ASPIRIN

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2011

• Clay tablets from the Sumerian period describe the use of willow leaves to treat Rheumatism

Salicylic Acid

ON AUGUST 10th 1897, Felix offmann,a chemist in the employ of a German dyestuffs company called Bayer

managed to acetylate the phenol group of a compound called salicylic acid.

Bayer Advanced Aspirin employs breakthrough Pro-Release Technology that reduces the aspirin particles into micro-particles that are on average 10 percent of the particle size of previous Bayer Aspirin tablets. The technology combines a smaller particle size with a rapidly disintegrating tablet that results in Bayer Advanced Aspirin being quickly available in the stomach and readily absorbed. This combination helps Bayer Advanced Aspirin dissolve six times more quickly, enter the bloodstream four times as fast and rush relief right to the site of pain, providing pain relief twice as fast as before*.

• Aspirin is the most commonly used drug in the world.

• In the United States alone, one third of the adult population—some 50 million people—take an aspirin a day• to protect themselves from strokes and heart attacks and to help prevent a cardiovascular death.

Aspirin inhibits the clumping of platelets (in low doses)

pain kiling effects (medium dosese)

Antiinflammatory effects(high doses).

—

ACTIONS OF ASPIRIN

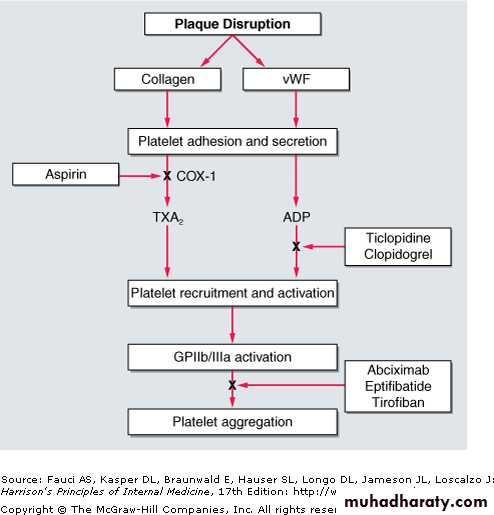

Aspirin inhibits thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis by irreversibly acetylating cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1). Reduced TXA2 release attenuates platelet activation and recruitment to the site of vascular injury.

What is the best dose for most people?

• systematic review concludes that patients taking aspirin long term• do best on doses of 75-81 mg a day.

• Higher doses don't work better but do increase the risk of side effects, especially gastrointestinal bleeding.

• Buffered or enteric coated aspirins seem no safer than traditional pills.

Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Patients with Diabetes

Recommendations from three professional organizationsThe American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the American Diabetes Association

Journal watch General Medicine July 8, 2010

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among patients with diabetes is substantial. Individuals with diabetes are at 2- to 4-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events compared with age- and sex-matched individuals without diabetes. In diabetic patients over the age of 65 years, 68% of deaths are from coronary heart disease (CHD) and 16% are from stroke.

A number of mechanisms for the increased cardiovascular risk with diabetes have been proposed, including increased tendency toward

intracoronary thrombus formation, increased platelet reactivity, and worsened endothelial dysfunction.

The three professional organizations have collaborated to produce a position statement on aspirin for primary prevention in patients with diabetes. The statement includes a meta-analysis of nine randomized trials, in which aspirin lowered risk for coronary events by 9% and for stroke by 15%; neither difference reached statistical significance.

The authors estimate that excess risk for gastrointestinal bleeding conferred by aspirin could be as high as 1 to 5 episodes per 1000 diabetic patients annually. Based on their balancing of benefits and harms, the authors make the following recommendations for primary prevention in adults with diabetes: (The risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) is 2 to 4 times greater for those with diabetes).

• Low-dose aspirin (75–162 mg daily) "is reasonable" for patients with 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk >10% and no risk factors for bleeding. This group would include most diabetic men older than 50 and women older than 60 who have at least one additional major risk factor (i.e., smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, family history of premature CVD, or albuminuria).

recommendations for primary prevention in adults with diabetes:

2. Aspirin "should not be recommended" for diabetic men younger than 50 and women younger than 60 with no other risk factors (10-year CVD risk, <5%).

3. Aspirin "might be considered" for those at intermediate risk (10-year CVD risk, 5%–10%); this group would include younger patients with, and older patients without, other risk factors.

Aspirin for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)March 2009

Summary of Recommendations

The USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for men age 45 to 79 years when the potential benefit due to a reduction in myocardial infarctions outweighs the potential harm due to an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage Grade: A recommendationThe current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of aspirin for cardiovascular disease prevention in men and women 80 years or older.Grade: I statement.

The USPSTF recommends against the use of aspirin for stroke prevention in women younger than 55 years and for myocardial infarction prevention in men younger than 45 Grade: D recommendation.

Assessment of Risk for Cardiovascular Disease Men

The net benefit depends on the initial risk for coronary heart disease events and gastrointestinal bleeding. Thus, decisions about aspirin should consider the overall risks for coronary heart disease and gastrointestinal bleeding.Risk assessment for coronary heart disease should include ascertainment of risk factors:

age, diabetes, total cholesterol levels, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, blood pressure, and smoking.Available tools provide estimations of coronary heart disease risk.

Women

The net benefit of aspirin depends on the initial risks for stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding. Thus, decisions about aspirin therapy should consider the overall risk for stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding.Risk factors for stroke include age, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, a history of cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Tools for estimation of stroke risk are available.

Assessment of Risk for Gastrointestinal Bleeding

The USPSTF considered age and sex to be the most important risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding. Other risk factors include ulcers, and NSAID use. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy combined with aspirin approximately quadruples the risk. The rate of serious bleeding in aspirin users is approximately 2 to 3 times greater in patients with a history of a gastrointestinal ulcer.Men have twice the risk for serious gastrointestinal bleeding than women. Enteric-coated or buffered preparations do not clearly reduce the adverse gastrointestinal effects of aspirin. Uncontrolled hypertension and concomitant use of anticoagulants also increase the risk for serious bleeding.

Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events With Aspirin:

A recent meta-analysis suggested that the absolute benefit of aspirin in primary prevention is, at best, extremely small (JW Gen Med Jun 18 2009); A low ankle-brachial index (ABI; ratio of systolic pressure at the ankle to that in the arm; normal range, 1.1–1.4) is a marker for peripheral vascular disease. Scottish investigators used ABI to screen asymptomatic patients who might benefit from aspirin for primary prevention of adverse cardiovascular (CV) events.Journal watch General Medicine March 11, 2010

A total of 3350 adults with ABI 0.95 (mean age, 62; 71% women; mean ABI, 0.86; 33% smokers) were randomized to receive aspirin (100 mg daily) or placebo. During a mean follow-up of >8 years, no between-group differences were observed for any adverse CV event, revascularization, or stroke (about 13.5 events occurred per 1000 person-years in each group), or for mortality. Risk for major hemorrhage was higher in the aspirin group than in the placebo group (2.0% vs. 1.2%) — a nearly significant difference.

However, given the increased level of risk among those with a low ABI, the use of alternative therapies, such as statins or more potent antiplatelet agents without attendant hemorrhagic risks may usefully be considered. In addition, given that the trial was a pragmatic trial in the context of ABI screening in the general population, aspirin might still have a net beneficial effect on patients with a low ABI, elevated risk factors, and a greater incentive to continue taking medication.

Don’t use aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

In primary prevention, the use of low dose aspirin is unlicensed in the United Kingdom, and published evidence does not support the assumption that the benefits clearly outweigh the harms. So the routine practice of starting patients on such treatment for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease should be abandoned.BMJ April 2010

Several guidelines published between 2005 and 2008 recommended aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in various groups of patients, including certain patients with type 2 diabetes, those with a cardiovascular disease risk of 20% or more over 10 years, and those with a 10 year risk of cardiovascular disease mortality over 10%. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network’s recently published guideline on management of diabetes states that low dose aspirin is not recommended for primary prevention of vascular disease in patients with diabetes.

However, the British Hypertension Society has recently reaffirmed its guidance promoting aspirin for primary prevention. These guidelines, coupled with the acceptance that low dose aspirin is useful for secondary prevention, may have led to widespread prescribing of aspirin for primary prevention. It is also worth noting that risk factors that predict vascular events also predict haemorrhagic events, so patients who will benefit from aspirin can be identified on the basis of risk scores only if they have already had a vascular event.

Does Proton-Pump Inhibitor Use Reduce the Antiplatelet Effects of Low-Dose Aspirin?

Apparently yes, but the effect on cardiovascular outcomes is not yet known.Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been shown to reduce the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel in patients who take this thienopyridine after an acute coronary syndrome event, but adverse effects on cardiovascular outcomes have not been demonstrated (JW Gastroenterol Oct 16 2009). Now, researchers from Denmark have conducted a case-control study of platelet function in 418 adults with stable coronary artery disease who were taking 75 mg/day of aspirin; 54 were also on a PPI (the majority on pantoprazole).

Compared with PPI nonusers, those taking a PPI had significantly higher platelet aggregation ,higher serum levels of soluble P-selectin, a cell-adhesion molecule stored in the alpha granules of platelets ,and higher serum levels of thromboxane B2 .

Journal watch Gastroenterology April 30, 2010

Is It Okay for Patients with Peptic Ulcer Bleeding to Continue Low-Dose Aspirin?

• For patients at cardiovascular risk, the short-term survival advantage of continuing aspirin therapy outweighed the bleeding risk.• Patients on aspirin therapy who present with peptic ulcer bleeding typically discontinue the aspirin to reduce risk for recurrent bleeding. However, does that risk actually outweigh the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin?

Journal watch Cardiology December 23, 2009

To address this question, researchers in Hong Kong recruited consecutive patients who presented with overt signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and who were taking low-dose aspirin ( 325 mg/day) for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular indications other than primary prophylaxis.

After undergoing successful endoscopic therapy and receiving high-dose intravenous proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, 156 patients (mean age, 74) were randomized to receive either placebo or 80 mg/day of aspirin for 8 weeks. Both groups received daily oral PPI therapy during follow-up

Twelve recurrent bleeding episodes were ultimately confirmed: eight in the aspirin group and four in the placebo group. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the 30-day cumulative incidence of recurrent ulcer bleeding was 10.3% in the aspirin group and 5.4% in the placebo group — a statistically nonsignificant difference. Within 30 days after randomization, 1 aspirin recipient and 10 placebo recipients died. Of the 10 deaths in the placebo group, 5 were from vascular complications. The estimated all-cause mortality rate at 8 weeks was significantly lower in the aspirin group than in the placebo group (1.3% vs. 12.9%).

In this small, short-term trial involving patients with bleeding peptic ulcers, patients who continued low-dose aspirin therapy had a higher rate of recurrent bleeding than those who stopped taking aspirin. However, that bleeding difference was nonsignificant, and — much more important — the mortality rate was significantly lower among the patients who continued the aspirin.

Although larger trials are needed to confirm these findings, we can reasonably consider allowing patients with peptic ulcer bleeding who are at high risk for cardiovascular events to continue receiving indicated aspirin therapy.

Pregnancy complicationsAspirin may reduce the risk of pregnancy complications in women with pre-eclampsia and in those with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS, Hughes syndrome).APS is an uncommon autoimmune disorder associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, low birth weight and foetal death. The use of aspirin may reduce the risk of these complications.

Pre-eclampsia is associated with poor intrauterine growth, premature birth and maternal death. Evidence that aspirin may reduce these complications suggests aspirin has a modest benefit in reducing risk without a significant risk of haemorrhage; there is currently no way of identifying which women will benefit from treatment.

Does long term aspirin prevent cancer?

The cardioprotective effects of aspirin are well established. A meta-analysis of individual subject data from primary prevention randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggested that aspirin can reduce the relative risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction by about 20%. Overall, however, the risks of treatment (severe gastrointestinal and extracranial bleeding) were roughly the same as the benefits, so routine use of aspirin as a primary preventive strategy was not recommended.• BMJ 2010; 341

The meta-analysis did not evaluate any potential reduction of mortality from cancer, as has been suggested by observational data. Observational data are difficult to interpret, however, because associations may not be causal and may be the result of confounding or bias.

Rothwell and colleagues have therefore conducted another meta-analysis of individual subject data from RCTs of aspirin versus no aspirin for prevention of vascular disease, but this time they evaluated mortality from cancer as the main outcome. They found a 21% (95% confidence interval 8% to 32%) reduction in the odds of death from cancer in people who took aspirin for almost six years, and the effect was strongest for gastrointestinal cancers. The authors suggest that this may now tip the balance in favour of using aspirin as a primary prevention strategy, both for ischaemic heart disease and cancer.

• BMJ 2010; 341

Aspirin taken for several years at doses of at least 75 mg daily reduced long-term incidence and mortality due to colorectal cancer. Benefit was greatest for cancers of the proximal colon, which are not otherwise prevented effectively by screening with sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

The Lancet 22 October 2010

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Chronic renal disease appears to reduce platelet responsiveness to clopidogrel, according to a Korean research team. Furthermore, increasing the dose of clopidogrel does not improve platelet responsiveness in these patients.

In their report in the November 1st issue of the American Journal of Cardiology, Dr. Weon Kim, at Kyung Hee University Medical Center in Seoul, and associates suggest that “the mechanisms for platelet dysfunction in patients with chronic renal failure include an increase in the platelet turnover rate, poor bioavailabilities such as disturbances of absorption or drug transportation, and coagulation disorders.”

The researchers compared platelet responsiveness to clopidogrel after coronary angiography or coronary or peripheral vascular intervention in patients with and without chronic renal failure. All patients except two in the renal failure group were men. Their average age was roughly 60 years. The 23 patients with normal renal function were given 75 mg of clopidogrel per day. The 36 with chronic renal failure were randomized to receive either 75 mg or 100 mg of clopidogrel per day.

After 4 weeks, blood was drawn to measure platelet aggregation by analyzing the degree of light penetration. The mean platelet inhibition was 35.2% among those with normal renal function, 21.3% among the renal failure patients on 75 mg of clopidogrel, and 23.4% among those on 150 mg (p = 0.026). The corresponding mean values of platelet aggregation in P2Y12 assay reaction units were 239.9, 308.7, and 302.7 (p = 0.013).

There was no significant difference in either measure between the two renal failure groups. The authors note that decreased renal function is a risk factor for thrombosis of drug-eluting stents. “Clopidogrel resistance might be an important mechanism for the high occurrence of stent thrombosis in patients with chronic renal failure,” they point out. “

Drug-eluting stents should be (used cautiously) in patients with chronic renal failure,” Dr. Kim and associates conclude. The investigators caution that their study was small, that variables other than platelet responsiveness were not investigated, and that their results cannot be generalized to women. Reference: Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1292-1295.

Although clopidogrel was overall highly effective at reducing adverse cardiovascular events in CREDO trial, this effect seemed to be greatest in patients with normal renal function, whereas patients with mild and in particular moderate CKD appeared to have experienced less of a benefit. Major bleeding was not increased from clopidogrel to a greater degree in CKD patients than in others. This finding represents an outlier compared with other aspirin-clopidogrel trials, such that confirmation of the effect of CKD is thus far lacking. More studies are needed to determine the optimal use of clopidogrel therapy in patients with CKD.

American Heart Journal. 2008;155

November 23, 2010 — Aspirin use in Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients does not slow progression of the disease and may increase the risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), a new systematic review of 2 trials suggests.

"What we know is that there's no indication to prescribe aspirin in order to slow down cognitive decline, and there's a potential increased risk of hemorrhage, so if there's no clear cardiovascular indication,

I think doctors should refrain from prescribing aspirin to Alzheimer's disease patients," said one of the study's authors, Edo Richard, MD, PhD, from the Department of Neurology at Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

But although the study found an increased rate of ICH, the results fall short of providing a sound basis for an across-the-board recommendation against the use of aspirin in AD, said Dr. Richard.

2010 Medscape

Care for patients with diabetes should include treatment to decrease the A1c level to less than 7%, blood pressure values to less than 130/80 mg/dL, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations to less than 100 mg/dL. Aspirin therapy is advised for men older than 50 years and women older than 60 years with diabetes plus 1 other cardiovascular risk factor.

2009 MedscapeCME

Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Patients with Diabetes

Recommendations from three professional organizationsThe American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the American Diabetes Association have collaborated to produce a position statement on aspirin for primary prevention in patients with diabetes. The statement includes a meta-analysis of nine randomized trials, in which aspirin lowered risk for coronary events by 9% and for stroke by 15%; neither difference reached statistical significance.

The authors estimate that excess risk for gastrointestinal bleeding conferred by aspirin could be as high as 1 to 5 episodes per 1000 diabetic patients annually. Based on their balancing of benefits and harms, the authors make the following recommendations for primary prevention in adults with diabetes:

• Low-dose aspirin (75–162 mg daily) "is reasonable" for patients with 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk >10% and no risk factors for bleeding. This group would include most diabetic men older than 50 and women older than 60 who have at least one additional major risk factor (i.e., smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, family history of premature CVD, or albuminuria).

• Aspirin "should not be recommended" for diabetic men younger than 50 and women younger than 60 with no other risk factors (10-year CVD risk, <5%).

• Aspirin "might be considered" for those at intermediate risk (10-year CVD risk, 5%–10%); this group would include younger patients with, and older patients without, other risk factors.

Benefits of Aspirin Therapy Outweigh Bleeding Risks in Hypertensive Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease

une 1, 2009 (Milan, Italy) — In a hypertensive population with (CKD), the benefit of aspirin therapy in reducing major cardiovascular events outweighs the risk for bleeding and, in fact, might be even greater than the benefit obtained by people with normal kidney function, according to an analysis of participants in the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study, presented here at the World Congress of Nephrology, a Joint Meeting of the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association and the International Society of Nephrology.

Renal patients are at great risk for cardiovascular disease but they often do not receive antiplatelet therapy," said principal investigator Meg Jardine, MD, from The George Institute for International Health in Sydney, Australia.

"For the first time we are showing that patients with renal dysfunction derive benefit from aspirin treatment. Major bleeding events may be increased but they are outweighed by the substantial protective benefits," she said.

The study involved 18,597 participants, aged 50 to 80 years, with diastolic blood pressure of 100 to 115 mm Hg and a baseline glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or less, including 536 patients with values less than 45 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Subjects were randomized to daily acetylsalicylic acid (75 mg) or placebo.

In the overall HOT population, the use of aspirin reduced major cardiovascular events by 15% (PÂ = .03), reduced myocardial infarction by 36% (PÂ = .02), and increased the risk for major bleeding by 80% (PÂ < .001).

The risk for major cardiovascular events was reduced by 66% (95% confidence interval [CI], 33% - 83%) in those with a baseline GFR of less than 45Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2, by 15% (95% CI, 17% - 39%) in those with a baseline GFR of 45 to 59Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2, and by 9% (95% CI, 9% - 24%) in those with a baseline GFR of 60Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2 or higher (PÂ = .03), Dr. Jardine reported at a late-breaking clinical-trials session.

Mortality was reduced by 49% (95% CI, 6% - 73%) in those with a baseline GFR of less than 45Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2 and by 11% (95% CI, 31% - 40%) in those with a baseline GFR of 45 to 59Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2(PÂ = .04); there was no significant reduction in those with a baseline GFR of 60Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2 or higher.

"This means that for every 1000 persons with a GFR less than 45Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2, aspirin would prevent 76 major cardiovascular events, 40 myocardial infarctions, 40 strokes, 40 cardiovascular deaths, and 54 all-cause deaths," Dr. Jardine concluded, "and would cause 27 excess major bleeds and 11 minor bleeds."

Bleeding Increased but Not Statistically Significant

The risk for major bleeding events was increased with aspirin by:291% (95% CI, 92% - 927%) for those with a baseline GFR of less than 45Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2

171% (95% CI, 74% - 391%) for those with a baseline GFR of 45 to 59Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2

153% (95% CI, 111% - 210%) for those with a baseline GFR of 60Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2 or higher.

But the differences between these groups was not statistically significant (PÂ = .27), she noted, and the absolute numbers were small. "There were so few bleeding events [that] we could not find them statistically significant," she said.

There were no fatal major bleeds caused by aspirin therapy, and only 27 nonfatal major bleeds in the worst renal-function group, which saw the most benefit. Nonfatal major bleeds occurred in 4 patients with a GFR of 45 to 59Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2, and in 5 patients with a GFR of 60Â mL/min per 1.73Â m2 or higher.

"Annual changes in GFR were minor, therefore CKD progression was not affected by aspirin therapy in any GFR group," she added.

Our findings suggest that aspirin should be used more widely in hypertensive people with CKD, particularly those at a lower risk of bleeding events," Dr. Jardine concluded.

Charles Herzog, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Special Studies Center of the US Renal Data System and professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said that to properly study the benefit of aspirin in these patients, a trial of 5,000 to 10,000 patients would be required, which the HOT trial was. He pointed out that the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative recommendation is to use aspirin for cardiovascular protection in patients with renal disease.

"I do advocate and prescribe aspirin in these patients," he said, "and I believe that unless they have a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, they should be on this therapy."

World Congress of Nephrology 2009: A Joint Meeting of the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) and the International Society of Nephrology (ISN): Abstract 766. Presented May 25, 2009.

Aspirin in primary prevention

GPs left in a quandaryThe recent BHS statement leaves general practitioners (GPs) with a dilemma of what to do with patients who are currently taking low dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.1

Most will have hypertension or diabetes, or both. They will have started aspirin treatment when type 2 diabetes was considered to be a secondary preventable disease or the Framingham based risk charts calculated their 10 year coronary heart disease risk to be >15% (CVD risk >20%).

BMJ 2010;340

In my practice a third of these patients are taking proton pump inhibitors, which will prevent most upper gastrointestinal bleeding and positively affect the benefit to risk ratio. Should they be?

Also in my practice about a quarter of these patients smoke, and meta-analysis suggests that smoking negates the beneficial aspects of aspirin treatment. Should I therefore stop aspirin in this group?

Most of the beneficial effects of aspirin are by reducing non-fatal myocardial infarction.2 As up to half of ischaemic heart disease first presents as myocardial infarction, does primary prevention with aspirin start thrombolysis early in any such cardiovascular event? Is the size of the infarct smaller if the patient is taking aspirin?

The possible "other" health advantages of low dose aspirin treatment are not considered. Low dose aspirin may prevent the development of colorectal or certain oesophageal cancers by between 20-60%.3 Should GPs factor this into their calculations?

GPs need clearer answers to these questions to make evidence based decisions. They must remember also that the absolute risk reduction in using aspirin is small, with a number needed to treat of 166 patients for 10 years to prevent one significant cardiovascular event.

BMJ 2010;340

The current totality of evidence provides only modest support for a benefit of aspirin in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease, which is offset by its risk. For every 1,000 subjects treated with aspirin over a 5-year period, aspirin would prevent 2.9 major cardiovascular events (MCEs) (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death) and cause 2.8 major bleeds.

08/04/2011; American Heart Journal

Meta-analysis of >100,000 randomized patients (>700,000 person-year follow-up) comparing aspirin versus placebo or control demonstrated that aspirin decreased MCE by approximately 10% among patients without clinical CVD. Major bleeding, however, occurred more frequently with aspirin therapy. The decision to use aspirin for the prevention of a first MI or stroke remains a complex issue. Weighing the overall benefit and risk requires careful consideration by the physician and patient before initiating aspirin for preventive therapy in patients without clinical CVD.