Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

1

Objectives:

By the end of these two lectures the student will be able to:

Describe the basic components of the cell membrane.

Explain the transport process through cell membranes.

Define diffusion and its types.

List the factors that affect the net rate of diffusion.

Define osmosis.

Explain the active transport of substances through membranes.

Give examples on the types of active transport.

Cell Physiology:

The basic living unit of the body is the cell. Each organ is an aggregate of many different cells held

together by intercellular supporting structures. Each type of cell is specially adapted to perform one or a few

particular functions. For instance, the red blood cells, numbering 25 trillion in each human being, transport

oxygen from the lungs to the tissues. The entire body contains about 100 trillion cells.

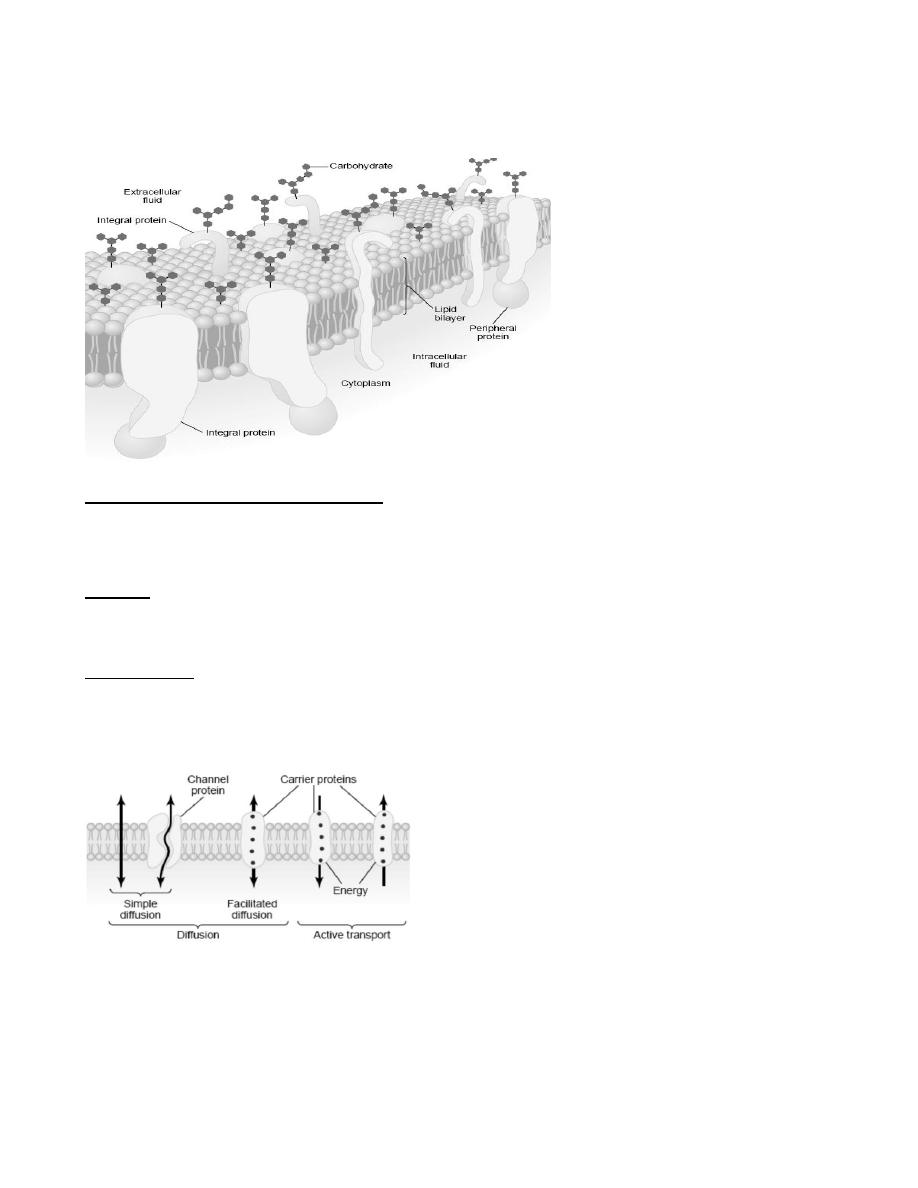

Membranous Structures of the Cell

Most organelles of the cell are covered by membranes composed primarily of lipids and proteins. These

membranes include the cell membrane, nuclear membrane, membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum, and

membranes of the mitochondria, lysosomes, and Golgi apparatus. The lipids of the membranes provide a barrier

that impedes the movement of water and water-soluble substances from one cell compartment to another because

water is not soluble in lipids. However, protein molecules in the membrane often do penetrate all the way

through the membrane.

The Cell Membrane:

The cell membrane (also called the plasma membrane), which envelops the cell, is a thin, pliable, elastic

structure only 7.5 to 10 nanometers thick. It is composed almost entirely of proteins and lipids. The approximate

composition is proteins, 55%; phospholipids, 25%; cholesterol, 13%; other lipids, 4%; and carbohydrates, 3%.

Its basic structure is a lipid bilayer, which is a thin, double-layered film of lipids—each layer only one molecule

thick—that is continuous over the entire cell surface. Interspersed in this lipid film are large globular protein

molecules. The basic lipid bilayer is composed of phospholipid molecules. One end of each phospholipid

molecule is soluble in water; that is, it is hydrophilic. The other end is soluble only in fats; that is, it is

hydrophobic. The hydrophilic phosphate portions then constitute the two surfaces of the complete cell

membrane, in contact with intracellular water on the inside of the membrane and extracellular water on the

outside surface. The lipid layer in the middle of the membrane is impermeable to the usual water-soluble

substances, such as ions, glucose, and urea. Conversely, fat-soluble substances, such as oxygen, carbon dioxide,

and alcohol, can penetrate this portion of the membrane with ease.

Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

2

The Cell Membrane Proteins:

The membrane proteins are globular masses floating in the lipid bilayer, most of which are glycoproteins. Two

types of proteins occur: integral proteins that protrude all the way through the membrane and peripheral

proteins that are attached only to one surface of the membrane and do not penetrate all the way through.

The integral proteins act as (1)structural channels (or pores) through which water molecules and water-soluble

substances, especially ions, can diffuse between the extracellular and intracellular fluids. (2) carrier proteins for

transporting substances that otherwise could not penetrate the lipid bilayer (bind with molecules or ions that are

to be transported; conformational changes in the protein molecules then move the substances through the

interstices of the protein to the other side of the membrane). Both the channel proteins and the carrier proteins

are usually highly selective in the types of molecules or ions that are allowed to cross the membrane.

(3) enzymes (catalyze chemical reactions).

(4) receptors for water-soluble chemicals, such as peptide hormones, that do not easily penetrate the cell

membrane. Interaction of cell membrane receptors with specific ligands that bind to the receptor causes

conformational changes in the receptor protein. This, in turn, enzymatically activates the intracellular part of the

protein or induces interactions between the receptor and proteins in the cytoplasm that act as second messengers,

thereby relaying the signal from the extracellular part of the receptor to the interior of the cell. In this way,

integral proteins spanning the cell membrane provide a means of conveying information about the

environment to the cell interior.

Peripheral protein molecules are often attached to the integral proteins, function almost entirely as (1) enzymes

(2) controllers of transport of substances through the cell membrane “pores.

The Membrane Carbohydrates—The Cell “Glycocalyx.”

Membrane carbohydrates occur in combination with proteins or lipids in the form of glycoproteins or

glycolipids. Most of the integral proteins are glycoproteins, and about one tenth of the membrane lipid molecules

are glycolipids. The “glyco” portions of these molecules protrude to the outside of the cell, dangling outward

from the cell surface. Many other carbohydrate compounds, called proteoglycans—which are mainly

carbohydrate substances bound to small protein cores—are loosely attached to the outer surface of the cell as

well. The entire outside surface of the cell often has a loose carbohydrate coat called the glycocalyx. It has

several important functions:

(1) Have a negative electrical charge, which gives most cells an overall negative surface charge that repels other

negative objects.

(2) The glycocalyx of some cells attaches to the glycocalyx of other cells, thus attaching cells to one another.

(3) Act as receptor substances for binding hormones, such as insulin; when bound, this combination activates

attached internal proteins that, in turn, activate a cascade of intracellular enzymes.

(4) Some carbohydrate types enter into immune reactions.

Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

3

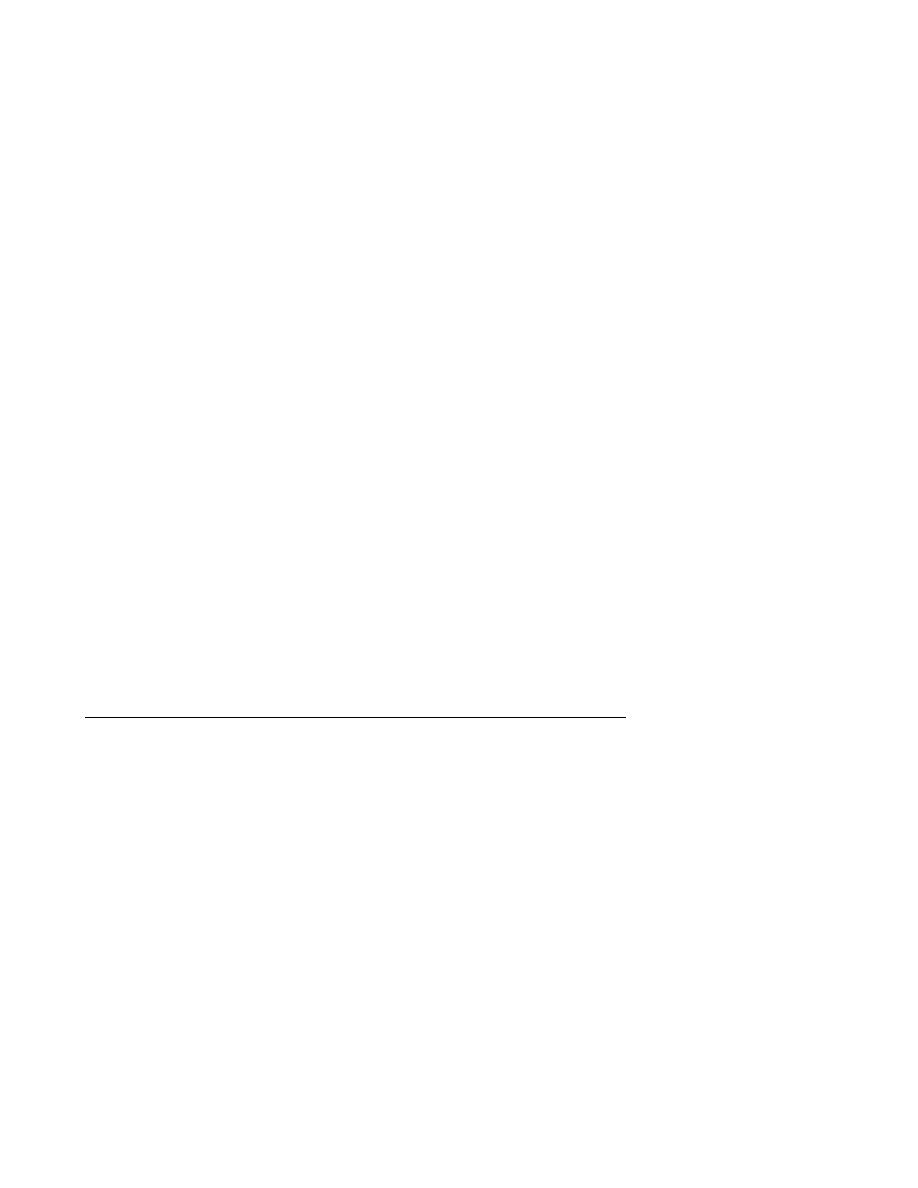

Transport through the cell membrane:

Either directly through the lipid bilayer or through the proteins, occurs by one of two basic processes: diffusion

or active transport.

Diffusion means random molecular movement of substances molecule by molecule, either through

intermolecular spaces in the membrane or in combination with a carrier protein, the energy that causes diffusion

is the energy of the normal kinetic motion of matter.

Active transport means movement of ions or other substances across the membrane in combination with a carrier

protein in such a way that the carrier protein causes the substance to move against an energy gradient, such as

from a low-concentration state to a high-concentration state, It requires an additional source of energy besides

kinetic energy.

Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

4

Diffusion through the Cell Membrane

Diffusion through the cell membrane is divided into two subtypes called simple diffusion and facilitated

diffusion. Simple diffusion means that kinetic movement of molecules or ions occurs through a membrane

opening or through intermolecular spaces without any interaction with carrier proteins in the membrane. Simple

diffusion can occur through the cell membrane by two pathways: (1) through the interstices of the lipid bilayer if

the diffusing substance is lipid soluble, and (2) through watery channels that penetrate all the way through some

of the large transport proteins.

Facilitated diffusion requires interaction of a carrier protein. The carrier protein aids passage of the molecules or

ions through the membrane by binding chemically with them and shuttling them through the membrane in this

form.

Diffusion of Lipid-Soluble Substances through the Lipid Bilayer.

One of the most important factors that determine how rapidly a substance diffuses through the lipid bilayer is the

lipid solubility of the substance. For instance, the lipid solubilities of oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and

alcohols are high, so that all these can dissolve directly in the lipid bilayer and diffuse through the cell membrane

in the same manner that diffusion of water solutes occurs in a watery solution. The rate of diffusion of each of

these substances through the membrane is directly proportional to its lipid solubility. Especially large amounts of

oxygen can be transported in this way; therefore, oxygen can be delivered to the interior of the cell almost as

though the cell membrane did not exist.

Diffusion of Water and Other Lipid-Insoluble Molecules through Protein Channels.

Even though water is highly insoluble in the membrane lipids, it readily passes through channels in protein

molecules that penetrate all the way through the membrane. Other lipid-insoluble molecules can pass through the

protein pore channels in the same way as water molecules if they are water soluble and small enough. However,

as they become larger, their penetration falls off rapidly.

Diffusion Through Protein Channels, and “Gating” of These Channels

Computerized three-dimensional reconstructions of protein channels have demonstrated tubular pathways all the

way from the extracellular to the intracellular fluid. Therefore, substances can move by simple diffusion directly

along these channels from one side of the membrane to the other. The protein channels are distinguished by two

important characteristics: (1) they are often selectively permeable to certain substances, and (2) many of the

channels can be opened or closed by gates.

Selective Permeability of Protein Channels.

Many of the protein channels are highly selective for transport of one or more specific ions or molecules. This

results from the characteristics of the channel itself, such as its diameter, its shape, and the nature of the

electrical charges and chemical bonds along its inside surfaces. To give an example, one of the most important of

the protein channels, the so-called sodium channel, is only 0.3 by 0.5 nanometer in diameter, but more

important, the inner surfaces of this channel are strongly negatively charged, These strong negative charges can

pull small dehydrated sodium ions into these channels, actually pulling the sodium ions away from their

hydrating water molecules. Once in the channel, the sodium ions diffuse in either direction according to the

usual laws of diffusion. Thus, the sodium channel is specifically selective for passage of sodium ions.

Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

5

Gating of Protein Channels.

Gating of protein channels provides a means of controlling ion permeability of the channels. It is believed that

some of the gates are actual gate like extensions of the transport protein molecule, which can close the opening

of the channel or can be lifted away from the opening by a conformational change in the shape of the protein

molecule itself. The opening and closing of gates are controlled in two principal ways:

1.Voltage gating.

The molecular conformation of the gate or of its chemical bonds responds to the electrical potential across the

cell membrane. when there is a strong negative charge on the inside of the cell membrane, this could cause the

outside sodium gates to remain tightly closed; conversely, when the inside of the membrane loses its negative

charge, these gates would open suddenly and allow tremendous quantities of sodium to pass inward through the

sodium pores. This is the basic mechanism for eliciting action potentials in nerves that are responsible for nerve

signals. The potassium gates are on the intracellular ends of the potassium channels, and they open when the

inside of the cell membrane becomes positively charged. The opening of these gates is partly responsible for

terminating the action potential.

2. Chemical (ligand) gating.

Some protein channel gates are opened by the binding of a chemical substance (a ligand) with the protein; this

causes a conformational or chemical bonding change in the protein molecule that opens or closes the gate. This

is called chemical gating or ligand gating. One of the most important instances of chemical gating is the effect of

acetylcholine on the so-called acetylcholine channel. Acetylcholine opens the gate of this channel, providing a

negatively charged pore about 0.65 nanometer in diameter that allows uncharged molecules or positive ions

smaller than this diameter to pass through. This gate is important for the transmission of nerve signals from one

nerve cell to another and from nerve cells to muscle cells to cause muscle contraction.

Facilitated Diffusion

Facilitated diffusion is also called carrier-mediated diffusion because a substance transported in this manner

diffuses through the membrane using a specific carrier protein to help. That is, the carrier facilitates diffusion of

the substance to the other side.

Facilitated diffusion differs from simple diffusion in the following important way: Although the rate of simple

diffusion through an open channel increases proportionately with the concentration of the diffusing substance, in

facilitated diffusion the rate of diffusion approaches a maximum, called Vmax, as the concentration of the

diffusing substance increases, the rate of simple diffusion continues to increase proportionately, but in facilitated

diffusion, the rate of diffusion cannot rise greater than the Vmax level. What is it that limits the rate of

facilitated diffusion?

a carrier protein with a pore large enough to transport a specific molecule partway through. It also shows a

binding “receptor” on the inside of the protein carrier. The molecule to be transported enters the pore and

becomes bound. Then, in a fraction of a second, a conformational or chemical change occurs in the carrier

protein, so that the pore now opens to the opposite side of the membrane. Because the binding force of the

receptor is weak, the thermal motion of the attached molecule causes it to break away and to be released on the

opposite side of the membrane. The rate at which molecules can be transported by this mechanism can never be

greater than the rate at which the carrier protein molecule can undergo change back and forth between its two

states.

Dr. Affan

Ezzat

Cell Physiology

Lecture one

6