Dermatological emergencies

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Learning outcomes

By the end of this module, you should be able to:Describe the clinical features of three skin conditions which

most commonly cause dermatological emergencies:

• Erythroderma

• Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

• Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

List the common causes, and some of the rarer causes, of these conditions

Explain, in outline, the pathology of these conditions

Explain how to investigate and manage these conditions.

About the authors

Ausama A Atwan is a clinical lecturer in the department of dermatology at Cardiff University. He has interests in paediatric dermatology and psoriasis.

Maria L Gonzalez is a senior clinical lecturer and director of postgraduate dermatology courses in the department of dermatology at Cardiff University.

Why we wrote this module

We wrote this module to help you to recognise patients with rare, but important, dermatological emergencies. Estimates of the incidence of acute dermatoses vary widely; it has been reported to be from 1 to 70 per 100 000 people attending dermatological outpatient clinics.1 2 However, if you miss the diagnosis this can delay treatment, leading to scarring and even avoidable deaths.

You should aim to recognise patients with these conditions and start treatment early. This module covers the more common skin conditions that can present acutely:

Erythroderma

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Key points

The main cause of erythroderma is an exacerbation of a pre-existing skin diseaseYou should keep patients with idiopathic erythroderma under observation as cutaneous T cell lymphoma may develop years after diagnosis

Sulfonamides are the most common drugs which cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

If you see an unwell child with tender skin, think of the diagnosis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Erythroderma

In this condition, patients present with red and inflamed skin that covers most of their body surface area, along with various degrees of scaling. It is also known as exfoliative dermatitis, dermatitis exfoliativa, and “red man syndrome.”Figure 1: A patient with generalised erythema and extensive scaling on the legs. The same features were present on the patient's trunk (more than 90% of the body surface area was involved).

Causes

There is no identified cause in about 10% to 30% of patientsIn about 60% of patients, erythroderma is an exacerbation of a pre-existing skin condition

In the other 40% of patients with previously normal skin, the causes include:

Drug reactions

Carbamazepine

Cimetidine

Malignant lymphomas

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides

Sézary syndrome

Rarer causes include:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris

Seborrhoeic and contact dermatitis

Pemphigus foliaceus

Norwegian scabies

Netherton syndrome (in neonates).

Clinical presentation

The onset of erythroderma is usually insidious, except where it is drug induced, when it is usually abrupt and florid. The typical age of affected patients is between 40 and 60 years,and men are affected more than women, with a male to female ratio of about 3 to 1.As well as the diffuse, scaly erythema that covers at least 90% of the body surface area, patients usually have other symptoms, including:

• Itching

• Malaise

• Fatigue

• Fever

• Oedema.

If a pre-existing skin disease exists, you should enquire about previous treatment. For example, psoriatic erythroderma may develop in a patient with psoriasis as a result of phototoxicity or a sudden withdrawal of topical or systemic steroids

The nature of the signs and symptoms may provide valuable clues to the underlying cause of erythroderma. For example:

Islands of uninvolved skin within the erythematous areas suggest mycosis fungoides

Salmon or orange-red coloured erythema suggests pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Generalised lymphadenopathy is a common finding in patients with erythroderma. However, when the lymph nodes exhibit lymphomatous characteristics, such as large size and rubbery consistency, and the cause of the erythroderma is undetermined, you should consider lymphoproliferative disease or Sézary syndrome.

Complications

Patients with erythroderma may develop complications, which you can anticipate by thinking about the underlying pathology of the condition. You should use supportive treatment to minimise the impact of these complications.In particular, you should look out for:

Hypothermia - due to vasodilatation

High output cardiac failure - due to increased blood flow and leaky capillaries

Hypoalbuminaemia - due to desquamation of skin and exudation

Sepsis - due to impaired skin barrier function.

Investigations

In patients who have no history of dermatological disease or new medications, it can be difficult to find the underlying cause of erythroderma. Blood tests are usually unhelpful, and so you should consider taking skin and lymph node biopsies.If you suspect that the cause may be an internal malignancy, you should investigate according to your clinical suspicion.

Diagnostic approach in a patient with erythroderma

Take a history looking for precipitating causes. You should particularly ask about:Pre-existing skin diseases

Recently introduced medications

Systemic illnesses which would suggest malignancy, such as:

Unexplained lethargy

Haemoptysis

Unexplained weight loss

Painless lymphadenopathy

A previous history of erythroderma

Examine the patient, paying particular attention to:

Heart rate, blood pressure, and peripheral perfusion - the patient may be in shock

The skin on their whole body - ask the patient to undress fully to look for any signs which suggest a cause

Nails - to look for signs of psoriasis

Oral mucosa - to look for signs of immunobullous disease

Lymph nodes - to look for signs of malignancy

Organomegaly - to look for signs of lymphoma

Arrange appropriate investigations:

Full blood count (including Sézary cells count if you suspect Sézary syndrome)Urea and electrolytes - to assess the level of dehydration

Multiple skin biopsies* - for histology and to arrange testing for:

Direct immunofluorescence - to look for immunobullous diseases

Gene rearrangements - to consider the presence of lymphomas

Antinuclear antibody test - to look for systemic autoimmune diseases

If you suspect lymphoma or an internal malignancy, depending on the probable diagnosis, you may arrange:

A chest x ray - for lymphoma or lung cancer

Computerised tomography - for solid tumours

Immunoelectrophoresis - where lymphoproliferative disorders are included in the differential diagnosis

A bone marrow examination - for leukaemias

A lymph node biopsy - to diagnose lymphoma or metastasis.

*You should take multiple samples (usually two or three) because nonspecific inflammatory changes obscure diagnostic features in about one third of biopsies.

Management of erythroderma

Because of the risk of complications, you should admit most patients with erythroderma to hospital, ideally to a dermatology ward, but otherwise to a general medical ward. Once there, you must stabilise the patient’s condition, investigate for triggering factors, and treat any underlying cause.

Initial approach to the management of erythroderma

Admit the patient to a warm humid environment by:Applying a greasy emollient such as 50:50 white soft paraffin and liquid paraffin hourly. Consider using a tubular bandage body suit

Ensuring the room is kept warm to prevent hypothermia and also to reduce skin irritation, which could lead to pruritus

Replace lost fluids and electrolytes

Apply bland emollients and low potency topical steroids

Cover weeping and crusted sites with non-adherent dressing

Elevate patients’ legs to decrease peripheral oedema

Prescribe sedating antihistamines to relieve itching and anxiety

If secondary infections develop, treat with systemic antibiotics

Most patients do not need analgesia

In most patients you should avoid using potent topical steroids or tacrolimus, due to the risk of systemic absorption. However, there are specific conditions where a short course of systemic steroids is useful.

It is important to look for underlying causes, because this may allow you to target your treatment:

In erythroderma caused by a drug reaction you should withdraw the causative drug and, if necessary, replace it. You should also prescribe a short course of systemic corticosteroids

In patients with psoriatic erythroderma corticosteroids are contraindicated. You should use ciclosporin or methotrexate, or even biological agents such as infliximab infusion

With patients in whom you diagnose or suspect cutaneous T cell lymphoma you must avoid systemic immunosuppressive agents such as ciclosporin, as these patients are often immunosuppressed and so are prone to infection.

Clinical tip: erythroderma and malignancy

Consider malignancy in patients with erythroderma without an obvious cause. An underlying malignancy can cause erythroderma, but remember also that the patient may go on to develop cutaneous T cell lymphoma years after their diagnosis. For this reason, these patients should be followed up by a specialist for the long term.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

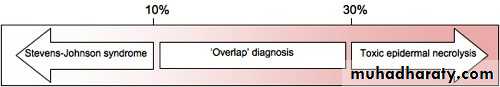

Are drug induced or idiopathic reactions of the skin and mucous membranes. It is crucial that you recognise them early because delayed diagnosis can lead to pain, scarring, and even death.There is no consensus about the relationship between these diseases in the literature. For simplicity, we will adopt the widely held view that Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (also known as Lyell syndrome) are different severities of the same disease. The main difference between them is the amount of body surface area involved.

Patients with less than 10% of their body surface area involved have Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Patients with more than 30% body surface involvement have toxic epidermal necrolysis

Patients with between 10% and 30% of their body surface involved are said to have an overlapping diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

• Figure 2: Classification by percentage of body surface area involved

• Learning bite: estimating body surface area• There are a number of simple methods that have been developed for the treatment of patients with burns, which can be used to estimate the surface area affected by a skin disease. These methods need to be adapted if they are used in children.

• Wallace’s rule of nines - individual body parts have been defined, which each represent about 9% of the body surface area, such as the front of the chest. By counting the number of body parts, you can estimate the total body surface area affected

• Lund and Browder chart for burns - this is a diagram showing the approximate body surface area affected represented by parts of the body

• Hand method - using the patient’s own hand, you can count the number of times the area of the palm can be used to cover the affected skin. The palm covers about 1% of the body surface area

The palm covers about 1% of the body surface area

Figure 3: Mucocutaneous lesions in Stevens-Johnson syndrome

• Figure 4: Extensive skin desquamation in toxic epidermal necrolysis.Epidemiology

Estimates range from 1.1 to 7.1 patients per million per year in the case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a typical age of onset between about 25 and 50 years. Interestingly, the incidence of toxic epidermal necrolysis in patients infected with HIV is higher than in the general population.Mortality

The mortality rate varies between 1% and 5% in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and can be up to 30% to 50% in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Causes

It is thought that both of these disorders are hypersensitivity reactions mediated through immune complexes, although the mechanism is not fully understood. Sulfonamides are the most well known drugs that cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Sulfonamide antibiotics are now rarely used alone, but drugs in the sulfonamide family include co-trimoxazole, thiazides, and sumatriptan. It is thought that there is a lower risk of skin reactions with the non-antibiotic sulfonamides.Typically, the features of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis appear within three weeks of starting new medications used on a short term basis, and in the first two months after starting a new long term drug.

Table 1: Drugs implicated in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Drugs usually used on a short term basisDrugs usually used on a long term basis

Sulfonamides

Co-trimoxazole

Thiazides

Sumatriptan

Antiepileptics

Phenobarbital

Phenytoin

Carbamazepine

Valproic acid

Oxcarbazepine

Antibiotics

Ampicillin

Amoxicillin

Quinolones (ciprofloxacin)

Cephalosporins

Oxicam non-steroidal

Tenoxicam

Piroxicam

Chlormezanone (a rarely used anxiolytic)

Allopurinol

-

Corticosteroids

Some authors suggest that, unlike erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome is not caused by infections. However, infectious agents such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Yersinia species have been linked to Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

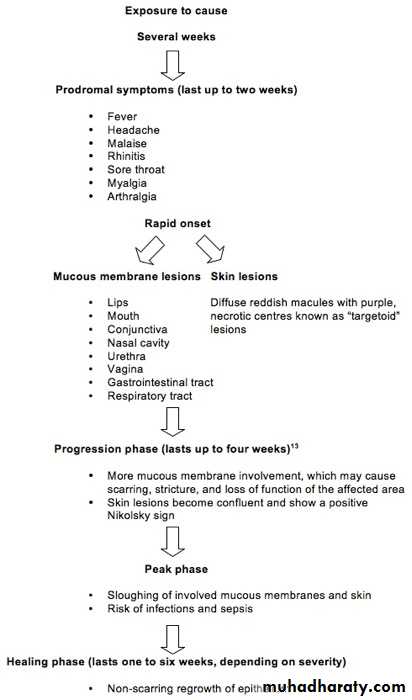

• Clinical presentation

• Symptoms and signs in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis typically progress through a series of phases.• Figure 5: Phases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Learning bite: Nikolsky sign

The Nikolsky sign is positive when gentle sideways pressure applied to the skin causes the upper layer to separate. In order to avoid causing the patient any more skin damage or discomfort, you should be very cautious about using this test.The skin lesions in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are sometimes described as “targetoid” because they look similar to the classical target lesions seen in erythema multiforme. But instead of the three zones of colour seen in target lesions, targetoid lesions have two zones of colour; a vesicular, purpuric, or necrotic centre and a surrounding macular erythema.

Complications

You should look out for and treat acute complications, such as:Hypothermia - due to vasodilatation

High output cardiac failure - due to increased blood flow and leaky capillaries

Hypoalbuminaemia - due to desquamation of skin and exudation

Sepsis - due to impaired skin barrier function

Airways obstruction - due to mucosal lesions in the oropharynx and tracheobronchial tree.

Chronic complications occur if lesions heal with scarring, which may cause:

Strictures

Loss of function, especially around the mouth

Disfigurement.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis will normally be made on the clinical findings. You should consider other conditions that have a similar appearance, such as:

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome

Erythema multiforme

Autoimmune blistering disorders, like pemphigus

Burns.

In cases where it is difficult to reach a diagnosis, consider taking skin biopsies from the patient for histological examination.

Management

It is essential that you aim to recognise the condition early and adopt a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to address patients’ systemic responses to the condition. This should include:Specialist nursing care to ensure adequate skin care

Review by an ophthalmologist of all patients

Selected patients should also be seen by a respiratory medicine specialist and gastroenterologist if you suspect that these organs are involved

A nutritionist may help, especially if the patient has difficulty eating due to oral lesions

Psychological support should be provided as needed, especially when disfigurement or scarring occurs.

Learning bite: the SCORTEN classification

A scoring system to assess the severity of toxic epidermal necrolysis, called SCORTEN, is a practical tool that can reflect the prognosis of the condition. SCORTEN should be calculated within the first 24 hours of admission and it includes the following variables:Age older than 40 years

Presence of malignancy

Heart rate greater than 120 beats/min

Initial percentage of skin detachment greater than 10% of body surface area

Blood urea nitrogen greater than 10 mmol/l (27 mg/dl)

Serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/l (252 mg/dl)

Bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/l.

Table 2: SCORTEN scoring system

SCORTEN

Mortality rate (95% CI)0-1

3% (0.1-16.7)

2

12% (5.4-22.5)

3

35% (19.8-53.5)

4

58% (36.6-77.9)

5 or higher

90% (55.5-99.8)

• According to the SCORTEN scoring system, each feature is assigned one point and the total number is SCORTEN. The mortality based on the SCORTEN number is as follows:

Most of the evidence regarding the use of disease specific treatments is unfortunately based on uncontrolled studies with small sample sizes, because these conditions are rare. However, there are two important steps that you can take to reduce mortality and length of hospital stay:

Withdraw the drug(s) which caused the reaction immediately

Refer the patient promptly to a specialised unit. This will vary depending on the severity of the patient’s condition, but may include a burns or intensive care unit for some patients.

Management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Supportive measuresAdmit the patient to hospital. For patients with extensive skin involvement, you should admit them to a burns unit or an intensive care unit

Immediately withdraw any possible causative drug

Monitor the patient’s airways and, if compromised, intubate

Manage the patient on an airflow or foam mattress

Replace fluid and electrolytes*

Monitor urine output*

Provide nutritional support, especially protein

Prescribe pain relief†

Apply sterile wound dressings‡

Involve colleagues from other specialties early, such as:

Ophthalmology

Respiratory medicine

Gastroenterology

Treat infections as required (it is not generally recommended that you use prophylactic antibiotics).

The amount of fluids that you will need to replace is less than that required in patients with burns of a similar body surface area. Generally, you should aim to administer sufficient fluids to maintain a urine output of 50 to 100 ml/hour in adults and around 1 ml/kg/hour in children.

†Patients may have pain around the lips and mouth that can be managed using viscous lidocaine on the oral mucosa, and diphenhydramine or sodium bicarbonate mouthwashes.

There is disagreement in the literature on whether to debride wounds or treat them conservatively. You should cover skin erosions with emollients, and add in topical antibiotics if there are signs of infection, but avoid topical silver sulfadiazine because of its sulfonamide base. Use hydrocolloid dressings, gauze, or skin grafting to cover the exposed dermis.

Disease specific treatments include:

• Systemic corticosteroids

• Intravenous immunoglobulins

• Cyclophosphamide

• Ciclosporin

• Plasmapheresis.

Plasmapheresis.

The efficacy of these agents has not been demonstrated by randomised controlled trials, and the available data that supports their benefits are based on case reports and anecdotal data.The use of systemic steroids and other immunosuppressive agents is still debatable because of the risk of infection. Giving intravenous immunoglobulins early seems to improve survival and reduce long term morbidity due to complications in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a disorder that is usually seen in infants and young children, and rarely in adults. It is caused by circulating exotoxins secreted from particular strains of Staphylococcus aureus. These toxins cause skin desquamation and separation beneath the horny layer of the epidermis, which leads to the formation of flaccid bullae.

Causes

This syndrome occurs in people infected or colonised with strains of S aureus that secrete exfoliative exotoxin. Phage group II S aureus is the most commonly isolated strain, but S aureus groups I and III may also infrequently cause staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Overall, only about5% of all S aureus strains produce these toxins.

Two exfoliative exotoxins have been identified so far: A and B. Exfoliative toxin A is the more commonly secreted. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and bullous impetigo are caused by the same exotoxins. In bullous impetigo the toxins act locally at the infection site, targeting desmoglein-1, a component of the intraepidermal desmosome structure. But in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome the exfoliative toxin is found in the circulation, and so the skin blisters and desquamation are more generalised.

Clinical presentation

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome usually affects children under the age of 5 years, probably because they lack antibodies against exfoliative toxins A and B. It has been shown that antibodies to these toxins are found in only 30% of children aged 3 to 24 months, compared to 91% of adults over 40 years. There have been some case reports of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in adults. Adults with compromised immune systems are at higher risk.After a short period of prodromal symptoms, tender and reddened areas appear on the skin. This is followed by the formation of bullae, which can be extensive. As the toxins cause tissue separation quite superficially, the resulting blisters are flaccid and rupture easily. This results in reddened, raw looking blister bases, which resemble scalded skin.

Table 3: Clinical presentation of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome11

Prodromal symptoms:Sore throat

Conjunctivitis.

Within 48 hours:

Fever

Malaise

Tender reddened patches on the:

• Face

• Neck

• Axillae

• Perineum.

Flaccid bullae develop within the reddened areas.

The Nikolsky sign is positive.

Bullae rupture easily and reveal a moist reddened base (scalded appearance).

Skin lesions often heal over seven to 10 days without scarring

• Figure 6: An unwell child with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome affecting his face and neck

• Figure 7: The blisters are flaccid and rupture easily to reveal tender erythematous skin with a "scalded" appearance.

•

Patients tend to get staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome only once, although recurrent episodes have been reported.

Complications

Hypothermia - due to vasodilatation

Sepsis - due to impaired skin barrier function.

Diagnosis

You would usually make the diagnosis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome on clinical grounds. Tender skin is a key diagnostic feature.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome can appear similar at presentation. The following table highlights the differences between the two disorders.

Table 4: Comparison between toxic epidermal necrolysis and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

-

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Age

Usually adults

Usually under 5 years

History

Prior drug ingestion

Not related to drugs

Mucous membranes involved?

Yes

No

Nikolsky sign

Positive on affected skin

Positive even in unaffected skin

Histology

Full thickness epidermal necrosis

Intraepidermal split through the stratum granulosum

Clinical tip

If you see an unwell child with conjunctivitis and tender, blistering skin, you should consider a diagnosis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Investigations

In cases where it is difficult to make a diagnosis, you should take biopsies for25:

Histology

Microbiology.

Histology will show intraepidermal cleavage through the granular layer. Immunofluorescence studies can rule out other blistering skin conditions.

It is also useful to isolate the bacteria producing the exotoxin by microbiological studies. Since the effects are produced by circulating exotoxins, skin blisters are usually culture negative. You should take samples from probable infection sites, which are commonly the oral or nasal cavities, the throat, or the umbilicus. Samples can be examined by Gram staining, as well as cultured to confirm the presence of toxin secreting staphylococci and to determine antibiotic sensitivities. The polymerase chain reaction on serum samples can also show the presence of the toxin.

Management

It is crucial that you recognise this condition early and treat it with parenteral antistaphylococcal antibiotics, such as flucloxacillin. If treated promptly, the condition resolves quickly (within days) and the skin lesions heal without scarring.As the disease process only affects the epidermis, the haemodynamic, fluid, and electrolyte imbalance are not as severe as in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. However, when the skin involvement in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome covers several body sites, such as the face, trunk, or limbs, and the patient is persistently unwell, you will need to arrange for more intensive care. This should include:

Regular monitoring of core body temperature

Monitoring of fluid and electrolytes

Aseptic wound care

Assessment and management of pain.

Management of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Admit the patient to hospitalMonitor the patient’s temperature, which may be disturbed by:

Underlying infection

Inflammatory response

Peripheral vasodilatation

Replace fluid and electrolytes*

Monitor urine output

Provide nutritional support

Prescribe pain relief

Leave blisters intact

Apply sterile wound dressings to eroded skin.

Disease specific treatment

You should do the following:

Prescribe parenteral antibiotics (flucloxacillin)

Avoid corticosteroids because of the potential to exacerbate the condition.

*This can be achieved either orally or parenterally, depending on the severity of the patient’s condition and their hydration status. You would typically start rehydration with a bolus of 20 ml/kg of Ringer’s lactate solution. You should repeat this, as clinically indicated, followed by maintenance therapy. Generally, you should manage fluid losses on the basis of exfoliation of skin being similar to that seen in a burn patient.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Reports suggest that early administration of intravenous immunoglobulins in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis may improve survival and reduce morbidity.Your answer

Correct answera.

Toxic shock syndrome toxin

b.

Alpha-toxin

c.

Exfoliative toxins

d.

Enterotoxins

• Which of the following S aureus toxins causes blister formation in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome?

•

a : Toxic shock syndrome toxin

As the term implies, this toxin results in toxic shock and the patient presents with septic shock, which can rapidly progress to stupor, coma, and multiorgan failure. The characteristic rash often seen early in the course of the illness resembles sunburn and can involve any region of the body, including the lips, mouth, eyes, palms, and soles. The rash peels off within two weeks in those who survive the infection.b : Alpha-toxin

Alpha-toxin has various effects on endothelial and blood cells in laboratory studies. It lyses red blood cells, induces inflammatory and vasodilatory mediators, and promotes cell death by apoptosis. However, it is not known to what extent it contributes to clinical disease.27

c : Exfoliative toxins

Exfoliative toxin A and, less commonly, B target desmoglein-1 (a protein that maintains adhesion between epidermal cells) and, therefore, cause a loss of cell adhesion in the epidermis, which results in blisters and skin sloughing.

d : Enterotoxins

These toxins cause gastroenteritis