Obesity

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

06/17/2010

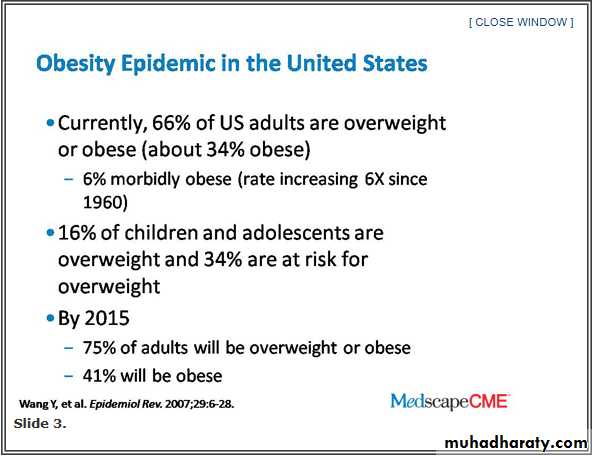

Dr. Fujioka: I would like to start off the discussion looking at the global problem, the epidemiology of the consequences of obesity, obviously in the world but also in the United States. This is hard to imagine, but I think you all know this. Roughly 66% of US adults are either overweight or obese. The sad part is, of that percentage, roughly one third of Americans are clinically obese. What that means is that they are not going to live a full life, and because of their weight their lifespan is shortened. [Another group] to note is the morbidly obese, that is, somebody who is 2 times normal weight. That is now 6% of the US population.

The fat cells begin to make what we call adipokines or proteins that really are not nice proteins. They are really inflammatory factors, such as TNF-alpha [tumor necrosis factor-alpha], interleukin-6, and chemoattractant proteins, which are really nasty proteins. As patients become overweight and obese, they are in this chronic inflammatory state.

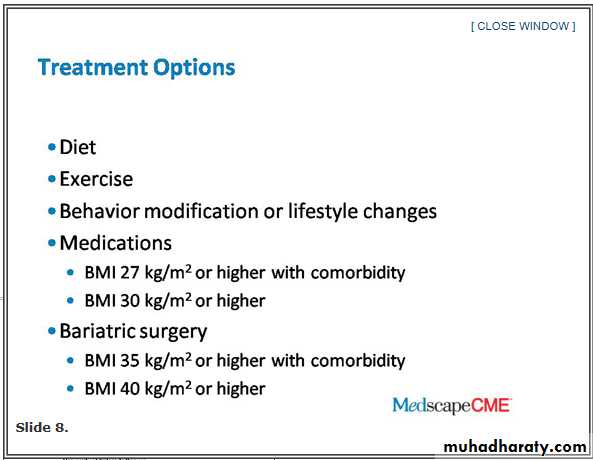

Dr. Fujioka: Well, what are we going to do now? You have got diet; you have got exercise; you have got behavioral modification or lifestyle modification; and it is not like somebody has a psychological problem. You are just trying to change their behavior. Then we get into medications.

For somebody with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher with a comorbid problem or a BMI of 30 kg/m2 with none, their options should include medications and then bariatric surgery, which again sounds drastic, but there are 2, 3, or 4 different types of surgeries all coming down the pipe that are working pretty well. You need to at least keep this in the back of your mind. Again, these are for the morbidly obese patients who are roughly twice their normal weight.

Dr. Hill: Let me start out by making a couple of points. One is just about our entire population is gaining weight. Everybody is gaining weight, and you can see here in the bottom of the slide that you have the body mass index distribution from the late 1970s to 2000.[7] You can see it is shifted to the right, which means that the people who were heavier are gaining weight, and the people who were leaner are gaining weight. The whole population is gaining weight. In fact, the average American gains 1-2 lb a year. Who notices, right? But over a decade, it is an extra 10 or 20 lb, so we are a population gaining weight.

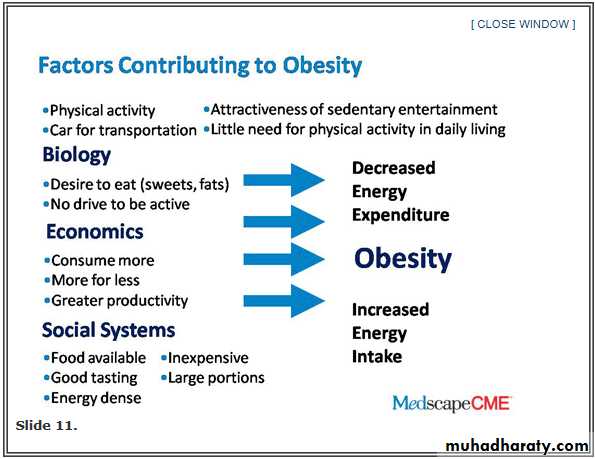

The second point is that weight gain is probably due to very small differences between the energy we take in and the energy we expend. if you take in the same number of calories that your body burns, you are going to be weight stable. To explain this gradual weight gain, it means that over time we are taking in more calories than we expend. What is causing that? What are the factors that cause us to eat more and to expend less energy? Those are substantial.

Our biology is pretty permissive of weight gain. Most of us are happy to be sedentary when we don't have to be active, right? We sit around all day and we are happy with that. Most of us are happy to eat whenever food is available. If you think about it, lots of people eat not because they are hungry but because there is food available, and there is food available all the time.

Your biology is saying rest and eat, and it is possible to rest and eat most of the time now. Economics plays a role. That is where supersizing came from: more for less. Americans love more for less.

Supersize those french fries! So economics is playing a role in larger portion size. Now there are some exciting new data to suggest that we are influenced by the people around us, our social systems. You are influenced by those people you hang out with. If they are out for pizza and beer every night, you are out for pizza and beer and the whole gang is gaining weight.

You have these 3 powerful forces:

biology, economics, and social systems. What they have done is that they have led us to create an environment where we can rest and eat all the time. Think about it. Very few of us have to be physically active during the day.

We go from the bed to the elevator to the chair at work and then back home and watching TV at night. We have this very, very sedentary population. We have created a food environment where there is food everywhere. It tastes great. We have asked the food industry to make food taste great. We asked them to make food very inexpensive and easily accessible. We have access to food and we don't have to work very hard during the day, so we have created this environment that in a way is facilitating obesity.

You have all these powerful forces that tend to make us eat more and to be less physically active. Despite that, we are only gaining 1-2 lb a year. I think what we are seeing is that the body's own balance system is trying to oppose this environment and these behaviors, but at the end of the day we are gradually in this positive weight-gain scenario where we are gaining 1-2 lb every year and people are still gaining weight.

We have estimated that if you could modify your patients' energy balance, that means either their intake or their physical activity, by only 100 calories a day you could stop weight gain in most of your patients.

A hundred calories is nothing.

A 12-oz soda is 150 calories.

A hundred calories is 10 or 15 minutes of walking.

It is possible to stop weight gain with small changes. Now if you want to take people who are already obese and have them lose weight, it is going to take greater lifestyle changes. There are 2 components to treating obesity. One is getting the weight off. We are actually not very bad at that. We can produce weight loss. The second is preventing weight regain. Most people who lose weight regain that over a period of 5 years or so.

We have looked at this question of how much behavior change you need to lose weight and keep it off. If your goal in your patients is to have them make those lifestyle changes to keep weight off, how much change do they need to make? What happens is as you lose weight your body compensates and your resting metabolic rate decreases. After you have lost weight, your energy requirements go down. What that means is following weight loss you need fewer calories to maintain your weight than before weight loss because you have a smaller body.

We have looked at how much is that? Let's look at a patient who might lose 10% of body weight. We are pretty happy if we get a 10% weight loss. For a 10% weight loss, what you see is an amount of energy that is 150-200 calories a day that has to change, so to keep that weight off they are going to have to eat this many fewer calories or increase physical activity, or do both in combination. It doesn't seem too hard, and, in fact, we are reasonably successful at producing and maintaining a 10% weight loss, but this gives you a sense of the degree of behavior change that you are going to need to achieve that.

A lot of people want more than a 10% weight loss, so what happens if you go to a bigger weight loss? Here you can see if you are going to produce 15% weight loss; now you are talking substantially more behavior change, 250-300 calories a day. It is harder to get that kind of behavior change, but what it gives us is a quantitative goal for how much behavior change we are going to need to be successful. In treating obesity that is substantial -- substantial with a 10% and pretty high with a 15% -- we are not very good at keeping a 15% weight loss off.

Well, we can work harder to change behavior. We have been doing that with very little success. Maybe we are going to get better at doing that. Maybe we understand better the physiology, so we know where to go in and intervene. Maybe it gives us the opportunity for new drugs that work on different physiologic systems to help keep the weight off. This is where there is a lot of promise, so if you are talking about trying to achieve a 300-calorie change, some of that could be with diet, some of that with physical activity, and some of that with a pharmaceutical agent.

You need to use all the tools that you have. Perhaps we are going to learn to change the environment. We haven't done that very well right now, but that is one way that we might go forward. Perhaps we are going to change the culture where people value healthy eating and physical activity, but where we are right now is the degree of behavior change that we need to produce and maintain a 10% or 15% weight loss, which is pretty big. We are not all that successful at doing it. We need new tools, we need to modify behavior, and we need better drugs to treat and prevent obesity.

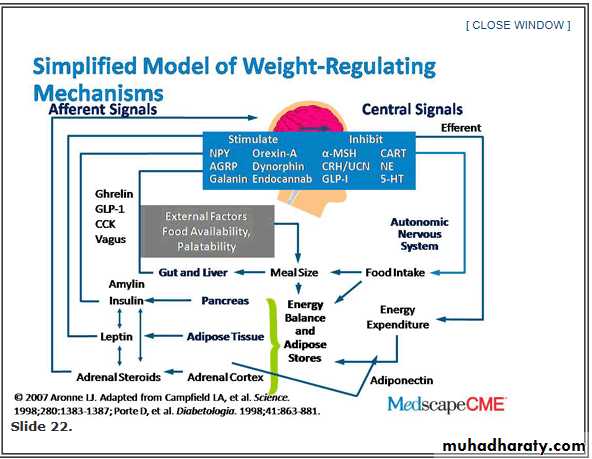

Dr. Apovian:. We have learned about how the prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing, and it is probably due to the environment changing around us. Dr. Hill went over what it is going to take to get people back to a healthier weight, and even though that energy gap is relatively small, at 100-300 calories a day, it is very hard behaviorally to keep people losing weight and keeping it off. We have learned over the past 20 years through research about how the brain regulates appetite and metabolism. There are many mechanisms involved in why people are gaining weight, but really why people can't keep it off.

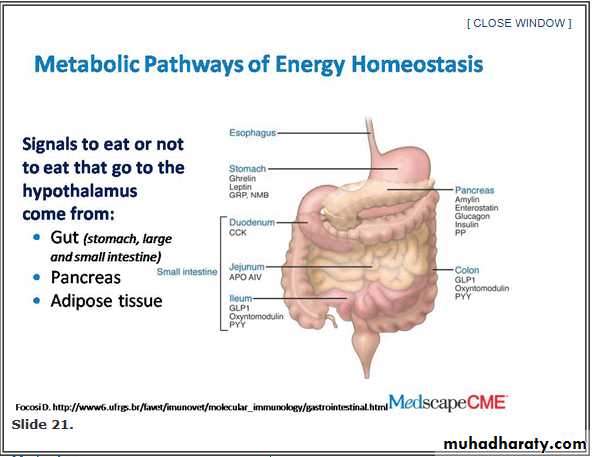

When we look at the brain, the center of appetite and the homeostatic regulation of energy expenditure and appetite are in the hypothalamus. We get signals every day from the gut, the small and large intestine, from the pancreas, and from fat tissue as to whether or not we are full or hungry.

We have learned over the past 20 years that fat cells are actually organs that secrete substances that not only cause inflammation, but also send signals back to the brain as to how much fat stores we have. We think that we have a setpoint of body weight that we try to defend, and we try to defend that body weight by secreting hormones from fat tissue to alert the brain as to how much fat is available.

Dr. Apovian: Why is it hard to lose weight, but more importantly, why is it so hard to keep the weight off? Well, when you have multiple pathways regulating our fat stores, when we try to lose weight what we have learned is that levels of leptin, a hormone that we have all heard about, is secreted from fat tissue. In 1994 we thought we found the cure for obesity because when we injected leptin into mice that were deficient in leptin they lost weight. Big mice lost weight, but in humans it is not so easy because we have leptin resistance.

When we lose weight, we have less fat tissue because we have lost the fat. Less leptin goes back to the brain, and that signals the brain to change the homeostasis so that we are almost forced to regain that fat tissue by increasing our food intake. The brain also decreases our energy expenditure. It is really fascinating because what happens is that we fidget less, and not only does our resting metabolic rate drop, but we also do less physical activity.. So the brain is trying to get us back to what we think is the initial setpoint.

This was based on survival, so a long time ago when we were foraging for food we couldn't starve. If we starved, of course, we died, and so our genes developed so that we protected our fat stores because that meant survival. Unfortunately, the environment has changed. We now have many ways of getting high-calorie foods for very little expense, and so our environment is keeping us at this new higher body weight. What can we do? Dr. Hill talked about changing behavior. It is very difficult.

Current and Emerging Antiobesity Drugs and Drug Combinations

Dr. Apovian: Perhaps another tool that is available is to try to change the mechanisms for appetite, hunger, and satiety by adding a drug to a regimen of diet and physical activity. Let's see what the data have shown.

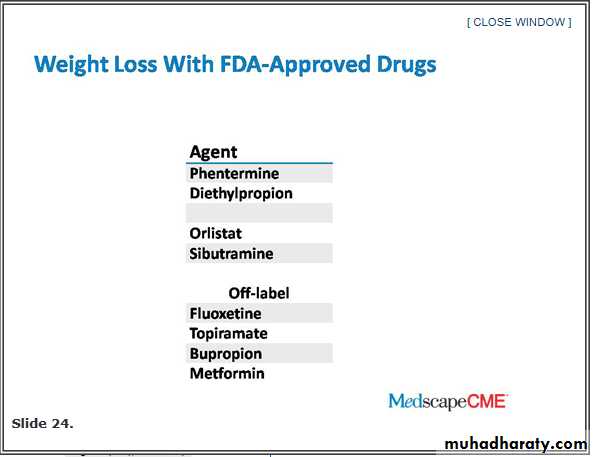

Dr. Apovian: We have several FDA [US Food and Drug Administration]-approved drugs that can help patients lose weight. One that has been approved for quite a while now is phentermine. It has been on the market since the early 1970s. It affects norepinephrine levels in the brain to help induce a state of satiety. It works short term. It was approved by the FDA for only 3 months, but it is still on the market. It is a fairly efficacious agent.

All of these agents can help patients lose up to about 10% of their body weight -- no more than that and at times less than that. These drugs should be considered as adjunct tools to dietary changes and an increase in physical activity. We also have sibutramine, which has been approved since 1998. It works on norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin levels in the brain. Again, just like phentermine it can induce a state of increased satiety. Both of these drugs work on the hypothalamus to induce a state of increased satiety with less food. There are other drugs that have been used off-label to try to help patients lose weight, and I will be talking about those as well.

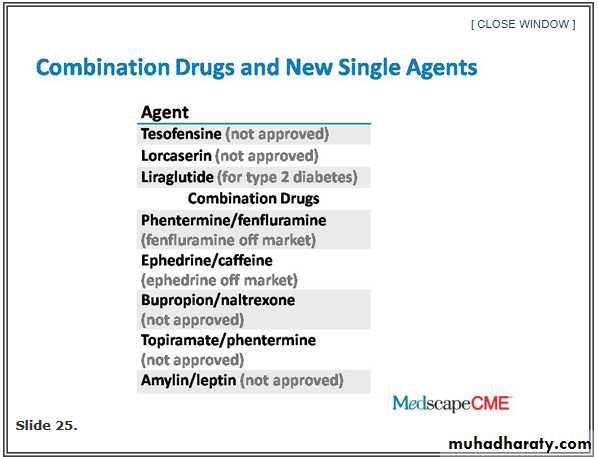

Dr. Apovian: Coming up in the next few months, we have 2 combination agents [under FDA review], and in the future maybe 3 drugs combined to try to synergistically get even more weight loss for our patients. One of these combinations is bupropion and naltrexone. Bupropion is an antidepressant. Naltrexone is an antiaddiction drug that has been used to help patients with drug addiction and alcohol addiction. A company has combined the 2, bupropion and naltrexone, and has shown that this combination can help patients lose a little bit more weight than diet and exercise alone.

Another combination is phentermine, which has been on the market for weight loss for quite a while, plus topiramate, which is an antiseizure drug. In combination, these 2 drugs have been shown to help patients lose a little bit more weight than either drug alone

Dr. Apovian: This is a graph from 1968 when phentermine was studied showing that patients on phentermine, along with diet and exercise, can lose more weight than diet and exercise alone.As you can see, if you take a patient off phentermine, which was done in this trial, patients slowly regained weight.

If you put patients back on the phentermine, they lose the weight again. The moral of the story here is these drugs work if you take them. When you stop taking the medication appetite comes back. That is where your diet, lifestyle change, and [increase in] physical activity have to be continued for an indefinite period of time -- forever -- or you will regain the weight.

Dr. Apovian: you can lose up to 8% of your body weight compared with the placebo group, which got diet and exercise alone, 2.4% or even 1.4%, compared with the group that got the combination. This combination looks very promising if it is FDA approved later on in the year.

• Naltrexone and Bupropion

Dr. Apovian: Another combination is zonisamide, which has been approved as an antiseizure drug, in combination again with the antidepressant bupropion showing a dose-dependent weight loss compared with placebo. This is another combination of 2 drugs that can help patients lose weight.

Dr. Apovian: A study showing that topiramate, the antiseizure drug, in combination with phentermine can help people lose more weight than either topiramate alone or phentermine alone. In this study, the subjects who were on topiramate plus phentermine lost 11.4 kg, which is quite a bit of weight. This was a short-term study, but the company is doing long-term trials as well.

• Phentermine and Topiramate

Dr. Apovian: Lorcaserin is another new agent soon to be looked at by the FDA for approval. It is a 5-HT2C agonist, and it works on that receptor in the brain to help patients feel full with less food.Adose-dependent weight loss that is better than the placebo group, which received diet and exercise alone. Provided that they are approved by the FDA later on this year, we will have more tools in our armamentarium than just phentermine, sibutramine, and orlistat, which is a fat blocker.

• Lorcaserin

Dr. Apovian: Now there are drugs out there that have been approved for other uses that can help patients lose weight, notably the GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) agonist. This is called exenatide, and exenatide was approved a few years ago for type 2 diabetes. It helps patients lower their [glycated] hemoglobin A1c and get their blood sugar under control, but it also helps patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity lose a little bit of weight. We are now using some of these newer agents for diabetes to help them lose weight in addition to lowering their hemoglobin A1c

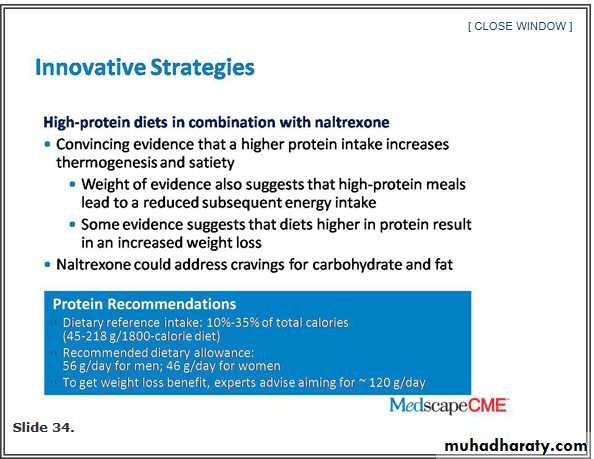

Dr. Apovian: How do we increase satiety, reduce appetite, and address cravings in a multidisciplinary multimodal fashion using hopefully these new drugs? There are many innovative strategies using diet, physical activity, and some of these new tools. Adjusting macronutrient content may be helpful.

• Maintaining Weight Loss

Dr. Apovian: Studies have shown that higher-protein diets can help patients increase satiety because, as a matter of fact, protein and fat seem to be more satiating than carbohydrates. If you increase the macronutrient content of the diet in terms of protein, you can try to help the patient feel more full perhaps with less calories.

Something like naltrexone, if the combination is approved by the FDA, can also address cravings for carbohydrate and fat because naltrexone is an antiaddiction drug, and there are some studies that suggest that if subjects have a craving for carbohydrate and fat, naltrexone in addition to changing the macronutrient content of the diet can help patients feel full and not crave those carbohydrates.

Dr. Apovian: How can we help the body maintain the weight loss? A lot of patients can lose weight, and I have shown you how the body really fights you in terms of lowering those leptin levels, getting the body to gain that weight back.

Dr. Apovian: Leptin may be a key factor here in helping patients keep the weight off. Studies have shown that combining human recombinant leptin, which is not FDA approved yet and still in clinical trials, with weight-loss agents can actually help patients lose a little bit more weight and perhaps maintain that weight loss as long as they continue to be on the drug.

This study shows that the combination of leptin with something like amylin, which is pramlintide -- which was approved for type 2 diabetes -- can help patients lose more weight than amylin or leptin alone.

Dr. Apovian: We are now looking at perhaps triple-combination therapies to not only help people lose weight but keep the weight off with the use of a hormone, such as leptin, which we seem to need replaced. If we lose weight we want to replace that leptin and keep those signals going to the brain to help us continue to feel full at a lower body weight. I think the research is showing that we can actually do that with a weight maintenance hormone like leptin.

Dr. Apovian:

Does it really matter to eat breakfast? Most of my patients who come to see me for weight loss don't eat breakfast. What does breakfast give us? I think it gives us structure so that if we eat meals at various time differences during the day, we are providing ourselves with structure around food.If we can also do that around physical activity, I think we can help patients maintain their weight loss. Many patients eat breakfast every day, and they have managed to keep their weight off. Many weigh themselves at least once a week. What does that do? That makes them aware of how they are doing with their weight-loss goals. Many patients watch less than 10 hours of TV per week, and I mention that because Americans on average watch about 3-4 hours of TV per day, especially our kids..

I think we have to adopt less sedentary activities and more physical activity. If you are a patient and you do all these things, or if you are a PCP (primary care physician) and you help your patient do all these things, I think you have a good chance to help your patient not only lose the weight but keep it off

Dr. Apovian: Of the cardinal behaviors of successful long-term weight management -- in addition to getting the weight off and maybe with some of the tools that I have mentioned -- self-monitoring seems to be very important. Recording food intake daily is one of the tools that we use in our weight management centers to help patients become aware of what they are eating, and then checking body weight once a week on a scale also seems to be very important.

Patients need to be on a low-calorie, low-fat diet.We know probably that they are eating a little bit more than that, and their energy intake from fat is about 20%-25%. A low-fat, low-calorie diet and eating breakfast daily seem to be helping patients keep the weight off, and regular physical activity, about an hour a day, which means walking about 4 miles per day. With that you can expend 2500-3000 calories per week. Again, the tools that I mentioned for weight loss, including adjunctive medications, should be seen as that, adjuncts to a lifestyle change program, diet, and physical activity.

Dr. Apovian: We have just hit the tip of the iceberg with leptin. There are probably many other hormones that help us maintain that homeostatic mechanism, and it is a survival mechanism because after all if we don't eat we starve and we die. We have got to figure out better methods of counteracting these homeostatic mechanisms.

Dr. Apovian: The future would combine many different drugs -- 2, 3, maybe even more drugs -- to help patients keep the weight off. Combining that with a change in their physical activity and their diet and perhaps, in the long-term future, changing our environment back to a healthier environment so that we can maintain these lifestyle changes, would address this challenge that we have [with weight loss and maintenance of weight loss].

Dr. Hill: The diet you will stick with forever because people will go on a diet and they will go off a diet. When you go on a diet you lose weight. When you go off a diet you regain it. The perfect diet is one that you would stay on long term. I tend to think for most people that is probably a diet fairly low in fat, but the physical activity component is important, too. If you want to go on a diet temporarily, you will lose weight temporarily. If you want to permanently change your weight, find a diet that you can stick with forever.

Dr. Fujioka: Jim, put yourself in a primary care physician's office. He has got 10-12 minutes with a patient. Any tips on how he goes about getting a patient to exercise? What would be your best advice?

Dr. Hill: The first thing I would do is to get people to exercise gradually. I would give them a pedometer, a simple tool for increasing their activity. Now we probably need to get people up to more like an hour a day, but if they are pretty much at zero, it is hard to go from zero to an hour. I would really work on these small changes: give them a pedometer, give them a goal, and have them increase that goal gradually over time and work on increasing their activity over 6 months rather than trying to do it all at once.

Dr. Fujioka: Great. Caroline, when do you decide to start an appetite suppressant or a medication to lose weight? What is it that triggers that for you?

Dr. Apovian: That is a good question. When you see a patient who needs to lose weight, it is important to get a good dietary history and a history of physical activity. The number of weight-loss attempts is also very important.

Many patients who come to see me have already been on numerous diets and numerous weight loss plans -- Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig -- and they may have tried appetite suppressants before. They may have been on liquid diets. The frustrating part for them is they lost weight before, but they have gained it back. Now, they are coming to see you for something else. In that case, in a patient who is let's say weight-loss naive who has not lost weight before on a plan, you can probably give them a diet and exercise plan.

Try to change their behaviors first, though. I would say in the patient who has been on numerous weight-loss plans in the past that is the time to probably start an appetite suppressant with the lifestyle change program that you have for them right away. I wouldn't wait too long because they have shown you already through their history that they have tried this approach, and it hasn't worked for them, so they are ready for another tool that may actually give them a jump start. What you need to do is to show that patient that they can actually lose some weight and maybe keep it off on their own.

Some patients perhaps have been frustrated and lost hundreds of pounds only to regain it back and more. In that patient who has lost weight many times before and regained it back, I would start an appetite suppressant right away or even a fat blocker like orlistat, but the appetite suppressants that we have right now, phentermine and sibutramine, hopefully will be joined by combinations and other drugs if the FDA approves them.

Dr. Fujioka: The last patient who I have, which is probably my hardest -- and I'd love to hear your thought on this, Caroline -- is when we have a patient who is overweight and she is usually a postmenopausal female. We know we are dealing with a lower metabolic rate because as women age they drop very quickly in their metabolic rate. For the postmenopausal female, she is probably depressed just because our society is really tough on women who are overweight. How would you approach that patient medically?

Dr. Apovian: Thank you for mentioning that kind of patient because we have many patients who fall into that category. Seventy-five percent to 80% of persons coming in for weight loss are women, and many of them are postmenopausal. You are right; many are depressed, and the depression stems from the change in their hormonal status.

They become depressed because they have developed less physical activity patterns over the years. Their muscle mass is not what it was years ago when they were more active, so their resting metabolic rate is lower, but it is because of the loss of skeletal muscle mass. The first thing you want to do with a postmenopausal patient who is gaining weight and is depressed is to address the depression, obviously.

The way to address the depression is to try to get that patient to do small bouts of physical activity, maybe with resistance exercise training to get the muscle mass back up. What does the physical activity do? Dr. Hill mentioned physical activity. It makes you feel better about yourself in a rapid fashion. Studies have shown that for patients who have a predisposition for depression, if they do an hour of physical activity a day, they feel better. They are happier.

Now I wouldn't recommend getting someone to start doing an hour of physical activity right away especially if they have been sedentary, but these smaller bouts of physical activity perhaps coupled with some resistance exercise training twice a week can increase their muscle mass, get their muscle mass and their resting metabolic rate up, making them feel better psychologically, and relieve some of that depression. Now I would say that if there is a significant major depressive disorder going on that you diagnose, you need to treat that first before you can implement any long-lasting lifestyle changes.

Dr. Fujioka: All right, great. Well, we have covered a lot. If I am looking at what I am going to take home from this, it is actually a lot of key points, but one is it is clear to at least me anyway -- and I think my colleagues put it very well -- is that you are going to have to look at multiple approaches if you are going to get weight down: diet; exercise; behavior modification; and you may need to think of meds, and again in the very heavy patients think of surgery. You are looking at all of these different things.

• Closing Comments

The other one, it is hard to lose weight. You get beyond just 10% weight loss; if you are 200 lb that is only 20 lb; it is going to be hard to go beyond that because the body makes so many adjustments. It knows it is losing weight and it lowers the metabolic rate. It makes you think about food more. It is tough. I want to thank these top people in the field.

Data for this analysis came from the MacArthur Successful Aging Study, a longitudinal study of high-functioning men and women aged 70 to 79 years at baseline.

The goal of this analysis was to determine the association between BMI, waist circumference, and WHR and all-cause mortality in healthy, high-functioning older adults.

The average age of the participants was 74 years.

Proportional hazards regression was used to adjust for sex, race, age at baseline, and smoking status.

Clinical Implications

In high-functioning older adults enrolled in the MacArthur Successful Aging Study, all-cause mortality was not associated with BMI or waist circumference in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses.In contrast, all-cause mortality rate increased with WHR. In women, there was a graded relationship between WHR and mortality, whereas in men, there was a threshold effect, with mortality rate 75% higher in men with a WHR of more than 1.0 vs men with a WHR of 1.0 or less.

Sibutramine Raises Risk for Adverse Cardiovascular Events

Should the drug be used at all?One reason to encourage weight reduction is to favorably influence risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In this industry-sponsored study, researchers enrolled more than 10,000 overweight or obese people with known cardiovascular disease or with type 2 diabetes plus another risk factor. After a 6-week run-in period during which everyone received the weight-loss drug sibutramine (Meridia), those who tolerated it were randomized to receive sibutramine or placebo. All patients received advice on diet and exercise.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, average weight reduction was 2 kg more in the sibutramine group than in the placebo group. However, the incidence of the primary endpoint (mainly nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death) was significantly higher in the sibutramine group (11.4% vs. 10.0%; P=0.02). A significant excess of adverse outcomes with sibutramine was noted for nonfatal MI and nonfatal stroke, but not for cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Comment: In the U.S., the FDA recently ruled that sibutramine is contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled hypertension; this study confirms the wisdom of that ruling. In fact, the drug should not be used at all, in my view: Compared with placebo, sibutramine resulted in average short-term weight loss of only about 10 pounds in clinical trials, and long-term safety is unclear even in presumably healthy people. A European drug regulation authority has already recommended that the drug be withdrawn.

Journal Watch General Medicine September 2, 2010

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) Apr 01 - A high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet is a safe and effective way for severely obese teenagers to lose weight, according to a new study.

Effective treatment options for young people who are obese are limited, "particularly for those who are severely obese," Dr. Nancy F. Krebs, professor of pediatrics and head of the division of pediatric nutrition at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine and colleagues noted online March 22nd in the Journal of Pediatrics.

High-Protein Low-Carbohydrate Diet an Option in Obese Teens

Fear that a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet in children "could adversely impact growth and could increase cholesterol levels...has been a barrier to it being used," Dr. Krebs told Reuters Health.

To investigate, the researchers randomized 46 severely obese teenagers to eat either a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet or a low-fat diet for 13 weeks. The study subjects were 14 years old on average and were at least 175% above ideal weight, but were free of type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities.

On average, those on the high-protein, low-carb diet lost 29 pounds over 13 weeks, while those on the low-fat diet lost 16 pounds. Nine months later, both groups had maintained the weight loss. "We had expected the high-protein, low-carbohydrate group to quickly regain all the weight lost, but this did not occur," Dr. Krebs said. "At the end of the day, this suggests that with ongoing support, these patients could perhaps have achieved even more weight loss."

The high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet also appeared to be safe, with no serious harmful effects on growth, bone mineral density, and various metabolic parameters, such as cholesterol levels. Both groups had declines in LDL cholesterol and increases in HDL cholesterol.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Angela Celio Doyle of the University of Chicago's eating and weight disorders program, who was not involved in the study, said its findings help "fill the hole" in the scientific literature on adolescent obesity.

"There really isn't any gold standard now for how to help these adolescents lose weight," she said.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cattlemen's Beef Association.

J Pediatr 2010.

Summary

A complex system of brain and peripheral signals entwine to create appetite and satiety. At the hypothalamic nexus, the system is precisely regulated down to the kilocalorie. Select medications across disease entities and therapeutic classes disrupt equilibrium and increase appetite. An evolutionary advantage to the response of appetite stimulation may have existed at one time. However, in the modern era of high caloric intake with comparably low nutrient intake, the deck of cards appears to be stacked against weight maintenance.In some patients the resulting adipose accumulation is significant. However, on a population basis the relative risk for weight gain from medications has not been well quantified. Even if the contribution of medications to obesity is small, the public health impact will be large because of the high prevalence of obesity.

A common mechanism for drug-induced weight gain is appetite deregulation, but an increase in appetite need not translate into excess caloric intake and deposition of body fat. Behavior and lifestyle management, such as the techniques offered in a specialized weight management center, may help maintain weight.

These techniques include eating more slowly and monitoring and limiting caloric intake; staying well hydrated with noncaloric beverages; eating breakfast but not late-night snacks; choosing foods that meet the daily recommended intake of fiber, vegetables, and fruits; and avoiding foods that contain highly processed fats, sugar, and other refined carbohydrates.

Research is needed on how concurrent medications might interact to cause weight gain. Identifying medications that work synergistically to promote weight gain could help guide clinical practice.

Laboratory and genetic testing make it possible to further study how food and nutrients, such as fish, phytonutrient-rich foods, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamin D (to list a few), can be combined with medications in weight management.Methods to improve the uptake of healthful lifestyles can reduce both the need for medications and a medication's obesogenic potential. Such innovations will have a significant impact on public health.

Bupropion plus Naltrexone for Weight Loss?

Adverse effects were mild-to-moderate and transient.The history of drug therapy for obesity is littered with compounds that were marginally effective for weight loss but had unacceptable side effects. Most recently, rimonabant was barred from the U.S. market because of serious neuropsychiatric side effects.Now, the combination of bupropion and naltrexone is being studied for possible weight-loss effects through its synergistic action on appetite signaling and the mesolimbic reward system.

U.S. investigators randomized 1742 obese patients (85% female; mean body-mass index, 36 kg/m2) without diabetes or cardiovascular disease to fixed-dose combinations of bupropion (180 mg twice daily) and naltrexone (either 8 mg or 16 mg twice daily) or to placebo for 52 weeks (following 4 weeks of dose escalation). The study was supported by a company that has combined the two drugs in a single tablet.

About half of the people in each group withdrew from the study, most commonly during the first 16 weeks. In an intention-to-treat analysis, mean weight loss was significantly greater in the high- and low-dose bupropion/naltrexone groups than in the placebo group (–6.1%, –5.0%, and –1.3%, respectively). Adverse effects in the bupropion/naltrexone groups (e.g., nausea, vomiting, constipation, headache, dizziness, dry mouth) were mostly mild-to-moderate and transient.

Comment: Further studies should include broader populations and head-to-head comparisons of bupropion/naltrexone with other active weight-loss agents. An editorialist warns that known psychiatric and cardiovascular side effects of the two component drugs will require careful evaluation.

Journal Watch General Medicine September 2, 2010

A high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet is a safe and effective way for severely obese teenagers to lose weight, according to a new study. Fear that a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet in children "could adversely impact growth and could increase cholesterol levels...has been a barrier to it being used,".

High-Protein Low-Carbohydrate Diet an Option in Obese Teens

To investigate, the researchers randomized 46 severely obese teenagers to eat either a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet or a low-fat diet for 13 weeks. The study subjects were 14 years old on average and were at least 175% above ideal weight, but were free of type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities.

On average, those on the high-protein, low-carb diet lost 29 pounds over 13 weeks, while those on the low-fat diet lost 16 pounds. Nine months later, both groups had maintained the weight loss. "We had expected the high-protein, low-carbohydrate group to quickly regain all the weight lost, but this did not occur," Dr. Krebs said. "At the end of the day, this suggests that with ongoing support, these patients could perhaps have achieved even more weight loss."

The high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet also appeared to be safe, with no serious harmful effects on growth, bone mineral density, and various metabolic parameters, such as cholesterol levels. Both groups had declines in LDL cholesterol and increases in HDL cholesterol.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Angela Celio Doyle of the University of Chicago's eating and weight disorders program, who was not involved in the study, said its findings help "fill the hole" in the scientific literature on adolescent obesity.

April 10, 2012 (Baltimore, Maryland and San Francisco, California) — Differing opinions on the use of statins in primary prevention make the pages of one of the leading medical journals this week, with the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) the latest in a line of professional and mainstream media outlets getting in on the contentious topic [1,2]. Introduced by the JAMA editors to encourage discussion and debate [3], the inaugural "dueling viewpoints" kicks off its new series by considering the clinical question of whether or not a healthy 55-year-old male with elevated cholesterol levels should begin taking the lipid-lowering medication.

Should Statins Be Used in Primary Prevention? JAMA Gets in on the Debate

2012 Medscape

The two "combatants" in the clinical duel will also be familiar, having previously debated the topic in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, as well as on theheart.org. For Drs Rita Redberg and William Katz (University of San Francisco, California), who argue that healthy men should not take statins, there are other effective means to reduce cardiovascular risk, including dietary changes, weight loss, and increased exercise.

"These strategies are effective in increasing longevity and also result in other positive benefits, including improved mood and sexual function and fewer fractures," they write. "Although these strategies are challenging, prescribing a statin may undermine them. For example, some patients derive a false sense of security that because they are taking a statin they can eat whatever they want and do not have to exercise."

In their counterpoint, Drs Michael Blaha, Khurram Nasir, and Roger Blumenthal (Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease, Baltimore, MD) agree that the cornerstone of treatment for patients with elevated cholesterol levels will always be diet and exercise but that statins can be a "critical adjunct for those identified to be at increased coronary heart disease risk." The Johns Hopkins physicians argue that there is no logic in waiting for an MI to occur before starting statin therapy and that if clinicians are unsure of the risk of seemingly healthy patients with elevated cholesterol levels, the use of coronary artery calcium (CAC) screening can help.

"The CAC scan is a helpful tool that enables clinicians to direct statin treatment at the disease (coronary atherosclerosis) that they propose to treat and illustrates the concept of risk-based, individualized decision making," write Blaha, Nasir, and Blumenthal. "Statin therapy would not be recommended if a CAC scan revealed a score of 0."

In their viewpoint, they point to data from WOSCOPS and AFCAPS/TexCAPS showing reductions in MI and other coronary events in the primary-prevention setting. However, they argue that the debate over cholesterol therapy needs to be rephrased, because doctors should never treat elevated cholesterol levels in isolation but instead aim to provide therapy to the highest-risk patients most likely to benefit.

For Redberg and Katz, however, the data simply do not support the use of statins in the 55-year male patient with normal blood pressure and no family history of disease but with elevated cholesterol levels.

They point to a recent meta-analysis in healthy but high-risk men and women showing no reduction in mortality with statin therapy, as well as a recent Cochrane review showing similar results. Moreover, Redberg and Katz highlight the adverse effects associated with statins, including cognitive defects and diabetes.

"For every 100 patients with elevated cholesterol levels who take statins for five years, a myocardial infarction will be prevented in one or two patients," they write. "Preventing a heart attack is a meaningful outcome. However, by taking statins, one or more patients will develop diabetes and 20% or more will experience disabling symptoms, including muscle weakness, fatigue, and memory loss."

2012 Medscape

The Five Rules of The Leptin Diet

There are five simple rules that form the core of The Leptin Diet®. The quality of the food you eat is of course important. What is interesting about The Leptin Diet is that it is just as important when you eat as what you eat.The Leptin Diet is the secret to getting more energy from less food. The scientific principles upon which it is based are unlikely to ever change.

This is not a fad diet, a calorie manipulation scheme, or a starvation routine masquerading as a diet. It does not involve deprivation of pleasure. The underlying principles of The Leptin Diet apply to everyone, whether you need to lose weight or not. It is a lifestyle for eating properly grounded in the science of leptin. It is something you can do happily and healthfully over the long haul

The Five Rules of the The Leptin Diet: Rule 1: Never eat after dinner. Rule 2: Eat three meals a day. Rule 3: Do not eat large meals. Rule 4: Eat a breakfast containing protein. Rule 5: Reduce the amount of carbohydrates eaten

RULE 1: NEVER EAT AFTER DINNER

Allow 11-12 hours between dinner and breakfast. Never go to bed on a full stomach. Finish eating dinner at least three hours before bed.One of leptin’s main rhythms follows a 24-hour pattern. Leptin levels are highest in the evening hours. This is because leptin, like the conductor in the orchestra, sets the timing for nighttime repair. It coordinates the timing and release of melatonin, thyroid hormone, growth hormone, sex hormones, and immune system function to carry out rejuvenating sleep. It does this while burning fat at the maximum rate compared to any other time of the day. And it does this only if you will allow it, by not eating after dinner.

It is pretty obvious when this isn’t working so well. Your extra carvings for food may begin around 4 o’clock in the afternoon and certainly later in the evening. These cravings are powered by a misguided leptin signal to eat, causing strong urges that often overwhelm your will power and self control. If you are in this situation you will find yourself circling the refrigerator and cupboards, like an animal hunting its prey. You will find excuses to obtain food and often will then plop yourself in front of the TV and begin to eat. This is the leptin nightmare, the drive to acquire food even though rationally you know you don’t need it.

Make every effort to not eat after dinner at night

RULE 2: EAT THREE MEALS A DAY

Allow 5-6 hours between meals. Do not snack.

It is vital to create times during the day when small fat blobs, known as triglycerides, are cleared from your blood. If triglycerides build up during the day they physically clog leptin entry into your brain, causing leptin resistance – meaning that leptin cannot register properly in your subconscious command and control center. Your metabolism is not designed to deal with constant eating and snacking. Doing so confuses your metabolism and results in you eating much more than you really need. Eating too often is like a repetitive strain injury, like tennis elbow but in this case leptin elbow.

Yes, you are supposed to get a snack between meals – but it is supposed to come from your liver. This is how your body naturally clears triglycerides from your blood. Besides that fact that these fat blobs confuse leptin, they are also headed in the direction of your hips, thighs, and stomach. So breaking them down and clearing them out is vital, and this only happens when you allow 5-6 hours between meals. When you clear your circulatory highways of extra fat during the day then leptin works better. When you do a great job during the day then you are much more likely to break down and burn stored fat from your hips and thighs while you are sleeping.

Snacking turns out to be one of the worst things you can do. It doesn’t matter how many calories you snack on, when you snack you throw powerful hormonal switches that cause leptin to malfunction. The fictitious idea that snacking is needed to stoke your metabolism or maintain your blood sugar is in no small part behind dietary advice that has helped cause an epidemic of obesity.

RULE 3: DO NOT EAT LARGE MEALS

If you are overweight, always try to finish a meal when slightly less than full, the full signal will usually catch up in 10-20 minutes. Eating slowly is important. As you improve you will start getting full signals at your meals – listen to this internal cue and stop eating.One of the traits of the non-obese French population, that is before the American junk food industry swooped down upon them, is that their people listen to the internal full signal..

In America, especially in those who are overweight, portion size is determined by what is available – this is called the see food diet – what you see is what you eat.

Unless you are a super active individual with very high physical output of energy, the fastest way to cause leptin problems is to eat large meals. It does not matter if the meal is composed mostly of fat, carbohydrate, or protein. Consistently eating large meals is the easiest way there is to poison your body with food

RULE 4: EAT A BREAKFAST CONTAINING PROTEIN

Your metabolism can increase by 30% for as long as 12 hours from a high-protein meal; the calorie-burning equivalent of a two to three mile jog. A high-carbohydrate breakfast such as juice, cereal, waffles, pancakes, or bagels does not enhance metabolic rate more than 4%, especially when eaten with little protein.This rule is especially important for individuals who struggle with energy, food cravings, and/or body weight. In general, it is a necessity for anyone over the age of 40. While some people may be able to run their metabolism just fine on a higher carbohydrate breakfast for a number of years, this tends not to be the case for any person struggling with their weight.

The two signs of a poor breakfast are:1) You are unable to make it five hours to lunch without food cravings or your energy crashing.2) You are much more prone to strong food cravings later that afternoon or evening. Eggs are a good breakfast, just not smothered in butter and cheese. Cottage cheese is another high protein breakfast food, and along with a serving of complex carbohydrate or fruit makes a great breakfast. Even a few tablespoons of peanut butter or almond butter (not half the jar) on a piece of toast could work well, especially if you are in a hurry.

I like high-efficiency whey protein for quick and easy breakfasts, such as our Daily Protein Plus. It is quality protein that gets you metabolism started on the right foot and will keep you more stable during the day.

RULE 5: REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF CARBOHYDRATES EATEN

Carbohydrates are easy-to-use fuels. If you eat too many of them there is no need for your body to dip into its savings account. It is very important that you eat some carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are needed or your thyroid turns off, electrolytes become dysregulated, muscles weaken, growth hormone is not released correctly, fat is not burned efficiently, there is an unsatisfied feeling after a meal, your heart can become stressed, and your digestive system may go on the blink. I certainly do not advocate a no-carbohydrate diet. You don’t want to make yourself into a carbohydrate cripple.

However, most overweight individuals eat two or more times the amount of carbohydrates they are able to metabolize. If you are trying to lose weight an easy way to do this is what I call the 50/50 technique. Look at the food on your plate. You want to see a palm-size portion of protein (a 4-6 ounce portion for women; 6-8 ounce portion for men). And then you want to see a palm size amount of the carbohydrates, a 50/50 visual. This way there is no calorie counting. Compare the protein (chicken, meat, turkey, eggs) to the carbohydrates (bread, rice, pasta, potatoes, fruit, corn, squash, etc,). Fill up on fiber rich vegetables as desired.

If you think you really need more food than this, then take a tablespoon or two of good soluble fiber before you eat, like our Fiber Helper or our LeptiFiber, and you will not only feel more full on less food but your insulin and leptin response to your meal will be smoothed out and in many cases enhanced.

In summary, one key take home message about the science of leptin is that it is just as important when you eat as what you eat. Eating throws powerful hormonal switches. Make sure you throw them at the right time so that your body can do what it was intended to do. When you eat in harmony with leptin your head will feel clearer and your energy better, your cravings will go away, and your health will improve. There is a lot of power in these five simple rules.