د. حسين محمد جمعه

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

Drug treatment of supraventriculartachycardia

Heart 2009Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is characterised

by a rapid impulse formation, that emanates fromthe sinus node, from atrial tissue (focal or macroreentrant atrial tachycardia (AT)), from the (AV) node, or from anomalous muscle fibres that connect the atrium with the ventricle (accessory pathways (APs)).

(90%) encountered SVTs are AV nodal reentrant

tachycardia (AVNRT), mediated by accessory pathways, and atrial flutter (AFL).

The remaining SVTs are AT and nonparoxysmal,usually incessant, forms of SVT.

Paroxysmal forms of SVT (PSVT) are regular recurrent tachycardias with a sudden onset and termination.

If terminated by vagal manoeuvres, areentrant tachycardia involving the AV node is most likely.

The ventricular rate during SVT is between 140–250 beats/min (bpm).

If vagal or pharmacologic manoeuvres (adenosine)

during an SVT result in AV block with persistence

of atrial tachycardia, the diagnosis is most likely AT.

The A:V ratio is always 1:1 in AP mediated

tachycardias. Non-paroxysmal forms of SVT areongoing repetitive or permanent/incessant tachycardias, which if left untreated can result in

systolic left ventricular dysfunction and dilation

(tachycardiomyopathy).

GENERAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SVT

DiagnosisIn clinical decision making it is important to distinguish

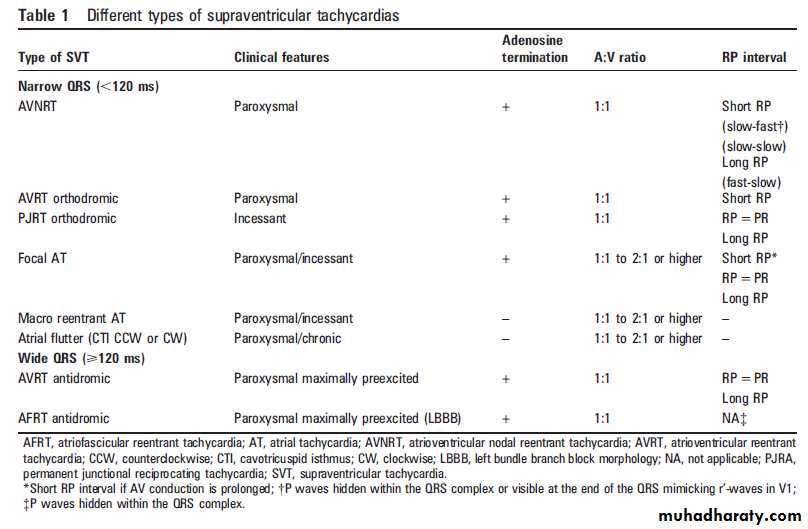

correctly between the different types of SVT.1 A

resting 12 lead ECG may disclose the presence of

preexcitation, prolongedQTinterval and other disease

states—such as old myocardial infarction, hypertrophy,

or bundle branch block—that may affect the

choice of therapy. An ECG during tachycardia may

give further clues to the type of SVT (table 1).

Focal ATs are due to triggered rhythms, abnormal

automaticity or microreentry activity from a discrete

atrial focus, the location of which governs the P wave

morphology. A long RP tachycardia with P waves

different from sinus and not compatible with retrograde

activation from the AV node supports focal AT.

A progressive acceleration during the first initiating

beats (‘‘warming up’’ phenomenon) and a progressive

decline in rate (‘‘cooling down’’) before termination

can be seen.

Macro-reentrant AT is a circus movement around an anatomical (scar, venous sites/mitral annulus) or functional barrier. AFL usually has a fast

regular atrial rate between 240–350 bpm without an

isoelectric baseline between atrial deflections. The

most common form is the right atrial cavotricuspid

isthmus (CTI) dependent AFL, with a counter clockwise activation around the annulus, resulting in predominantly negative (‘‘saw tooth’’ morphology) atrial waves (F waves) in the inferior leads, that are positive in V1.

In the uncommon clockwise form,

they are positivewith a terminal negative componentin the inferior leads. Non-CTI dependent flutter is

most often seen after corrective surgery for congenital heart disease or after atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation.

The F waves may be similar to those of CTI

dependent AFL or have very low amplitudes.

Multifocal AT is rare and is usually seen in elderly

adults with obstructive lung disease.

Sinus node reentry tachycardia (SNRT), which

originates from re-entrant circuits within or close

to the sinus node, is paroxysmal in nature and may

be terminated by vagal manoeuvres or adenosine.

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST), which usually

appears in women ,50 years of age, is an uncommon

form of sinus tachycardia characterised by a

persistent and excessive rate increase in response to

activity during daytime and rate normalisation at

night. The P wave morphology during both SNRT

and IST is identical to sinus rhythm.

The most common form of AVNRT (slow-fast)

utilises the slow pathway anterogradely and thefast pathway retrogradely. Less common are the

fast-slow AVNRT (reversed tachycardia circuit),

resulting in a long R-P tachycardia with negative P

waves in lead III and aVF before the QRS, and

intermediate forms (slow-slow AVNRT).

Associated structural heart disease is uncommon.

Accessory pathways that can conduct in the

antegrade direction to the ventricle are termed

‘‘manifest’’ (preexcitation on the resting ECG),

while those conducting retrogradely only are

known as ‘‘concealed’’ (no ventricular preexcitation

during sinus rhythm). A majority of the arrhythmias in patients with (WPW) syndrome are ‘‘orthodromic’’ tachycardias (antegrade conduction over the AV node–His bundle and retrograde over the AP)

and about 5% are ‘‘antidromic’’ tachycardias (reversed tachycardia circuit).

A potentially life threatening arrhythmia in patients with WPW is AF occurring over a pathway with short refractory period and rapid conduction to the ventricle. Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia (PJRT) is a less common form that involves retrograde conduction over a slowly conducting concealed pathway in the posteroseptal region, and which may cause atachycardiomyopathy.

In the rare Mahaim tachycardias

(antidromic AVRT with a left bundle branchblock (LBBB) configuration), the AP (frequently an

atriofascicular bundle) is an anomalous connection

from the free wall tricuspid annulus to the normal

right bundle branch or right ventricular myocardium.

A more detailed description of diagnostic

criteria is beyond the scope of this article.

Evaluation and management

The patient’s clinical history should clarify thepattern of the tachycardia in terms of type of

symptoms during SVT (palpitations, anxiety,

dyspnoea, fatigue, polyuria, chest pain, dizziness

or syncope), the frequency and duration of

episodes, mode of onset, possible triggers, the need

for hospitalisation, and restrictions of certain

sports or professions, which are all conditions that

affect the quality of life and thus govern the choice

and type of treatment..

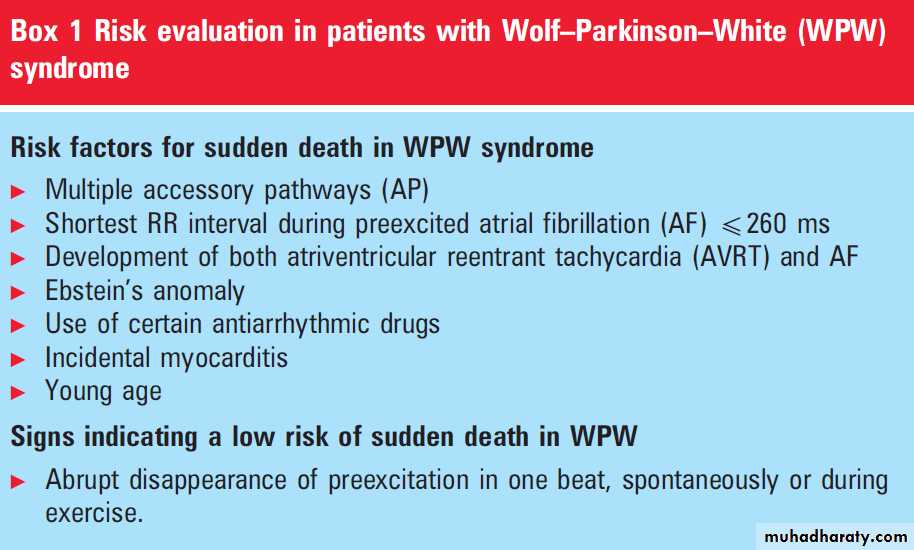

Although its natural historyis often benign in terms of survival, SVT can be potentially fatal in certain circumstances, which has important implications for choice of treatment Arrhythmias associated with APs in the WPW syndrome may be life threatening, related to preexcited AF degenerating into ventricular fibrillation due to fast AV conduction over an AP with ashort anterograde refractory period (box 1).3

Paroxysmal AFL, especially if the AV ratio is 1:1,

may cause acute heart failure in patients with left

ventricular dysfunction or in others syncope with a

fatal outcome.

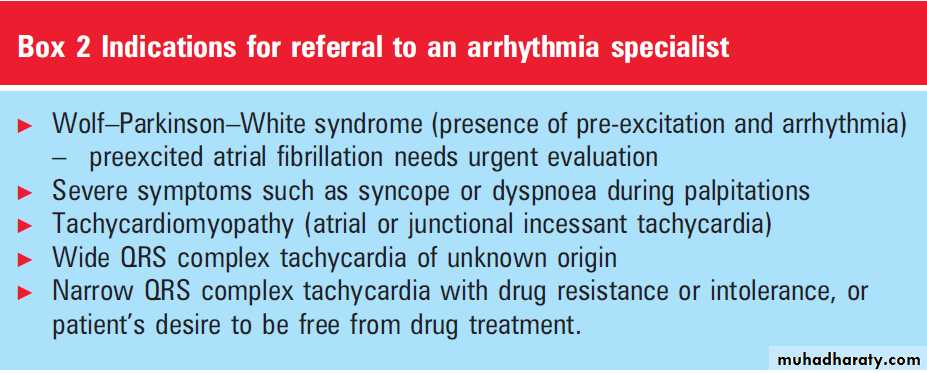

Patients with incessant tachycardias,such as the PJRT, may be asymptomatic at rest despite being in tachycardia, but may suffer from reduced exercise capacity or dyspnoea on exertion with mild to moderate systolic left ventricular dysfunction, leading to a primary diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy.4 In these conditions, catheter ablation is always the first

choice of treatment. Indications for referral to an

arrhythmia specialist are outlined in box .

If the arrhythmia is paroxysmal in nature and the arrhythmia mechanism is unknown, a bblocking

agent may be prescribed empirically.

Antiarrhythmic agents with class I or class III

properties should not be used without a documented

arrhythmia, due to the risk of pro-arrhythmia.

Electrophysiological studies are indicated in

patients with SVT who are candidates for catheter

ablation and also in those with disabling, undocumented attacks of sudden palpitations or those

with dilated cardiomyopathy in whom incessant

AT cannot be ruled out.

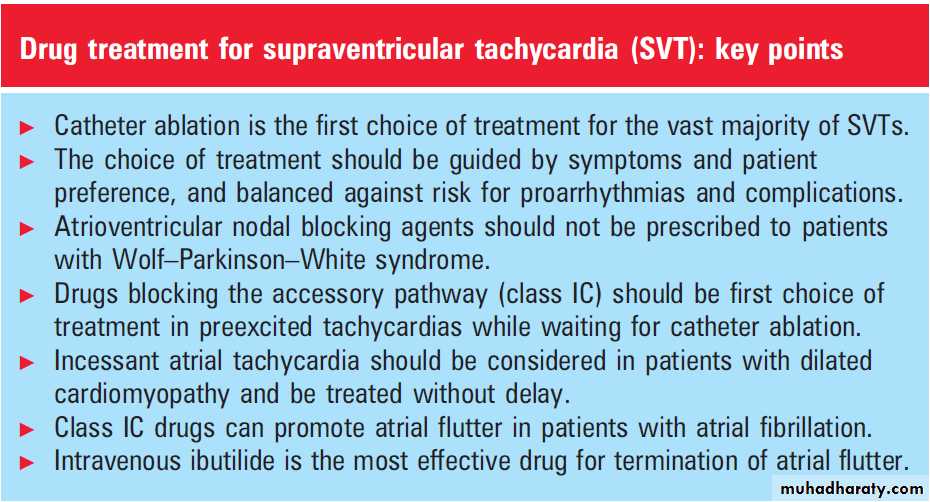

Long term treatment of most SVTs is predominantly

symptom driven. The choice between drugs

versus catheter ablation is based on patient preference and clinical judgment. Certain conditions

associated with increased risks, such as preexcited

tachycardias, incessant forms of tachycardias, signs

of left ventricular dysfunction (tachycardiomyopathy),

or aggravation of pre-existing cardiovascular

disease states, are all recommended for catheter

ablation as first choice.

Long term antiarrhythmic drug treatment is also discouraged in patients with infrequent symptomatic episodes and in women considering pregnancy. In the selection of drugs,associated cardiovascular disorders, renal and hepatic function, as well as age should be considered.

ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF SVT

Acute termination of narrow QRS complex tachycardias(in which AVNRT or orthodromic tachycardia is the most likely diagnosis) may be achieved by

vagal manoeuvres (carotid massage) and/or intravenous adenosine or verapamil, by inducing block in the anterograde slow AV nodal pathway.

Adenosine may precipitate AF with a rapid ventricular

rate in patients with preexcitation, in which

cases intravenous flecainide, propafenone, or procainamide may be used instead, if preferred.

Preexcited AF or tachycardias may be terminated

by intravenous procainamide, flecainide or ibutilide,or direct current (DC) shock cardioversion. AV

nodal acting drugs should not be used in patients

with preexcitated tachycardias. Immediate DC

cardioversion is the treatment of choice for all

haemodynamically unstable tachycardias.

The most effective drug for acute chemical cardioversion of AFL is ibutilide.

In recent prospective randomised studies the conversion rates of recent onset AFL was significantly superior with intravenous ibutilide compared with both amiodarone (87% vs 29%) (p,0.003) and intravenous procainamide (76% vs 14%). Ibutilide can also be used in patients on class IC antiarrhythmic drugs or amiodarone, since the incidence of torsades des pointes is as similar as in subjects without concomitant antiarrhythmic drug medication.

It should not be used in patients with left ventricular

dysfunction, prolonged QT interval, or underlyingsinus node disease, related to the risk for torsades des

pointes. Intravenous flecainide or propafenone may

slow the atrial rate and result in a paradoxical

increase in the ventricular response, and is therefore

not recommended for conversion of AFL.

Recurrent paroxysmal AFLs are usually terminated with DC cardioversion or atrial overdrive pacing.

For acute termination of AT, vagal manoeuvres or

adenosine (effective in 20–30%) or other AV nodal

blockers (b-blockers or calcium channel blockers)

may be tried. Adenosine usually terminates focal AT but not macro-reentrant AT.

These drugs are not effective in the case of paroxysmal repetitive runs of AT.

If adenosine fails, intravenous propafenone or

flecainide can be used, or amiodarone in the case ofsystolic left ventricular dysfunction. DC cardioversion

is often ineffective but may be considered if AT

persists despite the use of antiarrhythmic drugs.

Adenosine should not be used in patients with a

history of bronchospasm and should be used with

caution when the diagnosis is unclear because it may

produce ventricular fibrillation (VF) in patients with

coronary artery disease.

‘‘Pill in the pocket’’,

which refers to single dose treatment, may be considered for termination of infrequent, well tolerated but long lasting episodes of AVNRT, when self performed vagal manoeuvres alone are ineffective. A single oral dose of diltiazem (120 mg) plus propranolol (80 mg) was more effective in terminating PSVT than both placebo and flecainide (approximately 3 mg/kg).The approach is less effective in patients with concealed APs.

Patients should have normal left ventricular

function, no bradycardia and no pre-excitation, but it is not recommended in elderly people sincehypotension and sinus bradycardia are potential

complications.

PROPHYLACTIC ANTIARRHYTHMIC TREATMENT

OF SVT AVNRTCatheter ablation is recommended as the treatment

of choice after a first recurrence related to the high

success rate, low risk for AV block (,1%), and low

recurrence rate after ablation (,2%). Prophylactic

antiarrhythmic drug treatment is effective in

approximately 30–50%, and may burden the quality

of life more than the arrhythmia itself, if episodes are

infrequent.

In patients with recurrent episodes of AVNRT, unresponsive to AV nodal blocking agents,

and who prefer antiarrhythmic drug treatment, class IC drugs can be particularly effective due to their use dependent effect on the retrograde fast pathway.Flecainide (200–300 mg/day) prevented the recurrence

of AVNRT in 65% of patients and appears to

have greater long term efficacy than verapamil.

Several double blind, placebo controlled trials have

confirmed the efficacy of both flecainide and

propafenone for prevention of recurrences.

Limited prospective data are available for use of

class III drugs (for example, amiodarone, sotalol,dofetilide), even though many have been used

effectively to prevent recurrences. Toxicities,

including proarrhythmia, are of concern when used routinely .Amiodarone is an option in patients in whom all other treatment strategies have failed or cannot be used.

AVRT

The treatment of choice to prevent tachycardiarecurrences in WPW patients is catheter ablation,

which is successful in over 95% of cases and with a

low risk for adverse events depending on AP location.

Prophylactic antiarrhythmic drug treatment (propafenone,flecainide, sotalol, amiodarone) is justified

when awaiting such an ablation procedure or in

patients not accepting the procedure, if the patient is

Symptomatic with frequent and long lasting episodes.

A combination of a class 1C agent (propafenone or

flecainide) and a b-blocking agent is the most effective

drug regimen.

Class I antiarrhythmic drugs and amiodarone prolong the anterograde refractory period of the AP but have minor effect in the retrogradely conducting AP. The data on efficacy of sotalol are limited and no study has yet shown that amiodarone is superior to class Ic antiarrhythmic agents or sotalol. In a prospective study of azimilide, a novel class III agent, the time to recurrence of symptoms related to SVT did not differ significantly from the placebo group, indicating that azimilide did not confer a beneficial effect compared with placebo.

b-blocking agents have no effect on APs and their

ability to prevent tachycardia recurrences in patientswith the WPW syndrome is unknown.

Digitalis and calcium channel blocking agents (verapamil, diltiazem) may facilitate the development of VF during AF in patients with WPW syndrome, and should therefore not be used. Long term antiarrhythmic drug treatment is not recommended inWPWpatients with

high risk profiles (occupations or lifestyles), or in

those with severely symptomatic episodes.

The ablation of asymptomatic patients with a

WPW pattern is controversial and there is no rolefor antiarrhythmic drug treatment. Young patients

involved in sport or those with certain occupations

(pilots, divers) may be offered catheter ablation.

Tachycardia recurrences in patients with concealed

APs can be prevented with oral propafenone,

flecainide, or amiodarone in half of the cases,

although the latter is the agent of last resort when

a chronic pharmacological approach is preferred.

The treatment of choice for patients with Mahaim

AP is catheter ablation of the AP.

Atrial tachycardias .The treatment of choice for symptomatic recurrent, chronic and incessant AT is catheter ablation, the success rate of which depends on the type of AT.

Over 90% of focal AT can be successfully treated by

catheter ablation with ,8% of recurrences, in

experienced centres. Flecainide, propafenone, sotalol,and amiodarone may be used in patients who fail or refuse catheter ablation, even though their efficacy rate is low.

Catheter ablation should always be performed in

the case of systolic left ventricular dysfunction,which usually normalises within a few months

after abolishing the tachycardia. Macro-reentrant

ATs are rarely prevented by drugs such as

flecainide, propafenone, and amiodarone.

By slowing atrial conduction velocity, these drugs may

even facilitate the recurrences of macro-reentrantAT, whose atrial rate is then slower than in the

basal situation. Amiodarone with or without

verapamil or diltiazem may be used for rate control

to improve symptoms, and can be used in

symptomatic patients not amenable to ablation

or other drug treatment.

Catheter ablation of CTI dependant AFL has a high success rate (100%) and a low recurrence rate (,5%),and is the treatment of choice after the first episode or if the flutter is chronic. Inrandomised studies ablation was superior to conventional antiarrhythmic drug treatment in terms of maintaining sinus rhythm,quality of life, and lower need for rehospitalisation,even in patients aged 69 years.

Long term antiarrhythmic drug treatment isneeded in patients refusing an ablation procedure. Adequate rate control of AFL is frequently difficult to achieve withAVnodal blocking agents, if the AV nodal function is normal. Dofetilide reduces the AFL recurrence rate by 50% compared to

placebo.18 Dronedarone reduces the recurrence rates of AF orAFL, but data on effectiveness in each of the two arrhythmias are unclear. The efficacy of class Icdrugs is largely unknown.

By reducing atrial conduction velocity, these drugsmay facilitate the development of an AFL with relatively slow atrial rates (190–240 bpm), and eventually a life threatening 1:1 AV conduction during AFL. A ‘‘slow AFL’’ can also develop with amiodarone treatment, but due to the effects on theAVnode, theAVratio is usually>2:1.1 If CTI dependent AFL develops in patients with AF on class IC drugs or amiodarone (‘‘class IC AFL’’),ablation of the CTI may avoid AF recurrences in the majority of the cases.

The treatment of IST is predominantly symptom

driven. First choice is a b-blocking agentfollowed by verapamil and diltiazem. Catheter

ablation (sinus node modification) is associated

with poor long term success rates of approximately 66%. Patients with well tolerated SNRT that are controlled by vagal manoeuvres and/or drug treatment should not be considered for catheter ablation.

In SNRT and in some focal ATs, verapamil may prevent its recurrences. Catheter ablation, albeit generally successful, should be reserved for medically refractory cases.

Special forms of non-paroxysmal SVT Junctional incessant tachycardia (JET), which may occur during the first 6 months of life, is a narrow QRS complex tachycardia at rates of 140–300 bpm with AV dissociation and exceptionally with intermittent ventriculo-atrial (VA) conduction. It carries apoor prognosis with systolic left ventricular dysfunction,heart failure, and risk of death. Amiodarone is the drug of choice, if digoxin and propranolol in combination fails to reduce the rate below 150 bpm.