Lecture 4

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

1

Volume and Osmolality of Extracellular and Intracellular Fluids in Abnormal States

Some of the different factors that can cause extracellular and intracellular volumes to change

markedly are ingestion of water, dehydration, intravenous infusion of different types of

solutions, loss of large amounts of fluid from the gastrointestinal tract, and loss of abnormal

amounts of fluid by sweating or through the kidneys. One can calculate both the changes in

intracellular and extracellular fluid volumes and the types of therapy that should be instituted if

the following basic principles are kept in mind:

1. Water moves rapidly across cell membranes; therefore, the osmolarities of intracellular and

extracellular fluids remain almost exactly equal to each other except for a few minutes after a

change in one of the compartments.

2. Cell membranes are almost completely impermeable to many solutes; therefore, the number of

osmoles in the extracellular or intracellular fluid generally remains constant unless solutes are

added to or lost from the extracellular compartment. With these basic principles in mind, we can

analyze the effects of different abnormal fluid conditions on extracellular and intracellular fluid

volumes and osmolarities.

Fluids used in clinical practice:

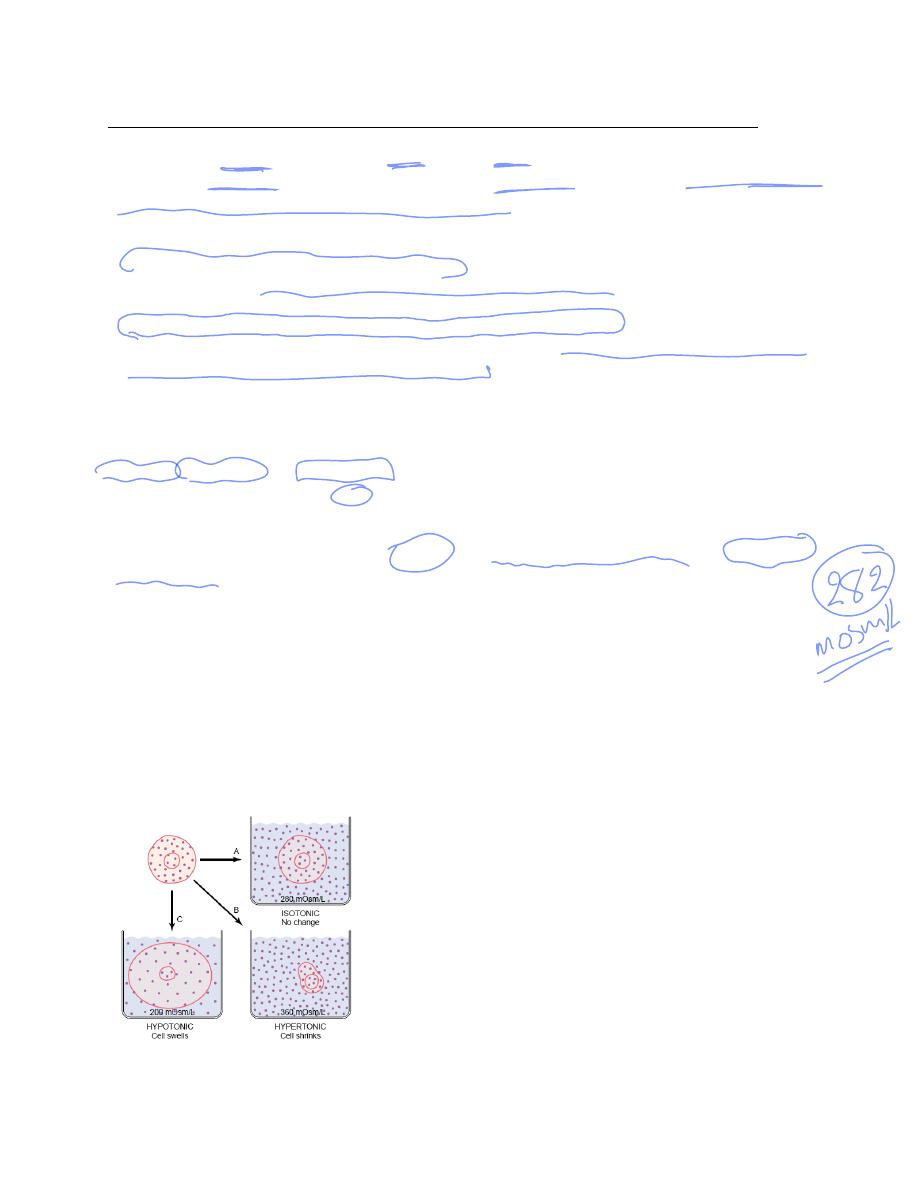

Isotonic, Hypotonic, and Hypertonic Fluids. If a cell is placed in a solution of impermeant

solutes having an osmolarity of 282 mOsm/L, the cells will not shrink or swell because the water

concentration in the intracellular and extracellular fluids is equal and the solutes cannot enter or

leave the cell. Such a solution is said to be isotonic because it neither shrinks nor swells the cells.

Examples of isotonic solutions include a 0.9 per cent solution of sodium chloride or a 5 per cent

glucose solution. These solutions are important in clinical medicine because they can be infused

into the blood without the danger of upsetting osmotic equilibrium between the intracellular and

extracellular fluids. If a cell is placed into a hypotonic solution that has a lower concentration of

impermeant solutes (less than 282 mOsm/L), water will diffuse into the cell, causing it to swell;

water will continue to diffuse into the cell, diluting the intracellular fluid while also

concentrating the extracellular fluid until both solutions have about the same osmolarity.

Solutions of sodium chloride with a concentration of less than 0.9 per cent are hypotonic and

cause cells to swell. If a cell is placed in a hypertonic solution having a higher concentration of

impermeant solutes, water will flow out of the cell into the extracellular fluid, concentrating the

intracellular fluid and diluting the extracellular fluid. In this case, the cell will shrink until the

two concentrations become equal. Sodium chloride solutions of greater than 0.9 per cent are

hypertonic.

Lecture 4

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

2

Isosmotic, Hyperosmotic, and Hypo-osmotic Fluids. The terms isotonic, hypotonic, and

hypertonic refer to whether solutions will cause a change in cell volume. The tonicity of

solutions depends on the concentration of impermeant solutes. Some solutes, however, can

permeate the cell membrane. Solutions with an osmolarity the same as the cell are called

isosmotic, regardless of whether the solute can penetrate the cell membrane. The terms

hyperosmotic and hypo-osmotic refer to solutions that have a higher or lower osmolarity,

respectively, compared with the normal extracellular fluid, without regard for whether the solute

permeates the cell membrane. Highly permeating substances, such as urea, can cause transient

shifts in fluid volume between the intracellular and extracellular fluids, but given enough time,

the concentrations of these substances eventually become equal in the two compartments and

have little effect on intracellular volume under steady-state conditions.

Effect of Adding Saline Solution to the Extracellular Fluid

If an isotonic saline solution is added to the extracellular fluid compartment, the osmolarity of

the extracellular fluid does not change; therefore, no osmosis occurs through the cell membranes.

The only effect is an increase in extracellular fluid volume .The sodium and chloride largely

remain in the extracellular fluid because the cell membrane behaves as though it were virtually

impermeable to the sodium chloride.

If a hypertonic solution is added to the extracellular fluid, the extracellular osmolarity

increases and causes osmosis of water out of the cells into the extracellular compartment. Again,

almost all the added sodium chloride remains in the extracellular compartment, and fluid diffuses

from the cells into the extracellular space to achieve osmotic equilibrium. The net effect is an

increase in extracellular volume (greater than the volume of fluid added), a decrease in

intracellular volume, and a rise in osmolarity in both compartments.

If a hypotonic solution is added to the extracellular fluid, the osmolarity of the extracellular

fluid decreases and some of the extracellular water diffuses into the cells until the intracellular

and extracellular compartments have the same osmolarity. Both the intracellular and the

extracellular volumes are increased by the addition of hypotonic fluid, although the intracellular

volume increases to a greater extent.

Glucose and Other Solutions Administered for Nutritive Purposes

Many types of solutions are administered intravenously to provide nutrition to people who

cannot otherwise take adequate amounts of nutrition. Glucose solutions are widely used, and

amino acid and homogenized fat solutions are used to a lesser extent. When these solutions are

administered, their concentrations of osmotically active substances are usually adjusted nearly to

isotonicity, or they are given slowly enough that they do not upset the osmotic equilibrium of the

body fluids. After the glucose or other nutrients are metabolized, an excess of water often

remains, especially if additional fluid is ingested. Ordinarily, the kidneys excrete this in the form

of a very diluted urine. The net result, therefore, is the addition of only nutrients to the body.

Lecture 4

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

3

Fluid Filtration Across Capillaries

The capillary wall is a thin membrane made up of endothelial cells. Substances pass through the

junctions between endothelial cells and through fenestrations, when they are present. Some also

pass through the cells by vesicular transport or, in the case of lipid-soluble substances, through

the cytoplasm. The factors other than vesicular transport that are responsible for transport across

the capillary wall are diffusion and filtration. Diffusion is quantitatively much more important in

terms of the exchange of nutrients and waste materials between blood and tissue. O

2

and glucose

are in higher concentration in the blood stream than in the interstitial fluid and diffuse into the

interstitial fluid, whereas CO

2

diffuses in the opposite direction.

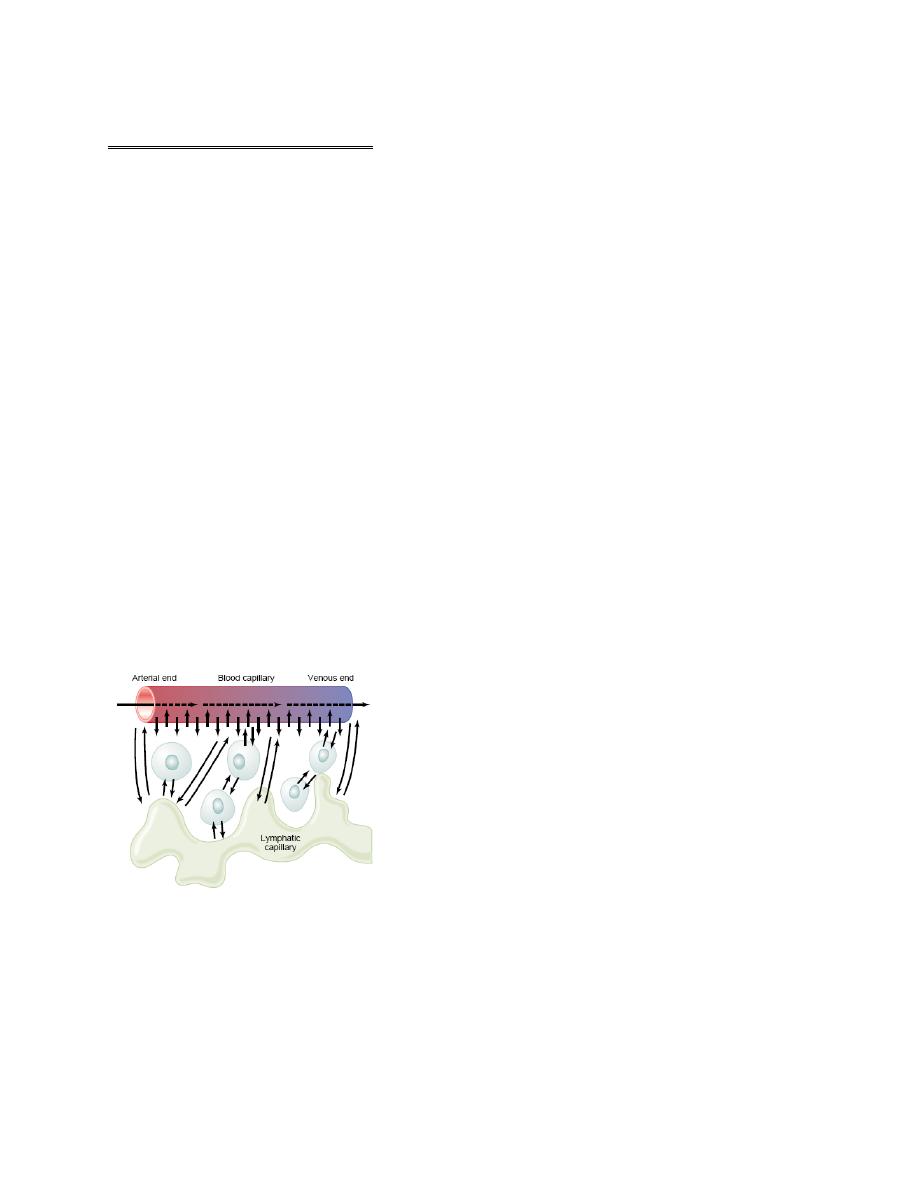

Fluid moves into the interstitial space at the arteriolar end of the capillary, where the filtration

pressure across its wall exceeds the oncotic pressure, and into the capillary at the venular end,

where the oncotic pressure exceeds the filtration pressure.

The hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries tends to force fluid and its dissolved substances

through the capillary pores into the interstitial spaces. Conversely, osmotic pressure caused by

the plasma proteins (called colloid osmotic pressure) tends to cause fluid movement by osmosis

from the interstitial spaces into the blood. This osmotic pressure exerted by the plasma proteins

normally prevents significant loss of fluid volume from the blood into the interstitial spaces. To

distinguish this osmotic pressure from that which occurs at the cell membrane, it is called either

colloid osmotic pressure or oncotic pressure. The term “colloid” osmotic pressure is derived

from the fact that a protein solution resembles a colloidal solution despite the fact that it is

actually a true molecular solution.

Also important is the lymphatic system, which returns to the circulation the small amounts of

excess protein and fluid that leak from the blood into the interstitial spaces.

Normal Values for Plasma Colloid Osmotic Pressure.

The colloid osmotic pressure of normal human plasma averages about 28 mm Hg; 19 mm of this

is caused by molecular effects of the dissolved protein and 9 mm by the Donnan effect—that is,

extra osmotic pressure caused by sodium, potassium, and the other cations held in the plasma by

the proteins

Interstitial Fluid Colloid Osmotic Pressure

Although the size of the usual capillary pore is smaller than the molecular sizes of the plasma

proteins, this is not true of all the pores. Therefore, small amounts of plasma proteins do leak

Lecture 4

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

4

through the pores into the interstitial spaces. The total quantity of protein in the entire 12 liters of

interstitial fluid of the body is slightly greater than the total quantity of protein in the plasma

itself, but because this volume is four times the volume of plasma, the average protein

concentration of the interstitial fluid is usually only 40 per cent of that in plasma, or about 3

g/dl. Quantitatively, the average interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure for this concentration

of proteins is about 8 mm Hg.

Exchange of Fluid Volume Through the Capillary Membrane

The average capillary pressure at the arterial ends of the capillaries is 15 to 25 mm Hg greater

than at the venous ends. Because of this difference, fluid “filters” out of the capillaries at their

arterial ends, but at their venous ends fluid is reabsorbed back into the capillaries. Thus, a

small amount of fluid actually “flows” through the tissues from the arterial ends of the capillaries

to the venous ends. The dynamics of this flow are as follows.

Analysis of the Forces Causing Filtration at the Arterial End of the Capillary.

The approximate average forces operative at the arterial end of the capillary that cause

movement through the capillary membrane are shown as follows:

Forces tending to move fluid outward:

Capillary pressure (arterial end of capillary) 30

Negative interstitial free fluid pressure 3

Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure 8

total outward force 41

Forces tending to move fluid inward:

Plasma colloid osmotic pressure 28

total inward force 28

Summation of forces:

Outward 41

Inward 28

net outward force (at arterial end) 13

Thus, the summation of forces at the arterial end of the capillary shows a net filtration pressure

of 13 mm Hg, tending to move fluid outward through the capillary pores. This 13 mm Hg

filtration pressure causes, on the average, about 1/200 of the plasma in the flowing blood to filter

out of the arterial ends of the capillaries into the interstitial spaces each time the blood passes

through the capillaries.

Analysis of Reabsorption at the Venous End of the Capillary.

The low blood pressure at the venous end of the capillary changes the balance of forces in favor

of absorption as follows:

Forces tending to move fluid inward:

Plasma colloid osmotic pressure 28

total inward force 28

Forces tending to move fluid outward:

Capillary pressure (venous end of capillary) 10

Negative interstitial free fluid pressure 3

Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure 8

total outward force 21

Lecture 4

Physiology

Dr. Affan Ezzat

5

Summation of forces:

Inward 28

Outward 21

net inward force 7

Thus, the force that causes fluid to move into the capillary, 28 mm Hg, is greater than that

opposing reabsorption, 21 mm Hg. The difference, 7 mm Hg, is the net reabsorption pressure at

the venous ends of the capillaries. This reabsorption pressure is considerably less than the

filtration pressure at the capillary arterial ends, but remember that the venous capillaries are more

numerous and more permeable than the arterial capillaries, so that less reabsorption pressure is

required to cause inward movement of fluid. The reabsorption pressure causes about nine tenths

of the fluid that has filtered out of the arterial ends of the capillaries to be reabsorbed at the

venous ends. The remaining one tenth flows into the lymph vessels and returns to the circulating

blood.

Edema: Excess Fluid in the Tissues

Edema refers to the presence of excess fluid in the body tissues. In most instances, edema occurs

mainly in the extracellular fluid compartment, but it can involve intracellular fluid as well.

Intracellular Edema

Two conditions are especially prone to cause intracellular swelling: (1) depression of the

metabolic systems of the tissues, and (2) lack of adequate nutrition to the cells.

For example, when blood flow to a tissue is decreased, the delivery of oxygen and nutrients is

reduced. If the blood flow becomes too low to maintain normal tissue metabolism, the cell

membrane ionic pumps become depressed. When this occurs, sodium ions that normally leak

into the interior of the cell can no longer be pumped out of the cells, and the excess sodium ions

inside the cells cause osmosis of water into the cells.

Extracellular Edema

Extracellular fluid edema occurs when there is excess fluid accumulation in the extracellular

spaces.