Childhood cough

BMJ 6 March 2012د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Children often present with cough, and over the counter cough remedies are among the most common drugs given to children, despite lack of evidence to support their use. Questionnaire based surveys of parents suggest that the prevalence of persistent cough in the absence of wheeze in children is high and ranges from 5% to 10% at any one time.

Cough is an important physiological protective reflex that clears airways of secretions

or aspirated material. As a symptom it is non-specific, and many of the potential causes in children are different from those in adults.Chronic cough in a child may generate parental anxiety and disrupt other family members’ sleep. Lessons at school may also be disturbed. For children themselves persistent coughing may be distressing and may affect their ability to sleep, study, or exercise. Parents’ reports of the frequency, duration, or intensity of coughing correlate poorly with objective observations, and reported severity seems to relate most closely

to the impact of coughing on parents or teachers.

Acute cough is typically defined as being of less than three weeks’ duration and chronic cough is variably defined as lasting from three to 12 weeks. Most children with acute cough have a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract, which is self

limiting. Children with an atypical history, or with chronic cough, may be more challenging to assess and are commonly incorrectly diagnosed—with asthma for example—and inappropriately treated.

Despite the wide differential diagnosis for a presenting symptom of cough in children, it is

important to identify its cause and provide appropriate treatment.

We review evidence from systematic reviews and guidelines to present an overview of the causes of cough in childhood and approaches to its investigation and management, highlighting

key factors that should prompt specialist referral.

What is the approach to assessing a child with acute cough?

Consider the potential causes of acute coughBy far the most common cause of acute cough in children is aviral infection of the upper respiratory tract that will need no specific clinical investigations.6 Healthy children cough on adaily basis and experience upper respiratory tract infections several times a year. A systematic review of studies set in primary care found that 24% of preschool children continue to be symptomatic two weeks after the onset of an upper respiratory tract infection.

A child with an acute upper respiratory tract infection will characteristically have a runny nose and sneezing.

A prospective cohort study of non-asthmatic preschool children presenting to primary care with acute cough investigated factors that predict future complications—defined as any new symptom,

sign, or diagnosis identified by a primary care clinician at aparent initiated reconsultation or hospital admission before resolution of the cough.

With a 10% pretest probability, fever,tachypnoea, or chest signs were features most likely to predict

future complications.

However, acute cough may also be associated with a clinically important lower respiratory tract infection, allergy, or an inhaled foreign body, or it may rarely be the presenting symptom of aserious underlying disorder, such as cystic fibrosis or a primary immunodeficiency.

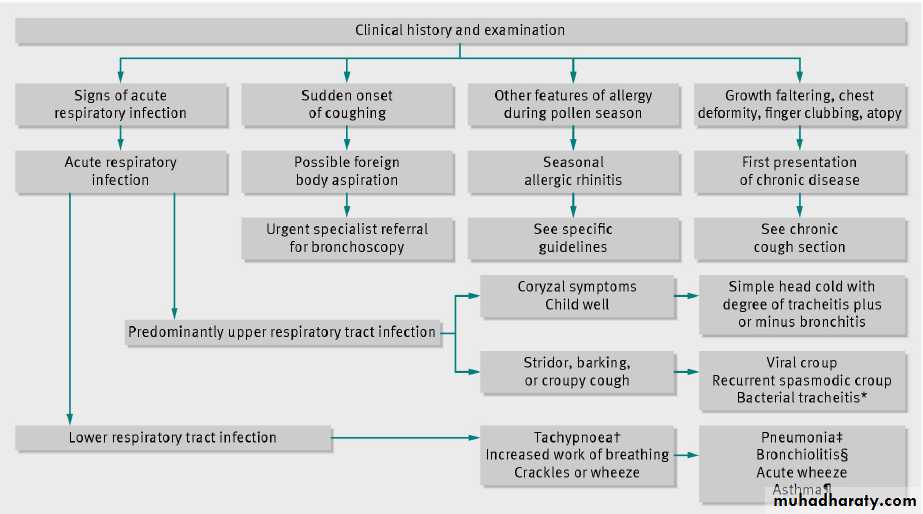

Take a careful history and perform a thorough

clinical examinationThe figure⇓ describes factors in the history and examination that point towards a specific diagnosis in a child with acute cough. Urgent referral for specialist assessment and rigid bronchoscopy is indicated if an inhaled foreign body is suspected. Foreign body aspiration is not always accompanied by an obvious history; suggestive features include sudden onset

of coughing or breathlessness.

Include in the clinical examination an initial rapid assessment to judge the child’s general condition, incorporating objective measurements of respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturations,

and temperature. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has published guidance on the assessment of feverish illness in preschool children. Promptly refer any child who is acutely unwell to specialist paediatric services.

Examine for signs of an upper respiratory tract infection (for example, runny nose, inflamed tympanic membranes, and throat) or effects on

the lower respiratory tract (for example, crackles, wheeze, or abnormal air entry). Systematic reviews have shown that the best single finding to rule out pneumonia is the absence of tachypnoea.

Parental concern and the clinician’s instinct that something is wrong remain important red flags for serious illness in settings with a low prevalence of serious infection.

Exclude the presence of any signs of a more chronic problem, such as poor growth or nutrition, finger clubbing, chest deformity, or atopy.

Pertussis is a cause of acute and chronic cough in children and is discussed further in the chronic cough section. In the acute setting be aware of the potential for severe disease in young and high risk infants, where it may be associated with apnoea and

systemic illness.

When to consider specialist referral and

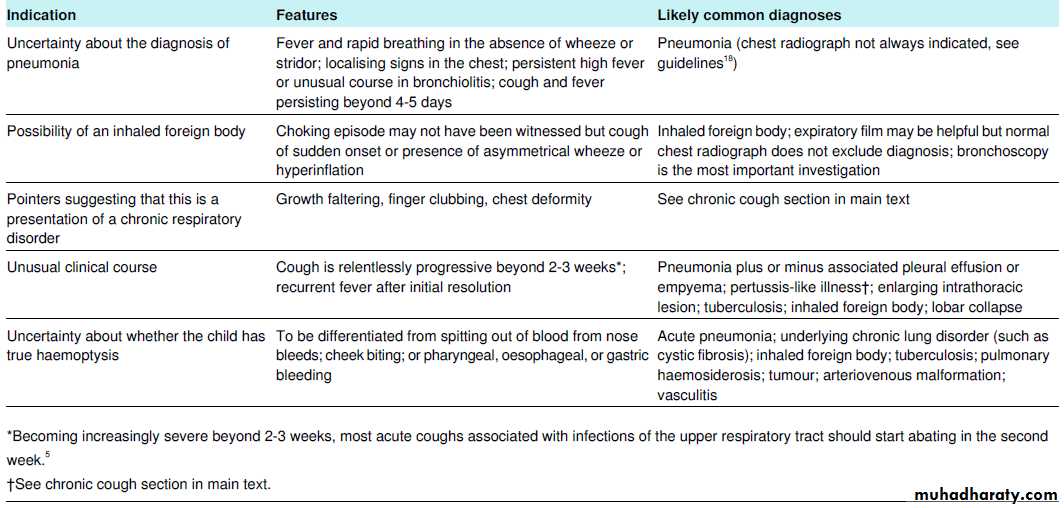

further investigationTable 1⇓ summarises indications for performing chest

radiography and considering specialist referral. Referral is especially appropriate when acute cough is progressive and severe beyond two to three weeks; if there are signs suggestive of a serious lower respiratory tract infection; if haemoptysis is present; or if the clinician suspects underlying pathology, such as cancer, tuberculosis, or an inhaled foreign body.

How can acute cough be managed?

Supportive treatment only, including antipyretics as necessary and adequate intake of fluids, is indicated for viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. Antibiotics are not beneficial in the absence of signs of pneumonia, and bronchodilators are not effective for acute cough in children who do not have asthma.Cochrane review found no good evidence of effectiveness of over the counter drugs for acute cough, such as antihistamine or decongestant based preparations. Young children have died from an overdose of over the counter drugs for cough, and

in the United Kingdom such drugs have been withdrawn for children under 6 years.

If pertussis is diagnosed, treatment with a macrolide antibiotic is indicated. Unless the diagnosis is established in the first two weeks of infection, which is clinically unlikely, the main role of these drugs is to reduce the period of infectivity. There is currently no evidence to support the use of bronchodilators,

steroids, or antihistamines in acute pertussis.

Future unnecessary healthcare consultations may be reduced by explaining these points to parents, carefully exploring their worries, and providing them with information about what to expect. Precautionary advice about appropriate re-consultation if symptoms progress or do not improve is equally important.

Acute cough associated with hay fever during the pollen season may be successfully treated with antihistamines or intranasal steroids. Evidence based guidelines exist for the management of community acquired pneumonia,18 bronchiolitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis in children.

What is the approach to assessing a child

with chronic cough?In the short to medium term most coughing in children relates to transient respiratory tract infections that will settle by three to four weeks. British Thoracic Society guidelines define chronic cough as cough that lasts longer than eight weeks, with the stated caveat of a grey area of prolonged acute cough or subacute cough in children with pertussis or postviral cough

that takes three to eight weeks to resolve.

A prospective cohort study of school aged children presenting to primary care with

a cough lasting 14 days or more found that around a third had serological evidence of recent Bordetella pertussis infection, and nearly 90% of these children had been fully immunised.Consider the type of chronic cough

Children with chronic cough may be divided into threegroups—normal children; children with specific cough and aclearly identifiable cause; and children with so called non-specific isolated cough, who are well with a persistent dry cough, no other respiratory symptoms or signs of an underlying disorder, and a normal chest radiograph.

Non-specific isolated cough is a label rather than a diagnosis, and such children need to be kept under careful review. Children in this group have

an increased frequency and severity of cough, although the specific cause has not been identified. If no specific cause can be found for the chronic cough, plan a follow-up visit to allow re-evaluation and assessment at a later date. Non-organic coughing includes habit cough and psychogenic cough.

Recurrent cough refers to more than two protracted episodes of coughing a year that are not associated with a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract.

History and examination

A careful history and examination will enable the clinician to identify features that may be suggestive of an important underlying disease process that requires specialist opinion or targeted intervention.

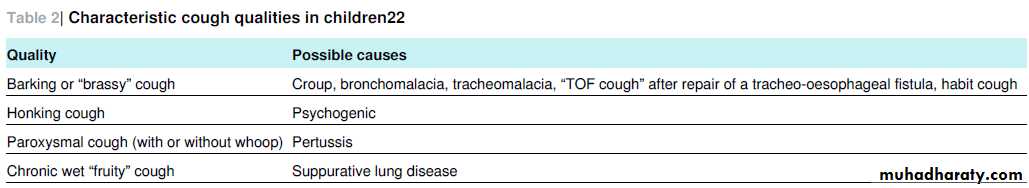

Box 1 lists points to consider when taking a history. It is vital to clarify what the child or parent means by cough. Some causes produce a characteristic cough, and it is important to hear the cough because parents’ reports of respiratory symptoms such

as wheeze, stridor, and nocturnal cough may not be accurate.

Table 2⇓ presents specific types of cough.

Most young children do not expectorate sputum so it is important to determine the

nature of the cough—wet or dry. Ask parents if they have observed phlegm in the child’s vomitus. If the cough is episodic and cannot be heard at the time of consultation ask the parent to try to bring the child in during an episode.Ask about environmental factors that may contribute to cough, particularly exposure to tobacco smoke or allergens. Consider and carefully ask about psychological problems, and explore parents’ concerns

and expectations.

A thorough general examination should look for signs of atopy and clubbing of the fingers. Plot a growth chart and check whether the child’s growth rate has recently slowed. When the child coughs feel the chest for palpable vibration owing to partial airway obstruction by retained secretions.

Note any chest deformity suggestive of a chronic problem, such as increased anteroposterior diameter, sternal bowing, pectus carinatum, or

Harrison’s sulcus above the costal margins. Auscultate the chest listening for the quality, nature, and symmetry of air entry along with any added crackles, wheeze, or rubs. Listen for upper

airway sounds and perform an ear, nose, and throat examination, particularly looking for signs of allergic rhinitis, including nasal polyps.

When should further investigation and referral

be considered?Systematic reviews and guidelines point to several red flags that should prompt swift referral to specialist care for investigation (box 2). In particular, the presence of a chronic wet cough is abnormal and should trigger referral for investigation of chronic suppurative lung disease.

In 2007 screening was introduced for cystic fibrosis in the UK as part of the newborn bloodspot programme. This programme will not detect every child with cystic fibrosis and some will still present clinically with chronic respiratory symptoms, malabsorption, or growth faltering.

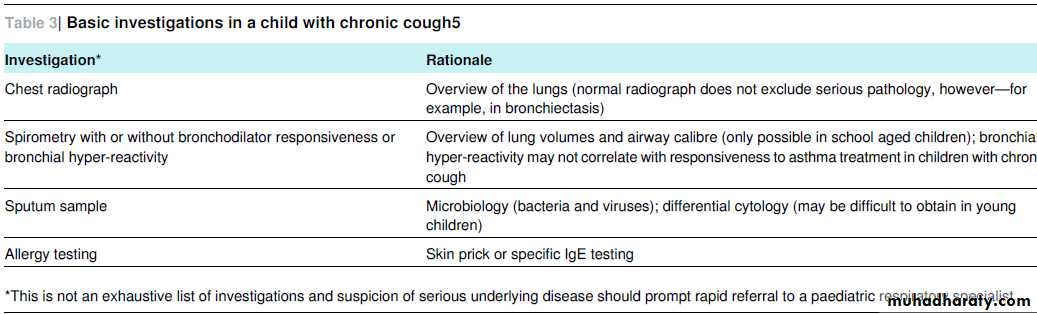

Table 3⇓ outlines basic investigations to be considered in a child with a chronic cough.

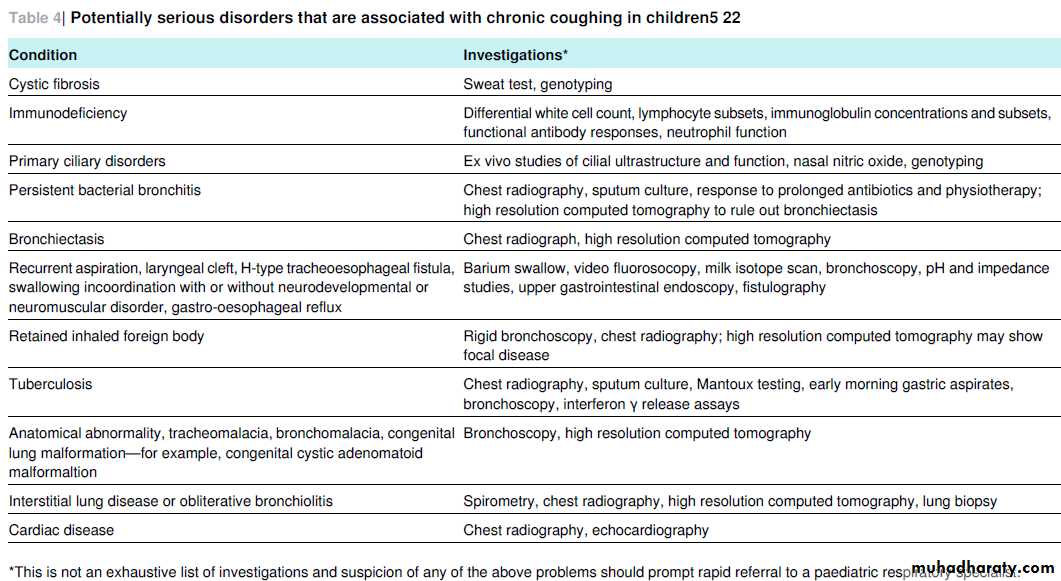

Table 4⇓ briefly outlines some of the potentially serious lung conditions associated with chronic coughing and the investigations performed in secondary or tertiary care that may uncover them. Persistent bacterial bronchitis in children is increasingly recognised. Such children have a chronic productive wet cough but the diagnosis can be

made only after underlying causes (table 4) have been excluded and a positive sputum culture result.

Do children with isolated chronic cough

have asthma?Subsequent prospective studies have supported the opinion expressed in 1994 by McKenzie that—in the absence of wheeze or dyspnoea—very few children with non-specific isolated cough have asthma. Only a small proportion of children with non-specific isolated cough have eosinophilic airway inflammation. Bronchial hyper-reactivity is associated with wheeze but not with isolated dry or nocturnal cough. Children

with a recurrent dry cough may, however, have genuinely increased cough sensitivity.

If clinical features—such as wheeze, atopy, or a strong family history—suggest that the child has asthma, consider a trial of an inhaled corticosteroid as anti-asthma treatment. Ensure the effective delivery of appropriate doses of drug, as advised by evidence based asthma management guidelines—for example, in a 6 year old child 100 μg of beclometasone dipropionate delivered twice daily via a spacer device. Clearly define outcomes that will be recorded over a set period, such as a

symptom and peak flow diary recorded over 8-12 weeks. After the trial stop the treatment to allow assessment of its effect.

If the child can perform spirometry or peak flow measurements, BTS asthma guidelines recommend an assessment of the reversibility of airway obstruction in response to an inhaled bronchodilator. Asthma is unusual in children under 2 years of age. The clinical diagnosis of asthma in children is often challenging, and specialist referral is appropriate if there is

uncertainty or symptoms are difficult to control.

Is gastro-oesophageal reflux a cause of

chronic cough in children?The association between gastro-oesophageal reflux and

non-specific isolated cough in children has not been fully

elucidated. In otherwise healthy children there is little evidence to suggest that gastro-oesophageal reflux alone is a cause of cough. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is common in infancy and is only sometimes associated with cough. An empirical trial of drugs for reflux in children with non-specific isolated cough is not currently recommended because evidence of their efficacy

is lacking.

How can psychogenic cough be recognised?

Many clinicians will be familiar with the phenomenon of a dry repetitive habit cough that persists for some time after an upper respiratory tract infection has cleared. Psychogenic cough may be disruptive, bizarre, and honking, with no organic cause in an otherwise well child. Characteristically, psychogenic cough is less prominent at night or when the child is distracted and more

prominent in the presence of carers or teachers. The habit may be reinforced by secondary gain derived, such as time off school. Consider Tourette’s syndrome or other tic disorders, particularly if features other than an isolated cough are present.

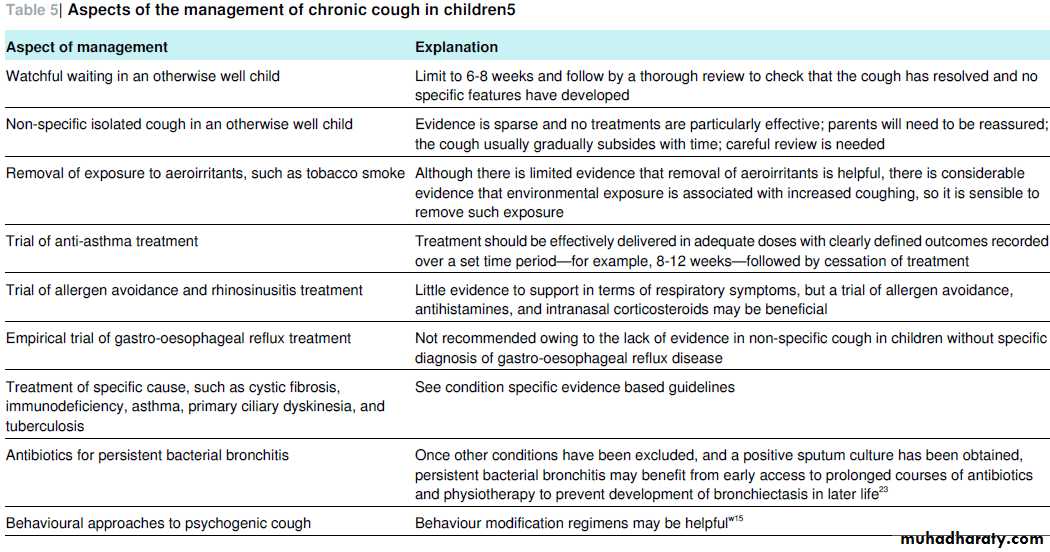

An approach to managing a child with chronic cough

Appropriate management of chronic cough in children depends on reaching an accurate diagnosis that allows targeted treatment.Treatment algorithms used for chronic cough in adults are not useful in children because the three main causes of chronic cough in adults—cough variant asthma, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and postnasal drip—are rarely relevant in children. Table 5⇓ outlines specific considerations in the management of chronic

cough in children as recommended by BTS guidelines.

Summary points

Acute cough usually resolves within three to four weeks, whereas chronic cough persists for longer than eight weeksMost cases of acute cough in otherwise normal children are associated with a self limiting viral infection of the upper respiratory tract Cough is a non-specific symptom, and in children the differential diagnosis is wide; however, careful systematic clinical evaluation will usually lead to an accurate diagnosis It is crucial to hear the cough because parents’ reports of the nature, frequency, and duration of coughing are often unreliable Isolated cough without wheeze or breathlessness is rarely caused by asthma Adult cough algorithms are not useful when assessing children.

Box 1 Important points in the history of a child with chronic cough

Nature of the cough:• Severity

• Time course

• Diurnal variability

• Sputum production

• Associated wheeze

• Disappears during sleep?

• Any haemoptysis?

Age of onset

Relation to feeding and swallowing (is there a problem with aspiration?)

Fever

Contact with tuberculosis or HIV

Chronic ear or nose symptoms (is there a problem with cilia function?)

Foreign body aspiration

Relieving factors, such as bronchodilators or antibiotics

Exposure to cigarette smoke

Possible allergies and triggers

Immunisation status

Use of drugs, such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

Family history of atopy (is this asthma?) or chronic respiratory disorders

General growth and development

Box 2 Red flag features that should prompt specialist referral

Neonatal onset of the coughChronic moist, wet, or productive cough

Cough started and persisted after a choking episode

Cough occurs during or after feeding

Neurodevelopmental problems also present

Auscultatory findings

Chest wall deformity

Haemoptysis

Recurrent pneumonia

Growth faltering

Finger clubbing

General ill health or comorbidities, such as cardiac disease or immunodeficiency

Tips for non-specialists

Most episodes of acute cough in children are related to self limiting viral upper respiratory tract infections

In most cases, a diagnosis can be made by taking a careful history, exploring parental concerns and expectations, and conducting asystematic examination.

In a child with acute cough, signs of respiratory compromise, suggestion of foreign body aspiration or serious underlying disease should prompt swift referral to a specialist .In children with chronic cough, quickly refer those with faltering growth, neurodevelopmental abnormalities, wet productive cough, or other signs of underlying disease.

Most children with a non-specific isolated cough will improve with time.

Unanswered questions and areas for future research

Acute and chronic cough are common conditions in childhood; what is the real impact of cough on children, families, and society?Evidence from good quality research studies is needed to inform the management of cough in children

What factors accurately predict the causes and natural course of acute and chronic cough in children?

Factors that point towards a specific diagnosis in a child with acute cough. *Bacterial tracheitis is a rare but life threatening condition (croupy cough helps distinguish it from epiglottitis) that is associated with a high fever and progressive upper airway obstruction; it requires prompt specialist care—normally securing of the airway and intravenous antibiotics against

Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae B, and streptococci.