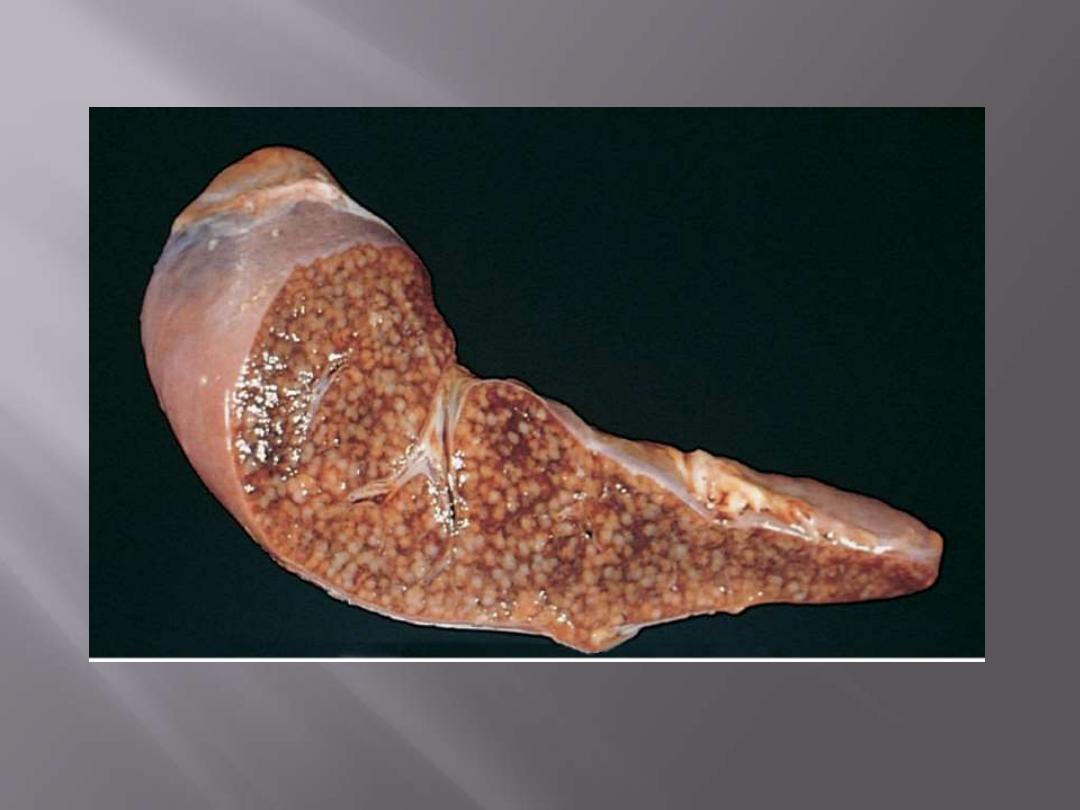

The cut surface shows numerous gray-white granulomas.

Miliary tuberculosis of the spleen

F. Tuberculous Lymphadenitis

is the most frequent form of

extrapulmonary tuberculosis, usually occurring in the cervical

region ("scrofula"). It tends to be unifocal, and most individuals

do not have evidence of ongoing extranodal disease.

H. Intestinal tuberculosis

was fairly common as a primary focus

of tuberculosis contracted by the drinking of contaminated milk.

In developed countries today, intestinal tuberculosis is more

often a

complication of protracted advanced secondary

tuberculosis,

secondary to the swallowing of coughed-up

infective material. Typically, the organisms are trapped in

mucosal lymphoid aggregates of the small and large bowel,

which then undergo inflammatory enlargement with ulceration

of the overlying mucosa,

particularly in the ileum.

The diagnosis of pulmonary disease

is based in part on the

history and on physical and radiographic findings of consolidation or

cavitation in the apices of the lungs. However,

tubercle bacilli must be

identified to establish the diagnosis.

The most common method for diagnosis of tuberculosis remains

demonstration of acid-fast organisms in sputum by special stains e.g. acid-

fast stain

; most protocols require at least two sputum examinations before

labeling the case as sputum negative.

Conventional cultures for mycobacteria require up to 10 weeks.

PCR amplification

of M. tuberculosis DNA allows for even greater rapidity

of diagnosis and is currently approved for use. PCR assays can detect as

few as 10 organisms in clinical specimens, compared with greater than

10,000 organisms required for smear positivity. However, culture remains

the gold standard because it also allows testing of drug susceptibility.

Prognosis

is generally favorable if infections are localized to the lungs,

but it worsens significantly when the disease occurs in the setting of

aged,

debilitated, or immunosuppressed persons, who are at high risk for

developing miliary tuberculosis, and in those with multi-drug resistant-TB.

Amyloidosis may appear in persistent cases.

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease

is mostly in the form of chronic but clinically localized

pulmonary disease in immunocompetent individuals.

Strains implicated most frequently include M. avium-

intracellulare.

Nontuberculous mycobacteriosis may present as upper

lobe cavitary disease, mimicking tuberculosis, especially in

individuals with a long-standing history of smoking or

alcoholism.

The presence of concomitant chronic pulmonary disease

e.g. COPD, is an important risk factor.

In immunosuppressed individuals (primarily, HIV-positive

patients), M. avium-intracellulare presents as disseminated

disease, associated with systemic symptoms.

LUNG TUMORS

Bronchial carcinomas

constitute

95%

of primary lung

tumors; the remaining

5%

includes

bronchial carcinoids,

sarcomas, lymphomas

, and a few benign lesions.

Pulmonary Hamartoma

is the most common benign lesion;

it is rounded

small (3-4 cm)

discrete mass that often displayed as "coin" lesion on chest

radiographs.

They consist mainly of mature cartilage with a scattered of

bronchial glands that are often admixed with fat, fibrous

tissue, and blood vessels in varying proportions.

Here are two examples of a benign lung neoplasm known as a pulmonary hamartoma. These

uncommon lesions appear on chest radiograph as a "coin lesion" that has a differential diagnosis of

granuloma and localized malignant neoplasm. They are firm and discreet and often have calcifications

in them that also appear on radiography. Most are small (less than 2 cm).

Pulmonary hamartoma

The pulmonary hamartoma is seen microscopically to be composed mostly of benign cartilage

on the right that is jumbled with a fibrovascular stroma and scattered bronchial glands on the

left. A hamartoma is a neoplasm in an organ that is composed of tissue elements normally found

at that site, but growing in a haphazard mass.

Pulmonary hamartoma

Carcinomas

Carcinoma of the lung is the commonest cause of cancer-

related deaths in industrialized countries.

The rate of increase among males is slowing down, but it

continues to accelerate among females; it has overrun breast

cancer as a cause of death since 1987.

This is undoubtedly related to the strong relationship of

cigarette smoking and lung cancer.

Most patients are in the age group of

50-60 years.

The prognosis of lung cancer is very poor: the 5-year survival

rate for all stages combined is about 15%.

Squamous cell carcinoma ( 25-40%).

Adenocarcinoma (25-40%)

Small cell carcinoma (20-25%)

Large cell carcinoma (10-15%)

There are four major histologic types of lung carcinomas

1. Squamous cell carcinoma

2. Adenocarcinoma

3. Small-cell carcinoma

4. Large-cell carcinoma.

Adenocarcinomas are the most common primary tumors arising in women,

in lifetime nonsmokers, and in persons younger than 45 years.

For therapeutic purposes, carcinomas of the lung are divided into two groups:

small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

The

latter category includes

squamous cell, adenocarcinomas, and large-cell

carcinomas.

The reason for this division is that virtually

all SCLCs have metastasized by

the time of diagnosis

and hence are

not curable by surgery

. Therefore, they

are best treated by

chemotherapy, with or without radiation.

NSCLCs usually respond poorly to chemotherapy and are better treated by

surgery.

These two groups show genetic differences.

SCLCs are characterized by a high frequency of

RB gene mutations

, while

the

p16 gene

is commonly inactivated in NSCLCs.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

It seems that large areas of the respiratory mucosa have undergone

mutation after exposure to carcinogens

("field effect").

On this fertile soil, those cells that accumulate additional mutations

ultimately develop into cancer.

The role of Cigarette smoking

is the main agent responsible for the genetic changes that give rise to lung

cancers.

About

90%

of lung cancers occur in active smokers (or those who stopped

recently).

The increased risk is

60 times

greater among habitual heavy smokers (two

packs a day for 20 years) compared with nonsmokers.

Women have a higher susceptibility to carcinogens in tobacco than men.

Although cessation of smoking decreases the risk of developing lung cancer

over time, genetic changes that predate lung cancer can persist for many

years in the bronchial epithelium of ex-smokers.

Passive smoking

(proximity to cigarette smokers)

increases the risk to twice that of nonsmokers.

There is a linear correlation between the intensity

of smoking and the appearance of squamous

metaplasia that progresses to squamous dysplasia

and carcinoma in situ,

before culminating in

invasive cancer.

Squamous and small-cell carcinomas show the

strongest association with tobacco exposure.

The role of occupation-related environmental agents;

These may act

alone

or

synergistically

with smoking to be

pathogenitically related to some lung cancers, for e.g.

radioactive ores;

dusts containing arsenic, chromium, uranium, nickel, vinyl chloride, and

mustard gas.

Exposure to

asbestos increases the risk of lung cancer 5 times in

nonsmokers.

However, heavy smoking with asbestos exposure increases

the risk to

50 times.

The role of hereditary (genetic) factors

:

not all persons exposed to tobacco smoke develop cancer.

It seems that the effect of carcinogens is modulated by hereditary

(genetic) factors.

Many procarcinogens require metabolic activation via the

P-450 enzyme

system for conversion into carcinogens.

Evidences support this scenario in that persons with specific genetic

abnormalities of P-450 genes have an increased capacity to metabolize

procarcinogens derived from cigarette smoke and thus sustain the

greatest risk of developing lung cancer.

The role of bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) in

the development of peripheral adenocarcinoma:

the

"cell of origin"

for peripheral adenocarcinomas is the

BASCs.

Following peripheral lung injury, the multipotent BASCs

undergo expansion to replenish the normal cell types

found in this location, thereby facilitating epithelial

regeneration.

BASCs are considered the tumor initiating cells i.e. the

first to acquire the somatic

K-RAS mutation

that enables

their daughter cells to

escape normal "checkpoint"

mechanisms and result in pulmonary adenocarcinomas.

Gross Features

Carcinomas of the lung begin as small mucosal lesions that are usually firm

and gray-white. Further enlargement result in either intraluminal masses,

or invasion of the bronchial wall to form large bulky masses pushing into

adjacent lung parenchyma.

Obstruction of the bronchial lumen often

produces distal atelectasis and infection.

Some tumors tend to a

rise centrally near the hilum

i.e. in major brochi,

these are exemplified by

squamous cell & small cell carcinomas

.

Adenocarcinomas

may occur

centrally but are usually more peripherally

located,

many arising in relation to peripheral lung scars

("scar

carcinomas").

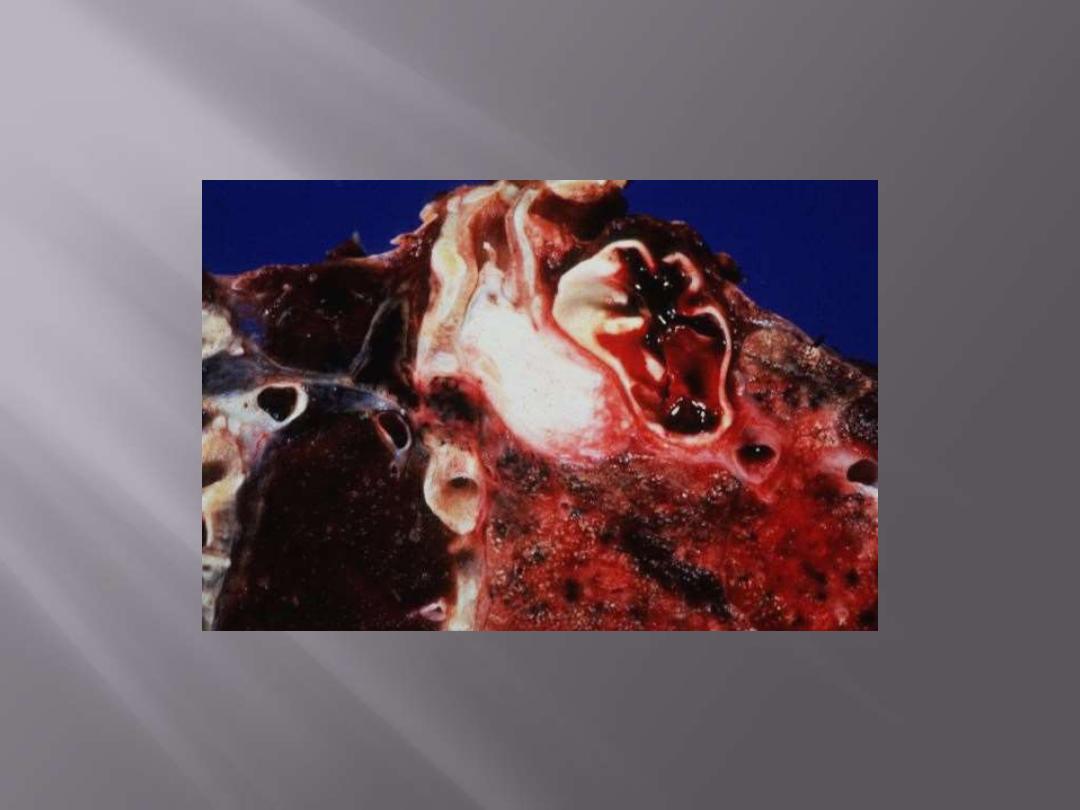

Large tumors may undergo cavitation; this is caused by central necrosis.

These tumors may extend to the pleura, invade the pleural cavity and chest

wall, and spread to adjacent intrathoracic structures.

Metastasis occurs first to

peribronchial, hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes

More distant spread can occur via the

lymphatics or the hematogenous

route.

Squamous cell carcinoma: Note whitish endobronchial obstructive mass.

Early bronchial carcinoma

This is a fairly small carcinoma which has arisen in a bronchus blue (arrow), and then invaded into

surrounding lung tissue; tumor obstructing bronchus

Early bronchial carcinoma

The tumor usually begin as central (hilar) masses and grow contiguously into the peripheral

parenchyma and adjacent pleura

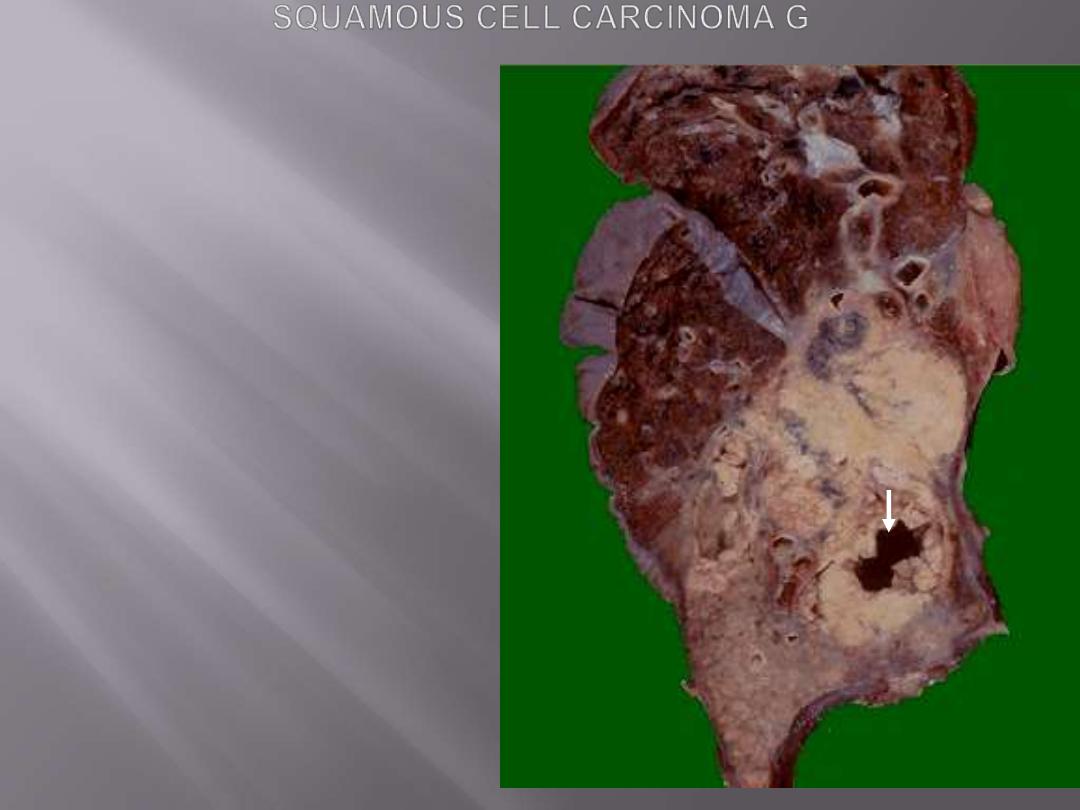

Squamous cell carcinomas

This is a large squamous cell carcinoma in

which a portion of the tumor demonstrates

central cavitation (arrow), probably because

the tumor outgrew its blood supply.

Squamous cell carcinoma showing large central area of necrosis and cystic change.

Squamous cell carcinoma

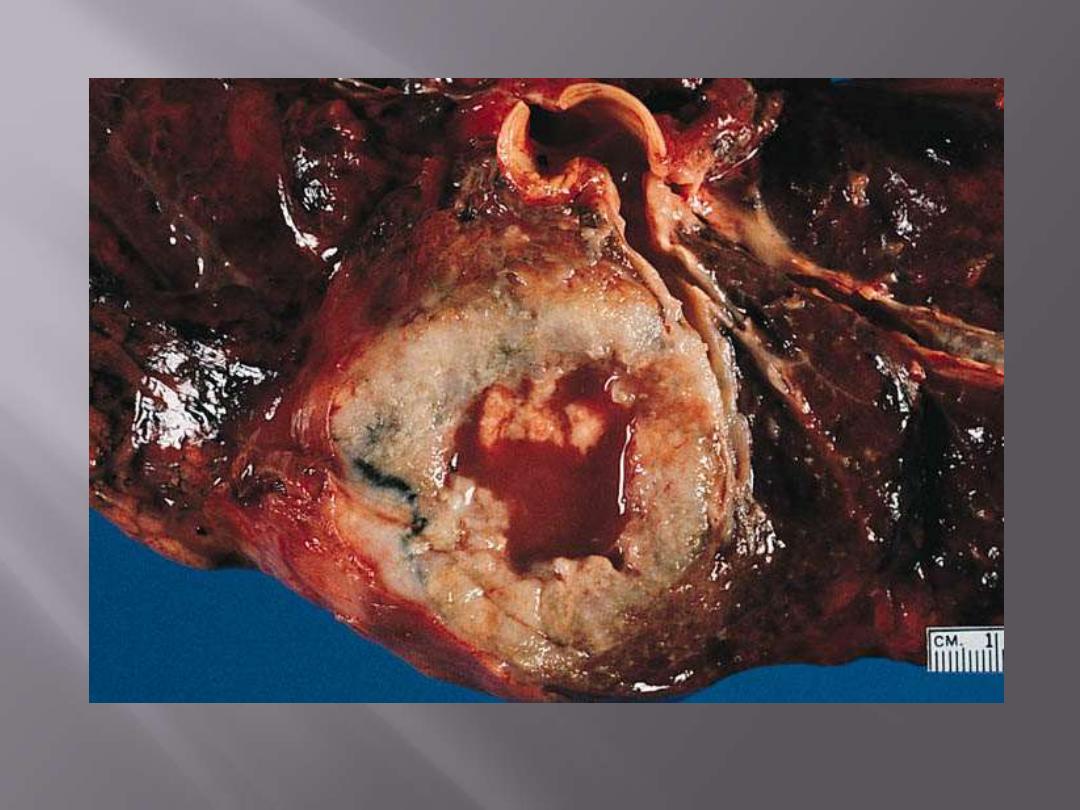

This pale white tumor is obstructing the right main

bronchus. a squamous cell carcinoma of the lung that is

arising centrally in the lung (as most squamous cell

carcinomas do). Microscopy shows squamous cell

carcinoma.

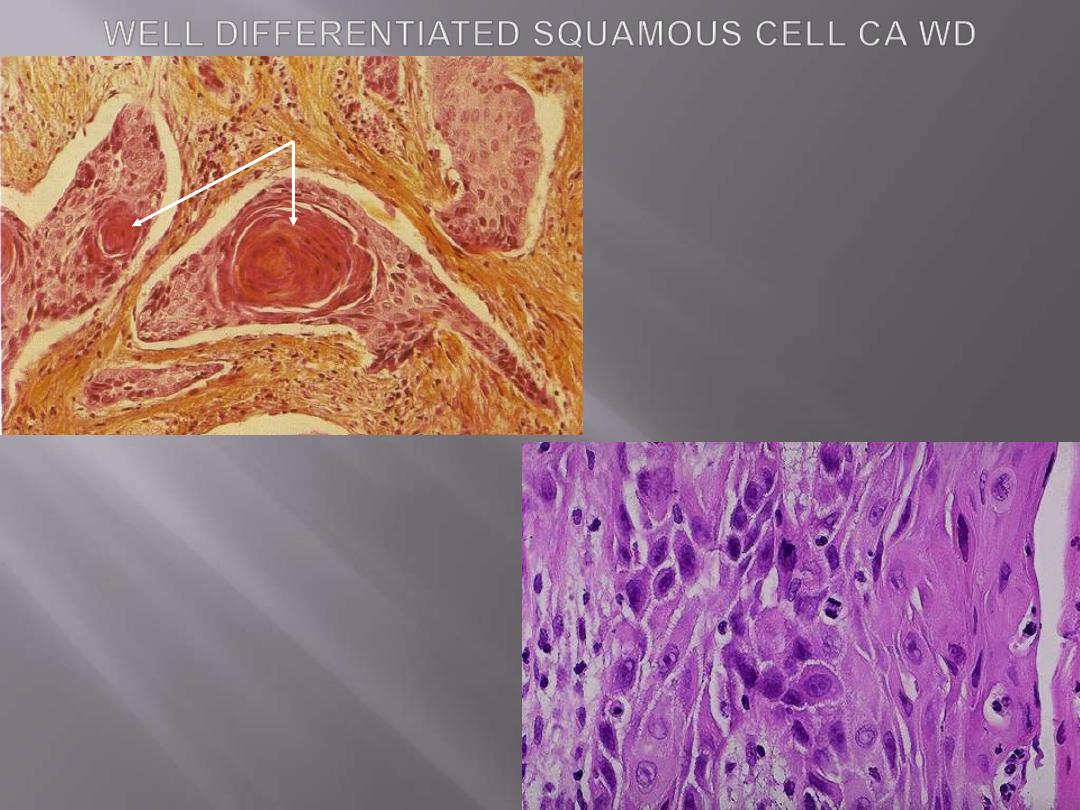

Microscopic features

Squamous cell carcinomas

are often preceded for years by

squamous metaplasia

or dysplasia in the bronchial epithelium

, which then

transforms to

carcinoma in situ,

a phase that may last

for several years.

These tumors range from

well-differentiated showing

keratin pearls and intercellular bridges to poorly

differentiated neoplasms having only minimal

residual squamous cell features.

Above: nests of squamous cells with keratin

production (arrow).

Below: the pink cytoplasm with distinct cell

borders and intercellular bridges

characteristic for a squamous cell

carcinoma are seen here at high

magnification. Such features are seen in

well-differentiated tumors (those that more

closely mimic the cell of origin).

Adenocarcinomas

assume a variety of forms, including

gland

forming (acinar), papillary, and solid types.

The solid variant often requires demonstration

of

intracellular mucin

production by special

stains to establish its adenocarcinomatous

nature.

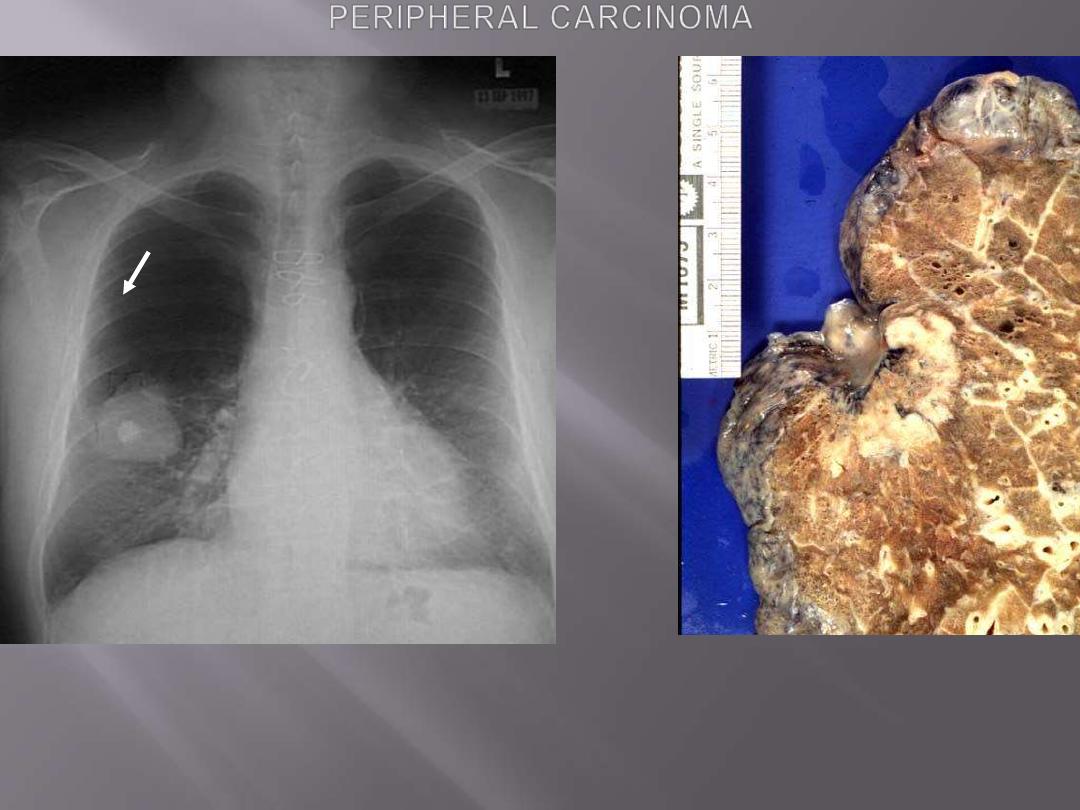

Rt. This chest radiograph demonstrates a large 5 cm diameter adenocarcinoma of the right lower lobe.

The bright opacity in the middle of the mass is a calcified granuloma.

Lt. Adenocarcinoma: Peripheral mass located immediately under visceral pleura, with pleural

retraction.

Adenocarcinoma. The tumor is peripherally located and

has extended to the pleura.

Peripheral carcinoma

Malignant epithelial cells forming glandular

structures with mucin secretion.

Pulmonary adenocarcinoma

papillary and micropapillary structures

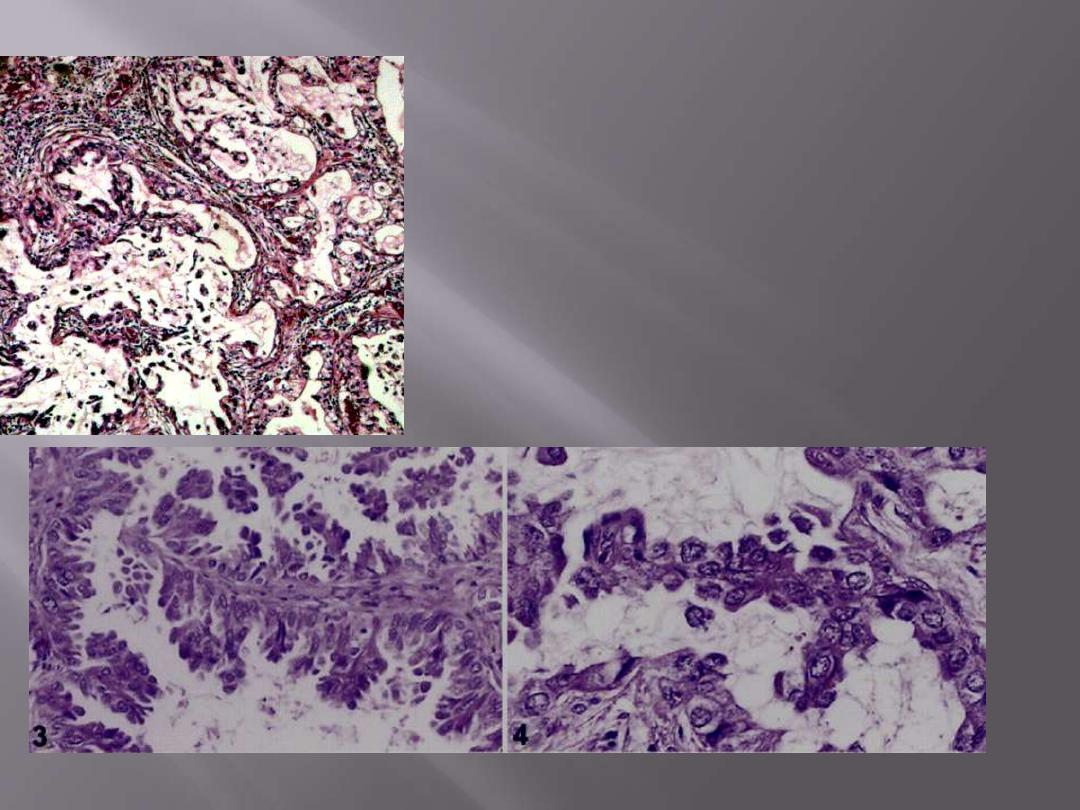

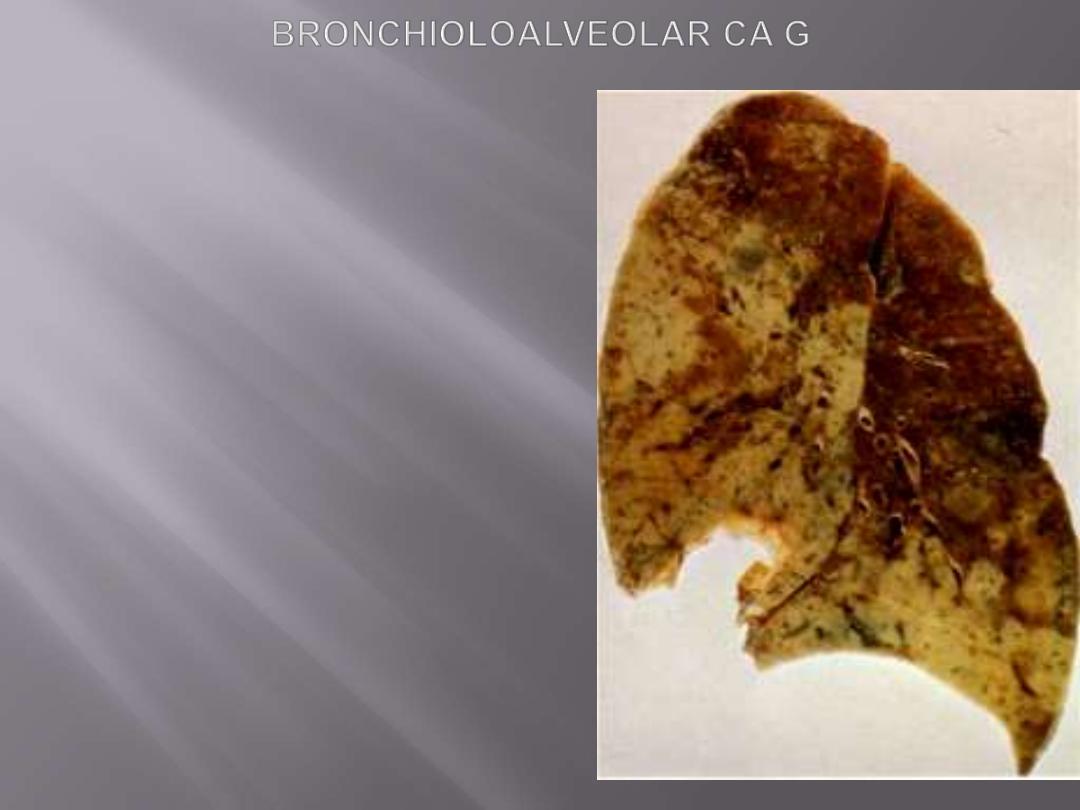

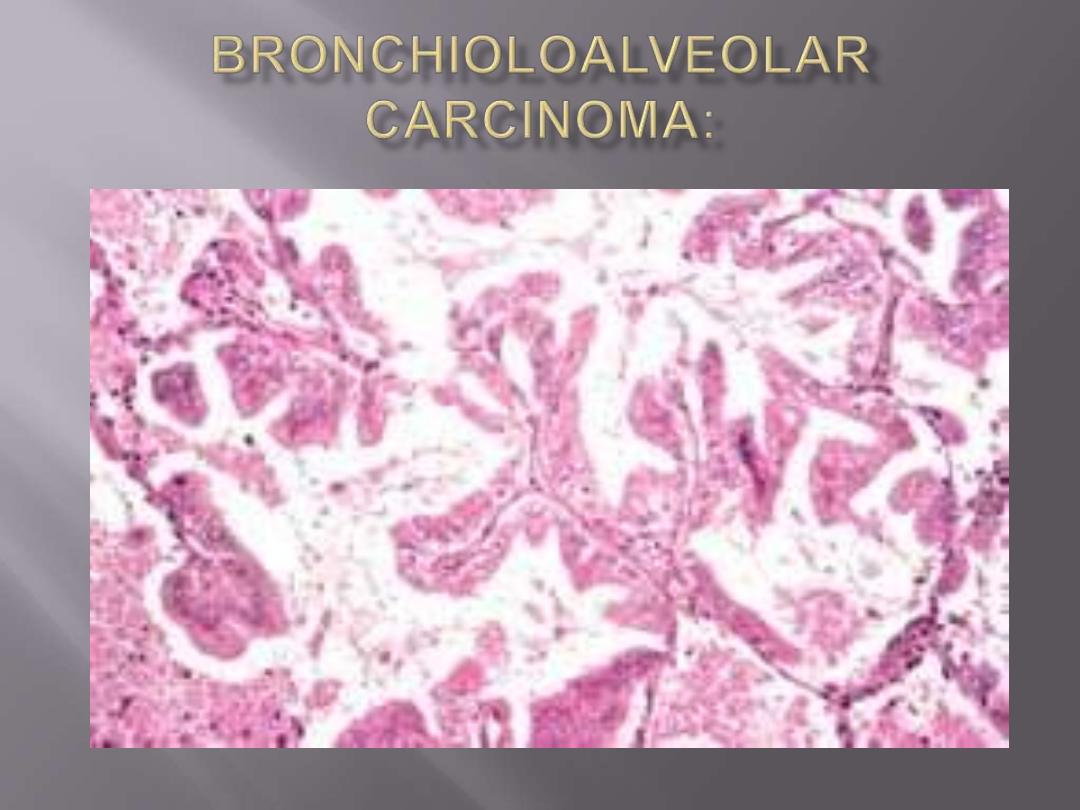

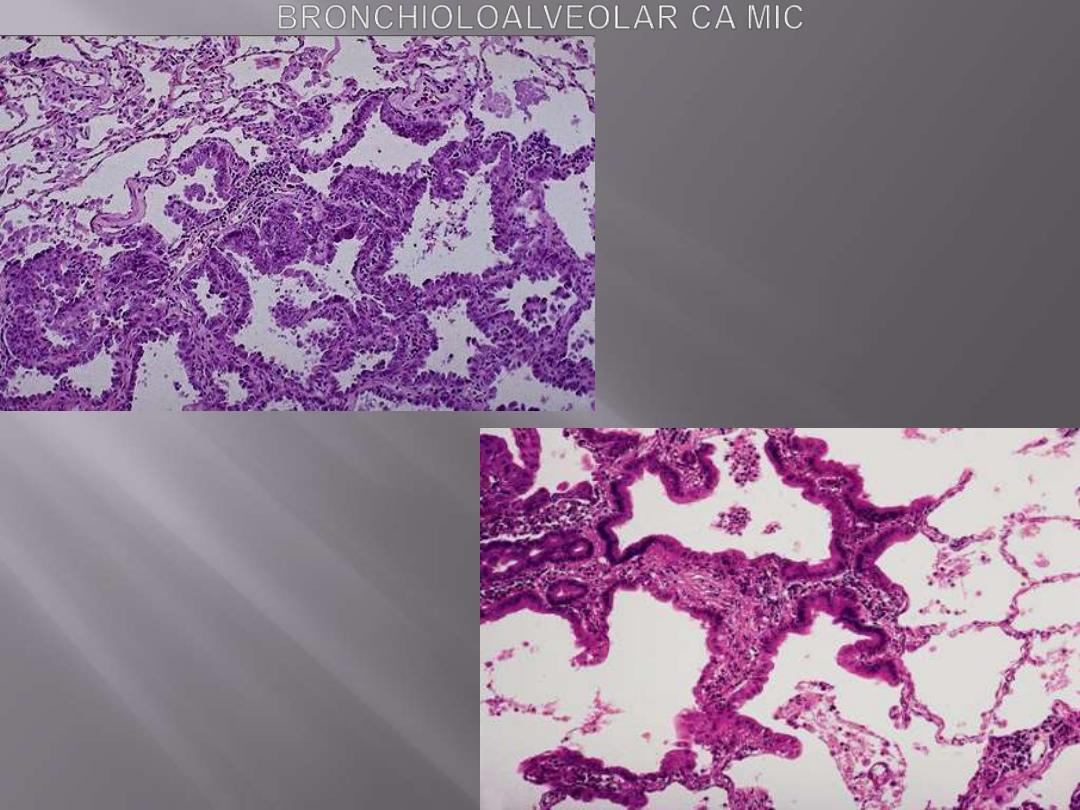

Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas (BACs)

are a subtype of adenocarcinomas.

They involve

peripheral parts of the lung, either as a

single nodule or, more often, as multiple diffuse

nodules that may coalesce to produce pneumonia-

like consolidation.

The key feature of BACs is their growth

along

preexisting structures and preservation of alveolar

architecture.

Greyish-white tumor involves 2/3 of left upper lobe and

1/3 of the lower lobe. The color and distribution suggest

pneumonic consolidation. Secondary tumors can

peoduce the same appearance.

The tumor is composed of columnar cells

that proliferate along the framework of

alveolar septae. The cells are well-

differentiated.

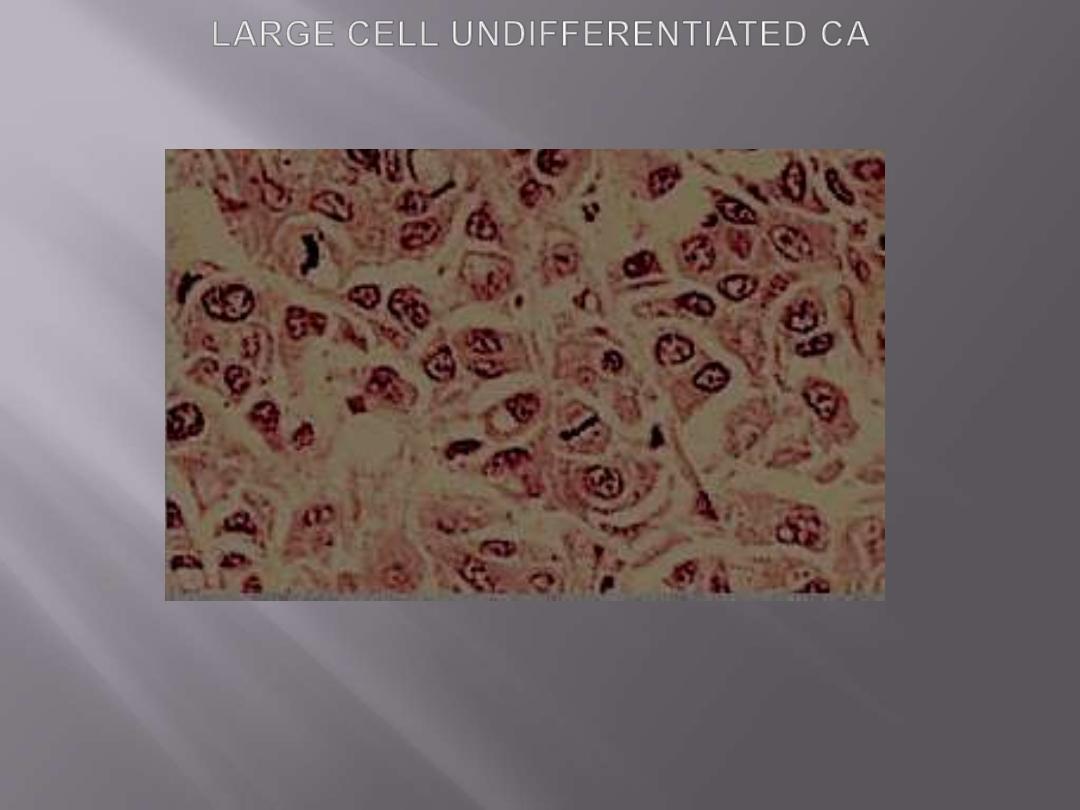

Large-cell carcinomas

undifferentiated malignant epithelial tumors that lack

the cytologic features of glandular or squamous

differentiation

.

The cells have large nuclei, prominent nucleoli.

Large-cell

carcinomas

probably

represent

undifferentiated examples of squamous cell or

adenocarcinomas at the light microscopic level.

Ultrastructurally, however, minimal glandular or

squamous differentiation is common.

Undifferentiated large cell carcinoma. Tumor is formed by large cells growing in solid nests without

evidence of glandular or squamous differentiation.

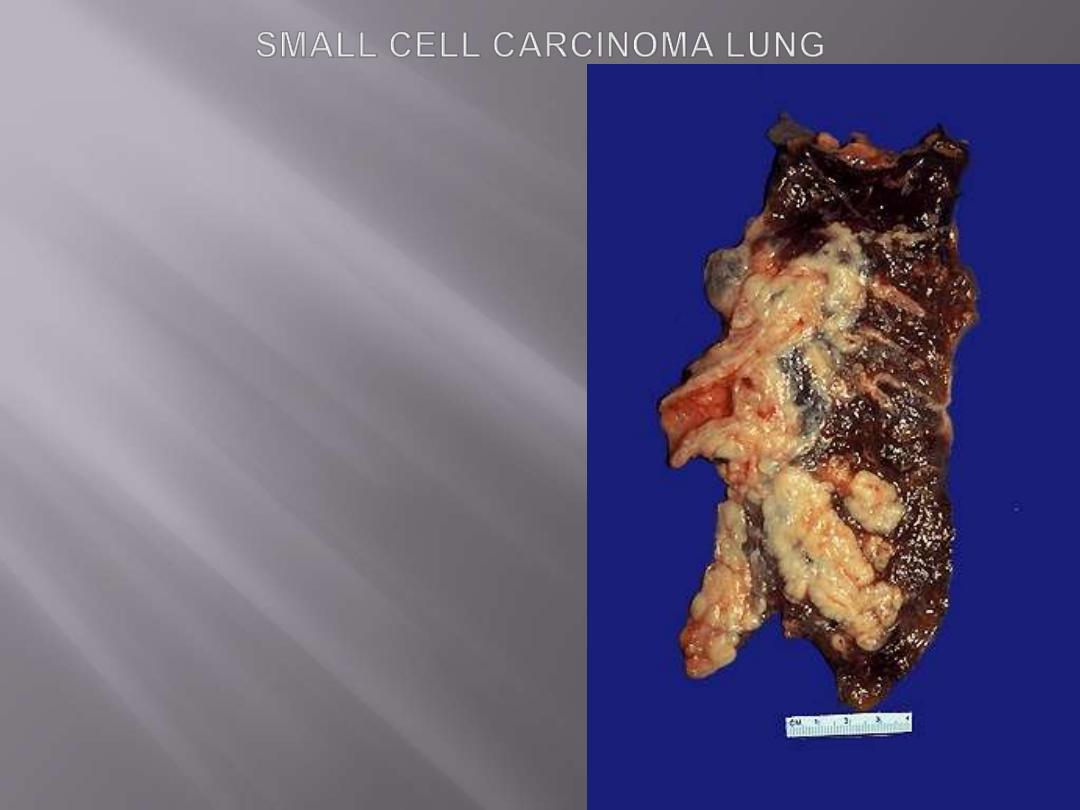

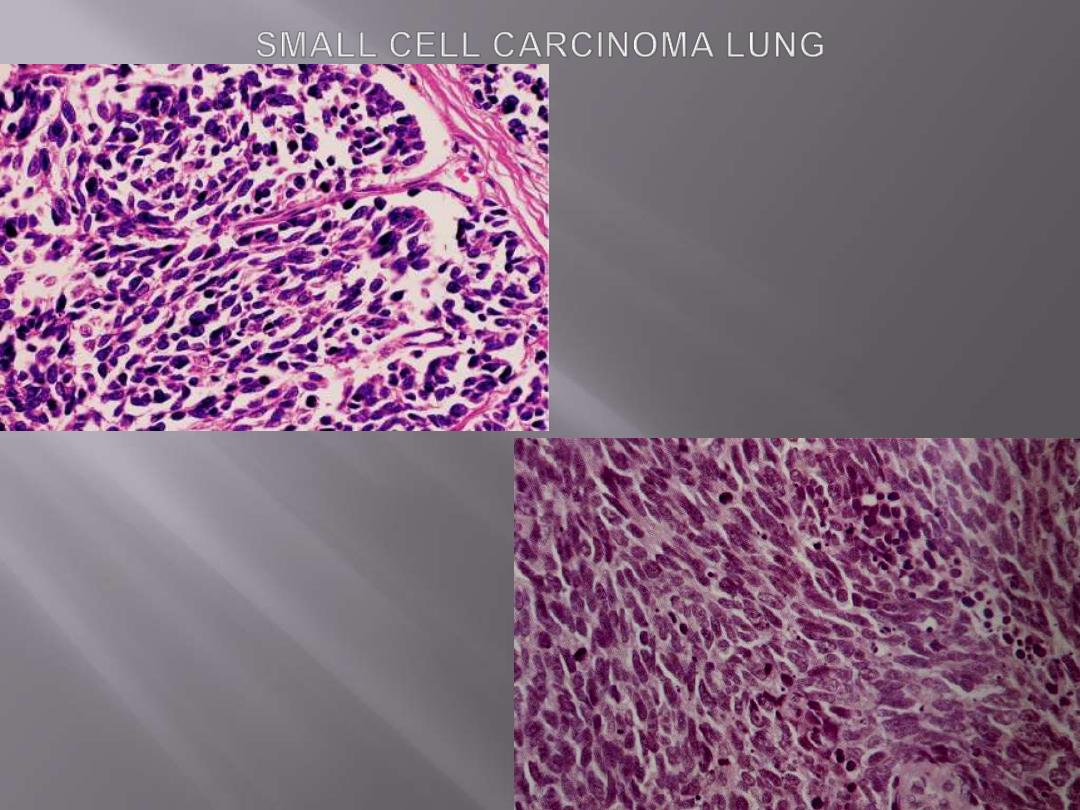

Small-cell lung carcinomas

are composed of small tumor cells with a round to

fusiform nuclei with finely granular chromatin, and

scant cytoplasm.

Mitotic

figures are frequently seen.

Despite the term of

"small,"

the neoplastic cells are

usually

twice the size of resting lymphocytes.

Necrosis

is invariably present and may be extensive.

These tumors are derived from

neuroendocrine cells

of the lung, and hence they express a variety of

neuroendocrine markers in addition to many

polypeptide

hormones

that

may

result

in

paraneoplastic syndromes.

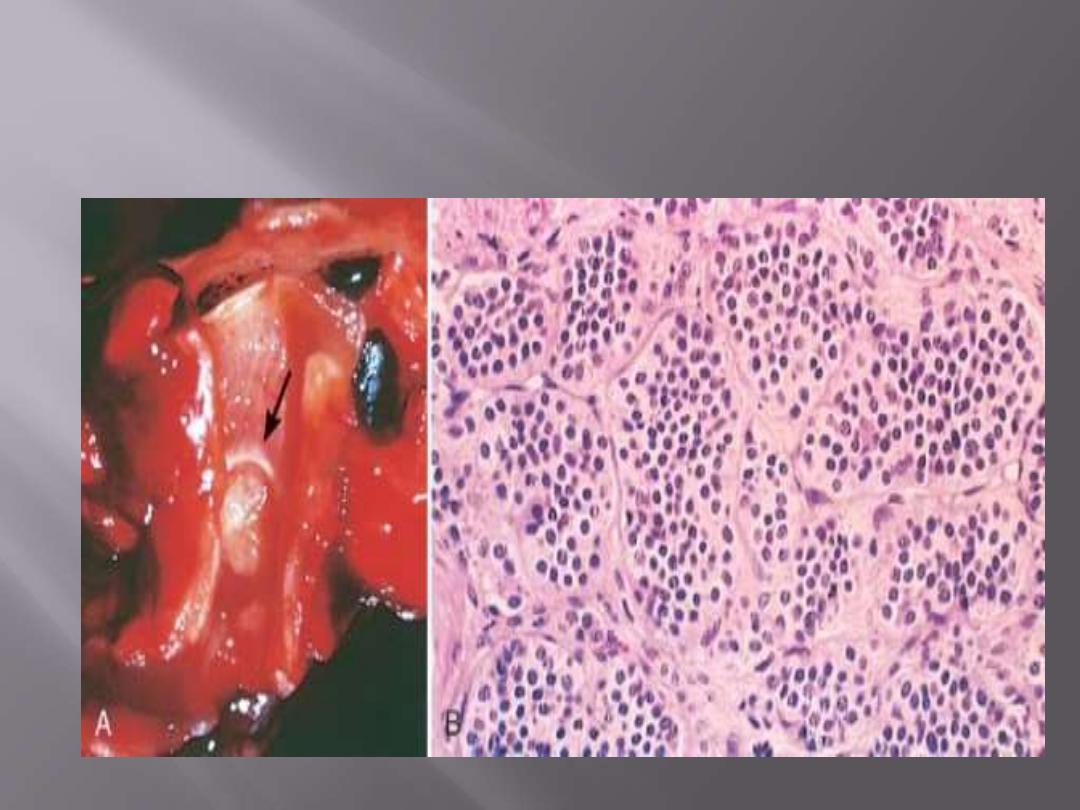

Arising centrally in this lung and spreading

extensively is a small cell anaplastic (oat cell)

carcinoma. The cut surface of this tumor has a

soft, lobulated, white to tan appearance. The

tumor seen here has caused obstruction of the

main bronchus to left lung so that the distal

lung is collapsed. Oat cell carcinomas are very

aggressive and often metastasize widely before

the primary tumor mass in the lung reaches a

large size.

The tumor is composed of small cells with darkly

staining oval to spindle nuclei and extremely scanty

cytoplasm.

Combined tumors:

a minority of bronchogenic carcinomas reveal

more than one line of differentiation, sometimes

several, suggesting that all are derived from a

multipotential progenitor cell.

All subtypes of lung cancer show involvement of successive

chains of nodes about the

carina, in the mediastinum, and

in the neck (scalene nodes) and clavicular regions and,

sooner or later, distant metastases.

Involvement of the

left supraclavicular node (Virchow node)

is particularly characteristic and sometimes calls attention

to an occult primary tumor.

These cancers, when advanced, often extend into the

pericardial or pleural spaces, leading to inflammation and

effusions.

They may compress or infiltrate the superior vena cava to

cause either venous congestion or the full-blown

vena caval

syndrome.

Apical neoplasms

may invade the brachial or cervical

sympathetic plexus to cause severe pain in the distribution

of the ulnar nerve or to produce

Horner syndrome

(ipsilateral enophthalmos, ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis).

Such apical neoplasms are sometimes called

Pancoast

tumors,

and the combination of clinical findings is known as

Pancoast syndrome.

Pancoast tumor is often accompanied by destruction of the

first and second ribs and sometimes thoracic vertebrae.

As with other cancers, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM)

categories have been established to indicate the size and

spread of the primary neoplasm.

Course & prognosis

Carcinomas of the lung are silent lesions that more often than not have

spread beyond curable resection at the time of diagnosis.

Too often, the tumor presents with symptoms related to metastatic

spread to the brain (mental or neurologic changes), liver

(hepatomegaly), or bones (pain).

Overall, NSCLCs have a better prognosis than SCLCs.

NSCLCs

(squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas) are

detected before metastasis or local spread, cure is possible by

lobectomy or pneumonectomy.

SCLCs

, on the other hand, is almost always have spread by the time of

the diagnosis, even if the primary tumor appears small and localized.

Thus, surgical resection is not a practical treatment. They are very

sensitive to chemotherapy but invariably recur. Median survival even

with treatment is 1 year.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Up to

10%

of all patients with lung cancer develop clinically overt

paraneoplastic syndromes. These include

1. Hypercalcemia

caused by secretion of a parathyroid hormone-related

peptide.

2. Cushing syndrome

(from increased production of ACTH);

3. Inappropriate secretion of ADH

4. Neuromuscular syndromes,

including a myasthenic syndrome,

peripheral neuropathy, and polymyositis

5. Clubbing of the fingers and hypertrophic pulmonary

osteoarthropathy

6. Hematologic manifestations,

including migratory thrombophlebitis,

nonbacterial endocarditis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Hypercalcemia is most often encountered with squamous cell carcinomas, the

hematologic syndromes with adenocarcinomas. The remaining syndromes are

much more common with small-cell neoplasms, but exceptions occur.

Bronchial Carcinoids

are thought to arise from the

Kulchitsky cells

(neuroendocrine cells) of the

bronchial mucosa and represent about

5% of all pulmonary neoplasms.

The mean age of occurrence is

40 years.

Ultrastructurally,

the neoplastic cells contain cytoplasmic dense-core

neurosecretory granules and may secrete hormonally active polypeptides.

In contrast to the more ominous small-cell carcinomas, carcinoids are often

resectable and curable.

Gross features

Most bronchial carcinoids originate in main bronchi and grow in one of two

patterns

1. An Obstructing spherical, intraluminal mass

2. A mucosal plaque penetrating the bronchial wall to fan out in the peribronchial

tissue.

Some tumors, (about 10%) metastasize to hilar nodes but distant metastasis is

rare.

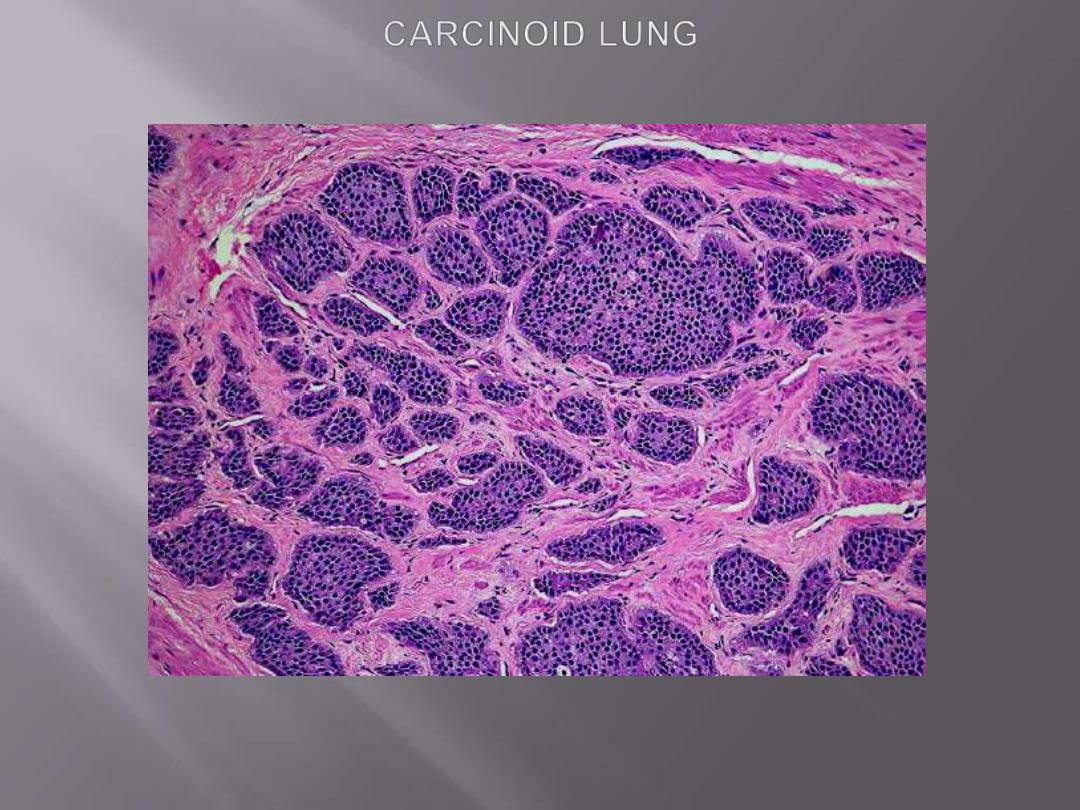

Microscopic features

They are composed of nests of uniform cells that have regular round

nuclei with

"salt-and pepper"

chromatin, absent or rare mitoses

A subset designated atypical carcinoid that differ from the typical by

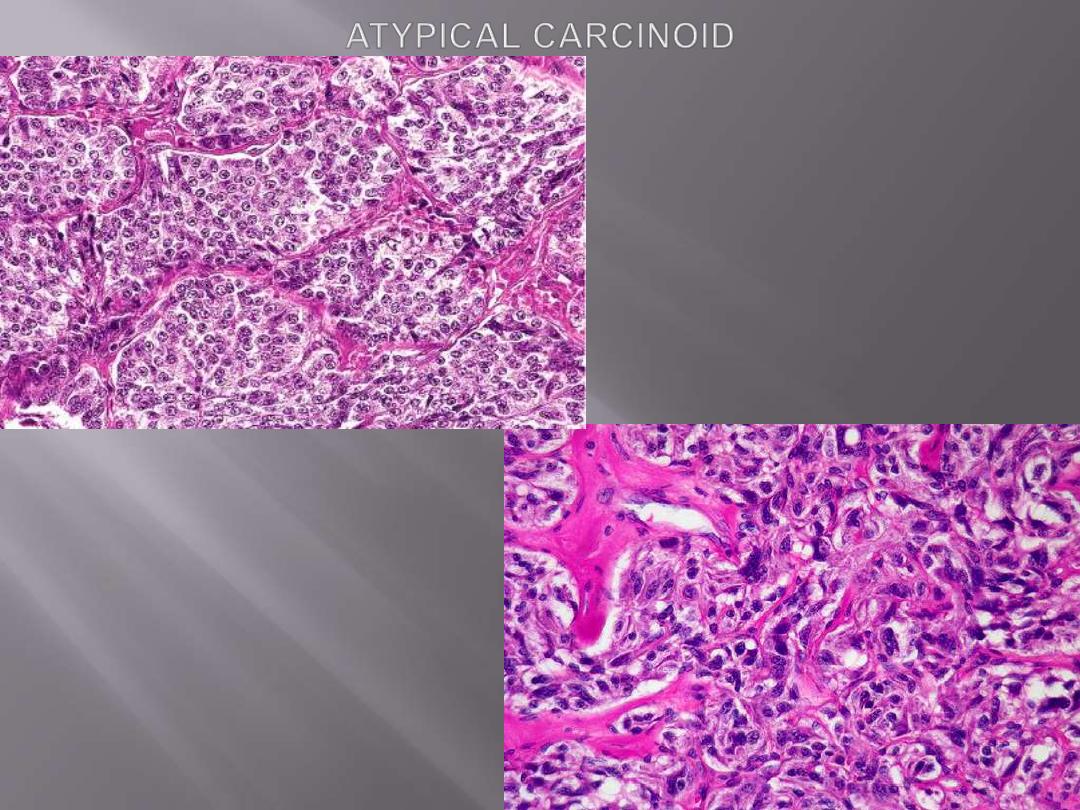

1. Having higher mitotic rate, cytologic pleomorphism , and focal necrosis

2. Having a higher incidence of lymph node and distant metastasis.

Typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, and small-cell

carcinoma can be considered to represent a continuum

of increasing histologic aggressiveness and malignant

potential

within

the

spectrum

of

pulmonary

neuroendocrine neoplasms.

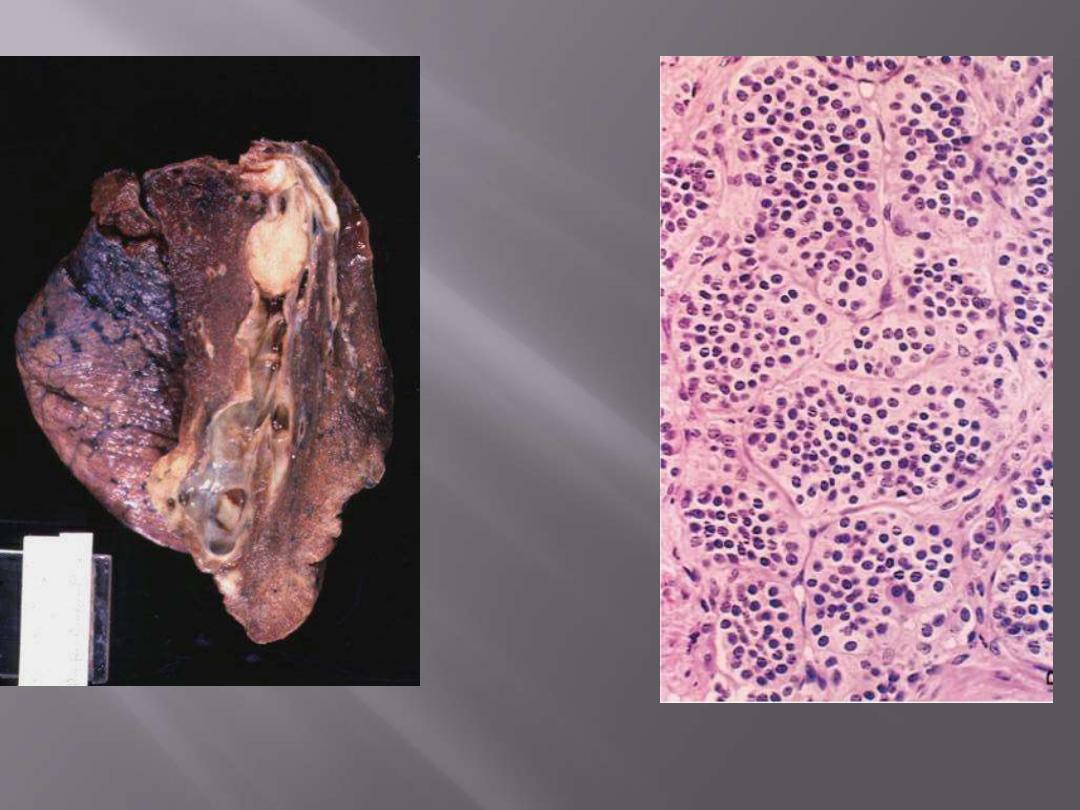

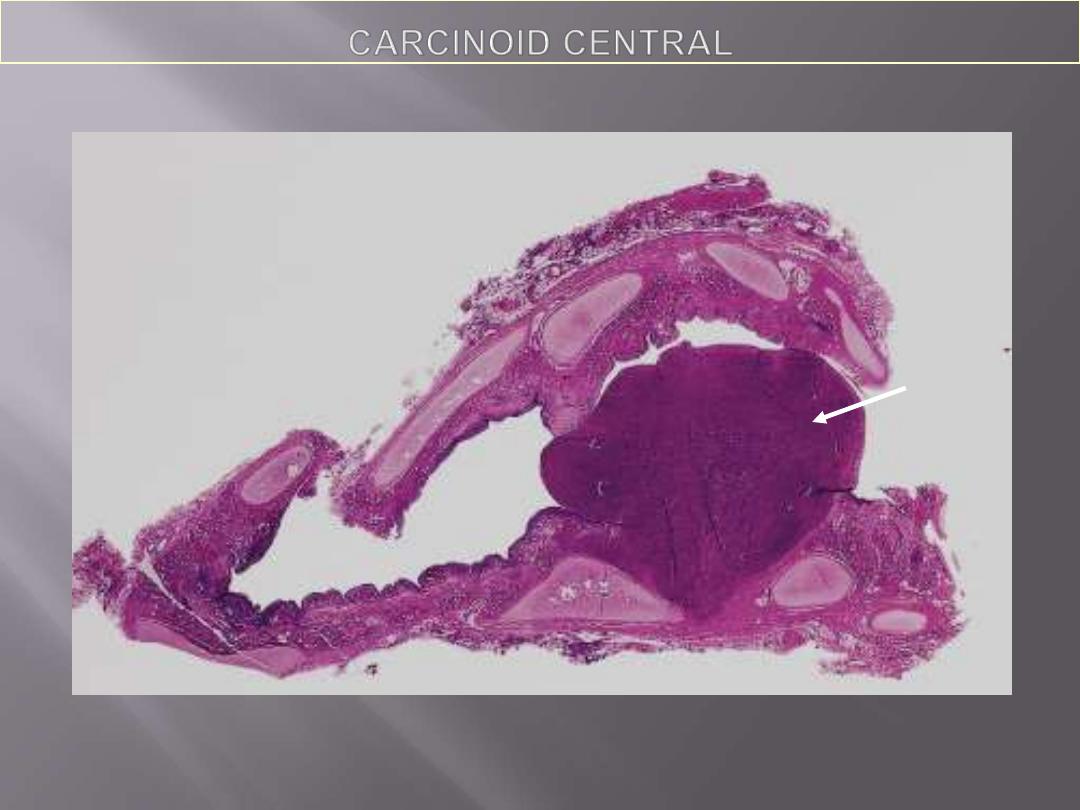

A, Bronchial Carcinoid Tumor: Yellow intrabronchial mass (lower) has resulted in obstructive

bronchiectasis

B, Histologic appearance demonstrating trabecular arrangement of small, rounded, uniform cells.

Bronchial carcinoid

Whole mount of carcinoid tumor showing polypoid endobronchial growth.

The tumor is composed of nests of uniform cells that have regular round nuclei & absent or rare

mitoses

There is typical nesting of marked

pleomorphic cells. mitotic activity, and

necrosis are also present elsewhere.

Course & prognosis

Most clinical features are related to their intraluminal

growth (cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent bronchial and

pulmonary infections).

Some are asymptomatic and discovered by chance on

imaging studies. Only rarely do they induce the

carcinoid syndrome,

characterized by intermittent

attacks of diarrhea, flushing, and cyanosis.

The reported

10-year

survival rates for typical

carcinoids are

85%

, but these drop to

35%

for atypical

carcinoids.

Only 5% of patients with SCLC are alive at 10 years.

THE PLEURA

Pleural Effusion

refers to the presence of fluid in the pleural space. The fluid

can be either a transudate or an exudate. A transudate is termed

hydrothorax

, which

is mostly due to CHF. An exudates is characterized by protein content of 3.0 gm/dl

or more and, often, inflammatory cells. The four

principal causes of pleural

exudate are

1. Microbial invasion; either direct extension of a pulmonary infection or blood-

borne seeding (suppurative exudates or empyema)

2. Cancer (lung carcinoma, metastatic cancers to the lung or pleural

mesothelioma

3. Pulmonary infarction

4. Viral pleuritis

Less common causes include SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, uremia.

Cancer should be suspected as the underlying cause of an exudative effusion in

any patient older than the age of 40, particularly when there is no febrile

illness, no pain, and a negative tuberculin test result. These effusions

characteristically are large and frequently bloody (hemorrhagic). Cytologic

examination may reveal malignant and inflammatory cells.

Pneumothorax

refers to air in the pleural sac. It may occur in young,

healthy adults, usually men without any known pulmonary disease

(spontaneous pneumothorax),

or as a result of some thoracic (e.g. a fractured

rib) or lung disorder (secondary pneumothorax).

Secondary pneumothorax

occurs with rupture of any pulmonary lesion

situated close to the pleural surface that allows inspired air to gain access to the

pleural cavity. Such pulmonary lesions include

emphysema, lung abscess,

tuberculosis, carcinoma, etc. Supportive mechanical ventilation with high

pressure may also trigger secondary pneumothorax.

A serious complication may occur through a ball-valve leak that creates a

tension pneumothorax.

This shifts the mediastinum, which may be

followed by impairment of the pulmonary circulation that may be fatal.

With prolonged collapse, the lung becomes vulnerable to infection, as does the

pleural cavity.

Empyema

is

thus

an

important

complication

of

pneumothorax

(pyopneumothorax).

Hemothorax

is the collection of whole blood (in contrast to

bloody effusion) in the pleural cavity, is a complication of a

ruptured intrathoracic aortic aneurysm that is almost always

fatal.

Chylothorax

is a pleural collection of a milky lymphatic

fluid containing microglobules of lipid. It implies obstruction

of the major lymph ducts, usually by an intrathoracic cancer

(e.g., a primary or secondary mediastinal neoplasm, such as

a lymphoma).

Malignant Mesothelioma

is a rare cancer of mesothelial cells, usually arising in the

parietal or visceral pleura.

It also occurs, much less commonly, in the peritoneum and

pericardium.

In the USA approximately 50% of individuals with this

cancer have a history of exposure to

asbestos.

The latent period for developing malignant mesotheliomas

is long

(25 to 40 years)

after initial asbestos exposure.

The combination of cigarette smoking and asbestos

exposure greatly increases the risk of bronchogenic

carcinoma, but it does not increase the risk of developing

malignant mesotheliomas.

Gross features

These tumors begin in a localized area but in the

course of time spread widely.

At autopsy, the affected lung is typically

ensheathed by a yellow-white, firm layer of tumor

that obliterates the pleural space

The neoplasm may directly invade the thoracic

wall or the subpleural lung tissue.

M/67. This vertical slice of the right lung shows the

manner in which a pleural mesothelioma causes

thickening of the pleura and encases the whole

lung and mediastinum.

Malignant mesothelioma pleura

Malignant mesothelioma

Thick, firm, white, pleural tumor that ensheaths the

lung. Nodular invasion into the lung parenchyma is also

evident.

Note the thick, firm, white, pleural tumor that ensheaths this bisected lung.

Malignant mesothelioma

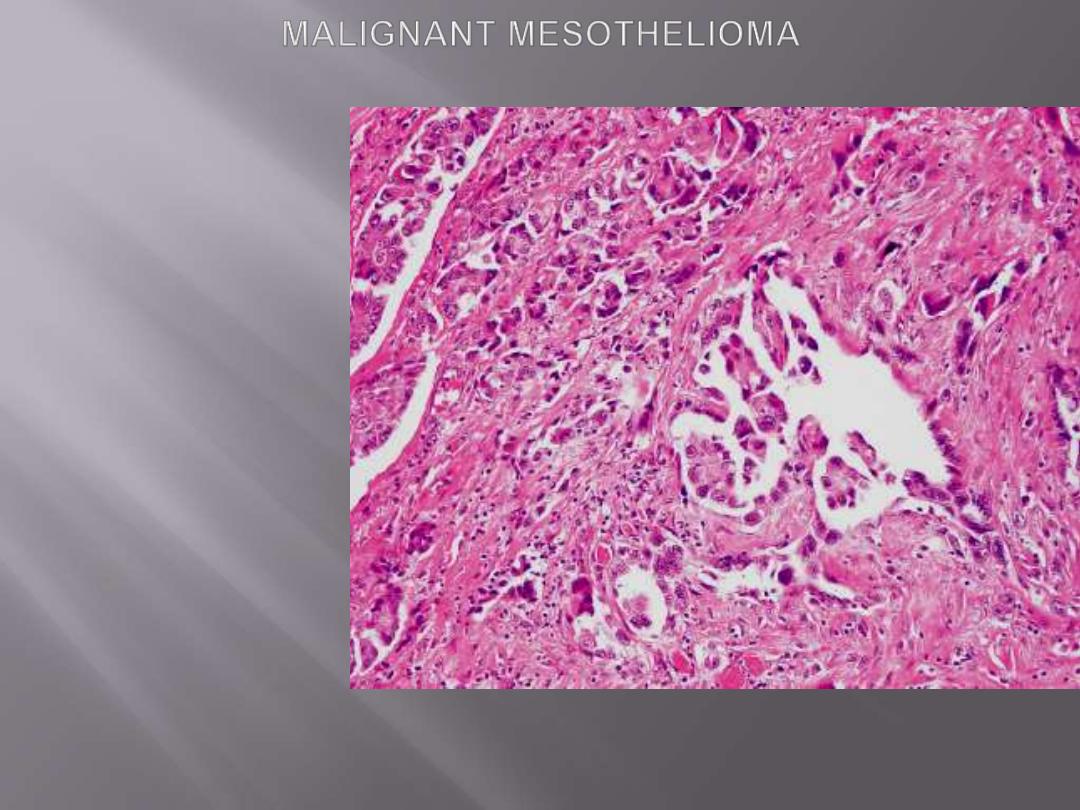

Microscopic features

Mesotheliomas conform to one of three patterns:

1. Epithelial,

in which cuboidal cells line tubular and

microcystic spaces, into which small papillary buds

project.

2. Sarcomatoid,

in which spindled cells grow in sheets

3. Biphasic,

having both sarcomatoid and epithelial

areas.

Malignant mesothelioma with papillary formations and desmoplastic stromal reaction.