1

Professor Nada Al Alwan

Diagnostic Cytopathology

Definition: Diagnostic or Clinical Cytology is the study of the normal and disease-

altered cells obtained from various sites of the body (i.e., through the detection of

abnormal morphologic characteristics of the examined dissociated human cells).

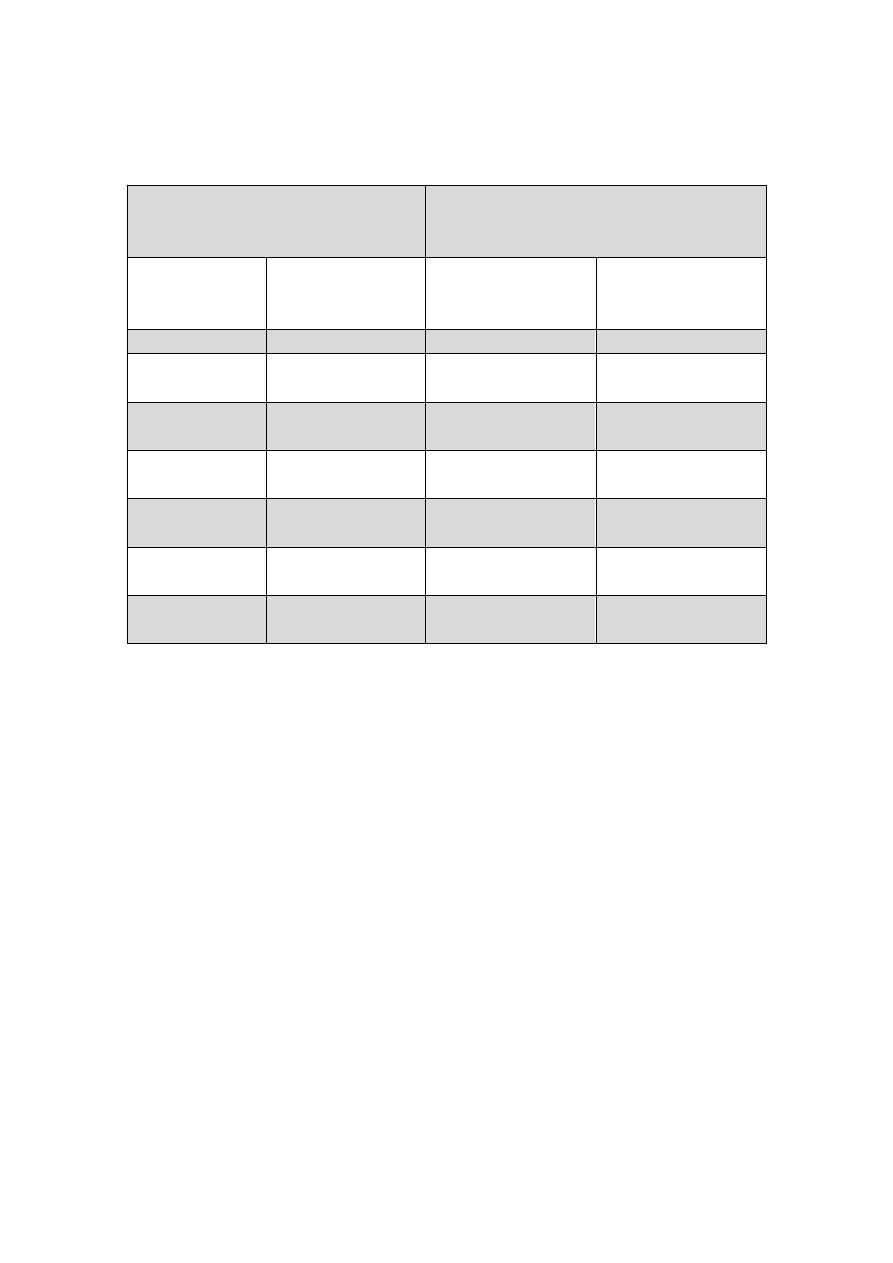

Cytopathology in Relation to Histopathology

Advantages of Cytopathology (c

ould be summarized in the following Table):

Limitations of Cytopathology:

As a rule, histopathology remains the gold standard technique in diagnostic pathology.

The whole presented tissue definitely provides a more accurate precise diagnosis of

the disease in question. The interpretation of the morphological cellular changes is

based mainly on individual observations and often cannot be forced into rigid criteria.

Histopathology

Cytopathology

Deals with the form and the

structure of the tissue.

Evaluation usually begins with a

tissue biopsy.

More invasive traumatic

procedure is needed; utilizing

surgical instrumentation such as

foreceps, scissors, etc..)

Needles if used should have a

large gauge (i.e., Tru-cut needles

measuring 14, 16 ) .

Diagnosis obtained after days.

Basic stain is H&E

Paraffin blocks are needed

Difficult to identify specific

causative inflammatory pathogen.

Deals with the structural changes

within the nucleus and cytoplasm

of individual cells

Evaluation requires cells only.

Inexpensive simple means of

diagnosis which allows frequent

repetition of cellular sampling

(since it causes no tissue injury).

Fine needles with 22, 23 or 24

gauge are usually preferred.

Rapid diagnosis that could be

obtained within minutes.

Basic stain is Pap stain (however

H&E could be used as well)

Mainly slides are needed

Smears permit better evaluation of

the nature of the inflammatory

process. Fungi and parasites are

usually easier to be diagnosed.

2

Thus, in many cases the cytological diagnosis could not be final and needs

confirmation by histopathology for the following reasons:

Often the nature of the lesion is not so obvious as in a histological section.

The location of the lesion is difficult to be pinpointed by cytology: for example a

squamous cancer cells found in a cytology sputum sample may have originated

from the buccal mucosa, pharynx, larynx or bronchi.

The size of the lesion cannot be approximated by cytology.

The type of the lesion –e.g., in situ carcinoma as compared with early invasion is

more difficult to assess since the relationship of the cells to the surrounding

stroma cannot be determined by cytology.

Sampling Techniques

In general, diagnostic cytology is based upon three basic sampling techniques :

(1) the collection of exfoliated cells,

(2) the collection of cells removed by brushing or similar abrasive techniques,

(3) the aspiration biopsy or removal of cells from nonsurface –bearing tissue (or

deep organs) by means of a needle, with or without a syringe.

1- Exfoliative Cytology

Exfoliative cytology is based on spontaneous shedding of cells derived from the lining

of an organ into a cavity, where they can be removed by nonabrasive means. It is the

simplest of the three sampling techniques. To prevent the deterioration of cells by air-

drying or by enzymatic or bacterial actions, the material should be processed

immediately without delay. Alternatively, the use of fixatives, such as alcohol or other

cell preservatives is indicated.

Typical examples are:

The vaginal smear (Pap smear): The cells that accumulate in the vaginal fornix

are derived from several sources: from the squamous epithelium that lines the

vagina and the vaginal portio of the uterine cervix, from the epithelial lining of

the endocervical canal, and from other more distant sources such as the

endometrium. These cells accumulate in the mucoid material and other secretion

from the uterus and the vagina. In addition to the cells derived from the epithelial

linings, the vaginal fornix often contains leukocytes and macrophages that may

3

accumulate there in response to an inflammatory process, and a variety of

microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites that may inhibit the

lower genital tract.

Sputum examination. The sputum is a collection of mucoid material that

contains cells derived from the buccal cavity, the pharynx, larynx, trachea, the

bronchial tree and the pulmonary alveoli; as well as inflammatory cells,

microorganisms, foreign material , etc… The same principle applies to:

Voided urine

Body fluids

Nipple discharge

2- Abrasive Cytology

The purpose of this procedure is to enrich the sample with cells obtained directly from

the surface of the target of interest. Hence, cell specimens are usually obtained

through superficial scraping of the lesion (artificial mechanical desquamation) .

Examples include:

Cervical scraping through Pap smear:

Buccal mucosal smear

Skin scraping of various lesions

Brushing techniques through using various rigid endoscopic and fibroptic

instruments to collect cell samples from the gastrointestinal tract, bronchial tree,

etc…

The Pap Smear Test (Figures 1 - 3)

Is used mainly to detect precancerous and cancerous lesions of the uterine cervix.

Cervical cancers are caused by Human Papilloma Viruses (HPV). These viruses are

tissue-specific DNA viruses that are easily transmissible and highly prevalent. HPV is

the most common sexually transmitted infection; the vast majority of HPV infections

are transient and could be cleared as a result of natural immune responses, becoming

undetectable after 6 to 18 months. However, precancerous lesions can develop if the

infection persists.

HPV induces cellular changes at the basal layer of the squamous epithelium of the

cervix at the transformation zone (pathologically known as “koilocytotic atypia”).

These changes lead to dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and might

4

eventually cause carcinoma. They tend to regress to normal within one year or very

slowly progress to more severe abnormalities and eventually to cervical cancer.

Persistence and progression to cancer may take several years (10-20 years) to develop.

This long natural history makes it liable for early detection and treatment at its

precancerous lesions, if women were screened, diagnosed and treated early.

Thus the Pap smear test is based on the fact that cancer of the cervix is one of the

most preventable cancers, because most of the cellular changes which may lead to

carcinoma can be detected and accordingly treated at an early stage before

progression. .In most cases, cervical carcinoma develops slowly; whereby it passes

into different pre-neoplastic conditions before it reaches the cancer stage.

Mild Dysplasia --► Moderate Dysplasia --► Severe Dysplasia --►

CIN I CIN II CIN III

Carcinoma in Situ --► Carcinoma

CIN III

The CIN classification has almost universally replaced the world health organization

classification, with CIN I, 2 and 3 corresponding to mild, moderate and severe

dysplasia/carcinoma in situ, respectively. The Bethesda Classification system was

introduced in 1988 to facilitate interpretation and management of these precancerous

lesions; whereby LSIL (Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) stands for CIN I

and Koilocytosis while HSIL (High Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion)

corresponds to CIN II and CIN III.

Microscopical examination of the exfoliated cells from the uterine cervix through the

Pap Smear should therefore lead to the detection of these pre-neoplastic lesions in

their earliest stages (i.e., stage of mild dysplasia ). Accordingly, giving the

appropriate treatment will eventually lead to prevention of cervical cancer.

Hence, Pap Smear test is a simple procedure in which a small number of cells are

collected from the cervix and sent to the laboratory where they are tested for anything

abnormal. The cervical scraper introduced by Ayre in 1947 allows a direct sampling

of cells from the squamous epithelium of the cervix and the adjacent endocervical

canal. No anaesthesia is required, and the diagnosis could be obtained within few

minutes. The procedure could be easily carried out in any clinic or specialized lab.

It is recommended that all women between the ages of 18 and 70 years, who have

ever had sexual activity, are advised to have the test every 2 years.

5

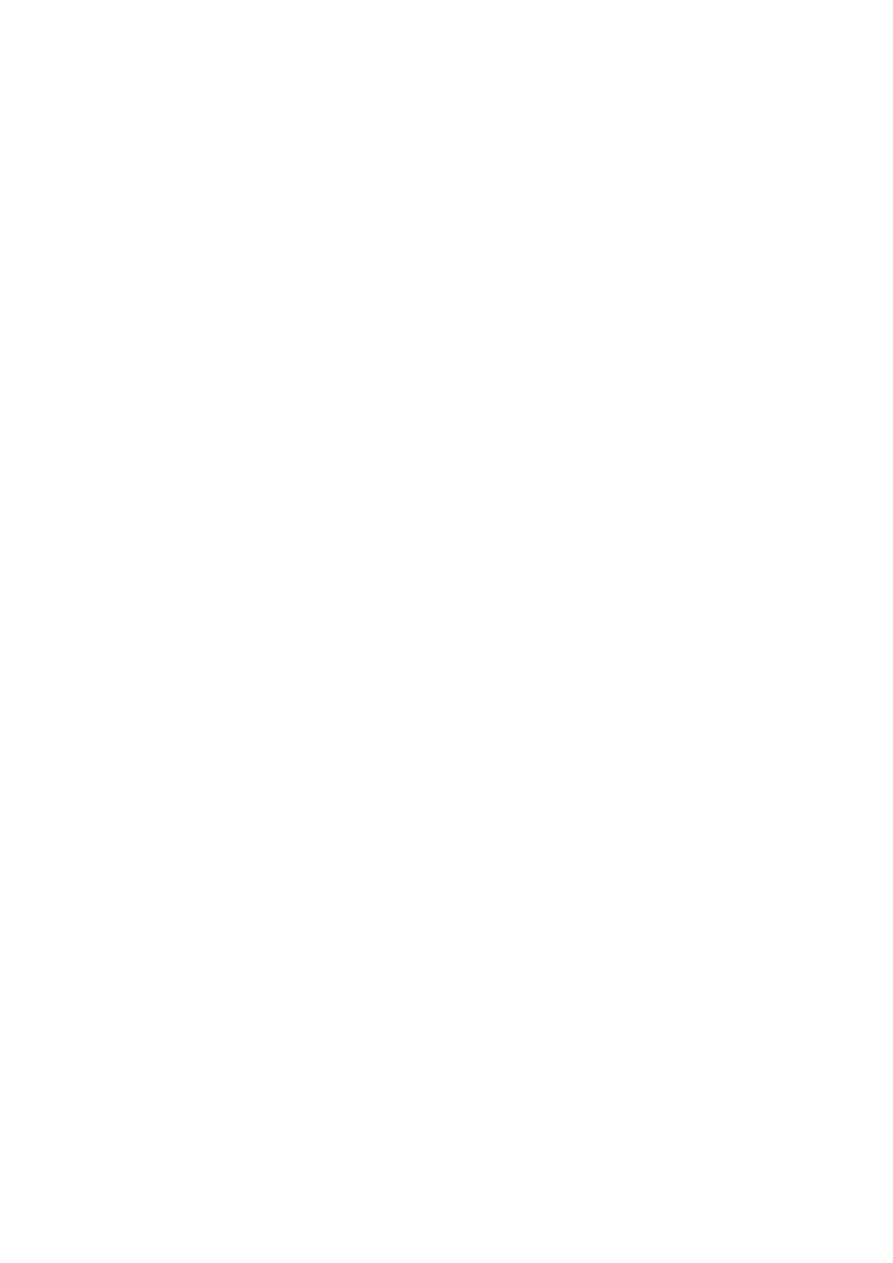

Different Terminologies used for Cytological and Histological Reporting

od Precancerous Lesions of the Uterine Cervix:

The CIN classification has almost universally replaced the World Health Organization

classification, with CIN I, II and III corresponding to mild, moderate and severe

dysplasia/carcinoma in situ, respectively. The Bethesda Classification system was

then introduced in 1988 to facilitate interpretation and management; whereby LSIL

(Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) stands for CIN I and Koilocytosis

while HSIL (High Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) corresponds to CIN II and

CIN III.

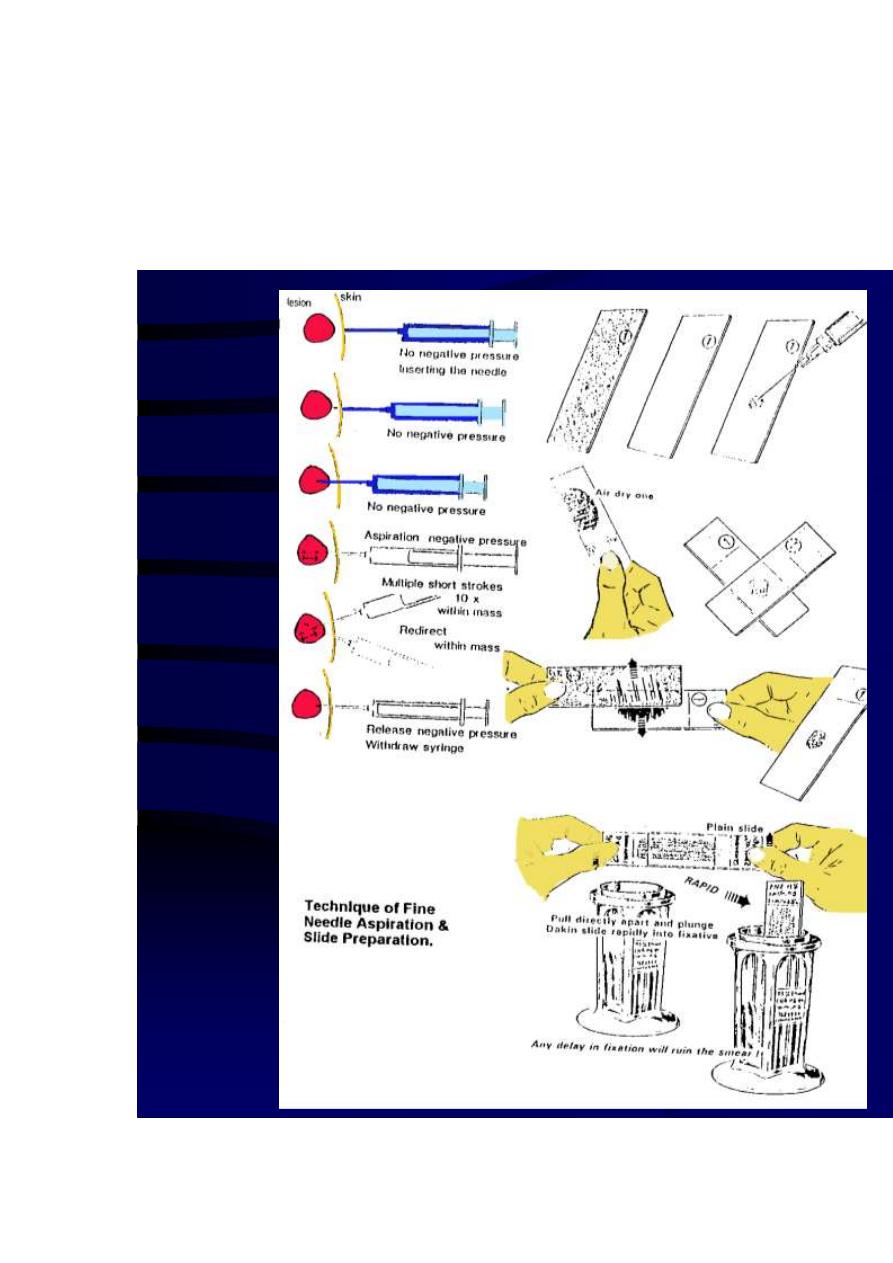

3- Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) (Figure 4)

In general, the definitive diagnosis of any mass can be established by:

Open biopsy

Tissue core needle (Tru-cut) biopsy

Fine needle aspiration biopsy.

Cytological Classification

Histological Classification

Pap

Bethesda system

CIN

WHO descriptive

classifications

Class I

Normal

Normal

Normal

Class II

ASC-US

ASC-H

Atypia

Atypia

Class III

LSIL

CIN I including flat

condyloma

Koilocytosis

Class III

HSIL

CIN II

Moderate dysplasia

Class III

HSIL

CIN III

Severe dysplasia

Class IV

HSIL

CIN III

Carcinoma in situ

Class V

Invasive carcinoma

Invasive carcinoma

Invasive carcinoma

6

Compared to FNA, Tru-cut biopsy is a more traumatic procedure which should be

performed under local anaesthesia. It requires more time and special equipments

that are more expensive. Pain, discomfort and bleeding are common complications.

FNAC, on the other hand, provides many advantages to the surgeons being an easy,

reliable, cost effective diagnostic technique which could give rapid results. The

procedure could be performed in an office setting without anaesthesia. It is usually

not more painful than a venipuncture and can be repeated immediately if the acquired

material is inadequate.

The National Health Service Breast Screening Program (NHSBSP) displayed that

many centers wished to include FNA as an additional test to provide preoperative

diagnosis of breast cancer and to reduce the number of operations for benign breast

diseases.

When reduced to its simplest terms, FNAC consists of:

Using a needle and syringe to remove material from a mass.

Smearing it on a glass slide.

Applying a routine stain.

Examining it under the microscope.

Technique of FNAC:

The skin over the palpable mass (within the breast, lymph node, or any other organ) is

sterilized with an antiseptic. Utilizing the index and the middle finger or the thumb

and the index finger, the mass is localized with the non-dominant hand. With firm

downward pressure on the skin over the mass, it should be compressed against a rib

and stabilized.

Aspirates should be obtained using preferably a 23 gauge, 1 ½ inch disposable needle

mounted on a 10 ml plastic syringe, held by the dominant hand. Larger needles (22

gauges) are used in aspirating material from hard fibrous masses and in cases of

suspected cyst or abscess.

Without using anesthesia, the needle should be gently introduced through the skin

passing to the level of the dominant mass. Having confirmed the position of the

needle within the mass, negative pressure should be created within the syringe by

pulling back the plunger. The needle should move back and forth through the mass, in

different rotational directions using sewing-like-motion. Suction should be maintained

throughout the process by outward pressure of the right thumb on the underside of the

syringe. By this method the needle can cut loose many small pieces of tissue that are

then readily aspirated due to the suction applied by syringe. These to and fro strokes

should be repeated at least 6-8 times. In general most of the aspirations are

terminated when material begins to appear in the needle hub.

7

The following step should be designed to protect the material that has been obtained.

All suction should be released before removing the needle from the mass. This is

accomplished by allowing the syringe plunger to return gently to its resting position.

Then the needle should be withdrawn gently from the mass. To limit haematoma

formation from the site of the puncture, firm pressure should be applied with a piece

of cotton for two minutes.

8

Equipments needed for FNAC procedure:

Syringes

The key feature in a syringe is lightness in weight, adequate in volume, and one hand

control. Modern sterile disposable plastic syringes are perfect for use in FNAC. Most

practitioners use the 10 cc size, while some prefer the 20 cc size (specifically when a

cyst is suspected).

Needles

Several variables should be considered in choosing the proper length and gauge. In

general the length should be at least 1.5 inch (3-8 cm). This is desirable in the breast

because many lesions are found deeper than expected. It has also been demonstrated

that small gauges (22-23) are preferred since they are rigid enough and at the same

time cause less sensation and haematoma. Needles with a plastic hub rather than a

metal hub are preferred as well. This permits the aspirator to monitor the recovery of

tissue, blood or other fluids as they appear in the hub.

Glass Slides

Common routine slides measure 75 mm X 25 mm X 1mm. An important procedure is

slide labeling at the time of sampling. That is why slides which have one frosted end

are preferred. Various substances are used to increase the adherence of specimens to

the slide surface, the most commonly used being albumin.

Fixatives

These are applied to the smears as a spray or by immersion of the slide into a liquid.

The most commonly used is 95 % Ethanol. This inexpensive readily available liquid

provides excellent cytological details. Its only disadvantage is the need to store and

transport slides in a container of liquid and to have them immersed in for at least 20

minutes.

Routine Stains

For cytological diagnosis, fixed material is usually stained by Papanicolaou Stain

(which is preferred) or by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) method. Both employ one

of the Hematoxylins for staining of the nuclei. This dye colors the nucleic acids as a

dark purple blue color. The counter staining with Eosin is designed to show

cytoplasmic characteristics. With the Pap stain one hallmark is the use of Orange-G,

which stains cytoplasmic keratin with a bright orange color.

Air-dried smears on the other hand are usually stained by any Romanowsky stains,

which are various combinations of methylene blue and its breakdown products (Azure

A, B, &C) with Eosin. Most rely on Methanol fixation.

Papanicolaou Stain

All slides should be wet fixed within 95% or absolute Ethanol before staining:

95% ethanol 10 dips

80% ethanol 10 dips

70% ethanol 10 dips

50% ethanol 10 dips

Distilled water 10 dips

9

Hematoxylin Stain 1-2 min.

Running Tap water 10 dips

50% ethanol 10 dips

70% ethanol 10 dips

80% ethanol 10 dips

95% ethanol 10 dips

Orange-G Stain 2 min.

95% ethanol 10 dips

Eosin Stain 2 min.

95% ethanol 10 dips

95% ethanol 10 dips

Absolute ethanol 10 dips

Absolute ethanol: Xylol (50:50 mixture) 5 min.

Xylol 20 min.

Mount with Canada Balsam

Pitfalls to Reliable Results from FNAC

No mass

Vague mass

Mass being too small ( less than 1 cm )

Mass being too deep

Gross blood into the syringe (i.e., RBCs can mask the picture)

Scanty cellularity in the aspirated mass

Dense fibrosis

Gross fluid into th

Indications for Cytopathology

1- Differentiation between benign and malignant lesions.

2- Diagnosis of malignancy and its type, as well as the identification of the

neoplastic cells in primary, metastatic (secondary) or recurrent tumors.

3- Diagnosis of premalignant diseases: i.e., detection of precancerous or

dysplastic cellular changes (figure 5). As explained earlier, dysplasia may be

graded as mild, moderate and severe. In the uterine cervix for example, those

lesions could be eliminated by treatment of the associated inflammation and

causative pathogen or by excision of the lesion.

4- Detection of inflammation and certain types of pathogenic agents: i.e., the

cytologist could prove that the cause of vaginal secretion is vaginitis due to

Trichomonus vaginalis, Moniliasis or the cytology could show changes

suggestive of Human Papilloma Virus infection (HPV – Figure 6). Similarly

11

the cause of cystitis may be related to bilharziasis ( through the detection of

Bilharzial ova in smears of urine samples).

5- Study of the hormonal patterns and evaluation of the gonadal hormonal

activity: through the examination of the squamous cells in vaginal smears;

which are under the influence of ovarian hormones (figure 7).

6- Follow-up and monitoring of response to chemotherapy and irradiation; the

latter producing certain cellular features which could be diagnostic on

cytologic examination.

7- The identification of sex chromosome: if a newborn presents with ambiguous

genitalia, one can not tell whether the sex is male or female. The presence of a

dark dot attached to the nuclear membrane from inside (Barr body +ve)

indicates that a sex chromosome is present, i.e., the genotype of the baby is

XX (♀). Conversely the absence of this Barr body indicates that there is no X

chromosome and accordingly the newborn is genotypically a male ((XY ♂).

8- Tumour markers study on cytological specimens.

Cytological Criteria of Malignancy

(Figures 8 – 12)

A) Nuclear Changes:

Nuclear hypertrophy: nuclear enlargement that leads to increased N/C ratio.

Nuclear size variation

Nuclear shape variation

Hyperchromatism and chromatin irregularity: refers to increased chromatin

materials. In malignant cells the chromatin is not evenly distributed within the

nucleus; it is also distributed as coarse, clumps. This in contradistinction to

normal cells, which have evenly distributed chromatin.

Multinucleation: malignant cells may contain more than one nucleus. However,

some normal cells such as hepatocytes and histiocytes may contain more than

one nucleus. Multinucleated malignant cells differ from nonmalignant

multinucleated cells by the fact that the nuclei of malignant cells are unequal

in size (in contrast to that of normal cells).

Irregularity of the nuclear membrane.

11

Irregular and prominent nucleoli: giant nucleoli or multiple nucleoli may be

present that differ in their sizes and shapes. It should be remembered, however,

that normal columnar and goblet cells may contain 2 nucleoli.

B) Cytoplasmic Changes:

Scantiness of cytoplasm: in consequence to the high N/C ratio.

Cytoplasmic boundries: sharp and distinct in Squamous cell carcinomas and

indistinct in undifferentiated carcinomas.

Variation in size .

Variation in Shape.

Cytoplasmic staining: deep orange in keratinizing squamous carcinomas

or basophoilic in immature poorly differentiated carcinomas.

Cytoplasmic inclusions: e.g. melanin pigments in melanoma.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear membrane relationship: cytoplasmic borders of

malignant cells could be tightly molded against the nucleus, touching it in

more than one place.

C) Changes in Malignant Cells as a Group:

Cellular phagocytosis or Cannibalism: i.e., one cell appearing to be contained

in a vacuole of the cytoplasm of another epithelial cell; indicating rapid

growth of cells within a narrow cavity.

Variation in the size and shape of the cell clusters or sheets.

Lack of cellular adhesion: due to abnormalities in the desmosomes.

Abnormal mitosis: malignant nuclei may show multiple poles e.g. three poles

(tripolar mitosis; triploidy) or four poles (tetrapolar mitosis; tetraploidy). This

is abnormal since normal mitosis has two poles (bipolar). Thus normal cells

show euploid or diploid pattern on flow or image cytometry whereas

malignant cells may show abnormal aneuploid patterns.

Bloody background: fresh blood is meaningless, but malignancy is suspected

when the blood is old, partially ingested by histeocytes or present within a

specimen which is obtained without trauma.

Foreign cellular structures: e.g. psammoma bodies in a routine vaginal smear.

Degeneration and inflammation as a result of erosion or necrosis within the

malignant tumour which could indicate invasion (i.e., tumour diathesis).

12

Perhaps the best demonstrable tool to observe the various types of malignant cells

which could be encountered cytologically is through studying the different variants of

Bronchogenic Carcinoma. A routine recommendation for these patients is the

examination of three successive early morning sputum samples.

Histologically, there are four major different types of bronchial cell carcinoma could

be recognized on cytological examination:

1. Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Figure 9)

Is the most common and easiest type to be diagnosed by cytologic examination of

sputum because of its central position within the bronchial tree. Cytologically, most

malignant cells exfoliate singly but some may be observed in clusters or sheets. Cells

often assume variable sizes and shapes; could be amoeboid in shape, assuming

pseudopod-like projections. Spindle or tadpole cells could be also detected. The

background is usually obscured by necrotic debries, mucous and RBCs (tumour

diathesis).

The cytoplasm is abundant, dense and granular with a glassy orange appearance in

well-differentiated types due to the presence of keratin (stained by Orane G).

Anucleated deep orange squames may be evident in long standing cases. The nucleus

may show nuclear size and shape variation with irregularity of the nuclear membrane.

Marked hyperchromasia is often present; the nuclei appearing very dark or pyknotic.

Cannibalism is common. Red prominent nucleoli could be present.

2. Adeno Carcinoma (Figure 10)

Usually periphral in position. Cells exfoliate in clusters, sheets or acini; rarely singly.

They are often round, oval and irregular in shape. Cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed

in well-differentiated types due to the presence of mucous droplets. Large vacuoles

may push or compress the nucleus to one side giving an irregular moon-shaped

appearance: signet-ring pattern. Neutrophils maybe seen within these vacuoles.

Nuclei are often round or oval with moderate hyperchromatism and irregular nuclear

membrane. Single or multiple diagnostic nucleoli are usually found. Multinucleatin

may occur. Cells stain positive with PAS stain (due to the presence of mucin).

3. Undifferentiated Small Cell Carcinoma (Figure 11)

The WHO classification recognizes three histological subtypes:

- Oat cell carcinoma.

13

- Small cell carcinoma – intermediate type.

- Combined Oat cell carcinoma (seen with foci of squamous cell

and/or adenocarcinoma).

The cellular morphology of small cell carcinoma varies with the method of specimen

collection. In sputum, the exfoliated cells are often small in association with long

strands of mucous. Dark lines of elongated compact masses of numerous small

hyperchromatic neoplastic cells are seen with satellite single cells scattered around.

The nucleus could be degenerated and pyknotic. In brushings and FNA samples, cells

are usually better preserved, appearing larger and displaying more variations in

nuclear chromasia and chromatin patterns.

4. Undifferentiated Large Cell Carcinoma (Figure 12)

These are epithelial tumours comprised of malignant cells with large nuclei and

prominent nucleoli that show no evidence of squamous, glandular or small cell

differentiation. In the WHO classification, two variants are recognized:

- Giant cell carcinoma which contains a prominant component of highly

pleomorphic multinucleated cells which maybe actively phagocytic. The

hyperchromatic nuclei shows irregular chromatin clumping and large

prominent macronucleoli.

- Clear cell carcinoma which is a rare variant composed of large cells with

clear or foamy cytoplasm without mucin.

In general, during the evaluation of a smear, the cytopathologist should look for the

following changes

Modification of the normal nuclear and cytoplasmic cells.

Maturation status (i.e., observe whether the cells are mature or immature.)

The quantity of the cells (hypo- or hyper-cellular) and their mode of

desquamation (clusters, sheets or scattered individually).

Smear background (i.e., the presence of leukocytes, histiocytes, RBCs,

necrotic cells and protein deposits)..

14