PATHOLOGY OF THE REPIRATORY

SYSTEM

part I

OBJECTIVES:

By the end of these series of lecture on respiratory system pathology the students

would be able to:

1- define the pathogenesis and the pathological features of the most common tumor

like and tumor (benign and malignant) conditions of the upper respiratory tract

including: allergic nasal polyp, angiofibroma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, laryngeal

tumors including: vocal cord nodule, laryngeal papilloma and laryngeal carcinoma.

2- describe atelectasis of the lung and its classification.

3- define adult respiratory distress syndrome and its causes and pathological features.

4- define (the pathogenesis and the pathological features) and list obstructive

pulmonary disease: asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis and broncheactasis.

5- describe the pathogenesis, types and pathological features of diffuse interstitial

lung diseases.

6- define and list the granulomatous lung diseases.

7- identify the pathogenesis and pathological features of pulmonary infections.

8- outline the pathogenesis and the pathological features of pulmonary tuberculosis.

9- list and classify the most important lung tumors describing the pathogenesis and

pathological features, with clinical presentations including paraneoplastic syndrome

descriptions.

10- define diseases of the pluera and list the most common neoplasms of the pleura.

THE UPPER RESPIRATORY

TRACT

Allergic nasal polyp

Not true neoplasms. They are associated with inflammation

and allergy. Generally, they are multiple (bunch of grapes),

and nearly always bilateral.

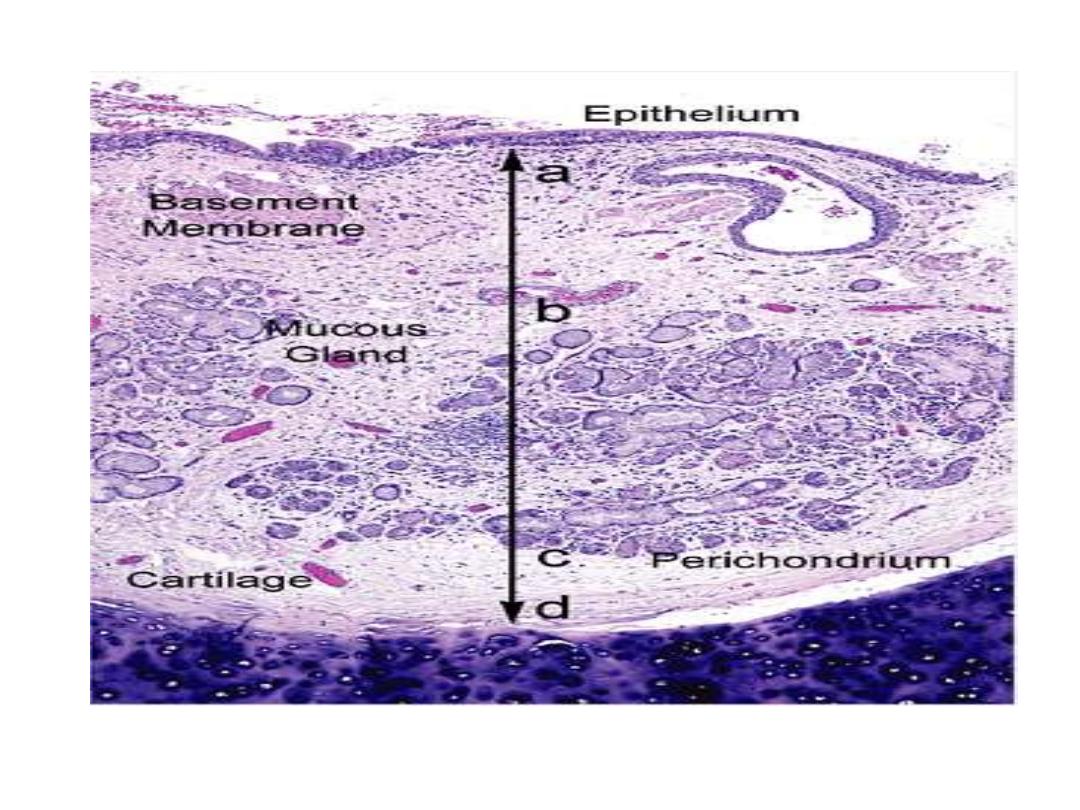

Microscopically:

composed of loose mucoid stroma and mucous glands

covered by respiratory epithelium which often shows foci of

squamous metaplasia. They are infiltrated by lymphocytes,

plasma cells, mast cells, neureophils and eosinophils.

Benign tumors of the Nose and Nasal Cavity:

ANGIOFIBROMA

It occurs almost exclusively in males.

It is androgen dependent.

It presents as polypoidal mass that bleeds severely on

manipulation.

Microscopically:

Composed of matrix of blood vessels and fibrous tissue stroma

which may be loose and edematous or dense acellular and highly

collagenized.

The vessels range from capillary size which are particularly

common at the growing edge of the tumor, they have got plump

endothelial cells.

Larger venous size vessels are located at the base of the lesion.

Malignant Tumors:

NASOPHARYNGEAL CARCINOMA

This rare neoplasm has a strong epidemiologic links to

EBV

& a high

frequency in

China

.

These facts raise the possibility of

viral oncogenesis

on a background of

genetic susceptibility.

The cancers are either

squamous cell carcinoma

(keratinizing or

nonkeratinizing) or

undifferentiated carcinoma

. The latter is the most

common and the one most closely linked with EBV.

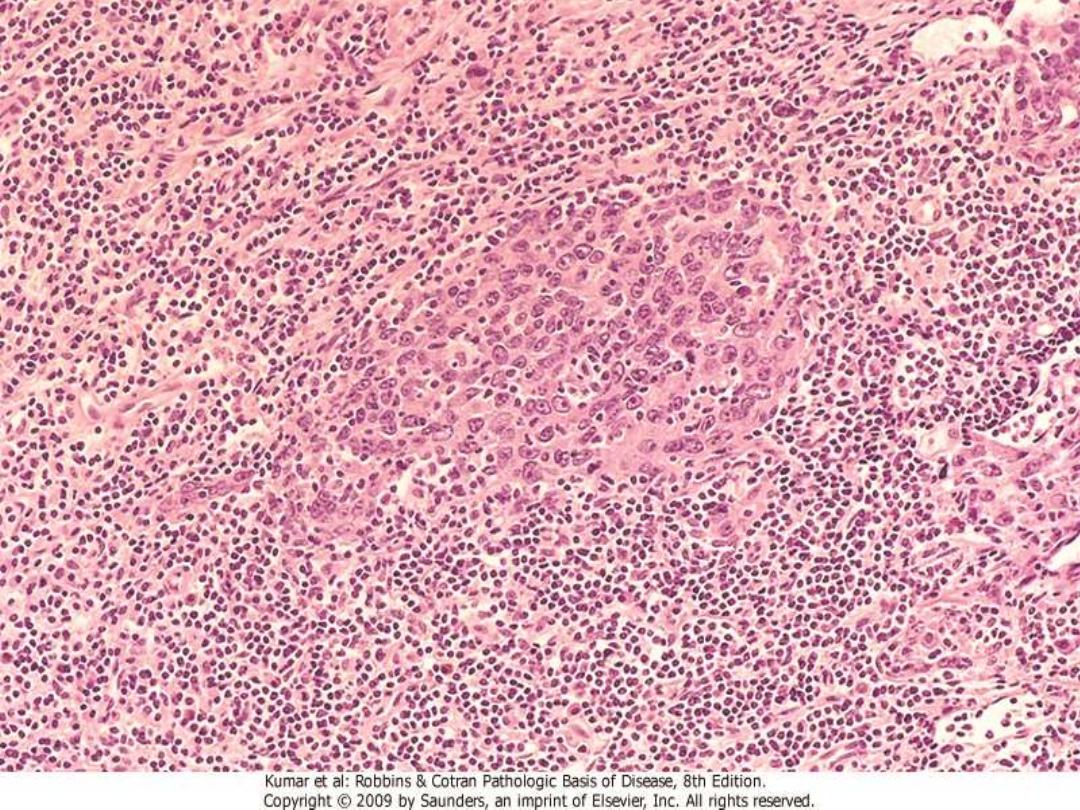

In nasopharyngeal carcinomas a striking infiltration of mature

lymphocytes can often be seen. These neoplasms are therefore referred

to as

"lymphoepitheliomas,"

although the lymphocytes are not part of

the neoplastic process.

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas invade locally, spread to cervical lymph

nodes, and then metastasize to distant sites.

They are, however,

radiosensitive

, and 5-year survival rates of 50% are

reported for even advanced cancers.

LARYNGEAL TUMORS

Benign Lesions

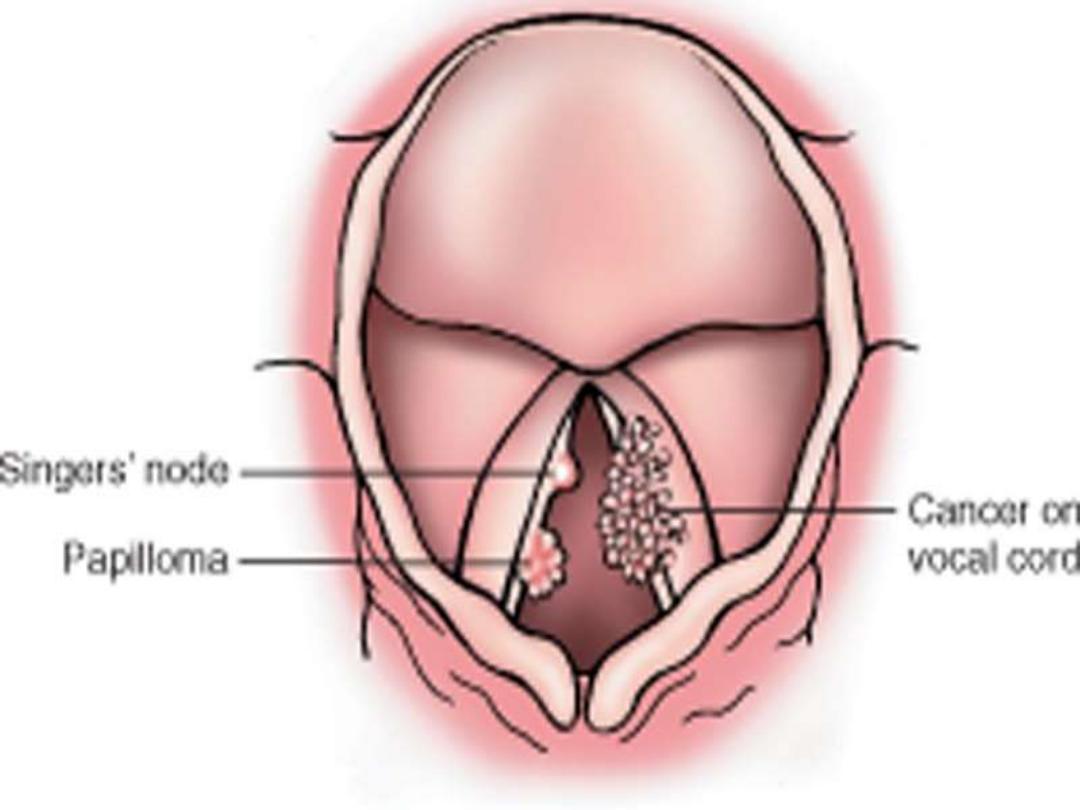

Vocal cord nodules ("polyps")

are smooth protrusions (usually less than

0.5 cm in diameter) located, most often, on

the true vocal cords

. The nodules

are composed of fibrous tissue and covered by stratified squamous mucosa.

These lesions occur chiefly in

heavy smokers or singers (singer's nodes)

,

suggesting that they are the result of chronic irritation or voice abuse.

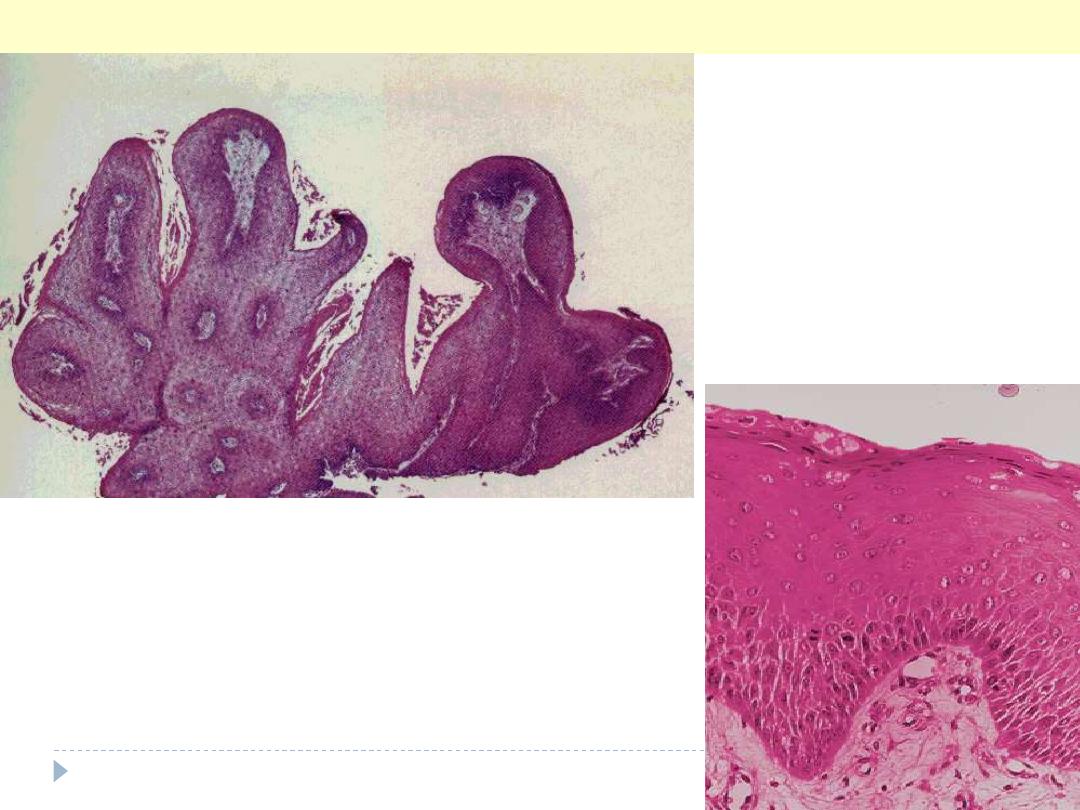

Laryngeal papilloma (squamous papilloma)

of the larynx is a benign

neoplasm, usually on the

true vocal cords

, that forms a soft, raspberry-like

excrescence rarely more than 1 cm in diameter.

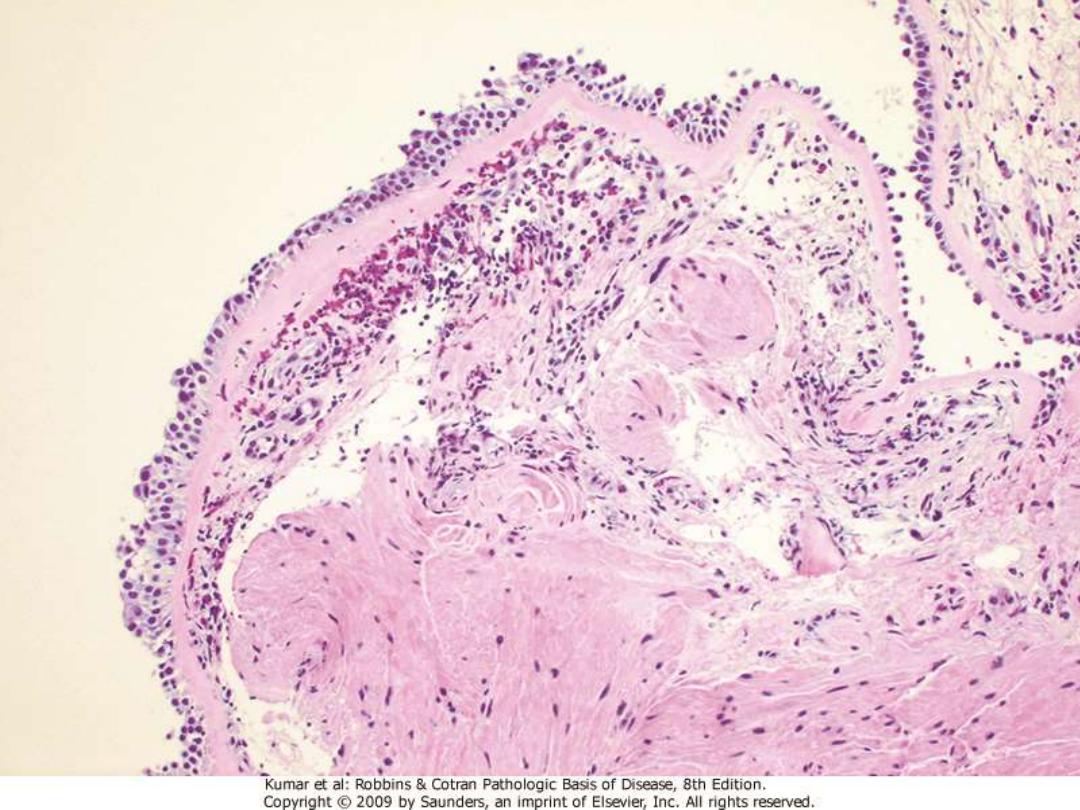

Microscopically

, it consists of

multiple, slender, finger-like projections supported by central fibrovascular

cores and covered by benign, stratified squamous epithelium.

Papillomas are usually single in adults but are often multiple in children

, in

whom they are referred to as

recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP),

since

they typically tend to recur after excision. These lesions are caused by

human

papillomavirus (HPV) types 6 and 11,

do not become malignant, and often

spontaneously regress at puberty.

A 28-year-old man who is a singer/songwriter has been experiencing hard

times for the past 3 years. He has played at a couple of clubs a night to

earn enough to avoid homelessness. He comes to the free clinic because he

has noticed that his voice quality has become progressively hoarser over

the past year. On physical examination: There are no palpable masses in

the head and neck area. He does not have a cough or significant sputum

production, but he has been advised on previous visits to give up smoking.

Which of the following is most likely to produce these findings?

(A) Croup

(B) Epiglottitis

(C) Reactive nodule

(D) Squamous cell carcinoma

(E) Squamous papillomatosis

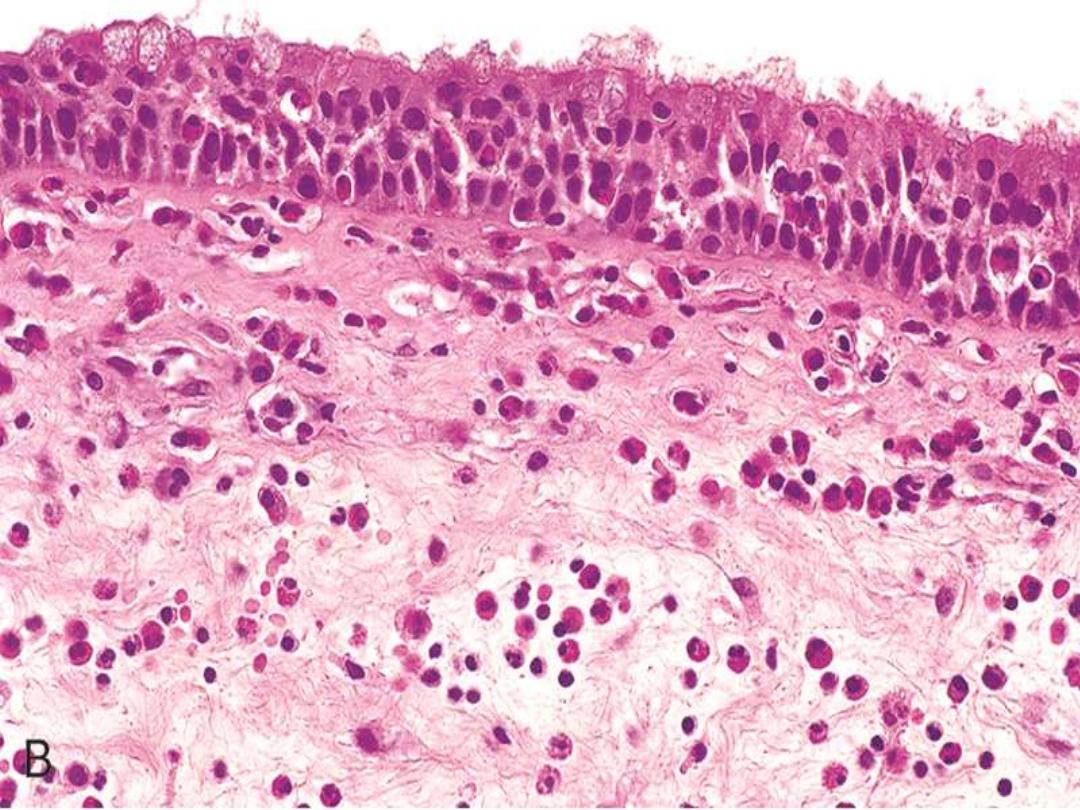

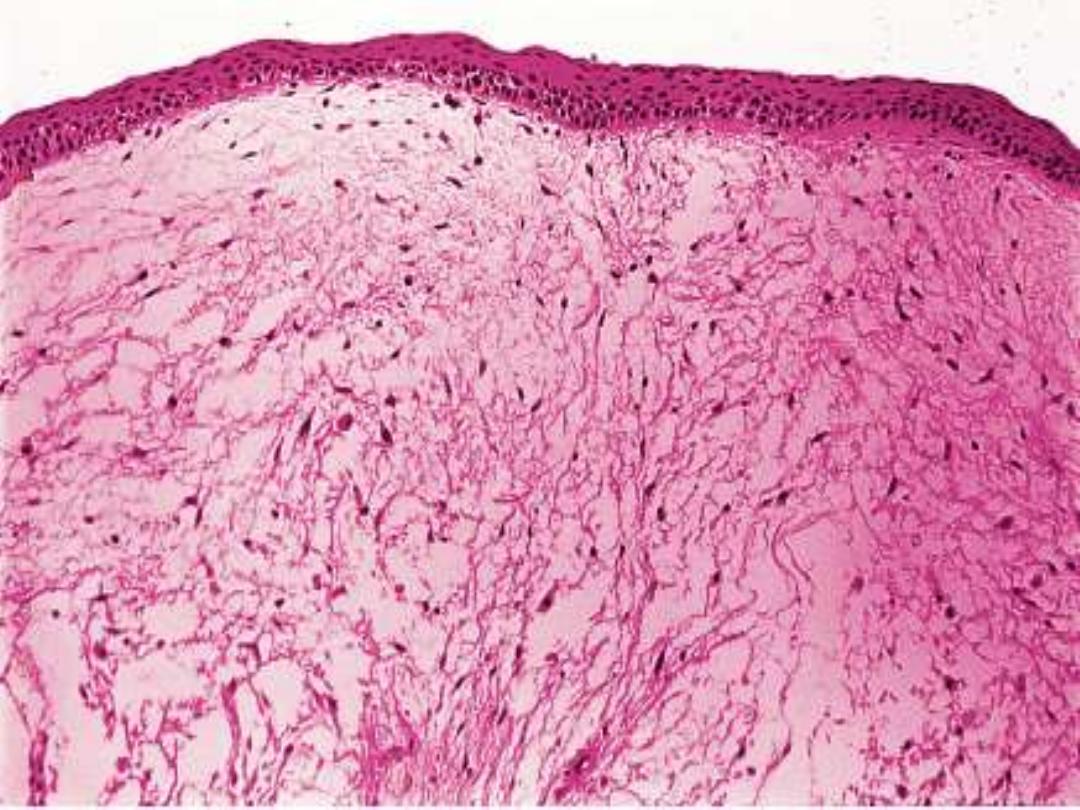

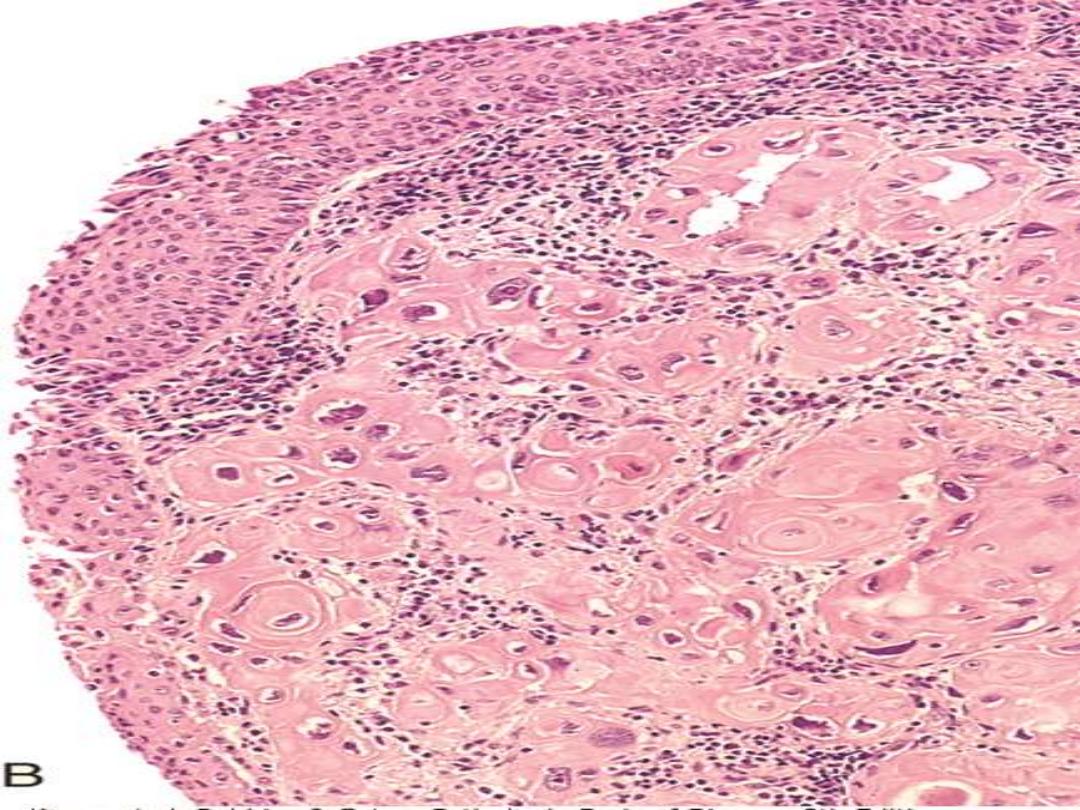

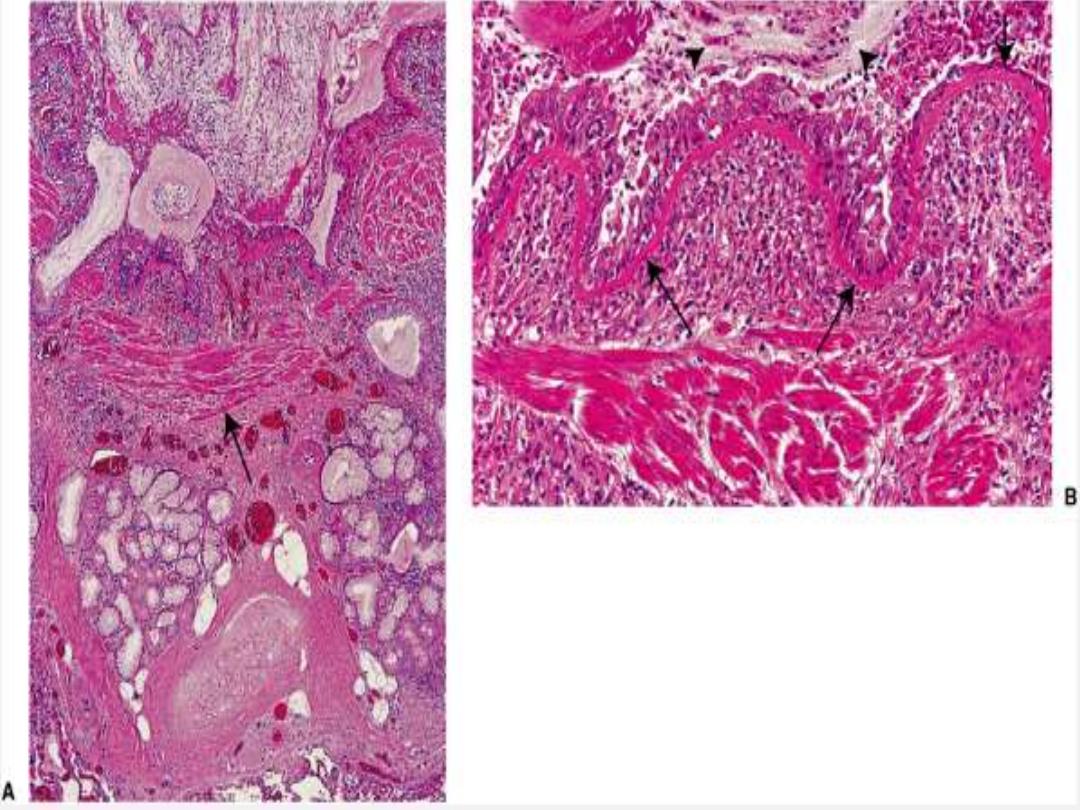

This multilayered benign-looking squamous epithelium is

arranged in a finger-like projections, each having a core of

vascularized connective tissue. The Rt. Photo is a higher power

showing the squamous epithelium cover of one of the papillae.

Squamous cell papilloma larynx

Malignant Lesions

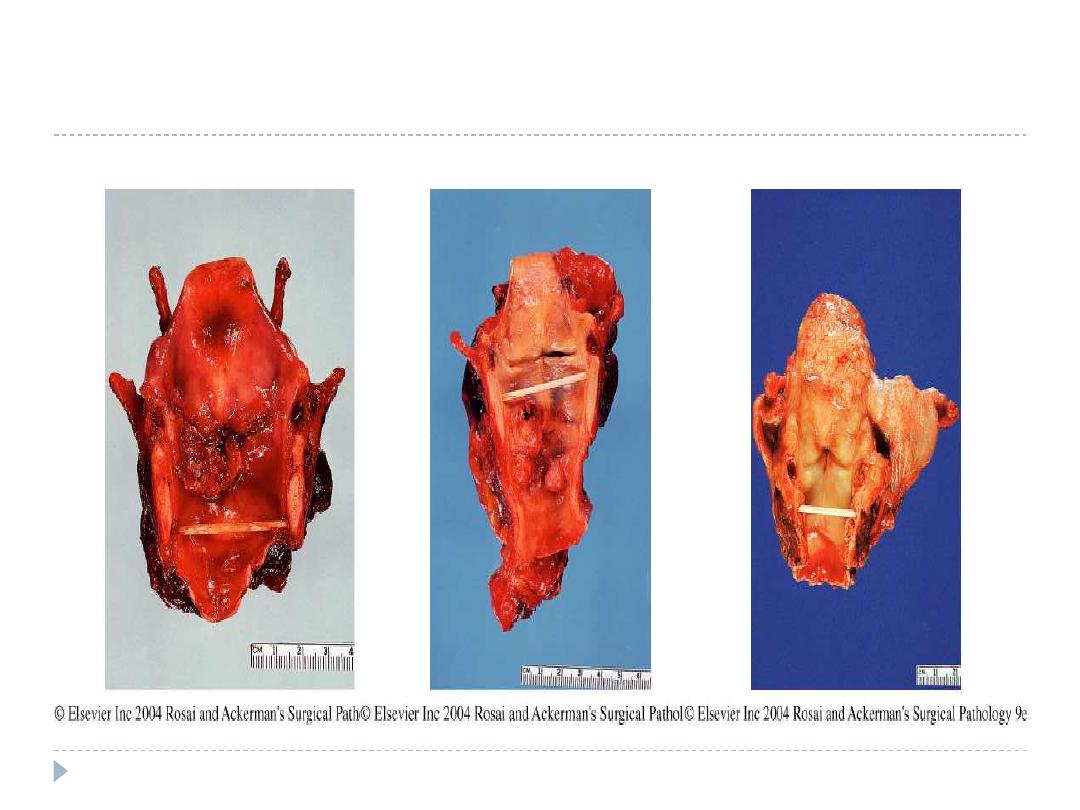

Carcinoma of the Larynx

Carcinoma of the larynx most commonly occurs after age

40 years

and is more

common in men

(7: 1)

than in women.

Nearly all cases occur in

smokers,

and

alcohol and asbestos

exposure may also

play roles.

The vast majority (95%) are

squamous cell carcinomas.

The tumor develops mostly on the

vocal cords (glottic tumors),

but it may arise

above the cords

(supraglottic)

or below the cords

(subglottic).

They begin as

in situ lesions

that later appear as pearly gray, wrinkled plaques

on the mucosal surface, ultimately ulcerating and fungating.

As expected with lesions arising from recurrent exposure to environmental

carcinogens, adjacent mucosa may demonstrate squamous cell hyperplasia with

foci of dysplasia, or even carcinoma in situ.

Clinically there is persistent

hoarseness.

Supraglottic cancers have a worse prognosis than glottic tumors because of their

earlier metastasis to regional (cervical) lymph nodes. The subglottic tumors, like

the supraglottic ones, tend to remain clinically silent, & thus usually present as

advanced disease.

With surgery, radiation, or combined therapeutic treatments, only one third die

of the disease.

The usual cause of death is infection of the distal respiratory passages or

widespread metastases and cachexia.

Transglottic Infraglottic Supraglottic

A 70-year-old man who has experienced increasing

hoarseness for almost 6 months has recently had an episode

of hemoptysis. On physical examination, no lesions are noted

in the nasal or oral cavity. There is a firm, nontender anterior

cervical lymph node. The lesion shown in the figure is

identified by endoscopy. The patient undergoes biopsy,

followed by laryngectomy and neck dissection. Which of the

following etiologic factors most likely played the greatest role

in the

development of this lesion?

(A) Human papillomavirus infection

(B) Type I hypersensitivity

(C) Smoking tobacco

(D) Repeated bouts of aspiration

(E) Epstein-Barr virus infection

THE LUNG

ATELECTASIS (COLLAPSE)

is loss of lung volume caused by inadequate expansion of

airspaces; this leads to shunting of inadequately oxygenated blood

from pulmonary arteries into veins, thus giving rise to hypoxia.

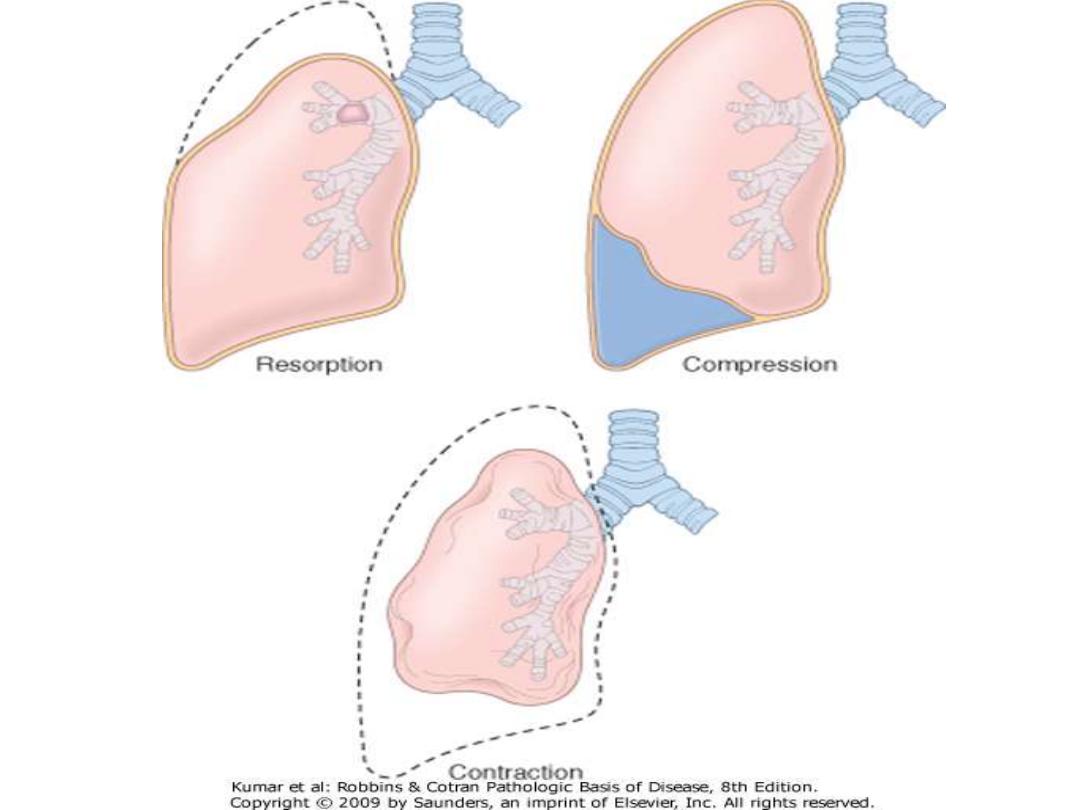

Pathogenetically atelectasis is classified into three forms

1.

Resorption atelectasis

complicating obstruction.

The air already present distally gradually becomes absorbed, and alveolar

collapse follows.

Depending on the level of airway obstruction, an entire lung, a complete

lobe, or a segment may be involved.

A mucous or muco-purulent plug is the most common cause of such

obstruction for

e.g. following surgical operations or bronchial asthma,

bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, or the aspiration of foreign bodies,

particularly in children.

2. Compression atelectasis

is usually due to mechanical compression of the lung by pleural

distension as in pleural effusion (congestive heart failure) or

pneumothorax.

Basal atelectasis

is another example & is due to elevated diaphragm as

that occurs in bedridden patients, in those with ascites, and during and

after surgery.

3. Contraction atelectasis

occurs in the presence of focal or generalized pulmonary fibrosis or

pleural fibrosis; in these situations there is interference with expansion

and an increase in elastic recoil during expiration.

Atelectasis (except contraction type) is reversible and should be treated

quickly to prevent hypoxemia and infection of the collapsed lung.

A 7-year-old boy accidentally inhales a small peanut,

which lodges in one of his bronchi. A chest x-ray

reveals the mediastinum to be shifted toward the

side of the obstruction. Which of the following

pulmonary abnormalities is most likely present in

this boy?

a. Absorptive atelectasis

b. Compression atelectasis

c. Contraction atelectasis

d. Patchy atelectasis

e. Hyaline membrane disease

ADULT RESPIRATORY DISTRESS

SYNDROME (ARDS)

(previously “Shock lung”) is “progressive

respiratory insufficiency caused by diffuse alveolar damage”

The clinical setting associated with ARDS include

A. Respiratory

1. Diffuse infections (viral, bacterial)

2. Aspiration

3. Inhalation (toxic gases, near drowning)

4. O

2

therapy

B. Non-respiratory

1. Sepsis (septic shock)

2. Trauma (with hypotension)

3. Burns

4. Pancreatitis

5. Ingested toxins (e.g. paraquat)

There is an acute onset of dyspnea, hypoxemia (refractory to O

2

therapy), and

radiographic bilateral pulmonary infiltrates (noncardiogenic pulmonary edema).

The condition may progress to multisystem organ failure.

Pathogenesis

In ARDS there is damage to alveolar capillary membrane by endothelial

&/or epithelial injury. This leads to three consequences

1. Increased vascular permeability (endothelial damage)

2. Loss of diffusion capacity of the gases

3. Widespread surfactant deficiency (damage to type II pneumocytes).

Nuclear factor κB,

is suspected of tilting the balance in favor of pro-

inflammatory rather than anti-inflammatory mediators, which causes

the endothelial damage.

This leads to fluid accumulation.

Following the insult, there is increased synthesis of a potent neutrophil

chemotactic and activating agent

IL-8 & TNF

by pulmonary

macrophages.

The recruited, activated neutrophils release oxidants, proteases, etc.

that cause damage to the alveolar epithelium leading to loss of

surfactant that interferes with alveolar expansion.

Gross features:

in the acute phase the lungs are dark red, airless, and heavy.

Microscopic features:

The histologic reflection of ARDS in the lungs is known as

diffuse alveolar damage.

Early stage is characterized by

Capillary congestion and stuffing by neutrophils

Necrosis of alveolar epithelial cells

Interstitial and intra-alveolar edema and sometimes hemorrhage

The presence of

hyaline membranes is characteristic

.

They particularly line the distended alveolar ducts & consist of fibrin admixed

with necrotic epithelial cells.

Overall, the picture is very similar to that seen in

respiratory distress syndrome

in the newborn.

Organizing stage is characterized by

Marked regenerative proliferation of type II pneumocytes

Organization of the fibrin exudates.

This eventuates in intra-alveolar fibrosis.

Marked fibrotic thickening of the alveolar septa.

The prognosis of ARDS

is gloomy and

mortality rates are around 60%

despite improvements in

supportive therapy.

However, in most patients who survive the acute insult normal

respiratory function returns.

Alternatively,

diffuse interstitial fibrosis occurs with permanent

impairment of respiratory function.

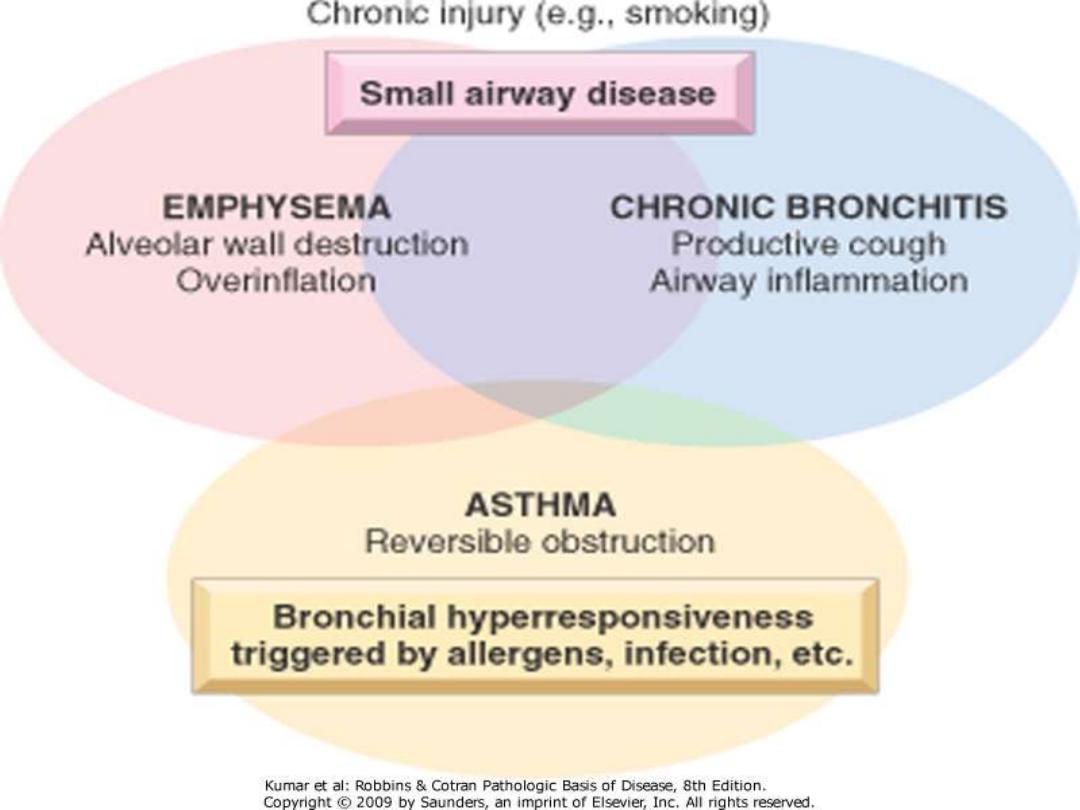

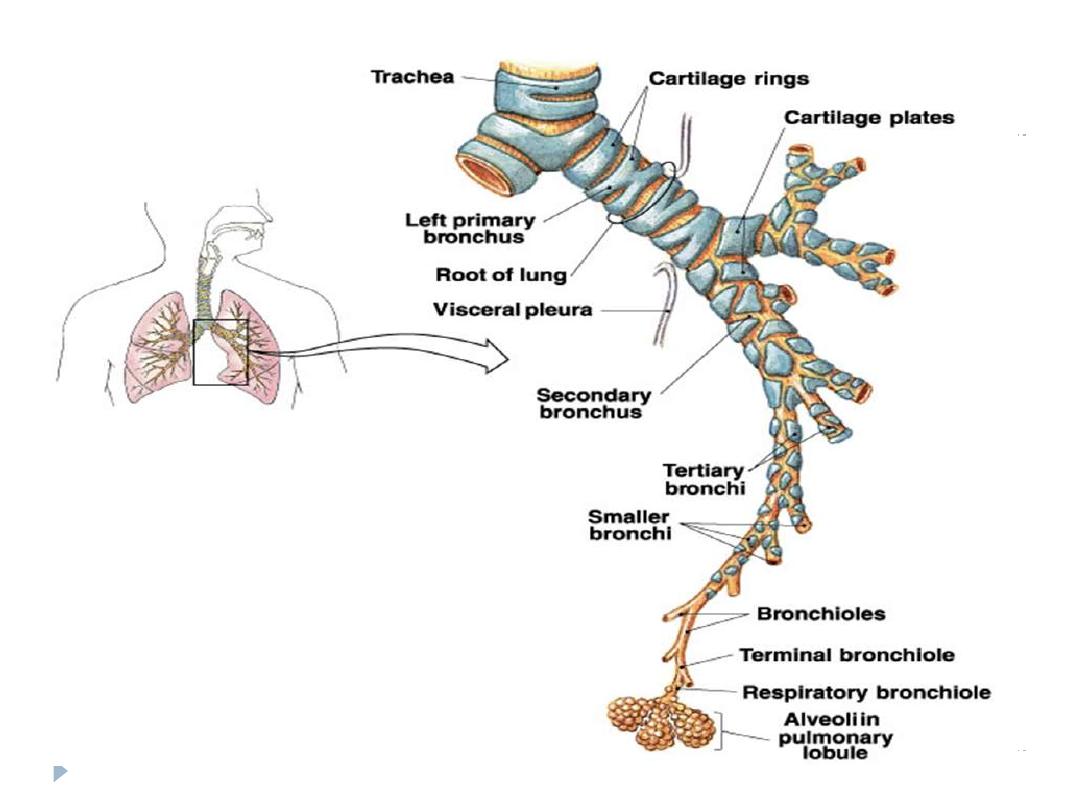

OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

Under this heading come four entities

1. Emphysema

2. Chronic bronchitis

3. Asthma

4. Bronchiectasis

Although chronic bronchitis may exist without emphysema, and pure

emphysema may occur (with inherited α

1

-antitrypsin deficiency), the two

diseases usually coexist.

This is because long-term cigarette smoking is a common underlying

agent in both disorders.

Emphysema and chronic bronchitis are often clinically grouped together

under the term

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),

which is

one of the leading causes of death.

The irreversibility of airflow obstruction of COPD distinguishes it from

asthma (reversible obstruction)

EMPHYSEMA

is defined as

"abnormal permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the

terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls without

obvious fibrosis".

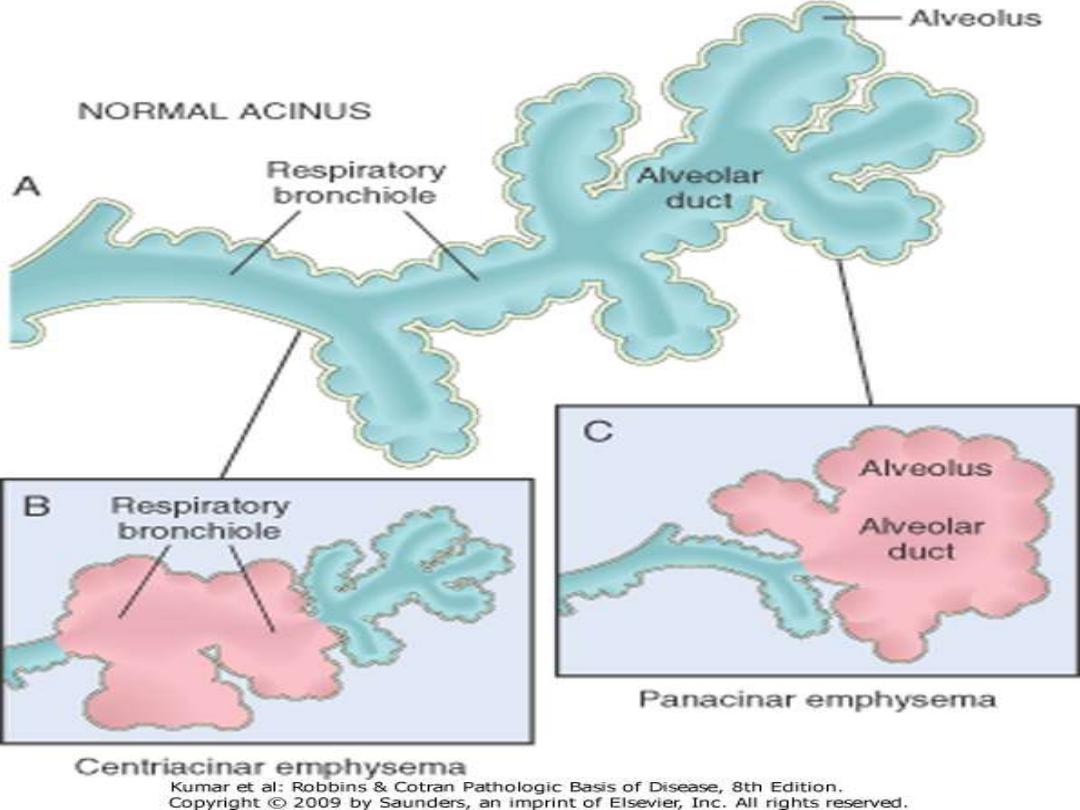

Classification of Emphysema

is according to its anatomic distribution

within the lobule; the acinus is the structure distal to terminal bronchioles,

and a cluster of 3 to 5 acini is called a lobule. There are four major types of

emphysema:

1. Centriacinar

2. Panacinar

3. Distal acinar

4. Irregular

Only the first two cause clinically significant airway obstruction, with

centriacinar emphysema being about 20 times more common than

panacinar disease.

Centriacinar (Centrilobular) Emphysema:

the central parts of the

acini i.e.

the respiratory bronchioles

are affected, while distal alveoli are

spared. The lesions are more common and severe in the

upper lobes

.

This

type is most commonly associated with cigarette smoking.

Panacinar (Panlobular) Emphysema:

the acini are uniformly

enlarged from the level of the respiratory bronchiole to the terminal blind

alveoli . It tends to occur more commonly in the

lower lobes

and is

the type

that occurs in α

1

-antitrypsin deficiency.

Distal Acinar (Paraseptal) Emphysema:

the distal part of the acinus

is primarily involved especially adjacent to the pleura and the lobular

connective tissue septa. Characteristically, there are

multiple, adjacent,

enlarged airspaces up to 2 cm or more in diameter, sometimes forming

cystic structures referred to as bullae.

This type of emphysema probably

underlies many of the cases of spontaneous pneumothorax in young adults.

Irregular Emphysema:

the acinus is irregularly involved; it is

associated with

scarring.

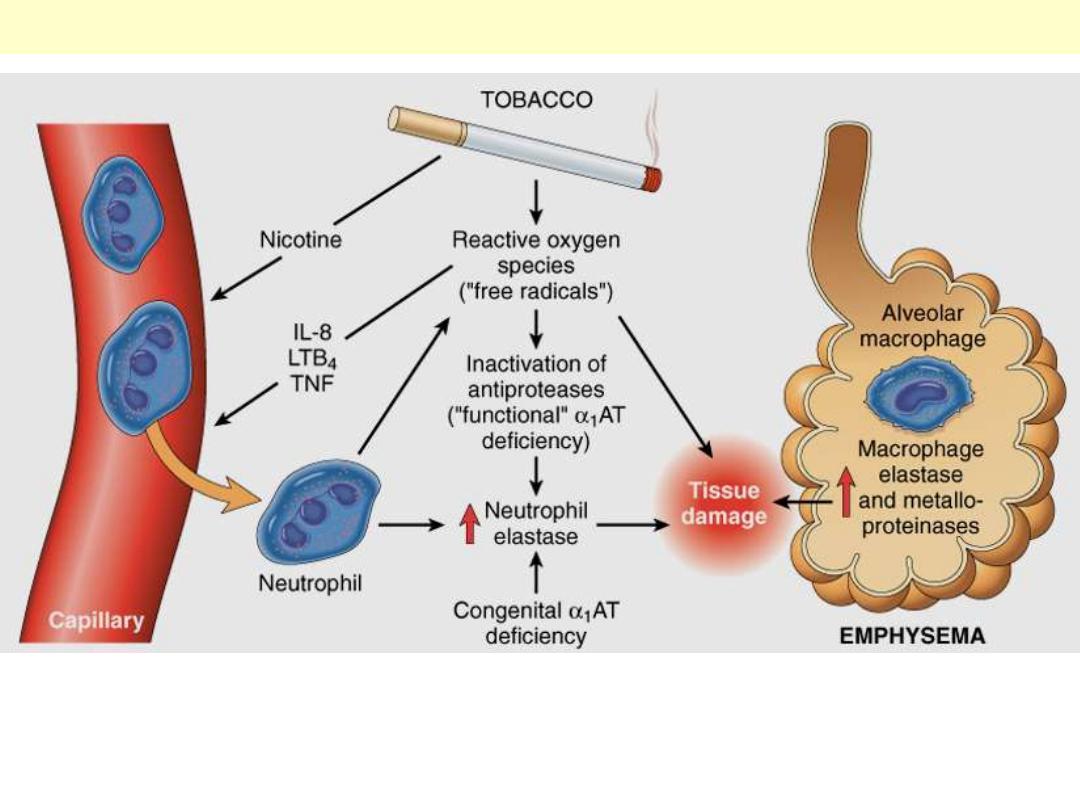

Pathogenesis of centriacinar & panacinar forms of

emphysema

These are thought to arise as a result of

imbalances of

protease-antiprotease and oxidant-antioxidant .

The protease-antiprotease imbalance hypothesis is

supported by the enhanced tendency of emphysema

development in patients with

genetic α1-antitrypsin

deficiency, which is aggrvated by smoking.

α1-Antitrypsin, is a major inhibitor of proteases

(particularly elastase) secreted by neutrophils during

inflammation.

Emphysema seems to result from the destructive effect of

high protease activity in subjects with low antiprotease

action.

Smoking seems to play a decisive role in the pathogenesis of

emphysema

1.

It causes accumulation of neutrophils & macrophages within the

alveoli through its

direct chemoattractant effects

and through the

reactive oxygen species contained in it. These activate the

transcription factor

NF-κB

, which switches on genes that encode

TNF

and IL-8.

These, in turn, attract and activate more neutrophils. Accumulated

active neutrophils release their granules, which are rich in a variety of

proteases (

elastase, proteinase, etc

.) that result in tissue damage.

2. Smoking also

enhances elastase activity in macrophages;

this elastase is

not inhibited by α

1

-antitrypsin; additionally, it can digest this

antiprotease.

3. Tobacco smoke contains

abundant reactive oxygen free radicals,

which

deplete the antioxidant mechanisms, thereby inciting tissue damage.

A secondary consequence of oxidative injury is inactivation of native

antiproteases, resulting in "functional" α

1

-antitrypsin deficiency even in

patients without enzyme deficiency

The protease-antiprotease imbalance and oxidant-antioxidant imbalance are additive in their effects

and contribute to tissue damage. α1-Antitrypsin (α1AT) deficiency can be either congenital or

"functional" as a result of oxidative inactivation. See text for details. IL-8, interleukin 8; LTB4,

leukotriene B4; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Pathogenesis of emphysema

Gross features

The diagnosis and classification of emphysema depend on the gross

appearance of the lung.

Panacinar emphysema produces pale, voluminous lungs that obscure

the heart at autopsy.

In centriacinar emphysema the lungs are less voluminous and deeper

pink. Generally, in this type the upper two-thirds of the lungs are more

severely affected.

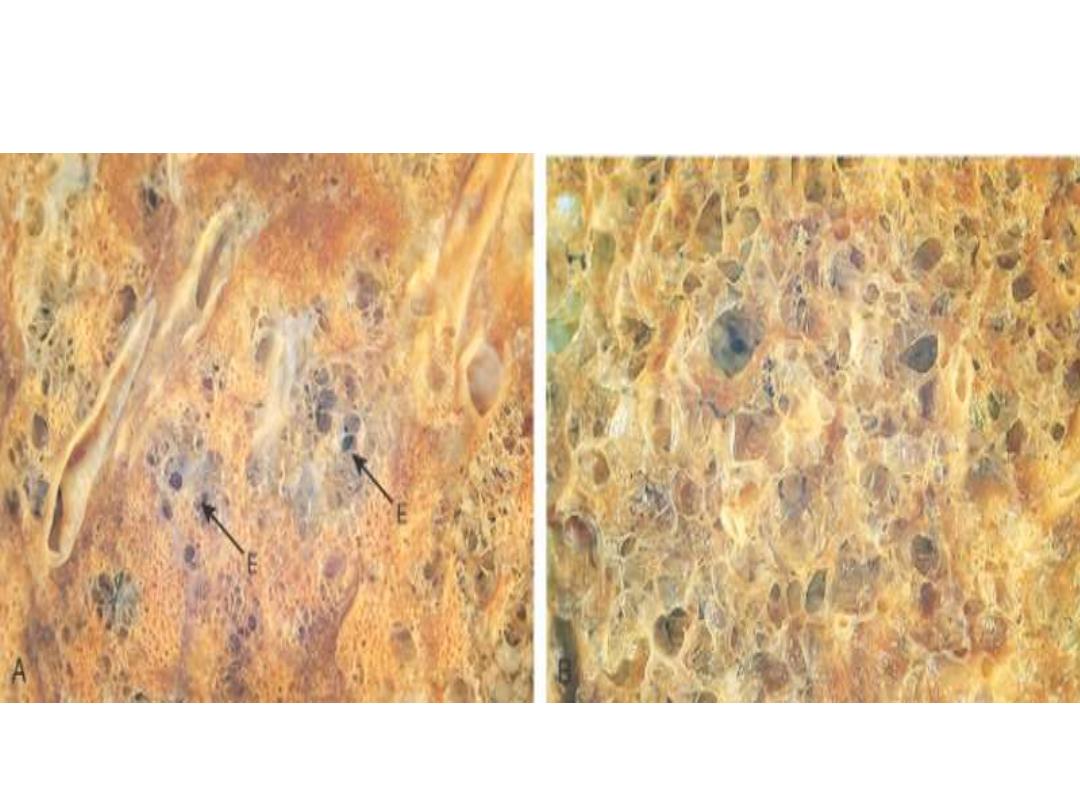

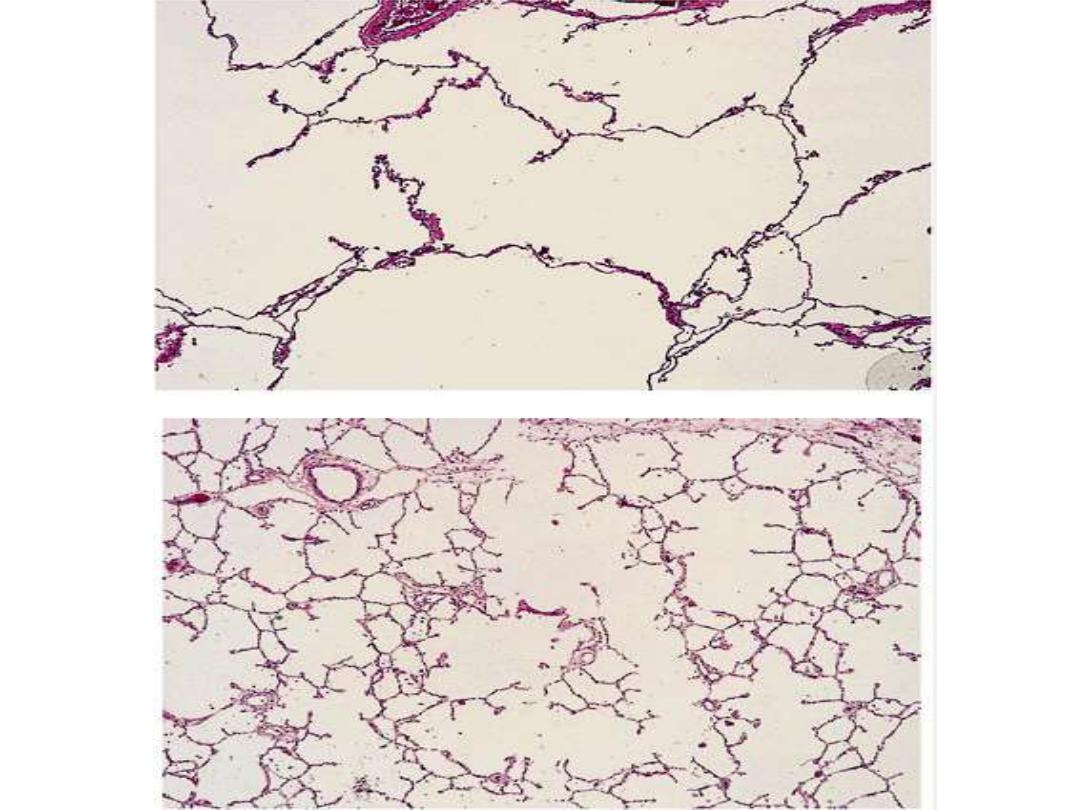

Microscopic features

There is thinning and destruction of alveolar walls.

With advanced disease, adjacent alveoli coalesce, creating large

airspaces.

The capillaries within alveolar walls are reduced in number due to

stretching.

There is severe diffuse involvement of the acini; the whole acinus is markedly

dilated.

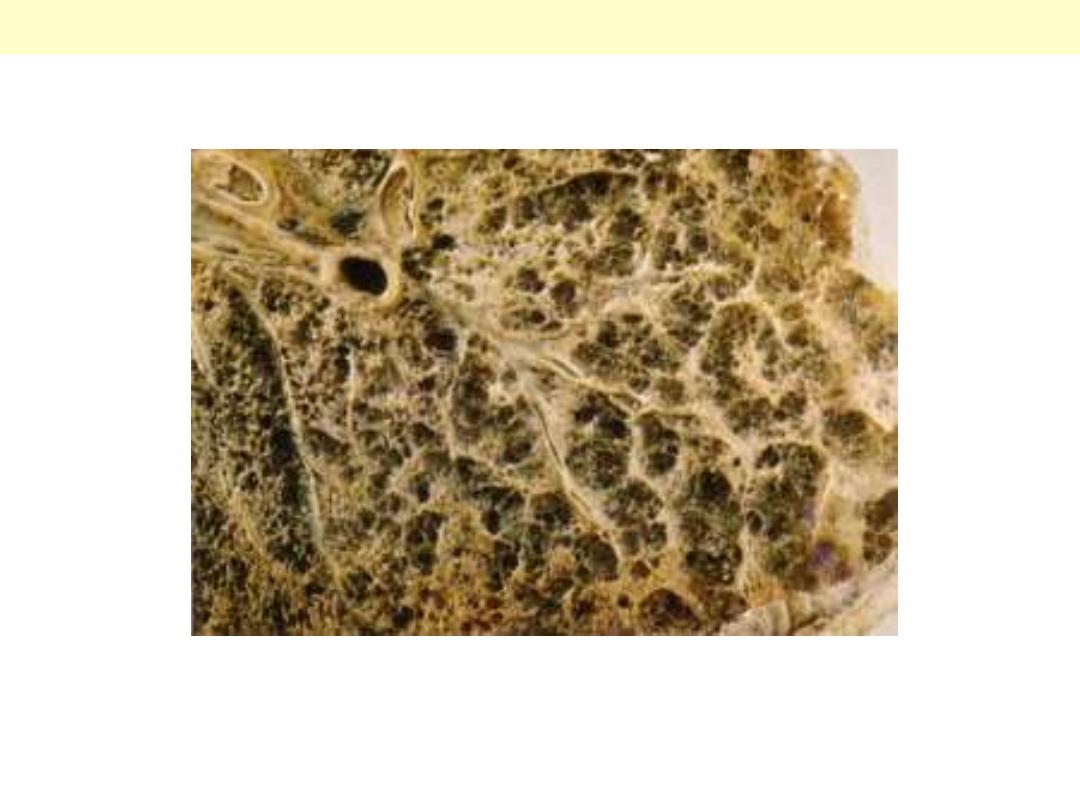

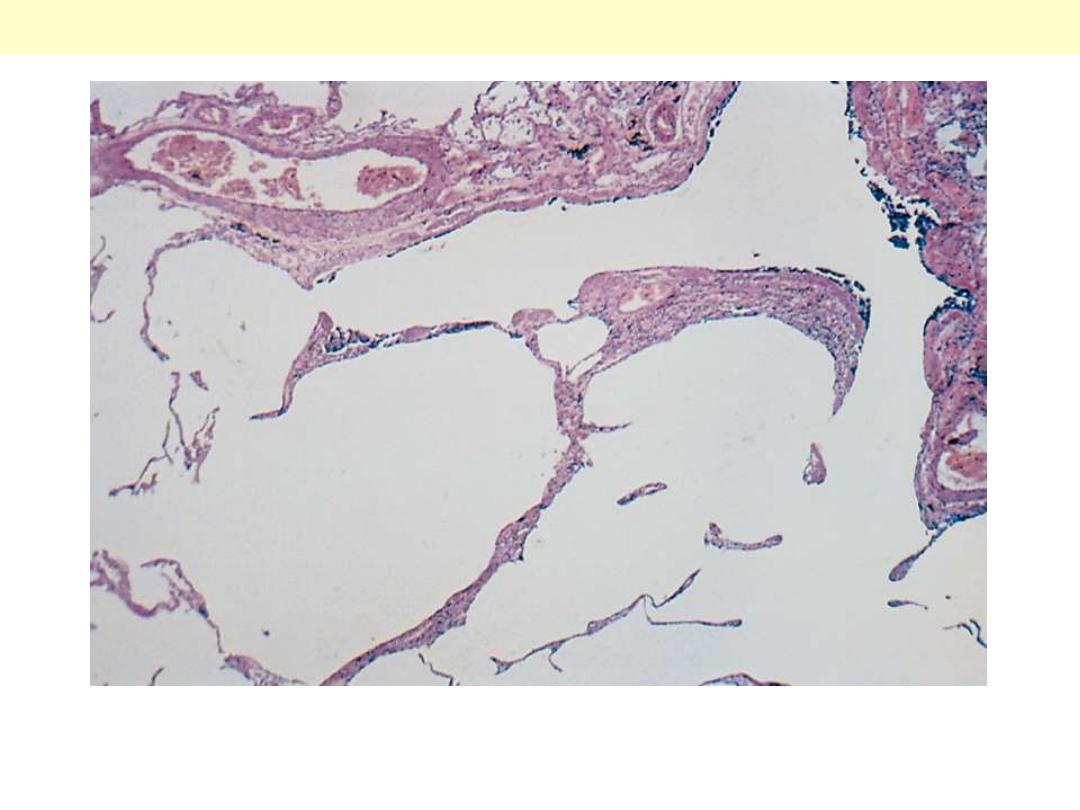

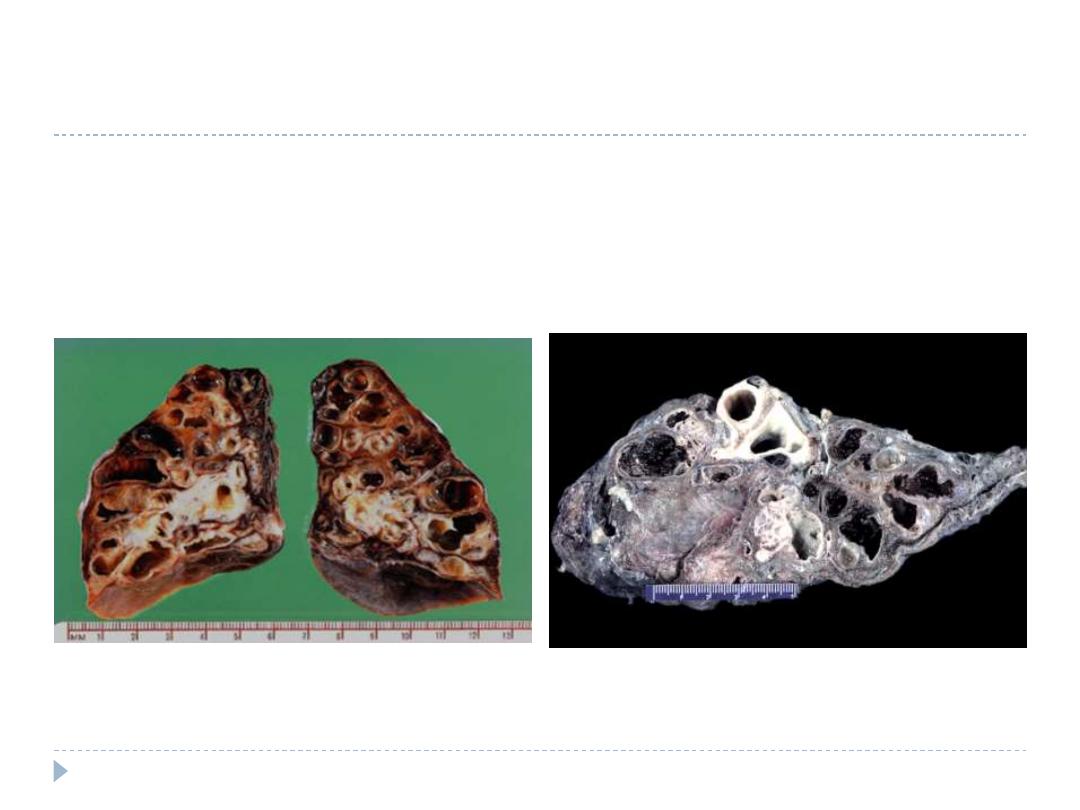

Panacinar emphysema

The 'substance' of the lung has been almost

completely lost. When such lungs are

removed from the body they are soft and

can often be squeezed into a small ball. The

pathology can be demonstrated by inflating

the intact lung by running formalin into the

main bronchus, allowing it to float in

formalin for 48 hours for fixation, then

slicing it with a long, sharp knife. As the

lung is cut, the formalin runs out of the

emphysematous spaces but the holey organ

can be examined by immersing the slices in

water, as was done for this photograph.

Pan-acinar destructive emphysema – severe emphysema.

The chest cavity is opened at autopsy to reveal

numerous large bullae apparent on the surface of the

lungs in a patient dying with emphysema. Bullae are

large dilated airspaces that bulge out from beneath

the pleura. Emphysema is characterized by a loss of

lung parenchyma by destruction of alveoli so that

there is permanent dilation of airspaces.

Advanced emphysema

There is marked enlargement of airspaces, with thinning and

destruction of alveolar septa.

Pulmonary emphysema

Course & prognosis

With the loss of elastic tissue in the surrounding alveolar septa, there is

reduced radial traction on the small airways.

As a result, they tend to collapse during expiration-an important cause

of chronic airflow obstruction in severe emphysema.

The patient is

barrel-chested and dyspneic

, with obviously prolonged

expiration.

Hyperventilation is prominent thus gas exchange is adequate and blood

gas values are relatively normal i.e. there is no cyanosis.

Patients with emphysema and chronic bronchitis usually have less

prominent dyspnea and respiratory drive, so they retain carbon

dioxide, become hypoxic, and are often cyanotic.

The eventual outcome of emphysema is the gradual development of

secondary pulmonary hypertension,

arising from both hypoxia-induced

pulmonary vascular spasm and loss of pulmonary capillary surface

area from alveolar destruction and stretching.

Death from emphysema is related to either pulmonary failure, or right-

sided heart failure (cor pulmonale).

Conditions Related to Emphysem

a

Several conditions resemble but are not really emphysema, these include

a.

Compensatory emphysema

refers to dilation of alveoli in

response to

loss of lung substance

elsewhere, as in residual

lung tissue after surgical removal of a diseased lung or lobe.

b. Obstructive overinflation:

the lung expands because air is

trapped within it. A common cause is

subtotal obstruction

by a

tumor or foreign object, & mucous plugs in asthmatic patients. It

can be a life-threatening emergency if the affected portion extends

sufficiently to compress the remaining normal lung.

c. Bullous emphysema

refers to any form of emphysema that

produces

bullae (spaces >1 cm in diameter).

They represent

localized accentuations of one of the four forms of emphysema

, are

most often subpleural that with rupture leads to pneumothorax.

d. Mediastinal (interstitial) emphysema

signifies the entrance of air into the

connective tissue of the

lung, mediastinum, and subcutaneous tissue.

It may spontaneous as with a sudden increase in intra-

alveolar pressure (associated with vomiting or violent

coughing) that causes a tear, with dissection of air into the

connective tissue.

It is also likely to occur in

patients on respirators who have

partial bronchiolar obstruction or in persons who suffer a

perforating injury (e.g., a fractured rib).

When the interstitial air enters the subcutaneous tissue, the

patient may blow up like a balloon, with marked swelling of

the head and neck.

CHRONIC BRONCHITIS

is common among cigarette smokers

and in smog-ridden cities. The diagnosis of chronic bronchitis is clinical; it

is defined as

"a persistent productive cough for at least 3 consecutive months

in at least 2 consecutive years."

Pathogenesis

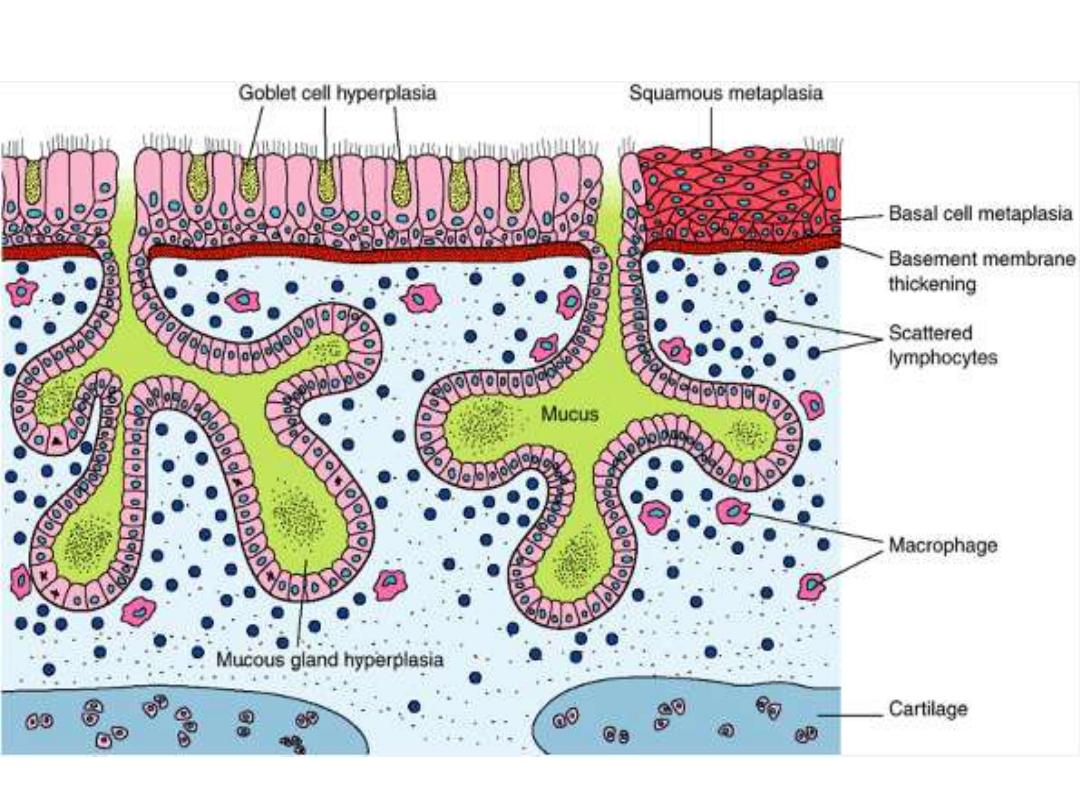

The distinctive feature of this disease is

hypersecretion of mucus

,

beginning in the

large airways

.

Although the single most important cause is

cigarette smoking

, other air

pollutants, such as

sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dio

xide, may contribute.

These environmental irritants induce

hypertrophy of mucous glands

in

the trachea and main bronchi and a

marked increase in mucin-secreting

goblet cells in the surface epithelium of smaller bronchi and bronchiole

s.

In addition, these irritants cause inflammation with infiltration of

CD8+

T

cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.

Microbial infection is often present but has a

secondary role,

chiefly by

maintaining the inflammation.

Airflow obstruction in chronic bronchitis results from :

1. Small airway disease,

(chronic bronchiolitis) induced by goblet cell

metaplasia with mucus plugging of the bronchiolar lumen, inflammation,

and bronchiolar wall fibrosis

2. Coexistent emphysema:

while small airway disease is important in the

early and mild airflow obstruction, chronic bronchitis with significant

airflow obstruction is almost always complicated by emphysema.

Gross features

The mucosal lining of the larger airways is usually hyperemic and

edematous. It is often covered by a layer of mucus or mucopurulent

secretions.

The smaller bronchi and bronchioles may also be filled with similar

secretions.

The lumen of the bronchus is above. Note the marked thickening of the mucous gland layer

(approximately twice normal) and squamous metaplasia of lung epithelium.

Chronic bronchitis

ASTHMA

is "a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that causes recurrent

attacks of breathlessness".

The inflammation seems to cause an increase in airway responsiveness

(bronchospasm) to a variety of stimuli, which would cause no such ill

effects in nonasthmatic individuals.

In two-thirds

of the cases, the disease is

"extrinsic" (atopic)

due to IgE and

T

H

2-mediated immune responses to environmental antigens.

In the remaining

one-third

, asthma is

"intrinsic" (non-atopic)

and is

triggered by

non-immune stimuli such as aspirin; pulmonary infections,

especially viral (common cold); psychological stress,

etc.

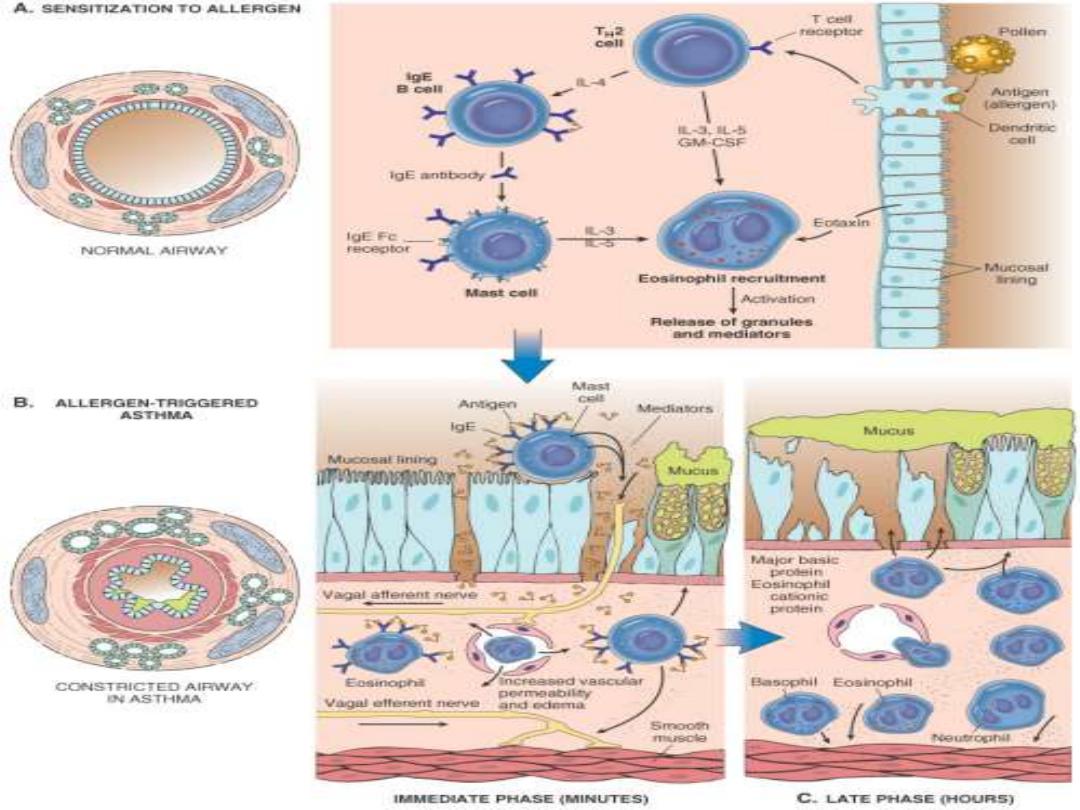

Pathogenesis

The major etiologic factors of asthma are

1. Genetic predisposition to type I hypersensitivity ("atopy"),

2. Airway inflammation

3. Bronchial hyper-responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.

The role of T

H

2:

the "atopic" form of asthma is associated with an excessive

T

H

2 reaction against environmental antigens. Three cytokines produced by T

H

2

cells are, in particular, responsible for most of the features of asthma;

1. IL-4 stimulates IgE production

2. IL-5 activates eosinophils

3. IL-13 stimulates mucus production

In addition, epithelial cells are activated to produce chemokines that recruit

more T

H

2 cells, eosinophils, & other leukocytes, thus amplifying the

inflammatory reaction.

The role of genetics:

in asthma the bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy and

the deposition of subepithelial collagen may be the result of a genetically

inherited predisposition.

ADAM33

is one of the genes implicated.

The role of mast cells:

these are part of the inflammatory infiltrate & contribute by secreting

growth factors that

stimulate smooth muscle proliferation.

Atopic asthma,

which usually begins in childhood, is triggered by

environmental antigens (dusts, pollen, animal dander, and foods).

In the airways the inhaled antigens

stimulates induction of T

H

2-type

cells and release of interleukins IL-4 and IL-5

.

This leads to synthesis of

IgE

that binds to mucosal mast cells.

Subsequent exposure of IgE-coated mast cells to the same antigen

causes the release of chemical mediators.

In addition, direct stimulation of subepithelial vagal receptors provokes

reflex bronchocospasm.

These occur within minutes after stimulation thus called

acute, or

immediate, response.

Mast cells release other cytokines that cause the influx of other

leukocytes, including eosinophils. These inflammatory cells

set the stage

for the late-phase reaction, which starts

4 to 8 hours later.

The role of eosinophils

: these cells are particularly important in the late phase.

Their effects are mediated by

1. Major basic protein and eosinophil cationic protein, which directly damage

airway epithelial cells.

2. Eosinophil peroxidase causes tissue damage through oxidative stress.

3. Leukotriene C

4

, which contribute to bronchospasm.

Viral infections of the respiratory tract and inhaled air pollutants such as

sulfur dioxide increase airway hyper-reactivity in both normal & non-atopic

asthmatics. In the latter, however, the bronchial spasm is much more severe

and sustained. It is thought that virus-induced inflammation of the

respiratory mucosa renders the subepithelial vagal receptors more sensitive to

irritants.

The ultimate humoral and cellular mediators of airway obstruction are common

to both atopic and non-atopic variants of asthma, and hence they are treated in a

similar way.

Drug-Induced Asthma:

several drugs provoke asthma, aspirin being the

most striking example. Presumably,

aspirin inhibits the cyclooxygenase

pathway of arachidonic acid metabolism without affecting the lipoxygenase

route, thereby shifting the balance toward bronchoconstrictor leukotrienes.

Occupational Asthma:

this form is stimulated by fumes (epoxy resins,

plastics), organic and chemical dusts (wood, cotton, platinum), gases

(toluene), and other chemicals. Asthma attacks usually develop after repeated

exposure to the inciting antigen(s).

Pathologic features

Gross features:

in fatal cases, the lungs are overdistended because of

overinflation.

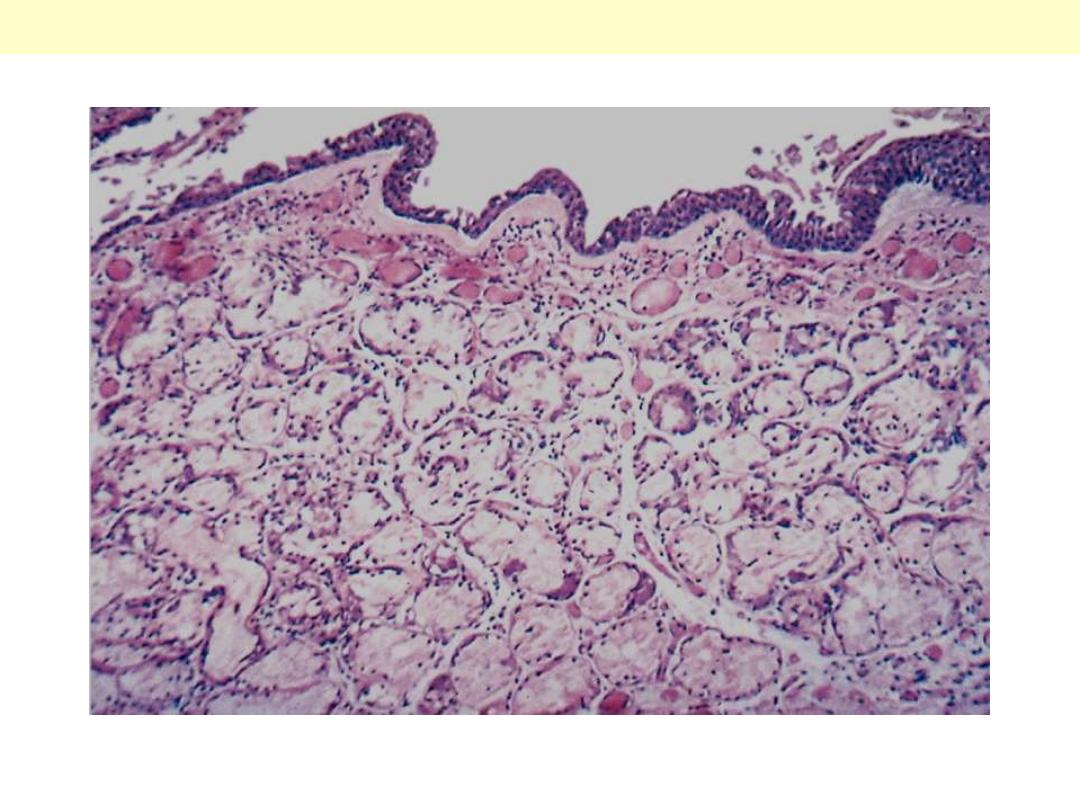

Microscopic features:

There is occlusion of bronchi and bronchioles by thick, tenacious mucous

plugs, which contain numerous eosinophils.

Structural changes of airways include

Thickening of the basement membrane of the bronchial epithelium

Edema and an inflammatory infiltrate in the bronchial walls, with a

prominence of eosinophils and mast cells.

An increase in the size of the submucosal glands.

Hypertrophy of the bronchial muscle cells.

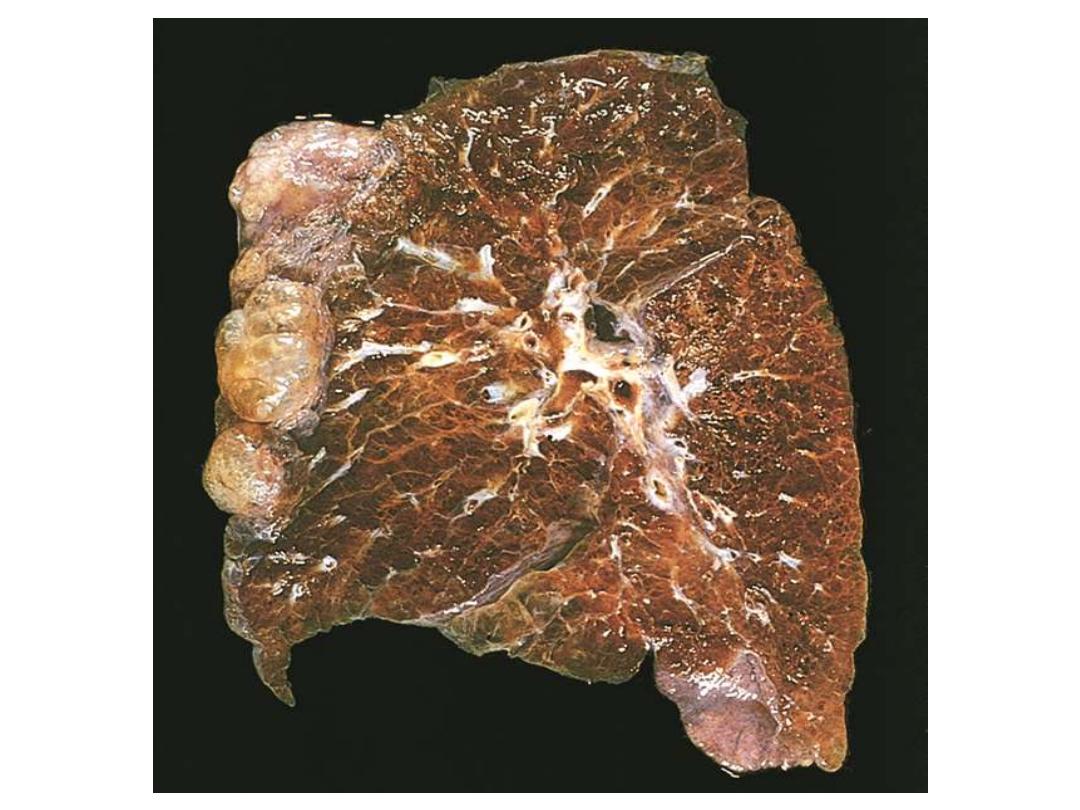

Bronchial asthma

This specimen shows a cross section of a lung from an asthmatic

with obstruction of major airways (bronchi). The lung is collapsed,

due to absorption of air trapped by obstruction of airways (bronchi

and bronchioles). The large and medium-sized bronchioles are

thick-walled and they are filled with greyish-white, jelly-like mucus

plugs. It is these plugs, rather than spasm of airway muscle, that

have caused the partial collapse of the lung, low arterial oxygen and

high carbon dioxide.

Bronchial asthma

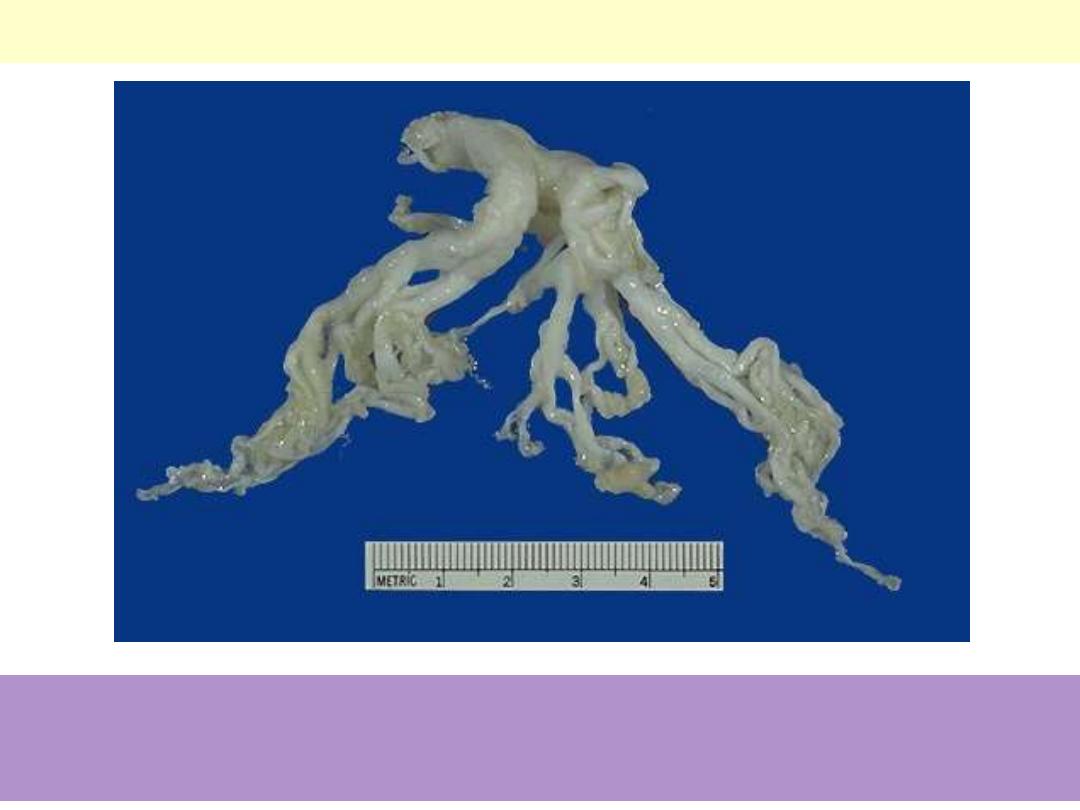

This cast of the bronchial tree is formed of inspissated mucus and was coughed up by a patient during

an asthmatic attack. The outpouring of mucus from hypertrophied bronchial submucosal glands, the

bronchoconstriction, and dehydration all contribute to the formation of mucus plugs that can block

airways in asthmatic patients.

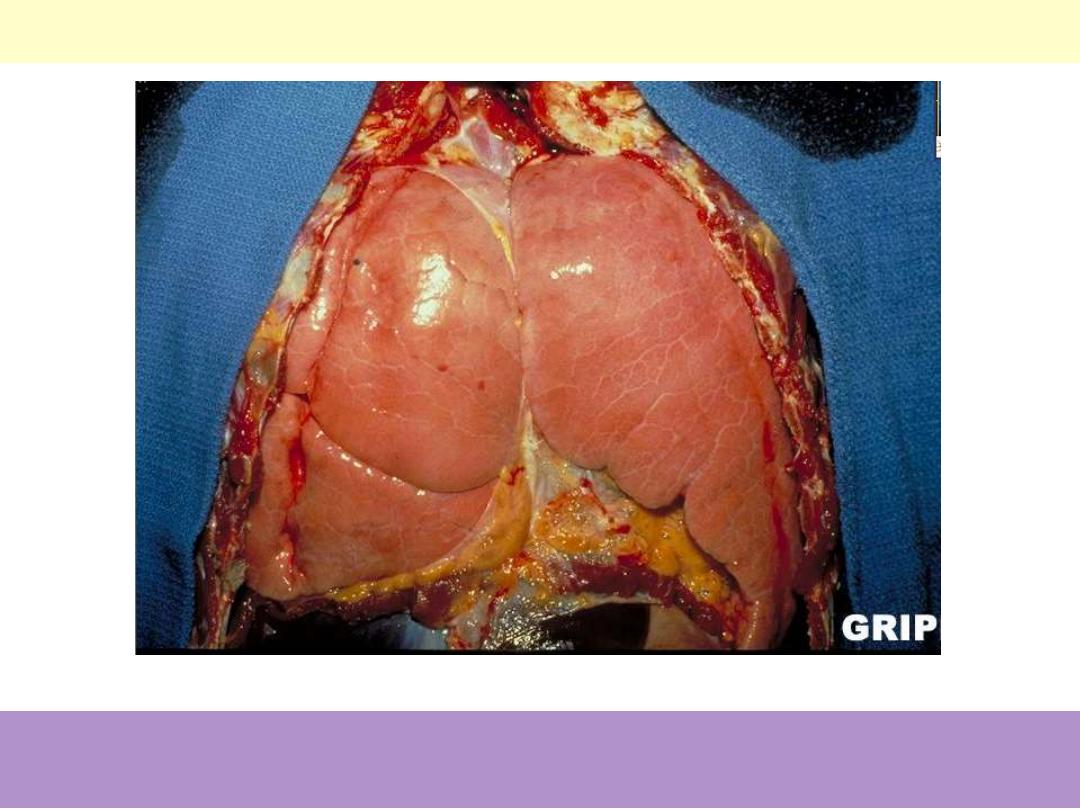

Bronchial asthma: overinflation of the lungs

Status asthmaticus: Note the overinflated lungs secondary to airway

obstruction.

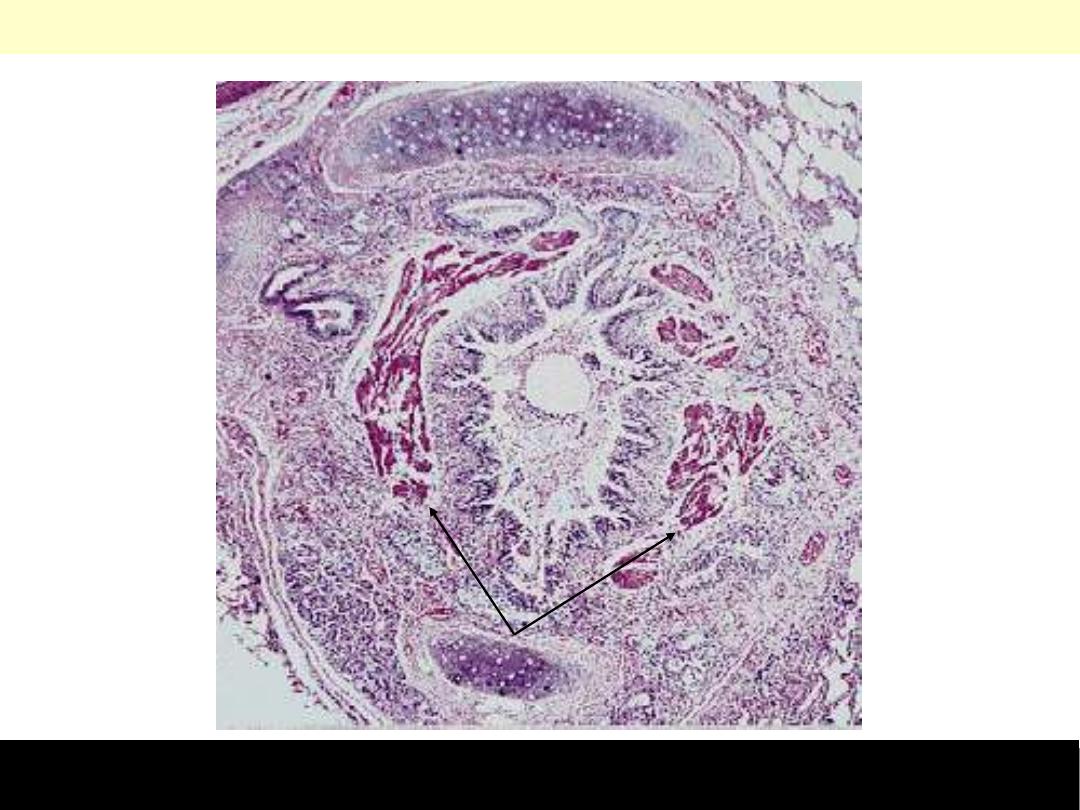

Bronchial asthma

Asthma is characterized by reversible airways obstruction in small airways. The latter is due to a

combination of bronchospasm and mucus plugging. Note mucus plugging of the lumen, smooth muscle

cell prominence (arrow), and the intense inflammatory cell infiltration.

Course & prognosis

An attack of asthma is characterized by severe dyspnea with wheezing;

the chief difficulty lies in expiration.

The victim struggles to get air into the lungs and then cannot get it out,

so that there is progressive hyperinflation of the lungs with air trapped

distal to the bronchi, which are constricted and filled with mucus and

debris.

In the usual case, attacks last from 1 to several hours and subside either

spontaneously or with therapy.

Occasionally a severe paroxysm occurs that does not respond to

therapy and persists for days and even weeks

(status asthmaticus)

.

The associated hypercapnia, acidosis, and severe hypoxia may be fatal.

BRONCHIECTASIS

refers to

"the permanent dilation of bronchi and bronchioles

caused by destruction of the musclulo- elastic supporting tissues,

resulting from or associated with chronic necrotizing infections."

The disease is secondary to persisting infection or obstruction

caused by a variety of conditions.

Once developed, it gives rise to symptoms dominated by

cough

and expectoration of copious amounts of purulent, foul

sputum.

Diagnosis depends on an appropriate history along with

radiographic demonstration of bronchial dilation.

The conditions that most commonly predispose to

bronchiectasis include the following:

1.

Bronchial obstruction

e.g. by tumors, foreign bodies. Under these conditions, the

bronchiectasis is localized to the obstructed segment.

Bronchiectasis can also complicate

atopic asthma and

chronic bronchitis through mucus impaction.

In

cystic fibrosis,

widespread severe bronchiectasis results

from obstruction and infection caused by the secretion of

abnormally viscid mucus.

Kartagener syndrome

, an autosomal recessive disorder, is

frequently associated with bronchiectasis and sterility in

males.

Structural abnormalities of the cilia

impair

mucociliary clearance in the airways, leading to persistent

infections, and reduce the mobility of spermatozoa.

2. Necrotizing, or suppurative, pneumonia

,

particularly with virulent organisms such as

Staphylococcus aureus or Klebsiella spp

., may predispose

to bronchiectasis.

In the past, postinfective bronchiectasis was sometimes a

sequel to the childhood pneumonias that complicated

measles, whooping cough, and influenza

, but this has

substantially decreased with the advent of successful

immunization.

Post-tubercculosis bronchiectasis continues to be a

significant cause in endemic areas.

Pathogenesis

Two processes are crucial and tangled in the pathogenesis of

bronchiectasis:

obstruction and chronic persistent infection.

Either of

these two processes may come first.

Normal clearance mechanisms are impaired by obstruction, so

secondary infection soon follows; conversely, chronic infection in time

causes damage to bronchial walls, leading to weakening and dilation.

For example,

obstruction caused by a bronchogenic carcinoma

or a

foreign body impairs clearance of secretions, providing a fertile soil for

superimposed infection.

The resultant inflammatory damage to the bronchial wall and the

accumulating exudate further distend the airways, leading to

irreversible dilation.

A persistent necrotizing inflammation in the bronchi or bronchioles

may cause obstructive secretions, inflammation throughout the wall

(with peribronchial fibrosis and traction on the walls), and eventually

dilation.

Gross features

Usually there is bilateral involvement of the lower lobes

When tumors or aspiration of foreign bodies lead to bronchiectasis, involvement

may be sharply localized to a single segment of the lungs.

The airways may be dilated up to 4 times their usual diameter and can be

followed almost to the pleural surfaces

Microscopic features

There is intense acute and chronic inflammatory exudate within the walls of the

bronchi and bronchioles.

The desquamation of lining epithelium causes extensive areas of ulceration.

When healing occurs, the lining epithelium may regenerate completely.

In chronic cases there is fibrosis of the bronchial and bronchiolar walls and

peribronchiolar areas.

In some instances, the necrotizing inflammation destroys the bronchial or

bronchiolar walls and forms a

lung abscess.

In cases of severe, widespread bronchiectasis

hypoxemia, hypercapnia,

pulmonary hypertension, and (rarely) cor pulmonale occur.

Metastatic brain abscesses and reactive amyloidosis are other, less frequent

complications.

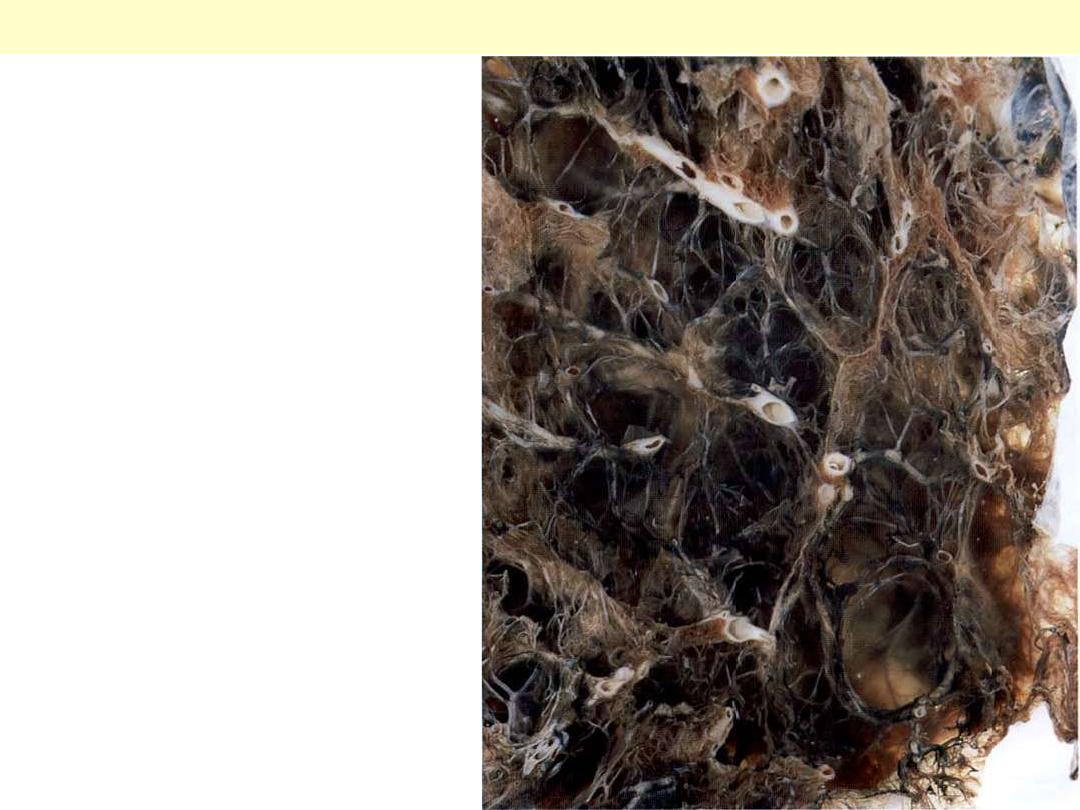

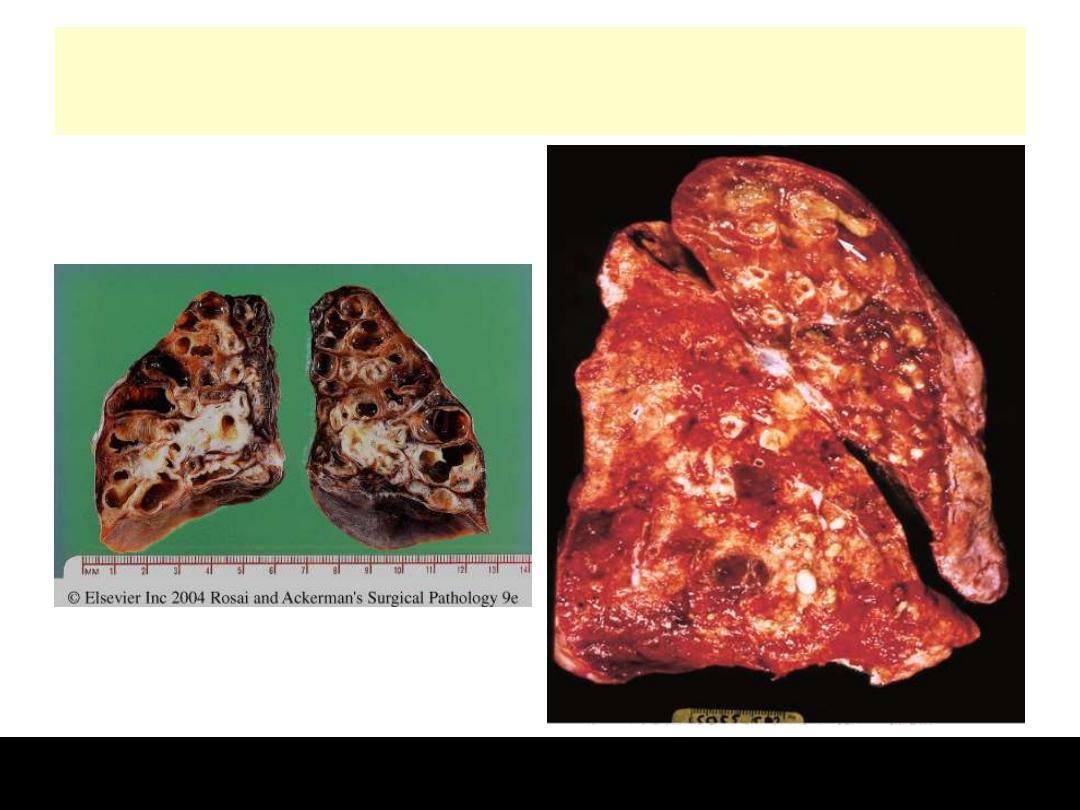

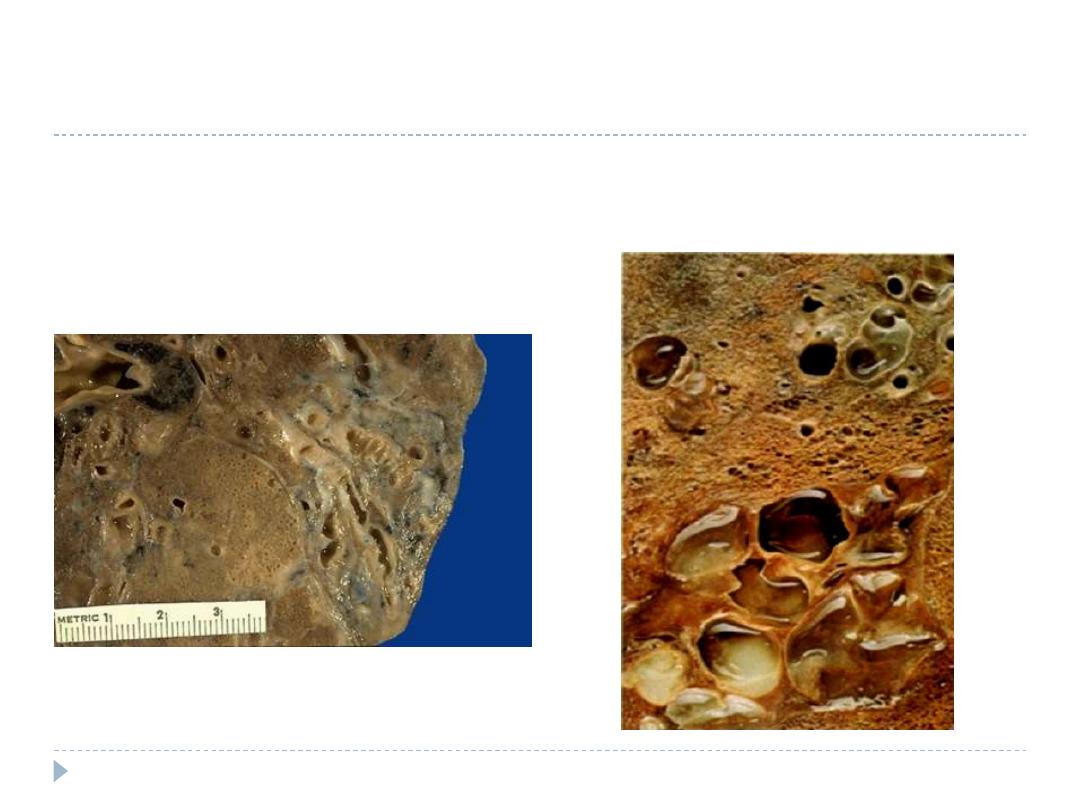

Bronchiectasis

Extensive bilateral bronchiectasis; the massively dilated bronchi extend almost to the pleura. Widespread

bronchiectasis is typical for patients with cystic fibrosis who have recurrent infections and obstruction of

airways by mucus throughout the lungs.

Extensive bilateral bronchiectasis; the massively

dilated bronchi extend almost to the pleura.

Widespread bronchiectasis is typical for patients

with cystic fibrosis who have recurrent infections

and obstruction of airways by mucus throughout the

lungs.

Cross-section of lung demonstrating

dilated bronchi extending almost to the

pleura.

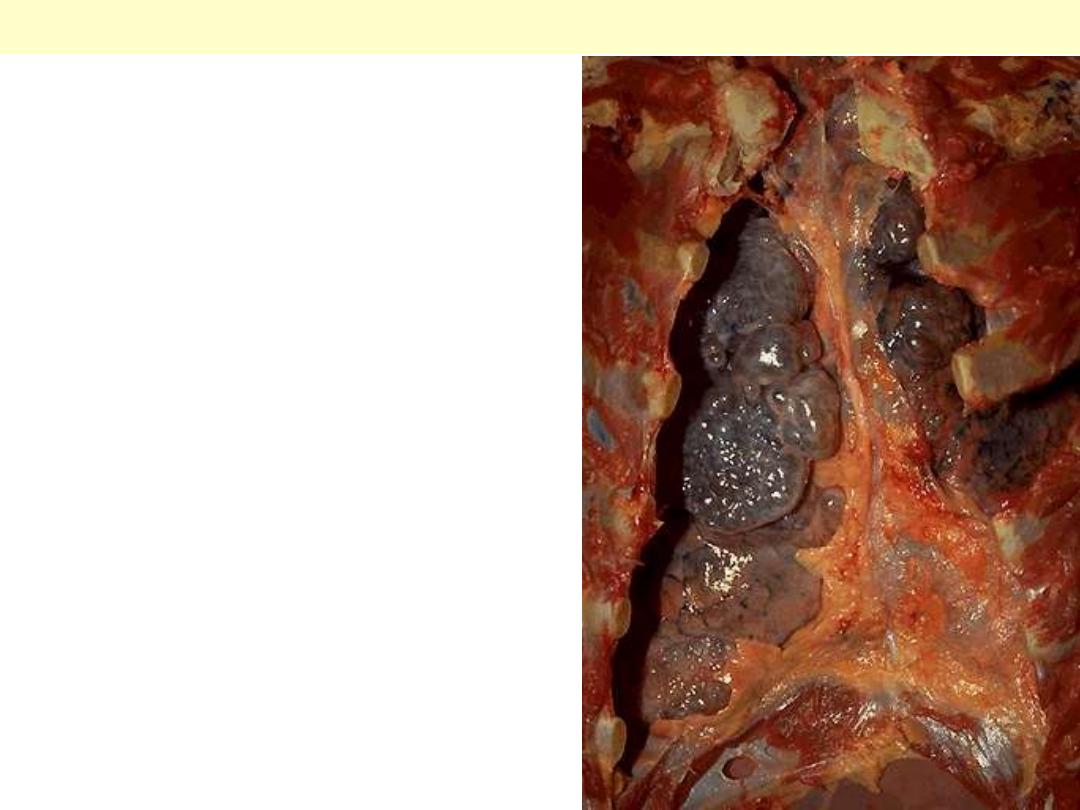

A closer view demonstrates the focal area of dilated bronchi with

bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis tends to be localized with disease

processes such as neoplasms and aspirated foreign bodies that block a

portion of the airways. Note that the dilated bronchi can be traced down

to the pleura.

Segmental distribution of bronchiectasis. The bronchi

are dilated into cavities. The dilated bronchi are filled

with gelatinous inspissated mucus.

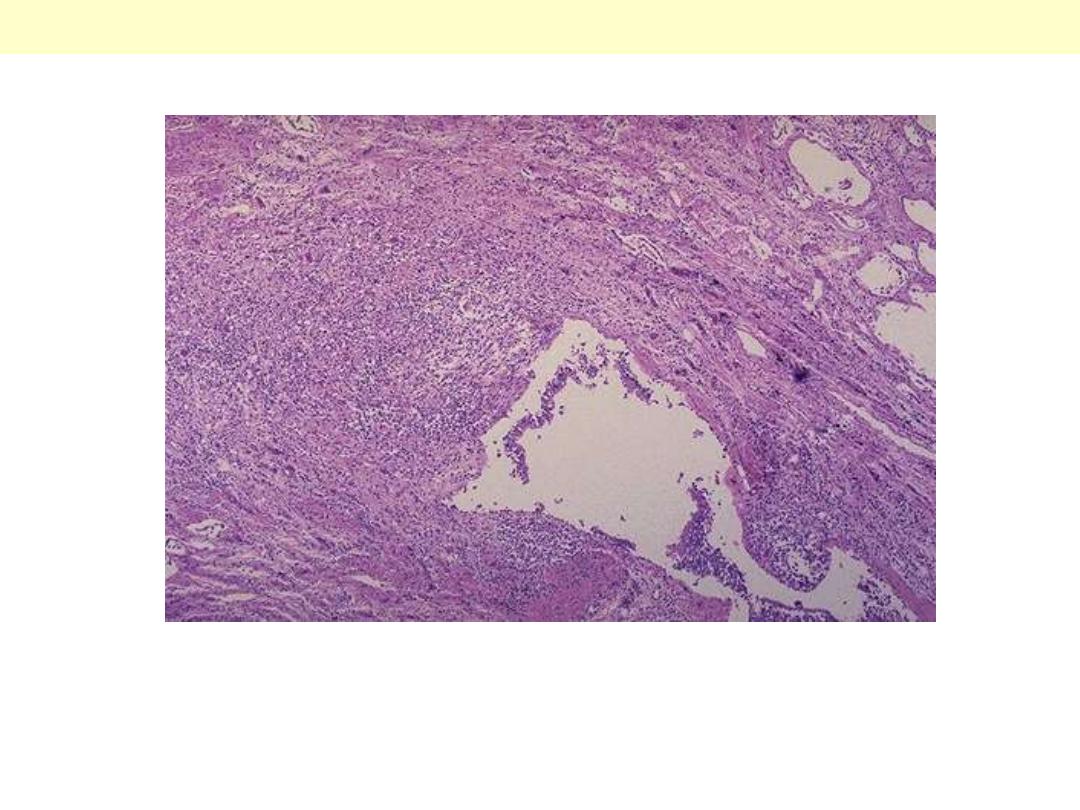

The mid lower portion of this photomicrograph demonstrates a dilated bronchus in which the mucosa

and wall is not clearly seen because of the necrotizing inflammation with destruction.

Bronchiectasis