Vertigo: an update on diagnosis and management

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Introduction

In the UK vertigo generally refers to a hallucination of movement; this can be either the feeling of the patient or the environment being in motion.There is no consistent definition of vertigo in the literature, but many texts use a definition along the lines of: "Any movement or sensation of movement that involves a defect, real or perceived in the equilibrium of the body."

Dizziness may result from conditions of the inner ear and non-inner ear conditions. The key to differentiating between symptoms that originate in the inner ear and those which do not is differentiating a history of vertigo from a feeling of generalised disequilibrium or presyncope. Disequilibrium is the sense of feeling off balance without any actual sensation of movement.

Presyncope is the feeling of light headedness, once again often without any sensation of movement and often accompanied by a sense of impending loss of consciousness. Such symptoms are often indicative of cerebral hypoperfusion and in patients voicing such complaints it is important to enquire about a previous cardiac history or rule out orthostatic hypotension

Each year five people in every 1000 in the UK consult their general practitioner because of symptoms that are classified as vertigo. A further 10 in 1000 are seen for dizziness or giddiness. Although not generally considered to be a disease of ageing, vestibular disorders increase in incidence with increasing age. By the age of 65, 30% of people have experienced episodes of dizziness and by the age of 80, about 70% of women and 30% of men have suffered episodes of vertigo. Children are rarely brought to medical attention because of dizziness, but when they are it is often thought to be related to migraine.

The intention is to arm the reader with a schema to understand the most common vertigo conditions. To understand how to manage the patient with vertigo you need to know the anatomy and function of the normal inner ear, this will aid in the understanding of atypical presentations.

Patients with vertigo present a particular challenge to the attending practitioner as the field of vestibular medicine is evolving, particularly due to a poor understanding of the cause of much vestibular pathology. The interested reader is therefore directed to more specialist texts if interested and it is hoped that the reference section at the end of this module would provide an appropriate starting point.

Anatomy and physiology

The inner ear consists of a series of linked, fluid filled tubes, contained within cavities (labyrinths) in the temporal bone of the skull. The inner ear is about 2 cm long and has the following parts:• Cochlea

• Vestibular system

• Utricle

• Saccule.

The vestibular system does not have to be directly stimulated to generate an afferent signal. The brain responds to afferent signals with efferent (motor) responses producing the vestibulo-ocular reflexes (VOR) and vestibulospinal reflexes (VSR).

The vestibular organs act like inertial accelerometers by detecting movement of the head and sending the information to the brain. The paired semicircular canals and the otolith organs are always active, and situated laterally within the skull.

There are three main vestibular reflexes:

• Vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) - stabilises eyes• Vestibulospinal reflexes (VSR) - stabilise body and head

• Vestibulo-vegetative reflexes (autonomic reflexes) - clinically important but poorly understood.

Semicircular canals

The three semicircular canals are set at right angles to each other, which allows them to detect rotational acceleration of the head in all three planes of space (x, y, and z). They cannot detect movements of a constant velocity - semicircular canals act like accelerometers.One of the functions of the semicircular canals is to provide afferent input for the vestibulo-ocular reflex to keep the eyes steady as the head turns. This reflex is believed to have evolved at the same time as stereoscopic vision and its main purpose is to keep an image focused on the fovea of the eye. The vestibulo-ocular reflex is necessary to enable us to see a limited visual field accurately.

The semicircular canals are curved tubes, filled with a fluid called endolymph, that contain specialised sensory regions called ampullae. These contain bundles of hair cells embedded in gelatinous coverings called cupulae. The cupulae form hydraulic seals around the ampullae. Any rotational movement of the head will result in the cupula moving in the opposite direction due to its inertia (like a driver being pushed sideways when their car goes around a sharp corner). Movements of the cupulae are transmitted to the sensory hair bundles down the eighth cranial nerve (auditory nerve).

In order that responses like the vestibulo-ocular reflex can work effectively, vestibular information must be transmitted as quickly as possible. Because of this, vestibular signals reach the brainstem without synapsing and there is a dedicated pathway (the juxtarestiform body; a division of the inferior cerebellar peduncle) for vestibular information. Efferent signals of the vestibulo-ocular reflex are transmitted along the medial longitudinal fasciculus through the third, fourth, and sixth nerve nuclei. This is the most highly myelinated pathway in the brainstem, allowing the eyes to remain steady as the head moves; and so keeping images fixed on the fovea with minimal time lag.

Otolith organs

There are two otolith organs: the utricle and the saccule. They are oriented roughly perpendicular to each other, with the utricle in horizontal plane and the saccule in vertical plane. Both organs are sensitive to linear, rather than rotary, acceleration. Within each organ, the cilia of hair cells are embedded in a gelatinous layer covered with particles of calcium carbonate. This is called the otolithic membrane, and the mineral particles are called otolithsThe otolith organs provide two kinds of spatial information, both of which are important components of the vestibulospinal reflexes. They detect:

Straight line movement of the head due to horizontal or vertical acceleration

The static position of the head, for example in positions such as bending over.

Both forms of spatial information are transduced into signals which pass down the eighth cranial nerve to the brainstem nuclei.

Information from the otoliths drives the vestibulospinal reflex, which synapses down the spinal cord, probably to the lumbar level. In this way, both the head and the body can be stabilised. Information from the neck also seems to feed into the vestibular system, which may explain why some patients with whiplash injuries can present with vestibular symptoms. But the mechanism for this is poorly understood.

Autonomic reflexes

These are important but poorly understood. Vestibular stimulation can cause nausea and sweating, as well as emotional responses such as anxiety and panic. Panic reflexes and anxiety related to vestibular pathology are not due to psychiatric disease, but are part of the vestibular symptom set, driven by brainstem responses.History and examination

Assessing the dizzy patientIn the 1963 edition of Practical Neurology, Matthews explained how treating patients with dizziness can go wrong: "There can be few physicians so dedicated to their art that they do not experience a slight decline in spirits when they learn that their patient's complaint is dizziness. This frequently means that after exhaustive enquiry it will still not be entirely clear what it is that the patient feels wrong and even less so why he feels it."

In order to avoid this unsatisfactory and frustrating experience, you must begin by taking an accurate, complete, and non-leading history from the dizzy patient.

It is important to recognise that a patient's symptoms may be atypical but these symptoms may be genuine. If the symptoms are subtle or unusual sounding (eg "I feel like I'm on a boat all the time"), it is possible that a patient may be reluctant or embarrassed to voice their complaints. Or they may be worried that you will not believe them, as they may well have previously been dismissed by others.

Probably one of the greatest shortcomings of vestibular diagnostics is the lack of an international classification of vestibular disorders (in addition to the ambiguity of the term vertigo, as discussed earlier). A committee of international experts is presently working on agreeing definitions of key vestibular syndromes, in the hopes of laying the groundwork for standardising terms and symptoms, but this is not yet in place.8 The most useful advice we can give at present is to emphasise the importance of taking a careful history.

The following clinical protocol is based on the authors' clinical experience; with experience you may develop your own method of enquiry. As further clinical research is conducted, more evidence based guidelines may become available.

1. Symptoms of dizziness:

When did the symptoms start?

Describe the symptoms

You should ask open questions, like "Tell me what it feels like"

Avoid leading questions (which suggest an answer) like "Do you feel like the room is spinning?", which suggests the answer "Yes, I do doctor"

If the patient has difficulty expressing themselves (for example if the clinic is being held in a language other than their own) patients will often make a gesture of rotating a finger around their head or indicate a revolving spinning motion with their hand. In the authors' experience this non-verbal sign is strongly suggestive of unilateral vestibular disease

Time course: is it worsening, resolving, or fluctuating?

Persistence: is it constant or occurring in episodes?

Quantify episodes (length, frequency, etc). Patients with vertigo often find it difficult to make accurate estimates of time, so reports from family members can be helpful

Are there any associated symptoms, such as:

NauseaAnxiety

Neurological symptoms

Are episodes spontaneous or provoked (eg by head movements)?

2. Do the symptoms go away completely between episodes? In the authors' experience it is important to be emphatic about this, for example by asking "Are you the same as you were before the dizziness started?" If the patient gives an equivocal answer it may mean that they are compensating for the symptoms

3. Are there any new associated symptoms, such as fear of heights or motion sickness?

4. Are there any signs of dizziness, such as bumping into stationary objects? It is often helpful to question family members, for example, they may say: "He bumps into me when we go for a walk." However, the absence of physical signs does not rule out disease.

5. History of ear symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss, pain, discharge)

6. Neurological symptoms7. Ophthalmological symptoms

8. Family history

9. Other risk factors for inner ear disease, such as:

Head injury

Ototoxic medication

Whiplash injury.

Examination

Unfortunately there are few reliable clinical signs to detect or rule out vestibular disease, including the time honoured Romberg test.However, there are some subtle techniques that can be used with patients with complaints which may arise from the vestibular system.

You can begin your assessment as soon as you meet a patient in the waiting room. A patient capable of carrying on a conversation while walking is quite likely to have reasonable balance. You may wish to observe the patient while walking along several adjoining hallways, making abrupt turns both to the right and left, and traversing an uphill and downhill incline. A patient with a vestibular deficit will often stare at the floor to keep their balance, especially in an unfamiliar setting such as a hospital.

When patients with vestibular pathology walk, they often veer towards the side of the lesion, and use a wide based gait. You should be wary of patients who try to "show you how bad my balance is" by using a narrowed base of gait (tightrope walking) or swaying excessively when standing still.

The following list of examination techniques is by no means prescriptive, but is, in the authors' experience, useful when examining a patient with vertigo. They are based on a neuro-otological examination as outlined by Goebel1 and Bronsteinand the interested reader is referred to these texts for more detailed information.

Ears - otoscopy of both ears, tuning fork tests of hearing

Eyes - examine eye movements for saccades, smooth pursuit, and nystagmus - spontaneous and gaze evoked

Central nervous system - examine cranial nerves and look for cerebellar signs

Vestibulo-ocular reflex tests:

Vestibulo-ocular reflex tests:

You can quickly assess the responsiveness or gain of a patient's vestibulo-ocular reflexes by asking them to read letters on a fixed object (like a newspaper) while they shake their head from side to side. This can be tested more formally using the Dynamic Illegible E test (DIE test)Asymmetrical vestibulo-ocular reflexes are helpful in diagnosing vestibular neuritis, or tumours such as vestibular schwannomas, and to rule out functional disorders. But these tests are usually performed in specialist neurotology clinics and are outside the scope of this module.

These specialist tests include:

• Head-shake test• Head-impulse test (Rapid Dolls)

• Manoeuvres which evoke nystagmus, such as the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre, are helpful for diagnosing benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

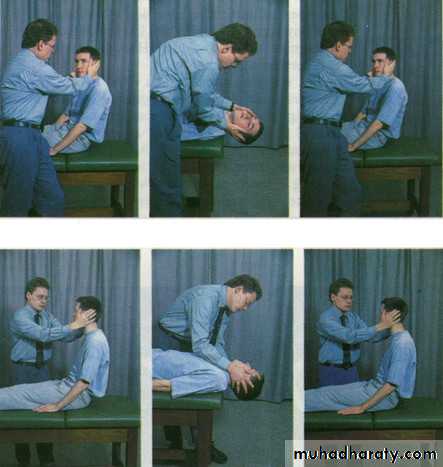

Learning bite: Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre

This manoeuvre is used as a diagnostic test, used particularly when you suspect benign paroxysmal positional vertigoYou should explain the procedure to the patient, and warn them that they may experience vertigo symptoms during it, but that the symptoms usually subside quickly. You should ask them to keep their eyes open throughout and stare at your face. Check that the patient does not have any neck injuries or other contraindications to rapid spinal movements

Ask the patient to sit on an examination couch with their legs extended, close enough to the edge so that their head will hang over when they are laid flat

Stand on their left side, take hold of their head with both your hands, and turn their head 45° towards you. (This tests the left posterior canal). Observe their eyes for 30 seconds. (Signs and symptoms usually occur when you turn the patient's head towards the lesion - if you suspect disease of the right ear, you may wish to start on their right side.) I personally would start with the non-affected side

Keeping the patient's head in the same position, lie them down quickly until their head is hanging over the edge of the couch (still turned 45° towards you) Observe their eyes for 30 seconds

Lift the patient back up to sitting position, and repeat the test on their right side

In a patient with BPPV, you will typically see a characteristic pattern of nystagmus emerge after 5-20 seconds, when the patient's head is hanging towards the side of the lesion. This is called torsional or rotatory nystagmus and has two components: a quick movement towards the side of the lesion and a slow component away from it.

An upward beating nystagmus is often superimposed on this movement.

Figure 1. Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre (with permission BMJ publishing Lempert et al 1995)

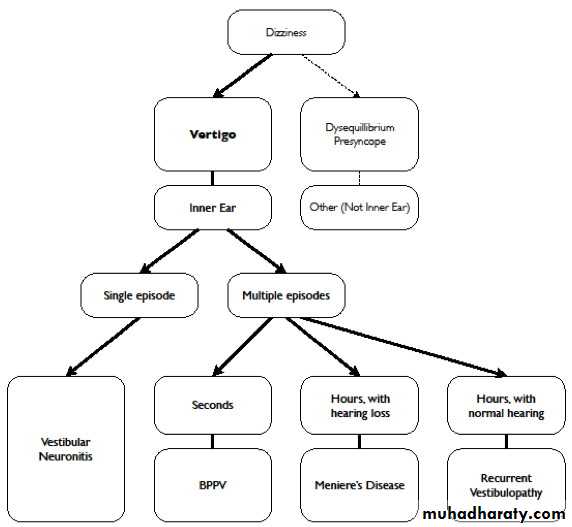

Figure 2: A schema for thinking about diagnosis of patients with vertigoWhen considering how to manage a patient presenting with vertigo it is often useful to have a framework to focus your mind. As we have already emphasised, a good history is invaluable, and if you suspect that the patient's symptoms are not true vertigo, it is important to exclude causes of symptoms which are commonly confused, such as presyncope and disequilibrium.

Common conditions

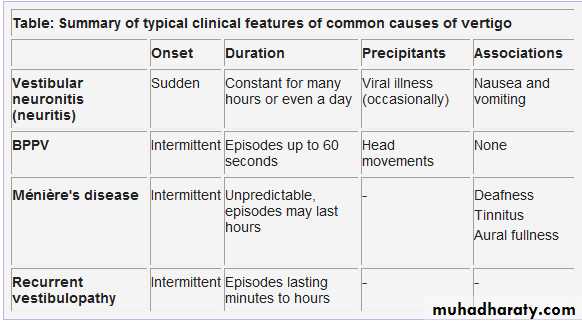

Vertigo is usually caused by dysfunction of the inner ear and four diagnoses account for the majority of patients presenting to a GP or an ENT clinic. These are:• Vestibular neuronitis

• Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

• Ménière's disease

• Recurrent vestibulopathy

Vestibular neuronitis

Example case history: A 34 year old builder had been feeling non-specifically unwell for a few days before experiencing a sudden, severe, and unrelenting attack of vertigo. He awoke one morning to find the room appeared to be spinning violently around him. He felt absolutely awful and was extremely nauseated. He tried to eat but for the whole day food just made him vomit. During the next day the vertigo began to subside but for the week following he felt very off balance.Vestibular neuronitis is really a misnomer, and the condition is more accurately referred to as acute vestibulopathy. The cause of vestibular neuronitis is unknown, however it has been suggested that it may be the result of a viral infection. Vestibular neuronitis is diagnosed in about 5% of patients referred to a dedicated dizziness unit.

Typically patients with vestibular neuronitis present with symptoms of vestibular disturbance alone, but other structures of the inner ear can also be involved, and patients may also describe hearing loss and tinnitus (sometimes called acute labyrinthitis). This can be useful as this may assist the clinician in lateralising the pathology to one ear. Some patients suffer from recurrent episodes of the condition (recurrent vestibulopathy).

Learning bite: vestibular neuronitis

You need to assess patients who suddenly lose their hearing, with or without vertigo, as an emergency. You should arrange an audiological assessment to differentiate between a conductive and a sensorineural hearing loss; and arrange a brain MRI scan for patients with a sudden onset of asymmetrical hearing loss which is sensorineural, to exclude a vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma).If seen early (within seven days) the patient may be offered a course of oral steroids, however, good evidence to support the use of steroids is sadly lacking. Other treatments may be offered in different ENT departments, so if the patient presents early a conversation with your local ENT department may be useful.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

Example case history: You see a 43 year old man in your clinic. For the past few weeks he has noticed that he gets "the spins" when he tilts his head upwards to reach onto high shelves. His symptoms never last longer than 30 seconds, and are always provoked by head movements such as this. He was referred to his local ENT specialist who took a detailed history and performed a full neurological examination.The ENT specialist performed a Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre and found that moving the patient's head whilst in the left, lateral position elicited a rotatory nystagmus. The characteristics of the nystagmus were:

It did not come on immediately; there was a delay of a few seconds

It was rotatory and directed towards the ground

After a while it slowed down and then stopped

Upon repeating the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre, it was much less severe.

These features were typical of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The specialist performed the Epley manoeuvre (a canalith repositioning manoeuvre), and at review six weeks later, all of his symptoms had completely resolved. A repeat Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre was performed but this time it did not elicit any nystagmus.

As the name suggests, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is a self limiting disorder and resolves spontaneously often lasting no longer than a few months.

Patients describe episodes of vertigo lasting for up to a minute, usually precipitated by certain head positions. It is thought to be the result of otoconial debris collecting in one of the semicircular canals and stimulating the canal when head movements are directed along the same plane as the canal. This condition most often affects the posterior semicircular canal, which detects movement in the saggital plane, but rarely either of the other two semicircular canals can be affected.

Learning bite: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Positional nystagmus can be a feature of cerebellar dysfunction, so you should conduct a full neurological examination. Be certain that the characteristics of the nystagmus fit those typically described for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo before making this diagnosis.Ménière's disease

Example case history: You see a 51 year old housewife who has now had her third attack of vertigo within the last three months. The first attack came unexpectedly when she was preparing lunch, and lasted several hours. She remembers this attack was associated with severe nausea and she vomited a number of times. She has noticed mild hearing loss over the last year in her right ear, associated with mild tinnitus. During a vertigo attack she is completely incapacitated. She cannot recall any change in hearing during episodes, but she does describe that her right ear feels plugged up.Ménière's disease is characterised by a triad of:

VertigoHearing loss

Tinnitus.

Patients also often describe an associated sensation of their ear canal feeling full. Patients may not describe all of the typical features and symptoms may vary, especially in the early stages of the disease.

The American Academy of Otolaryngologists and Head and Neck Surgeons has produced diagnostic guidelines for Ménière's disease. There is no single reliable diagnostic test and Ménière's disease is probably over diagnosed by non-specialists.

In brief, the AAO-HNS guidelines stipulate that a definite diagnosis of Ménière's disease can only be made when all three of these criteria are present:

At least two spontaneous episodes of rotational vertigo lasting at least 20 minutes

Audiometric confirmation of a sensorineural hearing loss

Tinnitus and/or a perception of aural fullness.

Although these criteria exclude most other vestibular conditions, they cannot exclude non-vestibular diseases such as the presence of a vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma).

Learning bite: Ménière's disease

The management of the patient who you think may have Ménière's disease is complex and if possible you should refer these patients to an ENT surgeon with a special interest in balance disorders. A variety of drugs have been used to treat Ménière's disease, including anticholinergics, vestibular sedatives, and betahistine, but there is no evidence that any of these are effective.

The diagnosis, investigation, and treatment of these patients are controversial and continuingly evolving.

Recurrent vestibulopathy

Example case history: A 35 year old businessman comes to your clinic. For the last six months he has had recurrent bouts of vertigo lasting for 30 to 90 minutes. These are severe enough for him to have to leave work but apart from the sensation of spinning and the associated nausea he describes no other symptoms.The term recurrent vestibulopathy is used to describe recurrent vertigo with episodes which last from five minutes to 24 hours, which occur in the absence of auditory or neurological symptoms or signs. The spells occur spontaneously, without a prodrome and are not provoked by particular movements.

The clinical course of patients with recurrent vestibulopathy has been studied. The majority of these patients (about 70%) retain the original diagnosis. The majority of these patients suffer from vertigo occurring less than once yearly. Of the remaining patients, another condition is often diagnosed; this is known as diagnostic conversion and patients usually convert to either Ménière's disease or BPPV. The underlying mechanism in patients who do not undergo diagnostic conversion, but remain RV active is unknown (10% of patients overall). Some authors have suggested that recurrent vestibulopathy might be a migraine-like phenomenon, but this has recently been disputed.

Learning bite: recurrent vestibulopathy

With this diagnosis, the best treatment is often "tincture of time" (in other words, reassure the patient and review) as recurrent vestibulopathy may settle spontaneously. Where the condition does not settle, similarly to patients with Ménière's disease, these patients may require long term follow up by an ENT surgeon with a specialist interest in balance disorders.The diagnosis, workup, and treatment of these patients is controversial and continuingly evolving because the underlying cause of this condition is uncertain.

Non-vestibular causes of vertigo: a word of caution

You should be aware of red flag symptoms, which may indicate more serious disease, in patients with vertigo. Examples include symptoms specific to abnormalities of either the neurological or cardiovascular systems and certain patient groups will be at a higher risk than others. Symptoms of common causes of vertigo tend to be self limiting, because either the pathology resolves or the patient develops compensatory mechanisms; patients are usually completely well between attacks.Less common conditions can present with vertigo or similar symptoms, and the key to not being caught out is often obtained from taking a thorough and focused history and performing an appropriate physical examination. If in doubt, you should seek advice from your local ENT surgeon, neurologist, or medical physician.

Less common, but more serious, conditions which can present with vertigo include:

Cerebrovascular eventsCerebrovascular events (strokes) can affect the brainstem resulting in vestibular symptoms due to involvement of the vestibular nuclei. You need to manage patients with brainstem or cerebellar signs urgently, as some causes of central vertigo can be life threatening.

Brainstem tumours

You should consider the possibility of a brainstem tumour in patients who present with atypical features such as persistent vertigo or asymmetrical cochlear symptoms, such as hearing loss and/or tinnitus in one ear only. Imaging of the brain (particularly the cerebellopontine angle) should be performed in these circumstances.Cerebellar pathology

The cerebellum is responsible for balance maintenance, control of visual movements, and the vomiting response. Because of this, cerebellar lesions can masquerade as vestibular pathology. You should consider differentials such as ependymoma, cerebellar metastasis, or Arnold-Chiari malformation.A particularly reliable sign of cerebellar pathology is downbeat nystagmus, which suggests pathology at the cranio-cervical junction. If you see this sign in a patient, imaging of their posterior fossa with MRI (or CT if MRI is not available) should be considered. When requesting a scan, sufficient views of the cerebellar tonsils are required to rule out an Arnold-Chiari malformation.

Other investigations

AudiometryDue to the intimate relationship between the balance system and hearing within the inner ear, ENT specialists will arrange an audiogram for all patients they see with vertigo. An audiogram is valuable to:

Help to make a diagnosis

Follow disease progression

Clarify which ear is affected.

It can be unclear which ear is affected and degree of hearing disability is of particular importance when considering destructive treatments for patients with conditions such as Ménière's disease.

Specialist tests of the vestibular reflexes

Many expensive and time consuming specialist tests exist, but their use in the typical patient with vertigo is questionable. For the majority of patients specialist tests are unnecessary and add little to a good history and examination. They are useful in limited circumstances, for example if a specialist is planning to perform a destructive neuro-otological procedure. Most non-specialists will not be expected to have detailed knowledge of these tests; they are included here together with an explanation of the science behind their application.

Vestibulo-ocular reflex

The vestibulo-ocular reflex coordinates eye and head movements, so that humans do not usually experience blurring of images when they move their heads. Patients with unilateral lesions experience vertigo because of asymmetrical afferent signals into this reflex.Bilateral loss of vestibular response can result in blurred vision with head movement (called oscillopsia) but does not result in vertigo. Such patients may complain of being unable to read the signs on shops when they are walking. Bilateral pathology is very rare. It can be caused by such conditions as gentamicin toxicity or syphilis.

Caloric testing

The vestibulo-ocular reflex is tested using the caloric test, as described by Barber and Stockwell This involves irrigating warm, and then cool, water into the patient's ear canal. The standard method is to use 250 ml of water at 44ºC and 250 ml of water at 30ºC, each instilled over a 30 second period. Heat is conducted to the semicircular canal, causing convection currents in the endolymph. This simulates circulation of endolymph which occurs during head movement, and activates the vestibulo-ocular reflex, causing the patient's eyes to move in response. The eyes are quickly re-centred by the brain and the process is repeated, leading to a repetitive cycle of eye movements called nystagmus. This movement has two phases: a slow phase, generated by the vestibulo-ocular reflex; and a fast phase, controlled by the cortex.The normal range of eye movement responses is from 11-80º per second for warm water and 6-60º per second for cool water. The total range of eye movement from stimulation of one ear is compared to the total of the other ear; and the difference is expressed as a percentage. Results must be symmetrical within a margin of error of 25% to be classified as normal, but a normal caloric test does not rule out pathology. Abnormal results can lateralise symptoms and also are useful in eliciting a patient's symptoms. If the test reproduces the patient's symptoms this confirms that they probably arise from the vestibular system.

Vestibulo-spinal reflexes

Under normal circumstances, patients are able to keep their balance using information from their vestibular system alone. They do not need additional information, such as vision or somatosensory information. Patients with deficits in the vestibulo-spinal reflexes will report vague unsteadiness and often characterise their complaints based on past experience, for example, they may describe a feeling "like I'm on a boat" or "like I've had a little bit too much to drink."Testing the vestibulo-spinal reflexes

In 1841 Romberg developed a standing test to measure sway in patients with syphilis. He found that patients with tertiary syphilis often became unsteady when they closed their eyes. Although Romberg's original use of this test actually measured dorsal column function, it is a useful clinical test of vestibulo-spinal reflexes. Although it is still in clinical use today, Romberg's test is not very specific (many people with normal vestibular systems have a positive test).Computerised dynamic posturography testing was developed by Lewis Nashner in 1982to try to measure vestibulo-spinal reflexes more reliably. This technique measures how far a standing patient's body sways under various conditions. A normal person can sway within a cone of support by about 12º without losing their balance. The total amount of sway is quantified under a variety of sensory deprivation conditions, which measure the ability of the vestibulospinal system to maintain balance without assistance from other sensory input. Posturography is more sensitive and informative than standard clinical testing, but the equipment is expensive.

Treatment of conditions causing vertigo

Acute vertigoThe treatment of an acute vertigo attack, such as occurs in an acute vestibular neuronitis or a Ménière's attack is medical. A variety of vestibular sedatives can be used in the short term, such as prochlorperazine or cinnarizine. You should not prescribe these drugs for longer than a few days because they can cause sedation and psychomotor impairment, which impedes central compensation. Patients suffering from acute vertigo often need vestibular rehabilitation and the use of vestibular sedatives will retard this process.

Vestibular rehabilitation

In patients with a stable vestibular loss, vestibular rehabilitation is the mainstay of treatment. There are several formal techniques for rehabilitation, which are beyond the scope of this module, but informal rehabilitation is likely to be effective in many patients. You should encourage patients to take up regular physical activities, which may involve playing sports or other forms of exercise such as yoga. A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was moderate to strong evidence that vestibular rehabilitation is a safe, effective management for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction

One of the authors (JP) explains the basis of this to patients using the analogy of flying an aeroplane with only one working engine. Vestibular rehabilitation works using a number of mechanisms but neural plasticity aids the "pilot" in compensating for the loss of one of the "engines." Some patients believe that inducing their symptoms will worsen their situation, when actually it is the reverse which is usually true.

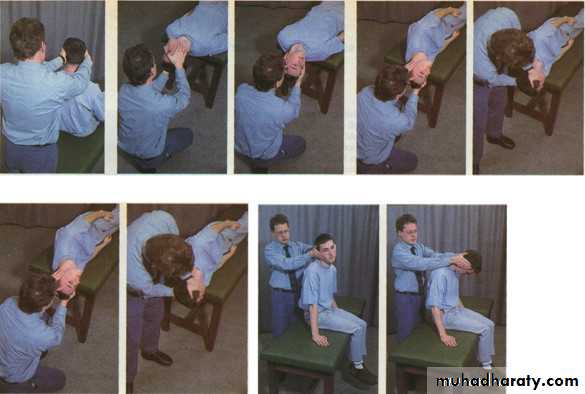

Particle positioning manoeuvres

A number of particle positioning manoeuvres exist to treat benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. A Cochrane review concluded that the Epley manoeuvre is a safe and effective treatment,22 Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is a common condition, so it is worthwhile learning how to perform the diagnostic Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre and the therapeutic Epley procedure. If you make the correct diagnosis and successfully cure a patient of their vertigo, they will never forget you.Learning bite - the Epley manoeuvre: a canalith repositioning procedure

A recent systematic review concluded that canalith repositioning procedures like the Epley manoeuvre are generally safe and effective for patients with BPPV.23It is thought to work by rotating the posterior canal backwards, and so directing particulate material out of the canal into the utricle.

You should perform each manoeuvre and hold it until any positional nystagmus has disappeared: this indicates that the movement of endolymph has stopped. You may need to repeat the whole procedure three or four times, until nystagmus no longer appears.

You should explain the procedure to the patient, and warn them that they may experience vertigo symptoms during it, but that the symptoms usually subside quickly. You should ask them to keep their eyes open throughout. Check that the patient does not have any neck injuries or other contraindications to rapid spinal movements - you need to execute movements during the procedure rapidly (in less than one second)

Ask the patient to sit on an examination couch with their legs extended, close enough to the edge so that their head will hang over the edge when they lie down. Stand behind the patient and hold their head in both of your hands

Turn the patient's head 45° towards the affected ear, keeping their head in that position, lean the patient back rapidly until their head is over the edge of the couch. Hold until nystagmus dissipates

Rotate the patient's head through 90°, so that it is facing 45° away from the affected ear, then (keeping their head steady, still hanging back over the couch edge) ask the patient to roll their body to straighten their neck. Hold .Ask the patient to keep their body still, while you turn their head 45° to face the floor. Hold.While keeping the patient's head turned to the side, help them to sit up.

With the patient sitting up, move their head into the centre line, as you move it forward 45° (chin on chest).

Figure 3: Epley Procedure (with permission BMJ publishing Lempert et al 1995)

Management of Ménière's diseaseThe management of patients with Ménière's disease is challenging because its cause remains unknown. It is important that you arrange for these patients to be assessed by a specialist. The evidence base for management of patients with Ménière's disease is sadly lacking, making it difficult to choose which drugs or other techniques to offer.24 The pros and cons of these treatments are beyond the scope of this module.

Most common causes of dizziness either cause vertigo for a few days, which gradually settles (vestibular neuronitis) or episodic vertigo. Unremitting vertigo for more than a few days should make you consider a non-vestibular cause. Asymmetrical cochlear symptoms such as these should make you consider a cerebellopontine angle tumour.

Downbeat nystagmus is a sign of cerebellar disease, and suggests pathology at the cranio-cervical junction. You should consider differentials such as ependymoma, cerebellar metastasis, or Arnold-Chiari malformation.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, which is thought to be due to debris collecting in one of the semicircular canals and stimulating the canal when head movements are directed along the same plane as the canal.

Computerised dynamic posturography is a method for testing the vestibulo-spinal reflex by measuring how much a patient sways under a variety of sensory deprivation conditions, so testing their ability to maintain balance without assistance from other sensory inputs.

Epley manoeuvre

The Epley manoeuvre is a canalith repositioning procedure. A recent systematic review concluded that canalith repositioning procedures like the Epley manoeuvre are generally safe and effective for patients with BPPV.It is thought to work by rotating the posterior canal backwards, and so directing particulate material out of the canal into the utricle.

Patients with a lesion affecting just one vestibulo-ocular reflex will present with vertigo due to the asymmetrical sensory input.

Patients with a lesion affecting both vestibulo-ocular reflexes are unable to coordinate movement of their head and eyes, called oscillopsia, but do not usually complain of vertigo.

The vestibulo-spinal reflex helps to coordinate head and body movement, but it is not involved in stabilising vision.

الضبابعلمني الضباب ان الانسانقد يمر بلحظات عصيبةومصائب وأزماتلكن لابد أن ياتي الفرج من اللهويعود كل شي كما كان