د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE

• For many years doctors have tried to use the available evidence when making decisions about the use of drugs or other therapeutic measures; this started happening as long ago as the 18th century and perhaps before. However, in the early 1990s it was pointed out that the ways in which they did so were somewhat haphazard. For example, treatment strategies would often be formulated in unsystematic reviews of the published data, using selected pieces of evidence that experts in the field judged to be the most valuable or relevant. Inevitably, bias crept in when such judgements were made.• The discipline of evidence-based medicine was therefore invented in order to introduce a more systematic approach to the use of evidence in making therapeutic and other decisions

• This was made possible by:

• the development of statistical techniques for the systematic analysis of data

• the realisation that it was important to analyse all the available data, both published and unpublished

• the development of computerised databases of relevant information, linked to methods by which that information could be traced.

• The tenets of evidence-based medicine are that well-formulated questions about medical management, including diagnosis and therapy, can be answered by:

• carrying out high-quality, randomised, controlled clinical trials

• tracing all the available evidence

• analysing the evidence systematically

• determining how valid and useful the evidence is

• applying the evidence to the management of the individual patient.

• Although there are well-established methods for carrying out the first four of these procedures, it is the last that is the most important and the most difficult. This is because the evidence on which decisions are made is usually derived from large populations, which may not have included patients like those the prescriber wants to treat; even if the trials were representative of such patients, there is so much interindividual variability that mean values taken from studies of populations may not be applicable to individuals. Methods for dealing with this are available, but are not as well developed or easily applied as the methods for obtaining the evidence. In addition, there are many therapeutic problems for which adequate evidence is not available at all; in such cases one uses what evidence there is, indifferent though it may be.

EBM

Clinicians must base their practice on the best available evidence. This need to be up to date, relevant,authoritative & easily accesible

This tutorial includes five major units. We recommend that you go through them in sequence. They will give you an overview of the Evidence-Based Medicine process as well as give you an opportunity to practice with new cases. The five units are:

• What is Evidence Based Medicine

• provides definitions and explains the steps in the EBM• process.

• The Well-Built Clinical Question

• introduces you to a patient, illustrates the anatomy of a

• good clinical question, and defines the types of

• questions and studies.

• Literature Search

• constructs a well-built literature search and identifies

• potentially relevant articles.

• Evaluating the Evidence

• identifies criteria for determining the validity of a study.

• Testing your Knowledge

• gives you an opportunity to practice the EBM process

• with several new cases.

What is Evidence-Based Medicine

Objectives:

From this tutorial you will learn:

How EBM is defined

About clinical evidence resources

The scope of EBM practice

The steps in the EBM process

1-Boston-univ-2006

What is Evidence-Based MedicineHere's how the literature defines EBM

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been described as "the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients." It is a method of solving clinical problems that stresses the examination of clinical research rather than relying on intuition and clinical experience alone.

The need for EBM

Medical research is continually discovering improved treatment methods and therapies .Research findings are often delayed in being implemented into clinical practice.Clinicians must stay current with changing therapies. Evidence-based practice has been shown to keep clinicians up to date

2-Boston-univ-2006

Clinical Evidence ResourcesWhere do you find information to answer

your clinical questions?

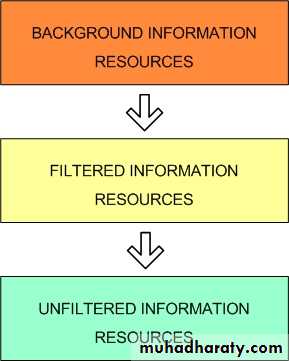

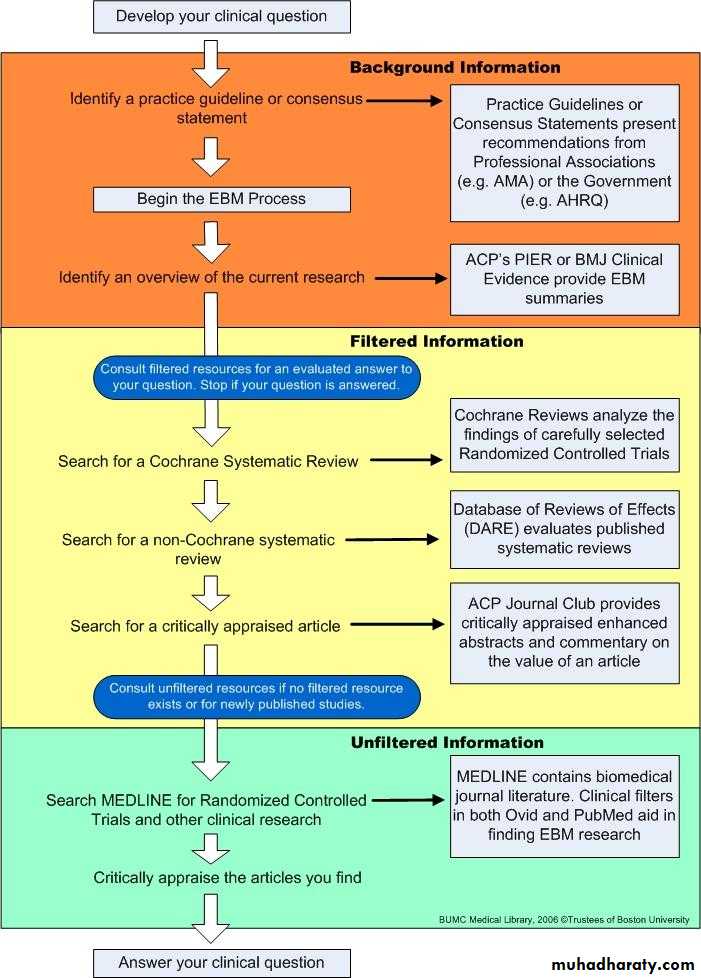

3-1

EBM resources can provide

A current overview of a subject

A critical appraisal of the literature

A review and synthesis of the research on a topic

A comparison of emerging treatment options to the gold standard treatment

In addition to published journal literature, there are a number of subscription resources available from the BUMC Library to aid you in accessing research-based clinical evidence.

Clinical Evidence Resources

4-1

5-1

Where do I start?

Background Information Resources are a great place to start the EBM process. They provide broad overviews of medical topics, which help increase your understanding of the topics and acquaint you with the related evidence-based literature.Examples of Background Information Resources:

Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines and Consensus Statements Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines and Consensus Statements are carefully considered treatment guidelines, often published and updated by government or professional associations, that represent the preferred or gold standard treatment strategies for common diseases.

6-1

Background Information Resources

I have the background information down. Now what?

Once you have a solid understanding of your topic next investigate Filtered Information Resources. These resources sometimes also called "digested" or "synthesized" resources are structured to save you time and effort by providing varying levels of analysis.Examples of Filtered Information Resources:

Cochrane Systematic Reviews Cochrane Systematic Reviews utilize stringent and explicit methods to collect, critically appraise, and succinctly summarize the best available medical literature, including individual studies. Generally Cochrane Systematic Reviews answer a specific clinical question.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews provides full-text access to Cochrane Systematic Reviews

Non-Cochrane Systematic Reviews A Systematic Review in general is "an overview of primary studies that used explicit and reproducible methods".1

The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) critically assesses systematic reviews from a variety of medical journals.

Critically Appraised ArticlesCritically Appraised Articles analyze a single research article, judge its validity, and publish an enhanced abstract of the article.

ACP Journal Club offers enhanced abstracts of studies identified as being methodologically sound and clinically relevant

7-1

Filtered Information Resources

Unfiltered Information Resources

There was no Filtered Information on my topic. What next?If there is no filtered information on your topic or that fits your specific patient you will need to utilize individual journal articles and studies. However, because generally journal articles and studies are not evaluated you will need to analyze your found articles and studies to determine their quality.

Examples of Unfiltered Information Resources:

Journal ArticlesResearch articles found in journals often investigate one topic in detail and require critical evaluation on the reader's part.

MEDLINE is the premier source for biomedical journal articles. MEDLINE is available through BUMC MEDLINE Plus/Ovid or PubMed.

Randomized Controlled TrialsRandomized Controlled Trials (RCT) randomly assign participants into control or experimental groups to provide unbiased assessment of an intervention.

When using MEDLINE you are able to restrict your searches to RCTs.

8-1

• Unfiltered Information Resources

9-1

Examples of Evidence-Based Activities at BUMC

School of Dental MedicineEvidence-Based Curriculum

Alcohol Clinical Training Project

EBM based curriculum

An online EBM Newsletter (Alcohol and Health: Current Evidence)

Journal Club

Department of Microbiology Journal Club

Family Medicine Clerkship

EBM based curriculum

EBM literature searching skills workshop

Gastroenterology Journal Club

Geriatrics

Evidence-based medicine training module

Evidence-based Geriatrics Case Conference

Immunology Training Program Journal Club

10-1

• Where is EBM Practiced?

PROBLEM: Practitioners must deal with an explosion of available medical literature.

FACT: In order to keep up with the 7,827 relevant articles published monthly, a family medicine physician would need to dedicate 627.5 hours to reading the medical literature.1EBM SOLUTION: Consulting critically appraised evidence-based review resources helps reduce the necessary time expended on collecting, reading, and evaluating medical literature.

EBM RESOURCE: The ACP Journal Club provides access to succinct enhanced abstracts for individual articles and studies that are indentified as being methodologically sound and clinically relevant.

-11-1

Why Practice EBM?PROBLEM: Practitioners must keep up to date with current research.

FACT: Medical research is continually discovering improved treatment methods and therapies.EBM SOLUTION: Practicing EBM helps keep practitioners up to date on current evidence and practice guidelines.

EBM RESOURCE: ACP PIER (Physicians' Information and Education Resource), an electronic evidence-based textbook, provides easy access to continually updated clinical evidence.

12-1

Why Practice EBM?

PROBLEM: Research findings are often delayed in being implemented into clinical practice.

FACT: Did you know that it takes on average 17 years for clinical research to be fully integrated into everyday practice.1FACT: Prior to the early 1990's, it was recommended that infants sleep on their stomachs despite evidence available in the 1970's that this contributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).2

EBM SOLUTION: The constant advancement and development of EBM resources, which take into account evidence from a wide variety of fields, provide clinicians with the opportunity for greater exposure to clinical evidence.

EBM RESOURCE: The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews provides access to highly developed systematic reviews that integrate evidence from a broad spectrum of resources and that critically appraise and succinctly summarize the best available medical literature.

-1

• Why Practice EBM?

PROBLEM: Research findings are often delayed in being implemented into clinical practice.FACT: Did you know that it takes on average 17 years for clinical research to be fully integrated into everyday practice.1

FACT: Prior to the early 1990's, it was recommended that infants sleep on their stomachs despite evidence available in the 1970's that this contributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).2

EBM SOLUTION: The constant advancement and development of EBM resources, which take into account evidence from a wide variety of fields, provide clinicians with the opportunity for greater exposure to clinical evidence.

EBM RESOURCE: The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews provides access to highly developed systematic reviews that integrate evidence from a broad spectrum of resources and that critically appraise and succinctly summarize the best available medical literature.

13-1

Why Practice EBM?

• PROBLEM: Lack of familiarity with primary research can result in unnecessary clinical trials and possible harm to research subjects.1

• FACT: 64 clinical trials involving the drug Aprotinin between 1987 and 2002 continuously found that the drug lessened bleeding during surgery, but only 20% of previous studies were cited by researchers.2 Because later researchers were unaware of research that came before, they may have denied a proven therapy to a control group.

• EBM SOLUTION: A careful and critical literature review should be carried out prior to engaging in clinical research.

• EBM RESOURCE: Medline (Ovid or PubMed) searching with the results limited to Clinical Trials will provide a fairly complete representation of previously completed clinical research

14-1

Why Practice EBM?Formulating a Clinical Question

Objectives:From this tutorial you will learn:

The impact of the clinical question on EBM research

The key elements of a clinical question

How to form an answerable clinical question

The role of the clinical question in the overall EBM

process

1-2

The Clinical Question

Formulating a clinical question is the first step in the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) process2-2

• Make sure you start with a well-developed and

• answerable question.• A good clinical question will:

• Save time when researching

• Keep the focus directly on the patient's need

• Suggest the appropriate form that a useful answer may take

• Not: Your clinical situation may raise more than one question. Don't try to squeeze multiple topics into one clinical research question

3-2

• Case:

• You examine a five-year old Asian American female, Junko Morioka, in your office and determine that she is suffering from Acute Otitis Media. Her mother mentions that Junko seems to get these ear infections every once and a while and that sometimes they "just go away" and other times Junko seems to need antibiotics. Junko's mother is worried about Junko developing a resistance to all these antibiotics and wonders aloud if antibiotics are really necessary.• Here are two well-formulated clinical questions that a physician might research based on the case above.

• Among children with Acute Otitis Media, does treatment with oral antibiotics result in significant improvements in symptoms, and reduction in complications of AOM, as compared to no treatment?

• OR, to what extent does treating children with AOM with repeated oral antibiotic therapy promote antibiotic resistance?

Your Clinical Question

4-2

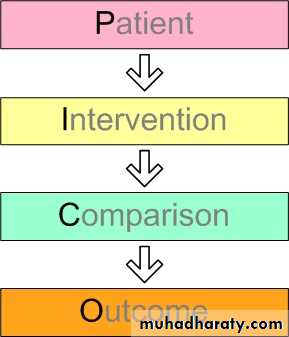

A clinical question has four major elements

5-2

PICO, was originally defined by physicians at McMaster University in the early 1990's

P is for Patient

• A clinical question must identify a patient or patient group. Additionally a clinical question should include any information that is relevant to the treatment or diagnosis or the patient.• For example, you might include the patient's:

• Sex, age or race

• Disease History

• Primary Complaint

•

6-2

What is the Intervention

• The intervention is what you plan to do for your patient or patient group.

• For example, you might:

• Run tests

• Prescribe drug treatment

• Refer to a specialist

• Schedule sugery

7-2

PICO

Next C is for ComparisonWhat is the Comparison

In general most, but not all, clinical questions have a comparison. A comparison is the alternative that you want to compare to your intervention.

For example:

Is aspirin as effective in preventing strokes as warfarin ?

Is chicken soup as effective as bed rest in treating a cold

8-2

What is the Outcome?

The outcome is the hoped for

effect of the intervention.

For example:

If I prescribe ibuprofen for my patient it will prevent pain. Outcome = Pain prevention.

9-2

O is for Outcome

You determined the following were important factors for our

casePatient:

Intervention:

Comparison:

Outcome:

Case:

You examine a five-year old Asian American female, Junko Morioka, in your office and determine that she is suffering from Acute Otitis Media. Her mother mentions that Junko seems to get these ear infections every once and a while and that sometimes they "just go away" and other times Junko seems to need antibiotics. Junko's mother is worried about Junko developing a resistance to all these antibiotics and wonders aloud if antibiotics are really necessary.

Put your PICO elements together to form an researchable clinical question. [

10-2

• Among children with Acute Otitis Media, does treatment with oral antibiotics result in significant improvements in symptoms, and reduction in complications of AOM, as compared to no treatment ?

• OR to what extent does treating children with AOM with repeated oral antibiotic therapy promote antibiotic resistance?

11-2

Here are two well-formulated clinical questions that a physician might research based on the case above.

EBM Resources on the Net

We have presented a selection of web sites of groups which are actively involved in promoting EBHC around the world, as well as a selection of content sites which contain evidence-based summaries of clinical research. The Centre cannot accept responsibility for the content of these sites (but we do like them (Evidence-Basaed Health Care

Non-English language EBHC sites

Journal Clubs and Evidence Summaries on the Web

Information: Finding the Evidence.

Evidence-Based Health Care

Bandolier.CASP: The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Centre for Statistics in Medicine in Oxford

Centre for Evidence-Based Child Health in London

Centre for Evidence-Based Dentistry in Oxford

Centre for Evidence-Based Dermatology in Nottingham

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Mount Sinai, Toronto, including packages on practising EBM

Centre for Evidence-Based Mental Health in Oxford

Centre for Evidence-Based Nursing in York

Centre for Evidence-Based Pathology in Nottingham

Centre for Evidence-Based Physiotherapy in Sydney

Centres for Health Evidence, in Canada, where they have loads of EBH resources, including critical appraisal worksheets and the JAMA Guides

CHAIN, a multidisciplinary network of people working in health and social care.

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) Centre, based at the Institute of Education in London, focusing on health and education policy makers

Evidence-Based Social Policy, ESRC Collaboration in the UK

Cochrane Collaboration, core content for The Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

Berkeley Systematic Reviews Group, with training and guidelines on how to conduct systematic reviews

HIRU - The Health Informatics Research Unit, at McMaster University's Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics in Canada, featuring a large inventory of evidence based resources and an on-line database.

The NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York

Clinical Practice Innovation, a toolkit and other practical resources to help clinicians improve their own practice and that of their teams and peers, run by Centre member Jeremy Wyatt and his colleagues at UCL

definition

EBM is "the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient.

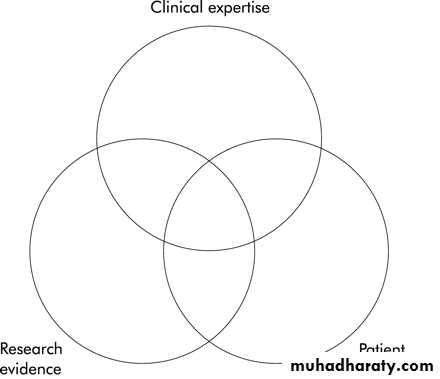

It means integrating individual clinical expertise(clinician's cumulated experience, education and clinical skills ) with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.

EBM." requires new skills of the clinician, including efficient literature-searching, and the application of formal rules of evidence in evaluating the clinical literature.

The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgement that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available external clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centred clinical research into the accuracy and precision of diagnostic tests (including the clinical examination), the power of prognostic markers, and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive regimens. External clinical evidence both invalidates previously accepted diagnostic tests and treatments and replaces them with new ones that are more powerful, more accurate, more efficacious, and safer.

Some fear that evidence based medicine will be hijacked by purchasers and managers to cut the costs of health care. This would not only be a misuse of evidence based medicine but suggests a fundamental misunderstanding of its financial consequences. Doctors practising evidence based medicine will identify and apply the most efficacious interventions to maximise the quality and quantity of life for individual patients; this may raise rather than lower the cost of their care.

The American health-care system’ is among the best in the world. Certainly we

have the most technologically advanced system.We also spend the most money.Are we getting our money’s worth?

Are those of our citizens who have adequate access to health care getting the best possible care?

What is the best possible health care and who defines it?

Scenario

You are caring for a 68 year old man who has hypertension (intermittently controlled) with a remote gastrointestinal bleed and non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) for 3 months, and an enlarged left atrium (so cardioversion is unlikely).The patient has no history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack. His father experienced a debilitating stroke several years ago and when he learns that his atrial fibrillation places him at higher risk for a stroke, he is visibly distressed.

Early model of the key elements for evidence-based clinical decisions

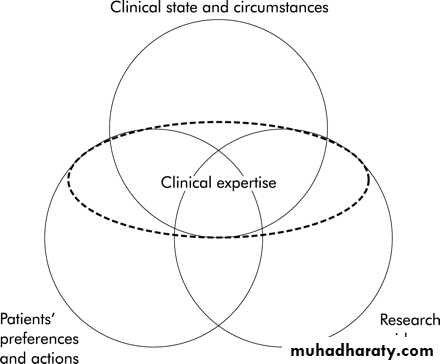

EBM based on patients' circumstances, patients' preferences and actions, and best research evidence, with a central role for clinical expertise to integrate these components.

Initially, evidence-based medicine focused mainly on determining the best research evidence relevant to a clinical problem or decision and applying that evidence to resolve the issue.

Subsequent versions of evidence-based decision making have emphasised that research evidence alone is not an adequate guide to action. Rather, clinicians must apply their expertise to assess the patient's problem and must also incorporate the research evidence and the patient's preferences or values before making a management recommendation ,

In Figure 2 , the "clinical state and circumstances" of the patient replace "clinical expertise" as one of the key elements in clinical decisions; "patient preferences" is expanded to include patients' actions and is reversed in position with "research evidence", which signifies its frequent precedence.

updated model for evidence-based clinical decisions

Clinical state and circumstances

• For example, people who find themselves in remote areas when beset by crushing retrosternal chest pain may have to settle for aspirin, whereas those living close to a tertiary care medical centre will probably have many more options• Similarly, a patient with atrial fibrillation and a high bleeding risk,, may experience more harm than good from anticoagulation treatment, whereas a patient with a high risk for stroke and a low risk for bleeding may have a substantial net benefit from such treatment.

• These states and circumstances can often be modified, for example, by improving the benefit : risk ratio by closer anticoagulant monitoring; thus, an "evidence-based" decision about anticoagulation for a patient with atrial fibrillation is not only determined by the proven efficacy of anticoagulation and its potential adverse effects, but it will also vary from patient to patient according to individual clinical circumstances.

Patients' preferences and actions

Patients may have either no views or unshakable views on their treatment options, depending on their condition, personal values and experiencesResearch evidence

Research evidence includes systematic observations from the laboratory, preliminary pathophysiological studies in humans, and more advanced applied clinical research, such as randomised controlled trials with outcomes that are immediately important to patients.much of the innovation is of marginal advantage at best, is often expensive, and often invokes risk for the patient even as it conveys benefit.

For example, a systematic review of trials of anticoagulant and antiplatelet interventions for NVAF documents a 62% relative risk reduction for stroke from warfarin, offset by a 50% relative risk increase for major bleeding.

Aspirin reduces the relative risk for stroke by 22%, but without a statistically significant increase in the risk for bleeding.

Within these trials it is possible to identify subgroups of patients for whom the risk for stroke varies according to several factors, including age, history of hypertension, diabetes, and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack

"Personalising" the evidence to fit a specific patient's circumstances is a key area for development in evidence-based medicine. Notably, research evidence is often available to assist with the quantitative interpretation of the patient's clinical circumstances

The expanded role of clinical expertise

Clinical expertise includes the general basic skills of clinical practice as well as the experience of the individual practitioner. Clinical expertise must encompass and balance the patient's clinical state and circumstances, relevant research evidence, and the patient's preferences and actions if a successful and satisfying result is to occur.The varying role of the 4 components in individual clinical decisions

The model can accommodate different weights for each component of the decisionIn the "average" older patient with atrial fibrillation and 1 or 2 additional risk factors for stroke, but without excess risk for bleeding, the large relative risk reduction in stroke with warfarin may be the primary determinant of patient management. In a patient unwilling to have regular monitoring of anticoagulation status, patient preferences will dominate. It is undoubtedly true that the expertise of clinicians varies. For a patient living in a remote area, with limited access to anticoagulant monitoring or care for complications .circumstances — may dominate the clinical decision.

Application to individual patients

For our patient, the evidence could be (briefly) summarised as follows.If you take warfarin, 1 tablet a day, with weekly blood checks to guide the dose, your risk for stroke in the first year will decrease from 6% (6 in 100) to 2.3% (about 2 in 100).

Half of strokes caused by atrial fibrillation will be "major", resulting in permanent disability, and half will be "minor", allowing the person to function independently.

The anticoagulant will also increase your risk for major bleeding from 1% to 8%. If you take aspirin, 1 tablet a day, instead of warfarin, you will have no need for blood tests to monitor the dose concentration and your risk for stroke will decrease from 6% to 4.7%, without an appreciable increase in your risk for major bleeding. By major bleeding, we mean the loss of at least 2 units of blood in 7 days or any life threatening bleeding.

Some limitations of the proposed model

Our model does not depict all of the elements involved. For example, we have not included the important roles that society and healthcare organisations play in providing and limiting resources for health services.Rather, our focus has purposely been on the decisions made by patients and their immediate healthcare providers,

It is also impossible to implement the model as prescribed. For example, at present, it is not possible to make an accurate prediction of the patient's likelihood of following a treatment programme of anticoagulation and monitoring.

Thus, our model is conceptual rather than practical and remains under development.

Conclusions

As we continue our journey through the era of research-informed health care, the benefits that our patients will receive and our satisfaction with our own clinical performance will depend increasingly on making care decisions that incorporate the clinical state and circumstances of each patient, their preferences and actions, and the best current evidence from research that pertains to the patient's problem.

The nature and scope of clinical expertise must expand to balance and integrate these factors, dealing with not only the traditional focus of assessing the patient's state but also the pertinent research evidence and the patient's preferences and actions before recommending a course of action

Does teaching and learning evidence-based medicine improve patient outcomes?

Our advocating evidence-based medicine in the absence of definitive evidence of its superiority in improving patient outcomes may appear to be an internal contradiction. As has been pointed out, however, evidence-based medicine does not advocate a rejection of all innovations in the absence of definitive evidence. When definitive evidence is not available, one must fall back on weaker evidence and on biologic rationale. The rationale in this case is that physicians who are up-to-date as a function of their ability to read the current literature critically, and are able to distinguish strong from weaker evidence are likely to be more judicious in the therapy they recommend.Until more definitive evidence is adduced, adoption of evidence-based medicine should appropriately be restricted to three groups. One group is those who find the rationale compelling, and thus believe that use of the evidence-based medicine approach is likely to improve clinical care. A second group is those who have the energy, enthusiasm, and resources to test evidence-based medicine in educational trials. A final group include those who, while sceptical of improvements in patient outcome, believe it is very unlikely that deterioration in care results from the evidence-based approach and who find that the practice of medicine in the new paradigm is more exciting and fun.

Requirements for the Practice of Evidence-Based Medicine

The role-modelling, practice, and teaching of evidence-based medicine requires skills that are not traditionally part of medical training.These include precisely defining a patient problem, and what information is required to resolve the problem; conducting an efficient search of the literature; selecting the best of the relevant studies, and applying rules of evidence to determine their validity; being able to present to colleagues in a succinct fashion the content of the article, and its strengths and weaknesses; extracting the clinical message, and applying it to the patient problem.

We will refer to this process as the "critical appraisal exercise."

Evidence-based Medicine in a Medical Residency

The Internal Medicine Residency Program at McMaster University has an explicit commitment to producing practitioners of evidence-based medicine. While other clinical departments at McMaster have devoted themselves to teaching evidence-based medicine, the commitment is strongest in the Department of Medicine. The residents spend each Wednesday afternoon at an "academic half-day." At the beginning of each new academic year, the rules of evidence which relate to articles concerning therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, and overviews are reviewed. In subsequent sessions, the discussion is built around a clinical case, and two original articles which bear on the problem are presented. The residents are responsible for critically appraising the articles, and arriving at bottom lines "" regarding the strength of evidence and how it bears on the clinical problem. They learn to present the methods and results in a succinct fashion, emphasizing only the key points. A wide-ranging discussion, including issues of underlying pathophysiology and related questions of diagnosis and management, follows presentation of the articles. The second part of the half-day is devoted to the physical examination. Clinical teachers present optimal techniques of examination with attention to what is known about their reproducibility and accuracy.Facilities for computerized literature searching are available .Research in our institution has shown that MEDLINE searching from clinical settings is feasible with brief training .

A subsequent investigation demonstrated that internal medicine house staff who have computer access on the ward and feedback concerning their searching do an average of over 3.6 searches per month .

House staff believe that over 90% of their searches that are stimulated by a patient problem lead to some improvement in patient care

• Assessment of searching and critical appraisal skills is being incorporated into the evaluation of residents.

• We believe that the new paradigm will remain an academic mirage with little relation to the world of day-to-day clinical practice unless physicians-in-training are exposed to role models who practice evidence-based medicine. One focus of recruitment for our Department of Medicine has been internists with training in clinical epidemiology... To help attending physicians improve their skills in this area, we have encouraged them to form partnerships which involve attending the partner's clinical rounds, making observations, and providing formal feedback.

• One learns through observation and through criticisms of one's performance. A number of faculty members have participated in this program.

Barriers to Teaching Evidence-Based Medicine

Difficulties we have encountered in teaching evidence-based medicine include the following.Many house staff start with rudimentary critical appraisal skills and the topic may be threatening for them.

People like quick and easy answers. Cookbook medicine has its appeal. Critical appraisal involves additional time and effort, and may be perceived as inefficient and distracting from the real goal (to provide optimal care for patients).

For many clinical questions, high quality evidence is lacking. If such questions predominate in attempts to introduce critical appraisal, a sense of futility can result.

The concepts of evidence-based medicine are met with scepticism by many faculty members who are therefore unenthusiastic about modifying their teaching and practice in accordance with its dictates.

These problems can be ameliorated by use of the strategies on effective teaching of evidence-based medicine.“and further reduced by the attending physician role-modelling the practice of evidence-based medicine. Inefficiency can be reduced by teaching effective searching skills and simple guidelines for assessing the validity of the papers. In addition, one can emphasize that critical appraisal as a strategy for solving clinical problems is most appropriate when the problems are common in one's own practice..

Many problems in the practice and teaching of evidence-based medicine remain. Many physicians, including both residents and faculty members, are still sceptical about the tenets of the new paradigm.

Virginia Commonwealth University | Libraries VCU

Evidence-Based MedicineResource Guide

Databases

1- Cochrane Library VCU The Cochrane Library provides access via the web to reliable information compiled by the Cochrane Collaboration, an international network of individuals and institutions committed to preparing, maintaining, and disseminating systematic, up-to-date reviews of the effects of health care. The Cochrane Library has four distinct databases, all of which are searched simultaneously:The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness

The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register

The Cochrane Review Methodology Database

2- PubMed VCU The PubMed search system is one of many ways to access and search MEDLINE, the National Library of Medicine's premier bibliographic database covering the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and the preclinical sciences. The MEDLINE file contains bibliographic citations and author abstracts from over 4,000 current biomedical journals published internationally. The file contains more than 14 million records dating back to the 1950s. Special features on PubMed include:

Clinical queries for identifying systematic reviews or relevant studies on therapy, diagnosis, etiology, and prognosis

Links to full-text articles from publishers websites (note: a fee or subscription is often required)

Identification of publication types such as reviews, meta-analyses and practice guidelines

3- HSTAT: Health Services/Technology Assessment Text HSTAT is a free searchable database of full-text documents from health-related government agencies, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Users can browse for documents by category or search by keyword. 3

practice guidelines

National Guideline Clearinghouse A comprehensive database of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and related documents. Search or browse by disease, treatment/intervention or organization. Citations and abstracts are provided for all guidelines, with links to full-text or information about print copies. Produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in partnership with the American Medical Association and the American Association of Health Plans.

Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines

An extensive list of guidelines grouped by clinical content for primary care providers. Personal website produced by Peter Sam, M.D., School of Medicine, University of California at San Francisco.

electronic journals

ACP Journal ClubBandolier

Critical Pathways in Cardiology

EBM Online

Evidence-based Cardiovascular Medicine VCU

Evidence-based Healthcare VCU

Evidence-based Mental Health VCU

Evidence-based Nursing VCU

Evidence-based Obstetrics and Gynecology VCU

Evidence-based Oncology VCU

guides and tutorials

Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (U.K( Based in Oxford, the Centre provides a rich resource of tools and information for learning and practice of EBM.Evidence Based Health Care Guide to Internet resources on EBM produced by the HealthWeb project.

Evidence-Based Medicine Excellent collection of resources and information developed by Duke University Medical Center Library.

Evidence Based Medicine: Finding the Best Clinical Literature Tutorial from the University of Illinois at Chicago with good examples of MEDLINE searches.

Netting the Evidence: A ScHARR Introduction to Evidence Based Practice on the Internet Massive list of links to EBM websites including tutorials, journals, organizations, software, etc.

Users' Guides to Evidence-Based Practice A collection of the working documents behind the "Users' Guides to the Medical Literature" series from JAMA on how to use research articles in caring for patients

Despite its ancient origins, evidence-based medicine remains a relatively young discipline whose positive impacts are just beginning to be validated, and it will continue to evolve. This evolution will be enhanced as several undergraduate, post-graduate, and continuing medical education programmes adopt and adapt it to their learners’ needs. These programmes, and their evaluation, will provide further information and understanding about what evidence-based medicine is, and what it is not

Putting evidence into context: some advice for guideline writers

INTRODUCTIONEvidence-based medicine (EBM) has been defined as the "integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values Though a laudable ideal, it is not feasible for individual clinicians to review, interpret, and apply all relevant evidence all the time. Hence clinicians should have access to "a set of tools and resources for finding and applying current best evidence from research for the care of individual patients The goal of clinical guideline writers is to perform part of this role, but they too must resolve these practical challenges if they are to provide tools to help clinicians deliver real evidence-based practice. Here we consider some challenges for guideline writers when producing clinical advice that meets the demands of busy clinicians2007

INTERPRETATION AND APPLICATION OF EVIDENCE

Knowledge to support decision making may be derived from published research, locally generated data, clinician experience, the law, and patient perspectives. Each can be regarded as "supporting evidence,"The availability of evidence may, of itself, distort practice. EBM is highly dependent on the generators of research evidence whose goals are not generally consistent with the users of research evidence. Trials are costly and are mostly undertaken by the pharmaceutical industry, so health care may become captured by the pharmaceutical industry. More specifically, published clinical trials tend to represent a biased (positive) sample of the total data pool. Trials with significantly positive results are more likely to be published—and be published earlier Caution is required in interpretation of truncated RCTs: trials that are stopped earlier than planned because of an apparent benefit often overestimate the benefit and underestimate the harm of interventions. Results from trials funded by pharmaceutical companies tend to be "more positive" than those funded by "independent" sources.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR GUIDELINES WRITERS

We believe guideline writers must address 6 issues if they wish their product to be used to improve clinical practice1. Use the best available evidence

a few small, poor quality RCTs might result in a level 1 ranking, but a single, large, well conducted, multisite RCT would only merit a level 2 ranking.

Hence level alone should not be used to grade evidence but rather should be the starting point for a more thorough appraisal that includes the quality and size of the study, and the size and relevance of the effects.

2. Harness a diversity of expertise and opinion

• The translation of evidence into recommendations• Is Not straightforward; evidence can be interpreted

• In Different ways dependent on mindsets and

• experiences.

• Even when there is very good evidence, different

• experts may synthesise it to produce various

• conclusions about optimal therapy.

3. Allow users to fit advice to the individual patientand context

published guidance needs to be flexible and adaptable to various clinical contexts.Guidelines should provide information that can be integrated with individual clinical expertise so that clinicians can make decisions about whether and how it matches the patient’s clinical state, predicament, and preferences, and thus whether it should be applied.

4. Balance simplicity, flexibility, and completeness

The most helpful clinical information is problem-oriented.

While based on the best available evidence, it focuses on

the problems seen in day-to-day practice. Usability of the

information and its potential integration into the clinical

workflow is critical. To meet these criteria, guidelines

Should be readable and easy to use, and be available in

Different forms for different groups of users (eg,

handbooks, electronic versions for desktop computers,

and handheld computers).

5. Build trust through quality, transparency, andindependence

The response of clinicians to information is influenced by the trust clinicians have in that information. Factors that influence trust in the information are the integrity and the reputation of the organisation publishing the information. Information from government could be perceived as promoting the government agenda; information from the pharmaceutical industry could be thought to accentuate the benefits, or minimise the adverse qualities, of a particular drug therapy. The process by which the guidance is developed is critical to its level of trust.More reliance would be given to information developed by a panel of independent experts who followed a rigorous, exhaustive, well documented, and tested process.

6. Give specific, but not constraining, guidance

Implementation of guidelines is variable. Studies assessing the effectiveness of different strategies for implementation of guidelines have shown modest effects and no clear pattern of results depend on a vast array of factors relating to guideline credibility, availability, accessibility, complexity, and applicability; and clinician awareness, memory, acceptance, and trust as well as opportunity, motivation, and capacity to use the guideline appropriately. Specific recommendations for action increase understanding of what needs to be done, improverecall of what should be done For example, the Therapeutic Guidelines usually provide several options for treatment, but for each option, specific generic names, doses, and durations are given.

CONCLUSION

It is not possible for an individual clinician to ‘‘become responsible for integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values’’ without tools that can provide information that is problem-based and focuses on the problems seen in day-to-day practice.Neither clinical trials nor meta-analyses can themselves provide the practical clues needed to implement their findings. And data provided by government or the pharmaceutical industry may not necessarily be trusted.

We believe that well produced, independent clinical practice guidelines that are trusted and provide integrated evidence in a clinical context offer clinicians the best chance of getting reliable support for decision making in clinical practice.

adding weak diagnostic information to good

information can degrade the overall performance: as

we add items to a clinical prediction rule accuracy

initially improves but then begins to get worse as we

add weaker information.

The poor information pollutes the good. Statisticians

call this "overfitting" of a model.

Coeliac disease often goes undetected, particularly in

Older patients with milder forms of the disease. SoBeing alert for the possibility and having a simple

approach to testing is worthwhile. Hopper categorised

patients with weight loss,anaemia, or diarrhoea as

having a "high risk”of coeliac disease, and added to this

the tissue Transglutaminase.Around a third of high risk

patients with a positive tissue transglutaminase

anitbody test had coeliac disease, whereas

if both were negative none had it.

9-question tool for predicting which patients

with undifferentiated arthritis are most likely todevelop rheumatoid arthritis.

Given the benefits of early disease modifying anti-

rheumatic drugs, it would be worth following such

patients more closely.

Therapy

• Ask a question

• Acquire some articles

• Appraise the evidence

• Apply the findings

• Assess your performance

Repeat – SPIRAL learning

Five steps

Main learning area highlighted

Then …

Describe clinical scenario

Story of a baby irrascible, unsettled, crying awkwardly and ?drawing up legs/pulling at ears

Typanic temperature 37.4 but looked slightly iffy. Repeated cases of tympanics being ??, esp. as new US colleague obsessed wqith sticking thermometers up bottoms.

Therapies

• To treat or not to treat?• Validity

• Importance

• Applicability

Explain there is a condition known as Higgenbottom’s Syndrome

Makes people drink excessive amounts of alcohol and fight in pubs

Trials recently with a therapy, Balay, which had been shown to look promising in animal experiments

A new paper published -J Dance Therapeutics - and you want to know if you invest in setting up the treatment programme

Validity - is the paper likely to be true

Importance - size of effect

Applicability - can it work for me/my setting

Therapies

• Was it randomised?

• Was the allocation concealed?

• Were the all the subjects analysed correctly?

• Was it blinded?

• Were the groups similar?

Validity

randomisation - bias concealment - bias

analysis - how many - 80% rule of thumb

why? Drop out make it insecure -- too bad to work through / side effects?

Psych -- new antipsychotic -- appears to work but V low follow up -- why? -- side effects intolerable, people stopped taking it and stopped attending medical clinics

ITT analysis - avoid the problems of having really bad ones transferred out of experimental group (or into experimental group)

Stroke / carotid trials -- swapped out of the surgery arm cause too crock

Neonates -- swapped into oscillatory ventilation as rescue strategy

blinding - diff twix blind and concealed

started equally - lots of very old people in a stroke trial? More boys in asthma?

treated equally - asthma trial - ventolin vs ventolin/atrovent -- if ventolin arm more got steroid then reduced effectiveness of ipratropium

Validity

Therapies

• Importance• What were the results?

• Over what time period?

• With what precision?

What were the results?

What was the outcome -- important?

How long did it take - esp important in comparisions

(talk about how later …)

What precision - ‘p’ vs CI Clinical and statistical significance

Therapies

• Number needed to treat

• Relative risk reduction

• Absolute risk reduction

• Event rates

Basic EBM number building block

NOT statistics - just adding up, taking away and dividing

back to Balay

draw table

Fighting Reading Camus

Balay 10 40

Normal 35 15

Therapies

• Event rates• n with event / total

• Control event rate (CER)

• Experimental event rate (EER)

Work though

EER (balay) = 0.2

CER (normal) = 0.7

Therapies

• Absolute risk reduction

• difference in two event rates

• CER - EER = ARR

• Relative risk reduction

• proportion of control rate

• CER-EER / CER = RRR

ARR = 0.7 - 0.2 = 0.5

RRR = 0.5 / 0.7 ~ 70%

Therapies

• Number needed to treat• number of extra patients you need to treat to prevent one bad outcome

• 1 / ARR = NNT

Fighting Reading Camus

Balay 1 49

Normal 3.5 46.5

EER = 0.02

CER = 0.07 RRR~70% ARR=0.05 NNT=20

Therapies

• 95% confidence interval• range within which the true value falls with 95% confidence

• use computer (e.g. CATMaker)

Point estimate of the truth

Assume the truth is out there

Bell shaped curve around the truth

95% why? Coins trick

Therapies

• Application

• Can it be applied to my patient?

• Can it be done here?

• How do patient values affect the decision?

Look at the differences between patients in trial and on street - too different? How different? - ‘f’

Is it feasible

Do values matter - and how much? - look at the LBHH

Therapies

• Is it valid?• Is it important?

• NNT for what

• over how long

• with what precision

• Does it apply?

Levels of Evidence

• Recommendation• Level of Evidence

• Type of Study

• A

• 1a

• Systematic review of RCTs

• 1b

• Individual RCT

• B

• 2a

• Systematic review of cohort studies

• 2b

• Individual cohort study• 3a

• Systematic review of case control studies• 3b

• Individual case control study• C

• 4

• Case series/case report

• D

• 5

• Expert opinion, bench research

Absolute Risk—> The risk our patient is facing!

• How likely is our patient to die (or have the outcome of interest) without intervention? = Control Event Rate (CER)

• consider this individual patient’s risk factors to estimate Patient Expected Event Rate = PEER.

• Absolute Risk usually increases with age.

• Improvement measured as Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)

Relative Risk Reduction:

• Usually reported in studies.• Ratio of the improvement of outcome over outcome without intervention (Rx):

• {Control Event Rate (CER) — Experimental Event Rate (EER)} / CER

• i.e. {CER-EER}/CER

• often independent of prevalence!

• often similar at different ages!

Our patient wants an absolute Risk Reduction (ARR):

• is a 40% reduction in Cardiac Risk worth taking pills daily for 10 years?? >vote!• if I have a 30% risk of MI or death {30 out of 100 people like me will suffer MI or death} in next 10 years > 40% RRR >> only 18 out of 100 will have MI or death. ARR = 12 out of 100! >>I like that!

• BUT if I have a 1% risk in 10 years, 40% less is a 0.6% risk >> hardly different!

Number Needed to Treat (NNT) (very trendy but tricky):

• only defined for specific prevalence-Patient’s Expected Event Rate=PEER!• only defined for a specific intervention!

• only defined for a specific outcome!

• eg. Pravastatin™ 40 mg nocte x10 years, in a 65 year old male, ex-smoker with high BP and Diabetes, to reduce MI or Death.

• NNT is the inverse of Absolute Risk Reduction: i.e. NNT = 1/ARR

Number Needed to Treat (NNT) for previous example:

• 12 fewer MI or death in 10 years per 100 persons treated: ARR=12/100

• NNT = 1/(12/100)=100/12= 8.3

• But the same Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) of 40% with a low prevalence:

• 0.4 fewer MI/death per 100 treated, ARR=0.4/100.

• NNT = 1/(0.4/100) = 100/0.4 = 250!

Why Odds Ratios? > compare results of different studies.

• consider 2x2 table:• RRR is (a-b/a) — but you can only go in rows within same study!

• Odds ratio is (a/c)/(b/d) = ad / bc — the individual ratios are in columns, and therefore are independent of the prevalence which is different in different studies.

• must use odds ratios to combine RCT’s

Odds Ratio (OR) to NNT — is the improvement worth the trouble?

• 1>OR>0, lower the OR = better the treatment (Rx) >> lower NNT.• for any OR, NNT is lowest when PEER=0.5

• estimate the PEER (patient’s risk)

• apply the OR to get patient's NNT.

Convert PEER & OR to NNT

Formula used in the table

Systematic Reviews

• Guides for appraisalWhat makes a Review “Systematic”?

• Based on a clearly formulated question• Identifies relevant studies

• Appraises quality of studies

• Summarizes evidence by use of explicit methodology

• Comments based on evidence gathered

Steps in a Systematic Review

• Framing the Question (Q)• Identifying relevant publications (F)

• Assessing Study quality (A)

• Summarising Evidence and interpreting finding (S)

Origin of Clinical Questions

• Diagnosis:• how to select and interpret diagnostic tests

• Prognosis:

• how to anticipate the patient’s likely course

• Therapy:

• how to select treatments that do more good than harm

• Prevention:

• how to screen and reduce the risk for disease

Step 1- Framing the Question (Q)

• Clear, unambiguous, structured question

• Questions formulated re:

• Populations of interest

• Interventions

• Control

• Outcomes

Unstructured Question

• Is self-management effective?• For what?

• For whom?

• Compared to what?

• What is meant by “effective”?

Structured Question

• Do adults (aged > 18) using oral anticoagulation therapy have fewer episodes of thrombotic events if they are self-managed than those that are managed by doctor/health practitioner?population

outcome

intervention

control

Step 2 – Identifying relevant publications (F)

Wide search of medical/scientific databases

Medline

Cochrane Reviews

Ovid

Relevance to focused question

Population of interest

Intervention of interest

Comparator of interest

Outcome of interest

The top 10 successes that we’ve had or seen in teaching EBM

• Teaching EBM succeeds:• When it centers around real clinical decisions

• When it focuses on learners’ actual learning needs

• When it balances passive with active learning

• When it connects new knowledge to old

• When it involves everyone on the team

Top 10 successes

• Teaching EBM succeeds:• When it matches and takes advantage of, the clinical setting, available time, and other circumstances

• When it balances preparedness with opportunism

• When it makes explicit how to make judgments, whether about the evidence itself or how to integrate evidence with other knowledge, clinical expertise and patient preferences

• When it builds learners’ lifelong learning abilities

Top 10 mistakes we’ve made or see when teaching EBM

• Teaching EBM fails:

• When learning how to do research is emphasised over how to use it

• When learning how to do statistics is emphasised over how to interpret them

• When teaching EBM is limited to finding flaws in published research

• When teaching portrays EBM as substituting research evidence for, rather than adding it to clinical expertise, patient values and circumstances

Top 10 mistakes

• Teaching EBM fails:• When it humiliates learners for not already knowing the ‘right’ fact or answer

• When it bullies learners to decide to act based on fear of others’ authority or power, rather than on authoritative evidence and rational argument

• When the amount of teaching exceeds the available time or the learner’s attention

Top 10 mistakes

• Teaching EBM fails:• When teaching with or about evidence is disconnected from the team’s learning needs about the patient’s illness or their own clinical skills

• When teaching occurs at the speed of the teacher’s speech or mouse clicks rather than the pace of the learner’s understanding

• When the teacher strives for full educational closure by the end of each session rather than leaving plenty to think about and learn between sessions

The question

• Does a normal ECG rule out a serious elevation of potassium?• Population - In suspected hyperkalemia

• Indicator - does a normal ECG

• Comparator -

• Outcome - rule out hyperkalemia?

What is EBHC?

• EBHC requires the integration of the best available research evidence with

• our clinical expertise and

• our patient’s unique values and circumstances

Its practice requires

• Asking• Acquiring

• Appraising

• Applying

• Assessing

A framework for teaching EBHC and evaluating our efforts

• Who is the learner?• What is the intervention?

• What are the outcomes?

Who is the learner?

• We must identify our learners, their needs and their learning styles• Learners include clinicians who want to practise EBHC and the patients they care for

• Do all clinicians want or need to learn how to practise all 5 steps?

What is the intervention?

• The 5 steps of practising EBHC – but what is the appropriate dose, formulation and amethod of delivery?

• 1 minute or 60 hours

• Journal clubs and/or freestanding courses

• At the bedside, in the classroom or online

What is a P-value?

I have found that many students are unsure about the interpretation of P-values and other concepts related to tests of significance.These ideas are used repeatedly in various applications so it is important that they be understood.

I will explain the concepts ingeneral terms first, then their application in the problem of assessing normality.We wish to test a null hypothesis against an alternative hypothesis using a dataset.

The two hypotheses specify two statistical models for the process that produced the data. The alternative hypothesis is what we expect to be true if the null hypothesis is false. We cannot prove that the alternative hypothesis is true but we may be able to demonstrate that the alternative is much more plausible than the null hypothesis given the data.

This demonstration is usually expressed in terms of a probability (a P-value) quantifying the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative.

RCT: Well conducted no bias

• 5 people with backache received Potters• 5 people received placebo

• 4 out of 5 with Potters got better

• 2 out of 5 with placebo got better

Critical Appraisal Skills Programmemaking sense of evidence

Typical CASP workshop format

• 1/2 day workshops• Structure

• Introductory talk

• Small group work

• Plenary discussion

• Problem-based, using real papers on, e.g.

• Randomised controlled trials

• Systematic reviews

• Evaluations of diagnostic tests

• Economic evaluations

• Qualitative studies

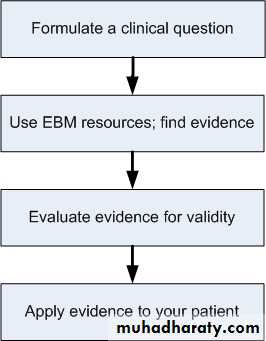

five basic steps for practicing EBM:

• Convert information needs into answerable questions.• Track down with maximum efficiency the best evidence with which to answer them.

• Critically appraise the evidence for its validity and usefulness.

• Apply the results of this appraisal in clinical practice.

• Evaluate your performance.

1. Start with the patient -- a clinical problem or question arises out of the care of the patient

2. Construct a well built clinical question derived from the case

3. Select the appropriate resource(s) and conduct a search

4. Appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and applicability (usefulness in clinical practice)

5. Return to the patient -- integrate that evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences and apply it to practice Self-evaluation

6. Evaluate your performance with this patient

The Steps in the EBM Process

The first step in applying EBM is to develop a clear idea of what type of information you are seeking

Below, a stepwise process named "PICO" is described, developed by faculty at McMaster University which has used problem-based learning and evidence-based medicine in their graduate medical curriculum for more than twenty years.

P Patient population – For which group do you need information?

EXAMPLE: Post-Menopausal WomenI Intervention (or Exposure) – What medical event do you need to study the effect of?

EXAMPLE: Estrogen Replacement Therapy

C Comparison - What is the evidence that the proposed intervention produces better or worse results than no intervention, or a different type of intervention?

EXAMPLE: No Estrogen Replacement

O Outcomes - What is the effect of the intervention? EXAMPLE: Effect on Incidence of Osteoporosis and Breast or Endometrial Cancer

The next step in EBM is to efficiently locate potentially useful information to evaluate and apply to your patient.

The library provides access to several databases and search filters to

expedite your search including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Best Evidence, MEDLINE, PubMed, MD-Consult and access to HSTAT via the National Library of Medicine.

More than twenty years after its conception, ‘evidence-based medicine’ (EBM) continues to invoke polarised debate. There are several areas of disagreement between EBM supporters and detractors as well as unanswered questions about

the role of EBM in modern healthcare.

Proponents

suggest that the goal of EBM is to rescue medicine from many of its major ills, including wide variations in clinical practice, use of unproven interventions, and failure to apply consistent practice guidelines.

Opponents

disagree that EBM adequately addresses these issues, and dismiss EBM

on the grounds of philosophical and practical flaws.

This editorial briefly summarises the criticisms of

EBM under five main themes,

Criticisms of Evidence–Based Medicine

The first type of criticismEBM elevates experimental evidence to primary importance over pathophysiological and other forms of knowledge,

In fact, the preferred situation is for ‘‘clinical trials to provide evidence in support of theory’.’

The second theme

is that the definition of evidence within EBM is narrow and excludes information important to clinicians. EBM grades evidence according to the methods used to collect it. However, randomised trials and meta-analysis have not been found to be more reliable than other research methods.EBM is not ‘evidence-based’ because it does not meet its own empirical tests for efficacy.

Considering that EBM proposes that patient care can be improved by basing clinical decision-making on information from statistically valid clinical trials,

it is somewhat ironic to find there is no evidence (as defined by EBM) that this is actually the case.

Third

the usefulness of applying EBM to individual patients is limited. Because individual circumstances and values vary, and because there are so many uncommon diseases and variants,

For ‘‘an increasing number of subgroups of patients we will never have higher levels of evidence’’. Clinicians must balance general rules, empirical data, theory, principles, and patient values and apply them to individual people. This requires agreat deal of clinical judgment.

Fourth

EBM has been criticised for reducing the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship by limiting the patient’s right to choose what is best in their individual circumstances.EBM could be used as a cost-cutting tool to deny treatment where interventions are not ‘proven’ effective.

On the other hand, EBM could also increase costs by

‘proving’ the efficacy of some expensive interventions.

Currently, the net effect of EBM is unknown.

Lastly

• The five criticisms described above suggest that while EBM can be a useful tool, it has drawbacks when used in isolation in individual patient care.• Modern medicine must strive to balance a complex set of priorities. To be an effective aid in achieving this balance

• theory and practice of EBM must expand to include

• new methods of study design and knowledge integration, and must adapt to the needs of both patients and healthcare professionals in order to provide the best care at the lowest possible cost.

Like any technology, evidence based medicine carries risks and benefits and can be used appropriately or inappropriately.

Overly inclusive definitions threaten to deprive the term of meaning, and unchecked use increases the risk of misuse.

In the past decade, evidence based medicine has contributed much to how we teach, deliver, and think about clinical services. In the coming decade, we must continue to ensure that it is not only used widely but wisely.

Centre for Evidence-Based MedicineUniversity of Oxford

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) was founded in 1994 by

Professor David Sackett and is based at Oxford University.The CEBM is increasingly internationally recognised as the leading organisation

in the field of Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC).

The function of the CEBM is to improve understanding of how and when

health professionals need knowledge, and to assess and develop methods

whereby knowledge, based on current best evidence, can meet that need.

The CEBM actively collaborates with, and assists in, the development of

other Evidence-Based Health Care training programmes internationally, and

currently has more than 350 members in more than 40 countries worldwide.

The CEBM also plays a key international role in developing methodologies

to enable academically validated appraisal of medical information through

the development and provision of critical appraisal tools (both paper and

computer based) and is developing methods to enable sharing of this

appraised knowledge in clinical settings. These methodologies will use the

principles of EBM to help clinicians and health care providers meet their

objectives in improving health care.

Evidence-Based Medicine

In the 1990s, evidence-based medicine emerged as a way to improve and evaluate patient care. It involves combining the best research evidence with the patient’s values to make decisions about medical careLooking at all available medical studies and literature that pertain to an individual patient or a group of patients helps doctors to properly diagnose illnesses, to choose the best testing plan, and to select the best treatments and methods of disease prevention. Using evidence based medicine techniques for large groups of patients with the same illness, doctors can develop practice guidelines for evaluation and treatment of particular conditions. In addition to improving treatment, such guidelines can help individual physicians and institutions measure their performance and identify areas for further study and improvement.

LOOKING FOR EVIDENCE IN THE MEDICAL LITERATURE

Systematic reviews of the medical literature, large randomized controlled trials (the bestway to assess the efficacy of a treatment), and large prospective studies (followed upover time) are types of research published in the medical literature that can be helpful in

providing evidence about tests and treatments. Reports of the experiences of individual patients or small groups usually provide less reliable evidence, although they may

provide important clues about possible adverse effects of treatments.

USING EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE

Practice guidelines developed using evidence-based medicine have helped to reduce mortality (chance of dying) from heart attacks. Evidence-based medicine guidelines have also improved care for persons with diabetes and other common medical problems.Evidence-based medicine does not replace physicians’ judgment based on clinical experience. Any recommendations taken from evidence-based medicine must be applied by a physician to the unique situation of an individual patient. Sometimes there is no reliable research evidence to guide decision making, and some conditions are rare enough that there is no way to do large studies.

IMPROVING YOUR HEALTH

Many evidence-based medicine guidelines are publicly accessible. You can use these guidelines to improve your health and make good choices about your medical care.Together, you and your doctor can make the best evaluation and treatment plans based on the available medical evidence.

Understanding why your doctor recommends certain tests or treatments based on evidence from the medical literature will help you make good health care and lifestyle choices.

Preamble

It is important that the medical profession play a significantrole in critically evaluating the use of diagnostic procedures

and therapies as they are introduced and tested in the

detection, management, or prevention of disease states.

Rigorous and expert analysis of the available data documenting

the absolute and relative benefits and risks of those procedures

and therapies can produce helpful guidelines that

improve the effectiveness of care, optimize patient outcomes,

and favorably affect the overall cost of care by focusing

resources on the most effective strategies.

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) Foundation

and the American Heart Association (AHA) have jointly

engaged in the production of such guidelines in the area of

cardiovascular disease since 1980.

The ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines, whose charge is to develop, update, or revise practice guidelines for important cardiovascular diseases and procedures, directs this effort.

Writing committees are charged with the task of performing an assessment of the evidence and acting as an independent group of authors to develop, update, or revise written recommendations

for clinical practice. The ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines makes every effort to avoid any actual, potential, or perceived arise as a result of an industry relationship or personal interest of the writing committee

Definition of the Problem

A. Purpose of These GuidelinesThese guidelines are intended for physicians and nonphysician

caregivers who are involved in the preoperative, operative,

and postoperative care of patients undergoing noncardiac

surgery. They provide a framework for considering cardiac

risk of noncardiac surgery in a variety of patient and surgical

situations. The writing committee that prepared these guidelines

strove to incorporate what is currently known about

perioperative risk and how this knowledge can be used in the

individual patient.

The tables and algorithms provide quick references for

decision making. The purpose of preoperative evaluation

is not to give medical clearance but rather to perform an

evaluation of the patient’s current medical status; make

recommendations concerning the evaluation, management,

and risk of cardiac problems over the entire perioperative

period; and provide a clinical risk profile that the patient,

primary physician and nonphysician caregivers, anesthesiologist,

and surgeon can use in making treatment decisions that

may influence short- and long-term cardiac outcomes.

B. Methodology and Evidence

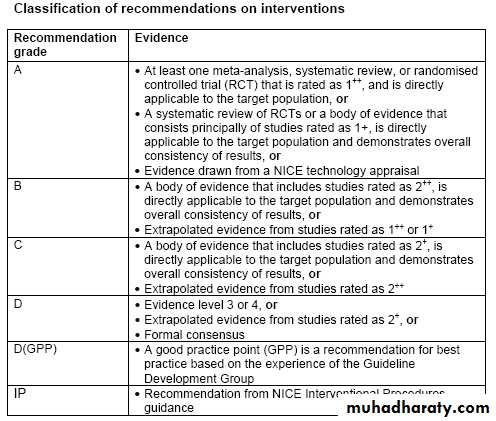

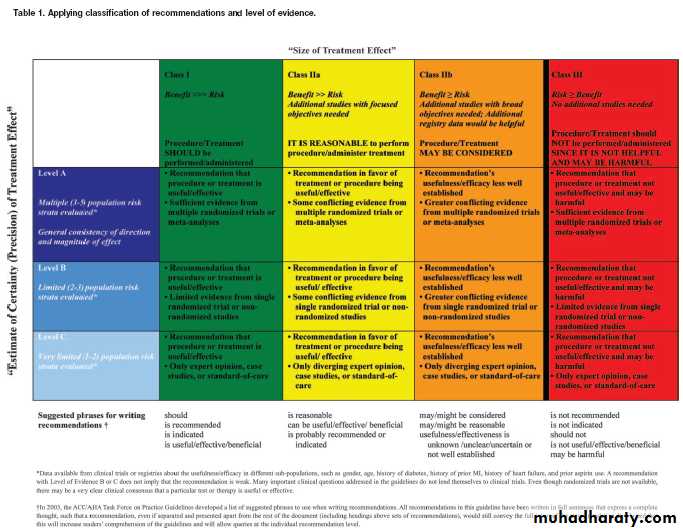

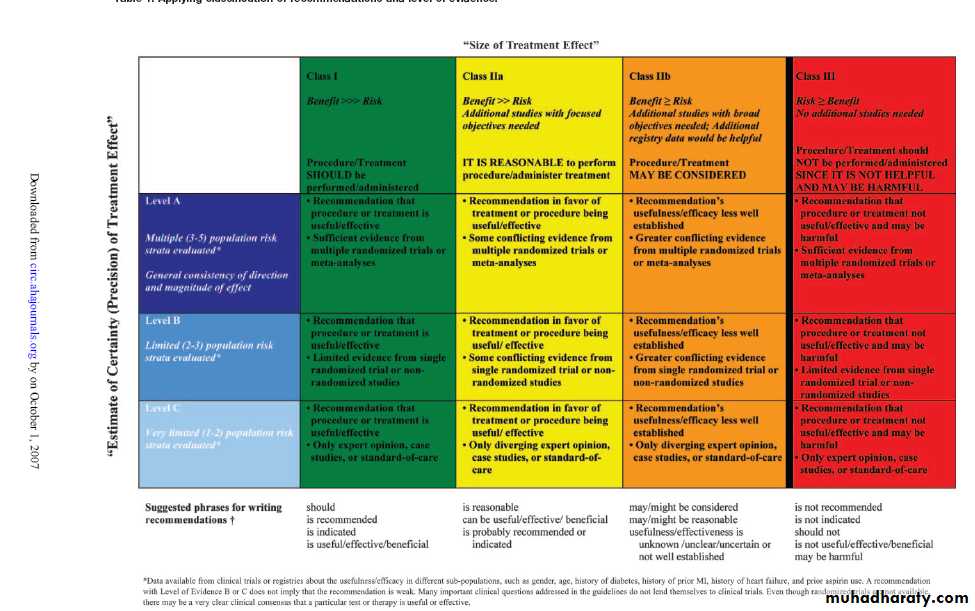

All of the recommendations in this guideline update were converted from the tabular format used in the 2002 guidelines to a listing of recommendations that has been written in full sentences to express a complete thought, such that a recommendation, even if separated and presented apart from the rest of the document, would still convey the full intent of the recommendation. It is hoped that this will increase the reader’s comprehension of the guidelines. Also, the level of evidence, either an A, B, or C, for each recommendation is now providedGrading scheme

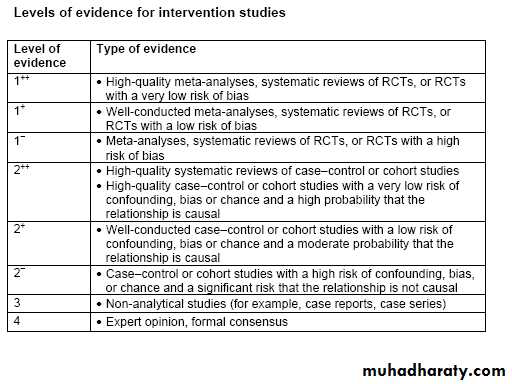

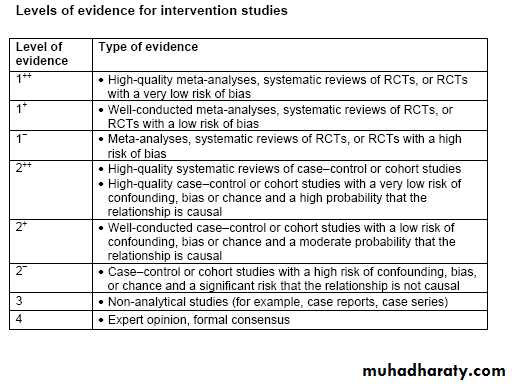

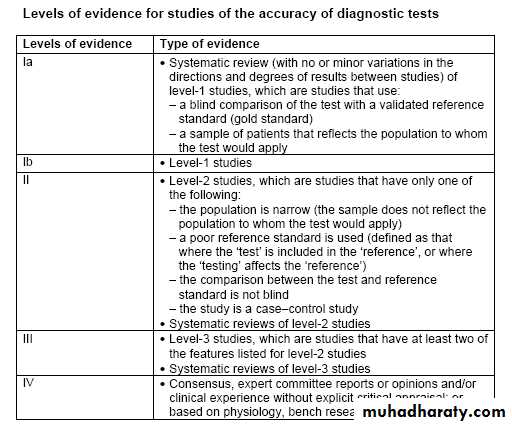

The classification of recommendations and the levels of evidence for intervention studies used in this guideline are adapted from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (‘SIGN 50: a guideline developers’ handbook’),The classification of recommendations and levels of evidence for the accuracy of diagnostic tests are adapted from ‘The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence’ (2001) and the ‘Centre for Reviews and Dissemination report No. 4’ (2001).

الضبابعلمني الضباب ان الانسانقد يمر بلحظات عصيبةومصائب وأزماتلكن لابد أن ياتي الفرج من اللهويعود كل شي كما كان