Life expectancy in HIVBetter, but not good enough

BMJ 2011د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

More than 33 million people are infected with HIV worldwide.Over the past 30 years, mortality from HIV and the life expectancy of people who are infected have improved dramatically. With major advances in biomedical research,increased awareness, and dedicated funding, HIV has been

transformed from an untreatable and almost always fatal disease to a chronic one.

For patients diagnosed promptly and treated

with combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), life expectancy is now several decades. In the linked cohort study (doi:10.1136/ bmj.d6016), May and colleagues estimate specific life expectancy for people in the United Kingdom with HIVundergoing treatment compared with life expectancy in the general population.

Gains in life expectancy have increased steadily over time, with the availability of more effective and better tolerated regimens.

But these gains have not been seen in everyone with HIV.

Factors associated with worse outcomes

• late presentation to healthcare services,

• suboptimal adherence to drugs,

• premature discontinuation of treatment,

• mental illness, and behavioural risk factors such as use of injected drugs and

• Alcohol dependence.

Data from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) suggest that more than 80 000 people are currently living with HIV in the UK, and about 25% of them are unaware of their infection.5 These people, their healthcare providers, and policy makers confront several key questions.

• How much life expectancy is lost as a result of HIV?

• How does the timing of the start of treatment affect life expectancy?

• Do losses in life expectancy as a result of HIV differ between men and women?

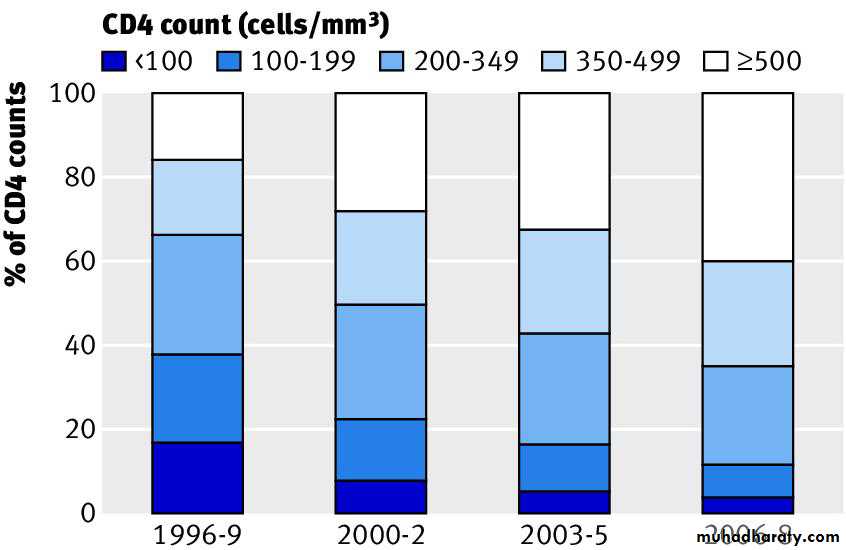

May and colleagues report estimates of life expectancy derived from a large cohort study of patients who started HIV treatment between 1996 and 2008 at some of the largest clinical centres in the UK. The authors suggest that between the periods 1996-9

and 2006-8, the

life expectancy of an average 20 year old person infected with HIV increased from 30 to 46 years.

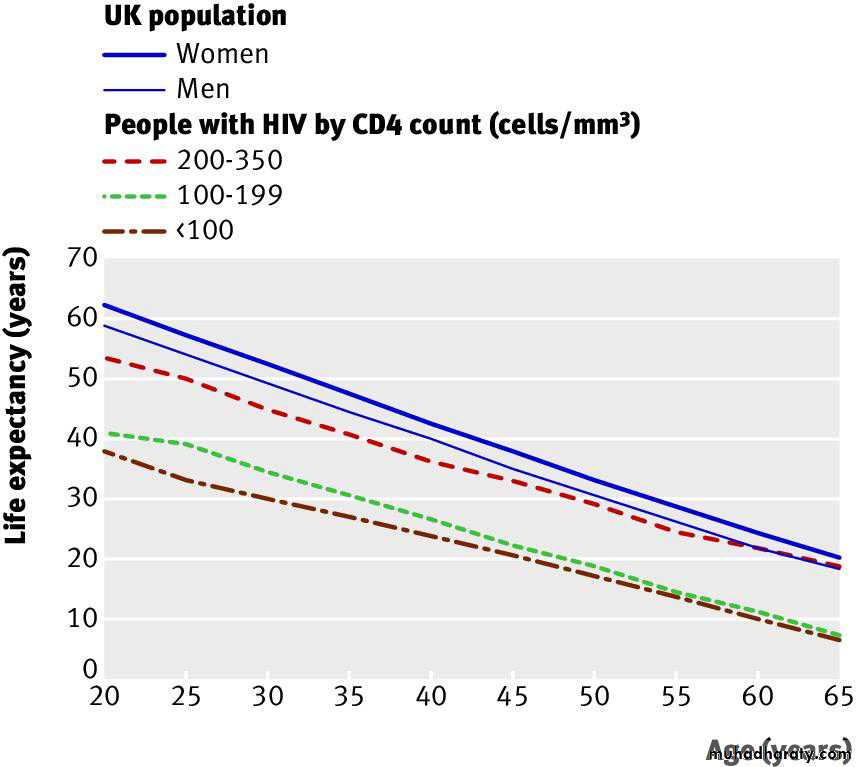

The authors also found that decreases in life expectancy as aresult of HIV are greater in men than in women. They estimate that, for an average 20 year old man, HIV decreases life expectancy by 18.1 years; in contrast, a woman loses only 11.4 years. Why is the difference so large? Data from other countries show that women are likely to start treatment for HIV earlier than men, perhaps partly because women are often tested for HIV during pregnancy. Because earlier care is associated with better survival, this may explain the differences between men and women.

May and colleagues found greater reductions in life expectancy

(more than 15 years lost) in those who start ART late(CD4 counts <100×106/L) rather than early (CD4 counts 200-350×106/L), providing more evidence in favour of earlier treatment. The presentation of information in terms of gains in life expectancy makes this important message easily understood by patients. For health related messages to be effective, people must perceive a problem as relevant and serious, and they should recognise that change provides clear gains. This study provides clinicians with the language to make these gains real.

May and colleagues’ study is an excellent example of

acomprehensive analysis conducted on a well defined longitudinal cohort. However, the estimates should be interpreted within the boundaries of the data from which they are derived. The UK Collaborative HIV Cohort comprises data from referral centres.Although it is easier to conduct studies in high volume regional centres, not all HIV infected patients receive care in such settings. Patients of higher socioeconomic status are often over-represented in high volume clinics because those on low incomes and those in racial and ethnic minorities often receive care in lower volume centres.

High volume referral centres are associated with better outcomes.

The right censored nature of cohort data should also be takeninto account. Participants are more likely to contribute early years on treatment, when mortality is lower, and to be censored later (because the follow-up period ends), when mortality is likely to rise.

Because of the artificial right censoring that occurs

when data are closed for analysis, people who started ART in 2006-8 had less follow-up time to contribute, which would also result in overestimation of recent survival and life expectancy.

Comparing life expectancy in people with HIV with that of the general population may misattribute losses to HIV that really come from other behavioural factors, such as smoking, substancemisuse, and mental illness. Comparing life expectancy in those with and without HIV, but with similar risk factors, could shed light on this.May and colleagues’ study serves as an urgent call to increase awareness of the effectiveness of current HIV treatments in patients and providers. In turn this should increase rates of routine HIV screening, with timely linkage to care and uninterrupted treatment. As these factors improve, the full benefits of treatment for all HIV infected people can be realised.

BMJ 2011

Impact of late diagnosis and treatment on lifeexpectancy in people with HIV-1: UK Collaborative HIV

Cohort (UK CHIC) Study

BMJ 24 August 2011

Abstract

Objectives To estimate life expectancy for people with HIV undergoing treatment compared with life expectancy in the general population and to assess the impact on life expectancy of late treatment, defined asCD4 count <200 cells/mm3 at start of antiretroviral therapy.

Design Cohort study.

Setting Outpatient HIV clinics throughout the United Kingdom. Population Adult patients from the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study with CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3 at start of antiretroviral

therapy in 1996-2008.

Main outcome measures Life expectancy at the exact age of 20 (the average additional years that will be lived by a person after age 20),

according to the cross sectional age specific mortality rates during the study period.

Results 1248 of 17 661 eligible patients died during 91 203 person years’ follow-up.

Life expectancy (standard error) at exact age 20 increased from 30.0 (1.2) to 45.8 (1.7) years from 1996-9 to 2006-8.

Life expectancy was 39.5 (0.45) for male patients and 50.2 (0.45) years for female patients compared with 57.8 and 61.6 years for men and women

in the general population (1996-2006).

Starting antiretroviral therapy later than guidelines suggest resulted in up to 15 years’ loss of life:

At age 20, life expectancy was 37.9 (1.3), 41.0 (2.2), and 53.4 (1.2) years in those starting antiretroviral therapy with CD4 count <100, 100-199,

and 200-350 cells/mm3, respectively.

Conclusions Life expectancy in people treated for HIV infection has increased by over 15 years during 1996-2008, but is still about 13 years less than that of the UK population. The higher life expectancy in women is magnified in those with HIV. Earlier diagnosis and subsequent timely treatment with antiretroviral therapy might increase life expectancy.

Introduction

HIV infection has become a chronic disease with a good prognosis provided treatment is started sufficiently early in the course of the disease and the patient is able to maintain lifelong adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Mortality rates have decreased such that, compared with the general population, the risk of death in successfully treated patients is similar to that of people with unhealthy lifestyles (such as heavy smoking, drinking, or obesity) or other chronic conditions such as diabetes.Although previous studies have compared mortality

rates in patients with HIV with those in the general population or have reported the prognosis of patients with HIV by estimating cumulative probability of death, few have estimated how long those with HIV are likely to live.Estimates of life expectancy are important to individuals who want to plan their lives better, to service providers, and to policy

makers. Patients might use this information to inform decisions on when they start antiretroviral therapy and treatment of comorbidities, pension provision, starting a family, or buying a house.

We estimated life expectancy in those treated for HIV infection and compared this with the life expectancy of the general population in the UK using data from the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study11 for 1996-2008. We also estimated the loss in life expectancy of those who start antiretroviral therapy at a more advanced stage of the disease than recommended by national treatment guidelines and quantified the potential years of life lost as a measure of the burden of HIV disease at the population level in the UK.

Discussion

The life expectancy of people with HIV treated with antiretroviral therapy in UK hospital clinics has substantially increased over the period 1996-2008, but remains much lower than that of the UK population. Women have a higher life expectancy than men, which is only partially accounted for by sex differences in the life expectancy of the background population. Most importantly, life expectancy is strongly related

to the CD4 count at which individuals start treatment.

Patients who were diagnosed late or deferred treatment until their CD4 count fell to below 200 cells/mm3 were estimated to have a life expectancy at age 20 at least 10 years less than those who conformed to current treatment guidelines, which suggest that patients should start antiretroviral therapy once their CD4 count has fallen below 350 cells/mm3.

Furthermore, the effect of delayed diagnosis and treatment is worse than our results suggest

as some people die without ever starting antiretroviral therapy.

This highlights the need to identify people infected with HIVearly in the course of their infection, before substantial CD4 loss has occurred.

Implications of findings

The improvement in life expectancy since 1996 is probably due to several factors: a greater proportion of patients with high CD4 counts, better antiretroviral therapy, changing demographics of the population of patients (namely, more women and immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa), and an upward trend in the population life expectancy.The patients treated in earlier years started therapy with more advanced HIV disease, were more likely to develop drug resistant HIV because of pre-treatment with one or two antiretroviral drugs, and received regimens that were inferior to those currently prescribed in terms of viral suppression, pill burden, toxicity, and serious adverse effects.

Improvements in treatment are unlikely to be only pharmacological: increasing experience among physicians

could also have affected survival. Non-adherence to treatment can result in the development of drug resistance, which limits the number of treatment options available to patients.

Interruptions to treatment are associated with increased risk of virological rebound and serious non-AIDS events, as reported by the Strategies for Management of Anti-Retroviral Therapy (SMART) trial.

Interrupting treatment probably became less common after the results of the trial were reported, which could have contributed to the increase in life expectancy after 2006. Modern first line regimens are more robust than earlier regimens. There has been a decline in transmission of drug resistant virus, and adherence has been improved by once daily treatment and coformulation of medications, all of which

contribute to better virological control and, ultimately, greater life expectancy.

The higher life expectancy in women in the general population is magnified in those with HIV. This could be because of earlier diagnosis through screening in antenatal clinics before women have a low CD4 count, late presentation in men, or sex differences in lifestyle factors that are exaggerated in patients (for example, smoking, alcohol, and drug misuse are common in men who have sex with men but not in women from sub-Saharan Africa). Alternatively, there could be bias from loss to follow-up and consequent under-ascertainment of death in women.

It is important to further understand this discrepancy

and formulate policy to ensure that there are equal opportunities to achieve the same outcome in men and women. The data on life expectancy stratified by CD4 count show that an important driver of the lower life expectancy in people with HIV compared with the general population is that patients started treatment at a lower CD4 count than recommended by guidelines.At the start of treatment, mortality is highest for those with lowest CD4 count, and even in those who survive the first three years of treatment, CD4 count at start of antiretroviral therapy remains prognostic. A review of deaths among treated patients with HIV in the Royal Free Hospital in London from 1998 to 2003 cited late presentation, delayed uptake of antiretroviral therapy, and previous use of treatment combinations now viewed as suboptimal as contributory factors.

A high proportion of patients in UK CHIC started

treatment with CD4 count <200 cells/mm3.32 This proportion is consistent with that seen in many other European settings, where many people do not receive a diagnosis of HIV infection untiltheir CD4 counts have already fallen to low levels.

Late presentation, however, is only a partial explanation: patients, particularly if they have no symptoms, might have delayed starting treatment because of a reluctance to embark on a lifelong commitment to take antiretroviral drugs, many of which have a poor toxicity/tolerability profile. Before starting treatment,many patients had substantial gaps between CD4 assessments,reflecting irregular clinic attendance.

In addition to deaths from AIDS defining diagnoses, people with HIV experience higher rates of non-AIDS deaths than the general population, which could be due to HIV infection,adverse events associated with treatment for HIV, or lifestyle factors. The prevalence of smoking, drug misuse, and alcoholism

are all higher among people with HIV, which leads to increased deaths from cardiovascular disease, cancer, liver disease, suicide.

The Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research in Europe (COHERE) found that death rates among men, but not women,with CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3 reached those of the matched general population after at least three years’ receipt of antiretroviral therapy with counts above that threshold. These studies show what can be achieved if patients receive an early diagnosis, avoid compromising their immune system and the

attendant morbidities35 and are successfully treated to restore their CD4 count to a level approaching normality.

Life expectancy among people with HIV has considerably improved in the UK between 1996 and 2008, and we should expect further improvements for patients starting antiretroviral therapy now with improved modern drugs and new guidelines recommending earlier treatment. Our study shows the longevity of patients who started antiretroviral therapy with a CD4 count of 200-350 cells/mm3. These data can be incorporated into models for life insurance, pensions, and healthcare planning, but most of all communicated to patients to help them manage their lives better.

Conclusions

Furthermore, the clear impact of low CD4 count on life expectancy implies that it is particularly important to diagnose HIV infection at an early stage. This would benefit both patients and healthcare systems as the patient would experience increased life expectancy and the healthcare system a reduction in the costs associated with lower CD4 count at diagnosis, including hospital treatment or admission, or both.

Our findings strongly support the concept of more widespread testing for HIV, especially initiatives to achieve universal testing. It is also of clear benefit to the patient to have the prognosis made in terms of their life expectancy, and this might have considerable impact on patients’ uptake of testing.

What is already known on this topic

Life expectancy is an important health indicator that informs decisions by individuals and public policy makers Life expectancy in people treated for HIV infection in industrialised countries has been estimated to be much lower than that of thegeneral population .

What this study adds

In the UK, life expectancy (at the exact age of 20) in those treated for HIV infection has increased by 15 years over the period 1996-2008,but is still about 13 years less than that of the UK population .The higher life expectancy of women compared with men is magnified among people with HIV.There is a need to identify people with HIV early in the course of disease to avoid the large negative impact that starting antiretroviral therapy at a CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3 has on life expectancy.

BMJ 24 August 2011

Fig 1 Distribution of current CD4 count by period of follow-up

Fig 2 Life expectancy from age 20-65 of people who started antiretroviral therapy in 2000-8 by CD4 cell count group at start of antiretroviral therapy compared with that of UK population (2000-6 women and men)