د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

management ofechinococcosis

BMJ 11 June 2012Echinococcosis (hydatid disease) is caused by the larvae of dog and fox tapeworms(cestodes) of the genus Echinococcus(family

Taeniidae).

This zoonosisis characterised by long term growth

of metacestode (hydatid) cysts in humans and mammalian intermediate hosts. The two major species that infect humansare E granulosus and E multilocularis, which cause cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE). A few reported cases of polycystic echinococcosisin Central and South America are caused by E vogeli and E oligarthrus.

The clinical potential of two other Echinococcusspecies(E shiquicusand E felidis) is unknown.

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE) are serious chronic diseases with poor prognosis and high mortality if managed inadequately.

Of the estimated two to three million cases of echinococcosis globally, most are cystic.

Published reports and the Office International des Epizooties databases suggest that the global burden for human CE exceeds one million disability adjusted life years (DALYs).

Case series and small clinical trials show a mortality rate of 2-4% for CE, but this increases markedly with poor treatment and care.

There are 0.4 million cases of human AE, and survival analysis has shown that, if untreated or if treatment islimited, mortality exceeds 90% 10-15 years after diagnosis. About 18 000 new cases of AE occur annually.

Here, we introduce the Echinococcus parasites and the diseases they cause, and we discuss current methods for the diagnosis,treatment, and management of both types of echinococcosis.

The life cycle characteristics of Echinococcusspp and the causes and immunology of echinococcosis have been described extensively.

Where and how is echinococcosis acquired?

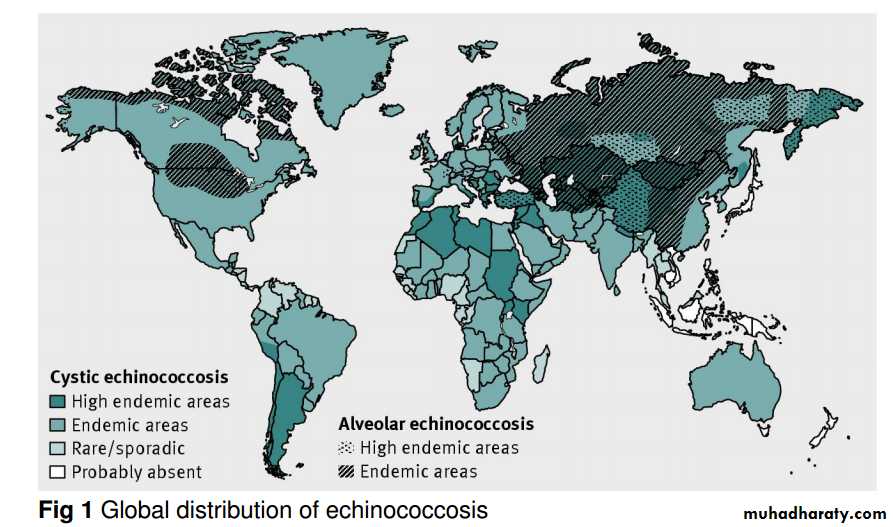

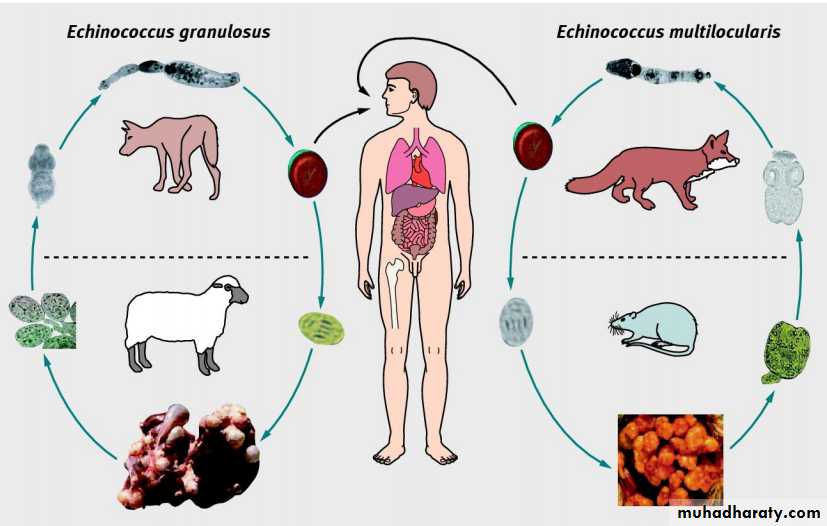

Figure 1⇓ shows the distribution of echinococcosis, according to statistics from the World Health Organization. E granulosus occurs worldwide, with high endemic areas concentrated in north east Africa, South America, and Eurasia.E multilocularisisrestricted to the northern hemisphere.Figure 2⇓ illustrates the E granulosus and E multilocularis life cycles and shows how humans become infected. Human co-infection with E granulosus and E multilocularisis not common, although these two species are co-endemic in some specific foci, notably the northwest of the People’s Republic of China.

Figure 3⇓ is an ultrasound image of a patient with both types of echinococcosis.

What are the clinical features of echinococcosis?

Most (>90%) CE cysts occur in liver, lung, or both organs.In general, the initial stages of CE do not cause

symptoms—small cysts can remain asymptomatic for many Years. Because of the parasite’s slow growth most cases are diagnosed in adults.

The onset of symptoms depends on the infected organ, the size and position of the cyst(s), their effect on the organ and adjacent tissues, and complications arising from the rupture of a cyst or a secondary infection.

Recurrent (secondary) CE can arise after primary cyst surgery, owing to spillage of the cyst contents, or if there isspontaneous or trauma induced cyst rupture and release of larvae, which can grow into secondary cysts. Leakage or rupture of CE cysts can induce systemic immunological reactions and other complications,including cholangitis.

AE generally has a longer latent phase (up to 15 years) before the onset of chronic disease.

E multilocularis usually developsin the right liver lobe and AE lesionsrange from a few

millimetres to 15-20 cm in diameter in areas of infiltration.

Extrahepatic primary disease is uncommon.

Metastasis formation leads to secondary AE with infiltration of the lung,spleen, or brain. Symptoms of AE usually include epigastric pain or cholestatic jaundice.

How is echinococcosis diagnosed?

The box shows the best indicators of disease. The diagnosis of CE is based on clinical findings, imaging results, and serology.

Clinical manifestations may indicate cyst

rupture, secondary bacterial infection, allergic reactions, or anaphylaxis.

Patients with symptoms should immediately be

advised to undergo imaging and serology.

Ultrasound is a crucially important tool for the diagnosis,staging, and follow-up of abdominal CE cysts, although it has low sensitivity for detecting small cysts. The first generally accepted ultrasound classification for CE was developed in1981.

A series of meetings by aWHO informal working group on echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE) resulted in an international standardised ultrasound classification of CE cysts into threegroups (fig 4⇓).

Microscopy of cystic fluid for brood capsules or protoscoleces provides proof of infection and cyst viability.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of biopsy material can also provide a definitive diagnosis.

High field magnetic resonance spectroscopy is also useful for determining cyst viability and for staging.

CE serology is a helpful diagnostic adjunct and can be used to monitor patients after surgery or drug treatment. However,although used widely, particularly in developing countries where imaging techniques may not be readily available, questions remain with regard to its effectiveness for clinical detection and Screening.Serum antibody measurement is more sensitive than detection of circulating E granulosus antigens, But available tests lack standardisation.

Current serology for human CE mainly tests for IgG antibodies against native or recombinant antigen B by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay or western blotting.

Test specificity is affected by immunological crossreactivity with antigens found in other

helminth infections, cancers, and liver cirrhosis and by the presence of anti-P1 antibodies.

Although not thoroughly tested, serodiagnostic performance seems to depend also on cyst location, cyst size, and stage.

The seriousness of human AE means early detection is crucial so that treatment can start.

Diagnosis is analogous to that for CE including clinical findings and use of imaging techniques and serology.

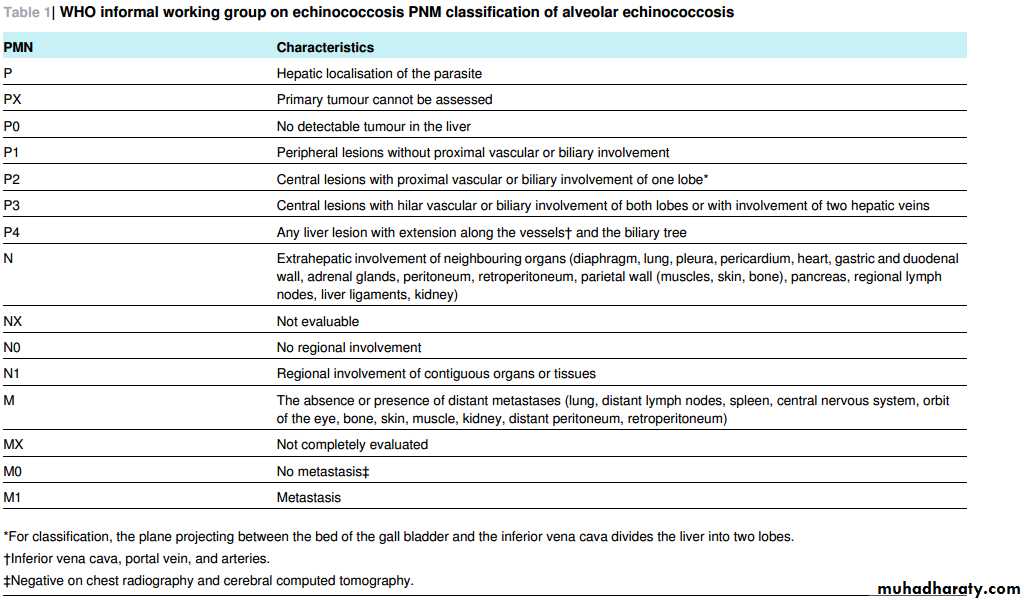

Ultrasound is the main diagnostic test for AE in the abdomen, and the imaging based WHO-IWGE PNM classification system (table 1⇓; fig 5⇓) is the recognised benchmark for standardised evaluation of diagnosis and treatment.

As with CE, serodiagnosis of AE is used as an adjunct to other detection procedures.

Conventional PCR can detect E multilocularis specific nucleic acids in tissue biopsies and real time PCR can be used to assess viability.

Notably, however, for both diseases a negative real time PCR result does not reflect complete parasite inactivity and a negative PCR cannot rule out disease.

How is CE treated and managed?

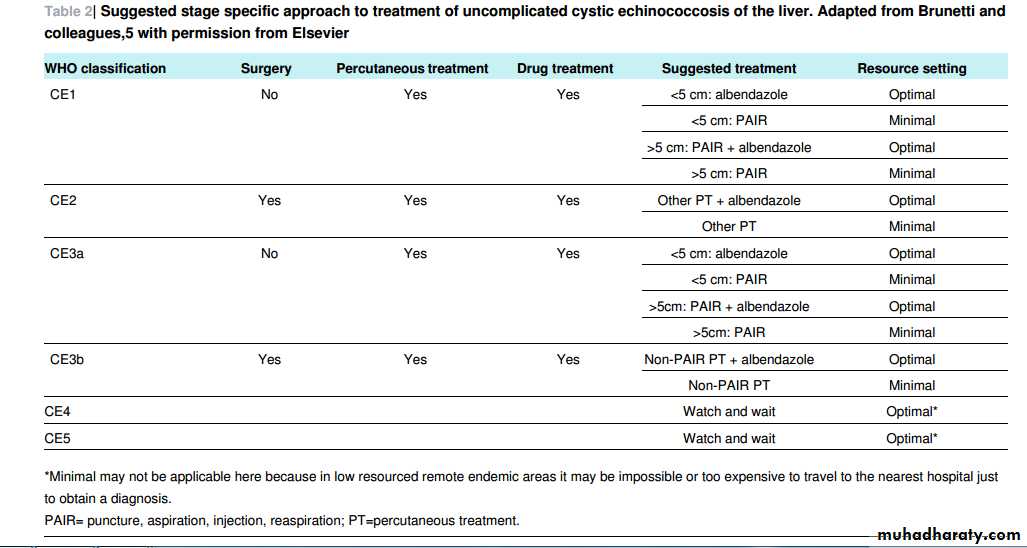

The WHO-IWGE classification providesthe basisfor choosing basically four treatment and management options for CE:surgery, percutaneous sterilisation, drug treatment, and observation (watch and wait).

However, there is no optimum treatment for CE and no clinical trials have compared the different modalities.

Table 2⇓ shows the current expert

consensus on the management of liver CE.

Surgery

Surgery is the classic treatment but, despite being curative, it does not totally prevent recurrence.Furthermore, in the absence ofspecific clinical trials, the evidence for the surgical treatment of complicated liver and disseminated CE islimited.

Surgery is, however, the choice for large or infected cysts, cysts likely to rupture, and cysts in important organ locations.

Surgery may not be practical for patients with multiple cysts in several organs.

Open cystectomy, pericystectomy, partial hepatectomy or lobectomy, cyst extrusion (Barrett’stechnique), and drainage of infected cysts are some of the surgical options available.

In cases where cyst resection is incomplete, or if small lesions remain undetected, disease can recur.

Postoperative fatality is about 2% but can be higher if additional surgery is needed or if medical facilities are inadequate.

Percutaneous sterilisation techniques

These include PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection,

reaspiration), which destroys the cyst’s germinal layer,

and modified catheterisation approaches, which evacuate the complete cyst.

PAIR, developed in the 1980s, involves ultrasound assisted percutaneous needle puncture aspiration of

the cyst, followed by injection of a suitable protoscolicide (such as 20% sodium chloride or 95% ethanol) and cyst reaspiration after 15-20 minutes.

Anaphylaxis is a risk.

Assess cyst fluid for protoscoleces and bilirubin, and, to minimise the risk of secondary CE, co-administer benzimidazole. CE2 and CE3b

stages (fig 4) are problematic because they have many compartments that require individual puncture, and these commonly relapse after PAIR.

Large bore catheters, combined with suitable aspiration equipment, may in future replace PAIR for these stages, but their true effectiveness needs to be established.

The choice of between surgery or percutaneous

sterilisation can be difficult. Comparison of the two procedures requires large carefully designed clinical studies, which have yet to be done.17combinations of anthelmintics (such as albendazole plus praziquantel) that have been used to treat CE is also needed.

Watch and wait

Leaving uncomplicated cyst types (CE4 and CE5) untreated and just monitoring them by imaging (particularly ultrasound) is a logical management option given that a proportion of cysts calcify over time and become completely inactive; such cysts do not compromise organ function or cause discomfort.Such an approach is attractive but requires systematic study to define fully its indications and limitations.

How is AE treated and managed?

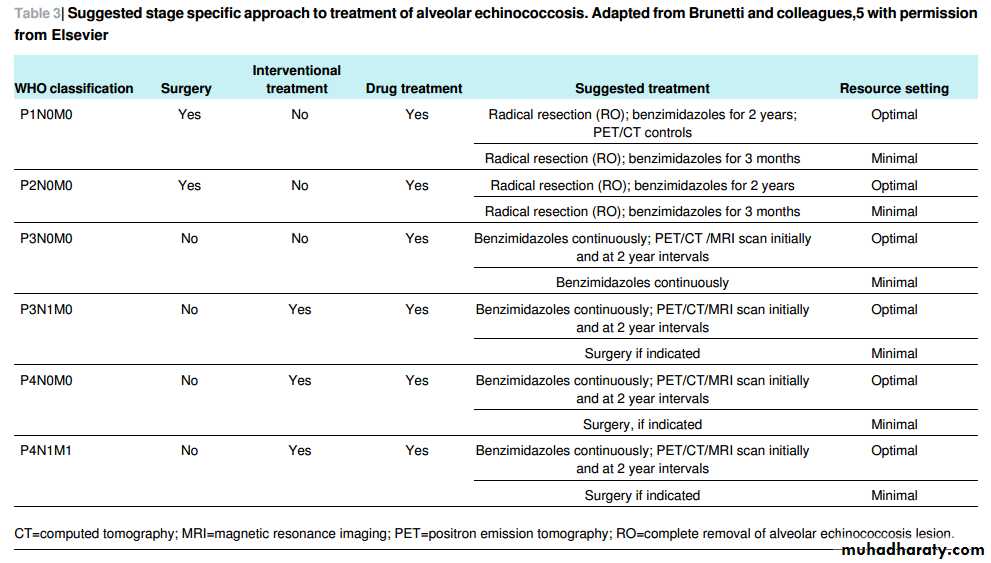

Table 3⇓ details a stage specific approach to treating AE.Historically, surgery has been the recommended treatment for early disease.

Early diagnosis reduces the need for radical surgery and results in fewer unresectable lesions.

Long term treatment with benzimidazoles is essential for patients with inoperable AE or after resection of E multilocularis lesions.

Benzimidazoles are parasitostatic—they inhibit larval

proliferation but do not kill metacestodes.

They should be given for a minimum of two years and patients monitored for at least 10 years for relapse.

Benzimidazoles are not recommended before surgery.

As for CE, the drugs are given orally with fat-rich meals (10-l5 mg/kg/day, in two doses),

although they have been given at a higher dose of 20 mg per kg per day for 4.5 years.

Continuous treatment with albendazole

is tolerated well, having been used for more than 20 years in some patients; intermittent use is not recommended.

Mebendazole, given at a dose of 40-50 mg per kg per day over three days with a fatty meal, is an alternative to albendazole.

Figure 6⇓ shows the effect of albendazole treatment on a P4 AE lesion. Neither praziquantel nor nitazoxanide is clinicallyeffective against AE.

Allotransplantation of the liver has been carried out in patients with end stage AE.

However, the essential use of immunosuppressive treatment can stimulate the proliferation of parasitic remnants in the lung or brain.

A long term prospective follow-up of patients with AE treated by palliative liver transplantation in the 1980s found that some patients survived for 20 years.

Ex vivo liver resection, followed by autotransplantation of AE-free lateral segments, may offer aradical approach to improving prognosis, but this procedure needs to be fully evaluated.

What are the future challenges?

Considerable recent progress has been made in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of echinococcosis, but challenges remain. Clinical trial data systematically evaluating existing treatments are not available and ideal treatment options are lacking. Treatment indicators are often complicated, being based on cyst characteristics, availability of medical and surgical expertise and equipment, and patient compliance in long term monitoring programmes.Comparable and standardised procedures and terminology need to be established by the medical fraternity.

PAIR should be undertaken only by experienced doctors and trained teams capable of managing anaphylactic shock.

PAIR needs to be studied systematically, via randomised controlled trials, to assess its efficacy compared with surgery and other available options for treatment of uncomplicated hepatic cysts.

Given recent concerns about the cost and treatment efficacy of the benzimidazoles, new drugs are needed to combat both AE

and CE. Strategies aimed at defining new compounds need to be pursued.

TheWHO-IWGE consensusrecommendationsforthe ultrasound imaging based classification of CE cysts need to be more wider disseminated to clinicians because they are useful when choosing treatment options.

Similarly, the WHO-IWGE classification

for AE should be advocated as the international classification because it can help determine whether an E multilocularislesion should be excised or otherwise treated, give some indications for improved prognosis, and help determine the best treatment

option for the individual patient.

The current clinical diagnosis of AE and CE relies mainly on the detection of parasite lesions by imaging methods, but the procedures are expensive and are generally not available in resource poor settings.

Furthermore, they are not useful for detecting the early stages of infection, which is a major disadvantage because earlier diagnosis results in more effective and successful treatment.

Serodiagnosis can play a role in early detection because specific anti-Echinococcus antibodies appear in the blood system four to eight weeks after infection. Most available immunodiagnostic techniques have been used in the diagnosis of echinococcosis.

However, most of these tests have not been systematically compared by independent laboratories, they are mainly used for research purposes, and few have found general acceptance by clinicians.

Summary points

Echinococcosis is a parasitic zoonosis caused by Echinococcus cestode wormsThe two major species of medical importance are Echinococcus granulosus and E multilocularis, which cause cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE), respectively

CE and especially AE are life threatening chronic diseases with a high fatality rate and poor prognosis if careful clinical management is

not carried out.

Human CE is cosmopolitan and the more common presentation, accounting for most of the estimated two to three million global

echinococcosis cases. AE has an extensive geographical range in the northern hemisphere.

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, imaging (radiology, ultrasonography, computed axial tomography, magnetic resonance imaging),

and serology.

Treatment options for CE are: surgery, percutaneous sterilisation, drugs, and observation (watch and wait). Surgery is the basis of treatment for early AE, but patients not suitable for surgery and those who have had surgical resection of parasite lesions must be treated with benzimidazoles (albendazole, mebendazole) for several years.

Key indicators for a positive diagnosis of echinococcosis

Medical historyHave you travelled to or emigrated from an endemic country (about five to 10 years ago)? If so, from where? (fig 1) Have you had contact with dogs, foxes, or livestock during the past five to 10 years?

Have you worked in a pastoral area where you may have had contact with wildlife during the past five to 10 years?

Have you worked in an abattoir during the past five to 10 years?

Cystic echinococcosis

Upper abdominal discomfortPoor appetite

Alveolar echinococcosis

Vague abdominal pain (right upper quadrant; 30% cases) (most cases originate in the liver)

Jaundice (25% cases)

Fatigue, weight loss, fever, chills

Physical examination

Cystic echinococcosis

On palpation of the abdomen a mass may be found on the surface of organs (the liver is affected in two thirds of patients); hepatomegaly

or abdominal distension may also be seen

Chest pain, cough, and haemoptysis can be indicative of cysts in the lung; cyst rupture into the bronchi may result in the expulsion of

hydatid material and cystic membranes

Cyst rupture can induce fever, urticaria, eosinophilia, and anaphylactic shock .Alveolar echinococcosis

On palpation of the abdomen, hepatomegaly may be detected Splenomegaly may be present in cases complicated by portal hypertension .Collateral circulation between the inferior and superior vena cava may be present on the skin in the thoracic and abdominal regions in advanced cases

Other physical symptoms are dictated by the location of metastatic legions (see lung involvement for cystic echinococcosis)

Laboratory investigations

General laboratory investigations show non-specific results Serology can help form a definitive diagnosis

Ultrasound guided fine needle biopsy can also be used to examine hydatid cyst fluid for the presence of protoscoleces or DNA using molecular techniques (polymerase chain reaction).

Radiology

Ultrasound (figs 4 and 5), computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging are the procedures of choice for the definitive diagnosis of echinococcosisImaging should be used to examine not only the liver but also the entire abdomen and thorax, and they are able to determine metastatic locations in alveolar echinococcosis

A patient’s perspective

I am a 31 year old farmer of the Hui minority from Ningxia, China. I was first admitted to hospital in May 2003 with extreme fatigue, cough,and difficulty breathing. A chest radiograph showed that my lungs were scattered with dark shadows and the doctors diagnosed me with aform of cancer and sent me home. In September 2003 a specialist doctor reviewed my case and asked me to come back to the hospital for further tests. The specialist doctor asked me many questions, performed a physical examination, and ran some tests including an ultrasound.

The ultrasound and blood test showed that I did not have cancer but had alveolar echinococcosis.

The parasite started in my liver and had spread to my lungs. I was given daily treatment with a drug called albendazole and after six months another chest radiograph showed that my lungs were clear and I felt much better. I was told to continue taking the drug to stop the parasite spreading from my liver to other organs.

Today I am still taking albendazole and am feeling well.

Zhang Yin Gui, Xiji County, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Peoples’ Republic of China

Tips for non-specialists

Refer symptomatic patients who travelled to, or emigrated from, an echinococcosis endemic area about five to 10 years ago, and had contact with dogs or wildlife, to an infectious disease physician

Serology provides supportive information for diagnosis but imaging studies provide the definitive diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is important because alveolar echinococcosis often presents with cancer-like symptoms

Imaging studies should examine the entire thorax and abdomen, not just the liver.

Treatment may involve the use of drugs (albendazole, mebendazole) or surgery (or both).

Fig 2 Life cycles of E granulosus and E multilocularis. Swallowed Echinococcus eggs hatch in the intestine to release oncospheres which pass through the gut wall and are carried in the blood system to various internal organs where they develop into hydatid cysts. E granulosus cysts are found mainly in the liver or lungs of humans and intermediate hosts.

Dogs and other canines, which act as definitive hosts for E granulosus, become infected by eating offal with fertile hydatid cysts containing larval protoscoleces. These larvae evaginate, attach to the canine gut, and develop into sexually mature adult parasites. Eggs and gravid proglottids are released in faeces. Humans are typically “dead end” hosts, but not always.

E multilocularis develops mainly in the liver of humans. Wild carnivores, such as the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and the arctic fox (Alopex lagopis) are the major definitive hosts for E multilocularis, with small mammals acting as intermediate hosts.

As with E granulosus, humans are exposed to E multilocularis eggs by handling infected definitive hosts or by eating contaminated food

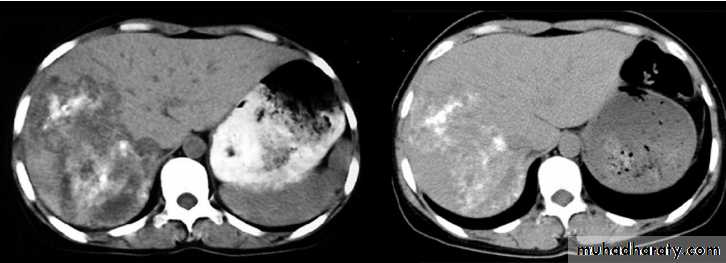

Computed tomography scan of the liver showing a large irregular AE lesion in the right lobe containing scattered

calcifications and liquefactions (left panel). After five years of treatment with albendazole, the lesion had not changed in

size but the areas of calcification had increased and those of liquefaction had decreased (right panel)