Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Digestive Secretion from Pancreas and Liver

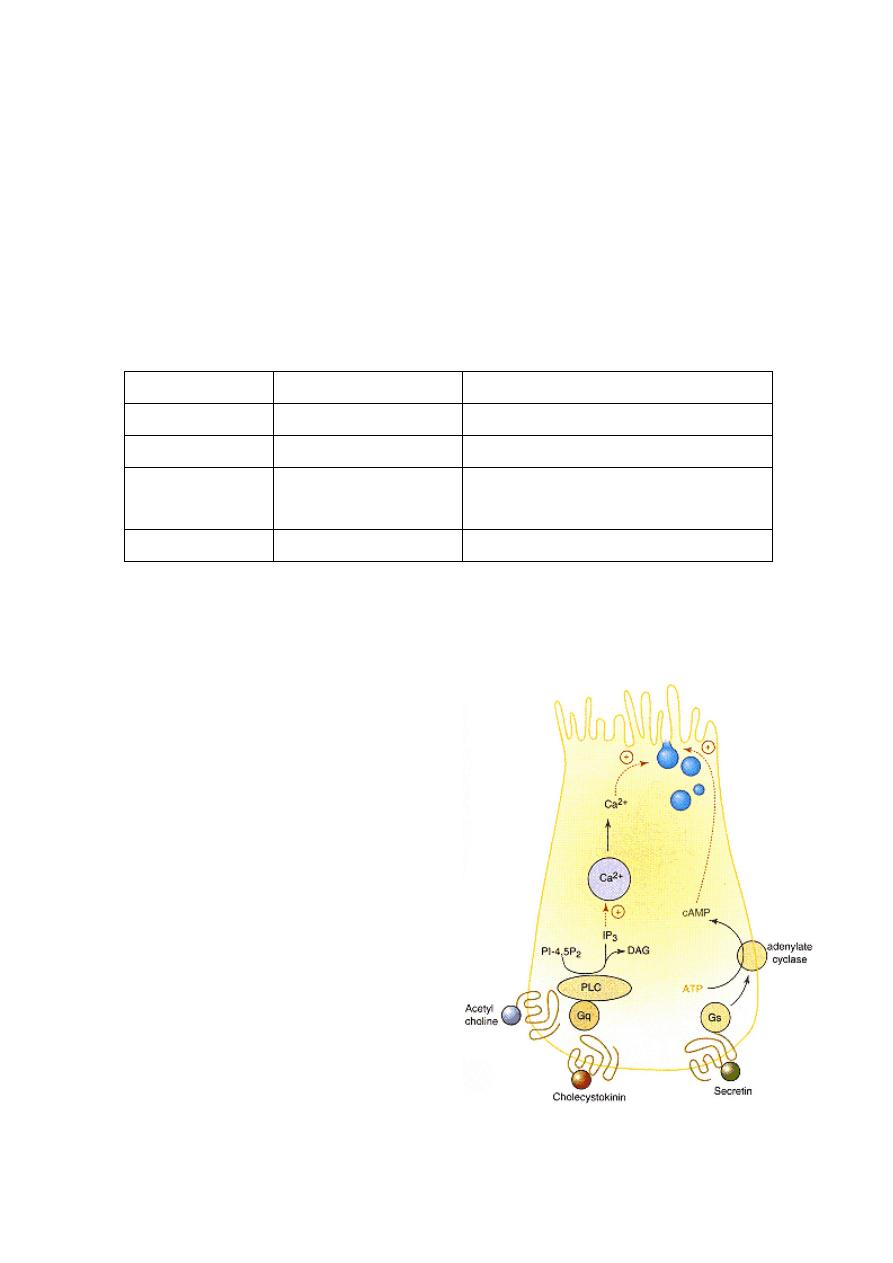

Regulation of Secretion Occurs through Secretagogues

The processes involved in the secretion of enzymes and electrolytes are regulated and

coordinated. Elaboration of electrolytes and fluids simultaneously with that of enzymes is

required to flush any discharged digestive enzymes out of the gland into the

gastrointestinal lumen. The physiological regulation of secretion occurs through

secretagogues that interact with receptors on the surface of the exocrine cells.

Organ

Secretion

secretagogue

Salivary gland

amylase

Acetylcholine

Stomach

HCl, pepsinogen

Acetylcholine, histamine, gastrin

Pancreas acini

digestive enzymes

Acetylcholine, cholecystokinin

(secretin)

Pancreas duct

NaHCO

3

, NaCl

Secretin

Neurotransmitters, hormones, pharmacological agents, and certain bacterial toxins can be

secretagogues. Different exocrine cells, for example, in different glands, usually possess

different sets of receptors. Binding of the

secretagogues to receptors sets off a chain of

signaling events that ends with fusion of

zymogen granules with the plasma

membrane.

Two major signaling pathways have been

identified:

(1) activation of phosphatidylinositol-specific

phospholipase C with liberation of inositol

1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol ; in turn,

triggering Ca

2+

release into the cytosol and

activation of protein kinase C, respectively;

and

(2) activation of adenylate or guanylate

cyclase, resulting in elevated cAMP or cGMP

levels, respectively . Secretion can be stimulated through either pathway.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

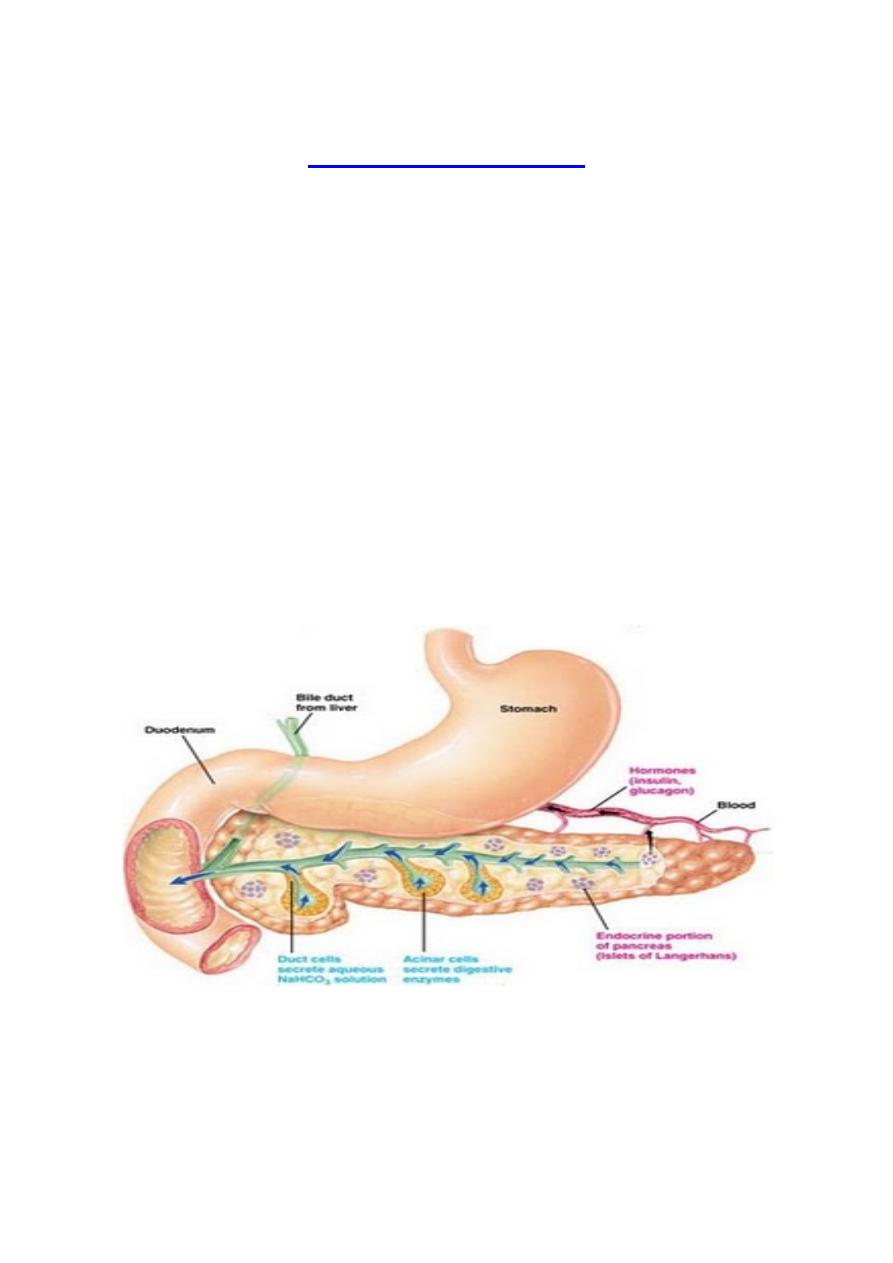

The Pancreas

The pancreas, not the stomach, is the major organ that synthesizes and secretes the large

amounts of enzymes needed for digestion. Thus the pancreas plays a vital role in accomplishing

the followings:

• Acid must be quickly and efficiently neutralized to prevent damage to the duodenal mucosa

• Macromolecular nutrients - proteins, fats and starch - must be broken down much further before their

constituents can be absorbed through the mucosa into blood.

The pancreatic enzymes together with bile are poured into the lumen of the second

(descending) part of the duodenum, so that the bulk of the intraluminal digestion occurs distal

to this site in the small intestine. However, pancreatic enzymes cannot completely digest all

nutrients to forms that can be absorbed. Even after exhaustive contact with pancreatic

enzymes, a substantial portion of carbohydrates and amino acids are present as dimers and

oligomers that depend for final digestion on enzymes present on the luminal surface or within

the chief epithelial cells that line the lumen of the small intestine (enterocytes).

Exocrine Secretions of the Pancreas

Pancreatic juice is composed of two secretory products critical to proper digestion: digestive

enzymes and bicarbonate. The enzymes are synthesized and secreted from the exocrine acinar

cells, whereas bicarbonate is secreted from the epithelial cells lining small pancreatic ducts.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

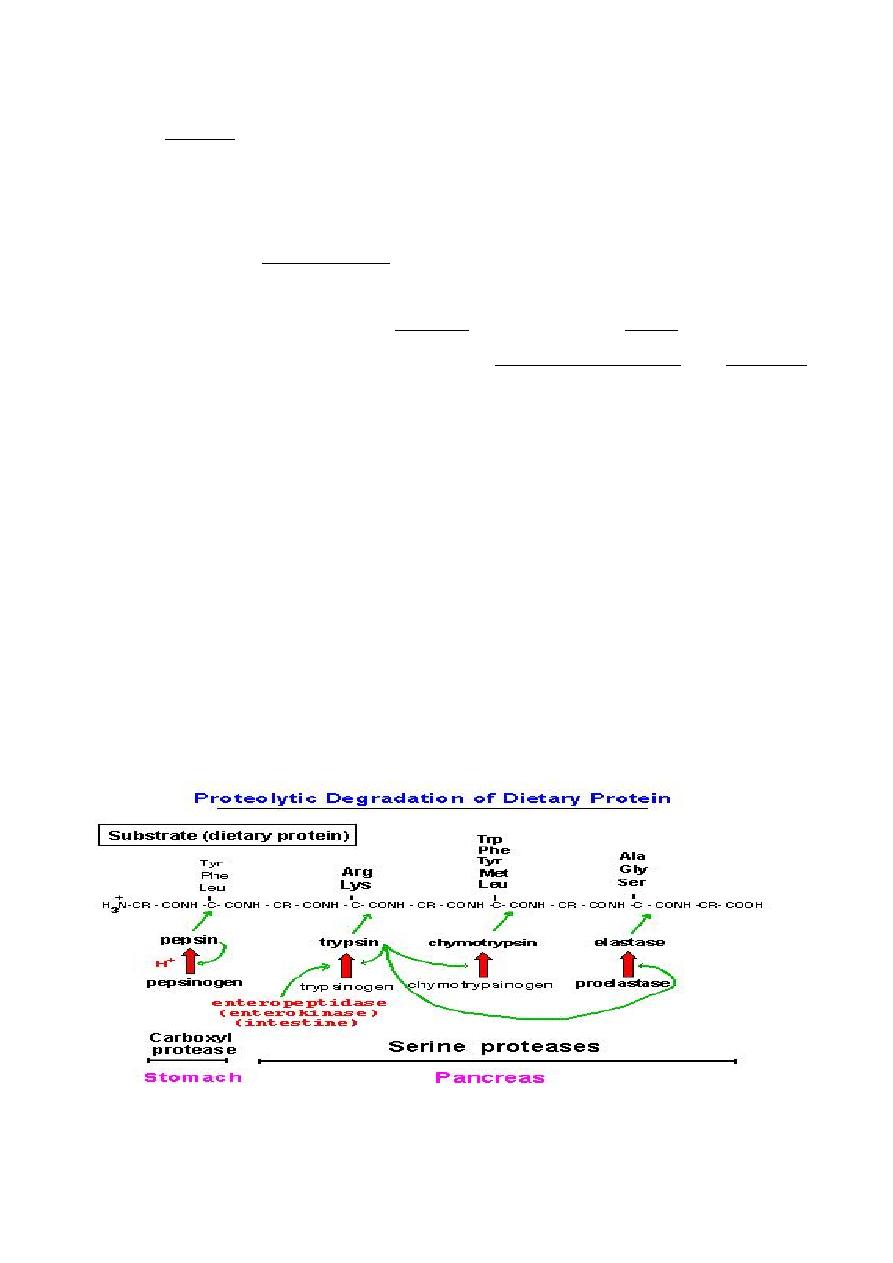

1. Digestive Enzymes:

a.

Proteases

Digestion of proteins is initiated by pepsin in the stomach, but the bulk of protein digestion is due

to the pancreatic proteases. Several proteases are synthesized in the pancreas and secreted

into the lumen of the small intestine. The two major pancreatic proteases are trypsin and

chymotrypsin both are endopeptidases, which are synthesized and packaged into secretory

vesicles as the inactive proenzymes trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen.

•

Trypsin: Cleaves peptide bonds on the C-terminal side of arginines and lysines.

•

Chymotrypsin: Cuts on the C-terminal side of tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan

residues (the same bonds as pepsin, whose action ceases when the NaHCOs raises the pH

of the intestinal contents).

Once trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen are released into the lumen of the small intestine, they

must be converted into their active forms in order to digest proteins, Trypsinogen is activated by

the enzyme enterokinase, which is embedded in the intestinal mucosa.

Once trypsin is formed, it activates chymotrypsinogen, as well as additional molecules of trypsinogen.

The net result is a rather explosive appearance of active protease once the pancreatic secretions

reach the small intestine.

Trypsin and chymotrypsin digest proteins into peptides and peptides into smaller peptides, but they

cannot digest proteins and peptides to single amino acids. Some of the other proteases from the

pancreas, for instance carboxypeptidase (exopeptidase) (This enzyme removes, one by one, the

amino acids at the C-terminal of peptides). But the final digestion of peptides into amino acids is largely the

effect of peptidases in small intestinal epithelial cells.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

b.

Pancreatic Lipase

The major form of dietary fat is triglyceride, or neutral lipid. A triglyceride molecule cannot be

directly absorbed across the intestinal mucosa. It must first be digested into a 2-monoglyceride

and two free fatty acids. The enzyme that performs this hydrolysis is pancreatic lipase.

Sufficient quantities of bile salts must also be present in the lumen of the intestine in order for

lipase to efficiently digest dietary triglyceride and for the resulting fatty acids and

monoglyceride to be absorbed. This means that normal digestion and absorption of dietary

fat is critically dependent on secretions from both the pancreas and liver.

Pancreatic lipase has recently been in the limelight as a target for management of obesity.

The drug orlistat (Xenical) is a pancreatic lipase inhibitor that interferes with digestion of

triglyceride and thereby reduces absorption of dietary fat. Clinical trials support the

contention that inhibiting lipase can lead to significant reductions in body weight in some

patients.

c.

Amylase

The major dietary carbohydrate for many species is starch, a storage form of glucose in plants. Amylase

is the enzyme that hydrolyses starch to maltose (a glucose-glucose disaccharide), as well as the

trisaccharide maltotriose and small branchpoints fragments called dextrins.

d.

Other Pancreatic Enzymes

In addition to the proteases, lipase and amylase, the pancreas produces a host of other digestive

enzymes, including nucleases, gelatinase and elastase.

• Nucleases. These hydrolyze ingested nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) into their component

nucleotides.

• Elastase: Cuts peptide bonds next to small, uncharged side chains such as those of alanine

and serine.

2. Bicarbonate and Water

Epithelial cells in pancreatic ducts are the source of the bicarbonate and water

secreted by the pancreas. The mechanism of bicarbonate secretion is essentially the

same as for acid secretion parietal cells and is dependent on the enzyme

carbonic anhydrase. In pancreatic duct cells, the bicarbonate is secreted into the

lumen of the duct and hence into pancreatic juice.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Control of Pancreatic Exocrine Secretion

Secretion from the exocrine pancreas is regulated by both neural and endocrine controls.

During interdigestive periods, very little secretion takes place, but as food enters the

stomach and, a little later, chyme flows into the small intestine, pancreatic secretion is

strongly stimulated.

•

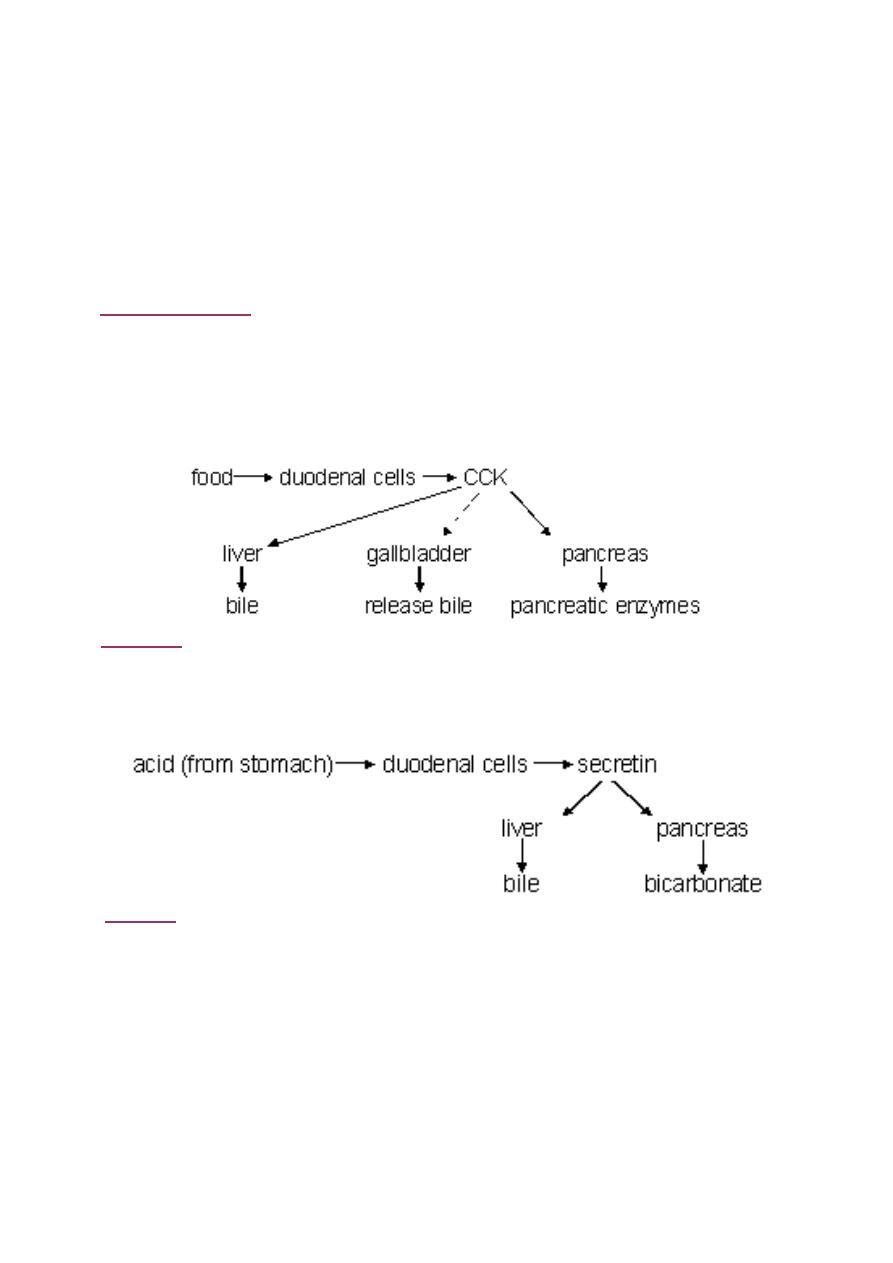

Cholecystokinin

: This hormone is synthesized and secreted by enteric endocrine

cells located in the duodenum. Its secretion is strongly stimulated by the presence of

partially digested proteins and fats in the small intestine. As chyme floods into the

small intestine, cholecystokinin is released into blood and binds to receptors on

pancreatic acinar cells, ordering them to secrete large quantities of digestive

enzymes. It also stimulates the gallbladder to release bile and the pancreas to

produce pancreatic enzymes.

•

Secretin

: This hormone is secreted in response to acid in the duodenum. The

predominant effect of secretin on the pancreas is to stimulate duct cells to

secrete water and bicarbonate. As soon as this occurs, the enzymes secreted by

the acinar cells are flushed out of the pancreas, through the pancreatic duct

into the duodenum. It also stimulates the liver to secrete bile.

•

Gastrin

: This hormone, which is very similar to cholecystokinin, is secreted in

large amounts by the stomach in response to gastric distention and irritation, in

addition to stimulating acid secretion by the parietal cell; gastrin stimulates

pancreatic acinar cells to secrete digestive enzymes.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

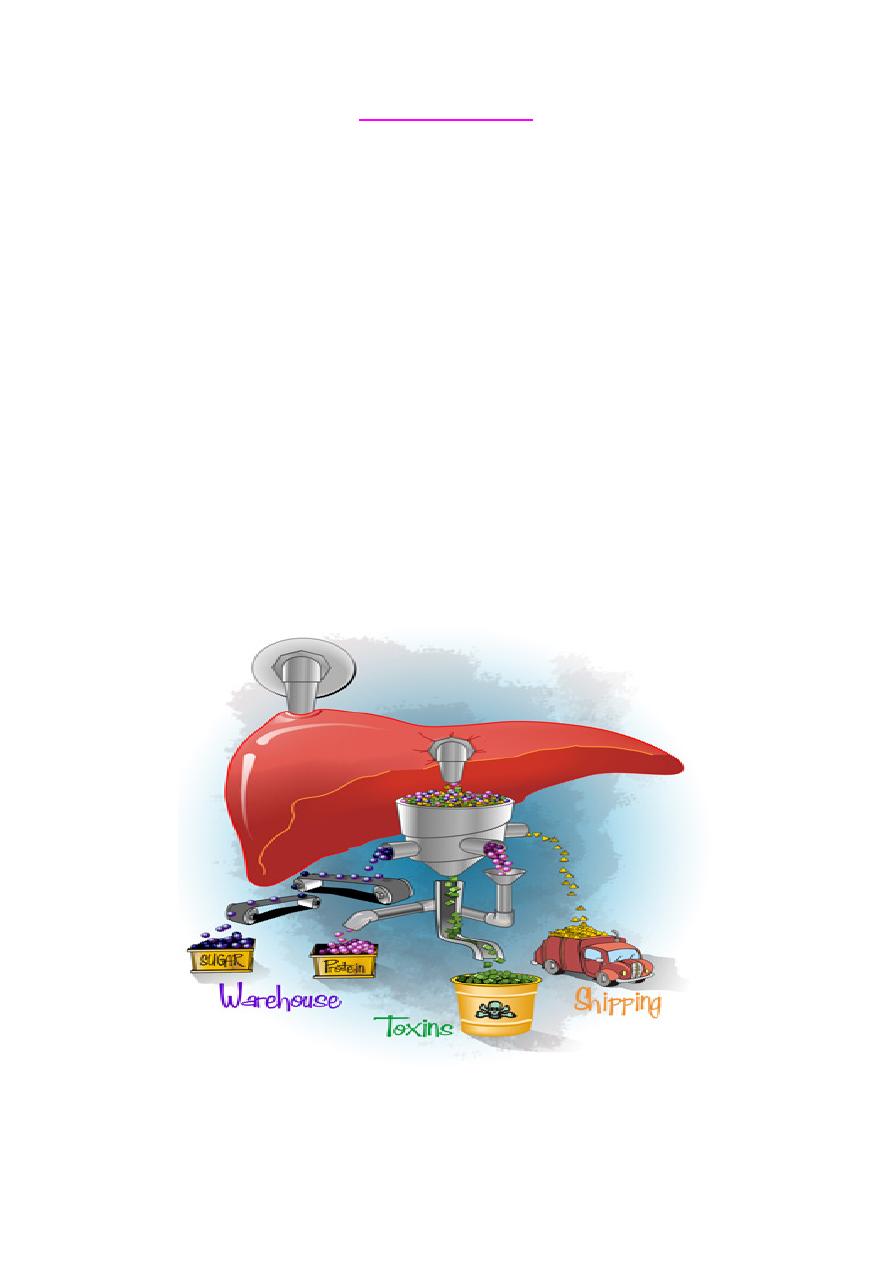

The Liver

The liver is the largest gland in the body and performs an astonishingly large

number of tasks that impact all body systems. One consequence of this complexity is

that hepatic disease has widespread effects on virtually all other organ systems.

The three fundamental roles of the liver are:

1.

Vascular functions

: including formation of lymph and hepatic phagocytic system.

2.

Metabolic achievements

in control of synthesis and utilization of

carbohydrates, lipids and proteins.

3.

Secretory and excretory functions

, particularly with respect to the synthesis

of secretion of bile.

The latter is the only one of the three that directly affects digestion - the liver,

through its biliary tract, secretes bile acids into the small intestine where they

assume a critical role in the digestion and absorption of dietary lipids.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Secretion of Bile and the Role of Bile Acids in Digestion

Bile is a complex fluid containing water, electrolytes and a battery of organic

molecules including bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and bilirubin that flows

through the biliary tract into the small intestine. There are two fundamentally

important functions of bile in all species:

• Bile contains bile acids, which are critical for digestion and absorption

of fats and fat-soluble vitamins in the small intestine.

•

Many waste products are eliminated from the body by secretion into bile

and elimination in feces.

The secretion of bile can be considered to occur in two stages:

• Initially, hepatocytes secrete bile into canaliculi, from which it flows into bile

ducts. This hepatic bile contains large quantities of bile acids, cholesterol and

other organic molecules.

• As bile flows through the bile ducts it is modified by addition of a watery,

bicarbonate-rich secretion from ductal epithelial cells.

In humans: the gall bladder stores and concentrates bile during the fasting state.

Typically, bile is concentrated five-fold in the gall bladder by absorption of water and

small electrolytes - virtually all of the organic molecules are retained.

Secretion into bile is a major route for eliminating cholesterol. Free cholesterol is

virtually insoluble in aqueous solutions, but in bile, it is made soluble by bile acids

and lipids like lethicin. Gallstones (Cholelithiasis) most of which are composed

predominantly of cholesterol, result from processes that allow cholesterol to

precipitate from solution in bile.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Role of Bile Acids in Fat Digestion and Absorption

Bile salts are formed in the hepatocytes by a series of enzymatic steps that convert

cholesterol to cholic or chenodeoxycholic acids. The rate limiting step is

hydroxylation at the 7-alpha position. These reactions include the activity of 8

enzymes belonging to either monooxygenase or dehydrogenase enzyme

classes.

The most abundant bile acids (primary bile acids ) are:

1. chenodeoxycholic acid (45%) and

2. cholic acid (31%).

Within the intestines the primary bile acids are acted upon by bacteria and

converted to the secondary bile acids, identified as

1. deoxycholate (from cholate) and

2. lithocholate (from chenodeoxycholate).

Chenodiol is a natural bile acid that blocks production of cholesterol . Chenodiol

(Chenix), is used to dissolve gallstones in patients who cannot tolerate surgery.

This

action leads to gradual dissolution of cholesterol gallstones.

Synthesis of bile acids is one of the predominant mechanisms for the excretion of

excess cholesterol. However, the excretion of cholesterol in the form of bile acids is

insufficient to compensate for an excess dietary intake of cholesterol.

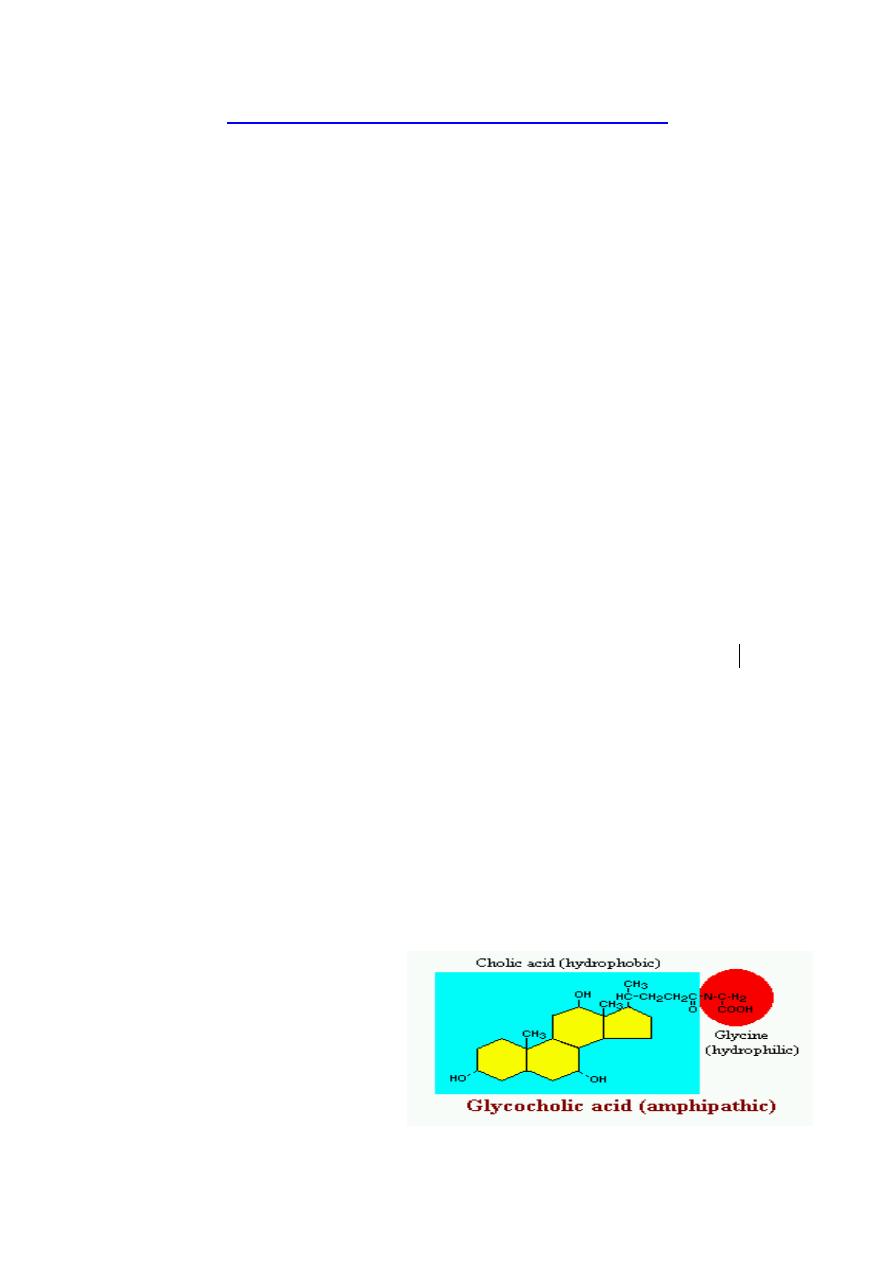

Bile acids are conjugated with glycine or taurine and secreted as Na

+

(or K

+

) salts.

Conjugation causes a decrease in their pKa values, making them more water-

soluble.

Bile acids are carried from the liver

through ducts to the gallbladder,

where they are stored for future use.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

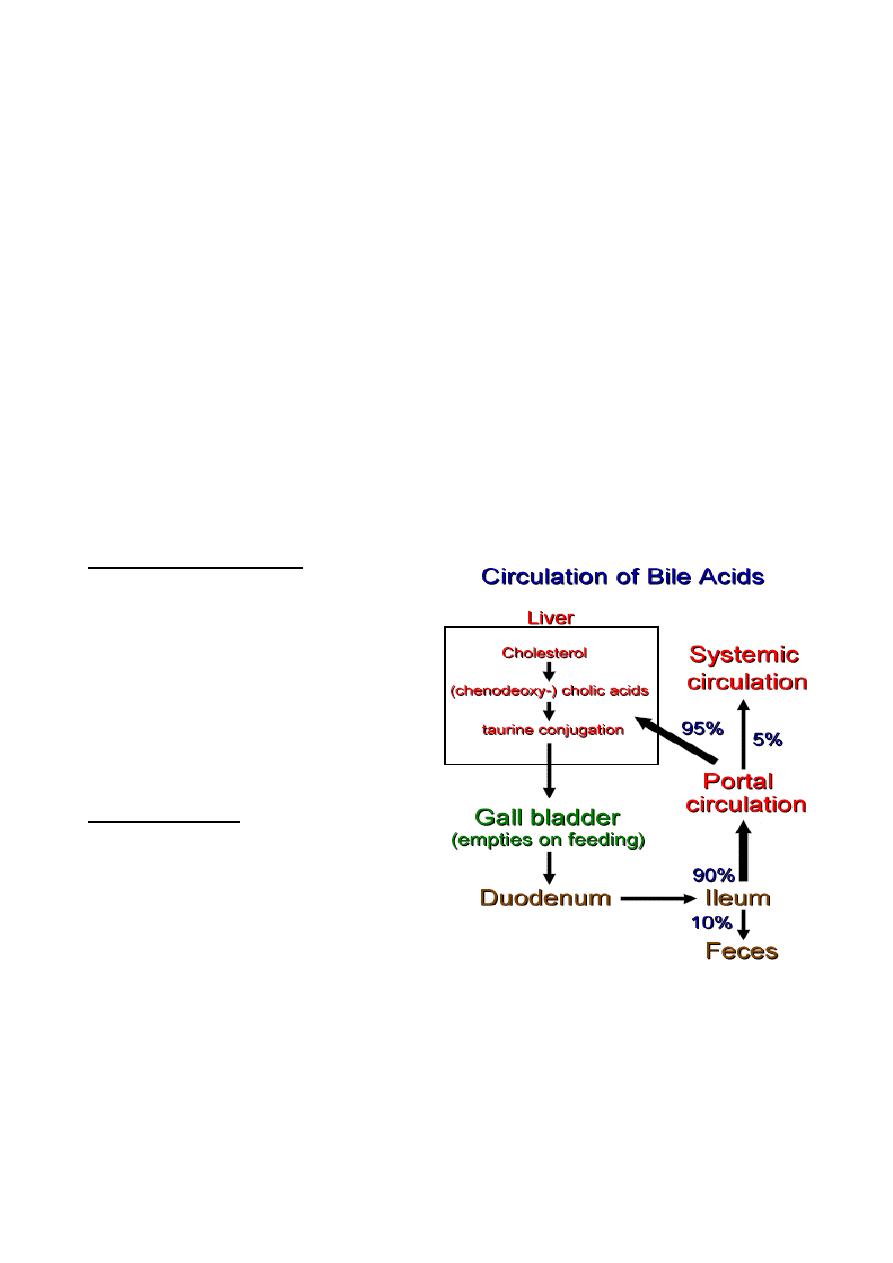

The ultimate fate of bile acids is secretion into the intestine, where they aid in the

emulsification of dietary lipids. In the gut the glycine and taurine residues are removed

and the bile acids are either excreted (only a small percentage) or reabsorbed by the

gut and returned to the liver. This process of secretion from the liver to the gallbladder,

to the intestines and finally reabsorbtion is termed the enterohepatic circulation.

Enterohepatic Recirculation

After the bile acids has been released into the small intestine via the bile duct to play an

integral role in the absorption of dietary lipids and lipid soluble vitamins. More than

90% of the bile salts are actively reabsorbed (by a sodium-dependent co-

transport process) from the ileum into the hepatic-portal circulation from where they are

cleared and resecreted by the liver to once again be stored in the gall bladder. This

secretion/reabsorption cycle is called the Enterohepatic Circulation.

Systemic circulation: supplies

nourishment to all of the tissue located

throughout your body, with the exception

of the heart and lungs because they have

their own systems. Systemic circulation is

a major part of the overall circulatory

system.

Portal circulation: Blood from the gut

and spleen flow to and through the liver

before returning to the right side of the

heart. This is called the portal circulation

and the large vein through which blood is

brought to the liver is called the portal vein.

The net effect of this enterohepatic recirculation is that each bile salt molecule is

reused about 20 times, often two or three times during a single digestive phase.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Note: liver disease can dramatically alter this pattern of recirculation - for instance, sick

hepatocytes have decreased ability to extract bile acids from portal blood and damage to the

canalicular system can result in escape of bile acids into the systemic circulation. Assay of

systemic levels of bile acids is used clinically as a sensitive indicator of hepatic disease.

Bile acids contain both hydrophobic (lipid soluble) and polar (hydrophilic)

faces. The amphipathic nature enables bile acids to carry out two important

functions:

1. Emulsification of lipid aggregates

: Bile acids have detergent action

on particles of dietary fat, which causes fat globules to break down

or be emulsified into minute, microscopic droplets. Emulsification is not

digestion per se, but is of importance because it greatly increases the

surface area of fat, making it available for digestion by lipases, which

cannot access the inside of lipid droplets.

2. Solubilization and transport of lipids in an aqueous environment

: Bile

acids are lipid carriers and are able to solubilize many lipids by

forming micelles - aggregates of lipids such as fatty acids, cholesterol

and monoglycerides - that remain suspended in water. Bile acids are

also critical for transport and absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins.

Clinical Significance of Bile Acid Synthesis

Bile acids perform four physiologically significant functions:

1. Their synthesis and subsequent excretion in the feces represent the only

significant mechanism for the elimination of excess cholesterol.

2. Bile acids and phospholipids solubilize cholesterol in the bile, thereby

preventing the precipitation of cholesterol in the gallbladder.

3. They facilitate the digestion of dietary triacylglycerols by acting as

emulsifying agents that render fats accessible to pancreatic lipases.

4. They facilitate the intestinal absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Lecture 3

Thursday 27/9/2012

Dr Hedef D.El-Yassin

ِ◌ ِ◌

Prof.

2012

Pattern and Control of Bile Secretion

The flow of bile is lowest during fasting, and a majority of that is diverted into the

gallbladder for concentration. When chyme from an ingested meal enters the

small intestine, acid and partially digested fats and proteins stimulate secretion

of cholecystokinin and secretin. These enteric hormones have important effects

on pancreatic exocrine secretion. They are both also important for secretion and

flow of bile:

1.

Cholecystokinin:

The name of this hormone describes its effect on the

biliary system - cholecysto = gallbladder and kinin = movement. The

most potent stimulus for release of cholecystokinin is the presence of fat in

the duodenum. Once released, it stimulates contractions of the gallbladder

and common bile duct, resulting in delivery of bile into the gut.

2.

Secretin

: This hormone is secreted in response to acid in the duodenum.

Its effect on the biliary system is very similar to what was seen in the

pancreas - it simulates biliary duct cells to secrete bicarbonate and water,

which expands the volume of bile and increases its flow out into the intestine.