Management of venous thromboembolic diseases andthe role of thrombophilia testing: summary of NICEguidance

BMJ 27 June 2012

د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2012

Venous thromboembolic diseases range from asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) to fatal pulmonary embolism.

Non-fatal venous thromboembolic diseases may also cause serious long term conditions such as post-thrombotic syndrome or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

In the United Kingdom, pathways to diagnosis and to decisions on long term treatment or further investigation for thrombophilia and cancer vary, so guidance is needed in these areas. This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) on the management of confirmed or suspected venous thromboembolic diseases in adults (excluding pregnant women).

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations are based on the Guideline Development Group’s experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice. Evidence levels for the recommendations are given in italic in square brackets.Diagnostic investigations for deep venous thrombosis

If a patient presents with signs or symptoms of DVT,

conduct an assessment of his or her general medical history and a physical examination to exclude other causes.

[Basedon the experience and opinion of the Guideline

Development Group (GDG)]

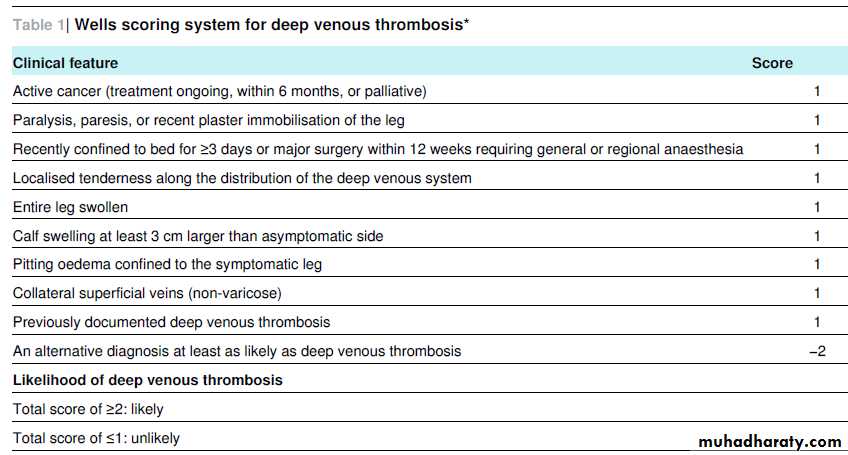

• For patients in whom DVT is suspected and who score ≥2

(“DVT likely”) on the Wells scoring system (table 1⇓),offer either (a) a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan to be done within four hours of being requested and, if the result is negative, a D dimer test; or (b) if a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan cannot be done within four hours, a Ddimer test and an interim 24 hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant, with a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan to be done within 24 hours of being requested.

Repeat the proximal leg vein ultrasound scan six to eight days later for all patients with a positive D dimer test and a negative proximal leg vein ultrasound scan.

[Based on very low to moderate quality evidence from meta-analysis of diagnostic

studies, individual diagnostic studies, and randomised

controlled trials and on a published cost effectiveness

analysis with potentially serious limitations and partial

applicability; the specific time points were based on the

GDG’s experience and opinion]

• For patients in whom DVT is suspected and who have a

Wells score of ≤1 (“DVT unlikely”) (table 1⇓), offer a Ddimer test. If the result is positive, offer either (a) a

proximal leg vein ultrasound scan to be done within four

hours of being requested; or (b) if a proximal leg vein

ultrasound scan cannot be done within four hours, an

interim 24 hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant, with a

proximal leg vein ultrasound scan to be done within 24

hours of being requested.

[Based on very low to moderate quality evidence from meta-analysis of diagnostic studies,

individual diagnostic studies, and randomised controlled trials, and on a published cost effectiveness analysis with potentially serious limitations and partial applicability;

the specific time points were based on GDG’s experience and opinion]

Diagnostic investigations for pulmonary embolism

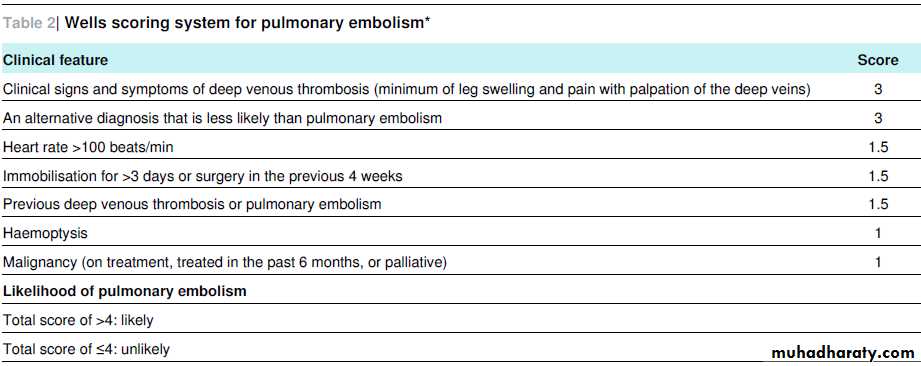

For patients in whom pulmonary embolism is suspected

and who have a Wells score of >4 (“pulmonary embolism likely”) (table 2⇓), offer immediate computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CT pulmonary angiography) or, if such imaging cannot be done immediately, offer immediate interim parenteral anticoagulant treatment followed by CT pulmonary angiography. Consider aproximal leg vein ultrasound scan if the CT pulmonary angiography is negative and DVT is suspected.

For patients in whom pulmonary embolism is suspected

and who have a Wells score of ≤4 (“pulmonary embolism unlikely”), offer a D dimer test. If the result is positive,offer either immediate CT pulmonary angiography or, if this imaging cannot be done immediately, offer immediate interim parenteral anticoagulant treatment followed by CT pulmonary angiography.[Both points above are based on very low to moderate quality evidence from diagnostic studies and randomised controlled trials and on an original economic model with potentially serious limitations and direct applicability]

Drug interventions for confirmed deep venous

thrombosis or pulmonary embolismOffer a choice of low molecular weight heparin or

fondaparinux, taking into account comorbidities,

contraindications, and drug costs, with the following

exceptions:

-For patients with severe renal impairment or established renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min/1.73 m2), offer unfractionated heparin with dose

adjustments based on the activated partial thromboplastin time, or low molecular weight heparin with dose adjustments based on an anti-factor Xa assay.

-For patients with an increased risk of bleeding, consider unfractionated heparin

-For patients with pulmonary embolism and haemodynamic instability, offer unfractionated heparin and consider thrombolysis.Start the low molecular weight heparin, fondaparinux, or unfractionated heparin as soon as possible and continue it for five days or until the international normalised ratio (adjusted by a vitamin K antagonist—see the next recommendation) is ≥2 for at least 24 hours, whichever is longer.

[Based on very low to moderate quality evidence from randomised controlled

trials and on cost effectiveness studies with potentially serious

limitations and partial applicability for the type of agent; the

other aspects were based on the GDG’s experience and opinion

and on information from marketing authorisation of products]

Offer low molecular weight heparin to patients with active cancer and confirmed proximal DVT or pulmonary embolism, and continue the heparin for six months. At six months, assess the risks and benefits of continuing anticoagulation. (From June 2012, not all low molecular weight heparins have a UK marketing authorisation for six months of treatment of DVT or pulmonary embolism in patients with cancer, and none of the anticoagulants has aUK marketing authorisation for treatment beyond six months.)

[Based on very low to moderate quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and on cost effectiveness studies with potentially serious limitations and partial applicability. The reassessment at six months is based on the GDG’s opinion]

Offer a vitamin K antagonist beyond three months to

patients whose pulmonary embolism is “unprovoked” (thatis, patients who have no antecedent major clinical risk

factor for venous thromboembolic disease and are not

taking hormonal therapy (oral contraception or hormone

replacement therapy), or patients with active cancer,

thrombophilia, or a family history of venous thromboembolic disease, because these are underlying risks that remain constant in patients). Take into account the patient’s risk of recurrence of venous thromboembolic disease and whether he or she is at increased risk of bleeding. Discuss with the patient the benefits and risks of extending their treatment with a vitamin K antagonist.

[Based on low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and on an original economic model with potentially serious limitations and partial applicability]

Consider extending the vitamin K antagonist beyond three

months for patients whose proximal DVT is unprovoked(same definition as for unprovoked pulmonary embolism) if their risk of recurrence of the disease is high and there is no additional risk of major bleeding. Discuss with the patient the benefits and risks of extending their treatment with a vitamin K antagonist. [Based on low to moderate quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and on an original economic model with potentially serious

limitations and partial applicability]

Thrombolysis for deep venous thrombosis

Consider catheter directed thrombolysis for patients with symptomatic iliofemoral DVT who have all of thefollowing: symptoms of less than 14 days’ duration, good

functional status, a life expectancy of one year or more,

and a low risk of bleeding.

[Based on very low to moderate quality randomised controlled trials; criteria for consideration in bullets are based on the GDG’s experience and opinion]

Mechanical interventions

Offer below-knee, graduated compression stockings with an ankle pressure greater than 23 mm Hg to patients with proximal DVT a week after diagnosis or when swelling is reduced sufficiently and there are no contraindications.

Advise patients to continue wearing the stockings for at

least two years; ensure that the stockings are replaced two or three times a year or according to the manufacturer’s instructions; and advise patients that stockings need to be worn only on the affected leg or legs.

[Based on moderate quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and asimple cost analysis; the specific details about pressure are based on the GDG’s experience and opinion]

Investigations for cancer

Offer all patients with unprovoked DVT or unprovoked pulmonary embolism who are not already known to have cancer the following investigations: a physical examination (guided by the patient’s full history), chest radiography,blood tests (full blood count, serum calcium, and liver

function tests), and urine analysis.

[Based on low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials]

Consider further investigations for cancer with an abdominopelvic CT scan (and mammography for women) in all patients aged over 40 years with a first unprovoked DVT or pulmonary embolism who do not have signs or symptoms of cancer based on the above initial assessment.[Based on low quality evidence from a randomised controlled trial and on a published cost effectiveness analysis with potentially serious limitations and partial

applicability]

Investigations for thrombophilia

Do not offer thrombophilia testing to patients who are continuing anticoagulation treatment, or to those who have had “provoked” DVT or pulmonary embolism (that is, patients who in the past three months have had a transient major clinical risk factor for venous thromboembolic disease)—for example, surgery, trauma, prolonged immobility (confined to bed, unable to walk unaided, or likely to spend a substantial proportion of the day in bed or in a chair), pregnancy, or puerperium—or patients who are having hormonal therapy (oral contraception or hormone replacement therapy)).• Consider testing for antiphospholipid antibodies in patientswho have had unprovoked DVT or pulmonary embolism if stopping anticoagulation treatment is planned.

• Consider testing for hereditary thrombophilia in patients who have had unprovoked DVT or pulmonary embolism and who have a first degree relative who has had DVT or pulmonary embolism if stopping anticoagulation treatment is planned.

• Do not routinely offer thrombophilia testing to first degree relatives of people with a history of DVT or pulmonary embolism and thrombophilia.

[All the above recommendations are based on the GDG’s experience and opinion]

Overcoming barriersAlthough it is important that the recommended key diagnostic tests are available when required, the Guideline Development Group recognises the potential difficulties and delays in accessing computed tomography pulmonary angiography,ventilation and perfusion scanning, or ultrasonography,especially at weekends and outside normal working hours.

It has therefore recommended interim anticoagulation and time limits for accessing these tests. The guideline also recommends catheter directed thrombolysis for some patients; relatively few such interventions are currently undertaken in the NHS, and there may be some resource implications for centres that do not

currently offer this treatment, requiring changes to facilities or local referral arrangements for appropriate patients.

Patients with cancer should be offered subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin instead of oral vitamin K antagonist, but patients who cannot self inject may need a carer or district nurse to administer these daily injections. Whenever possible, patients or carers should be trained in injection technique, to

limit the numbers needing nurse delivered injections, which would potentially increase costs. The recommendation to assess the risks and benefits of continuing treatment with a vitamin K antagonist at three months may also have clinical, resource,

and/or economic implications.

Factors associated with risk of recurrence after an unprovoked initial venous thromboembolic

event are debated; factors include male sex, post-thrombotic syndrome, obesity, and a raised D dimer after stopping anticoagulation. As there are no simple rules of thumb or validated tools to reliably predict these risks, the decisions will often have to be taken in a secondary care setting.