Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Key points

Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar non-ketotic state (also known as hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state) are diabetic emergencies within a spectrum of hyperglycaemic statesDiabetic ketoacidosis is more common than hyperosmolar non-ketotic state, but hyperosmolar non-ketotic state has a higher mortality than diabetic ketoacidosis.

About 10% of people diagnosed as having non-obesity related type 2 diabetes may have latent autoimmune diabetes in adults.(LADA)

This term was introduced to define patients with adult onset diabetes who initially do not require insulin but who have immune markers of type 1 diabetes and in some cases progress to insulin dependency.

LADA Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults

has also been referred to as late onset autoimmune diabetes of adulthood, slow onset type 1 diabetes, and type 1.5 (one and ahalf) diabetes. It is defined by three features:adult age at diagnosis, presence of diabetes associated autoantibodies, and delay between diagnosis and the need for insulin to manage hyperglycaemia. Patients who develop diabetes in adulthood (with and without autoantibodies) vary in age of onset and phenotype and are therefore difficult to distinguish from each other.

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults should be suspected when features of the metabolic syndrome are lacking,hyperglycaemia is uncontrolled despite the use of oral agents,and there is evidence of autoimmune diseases.

The presence of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase is a sensitive and specific marker for future insulin dependency in patients with latent type 1 diabetes. A high titre of these autoantibodies may be predictive of early insulin requirement. Other diabetes associated autoantibodies such as islet cell autoantibodies may also be present.

About 80% of adults initially diagnosed with type 2 diabetes who have antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase need insulin therapy by six years, compared with 14% of patients without these antibodies. There is no established management strategy for patients diagnosed with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. So far, no therapeutic measures have been shown to prevent or delay insulin requirement in this subgroup of patients.

It may be advisable to avoid metformin in these patients because of the theoretically increased risk of metabolic acidosis and to start insulin early to prevent episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis.

DKA usually occurs as a consequence of absolute or relative insulin deficiency that is accompanied by an increase in counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, and adrenaline, which leads to hyperglycaemia and ketosis. Hyperglycaemia develops as a result of increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, accelerated glycogenolysis, and impaired glucose use by peripheral tissues. Lipolysis is enhanced, with the release of free fatty acids into the circulation, and unrestrained hepatic oxidation of these free fatty acids leads to increased formation of ketone bodies and subsequent metabolic acidosis. The hyperglycaemia induced osmotic diuresis depletes sodium, potassium, phosphate, and water.

Serum potassium may be normal or even raised because of the extracellular shift of potassium caused by insulin deficiency,

hypertonicity, and acidaemia, so serum potassium poorly reflects the patient’s total potassium stores.

DKA consists of the biochemical triad of

ketonaemia (≥3 mmol/L) or severe ketonuria (more than 2+ on standard urine sticks),hyperglycaemia (blood glucose >11 mmol/L), and

acidaemia (bicarbonate <15 mmol/L or venous pH <7.3, orboth).

Patients with severe DKA and reduced

consciousness should be admitted to an intensive care unit orhigh dependency unit.

A priming dose of insulin in the treatment of DKA is not needed if the insulin infusion is started promptly at a dose of at least 0.1 U/kg/h. The Joint British Diabetes Societies Inpatient Care Group on the management of DKA has recently recommended that the “sliding scale” insulin should be replaced with weight based fixed rate intravenous insulin infusion. A rate of 0.1

U/kg/h is recommended. The fixed rate may need to be adjusted in insulin resistant states if the ketone concentration does not fall fast enough or the bicarbonate concentration does not rise

fast enough (or both).

To prevent recurrence of hyperglycaemia or ketoacidosis during the

transition period, allow an overlap of one to two hours between discontinuing intravenous insulin and starting subcutaneous insulin.

To prevent hypokalaemia, start potassium replacement once serum concentrations fall below the upper level of normal. Potassium should be maintained at 4.0-5.0 mmol/L.The use of bicarbonate in DKA is controversial. Adequate

fluid and insulin therapy will resolve the acidosis and the use of bicarbonate is discouraged, although some guidelines recommend small amounts for severe acidosis (pH 6.9-7.0) and

large amounts for extreme acidosis (pH <6.9)

Whole body phosphate deficits in DKA are substantial, but

evidence of a benefit from phosphate replacement is lacking,and the routine measurement or replacement of phosphate is not recommended.

However, in the presence of respiratory and

skeletal muscle weakness, phosphate measurement and replacement should be considered.

Resolution of DKA is defined as blood ketones less than 0.3 mmol/L and venous pH greater than 7.3.

Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of DKA, with close monitoring and correction of electrolytes, has greatly reduced overall mortality from this life threatening condition.

Hypoglycaemia and hypokalaemia are common complications with overzealous treatment of DKA with insulin and bicarbonate, respectively, but they are less common with low dose insulin therapy.

The main causes of death in the adult Diabetic ketoacidosis

population include severe hypokalaemia; adult respiratory distress syndrome; and comorbid states such as pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, and sepsis. Pulmonary oedema has been reported only rarely in DKA. Elderly patients and thosewith impaired cardiac function are at particular risk, and monitoring of central venous pressure should be considered.

Cerebral oedema is the most common cause of death in young children and adolescents, but it is rare in adults during treatment of DKA. Cerebral oedema is associated with a mortality rate of 20-40%.

Diabetic ketoacidosis occurs mainly in patients with type 1 diabetes

The diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis requires ketosis and acidosis (pH <7.3). Serum glucose and osmolality are variable

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is a severe hyperglycaemic state and occurs mainly in older patients with type 2 diabetes

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is defined as hyperglycaemia and hyperosmolality in the absence of acidosis and without strong ketonaemia

Clinical tips

You should routinely measure blood glucose and electrolytes in all sick, drowsy patients who present to hospital to exclude or diagnose diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar non-ketotic state .Dehydration is more life threatening than hyperglycaemia in patients with hyperglycaemic emergencies. Rehydration is therefore the most important and urgent step.Make sure patients with diabetic ketoacidosis learn the "sick day rules" so they will not have further episodes.Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis is severe, uncontrolled diabetes with elevated ketone levels requiring urgent treatment with intravenous fluid and insulin. Diabetic ketoacidosis is common. It affects 1-5% of patients with type 1 diabetes per year. Although diabetic ketoacidosis typically complicates type 1 diabetes, it can also occur in patients with type 2 diabetes if an acute illness results in severe insulin deficiency. Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis typically have a two to three day history of lethargy, malaise, and vomiting.Drowsiness indicates that ketoacidosis is severe.

Causes and diagnosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis follows severe insulin deficiency. This causes hyperglycaemia (due to lack of insulin mediated uptake of glucose from the circulation into skeletal muscle) and formation of ketone bodies (due to lipolysis normally inhibited by insulin). The hyperglycaemia causes an osmotic polyuria. Hyperglycaemia also impairs gastric emptying, predisposing to vomiting. Dehydration ensues and this is worsened by acidosis caused by elevated levels of the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate.Diabetic ketoacidosis can be the first presentation of a new diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.

Precipitants of diabetic ketoacidosis include conditions that increase insulin requirements, such as:

Infection

Surgery

Myocardial infarction.

Failing to increase the dose of insulin causes insulin deficiency that leads to hyperglycaemia and acidosis. The insulin deficiency is exacerbated if insulin is deliberately reduced or omitted because of an inappropriate fear of hypoglycaemia. Deliberate omission of insulin may explain why some patients have recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis. Neuroleptic drugs, particularly atypical antipsychotic drugs such as olanzapine, are increasingly recognised as contributors to new onset diabetes that may present as diabetic ketoacidosis.

The diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis is clinical. The main signs and symptoms are:

Polyuria,Polydipsia

Lethargy,Anorexia

Hyperventilation,Ketotic breath

Dehydration,Vomiting

Abdominal pain

Drowsiness/coma.

For audit and research we recommend you diagnose diabetic ketoacidosis in a sick person with:

Diabetes

Metabolic acidosis (bicarbonate levels ≤15 mmol/l)

Hyperketonaemia (urine test stick reaction at least ++ or plasma test stick reaction at least +).

You should confirm the diagnosis by measuring:

Plasma glucose - diabetic ketoacidosis presents with a variable blood glucose that is rarely below 10 mmol/l but sometimes only minimally elevatedElectrolytes - measure sodium and potassium to exclude hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

Diabetic ketoacidosis is associated with severe potassium depletion. This can be masked by leakage of potassium from red cells into the circulation

Arterial blood gases – although venous blood is adequate for measurement of pH and bicarbonate, an initial arterial sample is helpful to assess gas exchange.

Assess hyperketonaemia by stick testing the patient's blood or urine. Fingerstick glucose measurements rapidly estimate hyperglycaemia, but their accuracy is limited especially when hyperglycaemia is severe. Measuring the plasma glucose is therefore important.

Arterial blood gas sampling is mandatory, at least in the initial phase, because it provides information about gas exchange in critically ill patients and can measure potassium. The table shows the biochemical criteria for diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperosmolar non-ketotic state.

Table. Biochemical criteria for diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic stateSerum glucose

Elevation is variable

At least 30 mmol/l

Serum bicarbonate

15 mmol/l or less

Above 15 mmol/l

Urine ketones

(Test sticks measure acetoacetate, which is converted from 3-hydroxybutyrate)

At least ++

+ or less

Osmolality (calculated from 2 x ((Na+) +(K+)) +(urea) + (glucose))

Variable

At least 340 mmol/l

To look for possible precipitating illnesses you should take:

• A chest x ray• An electrocardiogram

• Cultures of blood, urine, and sputum

Some sick patients with diabetes will have other, possibly coexisting, causes of acidosis, for example:

Renal failure

Pulmonary oedema

Sepsis

Metformin toxicity causing lactic acidosis

Salicylate poisoning.

You should consider these possibilities during the clinical assessment

Managing diabetic ketoacidosis

Remember that any ill patient with diabetes presenting with elevated ketones needs urgent treatment. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis consists of:• Careful attention to hydration

• Correcting serum potassium

• Correcting insulin deficiency

• Managing any precipitating illness.

Management protocols for diabetic ketoacidosis are well described. It is recommended that all hospitals have guidelines for diabetic emergencies. You should familiarise yourself with your local guideline. It will include recommendations about:

Fluid replacement

Insulin replacement

Serum potassium replacement

General measures and monitoring.

Fluid replacement

This consists of infusion of 1-2 litres of 0.9% saline over 1-2 hours, usually followed by another 4-8 litres of fluid during the next 24 hours to ensure adequate rehydration. Most authorities recommend continuing 0.9% saline until fingerstick glucose levels fall below 15 mmol/l. Intravenous dextrose (5% or 10%) is recommended at this point.

In patients with diabetic ketoacidosis with only minimal elevation of blood glucose you should give both 0.9% saline and 5% dextrose concurrently to aid adequate insulin and isotonic fluid treatment. If you check blood gases after resuscitation with several litres of fluid you may find a persistent base deficit. This is likely to represent hyperchloraemic acidosis due to the large amount of chloride given. This resolves spontaneously and is not an indication for further fluid resuscitation.

Insulin replacement

This involves intravenous infusion of soluble insulin. Giving an initial dose of intramuscular insulin (20 units) ensures prompt treatment while you set up an infusion pump. Most authorities recommend continuing a fixed rate of insulin at a rate of 6-10 units per hour, until the fingerstick glucose measurement falls below 10 mmol/l. You should then titrate the insulin infusion rate against the fingerstick glucose measurement (sliding scale). Measure fingerstick glucose at least hourly until the patient is better. If the glucose level does not fall you should check the insulin infusion pump and increase the infusion rate if necessary.Insulin replacement shifts potassium into cells and can cause potentially lethal hypokalaemia. You should therefore take a potassium measurement from the arterial blood sample. Occasionally the potassium may be already low at presentation (below 3.5 mmol/l). In this case you should withhold insulin until replacement of potassium is underway.

Potassium replacement

For most patients once you have started the initial fluid and insulin you should give potassium in the intravenous fluid. For a potassium level of:Less than 3.5 mmol/l add 40 mmol potassium per litre infused

3.5-4.9 mmol/l add 20 mmol potassium per litre infused

5.0 mmol/l and above do not add potassium.

You should check the serum potassium urgently two hours after starting treatment with fluid and insulin and aim for a target of 4-5 mmol/l. After a further two hours you should take another potassium measurement and adapt the infusion rate again.

General measures

management of any underlying illness. You should nurse the patient in a high care area. Antibiotic treatment is recommended only if there is evidence of bacterial infection. Hypotensive patients need urinary catheterisation. You should consider nasogastric drainage and appropriate airway management for drowsy or comatose patients because of the risk of gastric dilatation and aspiration pneumonia.You should continue to monitor levels of glucose, electrolytes, and bicarbonate and urine output. Watch out for occult infection, gastroparesis, and cerebral oedema.

Most patients should improve within 24-48 hours with this management. Once the patient is feeling better, is able to eat and drink, and has a blood glucose of 4-10 mmol/l you can start regular subcutaneous insulin with a meal. You should stop the intravenous infusion 30 minutes later. If the patient is not improving clinically despite metabolic improvement then carefully reassess to identify other additional pathologies.

Complications of diabetic ketoacidosis

Cerebral oedemaCerebral oedema is a worrying complication of treatment. It usually occurs only in children and young adults. The cause is unclear but is probably related to shifts in serum and cerebral osmolality. Retrospective studies have implicated treatment with bicarbonate, giving too much or too little intravenous fluid, and treatment with insulin as potential contributors.

You should suspect cerebral oedema in young people with diabetic ketoacidosis whose conscious level falls as metabolic parameters improve. If you do suspect cerebral oedema you should seek help from a senior clinician. Start mannitol immediately and reduce the fluid infusion rate before carrying out a CT brain scan to look for other causes of reduced consciousness. If you withhold treatment until you find radiological evidence of cerebral oedema the patient will probably die.

Hypophosphataemia

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis lose large amounts of phosphate in their urine. This rarely causes problems. You should consider phosphate infusion in patients with respiratory muscle weakness, haemolysis, or hypotension with severe hypophosphataemia (below 0.35 mmol/l). Routine supplementation does not improve outcome and may precipitate hypocalcaemia.Respiratory failure

Respiratory failure may be caused by the precipitating illness. Adult respiratory distress syndrome rarely occurs and should be treated by intermittent positive pressure ventilation and meticulous fluid balance.Difficulties and controversies in the management of diabetic ketoacidosis

BicarbonateThe role of bicarbonate in diabetic ketoacidosis is debated. Most agree that it is rarely indicated. Even patients with profound acidosis (pH less than 6.9) due to diabetic ketoacidosis should improve with insulin and fluid.

There are theoretical concerns that bicarbonate therapy may increase the risk of cerebral oedema and accelerated ketogenesis. In the setting of severe acidosis and cardiovascular collapse bicarbonate therapy is justifiable. If you decide to give bicarbonate you should use 500 ml of isotonic sodium bicarbonate (1.26%) with frequent monitoring of the pH.

Anticoagulation

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis are ill and dehydrated. There is no evidence that the mortality of diabetic ketoacidosis is due to an excess of venous thromboembolism. Standard practice is to give prophylactic low dose subcutaneous heparin when patients are immobile.Prognosis of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis

The prognosis of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis is generally good. Mortality is about 5% and is mostly due to a severe precipitating illness.Good management should minimise mortality. Most patients should improve within 24-48 hours with good management. You should not discharge your patient at this stage but you should talk to them about preventing further episodes.

Preventing further episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis

In many patients a minor illness such as gastroenteritis causes diabetic ketoacidosis because they do not follow the "sick day rules." These are instructions (preferably written) that patients with diabetes should follow when they feel unwell, particularly if they vomit. Sick day rules include advice to monitor blood glucose, increase insulin dose accordingly, and take sufficient fluid.Poor injection technique, faulty injection devices, pump failure, and inappropriate high calorie drinks may also contribute to the development of diabetic ketoacidosis. Make sure your patients understand this.

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

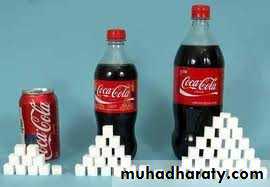

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma usually occurs in older patients with (often previously undiagnosed) type 2 diabetes. It is less common than diabetic ketoacidosis. There are recent reports of children presenting with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state. Risk factors include obesity, African American race, and excessive consumption of high calorie fluids.Causes, definition, and diagnosis

We do not completely understand the pathogenesis of hyperosmolar non-ketotic state. Insulin deficiency is sufficient to cause a strong hyperglycaemia and a profound osmotic diuresis. Ketogenesis is minimal, presumably because the remaining insulin inhibits lipolysis.Hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is therefore defined as:

Hyperglycaemia (at least 30 mmol/l)Hyperosmolality (at least 340 mosmol/kg)

Absence of acidosis (bicarbonate greater than 15 mmol/l)

without strong ketonaemia (urine ketones less than ++ on test stick measurement).

Use the following formula to calculate osmolality:

2 x (sodium + potassium) + urea + glucose.Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar non-ketotic state may overlap. For audit we recommend that you classify hyperosmolar hyperglycaemia with ketoacidosis as diabetic ketoacidosis.

The onset of hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is insidious and patients are often critically ill at presentation. If the patient is too drowsy to provide a history, relatives or carers may report thirst, polyuria, and progressive obtundation. A precipitating illness may be obvious and can distract you from the metabolic crisis, especially if the patient is not known to have diabetes. It is important, therefore, that you routinely measure blood glucose and electrolytes in all sick, drowsy patients who present to hospital. Once these results are available, the diagnosis becomes obvious.

It is important, therefore, that you routinely measure blood glucose and electrolytes in all sick, drowsy patients who present to hospital.

Managing patients with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

Hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is dangerous and warrants high dependency care. As for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis you should look for and treat precipitating illnesses such as bacterial infection or myocardial ischaemia. Stop drugs that contribute to hyperosmolar non-ketotic state if possible but maintain or even increase glucocorticoids to prevent the possibility of adrenal crisis. Multiorgan failure may occur and needs appropriate intensive care.Guidance for managing hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is similar to that for diabetic ketoacidosis and should be available in your hospital. Important general principles of management are:

• Replace fluids

• Correct insulin deficiency

• Give antibiotics

• Give anticoagulants.

Fluid replacement

Patients with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state are severely dehydrated. It is important not to correct dehydration too aggressively, particularly in frail patients. Serum sodium is often highly elevated when the patient first arrives (at least 150-160 mmol/l). We recommend 0.9% saline as the initial fluid resuscitation to prevent too rapid correction of osmolality.You should monitor sodium and potassium levels frequently. If sodium levels rise progressively, consider switching the intravenous fluid to 0.45% saline or even 5% dextrose. Although your patient will need large volumes of fluid, you can give these over 48-72 hours.

Recovery from hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is often slow, sometimes taking several days to weeks.

Insulin replacement

Patients are often sensitive to insulin and glucose levels fall rapidly. You should titrate the insulin infusion as for diabetic ketoacidosis. Convert patients who recover to subcutaneous insulin with the advice of the specialist diabetes team. Some patients may eventually manage with diet or oral hypoglycaemic agents.Antibiotics

Adults with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state usually have an important precipitating illness, typically bronchopneumonia. If no illness is evident at the time of admission consider broad spectrum antibiotics after you have taken cultures. Bronchopneumonia often becomes obvious as rehydration occurs.Anticoagulation

Thromboembolic disease is a common complication and our practice is to give preventive subcutaneous heparin routinely.

Complications of hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

Focal seizures are common when treating hyperosmolar non-ketotic state. These usually settle as the patient improves.

Prognosis of patients with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state

Mortality with hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is 15%, which is higher than with diabetic ketoacidosis. Age is the strongest predictor of death. Recovery from hyperosmolar non-ketotic state is usually slow and is likely to take several days.

Cerebral oedema

Cerebral oedema is a complication of diabetic ketoacidosis and is not a recognised complication of non-ketotic hyperosmolar state.Deterioration in consciousness in a young patient with diabetic ketoacidosis whose metabolic parameters are improving suggests cerebral oedema. You should treat this immediately (give mannitol and reduce the fluid infusion rate) without waiting for radiological evidence of cerebral oedema.