د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

LONG TERM MEDICAL TREATMENT OFSTABLE CORONARY DISEASE

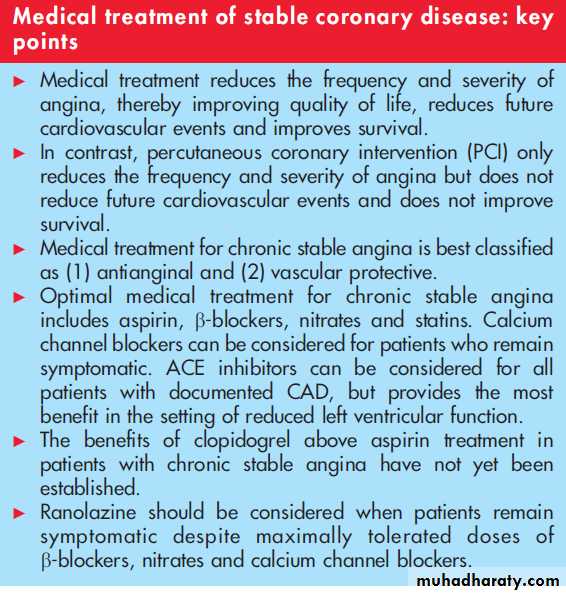

Heart 2007Chronic stable angina is a common manifestation of cardiovascular disease and represents afrequent problem encountered for medical practitioners. While percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is routinely performed in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD),medical treatment remains the cornerstone for long term treatment.

The goals of medical treatment

in patients with established CAD are to:• reduce the frequency and severity of angina, thereby improving the quality of life;

• reduce future cardiovascular events; and

• improve survival.

This review will specifically focus on the long term medical management of patients with chronic stable angina.

Medical treatment for chronic CAD is best classified as either

• Antianginal or

• Vascular protective.

Antianginal medications improve exercise duration until onset of angina, decrease the

severity and frequency of anginal episodes, and improve objective measures of ischaemia such as

time to onset of exercise induced ST segment depression. In contrast, vascular protective medications may reduce progression of atherosclerosis and potentially stabilise coronary plaques, thereby reducing future cardiovascular events.

Antianginal medications

b-blockersb-blockers should be first line treatment in patients with established CAD. For patients with a prior

history of myocardial infarction (MI), b-blockers reduce mortality by approximately 20%.

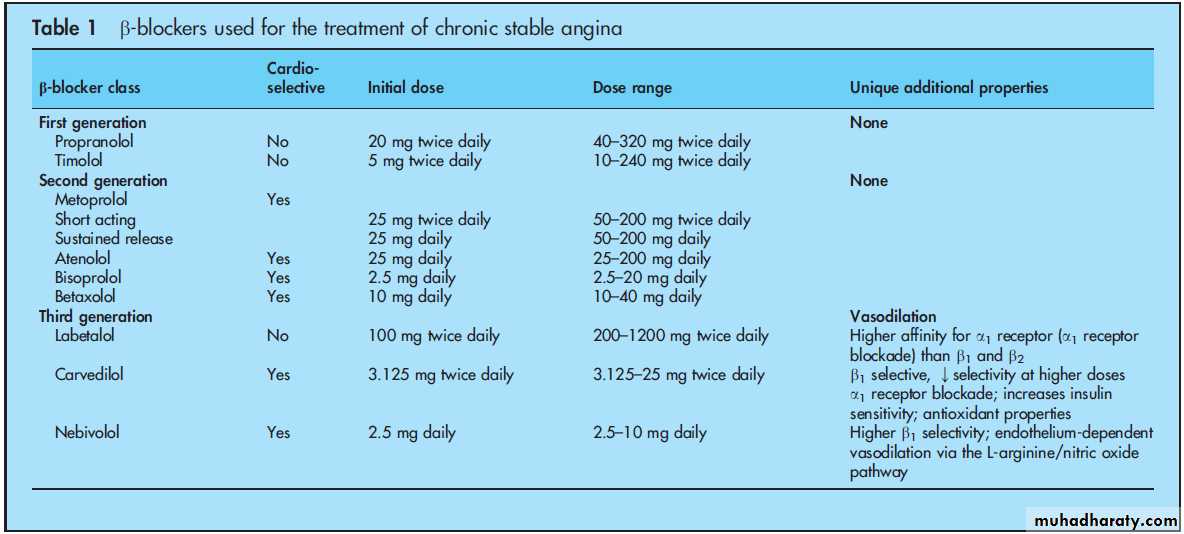

B-blockers are classified according to their ability to block the b1 and/or b2 receptors (referred to as cardiac selectivity) and the presence of additional pharmacodynamic properties (table 1).

Despite perceived contraindications such as reactive airway disease, peripheral vascular disease

and diabetes mellitus, cardioselective b-blockers are well tolerated in the majority of patients.

Absolute contraindications to b-blockers include severe bradycardia, advanced atrioventricular block,

decompensated congestive heart failure and severe reactive airway disease when airway support is

required. Even in the absence of perceived and absolute contraindications, the use of b-blockers in

patients with established CAD remains low.

In a large meta-analysis, b-blockers were found to have

similar efficacy to calcium channel blockers for angina relief, but were associated with fewer adverseevents. Potential side effects of b-blockers include impaired sexual function, reduced exercise

capacity, bradycardia and generalised fatigue.

In patients with stable angina who also manifest congestive heart failure symptoms with reduced

left systolic function, b-blockers are particularly beneficial and reduce heart failure related mortality

by approximately 35%.

Calcium channel blockers

In the early 1990s, several studies documented adverse cardiovascular events with several short

acting formulations of calcium channel blockers, which subsequently reduced the use of this class of

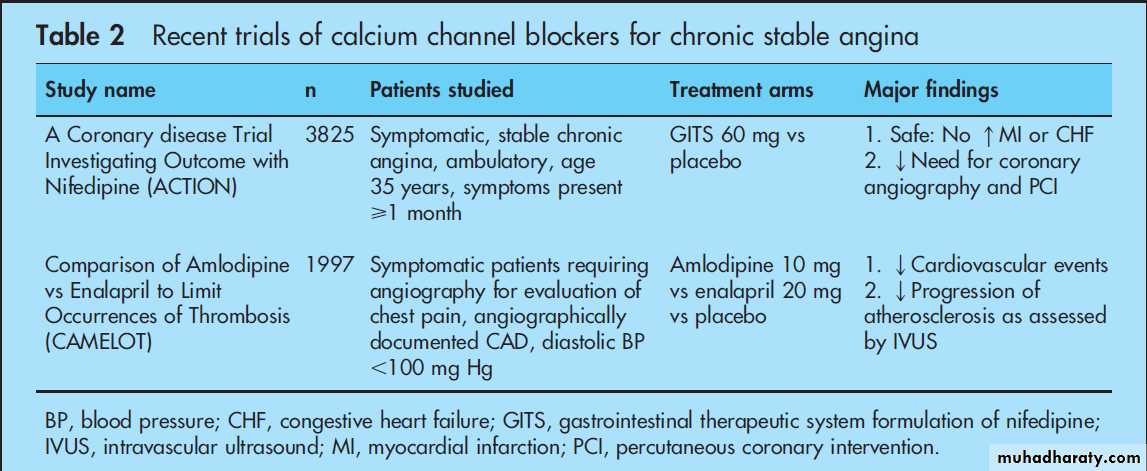

agents in patients with chronic stable angina. However, recent trials including ACTION (A Coronary disease Trial Investigating Outcome with Nifedipine) and CAMELOT (Comparison of Amlodipine versus Enalapril to Limit Occurrences of Thrombosis) have documented that calcium channel blockers are safe and beneficial in the treatment of CAD (table 2).

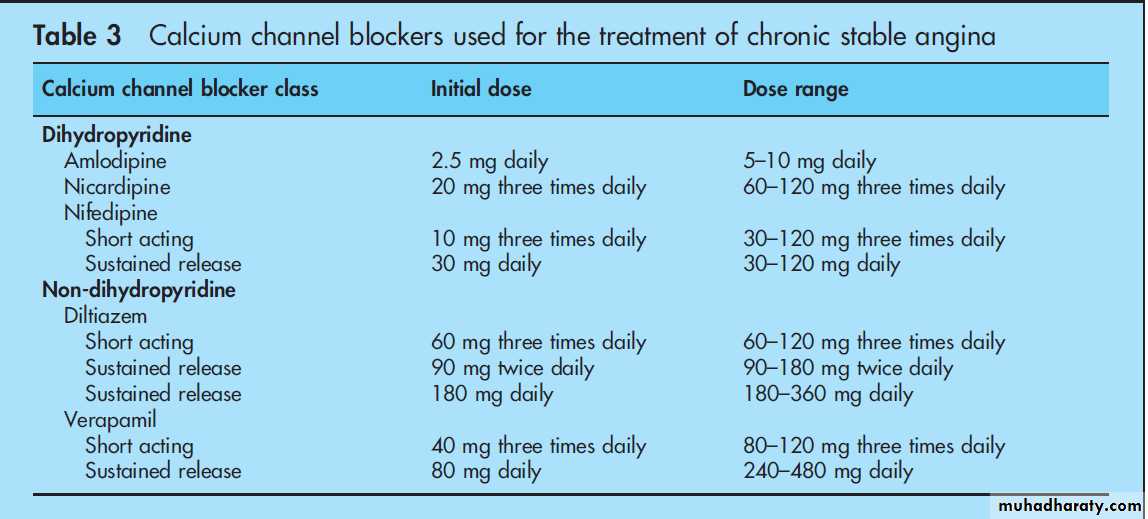

Calcium channel blockers are classified as dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine (table 3). For

patients with absolute contraindications to b-blockers, calcium channel blockers should be initiated

as first line treatment. When quality of life, preserved exercise capacity and normal sexual function

are the primary treatment goals, calcium channel blockers can be considered as preferred treatment over b-blockers.

For patients who remain symptomatic despite

optimal doses of b-blockers and nitrates, calcium channel blockers can be added with an acceptable safety profile.Potential side effects of calcium channel blockers include oedema, dizziness, headache and constipation. Bradycardia and heart block can occur in patients with significant conduction system disease. For patients with severe systolic dysfunction,

calcium channel blockers can worsen and/or precipitate congestive heart failure.

Nitrates

A variety of formulations of nitrate based medications exist,and choosing a specific delivery route (oral, ointment or transdermal patches) and specific agent is largely based on personal preference. Regardless of the agent and route used,patients requiring chronic nitrate treatment must be managed for nitrate tolerance, which is defined as the loss of the haemodynamic and antianginal effects that occurs during prolonged nitrate treatment.The only accepted method to prevent nitrate tolerance is to provide a ‘‘nitrate-free’’ period of

8–12 h every 24 h, which is most practically accomplished during sleep.

All patients with established CAD should carry

either a sublingual or a spray form of glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) for use during anginal events.

In an attempt to expedite care for cardiac patients, current guidelines advocate contacting emergency services for severe anginal episodes not relieved by one GTN dose.

A common problem in clinical practice involves use of

medications for erectile dysfunction such as sildenafil citrate (Viagra) when patients require nitrates for the relief and/or control of angina.

Sildenafil citrate relaxes vascular smooth muscle cells and potentiates the hypotensive effects of nitrates. Therefore, for patients using nitrates in any form, either on adaily basis or intermittently, sildenafil citrate is contraindicated.

Newer agents

Ranolazine is a novel antianginal agent that causes selective inhibition of the late sodium channel and was recently approved for the treatment of chronic stable angina. In the ERICA (Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina) trial, ranolazine reduced both the frequency of angina and the use of GTN in patients with continued angina despite the maximum dose of amlodipine (10 mg/day). Ranolazine should be considered in patients whom remain symptomatic despite optimal doses of b-blockers, calcium channel blockers and nitrates.Vascular protective medications

Aspirin

A meta-analysis including 2920 patients with stable angina by the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration found a 33% reduction in stroke, MI and vascular death with aspirin treatment.

The Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial found similar findings with a 34% reduction in MI and sudden death in 2035 patients with stable angina randomised to aspirin

75 mg daily or placebo. In the chronic setting, the appropriate dose of aspirin should be at least 75 mg per day.

Clopidogrel

While the use of clopidogrel is beneficial in patients withunstable angina and non-ST segment elevation MI (NSTEMI),its role in the long term management of patients with stable angina is less clear. The CAPRIE (Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events) trial studied patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease, including a subgroup with chronic stable angina, and found clopidogrel to be superior to aspirin alone in reducing the composite end point of stroke, MI or vascular death.

However, outcome events for the subgroup with chronic stable angina have not been published. The recently reported CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance) trial included a subgroup of patients with documented CAD and angina and found only apossible benefit of clopidogrel in reducing MI, stroke and cardiovascular death.

Given that the clinical benefit was small and bleeding events were increased, the routine use of clopidogrel in patients with chronic stable angina above aspirin treatment remains controversial.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

(ACE) inhibitors have been extensively studied in patients with CAD and various risk factor profiles. For those with preserved left ventricular function, ACE inhibitors reduce cardiovascular and all cause mortality by 17% and 13%, respectively. These findings translate into the need to treat 100 patients for approximately 4 years to prevent one cardiovascular event (death, non-fatal MI or coronary revascularisation procedure).In contrast, the recently reported PEACE (Prevention of Events with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibition) trial failed to show a benefit of the ACE inhibitor trandolapril in non-diabetic patients with known vasculardisease and normal left ventricular systolic function, possibly

related to an effect of combined statin treatment or suboptimal dosing. For patients with reduced left ventricular function, ACE inhibitors provide a more substantial benefit and reduce death or MI and all cause mortality by 23% and 20%, respectively.

Contraindications to ACE inhibitors include pregnancy, a

history of angioedema or anuric renal failure during previous exposure to an ACE inhibitor and severe hypotension. While the majority of patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency often tolerate ACE inhibitors well, a baseline serum creatinine >220 mmol/l >2.5mg/dl) should be considered a relative contraindication and requires close observation if an ACE inhibitor is initiated. The most common side effect of ACE inhibitors observed in clinical practice is a non-productive cough that occasionally requires discontinuation.HMG Co-A reductase inhibitors

The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A

(HMG Co-A) reductase inhibitors (statins) reduce future cardiovascular events including MI and death by approximately 25–30% in patients with established CAD. A review of multiple studies indicates that the benefits of statins are proportional to the level of low density lipoprotein (LDL) reduction—that is, lower

concentrations of LDL are associated with fewer cardiovascular events.

Although the optimal concentration of LDL cholesterol

remains a moving target, recent studies suggest agoal of <1.8 mmol/l (<70 mg/dl) in patients with chronic stable angina.Statins are generally well tolerated but require monitoring of liver enzymes at the initiation of treatment and with any change in dose. While a moderate elevation in liver enzymes (>3Xnormal) occurs in approximately 3% of patients treated with high dose statins, myositis and rhabdomyolysis are extremely rare side effects.

Dipyridamole

Although dipyridamole was occasionally prescribed for patients with chronic stable angina, there were little data to support this.Furthermore, because dipyridamole causes vasodilation in addition to its antithrombotic effects, routine use can enhance exercise induced myocardial ischaemia in patients with chronic stable angina.

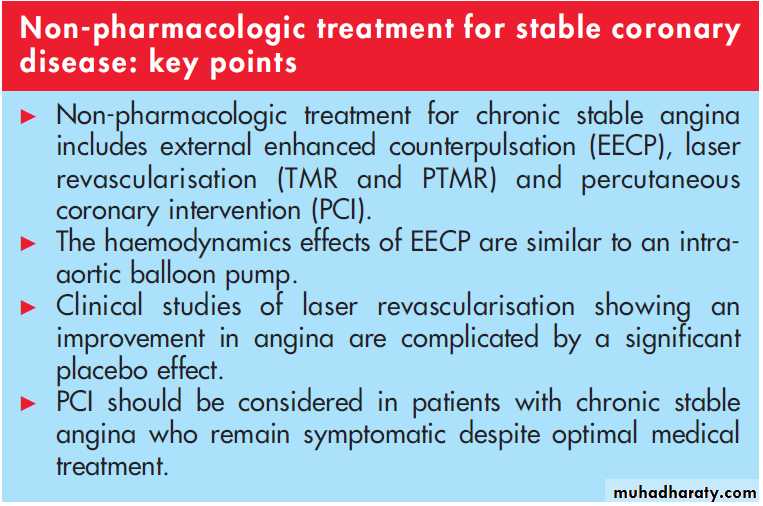

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

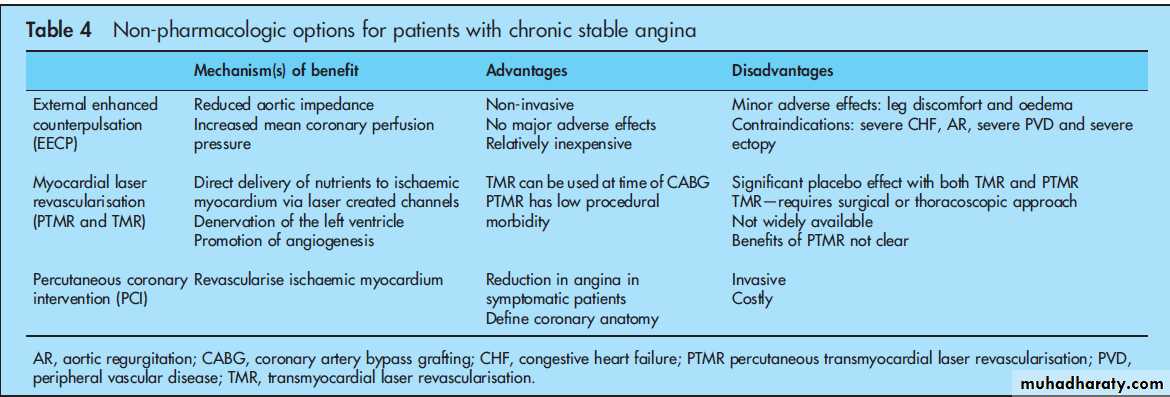

In addition to medical treatment, exercise, dietary modification and stress reduction should be applied in all patients.Additional therapeutic options in highly symptomatic patients on optimal medical treatment include external enhanced counter pulsation, transmyocardial laser revascularisation and PCI (table 4).

Exercise

While firm data are lacking, common recommendations for aerobic exercise training include three times per week of at least 20 min duration.

Dietary modification

A variety of diets have been proposed for patients with established CAD. While considerable debate exists regarding the ‘‘optimal’’ diet, widely accepted recommendations include adiet that promotes fruits, vegetables, grains, low fat dairy products, fish, poultry and lean meat with a saturated fat intake

of <10% and total cholesterol <200 mg/day.

External enhanced counterpulsation

External enhanced counterpulsation (EECP) is a non-invasive technique that uses three sets of pneumatic cuffs that are wrapped around the lower extremities and achieves haemodynamic effects similar to an intra-aortic balloon pump. Appropriate patients for EECP include those with angina refractory to maximal medical treatment when surgical and/or percutaneous revascularisation is not possible. Observational and randomised trials indicate that a majority of patients will achieve both an improvement in symptoms and exercise capacity that can persist for up to 2 years.Laser revascularisation

The thermal energy of laser beams can be used to create channels in the myocardium either surgically (transmyocardial laser revascularisation—TMR) or percutaneously (percutaneous transmyocardial laser revascularisation—PTMR). These channels are thought to deliver nutrients directly to ischaemic myocardium, but other suggested mechanisms include denervationof the left ventricle and promotion of angiogenesis.

While initial observational trials found a benefit for laser revascularisation, recent randomised trials suggest a significant placebo effect and no difference between medical treatment and laser revascularisation.

Percutaneous coronary intervention

PCI has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of angina, but does not reduce future cardiovascular events nor improve survival.In recent years there have been dramatic advances in the percutaneous management of CAD including

newer anticoagulants such as bivalirudin, drug eluting stents and closure devices.

The recently reported COURAGE

(Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) trial found that a strategy of PCI combined with aggressive medical treatment was not superior to medical treatment alone in patients with stable angina.PCI should therefore be reserved for patients who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

The long term medical management of patients with stable CAD includes the use of aspirin, b-blockers, nitrates and statins. Calcium channel blockers can be added if patients remain symptomatic, or used instead of b-blockers when quality of life issues (such as preserved exercise capacity) are the primary treatment goals. ACE inhibitors can be considered in patients with established CAD, but provide the most benefit in the setting of reduced left ventricular function. The novel agent ranolazine can be added to conventional treatment when patients remain symptomatic. PCI should be considered when angina limits quality of life.