د. حسين محمد جمعة

اختصاصي الامراض الباطنةالبورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

CVS

It is the endocardial and subendocardial zones of the myocardial wall segment that are the least perfused regions of the heart and the most vulnerable to conditions of ischemia.

An older subclassification of MI, based on clinical diagnostic criteria, is determined by the presence or absence of Q waves on an electrocardiogram (ECG). However, the presence or absence of Q waves does not distinguish a transmural from a nontransmural MI as determined by pathology.

The distinction between STEMI and NSTEMI also does not distinguish a transmural from a nontransmural MI.

The presence of Q waves or ST-segment elevation is associated with higher early mortality and morbidity; however, the absence of these two findings does not confer better long-term mortality and morbidity.

The severity of an MI depends on three factors: the level of the occlusion in the coronary artery, the length of time of the occlusion, and the presence or absence of collateral circulation. Generally, the more proximal the coronary occlusion, the more extensive the amount of myocardium that will be at risk of necrosis. The larger the myocardial infarction, the greater the chance of death because of a mechanical complication or pump failure. The longer the period of vessel occlusion, the greater the chances of irreversible myocardial damage distal to the occlusion.

STEMI is usually the result of complete coronary occlusion after plaque rupture. This arises most often from a plaque that previously caused less than 50% occlusion of the lumen. NSTEMI is usually associated with greater plaque burden without complete occlusion.

This difference contributes to the increased early mortality seen in STEMI and the eventual equalization of mortality between STEMI and NSTEMI after 1 year.

An MI can occur at any time of the day, but most appear to be clustered around the early hours of the morning or are associated with demanding physical activity, or both. Approximately 50% of patients have some warning symptoms (angina pectoris or an anginal equivalent) before the infarct.

The use of aspirin has been shown to reduce mortality from MI. Aspirin in a dose of 325 mg should be administered immediately on recognition of MI signs and symptoms.4, 9 The nidus of an occlusive coronary thrombus is the adhesion of a small collection of activated platelets at the site of intimal disruption in an unstable atherosclerotic plaque. Aspirin irreversibly interferes with function of cyclooxygenase and inhibits the formation of thromboxane A2.

Within minutes, aspirin prevents additional platelet activation and interferes with platelet adhesion and cohesion. This effect benefits all patients with acute coronary syndromes, including those with amyocardial infarction. Aspirin alone has one of the greatest impacts on the reduction of MI mortality. Its beneficial effect is observed early in therapy and persists for years with continued use. The long-term benefit is sustained, even at doses as low as 75 mg/day.

Treatment MI

Supplemental OxygenOxygen should be administered to patients with symptoms or signs of pulmonary edema or with pulse oximetry less than 90% saturation. Arterial blood that is at its maximum oxygen-carrying capacity can potentially deliver oxygen to myocardium in jeopardy during an MI via collateral coronary circulation. The recommended duration of supplemental oxygen administration in a MI is 2 to 6 hours, longer if congestive heart failure occurs or arterial oxygen saturation is less than 90%. However, there are no published studies demonstrating that oxygen therapy reduces the mortality or morbidity of an MI.

Nitrates

Intravenous nitrates should be administered to patients with MI and congestive heart failure, persistent ischemia, hypertension, or large anterior wall MI.4Nitrates are metabolized to nitric oxide in the vascular endothelium. Nitric oxide relaxes vascular smooth muscle and dilates the blood vessel lumen. Vasodilatation reduces cardiac preload and afterload and decreases the myocardial oxygen requirements needed for circulation at a fixed flow rate. Vasodilatation of the coronary arteries improves blood flow through the partially obstructed vessels as well as through collateral vessels. Nitrates can reverse the vasoconstriction associated with thrombosis and coronary occlusion.When administered sublingually or intravenously, nitroglycerin has a rapid onset of action. Clinical trial data have supported the initial use of nitroglycerin for up to 48 hours in MI. There is little evidence that nitroglycerin provides substantive benefit as long-term post-MI therapy, except when severe pump dysfunction or residual ischemia is present.4

Low BP, headache, and tachyphylaxis limit the use of nitroglycerin. Nitrate tolerance can be overcome by increasing the dose or by providing a daily nitrate-free interval of 8 to 12 hours. Nitrates must be avoided in patients who have taken a phosphodiesterase inhibitor within the previous 24 hours.

Pain Control

Pain from MI is often intense and requires prompt and adequate analgesia. The agent of choice is morphine sulfate, given initially IV at 5 to 15 minute intervals at typical doses of 2 to 4 mg.4 Reduction in myocardial ischemia also serves to reduce pain, so oxygen therapy, nitrates, and beta blockers remain the mainstay of therapy. Because morphine can mask ongoing ischemic symptoms, it should be reserved for patients being sent for coronary angiography. This was downgraded to a IIa recommendation in the latest STEMI guidelines.Beta Blockers

Beta blocker therapy is recommended within 12 hours of MI symptoms and is continued indefinitely.4, 9 Treatment with a beta blocker

decreases the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias, recurrent ischemia, reinfarction, and, if given early enough, infarct size and short-term mortality. Beta blockade decreases the rate and force of myocardial contraction and decreases overall myocardial oxygen demand. In the setting of reduced oxygen supply in MI, the reduction in oxygen demand provided by beta blockade can minimize myocardial injury and death

Unfractionated Heparin

Unfractionated heparin is beneficial until the inciting thrombotic cause (ruptured plaque) has completely resolved or healed. Unfractionated heparin has been shown to be effective when administered intravenously or subcutaneously according to specific guidelines. The minimum duration of heparin therapy after MI is generally 48 hours, but it may be longer, depending on the individual clinical scenario. Heparin has the added benefit of preventing thrombus through a different mechanism than aspirinWarfarin

Warfarin is not routinely used after MI, but it does have a role in selected clinical settings. The latest guidelines recommend the use of warfarin for at least 3 months in patients with left ventricular aneurysm or thrombus, a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30%, or chronic atrial fibrillation.Fibrinolytics

Fibrinolytic therapy is indicated for patients who present with a STEMI within 12 hours of symptom onset without a contraindication. Absolute contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy include history of intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke or closed head injury within the past 3 months, presence of an intracranial malignancy, signs of an aortic dissection, or active bleeding. Fibrinolytic therapy is primarily used at facilities without access to an experienced interventionalist within 90 minutes of presentation.As a class, the plasminogen activators have been shown to restore normal coronary blood flow in 50% to 60% of STEMI patients. The successful use of fibrinolytic agents provides a definite survival benefit that is maintained for years. The most critical variable in achieving successful fibrinolysis is time from symptom onset to drug administration. A fibrinolytic is most effective within the first hour of symptom onset and when the door-to-needle time is 30 minutes or less.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

should be used in all patients with a STEMI without contraindications. ACE inhibitors are also recommended in patients with NSTEMI who have diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, or an ejection fraction less than 40%. In such patients, an ACE inhibitor should be administered within 24 hours of admission and continued indefinitely. Further evidence has shown that the benefit of ACE inhibitor therapy can likely be extended to all patients with an MI and should be started before discharge.4, 9 Contraindications to ACE inhibitor use include hypotension and declining renal function.ACE inhibitors decrease myocardial afterload through vasodilatation. One effective strategy for instituting an ACE inhibitor is to start with a low-dose, short-acting agent and titrate the dose upward toward a stable target maintenance dose at 24 to 48 hours after symptom onset. Once a stable maintenance dose has been achieved, the short-acting agent can be continued or converted to an equivalent-dose long-acting agent to simplify dosing and encourage patient compliance. For patients intolerant of ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy may be considered.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Antagonists

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors on platelets bind to fibrinogen in the final common pathway of platelet aggregation. Antagonists to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors are potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during (PCI) and in patients with MI and acute coronary syndromes has been shown to reduce the composite end point of death, reinfarction, and the need to revascularize the target lesion at follow-up. The current guidelines recommend the use of a IIb/IIIa inhibitor for patients in whom PCI is planned. For high-risk patients with NSTEMI who do not undergo PCI, a IIb/IIIa inhibitor may be used for 48 to 72 hoursEvidence is less well established for the direct thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin. The 2007 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend bivalirudin as an alternative to heparin therapy for patients who cannot receive heparin for a variety of reasons (e.g., heparin-induced thrombocytopenia).

Statin Therapy

A statin should be started in all patients with a myocardial infarction without known intolerance or adverse reaction prior to hospital discharge. Preferably, a statin would be started as soon as a patient is stabilized after presentation. The Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIMI 22) trial suggested a benefit of starting patients on high-dose therapy from the start (e.g., atorvastatin 80 mg/day).Aldosterone Antagonists

In the Epleronone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) trial, a mortality benefit was seen with eplerenone administration in all post-MI patients, provided multiple criteria were met. The criteria included concomitant use of an ACE inhibitor, ejection fraction less than 40%, symptomatic heart failure or diabetes, a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, and a potassium level less than 5 mEq/dLIn patients that meet these criteria, the use of eplerenone has a Class I indication.

Other Treatment Options

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionPatients with STEMI or MI with new left bundle branch block should have PCI within 90 minutes of arrival at the hospital if skilled cardiac catheterization services are available.9

Patients with NSTEMI and high-risk features such as elevated cardiac enzymes, ST-segment depression, recurrent angina, hemodynamic instability, sustained ventricular tachycardia, diabetes, prior PCI, or bypass

are recommended to undergo early PCI (<48 hours).

PCI consists of diagnostic angiography combined with angioplasty and, usually, stenting.

It is well established that emergency PCI is more effective than fibrinolytic therapy in centers in which PCI can be performed by experienced personnel in a timely fashion.14 An operator is considered experienced with more than 75 interventional procedures per year. A well-equipped catheterization laboratory with experienced personnel performs more than 200 interventional procedures per year and has surgical backup available. Centers that are unable to provide such support should consider administering fibrinolytic therapy as their primary MI treatment.

As a class, the plasminogen activators have been shown to restore normal coronary blood flow in 50% to 60% of STEMI patients. PCI can successfully restore coronary blood flow in 90% to 95% of MI patients. Several studies have demonstrated that PCI has an advantage over fibrinolysis with respect to short-term mortality, bleeding rates, and reinfarction rates. However, the short-term mortality advantage is not durable, and PCI and fibrinolysis appear to yield similar survival rates over the long term.

PCI provides a definite survival advantage over fibrinolysis for MI patients who are in cardiogenic shock. The use of stents with PCI for MI is superior to the use of PCI without stents, primarily because

stenting reduces the need for subsequent target vessel revascularization(restoration of blood supply).

Surgical Revascularization

Emergent or urgent (CABG) is warranted in the setting of failed PCI in patients with hemodynamic instability and coronary anatomy amenable to surgical grafting.9 also indicated in the setting of mechanical complications of MI, such as ventricular septal defect, free wall rupture, or acute mitral regurgitation.

CABG can limit myocardial injury if performed within 2 or 3 hours of symptom onset. Emergency CABG carries a higher risk of perioperative morbidity (bleeding and MI extension) and mortality than elective CABG. Elective CABG improves survival in post-MI patients who have left main artery disease, three-vessel disease, or two-vessel disease not amenable to PCI.

Implantable Cardiac Defibrillators

The trials demonstrated a 31% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality with the prophylactic use of an ICD in post-MI patients with depressed ejection fractions.16 The current guidelines recommend waiting 40 days after an MI to evaluate the need for ICD implantation. ICD implantation is appropriate for patients in NYHA functional class II or III with an ejection fraction less than 35%. For patients in NYHA functional class I, the ejection fraction should be less than 30% before considering ICD placement. ICDs are not recommended while patients are in NYHA functional class IVStress testing is not recommended within several days after a myocardial infarction. Only submaximal stress tests should be performed in stable patients 4 to 7 days after an MI. Symptom-limited stress tests are recommended 14 to 21 days after an MI. Imaging modalities can be added to stress testing in patients whose electrocardiographic response to exercise is inadequate to confidently assess for ischemia (e.g., complete left bundle branch block, paced rhythm, accessory pathway, left ventricular hypertrophy, digitalis use, and resting ST-segment abnormalities).

From a prognostic standpoint, an inability to exercise and exercise-induced ST-segment depression are associated with higher cardiac morbidity and mortality compared with patients able to exercise and without ST-segment depression.4Exercise testing identifies patients with residual ischemia for additional efforts at revascularization.

Exercise testing also provides prognostic information and acts as a guide for post-MI exercise prescription and cardiac rehabilitation.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease and MI. For patients who have undergone an MI, smoking cessation is essential to recovery, long-term health, and prevention of reinfarction. In one study, the risk of recurrent MI decreased by 50% after 1 year of smoking cessation.18 All STEMI and NSTEMI patients with a history of smoking should be advised to quit and offered smoking cessation resources, including nicotine replacement therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and referral to behavioral counseling or support groups.Long-Term Medications

Most oral medications instituted in the hospital at the time of MI will be continued long term. Therapy with aspirin and beta blockade is continued indefinitely in all patients. ACE inhibitors are continued indefinitely in patients with congestive heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension, or diabetes.4, 9 A lipid-lowering agent, specifically a statin, in addition to diet modification, is continued indefinitely as well. Post-MI patients with diabetes should have tight glycemic control according to earlier studies. The latest ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a goal HbA1c of less than 7%.Cardiac Rehabilitation

provides a venue for continued education, reinforcement of lifestyle modification, and adherence to a comprehensive prescription of therapies for recovery from MI including exercise training. Participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs after MI is associated with decreases in subsequent cardiac morbidity and mortality. Other benefits include improvements in quality of life, functional capacity, and social support. However, only a minority of post-MI patients actually participate in formal cardiac rehabilitation programs because of several factors, including lack of structured programs, physician referrals, low patient motivation, noncompliance, and financial constraints.Association between C reactive protein and coronary heart disease: mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data

• BMJ 2011; 342

What is already known on this topic

Blood concentrations of C reactive protein are strongly and continuously associated with future risk of coronary heart disease, though it is unknown whether this correlation reflects cause and effect .Genetic variants related to C reactive protein can be used as proxies for C reactive protein concentration to help judge causality (“mendelian randomisation analyses”).Previous studies have been insufficiently powerful and detailed to evaluate the possibility of any moderate causal role for C reactive protein in coronary heart diseaseWhat this study adds

With individual data from almost 200 000 people (including almost 47 000 with coronary heart disease), has shown that genetically raised concentration of C reactive protein is unrelated to conventional risk factors and risk of coronary heart disease.Human genetic data indicate that C reactive protein concentration itself is unlikely to be even a modest causal factor in coronary heart disease

Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of adverse cardiovascular

events in aspirin treated patients with first time myocardialinfarction: nationwide propensity score matched study

BMJ 2011;342

RESEARCH

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Guidelines recommend dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel after myocardial infarction.The possible interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is widely debated.Evidence from recent ex vivo studies suggests that proton pump inhibitors may reduce the platelet inhibitory effect of aspirin in patients with cardiovascular disease

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this study of a large unselected nationwide cohort of aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction, use of proton pump inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events

Conclusions

In this study of a large unselected nationwide population we found that use of proton pump inhibitors in aspirin treated patients with first time myocardial infarction was associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events.

The increased risk was not observed in patients treated with H2 receptor blockers.

It is unlikely, but not impossible, that the

increased cardiovascular risk associated with concomitant use of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors is caused by unmeasured confounders.

Focus on this area, including the implication of this study for the discussion on clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is warranted owing to the large clinical implications of apossible interaction between proton pump inhibitors and aspirin.

Randomised prospective studies as well as observational studies based on other populations are needed.

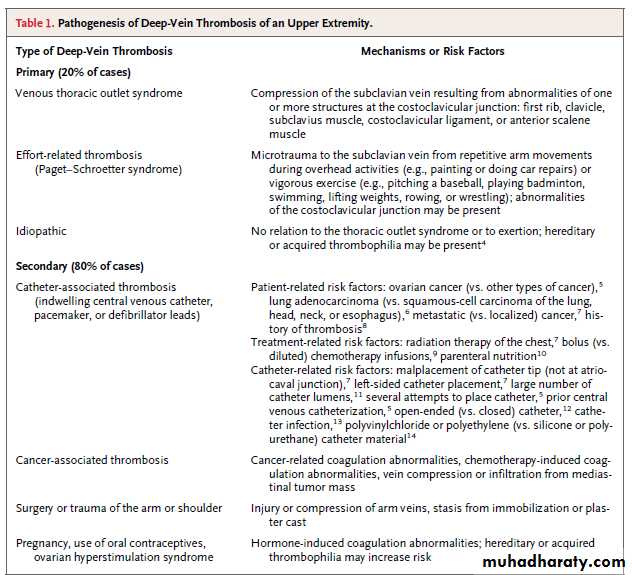

Approximately 10% of all cases of deep-vein thrombosis involve the upper extremities,have become more common because of the increased use of central venous catheters and of cardiac pacemakers and defibrillators. Axillary subclavian veins are often involved, and secondary forms are more common than primary forms .As compared with patients who have thrombosis of a lower extremity, patients with deep-vein thrombosis of an upper extremity are typically younger, leaner, more likely to have a diagnosis of cancer, and less likely to have acquired or hereditary thrombophilia.

Repetitive microtrauma to the subclavian vein and its surrounding structures, the result of anatomical abnormalities within the costoclavicular junction, may cause inflammation,venous intima hyperplasia, and fibrosis, all of which characterize the venous thoracic outlet syndrome. Approximately two thirds of patients with primary deep-vein thrombosis of an upper extremity, most of whom are young and male, report strenuous activity involving force or abduction of the dominant arm before the development of thrombosis, known as the Paget–Schroetter syndrome

Complications of deep-vein thrombosis, which are less common in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities, include

• Pulmonary embolism (6% for upper extremities, vs. 15 to 32% for lower extremities),

• Recurrence at 12 months (2 to 5% for upper extremitiesvs. 10% for lower extremities), and

• The post-thrombotic syndrome (5% for upper extremities vs. up to 56% for lower extremities).

The management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

The UK screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) will screen all men aged 65 to facilitate surveillance for small aneurysms or operative repair for large onesUltrasound surveillance for small aneurysms (<5.5 cm) is safe and cost effective.All patients with AAAs have a high cardiovascular risk and warrant aggressive risk factor management, including smoking cessation.The risk of aneurysm rupture outweighs that of postoperative morbidity and mortality for aneurysms >5.5 cm in patients with reasonable comorbidity.Definitive management requires operative repair; endovascular (in morphologically suitable aneurysms) repair is associated with lower early and midterm mortality than open repair.Surgical repair should be performed in high volume centres by experienced practitioners providing endovascular and open repair

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a permanent dilation of the abdominal aorta greater than 3 cm in diameter . The natural course is one of progressive enlargement, and maximum aortic diameter is the strongest predictor of aneurysm rupture. The reported incidence of AAA is 4.9-9.9%, and mortality after rupture exceeds 80%, accounting for 8000 deaths annually in the United Kingdom. Elective surgical repair has an operative mortality of 1-5% in the best centres, and several countries have implemented population screening programmes to reduce aneurysm related mortality.

original article

Apixaban with Antiplatelet Therapyafter Acute Coronary Syndrome

Background

Apixaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, may reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic

events when added to antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome.

NEJM July 2011

Results

The trial was terminated prematurely after recruitment of 7392 patients because of an increase in major bleeding events with apixaban in the absence of a counterbalancing reduction in recurrent ischemic events.Conclusions

The addition of apixaban, at a dose of 5 mg twice daily, to antiplatelet therapy in highrisk patients after an acute coronary syndrome increased the number of major bleeding events(A greater number of intracranial and fatal bleeding events occurred with apixaban than with placebo). without a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events.

Angiotensin-Receptor Blockers Aren't Associated with Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes

In contrast to results from a 2004 study, a meta-analysis showed no excess risk.Journal Watch General Medicine May 19, 2011

• In 2004, a randomized trial suggested that valsartan (Diovan), an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB), was associated with excess risk for myocardial infarction (MI; JW Gen Med Jul 13 2004). In this systematic review and meta-analysis, investigators assessed whether risks for adverse cardiovascular (CV) and other outcomes were associated with use of ARBs.

The analysis included 37 randomized trials in which placebo or active antihypertensive treatments were compared with ARBs (147,000 patients with average follow-up of 3.3 years). Compared with placebo or active-treatment, ARBs were not associated with excess risk for all-cause death, CV-related death, or angina (relative risks, 1.0 for all outcomes). Furthermore, ARBs were not associated with excess risk for MI (RR, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.92–1.07). In contrast, ARBs were associated with significantly lower risks for stroke (relative reduction, 10%), heart failure (13%), and new-onset diabetes (15%). The results were similar when ARBs were compared with either placebo alone or with active treatment alone.

FDA Announces Safety Review of Olmesartan

The FDA is reviewing the safety of the angiotensin-receptor blocker olmesartan (Benicar) after two ongoing trials among patients with type 2 diabetes suggested increased risk for cardiovascular death with the drug. For now, the agency emphasizes that it has not concluded that olmesartan increases the risk for death, and that the drug's benefits continue to outweigh its risks.Physician's First Watch June 14, 2010

In one trial that prompted the safety review, the incidence of cardiovascular death was 0.67% with olmesartan and 0.14% with placebo. In the other trial, the incidence was 3.5% and 1.1%, respectively.

The FDA notes that other controlled trials evaluating olmesartan have not indicated heightened risk for cardiovascular death. The agency advises clinicians to continue prescribing the drug according to its label, and to report any adverse events to the MedWatch program.

No Cancer Risk Elevation From ARBs: Two New Analyses

The new meta-analysis combined 15 trials, with follow-ups of up to 60 months, that randomized patients to ARB-containing therapy or a comparator group. Allocations included ARB vs ACE inhibitor in five trials, ARB vs treatment not containing ACE inhibitors in 11 trials, ARB plus ACE inhibitor vs ACE inhibitor alone in seven trials, and ARB plus ACE inhibitor vs ARB alone in two trials. have concluded that treatment with an angiotensin-receptor blocker does not increase the risk of cancer compared with non-ARB therapy.2011 Medscape

BMJ 2011;342

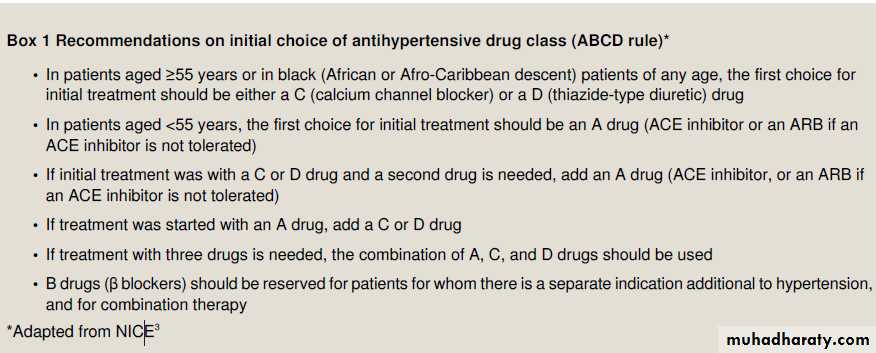

First line antihypertensive drugs are classified as

A, B, C, D. Drugs classed as A comprise (ACE) inhibitors and (ARBs); B drugs are β adrenoceptor antagonists and have fallen out of favour for use as single agents in patients in whom uncomplicated essential hypertension is the sole indication for drug treatment; C drugs are calcium antagonists;and D drugs are diuretics.BMJ 2011;342

Randomised controlled trial data show that untreated patients with essential hypertension with normal or raised plasma renin concentration (for example,many younger <55 years patients with essential hypertension, especially those who have successfully reduced their dietary salt intake) respond rather better to A and B drugs,

whereas those with low renin (such as people of African origin and older >55 years patients) respond well to C or D drugs). B drugs are no longer preferred as aroutine initial treatment for adults with hypertension.

BMJ 2011;342

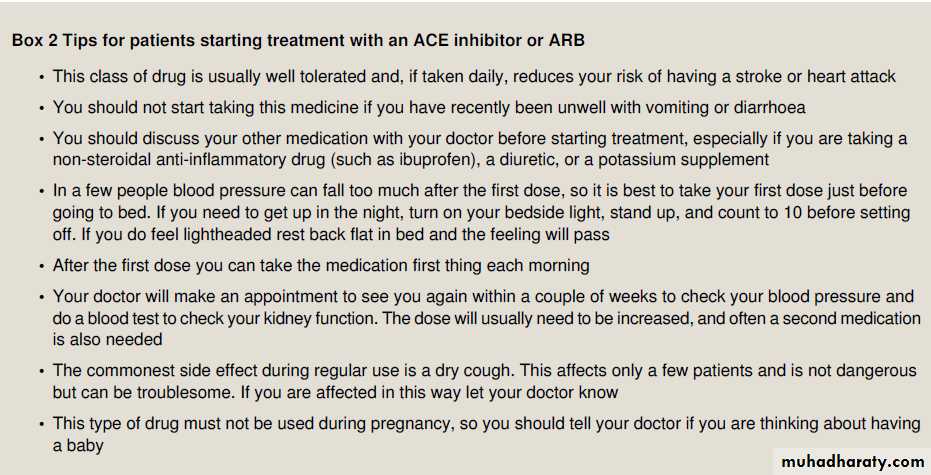

ACE inhibitors and C and D drugs, in doses that have similar effects on blood pressure, reduce cardiovascular risk in hypertension to a similar extent. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, detected with electrocardiography or with echocardiography ,is greater during treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs than with other drugs and is associated with fewer admissions to hospital for heart failure.Separate indications for ACE inhibitors include the treatment of heart failure and of ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction (for which they improve survival) and in slowing the decline in renal function in patients with diabetic and other forms of nephropathy .In general,ARBs seem to have effects similar to those of ACE inhibitors for these indications.

Responsiveness to ACE inhibitors and ARBs depends on renin activity, which is usually higher in younger patients and is strongly influenced by volume status; this underlies the importance of dietary salt restriction and explains why addition of a diuretic to an A drug is highly effective.

First dose hypotension

This adverse effect is probably more common with short acting ACE inhibitors (for example, captopril), which have a higher ratio of peak to trough plasma concentration after each dose than do longer acting ACE inhibitors (for example, ramipril andlisinopril). This is seldom problematic for patients with hypertension (whereas it might be for those with other indications—for example, heart failure and after myocardial infarction) unless their blood volume is reduced (for example,by potent diuretics, salt restriction, or vomiting and diarrhoea).

How safe are ACE inhibitors and ARBs?

ACE inhibitors have the following adverse effects.

BMJ 2011;342

Dry cough

Dry cough is the most common symptom in long term use ofan ACE inhibitor (4-30% of patients); its incidence is similar for all ACE inhibitors. In the ONTARGET study,16 only 4.2% of patients in the ACE inhibitor arm stopped their treatment.

(ramipril) because of intractable cough compared with 1.1% in the arm taking an ARB (telmisartan); Dry cough is twice as common in women, and in some patients

this may take several weeks to resolve after treatment is stopped.The cause is unknown but may be related to sensitisation of cough afferent nerve fibres caused by accumulation of kinins.

Renal failure

Acute renal impairment occurs predictably in response to ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients with haemodynamically significant bilateral renal artery stenoses or with renal artery stenosis in the vessel supplying a single functional kidney.Monitor serum creatinine and potassium concentrations by obtaining a baseline measurement before starting treatment then a repeat measurement one to two weeks later, and consider the possibility of renal artery stenosis in patients with a pronounced rise in creatinine concentration. Provided that the drug is stopped promptly, such renal impairment is reversible. Glomerular filtration in such patients critically depends on selective angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction of efferent (rather than afferent) arterioles, and when angiotensin II synthesis is inhibited or angiotensin II action is blocked, glomerular capillary pressure falls and glomerular filtration declines.Glomerular filtration in such patients critically depends on selective

angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction of efferent (rather than afferent) arterioles, and when angiotensin II synthesis is inhibited or angiotensin II action is blocked, glomerular capillary pressure falls and glomerular filtration declines.Renal failure may also occur among patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs if they have salt and volume depletion or concurrently take loop diuretics and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In the absence of renal artery stenosis,

volume depletion, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,ACE inhibitors or ARBs protect renal function and are not contraindicated simply because of a rise in baseline serum creatinine concentration.

When ACE inhibitors or ARBs are used in patients with severe chronic renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) there are two potential problems:

(a) if the drug or its active metabolite is entirely (for example, as with lisinopril) or partly (for example, as with losartan) renally eliminated, usual doses will result in drug accumulation and increased plasma and tissue concentrations; and

(b) Susceptibility to adverse effects such as hyperkalaemia is increased. The British National Formulary recommends lower initial doses and careful monitoring of creatinine and electrolytes in such patients, and prescribers should check the mode of elimination of individual agents .

Hyperkalaemia

Hyperkalaemia is potentially hazardous, especially in patients with renal impairment. Diabetes, especially with nephropathy,is a risk factor for hyperkalaemia. Patients taking potassium supplements, potassium sparing diuretics, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are particularly at risk. Monitor serum potassium accordingly: baseline creatinine and electrolytes should be obtained and repeated after one to two weeksUrticaria and angio-oedema

possibly caused by accumulation of kinins) are uncommon but potentially severe. Angio-oedema is five times more common in patients of African ancestry. If angio-oedema occurs the ACE inhibitor should be substituted with a different drug that is not an ACE inhibitor; if the blood

pressure response to the ACE inhibitor was good then an ARB is a suitable choice, but if not, then a drug of a different class( C or D) is appropriate. Rechallenge with any ACE inhibitor should not be undertaken as recurrent angio-oedema may occur after an unpredictable interval and can be life threatening.

Fetal injury

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are contraindicated in pregnancy. In the early stages of pregnancy, both these drug groups are associated with fetal skull defects. Later in pregnancy, they predictably cause renal impairment in the fetus, sometimesmanifested as oligohydramnios. Drugs of another class are therefore usually preferred in women who may want to have children.

What are the precautions when starting

an ACE inhibitor or ARB?Before starting treatment, review the history, especially the drug history, and note any findings that might suggest hypovolaemia,renal dysfunction, or electrolyte imbalance .Renin and aldosterone are not measured routinely because of cost, but any available measurements should be reviewed as they may point

to secondary hypertension and may influence treatment choice.

For example, raised aldosterone concentration with suppressed renin concentration suggests primary hyperaldosteronism and that the patient is unlikely to respond to ACE inhibitors;

raised aldosterone concentration with high renin concentration indicates the possibility of renal artery stenosis. Discuss the proposed plan with the patient (supported if they wish by a friend or relative), including alternative treatments and the possibility of known adverse effects. Start treatment using a small dose with advice to reduce risks of first dose hypotension .If the patient is also taking a diuretic, ask them to stop it for one to two days before the first dose for the same reason

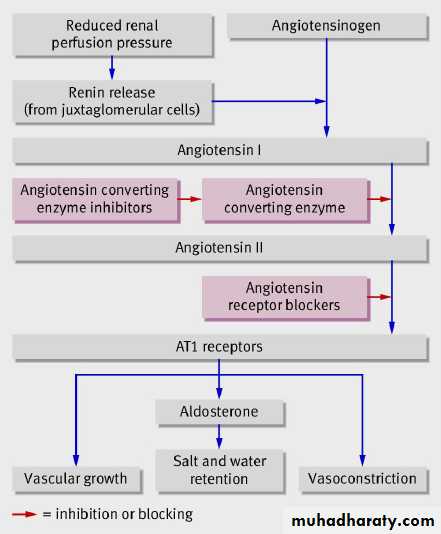

The renin-angiotensin pathway. Renin is released from juxtaglomerular cells in the kidney and catalyses the formation of

(inactive) angiotensin I from its substrate angiotensinogen. Angiotensin converting enzyme catalyses the conversion of

angiotensin I to the biologically active octapeptide angiotensin II. Angiotensin II acts on AT1 receptors on vascular smooth

muscle cells (causing vasoconstriction and stimulating cell growth) and on the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal glands

(stimulating release of aldosterone, which causes salt and water retention through sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron)

Mean arterial pressure (MAP]

Equation: MAP = [(2 x diastolic)+systolic] / 3Diastole counts twice as much as systole because 2/3 of the cardiac cycle is spent in diastole.

An MAP of about 60 is necessary to perfuse coronary arteries, brain, kidneys.Usual range: 70-110

• where PP is the pulse pressure, SP − DP

Blood pressure and body fat monitoring wristwatch

The Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitor

The Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitor

Ticagrelor: The View From the FDAThe US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has just approved ticagrelor, a new oral antiplatelet agent, for prevention of thrombotic events in patients with acute coronary syndromes. It is contraindicated in those with a history of intracranial hemorrhage, active pathological bleeding or severe hepatic impairment.

Medscape 07/29/2011

Missing a dose will not result in a platelet activation level that is any lower than if you took clopidogrel without missing a dose. In some ways, this is a disappointing finding. The potential that this agent would be rapidly reversible, and therefore useful for patients requiring an invasive procedure like a coronary artery bypass graft, was not realized. As recommended in the label, clinicians should ideally discontinue ticagrelor 5 days before surgery.

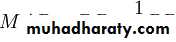

Acute aortic dissection

Acute aortic dissection is caused by an aortic intimal tear with propagation of a false channel in the media. Depending on the site and extent of the tear, it may cause chest, back, or abdominalpain, or collapse caused by rupture or malperfusion (transient or persistent ischaemia of any organ as a result of arterial branch obstruction).

BMJ 2011;343:

Although most patients present within two hours of onset of symptoms (usually to non-cardiac surgical centres), definitive diagnosis may be delayed by over 12 hours. Patients with dissection are commonly hypertensive men in their 60s, but all ages are affected (27% are aged 17-59 years,40% aged 60-74 years, 33% aged >75 years), including young adults, some with connective tissue disorders, such as

undiagnosed Marfan syndrome. In older patients, other conditions are more prevalent, and in the young, the diagnosis may not be considered.

Why is aortic dissection missed?

The clinical features at presentation (table ) may be sensitive but highly non-specific indicators and in some instances may include features of ischaemia from malperfusion (such as neurological deficits), which may confuse the clinical diagnosis. Electrocardiographic and troponin abnormalities resulting from coronary malperfusion are common and diagnostically misleading. Although changes in chest radiographs are common (89%), a normal chest radiograph doesnot exclude the diagnosis, and anterioposterior projections are

unreliable.

For type A acute aortic dissection, untreated mortality is 1-2% per hour in the first day, with a 90% mortality at 30 days. With surgery, this can be converted to 75-90% survival, and no more than two patients need treatment to gain survival advantage.Rapid recognition and treatment (within hours) may prevent the survival attrition and maximise recovery of reversible malperfusion phenomena (including neurological deficit).

Misdiagnosis as acute coronary syndrome may lead to inappropriate administration of anti-platelets and thrombolysis,complicating surgery. For all cases of acute aortic dissection, delayed diagnosis may delay antihypertensive treatment,allowing propagation and worsening of prognosis.

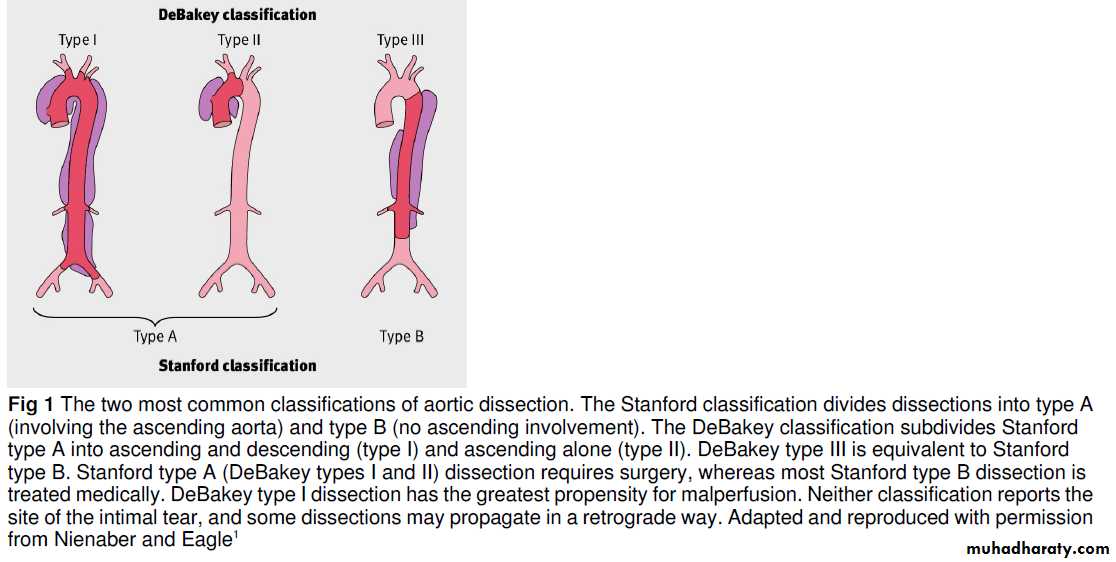

How is acute aortic dissection diagnosed?

ClinicalA triad of symptoms—characteristic chest pain (usually abrupt and/or severe), a pulse deficit or blood pressure differential, and an abnormal chest radiograph—increases the likelihood of dissection but is present in only a third of patients. A pulse deficit is the unilateral absence or diminution of a pulse compared with contralateral palpation. To detect this, a full peripheral pulse examination is mandatory (radial, brachial,carotid, and femoral pulses). The blood pressure differential is defined as a difference in systolic blood pressure between both arms of >20 mm Hg.

How common is acute aortic dissection?

• The estimated annual incidence is 30-43 per million of the population and may be increasing

• However, it is relatively uncommon, accounting for 1 in 300-350 emergency admissions for chest pain4

• For every emergency admission for dissection, there are 100 patients with acute myocardial infarction and 25 with pulmonary embolism

Patients with a suspected clinical diagnosis of acute aortic dissection should have basic investigations. These include electrocardiography, chest radiography, and blood tests for markers of myocardial ischaemia. Normality or abnormality of any of these does not exclude dissection; however, if further

imaging rules out dissection, then they may be of use in future patient management.

Once clinically suspected, a definitive diagnosis is made with cross sectional imaging (computed tomography of the aorta or magnetic resonance angiography) or transoesophageal echocardiography;

each of these imaging techniques has high diagnostic accuracy.

If computed tomography is done, images of the thoracic aorta should be obtained before injection of contrast to allow the detection of intramural haematoma (a condition that may progress to

dissection). In the absence of trauma, computed tomography is not routine. Transthoracic echocardiography may be specific but is insensitive and operator dependent and does not exclude

the diagnosis. Biomarkers may have a role: raised concentration of D-dimer is sensitive but non-specific, raising the suspicionfor both dissection and the differential diagnosis of pulmonary embolus.

How is acute aortic dissection managed?

Administer analgesia for pain relief and control hypertension with intravenous β blockade, and refer all patients to cardiac surgical centres:(a) in patients with type A dissection, for

emergency surgery to prevent intrapericardial rupture, restore true luminal flow and aortic valve competence, and to correct malperfusion;

(b) in patients with type B dissection, for medical

management and assessment for complications, which may require surgical or endovascular intervention.

BMJ 2011;343:

The Carey Coombs murmur is a short mid-diastolic murmur caused by active rheumatic carditis with mitral-valve inflammation. The murmur is soft and low pitched, heard best at the apex. The murmur is frequently transient,with onset during acute rheumatic mitral valvulitis and improvement or resolution with recovery from the acute illnessIt is thought that the murmur is the result of turbulence caused by thickened mitral-valve leaflets. Although similar to the diastolic rumble of mitral stenosis, the Carey Coombs murmur does not have an opening snap, presystolic accentuation,or a loud first sound, but may follow an S3 gallop. The latter may be superficially confused with an opening snap.

Coronary stents

first generation bare metal stents and later drug eluting stents.The main complication after stent insertion is restenosis of the stented artery, which may require revascularisation procedures.Restenosis is caused by proliferation of cells in the intima, a smooth muscle wall in the coronary vessel (neointimal hyperplasia), which together with clots can occlude the stented artery.

To help reduce restenosis, drug eluting stents that release anti-proliferative agents—such as sirolimus, tacrolimus, paclitaxel, and zotarolimus—were developed and introduced at the beginning of the 21st century.

Rates of revascularisation at one year for drug eluting stents within individual trials were less than 5% compared with 10-25% for bare metal stents.

According to UK national audit data, by 2008, 92% of percutaneous coronary intervention procedures involved stents, with more than 60% of these using drug eluting stents.

Guidelines vary by country, but in the UK, drug eluting stents are recommended for the treatment of coronary artery disease if the artery to be treated is less than 3 mm wide or the lesion is longer than 15 mm, and if the drug eluting stent is no more than £300 (€335; $480) more expensive than the bare metal stent.

In a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, the incidence of definite or probable

in-stent thrombosis one to four years after implantation was 0.9% in the sirolimus and paclitaxel eluting stent groups versus

0.4-0.6% in the bare metal stent group,

• More than 90% are caused by cancer.

• Non-malignant causes include• Intravascular devices,

• aortic aneurysms, and

• fibrosing mediastinitis.

Superior vena cava obstruction

Superior vena cava obstruction may be caused by extravascular compression, direct neoplastic invasion, or intravascular obstruction.

Extravascular compression of the superior vena cava is typically caused by cancer arising from the right upper lobe or main bronchus, or enlarged mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Neoplastic growth may also invade the superior vena cava and become afocal point for thrombus formation. Cancer accounts for more than 90% of cases of superior vena cava obstruction.

The most common cancers are non-small cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and metastatic deposits.

Thymomas and germ cell tumours are rarer causes. The prognosis for both types of lung cancer is poor, with a two year survival of about 5% for each. Other benign causes include aortic aneurysms and fibrosing mediastinitis In addition, infectious causes, such as klebsiella of the right upper lobe,nocardia, mycobacteria, and amoebiasis, have been reported.

Intravascular obstruction is becoming more common with the increasing use of intravascular devices, such as long term central venous catheters or pacemaker electrodes, which can cause thrombosis.

Obstruction of the superior vena cava used to be considered amedical emergency. This is now known not to be the case for most patients, because outcome is unrelated to symptom

duration. However, it becomes an emergency if patients develop dyspnoea and stridor (as a result of bronchial or laryngeal oedema) or

decreased consciousness (as a result of cerebral oedema), so vigilance is required.

The first step in managing superior vena cava obstruction is to raise the patient’s head to reduce oedema by reducing

hydrostatic pressure.

High dose dexamethasone, typically 4 mg

four times daily, is often used.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are used traditionally in patients with malignant obstruction, and treatment depends on the stage,grade, and type of cancer. It can take two to four weeks to take effect and is associated with high rates of complications and relapse. Systemic chemotherapy can lead to rapid relief of symptoms in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, small cell lung cancer,and germ cell tumours. Patients with a thymoma should have chemotherapy followed by surgical resection. It is important that stenting is avoided in these patients because it complicates resection.

Surgical treatment of superior vena cava obstruction involves bypass grafting using an autologous vein graft or a synthetic

tube. Good patency results can be achieved but postoperative morbidity is high. Such an invasive treatment, which requires a sternotomy, may not be appropriate in patients with a poor life expectancy, especially when stenting is a practical alternative.

Stenting is indicated if life threatening symptoms are present because it provides the most immediate relief of symptoms. It should also be considered in patients with advanced cancer when effective treatment options are limited (for example, those with mesothelioma or in the palliative stage of cancer). After placement of the expandable metal stent,symptomatic improvement is usually seen within 24-72 hours.

Because these stents are thrombogenic in the first four weeks,patients are sometimes given anticoagulants for this period after

the procedure, although the need and effectiveness of anticoagulation is unclear.

Other complications associated with stents are rare but include stent migration, acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, and cardiac tamponade. Migration of the stent to the heart can lead to death.

Thrombolytics may be needed to dissolve the thrombus before stent placement in patients with extensive intravascular thrombosis; otherwise, there is a risk of thrombus migration and pulmonary embolism. More recently, catheter directed thrombolysis has been used, followed immediately by thrombus aspiration to remove the remaining pieces of clot, before insertion of the stent. The administration of thrombolytics is associated with increased morbidity, however, mostly from haemorrhage. It has been suggested that a longer follow-up of

patients is needed to further evaluate the efficacy of this

intervention.

Management of stable angina: summary of NICE guidance

This is one of a series of BMJ summaries of new guidelines based on the best available evidence; they highlight important recommendations for clinical practice, especially where uncertainty or controversy exists.BMJ 5 August 2011;343

Stable angina is common. In England about 8% of men and 3% of women aged 55-64 years and about 14% of men and 8% of women aged 65-74 years have or have had angina.1 Stable angina is associated with a low but appreciable risk of acute coronary events and increased mortality. However, evidence exists of inconsistencies in management. This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) on the management of stable angina.

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available,recommendations are based on the Guideline Development Group’s experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice.Information and support for people with stable angina

Explain stable angina and its long term course andmanagement. Inform about factors that can provoke angina—for example, exertion, emotional stress, exposure to cold, or eating a heavy meal.

Explore and correct any misconceptions about stable angina

and its implications for daily activities, heart attack risk,and life expectancy. Individual patients may benefit from discussion about:-Self management skills such as pacing their activities and goal setting

-Concerns about the impact of stress, anxiety, or depression on angina

-Advice about physical exertion including sexual activity.

Assess the person’s need for lifestyle advice—for example,

about weight control, diet, stopping smoking, and exercise—and for psychological support. Offer interventions on an individual basis as necessary.Do not prescribe vitamin or fish oil supplements to treat stable angina. Advise people that there is no evidence that they help stable angina.

Preventing and treating episodes of angina

Give a short acting nitrate for preventing and treating episodes of angina. Advise people:-How to use the short acting nitrate

-To use it during episodes of angina and immediately before any planned exercise or exertion. -That side effects such as flushing, headache, and light headedness may occur

-To sit down or find something to hold on to if feeling light headed.

Tell people that when treating an episode of angina, they

should:

-Repeat the dose after five minutes if the pain has not gone

-Call an emergency ambulance if the pain has not gone five minutes after taking a second dose.

Advise the person with stable angina to seek professional

help if they have a sudden worsening in the frequency or severity of their angina.

Drug treatment

General principlesOptimal drug treatment for initial management consists of one or two anti-angina drugs as necessary to treat symptoms plus drugs for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Explain the purpose of the drug treatment, why it is

important to take the drugs regularly, and how side effects of drug treatment might affect the person’s daily activities.

Titrate the drug dosage against the person’s symptoms up to the maximum tolerable dosage.

Review the person’s response to treatment, including any side effects, two to four weeks after starting or changing drug treatment.

Offer either a β blocker or a calcium channel blocker as first line treatment.

Do not routinely use anti-angina drugs other than β blockers or calcium channel blockers as first line treatment.

If the person’s symptoms are not satisfactorily controlled

on a β blocker or a calcium channel blocker, consider

switching to the other option or using a combination of the two.

If the person cannot tolerate a β blocker, consider switching to calcium channel blocker (and vice versa).

For people taking either a β blocker alone or a calcium channel blocker alone whose symptoms are not controlled and the other option is contraindicated or not tolerated,consider one of the following as an additional drug:

• -A long acting nitrate or

• -Ivabradine, a selective inhibitor of pacemaker activity in the sinus node, or

• -Nicorandil, a vasodilator, or

• -Ranolazine, which acts on intracellular sodium currents to reduce myocardial ischaemia.

Do not offer a third anti-angina drug to people whose stable

angina is controlled with two anti-angina drugs. Add a third anti-angina drug only when:-The person’s symptoms are not controlled satisfactorily with two anti-angina drugs and

-The person is waiting for revascularisation, or

revascularisation is not considered appropriate or

acceptable.

When a choice of drug exists, decide which one to use on the basis of comorbidities, contraindications, the person’s preference, and drug costs.

Consider aspirin 75 mg daily for people with stable angina,

taking into account the risk of bleeding and comorbidities.Offer statin treatment and treat high blood pressure in line

with the NICE guidelines on lipid modification and

hypertension.

Consider angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors for people with stable angina and diabetes.

Continue these drugs in people who are taking them for other conditions.

Investigation and revascularisation

When symptoms are not controlled satisfactorily

on optimal medical treatment

Consider revascularisation and offer coronary angiography to guide treatment strategy. Additional non-invasive or invasive functional testing may be required to evaluate

angiographic findings and guide treatment decisions.

Examples of non-invasive functional

tests include dobutamine stress echocardiography and myocardial perfusion imaging

When either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery would be appropriate:

-Explain the risks and benefits of PCI and CABG surgery for people with anatomically less complex disease. If the person does not express a preference for the latter, offer PCI in preference to CABG surgery as health economic modelling suggests that PCI is the more cost effective strategy.

Take into account the potential survival advantage associated with CABG surgery compared with PCI

for people with

• multivessel disease who have• diabetes, are over 65 years, or

• have anatomically complex three vessel disease, with or without involvement of the left main stem.

Discuss with patients the following:

-Their prognosis without further investigation-The low likelihood of their having left main stem disease or proximal three vessel disease

-The availability of CABG surgery to improve the

prognosis in the small subgroup of people with left main stem or proximal three vessel disease

-The process and risks of investigation and the benefits and risks of CABG surgery, including the potential survival gain—for example, in people with left main stem disease,such surgery may extend survival by a mean of 19 months over 10 years.

After this discussion consider a functional test or

non-invasive anatomical test (computed tomography angiography) to identify people who might gain a survival benefit from surgery. Functional or anatomical test results may already be available from diagnostic assessment.

If functional testing indicates extensive ischaemia or non-invasive anatomical testing demonstrates the likelihood of left main stem or proximal three vessel disease, and if revascularisation is acceptable and appropriate, consider coronary angiography. If angiography indicates left main stem disease or proximal three vessel disease, consider CABG surgery.

General principles for revascularisation

Consider the relative risks and benefits of CABG and PCI for people with stable angina using a systematic approach to assess the severity and complexity of the person’s coronary disease, in addition to other relevant clinical factors and comorbidities.Treatment

strategy should be discussed for, but not be limited to:-People with left main stem or anatomically complex three vessel disease

-People in whom doubt exists about the best method of revascularisation because of the complexity of the coronary anatomy, the extent of stenting required, or other relevant

clinical factors and comorbidities.

Ensure that people with stable angina receive balanced

information and have the opportunity to discuss thebenefits, limitations, and risks of continuing drug treatment,CABG surgery, and PCI to help them make an informed

decision about their treatment.

When either of these revascularisation interventions is appropriate, explain to the person that:

-The main purpose of revascularisation is to improve the symptoms of stable angina

-CABG surgery and PCI are effective in relieving

symptoms but repeat revascularisation may be necessary after either procedure, and the rate is lower after CABG surgery

-Stroke is an uncommon complication of each of these two procedures (incidence is similar)

-There is a potential survival advantage with CABG surgery for some people with multivessel disease.

Inform the person about the practical aspects of CABG and PCI. Include information about:

-Vein and/or artery harvesting

-Likely length of hospital stay

-Recovery time

-Drug treatment after the procedure, such as use of antiplatelet drugs.

Stable angina that has not responded to treatment

For people whose stable angina has not responded to drugtreatment and/or revascularisation, offer comprehensive

re-evaluation and advice, which may include:

-Exploring the person’s understanding of their condition

-Exploring the impact of symptoms on the person’s quality

of life

-Reviewing the diagnosis and considering non-ischaemic

causes of pain

-Reviewing drug treatment and considering future drug

treatment and revascularisation options

-Acknowledging the limitations of future treatment

-Explaining how the person can manage the pain

themselves

Specific attention to the role of psychological factors in pain

-Development of skills to modify cognitions and behaviours associated with pain.

Do not use transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, enhanced external counterpulsation, or acupuncture to manage stable angina as there is no evidence that these reduce frequency of angina.

Overcoming barriers

Implementing this guideline will require physicians to modify attitudes in favour of optimal medical management as the initial,sometimes the only, treatment strategy for patients with angina.Cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other healthcare professionals need to determine in multidisciplinary team discussions the most appropriate revascularisation strategies for patients.What’s new

Requirement for optimal medical treatment before consideration of revascularisationRecognition that patients who respond to optimal medical treatment with relief of angina may need no further treatment.

Recognition that, in patients for whom both percutaneous and surgical revascularisation is feasible, percutaneous revascularisation is a more cost effective approach .

Patients with stable angina are generally thought to have a good prognosis, although published information is limited.

In a large randomised trial, annual all cause mortality was 1.5%.12 Studies in primary care have reported higher annual mortality rates, ranging from 2.8% to 6.6%.The composite risk of a complication during coronary angiography is 1-2%, with a composite risk of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke of 0.1-0.2%.

The prevalence of left main stem disease in patients with stable angina whose symptoms are controlled by medical treatment is unknown.

The Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry reported in 1989 that of 20137 patients who had coronary angiography, left main coronary disease (≥50% stenosis) was found in 1477 patients (7.3%), but only 53 (3.6%) of these patients were asymptomatic. In a 2006 registry report of 13 228 patients having coronary angiography,

left main stem disease (≥60% stenosis) was found in 3.6%.17

In 2008 a report based on a national adult cardiac surgical database stated that isolated, first time elective CABG surgery was associated with an in-hospital mortality of 1%, and rates of repeat surgery for bleeding, new renal support

(haemofiltration or dialysis), and postoperative stroke were 2.9%, 1.8%, and 0.9% respectively. Operative mortality

increased with age (2.5% in those aged >75 years) and was higher in women and in patients with left main stem disease.

Future research

The guideline group identified the following areas as needing further research.

What is the long term value of adding newer anti-angina drugs to a calcium channel blocker?

Does routine angiography with a view to revascularisation improve outcomes in people with stable angina who are

receiving optimal medical treatment and have evidence of ischaemia?

Do early investigation and revascularisation improve longer term survival in what is considered “high risk” anatomy,

such as left main stem disease, in people whose symptoms are controlled with medical treatment?

What is the long term value of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with stable angina?

What is the value of self management plans for patients with stable angina?

In patients with atrial fibrillation and at least one additional risk factor for stroke, the use of apixaban, as compared with warfarin, significantly reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism by 21%, major bleeding by 31%, and death by 11%.

For every 1000 patients treated for 1.8 years,

apixaban, as compared with warfarin, prevented astroke in 6 patients, major bleeding in 15 patients,and death in 8 patients.

NEJM August 28, 2011

The predominant effect on stroke prevention was on hemorrhagic stroke,

with prevention of a hemorrhagic stroke in 4 patients per 1000 and prevention of an ischemic or unknown type of stroke in 2 patients per 1000.The alternative treatment regimen with apixaban (at a dose of 5 mg twice daily), which does not require anticoagulation monitoring, not only is more effective than warfarin for stroke prevention but also accomplishes this goal at a substantially lower risk of bleeding and with lower rates of discontinuation.

These findings are supported by the results

of the Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid[ASA] to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin

K Antagonist Treatment trial (AVERROES;

ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00496769),6 in

which the same apixaban regimen, as compared

with low-dose aspirin, was shown to substantially

reduce the risk of stroke without any difference

in the rates of major bleeding and with

lower rates of discontinuation.

Although major bleeding was less common with apixaban, at adose of 5 mg twice daily, than with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation, the use of the same dose of apixaban, as compared with placebo,

resulted in more bleeding in patients with

acute coronary syndromes who were receiving both aspirin and clopidogrel.

The significant reduction in mortality observed in our study was consistent with trends toward lower rates of death among patients receiving apixaban than among

those receiving aspirin in the AVERROES trial.

Two alternative oral anticoagulants, the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban, have recently been shown in randomized clinical trials to be at least as effective as warfarin in preventing stroke. Each of these agents, like apixaban, has the major advantage of convenience, since there is no need for anticoagulation monitoring.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy trial (RE-LY, NCT00262600) the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran administered in two doses per day was compared with openlabel warfarin. The 150-mg dose of dabigatran administered twice daily, as compared with warfarin, was shown to reduce the rate of stroke, including ischemic or unspecified stroke, with asimilar overall rate of bleeding, although the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding was increased.

The 110-mg dose administered twice daily was associated with a rate of stroke that was similar to that with warfarin but with a lower rate of major bleeding. Both doses resulted in lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage.

In our study, apixaban at a dose of 5 mg twice daily (with the recommendation to use a reduced dose in patients with a predicted higher drug exposure) appears to combine the advantages of each of the two doses of dabigatran, with both a greater overall reduction in the rate of stroke and alower rate of bleeding than the rates with warfarin.

As compared with warfarin, apixaban is also associated with a reduction in the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding and with consistently lower bleeding rates across age groups and all other major subgroups.

Fewer patients receiving apixaban had a myocardial infarction than those receiving either warfarin (in our study) or aspirin (in the AVERROES trial).

Rivaroxaban, the second new alternative, was

shown to be noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in theintention-to-treat analysis in the Rivaroxaban

Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF, NCT00403767). The rates of intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding were lower with rivaroxaban than with warfarin, but there was no advantage with respect to other

major bleeding.

The differences between our findings and those of other trials comparing novel anticoagulants with warfarin may be related to differences in the doses of drugs, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the drugs, patient populations, or

other features of the clinical-trial design.

The lower risk of hemorrhagic stroke associated with all three novel anticoagulants suggests that there is a specific risk associated with warfarin, possibly related to its inhibition of multiple coagulation factors or interaction between warfarin and tissue factor VIIa complexes in the brain.

In conclusion, in patients with atrial fibrillation,

apixaban was superior to warfarin in preventing

stroke or systemic embolism, caused less

bleeding, and resulted in lower mortality.

NEJM August 28, 2011

New Era for Anticoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation

For more than 50 years, warfarin has been theprimary medication used to reduce the risk of

thromboembolic events in patients with atrial

fibrillation. Despite its clinical efficacy, warfarin

has multiple, well-known limitations, including

numerous interactions with other drugs and the

need for regular blood monitoring and dose adjustments.Thus, clinicians and patients have been

eager to embrace alternative oral anticoagulants

that are equally efficacious but easier to administer.

NEJM August 28, 2011.

In this issue of the Journal, Granger and colleagues

report the impressive primary results of

the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other

Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation

trial (ARISTOTLE; ClinicalTrials.gov number,

NCT00412984).1 A total of 18,201 subjects with

atrial fibrillation and at least one additional risk

factor for stroke were enrolled in the trial and

were randomly assigned to receive the direct

factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (at a dose of 5 mg

twice daily) or warfarin (target international

normalized ratio [INR], 2.0 to 3.0).

The trial was designed to test whether apixaban was noninferior to warfarin with respect to efficacy. The investigators found that apixaban was not only noninferior to warfarin, but actually superior,reducing the risk of stroke or systemic embolism by 21% and the risk of major bleeding by 31%.

In predefined hierarchical testing, apixaban as compared with warfarin, also reduced the risk of death from any cause by 11%.

These results come on the heels of two other,

large, phase 3 trials in which novel anticoagulants were compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy trial (RE-LY, NCT00262600)2 and Rivaroxaban Once Daily OralDirect Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF, NCT00403767).3 The RE-LY trial evaluated the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in two different doses, 110 mg and 150 mg, both administered twice daily. ROCKET AF evaluated the direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban at a dose of 20 mg once daily.

The trials have a number of similar conclusions.

Apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban, as

compared with warfarin, all significantly reduce the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In fact, in all the studies, the reductions in the primary efficacy end point — which included hemorrhagic as well as ischemic stroke — were greatly influenced by this dramatic reduction in the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Of the three drugs, only dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg holds the distinction of also having significantly reduced the risk of ischemic stroke as compared with warfarin; nonetheless, even in this case, there was a greater influence on hemorrhagic stroke than on ischemic cerebrovascular events. Similarly, the risk of particularly serious bleeding was reduced with each of the three drugs, as compared with warfarin, and apixaban therapy also resulted in lower rates of all major bleeding.

Thus, the newer anticoagulants boast favorable bleeding profiles as compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation.

There is also a shared theme with respect to

mortality. Apixaban is the first of the newer anticoagulants to show a significant reduction in

the risk of death from any cause as compared

with warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80 to 0.99; P = 0.047). Although

the current findings are notable, both dabigatran

and rivaroxaban, as compared with warfarin,showed similar directional trends. In the RE-LY

trial, there was a borderline reduction in the risk

of death from any cause with dabigatran at a dose

of 150 mg, as compared with warfarin (hazard

ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.00; P = 0.051). Similar

trends in the risk of death from any cause

were observed with rivaroxaban in the intentionto-

treat analysis in ROCKET AF (hazard ratio, 0.92;

95% CI, 0.82 to 1.03; P = 0.15).

Thus, there is approximately a 10% reduction in the risk of death from any cause across these three trials in which the newer anticoagulants were compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Despite these similarities, there are important differences in the design of the studies and in the administration of the drugs. In the RE-LY trial, the assignments to dabigatran or warfarin were not concealed. In contrast, the ROCKET AF and ARISTOTLE trials successfully achieved a double blind design.

In the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials, dabigatran and apixaban were administered twice daily; in ROCKET AF, rivaroxaban was administered once daily. Subjects in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials could have only one additional risk factor for stroke, whereas ROCKET AF enrolled a higher-risk population. The mean percentage of time in which the INR was in the therapeutic range of 2.0 to 3.0 — a metric that assesses the quality of warfarin dosing — was 64% in the RE-LY trial, 55% in the ROCKET AF

trial, and 62% in the ARISTOTLE trial.

There were additional differences among the studies with respect to their statistical analysis plans and power. These factors highlight the challenges with cross-trial comparisons. Head-to-head studies, which are not currently available, would allow for direct assessments among these novel compounds.

Will these newer anticoagulants be better than

warfarin for the treatment of all patients withatrial fibrillation? The direct thrombin and factor

Xa inhibitors overcome the need for routine

blood monitoring, and the trial results have been

encouraging overall and across important subgroups.

For example, in the ARISTOTLE trial, the

efficacy of apixaban was consistent in subgroups

according to baseline stroke risk and according

to whether patients had or had not been taking

warfarin before entering the study. However

switching to a newer agent may not be necessary for the individual patient in whom the INR has been well controlled with warfarin for years.

In addition, although the newer anticoagulants have a more rapid onset and termination of anticoagulant action than does warfarin, agents to reverse the effect of the drugs are still under development and are not routinely available.

In addition, generic warfarin is expected to be

markedly less expensive than the newer agents

even after the costs associated with regular INR

monitoring are considered. One analysis has suggested that dabigatran, as compared with warfarin, could be cost-effective in patients with atrial fibrillation. Additional data on cost-effectiveness

are likely to further influence clinical decision

making.

Thus, although the oral direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors are attractive alternatives, it is likely that warfarin will continue to be used worldwide in many patients with atrial fibrillation.

The original mission to replace warfarin began with

a search for drugs that were simply noninferior to warfarin. The ARISTOTLE trial, in conjunction with the RE-LY and ROCKET AF trials, suggests that apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban have gone even further. Across three large studies with different populations of patients with atrial fibrillation, the direct thrombinand factor Xa inhibitors have been shown to

have a more favorable bleeding profile than warfarin

and are at least as efficacious.

Information about another direct factor Xa inhibitor, edoxaban, in patients with atrial fibrillation, will be available at the conclusion of the Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48, NCT00781391). After all this time, a new era of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation appears to be emerging for patients with atrial fibrillation.

NEJM August 28, 2011.