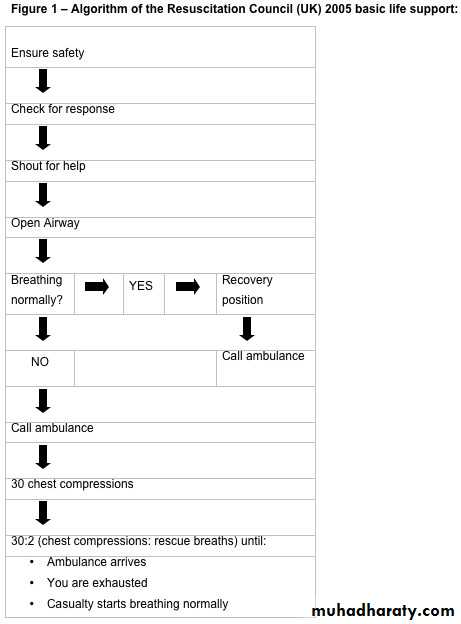

• Basic life support

Basic life supportد. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Learning outcomes

After completing this module, you should be:Able to explain the importance of basic life support.

Able to describe the UK Resuscitation Council basic life support guidelines 2005

More able to perform basic life support in an emergency situation.

About the authors

Charlotte Davies is a CT1 trainee in emergency medicine at St James's University Hospital, Leeds as well as county clinical officer for students at St John Ambulance, South and West Yorkshire.Mike Harris is senior resuscitation officer at Airedale General Hospital and assistant clinical director of St John Ambulance, South and West Yorkshire.

Why we wrote this module

"We have written this module so that doctors can keep up to date with current guidelines on basic life support (the UK Resuscitation Council 2005 guidelines).

"Doctors at all levels are expected by the public and their profession to be able to handle a medical emergency, within the limits of their competence. The General Medical Council makes this a professional obligation in Good Medical Practice (Treatment in emergencies - paragraph 11).

"While you may be able to do this in the familiar setting of a hospital or clinic, with a team around you and lots of equipment, it may be more difficult to remember the essentials of basic life support out in the "real" world."

Key points

Checking for danger is vital - always put safety first. If in doubt, step back and call for helpBefore phoning for an ambulance, open the casualty’s airway with the "head tilt/chin lift" manoeuvre

Give cycles of 30 chest compressions to two rescue breaths until the ambulance arrives

Do not delay chest compressions in an attempt to clear the airway.

Clinical tips

If you cannot remember anything else in an emergency, check for danger and perform a head tilt/chin liftIf an unconscious casualty with an open airway is not breathing normally, assume that they need resuscitation. Agonal gasps are commonly misinterpreted as breathing.Try to avoid any interruptions in chest compressions - this has been shown to reduce survival

Introduction

A casualty in a state of cardiac arrest is at risk of irreversible damage to their brain and heart if perfusion is not re-established within three to four minutes. The chance of a casualty surviving has been shown to reduce by around 10% with each minute that the start of resuscitation is delayed. And it is known that attempts to resuscitate a casualty more than 10 minutes after they have collapsed are unlikely to succeed.The "chain of survival" is a term used to describe the important links that must be in place for improved outcome from cardiac arrest. If all the links are in place, the probability of survival is increased.

Link one - early access

The earlier help can get to a patient, whether it is from a paramedic or a lay first aider, the sooner the other links can be put in place.

Link two - basic life support

Basic life support is important because it allows anyone to maintain a supply of oxygenated blood to the vital organs of a person in cardiac arrest, without specialist equipment. This can keep the brain perfused until an ambulance crew arrive and start advanced life support, especially defibrillation. Early initiation of basic life support is the second link in the chain of survival and should be started as soon as possible.

Link three - defibrillation

Basic life support has also shown to increase the amount of time that the patient stays in ventricular fibrillation before going into asystole, which is usually untreatable. Patients who receive early basic life support before defibrillation are more likely to regain a spontaneous output. It is thought that this is because such patients remain in ventricular fibrillation for longer than those who do not receive basic life support before defibrillation.• Link four - advanced life support

• Advanced life support must be initiated as soon as possible. Delayed basic life support and delayed advanced life support are associated with a poor outcome, and have been called “the failure zone” by some researchers.• If all the links in the chain are complete - early access, early basic life support, and rapid defibrillation, combined with early advanced care - long term survival rates following cardiac arrest can be as high as 30%.

• In this module we will go through a typical resuscitation scenario that could happen out of hospital. At each point, try to answer the question posed before reading the section which follows it.

1. You are walking along the pavement on your way to work and see a man laid motionless in the middle of the road. What should you do first?

Talk to the man

Go and assess for breathing

Look around for traffic

Phone for an ambulance

Common hazards include:

Road traffic accidentsIf you are the first person to arrive at a road traffic collision you should think about using your own vehicle to protect the scene. But ensure that your vehicle does not cause an unhelpful obstruction, which could aggravate the situation or block access to the emergency services. If other vehicles are involved in the collision, get someone to turn off their ignitions to reduce the fire hazard and put their handbrakes on.

You should ensure that you can be easily seen by approaching traffic. If you are trained in resuscitation and think you might stop at an accident, it is worth keeping a high visibility vest in your car. Alternatively, if you have a white coat with you, put it on.

Buildings

You should never enter a building which is on fire, and should always consider whether you are the most appropriate person to enter the site. If in doubt, it is better to call for help and wait for the emergency services to arrive. If there has been an incident such as an explosion, which may have damaged the structure of a building, you need to look out for evidence of structural damage. It is important to look up for things that could fall on you, and to look down for places where you might fall.

Infection

The risk of a rescuer contracting an infection from a casualty during resuscitation is very low. There have been no verified reports of a person catching HIV or hepatitis as a result of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but there are isolated case reports of rescuers being infected with tuberculosis.Herpes simplex can be transmitted via rescue breaths and there are isolated case reports of clinicians catching herpes infections.

In 1998, only 15 documented episodes of infections transmitted by mouth to mouth resuscitation had been reported. Most of these were bacterial infection, and there were no reports of hepatitis being transmitted. A PubMed search, conducted in July 2009, using the MESH terms "cardiopulmonary resuscitation" and "infection" did not find any more recent case reports.

If you wish to minimise the risk, or just for your personal comfort, keep a pair of gloves and a pocket mask or face shield in your car or bag. There have been no human studies to assess how effective these devices are, but laboratory studies have shown that some filters, or devices with one way valves, prevent transmission of oral bacteria from the casualty to the rescuer.

People

The casualtyIf the casualty is semiconscious, they may be uncooperative or even hostile to you.

Bystanders

If you are responding to an incident in a public place you should be aware of how other people may respond to you. If you are helping the victim of an assault, remember that their attacker may return. When bystanders are drunk, drugged, or highly emotional, there is a danger that your attempts to help might be misinterpreted, particularly if you are a man and the casualty is a woman.

• Announcing that you are a medical professional can help to gain people's cooperation and respect. If you have your work identity badge with you, wearing it can give you more authority.

• Recruiting a bystander to help and giving a running commentary can help to clarify what you are doing and why. For example: "She's unconscious, I'm going to roll her into the recovery position so she can breathe more easily . . ."

2. You have ensured that the scene is safe. You are in a quiet side road with little traffic, and there is no debris on the road. What should you do next?

Check for an open airway

Shout for help

Ask the man if he can hear you, while gently tapping his shoulders

Stand on the pavement and shout to the man

Ask the man if he can hear you, while gently tapping his shoulders

Before calling out the emergency services, you need to quickly check that there actually is a medical emergency to deal with. There could be several non-medical reasons for this situation, for example:

The man might be drunk, but otherwise well

The man might be looking under his car.

Once you have checked that everyone is safe, you need to see if the casualty will respond to you. The simplest and most reliable way to do this is to call loudly. You should touch him on the shoulder (in case he is deaf). You should give a direct command, like "Open your eyes!" - it is harder to ignore a direct command.

If there is no response to your voice, he may still respond to pain. The following techniques cause pain without causing serious harm:

• Pressing a knuckle into the sternum

• Pinching an earlobe

• Squeezing a nail bed.

Always check for voice and pain responses separately; otherwise you will not know which stimulus the casualty has responded to.

If you are familiar with the Glasgow coma scale you can use it to grade the casualty's response, but a simpler method is the

AVPU scale.

• AVPU assessment scale

• A Alert• V Responds to voice

• P Responds to pain

• U Unconscious

• In the AVPU system, an A score is equivalent to a score of 15/15 on the Glasgow coma scale, and a U score is equivalent to 3/15.

3. The man lying on the floor does not respond to your voice or to a painful squeeze of his earlobe. What should you do now?

Open the man's airway and give two breaths

Begin chest compressions

Find a phone and call an ambulance

Shout loudly "Help! I need some help here!"

• Shout loudly "Help! I need some help here!"

• Once you know that you are safe and have an unresponsive casualty, you should immediately call for help. You have lots of tasks ahead of you and will need all the help you can get. The most efficient way to do this in the pre-hospital setting is to shout for help.• Whatever the problem turns out to be, you will probably need assistance in the following situations:

• If the casualty is breathing, you will need help to keep the casualty safe while you arrange transfer to hospital

• If the casualty is not breathing, as well as calling for an ambulance, you are likely to need help to perform chest compressions and rescue breathing.

4. In response to your shout for help, a couple of passers by run over and offer assistance. What should you say to them?

"Go and phone for an ambulance"

"I need some help with this man - let me just check if he is breathing"

"Can you keep an eye out for traffic?"

"Have you got a mobile phone on you?"

"I need some help with this man - let me just check if he is breathing"

Your first priority with an unconscious casualty is to ensure they have a patent airway, using the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre. The airway is likely to be obstructed because the lack of muscle tone in an unconscious casualty will cause the tongue and other soft tissues to fall to the back of the throat, blocking the airway. You should assume that the airway is obstructed, until you have opened it.The recommended method for this in the basic life support guidelines is the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre which extends the neck, increasing the size of the oropharynx. The guidelines no longer recommend the jaw thrust technique for lay providers as it is harder to teach, and so is less reliable in a pre-hospital setting. Healthcare professionals should continue to use a jaw thrust. If the jaw thrust fails to provide an adequate airway, they should use a head tilt/chin lift.

Figure 2: Position of your hands when performing head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre

• Figure 3a: Model showing airway obstruction in unconscious casualty• Figure 3b: Model showing effect of head tilt/chin lift on casualty's airway

•

Figure 3a: Model showing airway obstruction in unconscious casualty

Figure 3b: Model showing effect of head tilt/chin lift on casualty's airwayThe head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre is simple to perform, and is an effective way to open the airway:

Place two finger tips under the point of the chin and tilt the head Lift the chin up

Check the airway at regular intervals as it may become obstructed again after you have released the head.

As a lay provider, even if you suspect a cervical spine injury, you should still use the head tilt/chin lift technique, but perform it gently and only as far as necessary to provide a patent airway. Healthcare professionals should use a jaw thrust.

Learning bite

Most preventable deaths, which occur before the emergency services arrive, are due to an obstructed airway .If you cannot remember anything else in an emergency, check for danger and perform a head tilt/chin lift.Learning bite: managing casualties with possible spinal injuries

An unconscious casualty with an obstructed airway is likely to die within minutes unless someone opens their airway. If they have sustained a cervical spine trauma then there is a risk that opening their airway could exacerbate any spinal injury, potentially leading to permanent paralysis. In this situation, you may be faced with a dilemma, and very little time to resolve it.

Both the UK Basic Life Support guidelines and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation recommend that you must open the airway of a casualty who is not breathing normally, even if you suspect a cervical spine injury. It is reasonable to perform manual in line stabilisation of a casualty's spine if you have a skilled assistant available and can do it without delay. But if a patient is not breathing, your overriding priority should be to establish an airway, even if you suspect a spinal injury.

Manual in line stabilisation

Manual in line stabilisation is a method for reducing movement of a casualty's cervical spine. The technique is for an assistant to hold the casualty's head in the midline position by placing their hands firmly on the sides of the head. They should not apply traction to the casualty's neck. A recent systematic review found that it was more reliable than other methods, and recommended that it should be used by emergency department staff.5. After you have opened the casualty's airway, you assess to see whether or not he is breathing. You hear some slow, laboured breathing. What should you do?

Call the ambulance and then start chest compressions

Once the casualty has a patent airway, you should check for the presence of normal breathing. To do this, you should:Look - at the casualty's chest for breath movements

Listen - near their face for breath sounds

Feel - with your cheek for air movements.

Each of the above should be done for a maximum of 10 seconds in total.

Your next action depends upon whether or not the casualty is breathing normally:If normal breathing is present - put the casualty into the recovery position, and then call for an ambulance.If normal breathing is absent - call for an ambulance immediately, and then start chest compressions.

Learning bite: agonal gasps

Agonal gasps are occasional laboured breaths which may be slow or noisy. They are present in 40% of casualties in cardiac arrest. 38 You can think of them as part of the early stages of the dying process. You should take care not to mistake them for normal breathing.If the casualty is making agonal gasps, as in this case, normal breathing is not present.

Recovery position

The recovery position is designed to be a stable position that keeps the airway clear. Any vomit, blood, or other fluids can drain out of the casualty's mouth.

Learning bite: how to put a casualty in the recovery position

Remove the casualty's spectaclesKneel by their side and straighten their legs

Place the arm nearest to you on the floor, at right angles to their body.Bring the arm furthest from you across their chest, and hold onto it.With your other hand, grasp the far leg just above the knee and pull it towards you

Pull on the far leg and the far hand to roll the casualty towards you, onto their side.Adjust the upper leg so that both the hip and knee are bent at right angles

Tilt their head up to provide an open airway

Put the casualty's upper hand under their cheek to stabilise the head.Check their breathing regularly

You should turn the casualty if they have been in the recovery position for 30 minutes.

Figure 4: An unconscious casualty in the recovery position

6. You need to call an ambulance for this unconscious man. What should you say to the emergency operator first?"I need an ambulance. The casualty is not breathing - please come quickly!"

"I'm calling from 0110 222 3333, I need an ambulance to come to 23 Coronary Close, Exeter."

"Hello. Is that the emergency services? I need the police. I think someone's been injured in a hit and run."

"I need an ambulance. The casualty is a man in his 30s who is unconscious and is not breathing. I have opened his airway, and am about to start chest compressions."

"I'm calling from 0110 222 3333, I need an ambulance to come to 23 Coronary Close, Exeter."

You should always give your phone number and location at the start of the conversation. That way, the emergency operator can get help to you even if you are cut off - for example, if the battery runs out in your mobile phone. Do not hang up the phone until the operator tells you to do so.

Dialling for help

You must call for an ambulance immediately if a casualty with an open airway is not breathing normally. If an unconscious casualty is breathing normally, you can call for an ambulance as soon as you have placed them in the recovery position. To call an ambulance, dial:999 (United Kingdom and Ireland)

112 (All EU countries, including United Kingdom)

911 (North America).

The emergency operator will usually ask: "Emergency: which service?" If you have a medical emergency, ask for an ambulance. The ambulance control will call whatever other services are necessary, such as the police.

• Learning bite: METHANE reporting system

• You may find it helpful to use a METHANE report, which is a standard Major Incident Medical Management and Support (MIMMS) format used by paramedics, to provide all the information the ambulance control centre needs.• M Method of contacting

• Provide your telephone number, in case you get cut off.

• E Exact location of incident

• Be as exact as you can. Ask locals for the address. Give numbers - house, junction, or lamppost. If you have a satellite navigation device, give your latitude and longitude.

T Type of incident

Specify what has happened as clearly as you can. For example: "There's been a traffic collision between a car and a petrol tanker . . ."H Hazards (present and potential)

Report anything or anyone that could be a hazard to you, the casualty, or the rescuers. For example: "I can smell petrol near the tanker . . ."

A Access and exit routes

Any local knowledge may be beneficial, particularly for a road accident where traffic may begin to build up.

N Number, severity, and type of casualties

Describe the casualties, giving all relevant details, but be succinct. For example: "The two casualties are men in their late 40s. One is trapped in the driver's seat of the car, and appears to be breathing. The other is lying on the road, and looks like he came through the windscreen. He is not breathing."

E Emergency services present

Tell the operator if there are any trained people on the scene. For example: "I am a pre-registration doctor and there is a trained first aider with me."

7. The man in the road remains unresponsive and shows no signs of breathing. You have called the ambulance, which should be arriving within a few minutes. What should you do while you wait?

Feel for a pulse

Deliver 30 chest compressions

Deliver two mouth to mouth breaths

Conserve your energy and take a rest

Deliver 30 chest compressions

A person with a clear airway who is not breathing is in a state of cardiac arrest. You need to start chest compressions as soon as possible, to propel blood around their brain and heart.Once you know that the casualty is not breathing normally, and that help is on the way, the 2005 basic life support guidelines say that you should immediately start chest compressions. Previous guidelines which recommended starting with mouth to mouth breathing or checking for a pulse have been superseded. This is because of evidence that chest compressions were being delayed unnecessarily.40-42 Chest compressions performed properly can create systolic blood pressures of 60 to 80 mm Hg.43 (The diastolic pressure still remains low during chest compressions.)

Figure 5: Correct position to perform chest compressions

How to perform chest compressionsKneel at the side of the casualty

With both palms facing away from you, interlock your fingers and bend your wrists back

Put the heel of your lower hand in the middle of the casualty's chest

Keep your elbows straight

Using your body weight, push straight down to compress the casualty's ribcage by about one third. In an adult, this is normally 4-5 cm

Gently lift up, but don't lose contact with the casualty's chest

Do this 30 times at a rate of 100 beats a minute

• At their best, chest compressions provide only about 30% of the heart's normal cardiac output. Studies have shown that the efficiency of chest compressions deteriorates within about two minutes, as the rescuers get tired. So, if you have someone to help, you should swap over every two minutes.

8. You begin to deliver 30 chest compressions to the casualty, while your helper, a trained first aider, waits next to you. What should you ask them to do now?

"Take over chest compressions when I get tired"

"Phone the ambulance and give them an update"

"Give two mouth to mouth breaths as soon as I stop"

"Give continuous mouth to mouth breaths while I do chest compressions"

"Give two mouth to mouth breaths as soon as I stop"

The 2005 basic life support guidelines put a much greater emphasis on chest compressions than rescue breaths. So, after performing chest compressions, you should start rescue breaths. If there are two rescuers, one of you should perform cycles of 30 chest compressions while the other gives mouth to mouth (or mouth to nose) rescue breaths between the cycles. Give each breath over about one second and allow three to four seconds for the casualty to breathe out. Giving two rescue breaths should take about 10 seconds.If the casualty's chest does not raise with the rescue breaths, return to another cycle of 30 chest compressions. After these, quickly check the airway visually for obstructions, and reposition their head (head tilt/chin lift) before your next two rescue breaths. Do not delay chest compressions in an attempt to clear the airway.

Some people are reluctant to perform rescue breathing despite the low risk of infection. If you would rather not give mouth to mouth breaths, consider using the mouth to nose technique instead, or ask if someone else will volunteer. If no one is prepared to give rescue breaths, then carry on with chest compressions alone.

Figure 6: Correct position for delivering rescue breaths

Mouth to mouth technique

Make sure the airway is still open

Pinch the casualty's nose

Press your mouth firmly around the casualty's mouth, making a good seal

Blow firmly out, for about one second

Move away from the casualty's mouth for three to four seconds

Look and listen for air movement

Give a total of two rescue breaths before restarting chest compression

Mouth to nose technique

Mouth to nose rescue breaths are an effective technique if there is mouth trauma, if you are unable to get a good seal around the casualty's mouth, or if you are reluctant to give mouth to mouth breaths.Make sure the airway is still open

Hold the casualty's mouth shut

Put your mouth around their nose

Blow firmly out, for about one second

Move away from the casualty's face for three to four seconds

Look and listen for air movement

Give a total of two rescue breaths before recommencing chest compression

Keep performing resuscitation with a ratio of 30:2 (30 chest compressions to two rescue breaths) until:

The casualty starts breathing normally

You are physically exhausted

The emergency services arrive and take over.

• Clinical tip

• You can deliver mouth to mouth and mouth to nose rescue breaths more comfortably through a pocket mask or face shield. Many lay first aiders carry these in their cars or bags and, if you know how to use them, they can be a very useful tool.

9. After about 10 minutes, the ambulance arrives and the paramedics take over from you. One of the bystanders comments "You'd better hope he survives, or his relatives will have their lawyers after you." What is your legal position after attempting to rescue a stranger?

Your medical defence organisation will probably not cover you for Good Samaritan acts

The NHS will defend you for any litigation arising from a Good Samaritan act

If you made any mistakes during the resuscitation attempt, there is a high risk of you being sued

So long as you acted reasonably and did your best, the risk of you being sued is minimal

So long as you acted reasonably and did your best, the risk of you being sued is minimal

A Good Samaritan act is defined by the Medical Protection Society as: "the provision of clinical services related to a clinical emergency, accident, or disaster when you are not present in your professional capacity but as a bystander."People may be concerned about providing basic life support in the pre-hospital environment in case they are held liable. The difference between General Medical Council standards and the demands of the law adds to this uncertainty.

The General Medical Council expects all doctors to offer assistance in an emergency, but only:

Within the limits of their competence

If it is safe to do so

If there is no one else better qualified to help.

Doctors are not all expected to have the same level of competence in an emergency so, for example, a retired GP and consultant in emergency medicine would be judged by different standards.

In contrast, English law does not recognise a "duty to rescue," and no legal liability arises from walking past an emergency. But as soon as you step in, this establishes a duty of care. The casualty could then bring an action against you if they suffer any harm caused by you failing in this duty. In practice, so long as you act reasonably and recognise your own limits, it is unlikely that any legal action would be taken against you. As soon as practical after the event, you should make a record of your observations and actions. If possible, you should give this to the ambulance crew to go into the patient's records.

Most medical defence organisations will provide assistance for members if a claim is made against them, anywhere in the world, for a Good Samaritan act. The NHS Litigation Authority does not cover doctors for Good Samaritan acts, as they are not considered part of your contracted NHS duties.

Children and drowning victims

Cardiac arrests in children tend to be secondary to respiratory arrest.49-53 Because of this, resuscitation of children is slightly different to that in adults. Previously there were separate basic life support guidelines for children, but this tended to complicate teaching of the protocol. So the 2005 guidelines teach the adult sequence with paediatric modifiers.These modifications are also used for adults who have suffered a respiratory arrest; the most common cause being drowning. The resuscitation protocol has been modified for respiratory arrest because, in these instances, hypoxia is the reason for cardiac arrest rather than a consequence of it. Therefore, re-oxygenating the patient is a higher priority.

Modifiers for children and drowning victims:

Give five initial rescue breaths before starting chest compressions

Perform chest compressions for one minute before calling for an ambulance.

Clinical tip

Chest compressions in children should still aim to compress the rib cage by about one third.To achieve this, you should use:

Two fingers with an infant

A single hand for small children.

a : Assess the casualty’s airway

This is incorrect for two reasons. Firstly, because you would need to approach the casualty to assess their airway, and this could put you in danger. Secondly, the 2005 basic life support guidelines recommend that you simply open the airway, rather than try to assess it.b : Check the casualty for a pulse

Checking for a pulse is no longer part of the basic life support guidelines, as it was found to be unreliable.

c : Check for danger

Checking for danger is the first part of the basic life support sequence and is the most important. If there is a danger to you and you don’t check for it, you could easily become injured, and hence be unable to assist.

d : Phone 999 or 112 for help

You have not yet made a preliminary assessment of the situation, and could be making an unnecessary emergency call.

Which one of the following is the first thing you should do when faced with an emergency situation?

Your answer

Correct answer

a.

You should not move the casualty’s head at all

b.

You should perform a head tilt/chin lift

c.

You should perform a jaw thrust

d.

You should use an oral airway instead of moving the head

• You are teaching a Basic Life Support course to non-clinicians, and one of the audience asks how to open the airway of an unconscious casualty who you suspect may have injured his neck. Which one of the following is correct?

•

The airway is still vital even if there is a suspected cervical spine injury. If you have a trained assistant, you may attempt manual in line stabilisation of the casualty’s spine if it does not delay opening their airway unduly. But you should perform a head tilt/chin lift, even if a cervical spine injury is suspected. If you do not treat airway obstruction, the casualty will probably die.

You should perform a head tilt/chin lift

You should open the airway with a head tilt/chin lift. Although a jaw thrust may be used, this is difficult to learn and perform, so is not recommended for non-health professionals.24 Opening the airway of an unconscious casualty carries the risk of exacerbating a spinal injury, but not opening an obstructed airway could result in the casualty’s death.Jaw thrusts are not recommended for non-health professionals because they are difficult to learn and perform. A head tilt/chin lift is recommended. Both techniques cause similar amounts of movement of the spine.36 Opening the airway of an unconscious casualty carries the risk of exacerbating a spinal injury, but not opening an obstructed airway is almost certain to result in the casualty’s death.