1

DISEASES OF THE SMALL INTESTINE

Abdullah Alyouzbaki

Lecturer of Medicine/Mosul Medical College

Gastroenterologist and hepatologist

20/12/2015

Lec1

Disorders causing malabsorption:

Coeliac disease

is an inflammatory disorder of the small bowel

occurring in genetically susceptible individuals, which results from

intolerance to wheat gluten and similar proteins found in rye, barley

and, to a lesser extent, oats.

o

The condition occurs worldwide but is more common in northern

Europe.

o

The prevalence is approximately 1%,

o

50% of these people are asymptomatic.

o

‘silent’ coeliac disease ‘latent’ coeliac disease – genetically

susceptible people who may later develop clinical coeliac disease.

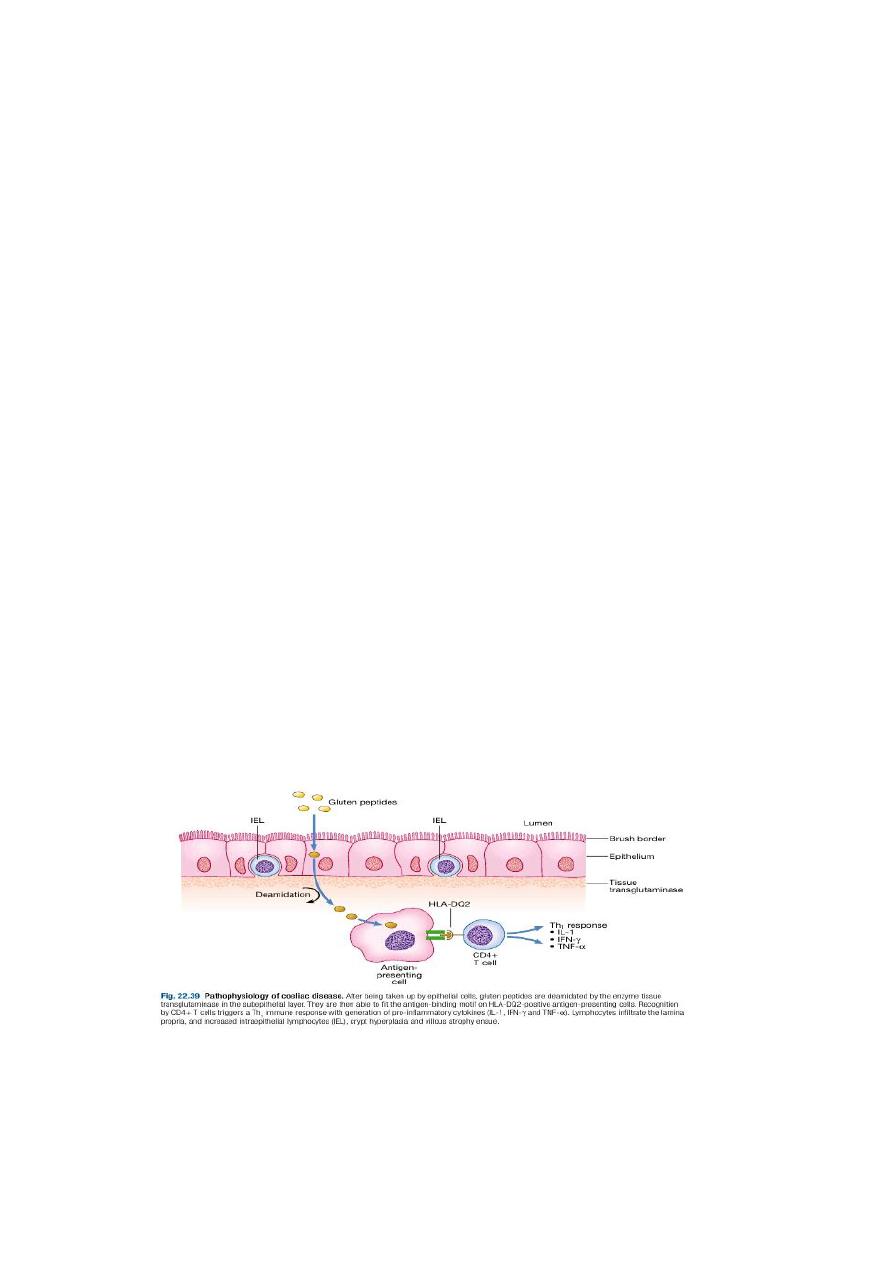

Pathophysiology

2

Presentation

Celiac disease can present at any age.

In infancy, it occurs after weaning on to cereals .

•

typically presents with diarrhea, malabsorption and failure to

thrive.

older children

o

:non-specific features such as delayed growth. Features of

malnutrition are found on examination and mild abdominal

distension.

o

pubertal delay

,

leading to short stature in adulthood.

In adults:

•

usually during the third or fourth decade

•

females > males.

•

The presentation is highly variable: florid malabsorption,

while others develop non-specific symptoms, such as

tiredness, weight loss, folate deficiency or iron deficiency

anaemia. oral ulceration, dyspepsia and bloating. mild

under-nutrition and osteoporosis.

3

Investigations

1)Duodenal biopsy: Endoscopic small bowel biopsy is the gold

standard. The histological features are usually characteristic but

other causes of villous atrophy should be considered.

4

2)Antibodies:

o

Anti tissue transglutamase antibodies and Anti-endomysial

antibodies of the IgA :They are sensitive (85–95%) and specific

(approximately 99%) for the diagnosis, except in very young

infants.

o

IgG antibodies, however, must be analysed in patients with coexisting

IgA deficiency.

o

they usually become negative with successful treatment.

3)Haematology and biochemistry:

•

A full blood count may show microcytic or macrocytic anaemia

from iron or folate deficiency and features of hyposplenism (target

cells, spherocytes and Howell– Jolly bodies).

•

Biochemical tests may reveal reduced concentrations of calcium,

magnesium, total protein, albumin or vitamin D.

5

Management

•

Exclusion of wheat, rye, barley and initially oats, although oats

may be re-introduced safely in most patients after 6–12 months.

•

Frequent dietary counselling.

•

Mineral and vitamin supplements.

•

Measurement of tTG or anti-endomysial antibodies.

Complications

•

Risk of malignancy, particularly of enteropathy-associated T-cell

lymphoma, small bowel carcinoma and squamous carcinoma of the

esophagus.

•

Ulcerative jejuno-ileitis.

•

Osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

Coeliac disease : still diarrhea in spite of gluten free diet??

•

Non Compliance , Non Compliance ,…..Non compliance.

•

Associations : pancreatic insufficiency , microscopic colitis,

inflammatory bowel disease.

•

Complications: ulcerative jejunitis , enteropathy associated T-cell

lymphoma, small bowel carcinoma and refractory coeliac disease.

6

Dermatitis herpetiformis

•

intensely itchy blisters over the elbows, knees, back and

buttocks.

•

Immunofluorescence shows granular or linear IgA deposition

at the dermoepidermal junction.

•

Almost all patients have partial villous atrophy on duodenal

biopsy, identical to that seen in coeliac disease, even though

they usually have no gastrointestinal symptoms.

•

The rash usually responds to a gluten free diet but some

patients require additional treatment with dapsone.

7

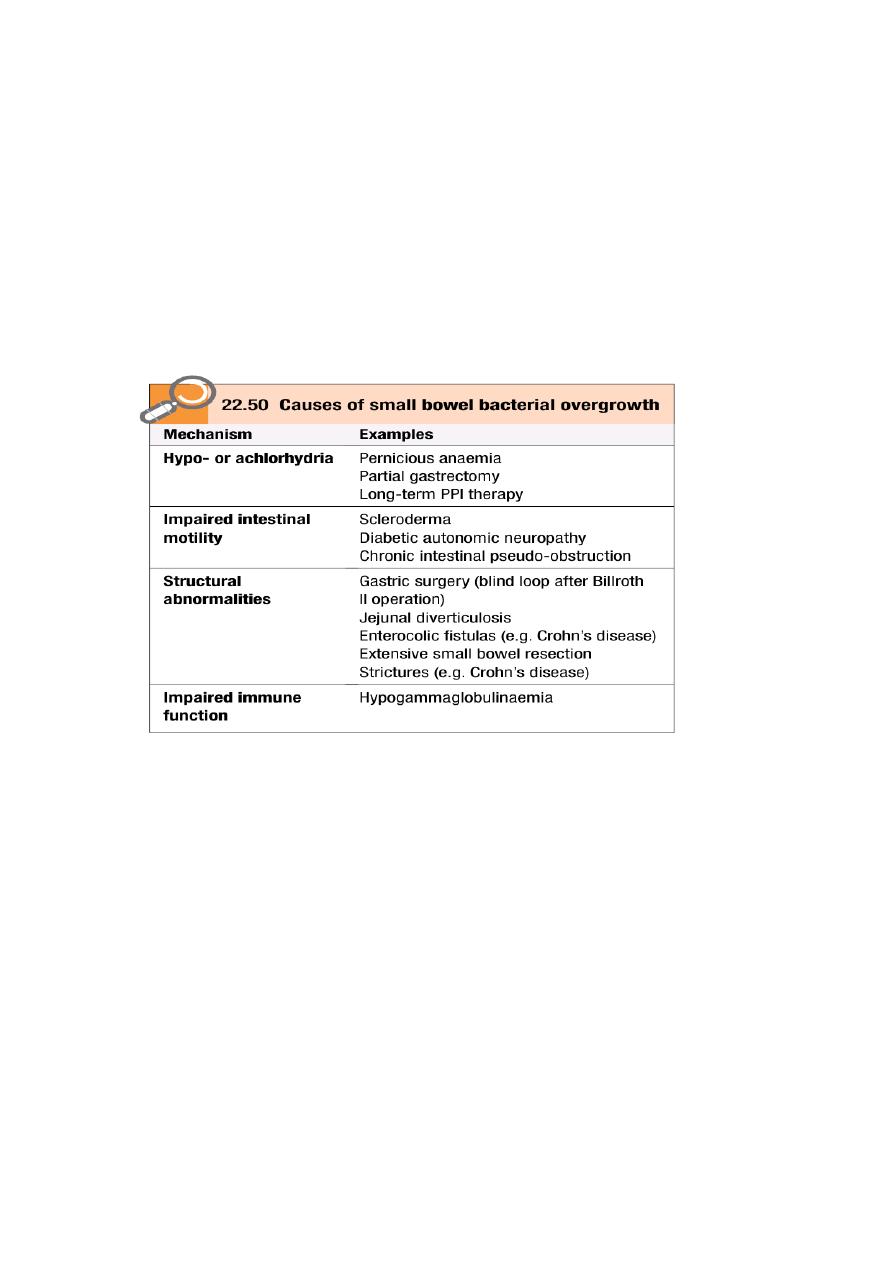

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth

(‘blind loop syndrome’)

•

The normal duodenum and jejunum contain fewer than

10⁴/mL. organisms, which are usually derived from saliva.

•

The count of coliform organisms never exceeds10⁴/mL .

•

In bacterial overgrowth, there may be 10

8

–10

10

/mL

organisms, most of which are normally found only in the colon.

Clinical features

The patient presents with watery diarrhoea and/or steatorrhoea, with

anaemia due to B12 deficiency. These arise because of deconjugation of

bile acids, which impairs micelle formation, and because of bacterial

utilisation of vitamin B12.

8

Investigations

•

Barium follow-through .

•

Jejunal contents for bacteriological examination can also be aspirated

at endoscopy (Gold standard) .

•

non-invasively using hydrogen breath tests.

•

Low serum levels of vitamin B12, with normal or elevated

folate levels because the bacteria produce folic acid.

Management

•

Treatment of the underlying cause of small bowel bacterial

overgrowth

•

Tetracycline (250 mg 4 times daily for 7 days) is then the

•

treatment of choice, Metronidazole (400 mg 3 times

daily) or ciprofloxacin (250 mg twice daily) is an alternative.

•

Some patients require up to 4 weeks of treatment and, in a few,

continuous rotating courses of antibiotics are necessary.

•

Intramuscular vitamin B12 supplementation.

9

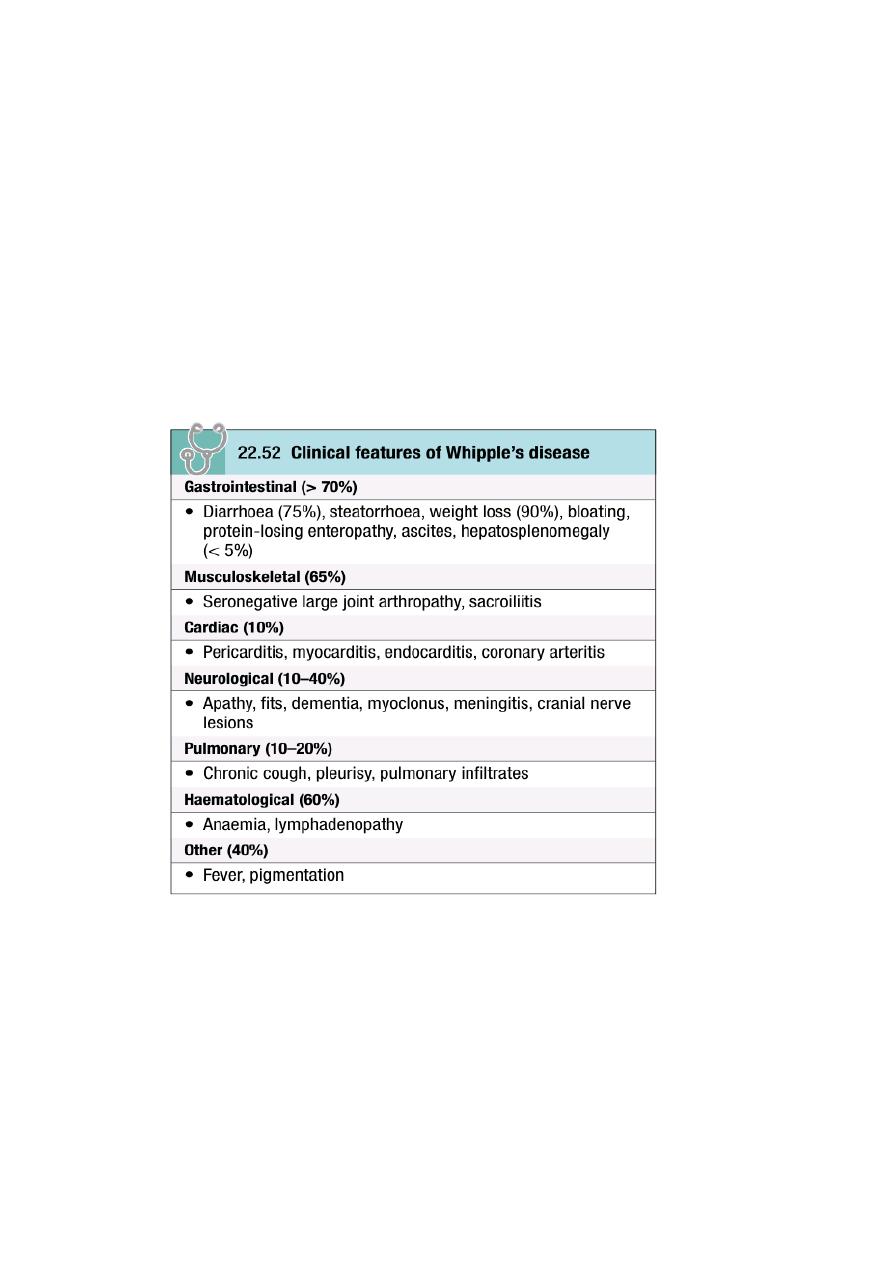

Whipple’s disease

•

This rare condition is characterised by infiltration of small intestinal

mucosa by ‘foamy’ macrophages, which stain positive with periodic

acid–Schiff (PAS) reagent.

•

Caused by infection with the Gram positive bacillus Tropheryma

whipplei.

•

The disease is a multisystem .

11

Diagnosis

:

•

characteristic features on small bowel biopsy, with characterisation of

the bacillus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Management:

•

often fatal if untreated .

•

Responds well, at least initially, to intravenous ceftriaxone

(2g daily for 2 weeks), followed by oral co-trimoxazole for

at least 1 year.

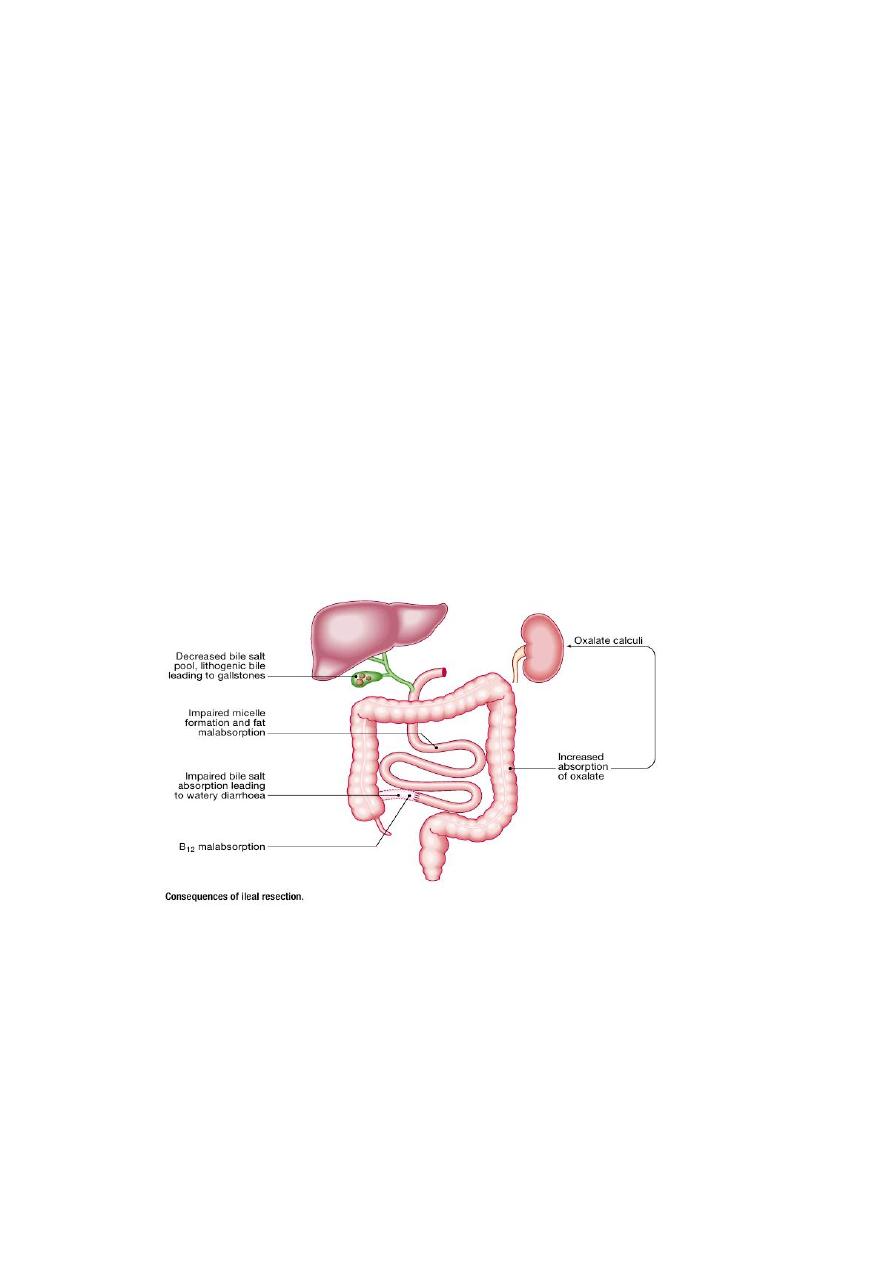

Ileal resection

•

The most common scenario is in patients with Crohn’s disease.

•

Diarrhea usually responds well to colestyramine, a resin which

binds bile salts in the intestinal lumen. Aluminium hydroxide can be

used as an alternative

.

11

Short bowel syndrome

•

Digestion and absorption are

normally completed within the

first 100 cm of jejunum, and

enteral feeding is usually still

possible if this amount of small

intestine remains.

•

The presence of some or all of

the colon can markedly

improve these losses by

increased water reabsorption.

•

The presence of an intact

ileocaecal valve ameliorates the clinical picture by slowing small

intestinal transit and reducing bacterialovergrowth.

Clinical features

•

Diarrhoea and steatorrhoea.

•

Dehydration and signs of hypovolaemia are common,

•

weight loss, loss of muscle bulk and malnutrition.

12

Management

•

In the immediate post-operative period: total parenteral nutrition

(TPN) should be started and PPI therapy given to reduce gastric

secretions.

•

Enteral feeding should be cautiously introduced after 1–2 weeks under

careful supervision and slowly increased as tolerated.

•

If less than 75 cm of small bowel remains, TPN is also needed.

•

Detailed nutritional assessments at regular intervals

•

Monitoring of fluid and electrolyte balance.

•

Adequate calorie and protein intake, Fats are a good energy source and

should be taken as tolerated. Medium-chain triglyceride are given

because they are more easily absorbed.

• Replacement of vitamin B12, calcium, vitamin D, magnesium, zinc and

folic acid.

•

Loperamide (2–4 mg 4 times daily) or codeine phosphate (30 mg 4–6

times daily) for diarrhoea.

•

Octreotide (50–200 μg 2–3 times daily by subcutaneous injection)

reduces gastrointestinal secretions.

•

some require long-term home TPN for survival .

•

Small bowel transplantation.

13

Radiation enteritis and proctocolitis

•

The risk varies with total dose, dosing schedule and the use of

concomitant chemotherapy.

•

Acute injury: nausea, vomiting , abdominal pain and diarrhea . When

the rectum and colon are involved, rectal mucus, bleeding and

tenesmus occur. rectal changes at sigmoidoscopy resemble ulcerative

proctitis or ulcerative colitis. Barium follow-through showing small

bowel strictures, ulcers and fistulae.

•

Chronic Phase

:Proctocolitis , Bleeding from telangiectasia, Small

bowel strictures, Fistulae: rectovaginal , colovesical , enterocolic ;

Adhesions, Malabsorption: bacterial overgrowth, bile salt

malabsorption(ileal damage).

Management

•

Diarrhoea : codeine phosphate, diphenoxylate or loperamide.

•

Local corticosteroid enemas can help proctitis.

•

Antibiotics may be required for bacterial overgrowth.

•

Nutritional supplements.

•

Colestyramine (4 g as a single sachet) is useful for bile salt

malabsorption.

•

Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation therapy may reduce bleeding

from proctitis.

•

Surgery should be avoided, if possible, because the injured intestine is

difficult to resect and anastomose, but may be necessary for

obstruction, perforation or fistula.

14

ISCHAEMIC GUT INJURY

•

Ischaemic gut injury is usually the result of arterial occlusion.

•

Severe hypotension and venous insufficiency are less frequent

causes.

•

The presentation is variable, depending on the different vessels

involved and the acuteness of the event.

•

Diagnosis is often difficult.

15

Acute small bowel ischaemia

•

An embolus from the heart or aorta to the superior mesenteric artery

is responsible for 40–50% of cases, thrombosis of underlying

atheromatous disease for approximately 25%, and non-o myocardial

infarction, heart failure, arrhythmias or sudden blood loss for

approximately 25%. Vasculitis and venous occlu cclusive ischaemia

due to hypotension complicating sion are rare causes.

•

The clinical spectrum ranges from transient alteration of bowel

function to transmural haemorrhagic necrosis and gangrene. Almost

all develop

•

abdominal pain that is more impressive than the physical findings.

•

In the early stages, the only physical signs may be a silent, distended

abdomen or diminished bowel sounds, peritonitis only developing

later.

•

Leucocytosis, metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphataemia and

hyperamylasaemia are typical.

•

Plain abdominal X-rays show ‘thumb-printing’ due to mucosal

oedema.

•

Mesenteric or CT angiography reveals an occluded or narrowed

major artery with spasm of arterial arcades, although most patients

undergo laparotomy on the basis of a clinical diagnosis without

angiography.

•

Resuscitation, management of cardiac disease and intravenous

antibiotic therapy, followed by laparotomy, are key steps.

•

If treatment is instituted early, embolectomy and vascular

reconstruction may salvage some small bowel.

•

In these rare cases, a ‘second look’ laparotomy should be undertaken

24 hours later and further necrotic bowel resected.

•

In patients at high surgical risk, thrombolysis may sometimes be

effective.

16

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

•

This results from atherosclerotic stenosis of the coeliac axis,

superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery. At least

two of the three vessels must be affected for symptoms to develop.

•

The typical presentation is with dull but severe mid- or upper

abdominal pain developing about 30 minutes after eating. Weight

loss is common because the patient is reluctant to eat, and some

experience diarrhoea.

•

Physical examination shows evidence of generalised arterial disease.

•

An abdominal bruit is sometimes audible but is non-specific.

•

The diagnosis is made by mesenteric angiography.

•

Treatment is by vascular reconstruction or percutaneous

angioplasty, if the patient’s clinical condition permits.

The condition is frequently complicated by intestinal infarction, if

left untreated.

17