Dr: Muhi Lec :3

Pediatric

BRONCHIAL ASTHMA

IN CHILDREN

Total : 37

Lec : 3

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

BRONCHIAL ASTHMA IN CHILDREN

Prof.Dr. Muhi K. Aljanabi

MRCPCH; DCH; FICMS

Consultant Pediatric Pulmonologist

OBJECTIVES

1. Understand the natural history of asthma during childhood.

2. Be familiar with the key features of history and examination that support a diagnosis of

asthma.

3. Be familiar with the other common clinical conditions that can mimic asthma

(gastroesophageal reflux, cystic fibrosis, viral induced wheezing, bronchiolitis, croup).

4. Be able to manage an acute exacerbation of asthma.

5. Know the details of the drugs used to treat acute and chronic asthma and understand their

mechanism of action.

6. Know the guidelines for the management of asthma.

7. Be able to advise parents about how to care for a child with asthma.

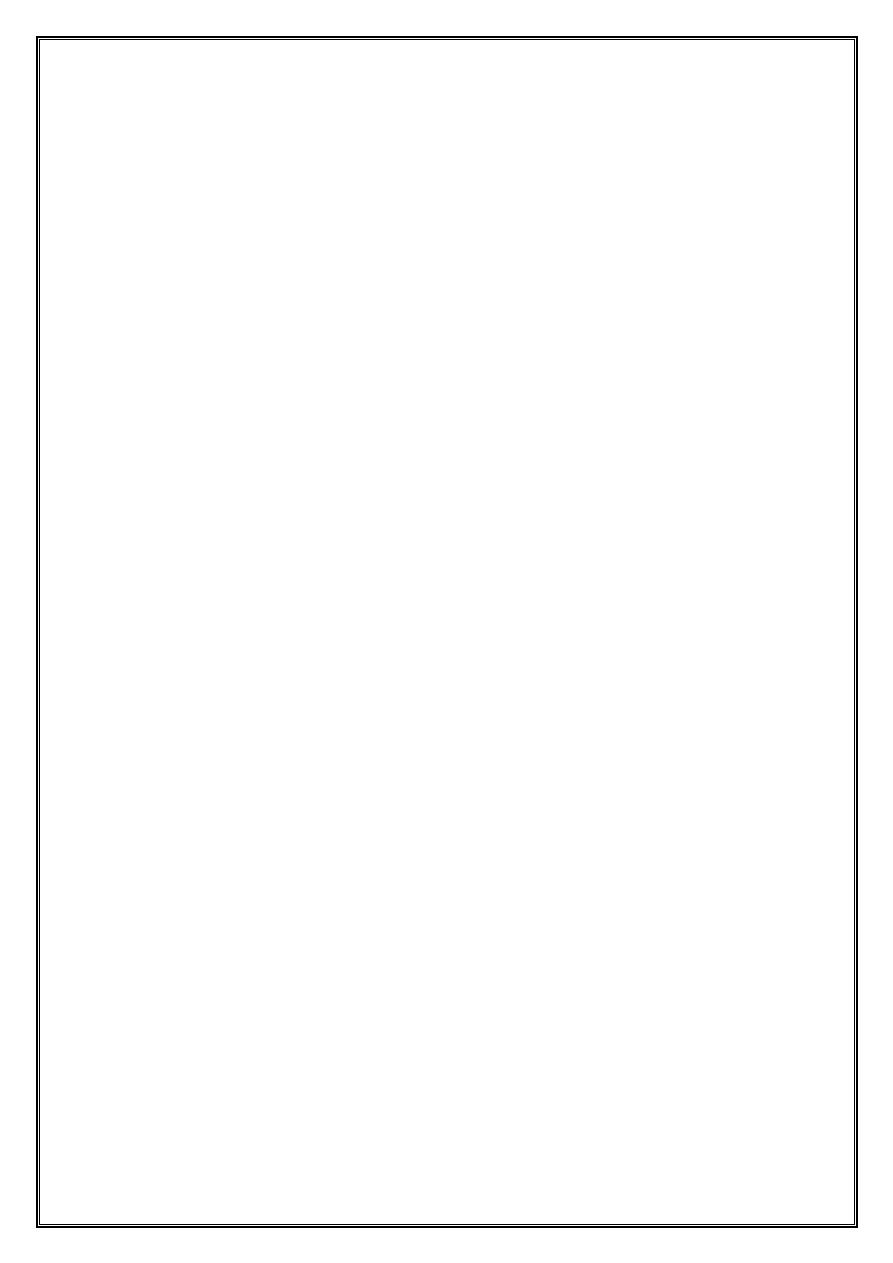

DEFINITION

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the lung airways resulting in episodic

airflow obstruction.

This chronic inflammation heightens the “twitchiness” of the airways—airways

hyperresponsiveness (AHR)—to provocative exposures.

ETIOLOGY

1- Genetics:

More than 22 loci on 15 autosomal chromosomes have been linked to asthma.

2- Environment :

Common respiratory viruses.

Indoor and home allergen exposures in sensitized individuals

Environmental tobacco smoke and air pollutants (ozone, sulfur dioxide)

Cold dry air and strong odors

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

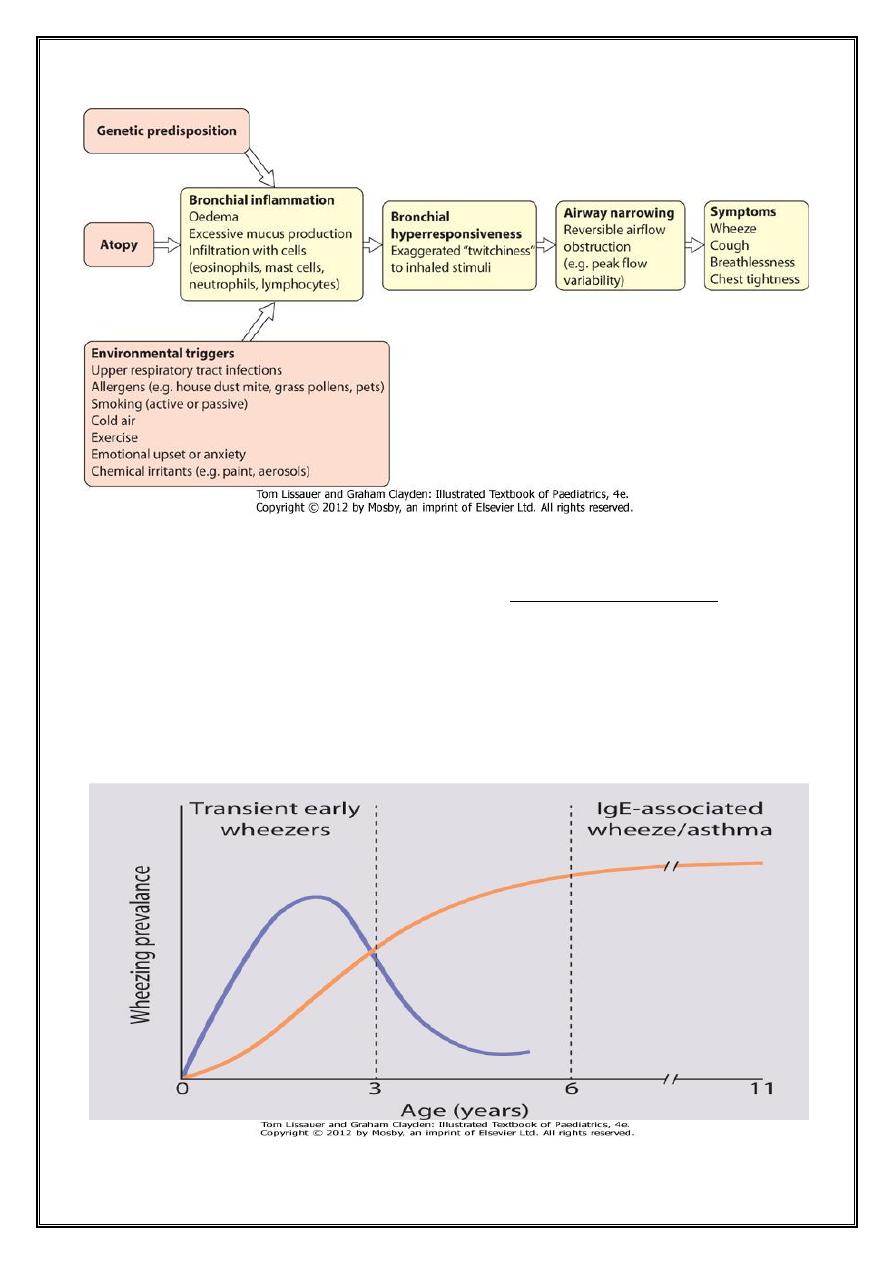

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, childhood asthma appears to be increasing in prevalence, despite

considerable improvements in management.

In 56 countries found a wide range in asthma prevalence, from 1.6 to 36.8%.

Approximately 80% of all asthmatics report disease onset prior to 6 yr of age.

Only a minority will go on to have persistent asthma in later childhood.

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Intermittent dry coughing and/or expiratory wheezing are the most common

chronic symptoms of asthma.

shortness of breath

worse at night

Daytime symptoms, often linked with physical activities

RISK FACTORS

history of other allergic conditions (allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis,

atopic dermatitis, food allergies)

Parental asthma, and/or symptoms apart from colds, supports the diagnosis of

asthma.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

Lung function tests can help to confirm the diagnosis of asthma and determine

disease severity.

Chest radiographs in children with asthma often appear to be normal,

hyperinflation (flattening of the diaphragms) and peribronchial thickening.

Asthma masqueraders (aspiration pneumonitis, bronchiolitis obliterans)

Asthma exacerbations (atelectasis, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax). CT

scans may be needed.

Other tests, such as allergy testing to assess sensitization to inhalant allergens,

help with the management and prognosis of asthma.

88% of asthmatic children had inhalant allergen sensitization by allergy prick

skin testing.

TREATMENT

Principles of Asthma Pharmacotherapy:

Treat all “persistent” asthma with anti-inflammatory controller medication

Daily controller therapy is not recommended for mild intermittent asthma.

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

The “three strikes” rule

Day time asthma symptoms at least 3 times per wk,

Awakens at night at least 3 times per mo,

Experiences asthma exacerbations that requires short courses of

systemic corticosteroids at least 3 times a yr.

Then that patient should receive daily controller therapy

(ICS) therapy is recommended as preferred therapy for all levels of asthma

severity except for the mild intermittent category.

Leukotriene pathway modifiers or sustained-release theophylline (only for

patients >5 yr of age) are alternatives for mild persistent asthmatics.

Combination of a low-to-medium dose ICS with a long-acting β-agonist or a

leukotriene modifier or theophylline is a mainstay therapy for moderate

persistent asthma in older children.

For infants and young children, medium-dose ICS alone it is considered a

preferred treatment for moderate persistent asthma.

Severe persistent asthmatics should receive high-dose ICS, a long-acting

bronchodilator, and routine oral corticosteroids if needed.

SABAs are the recommended quick-reliever medications for symptoms and

exercise pretreatment for all asthma severity levels

INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

Daily ICS therapy as the treatment of choice for all patients with persistent

asthma.

ICS reduce asthma symptoms, improve lung function, reduce “rescue”

medication use and, most important, reduce urgent care visits,

hospitalizations, and prednisone use for asthma exacerbations by about 50%

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

LONG-ACTING INHALED β-AGONIST

Although LABAs (salmeterol, formoterol) are considered to be daily

controller medications, not intended for use as “rescue” medication for acute

asthma symptoms or exacerbations,

nor as monotherapy for persistent asthma.

LEUKOTRIENE-MODIFYING AGENTS

leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA)

Montelukast > 1 yr.

Zafirlukast > 5 yr

Decrease need for rescue β-agonist use

NONSTEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS

Cromolyn and nedocromil are non-corticosteroid anti-inflammatory agents

that can inhibit allergen-induced asthmatic responses and reduce exercise-

induced bronchospasm.

THEOPHYLLINE

Although it is considered an alternative monotherapy controller agent for

older children and adults with mild persistent asthma,

It is no longer considered a first-line agent for small children in whom there

is significant variability in the absorption and metabolism of different

theophylline preparations, necessitating frequent dose monitoring (blood

levels) and adjustments.

SHORT-ACTING INHALED β-AGONISTS

SABAs (albuterol, levalbuterol, terbutaline, pirbuterol) are the first drugs of

choice for acute asthma symptoms (“rescue” medication) and for preventing

exercise-induced bronchospasm.

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

ANTICHOLINERGIC AGENTS

ipratropium bromide are much less potent than the β-agonists.

Inhaled ipratropium is primarily used in the treatment of acute severe

asthma.

When used in combination with albuterol, ipratropium can improve lung

function and reduce the rate of hospitalization in children who present to the

emergency department with acute asthma.

Home Management of Asthma Exacerbations

Immediate treatment with “rescue” SABA

Short course of oral corticosteroid therapy

Injectable forms of epinephrine

Portable oxygen at home.

Call for emergency support services.

ED Management of Asthma

Oxygen

Inhaled β-agonist

Systemic corticosteroids

Inhaled ipratropium

Intramuscular injection of epinephrine or other β-agonist

Close monitoring of clinical status, hydration, and oxygenation

Intubation and mechanical ventilation

Dr: Muhi Lec :3

PROGNOSIS

Recurrent coughing and wheezing occurs in 35% of pre–school-age children.

⅓ continue to have persistent asthma into later childhood.

⅔ improve on their own through the preteen years.

That entire wheeze is not asthma

&

Asthma does not always wheeze