د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Herpes simplex encephalitisEASILY MISSED?

BMJ 6 June 2012The wife of a previously healthy 40 year old man requested adomiciliary visit from their general practitioner for her husband,who had been in bed for a few days with “bad flu,” fever, and headache. She was worried that he was becoming quite confused and unable to recall recent events. The GP finds the patient is febrile, agitated, and disoriented in time and place. Concerned about encephalitis, he sends the patient immediately to hospital.

There a CT scan shows an area of decreased attenuation in the right temporal lobe and a lumbar puncture a raised lymphocyte count, both suggesting herpes simplex encephalitis. Aciclovir treatment is immediately started.

What is herpes simplex encephalitis?

Herpes simplex encephalitis is a severe viral infection of the central nervous system that is usually localised to the temporal and frontal lobes in adults. Typically, it causes a flu-like illness with headache and fever followed by seizures, cognitive impairment, behavioural changes, and focal neurological signs, but its presentation is variable.Why is it missed?

The clinical presentations of herpes simplex encephalitis are varied. The viral prodrome may be absent, and the cognitive impairment may be subtle. Focal neurological features can be mistaken for stroke, seizures for primary epilepsy, cognitive impairment for non-specific delirium, and behavioural changes for a primary psychiatric disorder. Clinicians may be reluctantto perform invasive testing unless viral encephalitis is strongly suspected. A recent analysis of 16 cases presenting between 1993 and 2005 showed that there were often substantial delays in performing examinations of cerebrospinal fluid..

Even when investigations are performed early in the course of the disease, results may be misleadingly negative: cerebrospinal fluid cell count is normal in 5–10% of patients, particularly in children;

computed tomography results are normal in the first week of illness in up to a third of patients; magnetic resonance images are normal in 10%; and detection of viral DNA by the polymerase chain reaction can be negative initially.

Why does this matter?

Herpes simplex encephalitisis uncommon but has high mortality and morbidity if treatment with aciclovir is not given or delayed.Aciclovir inhibits viral replication and prevents extension of the disease within the brain, thereby reducing mortality from more than 70% in untreated patients to 19%.

The most common result of delayed treatment is neuropsychological impairment, with amnesia because of selective involvement of the limbic system.

In the well known case of the celebrated pianist and conductor Clive Wearing, diagnosis was delayed for five days, and he survived with permanent and profound anterograde amnesia.

Several costly medicolegal claims have resulted from similar delays in diagnosis.

How is herpes simplex encephalitis diagnosed?

Clinical featuresThere is usually a prodrome of malaise, fever (90%), headache (81%), and nausea and vomiting (46%) lasting for a few days, consistent with a viral infection.

On this background, features raising suspicion of encephalitis include the concurrent onset of

• Progressive alterations of behaviour (71%)

• Features suggestive of focal epilepsy (67%), such as

olfactory hallucinations or periods of altered awareness • Focal neurological signs(33%),such as unilateral weakness • Cognitive problems (24%), such as difficulty in word finding, memory impairment, or confusion.

Investigations

If herpes simplex encephalitis is suspected, brain imaging(magnetic resonance imaging if possible, otherwise computed tomography) and cerebrospinal fluid analysis(if lumbar puncture is not contraindicated, such as by mass effect or coagulopathy) should be performed urgently.

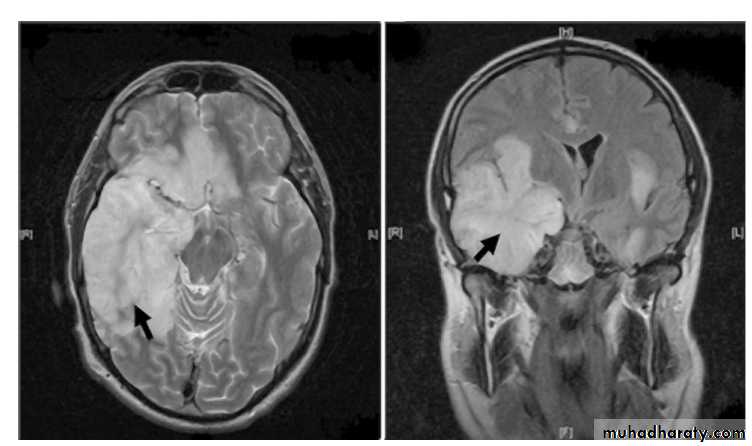

Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging modality of choice, and is abnormal in 90% of patients (figure⇓).

Brain imaging both helps to support the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis and to exclude contraindications to lumbar puncture. It typically shows unilateral or asymmetric bilateral high signal in the medial temporal lobes, insular cortex, and orbital surface of the frontal lobes (best seen with fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI)). These changes are not specific for herpes simplex.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of limbic encephalitis (such as paraneoplastic or autoimmune limbic encephalitis), gliomatosis

cerebri (a rare primary brain tumour), middle cerebral artery ischaemia, and possibly the effects of status epilepticus.

The cerebrospinal fluid typically shows a raised lymphocyte count (10–500×106/L, average 100×106/L),sometimes with red blood cells with or without xanthochromia, reflecting the haemorrhagic nature of the encephalitis, mildly raised protein

levels, and normal or mildly decreased glucose. Definitive diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitisis made by the detection of viral nucleic acid in the cerebrospinal fluid by the PCR . This test has a sensitivity of 96–98% and specificity of 95–99% and has removed the need for brain biopsy.

It remains positive for at least five to seven days after

starting antiviral therapy.Viral DNA may be undetectable in early disease, but, if so, a repeat examination by polymerase chain reaction on cerebrospinal fluid three to seven days later

can clinch the diagnosis.

Electroencephalography has a high sensitivity (84%) but low specificity (32%) for the diagnosis of herpes simplex

encephalitis.

However, it can be helpful in identifying non-convulsive seizure activity, which will benefit from anticonvulsant treatment.

How is herpes simplex encephalitis managed?

Pending the confirmation of the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis, all adults with suspected encephalitis should be given aciclovir empirically, at a dose of 10 mg/kg, administered as intravenousin fusions over one hour and repeated every eight hours for 14-21 days if renal function is normal.Higher doses are recommended for immunocompromised patients. If bacterial meningitis is considered a possibility, appropriate antibacterial therapy should also be given. Should seizures occur, they are treated with anticonvulsants along standard lines. Raised intracranial pressure will occasionally require treatment. The role of adjunctive corticosteroids is not yet established.

Key points

Herpes simplex encephalitis is highly treatable, but can cause death or severe neuropsychological impairment if untreated• The diagnosis is suggested by acute or subacute onset of Alterations of behaviour

• Focal or generalised seizures

• Focal neurological signs

• Cognitive difficulties

• Usually on a background of fever and headache

If it is suspected perform urgent brain imaging (preferably magnetic resonance imaging) and cerebrospinal fluid analysis for microscopy

and DNA testing (if lumbar puncture is not contraindicated), bearing in mind that these may be normal early in the course of the disease Start intravenous aciclovir immediately if the diagnosis is suspected

Axial and coronal T2 weighted magnetic resonance images showing areas of hyperintensity (arrowed) corresponding to

oedematous changes in the temporal lobes and inferior frontal lobes with mass-like effect due to herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Reproduced with permission of Southampton General Hospital’s picture library

A doctor’s perspective

Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is the most commonly diagnosed viral encephalitis in the United Kingdom, with an annual incidenceestimated at 2-4 per million. Although in the 1980s the mortality improved with the introduction of aciclovir, the morbidity remains high,

especially when treatment is started late. Recent work by our group, and others, looking at where the delays occur and why, has resulted

in the development of new national encephalitis guidelines (see “Useful resources” box), which should encourage better management.

In Darren’s case there were no delays in treatment. He was admitted to hospital on the day he developed altered consciousness; in retrospect, the apparently disgusting smell of food was probably an olfactory hallucination, which may be an early clue to herpes encephalitis. In hospital the constellation of a febrile illness and abnormal behaviour was quickly recognised as an indicator of possible brain infection; the lumbar puncture was consistent with viral disease, and aciclovir was started, all within a few hours of admission. However, Darren’s outcome shows that despite rapid treatment, the effect of herpes simplex virus on the brain can still be catastrophic, both for the patient and the family.

The importance of the Encephalitis Society in helping Darren and his family to cope with the illness is also very apparent.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is transmitted through droplets and is thought to enter the central nervous system via the olfactory nerve, which sends branches to the temporal lobes, hence the characteristic damage to this part of the brain in herpes encephalitis. The medial temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus, is important in laying down new memories (anterograde memory); this explains why anterograde memory is so often affected in herpes encephalitis.

In Darren’s case, in addition to anterograde amnesia, there is memory loss for events before the

illness—retrograde amnesia. His knowledge of facts, semantic memory, is also affected, with a striking inability to recall the names of common

objects. Perhaps most extraordinary of all, though, is that despite his difficulties with English, Darren’s French language skills were relatively preserved.

Whereas verbal memory is strongly left lateralised in the medial temporal lobe, learning of foreign language is thought to reside in the right hemisphere; and clearly in Darren’s case this has made an enormous difference to the sequelae of his disease.

But beyond the fascinating insights it gives us into how the brain works, this case highlights the need for further research on disease mechanisms in encephalitis, and the role of anti-inflammatory treatments as adjuncts to antiviral drugs.

Tom Solomon, professor of neurological science