د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

MANAGEMENT OF END STAGEHEART FAILURE

Heart 2007Because of its age-dependent increase in incidence and prevalence, heart failure is one of the leading causes of death and hospitalisation among the elderly. As a consequence of the worldwide increase in life expectancy, and due to improvements in the treatment of heart failure in recent years, the proportion of patients that reach an advanced phase of the disease, so-called end stage, refractory or terminal heart failure, is steadily growing.

Patients with end stage heart failure fall into stage D of the ABCD classification of

the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA), and class III–IV of theNew York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification; they are characterised by advanced

structural heart disease and pronounced symptoms of heart failure at rest or upon minimal physical

exertion, despite maximal medical treatment according to current guidelines.

This patient population has a 1-year mortality rate of approximately 50% and requires special therapeutic

interventions.

Every attempt should be made to identify and correct reversible causes for aworsening of heart failure, such as poor patient compliance, myocardial ischaemia, tachy- or bradyarrhythmias, valvular regurgitation, pulmonary embolism, infection, or renal dysfunction. In

this article, we describe current strategies for the treatment of end stage heart failure.

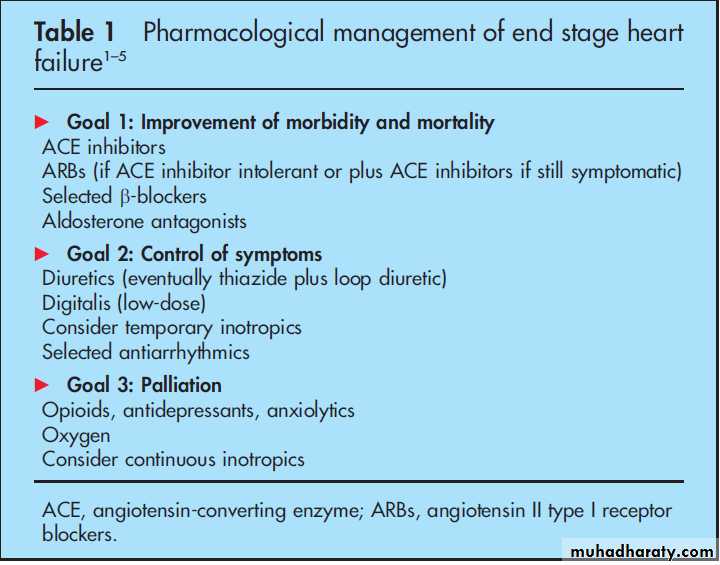

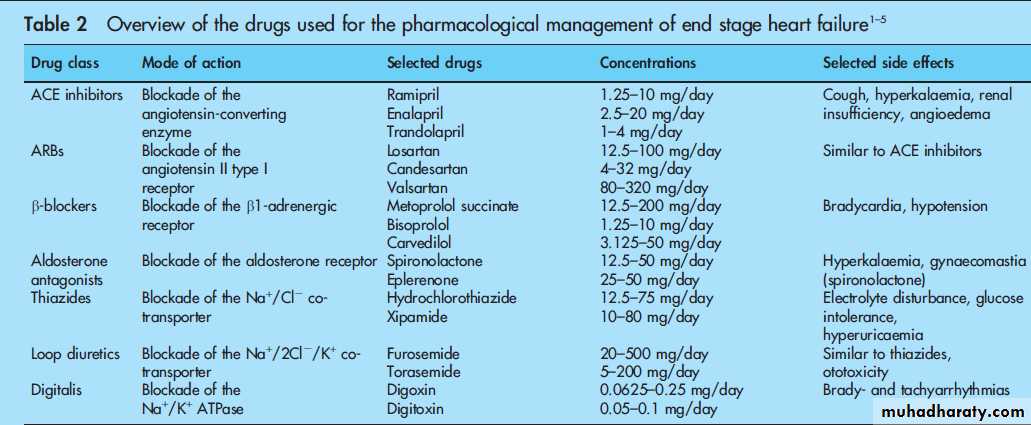

Current recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of heart failure patients with NYHA

class III–IV are summarised in table 1, while table 2 gives an overview of the drugs discussed in this

article. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are recommended as first-line treatment

in all patients with reduced left ventricular (LV) systolic function (ejection fraction (EF) (35–40%)

independent of clinical symptoms (NYHA I–IV), unless there are contraindications.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF END STAGE HEART FAILURE

In several large clinical heart failure trials ACE inhibitors have been shown to improve symptoms and functional capacity while decreasing the rate of hospitalisations and mortality.

Moreover, ACE inhibitors are indicated in patients who develop heart failure after the acute phase of myocardial infarction, and have been shown to improve survival and reduce reinfarctions and hospitalisations in this patient group.

ACE inhibitors should not be titrated based on symptomatic improvement but should be uptitrated to the target dosages shown to be effective in the large, placebo-controlled heart failure trials,

or to the maximal dose that is tolerated.

Treatment should be closely monitored by assessing blood pressure (supine and standing), renal function, and serum electrolytes (especially potassium) at regular intervals.

In patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure who do not tolerate ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II type I receptor blockers (ARBs) can be used as an alternative to improve morbidity and mortality.

In heart failure patients remaining symptomatic despite optimal medical treatment including ACE inhibitors, administration of ARBs on top of ACE inhibitors leads to an additive reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

However, the higher rate of hypotension, renal dysfunction, and hyperkalaemia with such a combination therapy warrants close monitoring of these parameters.

As patients with end stage heart failure frequently show signs of fluid retention or have a history of

such, inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system should be co-administered with diuretics, which

usually leads to rapid symptomatic improvement of dyspnoea and exercise tolerance while lacking

significant effects on survival.

End stage heart failure usually requires the use of loop diuretics, which may be effectively used in combination with thiazides in case of treatment refractory fluid overload due to a synergistic mechanism of action (sequential nephron blockade).

In addition to standard treatment with ACE inhibitors and diuretics, patients with symptomatic

stable systolic heart failure (NYHA II–IV) should be treated with b-adrenergic receptor blockers

unless there are contraindications. Results from several large clinical trials show that the

b-adrenergic receptor blockers carvedilol, bisoprolol, and metoprolol succinate decrease the rate of hospitalisations and mortality and lead to improvements of symptoms and functional class

(fig 1).

B-adrenergic receptor blocker treatment should be initiated in stable heart failure patients showing no

signs of fluid retention at very small doses, and up-titrated to the target doses used in the large clinical heart failure trials, or to the maximal dose that is tolerated. Patients should be closely monitored for evidence of heart failure symptoms, fluid

retention, hypotension, and bradycardia.

In patients with advanced heart failure (NYHA III–IV),

aldosterone receptor antagonists are recommended in addition to ACE inhibitors, b-adrenergic receptor blockers, and diuretics, unless contraindicated, and have been shown in the RALES andthe EPHESUS trials to improve survival and morbidity.

Treatment should be monitored by assessing serum potassium values, renal function, and fluid status, as well as gynaecomastia in the case of spironolactone.

Unless there are contraindications, cardiac glycosides are indicated for heart rate control in symptomatic heart failure patients (NYHA I–IV) with tachyarrhythmia due to atrial fibrillation (AF) already treated with adequate dosages of

b-blockers.

In that respect, a combination therapy of cardiac glycosides with b-adrenergic receptor blockers seems

to be more effective than either agent alone. In patients with systolic LV dysfunction (EF (35–40%) and sinus rhythm remaining symptomatic under treatment with ACE inhibitors,b-adrenergic receptor blockers, diuretics, and aldosterone receptor antagonists, additional treatment with cardiac glycosides at low serum concentrations (digoxin 0.5–0.8 ng/ml) may improve symptoms and reduce hospitalisations without having an effect on mortality.

Treatment should be monitored by assessing heart rate, atrioventricular conduction, and serum

values of potassium and the cardiac glycoside administered, as well as renal function in the case of digoxin, which in contrast to the primarily hepatically metabolised digitoxin is eliminated

by renal excretion.

Most supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias in heart failure patients can be effectively treated with the class III antiarrhythmic amiodarone, which may restore and maintain sinus rhythm or improve the success of electrical cardioversion

in heart failure patients with AF. Amiodarone treatment is neutral with respect to mortality and is not indicated for primary prophylaxis of ventricular arrhythmias.

Its benefits should be carefully weighed against potentially serious side effects including hyper- and hypothyroidism, corneal deposition, dermal photosensibility, hepatitis, and pulmonary fibrosis.

Dofetilide is a new class III antiarrhythmic without negative effects on mortality in heart failure patients, whose potential benefits should be weighed against an increased incidence of torsades de pointes tachycardias.

Anticoagulation is indicated in heart failure patients with AF, a previous thromboembolic

event, a mobile LV thrombus or following myocardial infarction.While repeated or prolonged treatment with positive inotropic agents such as b-adrenergic agonists (dobutamine) and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (milrinone, enoximone) increases mortality and is not recommended for the treatment of chronic

heart failure, intermittent intravenous inotropic treatment may be used in cases of severe cardiac decompensation with pulmonary congestion and peripheral hypoperfusion, or as abridge to heart transplantation. However, treatment-related

complications such as proarrhythmia or myocardial ischaemia may occur and the effect on prognosis is unclear. The new calcium sensitiser levosimendan has been shown to improve symptoms with fewer side effects than dobutamine in patients with severe low-output LV dysfunction. However, data

from the REVIVE-II and the SURVIVE studies presented at the AHA meeting in November 2005 were conflicting so that the definitive role of levosimendan in heart failure treatment needs to be further clarified.

For palliation of symptoms in patients with refractory end stage heart failure, data from a recently published study indicate that continuous outpatient support with inotropes may be an acceptable treatment option.

While there is no specific role for direct-acting vasodilators in the treatment of

systolic heart failure, a combination treatment of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate may improve symptoms and survival in heart failure patients intolerant of both ACE inhibitors and ARBs, as well as in an African-American subpopulation of heart

failure patients treated with ACE inhibitors and b-adrenergic receptor blockers.

In addition to baseline heart failure treatment, nitrates may improve angina and dyspnoea, and the

calcium antagonists amlodipine and felodipine may be used to treat refractory arterial hypertension and angina.

Opioids may be used to ameliorate symptoms in symptomatic patients with end stage heart failure in end-of-life situations where no further therapeutic options are available.

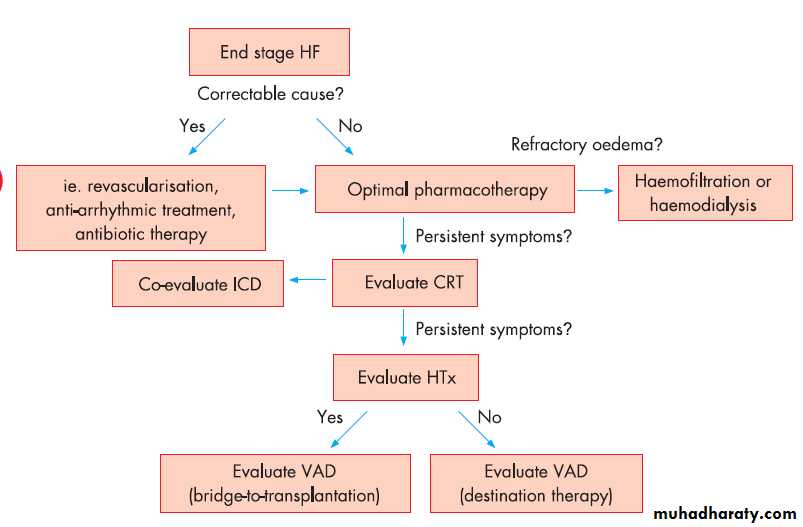

MECHANICAL AND SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF

END STAGE HEART FAILUREFig 1 presents a suggested algorithm for the treatment of patients with end stage heart failure. In patients with reduced LV function (EF (35%), sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block or echocardiographic signs of ventricular dyssynchrony and QRS width >120 ms, who remain symptomatic (NYHA III–IV) despite optimal medical treatment,

cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) using biventricular pacing improves symptoms and exercise capacity while decreasing hospitalisations and mortality.

In the COMPANION trial, heart failure patients in NYHA class III–IV with LVEF(35% and QRS width >120 ms were randomised to optimal pharmacological treatment alone or in combination with either CRT or CRT plus implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Importantly,while mortality was reduced in both device arms there was no significant difference in mortality between CRT and CRT/ICD. Therefore, currently available data indicate that the use of an ICD in combination with CRT should be based on the indications for ICD therapy.

For secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD), ICD implantation has been shown to reduce mortality in cardiac arrest survivors and in patients with sustained symptomatic ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

For primary prevention of SCD in heart failure patients with optimal pharmacological treatment, ICD therapy is indicated in selected patients with LVEF ≤ 30% after myocardial infarction (>40 days) and in patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic heart failure (NYHA class II–III) with LVEF ≤35% to reduce mortality.

Importantly, effectiveness of ICD therapy is time-dependent as there was no survival benefit following ICD

implantation until after the first year in the MADIT II and SCDHeFT trials. Thus, the decision for ICD implantation in stage D heart failure patients, which have a poor prognosis and ahigh frequency of ventricular arrhythmias, is particularly complex and must be made on an individual basis; this is especially so because of the possibility that ICD therapy might not alter total mortality but shift the mode of death from SCD to progressive haemodynamic failure and might impair the

quality of life by frequent shocks.

Importantly, ICDs or conventional pacemakers with right ventricular pacing have the potential for worsening of heart failure and LV function as

well as increasing hospitalisations. However, ICD therapy associated with CRT in patients with severe heart failure (NYHA class III–IV) with LVEF ≤35% and QRS duration >120 ms clearly improves morbidity and mortality.

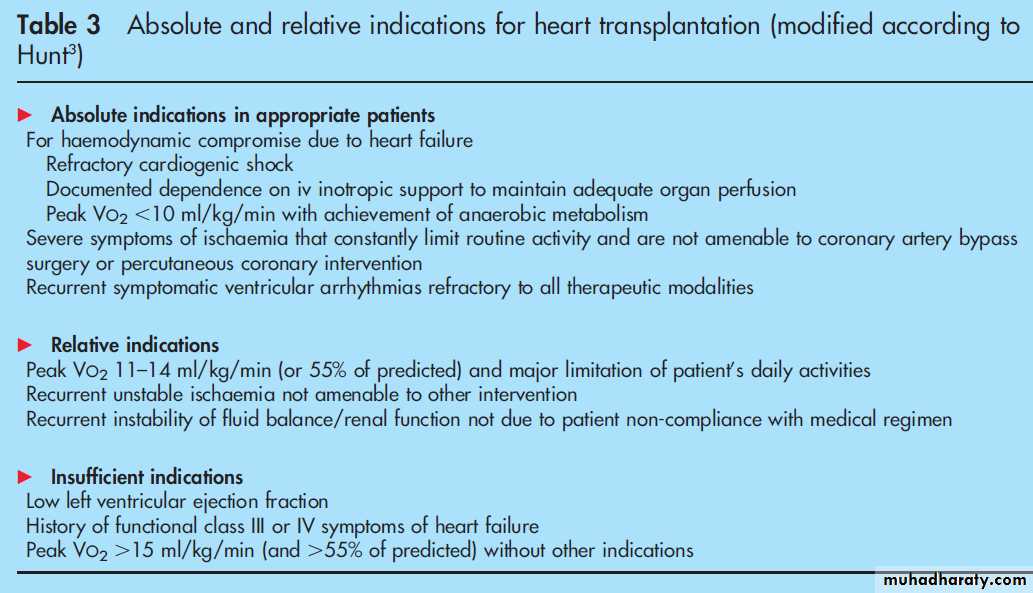

Heart transplantation is a firmly established surgical

approach for the treatment of end stage heart failure and has been shown to improve exercise capacity, quality of life, and survival compared with conventional treatment.Selection criteria for heart transplantation are presented in table 3 while contraindications include current drug or alcohol abuse, lack of compliance, serious uncontrollable mental disease, severe comorbidity (that is, treated malignancy with remission and < 5 years follow-up, systemic infection, significant renal or hepatic failure), and fixed pulmonary hypertension.

Cardiac allograft rejection is a significant problem during the first year after heart transplantation while the long-term prognosis is mainly limited by complications of immunosuppression (infections,

hypertension, renal failure, malignancies, and transplant

vasculopathy).

Overall, 5-year survival is 70–80% in heart transplantation patients receiving triple immunosuppressive therapy.

The availability of heart transplantation for patients who could benefit from the procedure is limited by the continuing shortage of donor hearts and the increasing number of transplant candidates.

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) can

provide short-term haemodynamic support.

In patients with end stage heart failure considered too unstable to await a suitable donor organ, biventricular or LV assist devices (LVAD) as well as total artificial hearts can be employed as bridge-to-transplantation

therapy and have been shown to improve quality of life,survival-to-transplantation rates, and post-transplant survival.

In patients with end stage heart failure who are ineligible for heart transplantation, a recently conducted landmark clinical trial has shown that implantation of an LVAD improves survival

and quality of life. These data have led to the use of

ventricular assist devices as an alternative to transplantation

so-called destination therapy.

Complications of assist devices

include infections, bleeding, thromboembolism, and device failure. In regard to the timing of assist device therapy, a recent report found that survival of patients undergoing bridge-totransplantationtherapy was best when assist devices were

implanted electively, as compared to implantations for urgent or emergency indications

In patients with end stage heart failure and volume overload refractory to diuretic treatment, haemofiltration or haemodialysis can provide temporary relief. In patients with severe LV systolic

dysfunction and significant secondary mitral regurgitation, observational studies indicate that mitral valve surgery may be associated with improvements in quality of life and survival.

LV aneurysmectomy is indicated in heart failure patients with large discrete LV aneurysms. According to current thinking, other surgical procedures such as cardiomyoplasty or partial ventriculotomy (Batista operation) are not indicated for the treatment of heart failure.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACHES

Early clinical studies in patients with heart failure have shown the feasibility of transfer of distinct stem and progenitor cell populations to the heart, and have demonstrated beneficial effects on cardiac function and/or tissue viability.However,due to small study sizes, lack of randomised control groups,poor understanding of the mechanisms of action of transplanted cells, lack of information on procedural issues (that is,optimal cell type, cell dosage, timing of cell transfer, optimal route of application), and safety concerns with some progenitors (such as the arrhythmogenicity associated with skeletal myoblast grafts), further basic research and the initiation of large, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trials with hard end-points (including mortality) are warranted before the role of cell-based therapy of heart failure can be judged.

Vasopressin receptor antagonists have been shown in

early studies to exert beneficial haemodynamic effects in patients with advanced heart failure; however, results from longer-term clinical trials underway to determine the role of vasopressin receptor antagonists in heart failure therapy have to be awaited.The new vasodilator agent nesiritide (recombinant

human brain natriuretic peptide) has recently been shown to improve symptoms in patients with acute heart failure without affecting clinical outcome; however, effects on morbidity and mortality are not clear from available clinical trials.

Ivabradine, a new selective inhibitor of the cardiac

pacemaker current If that lowers heart rate without negative inotropic effects, is currently being evaluated in a clinical phase III trial involving patients with stable coronary artery disease and systolic heart failure (the BEAUTIFUL study).

External ventricular restoration by surgical devices aiming at preventing further LV remodelling and reducing wall stress, such as the myosplint technique and the Acorn external cardiac support device, show promising early results; their relevance for heart

failure treatment is currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

PALLIATIVE APPROACHES

Before the condition of patients with end stage heart failure deteriorates so much that they can not actively participate in decisions, patients and their families should be educated about options for formulating and implementing advance directives and the role of palliative and hospice care services with reevaluationfor changing clinical status.

This may include indication of a preference for whether resuscitation should or should not be performed in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest, indication of which supportive care measures and interventions should be performed, and discussion of the option to inactivate ICDs at the end of life. In the final days of

life of heart failure patients with NYHA class IV, aggressive procedures such as intubation or ICD implantation that are not expected to result in clinical improvement are not appropriate.

For patients with end stage heart failure, it is important to ensure the continuity of medical care between inpatient and outpatient settings. Hospice care may provide options to relieve suffering from symptoms such as pain, dyspnoea, depression,

fear, and insomnia.

Treatment may include psychosocial support, the use of opiates, frequent or continuous administration

of intravenous diuretics, oxygen, continuous infusions

of positive inotropic agents, anxiolytics, and sleeping medications.

In caring for patients with end stage heart failure during

their final days, it may be particularly difficult for the patients, their families and the physicians to define the time point when the patient’s treatment goals shift from improving survival to improving quality of life, thus allowing for a peaceful and dignified death.

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

Treatment options for end stage heart failure have improved in recent years and include a combination of drugs, mechanical devices and surgical procedures which may improve symptoms and survival. Ultimately, the progressive course of heart failure leads to death and the treatment of end stage heart failure includes palliation. Future research into heart failure pathophysiology and therapeutic options is warranted.