Poisoning

Taking a history in poisoningWhat toxin(s) have been taken and how much?

What time were they taken and by what route?

Has alcohol or any drug of misuse been taken as well

?

Obtain details of the circumstances of the overdose from family, friends and ambulance personnel

Ask the general practitioner for background and details of prescribed medication

Assess suicide risk (full psychiatric evaluation when patient has physically recovered)

Capacity to make decisions about accepting or refusing treatment?Past medical history, drug history and allergies, social and family history?

Record all information carefully

Patients who are seriously poisoned must be identified early so that appropriate management is not delayed. Triage involves:

immediate measurement of vital signs

identifying the poison(s) involved and obtaining adequate information about them

identifying patients at risk of further attempts at self-harm and removing any remaining hazards from them.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is commonly employed to assess conscious level, although it has not been specifically validated in poisoned patients.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed and cardiac monitoring instituted in all patients with cardiovascular features or where exposure to potentially cardiotoxic substances is suspected.

Patients who may need antidotes should be weighed when this is feasible, so that appropriate doses can be prescribed.

Substances that are unlikely to be toxic in humans should be identified so that inappropriate admission and intervention are avoided

Substances of very low toxicity

Writing/educational materialsDecorating products

Cleaning/bathroom products (except dishwasher tablets which are corrosive)

Pharmaceuticals: oral contraceptives, most antibiotics (but not tetracyclines and antituberculous drugs), H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors, emollients and other skin creams, baby lotion

Miscellaneous: plasticine, silica gel, household plants, plant food

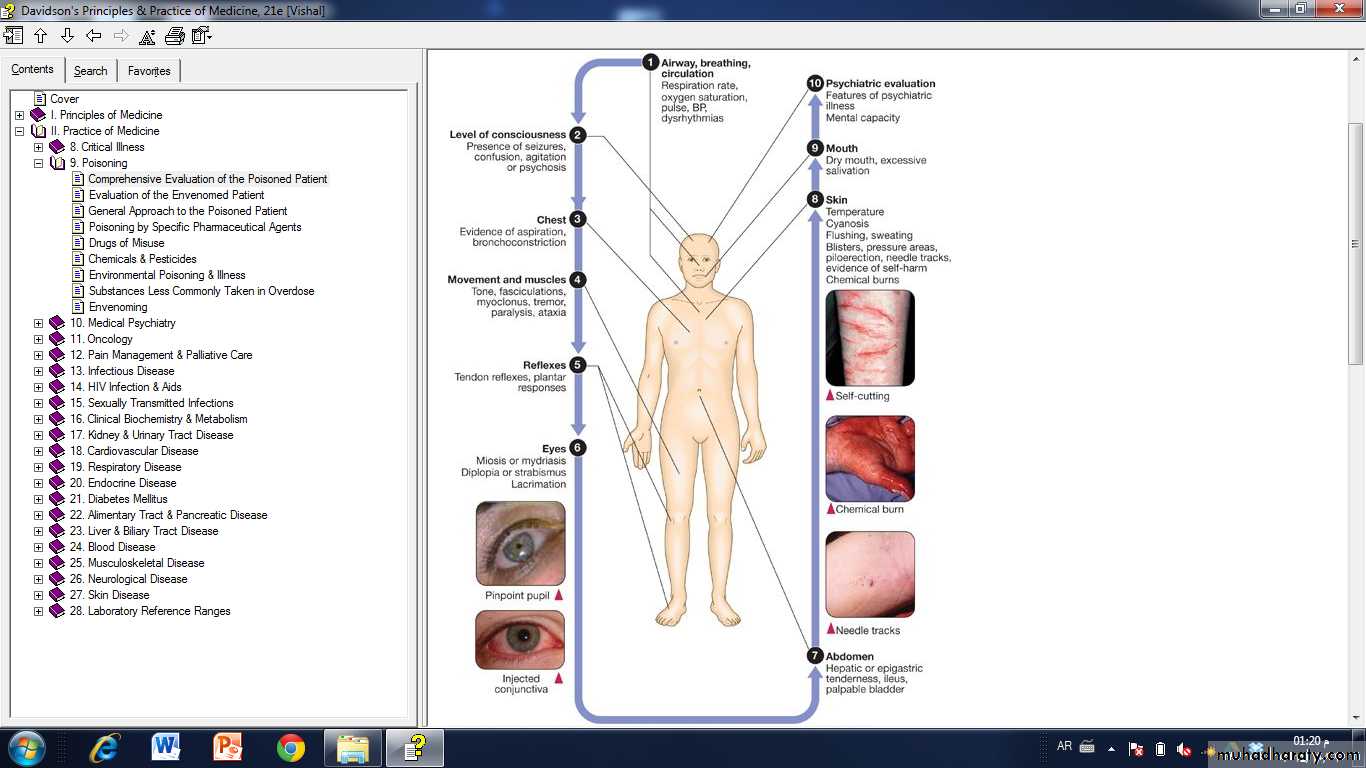

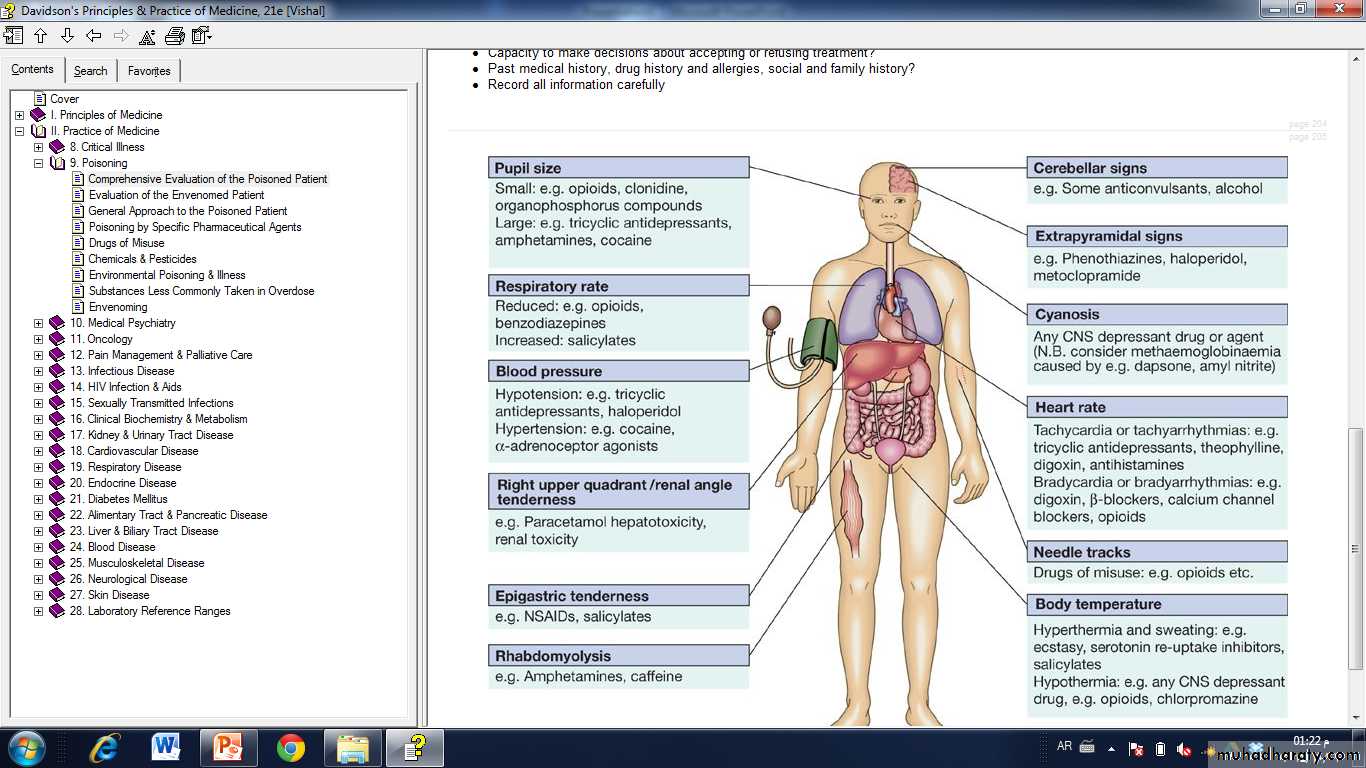

Clinical assessment and investigations

The patient may have a cluster of clinical features ('toxidrome') suggestive of poisoning with a particular drug typePoisoning is a common cause of coma, especially in younger people, but it is important to exclude other potential causes.

Serotonin syndrome

Anticholinergic

Stimulant

Sedative hypnotic

Opioid

Cholinergic muscarinic

Cholinergic nicotinic

Psychiatric assessment

Assess the risk of suicidal attempt

The use or abuse of certain psychotropic materials

Advice and treatment

General management

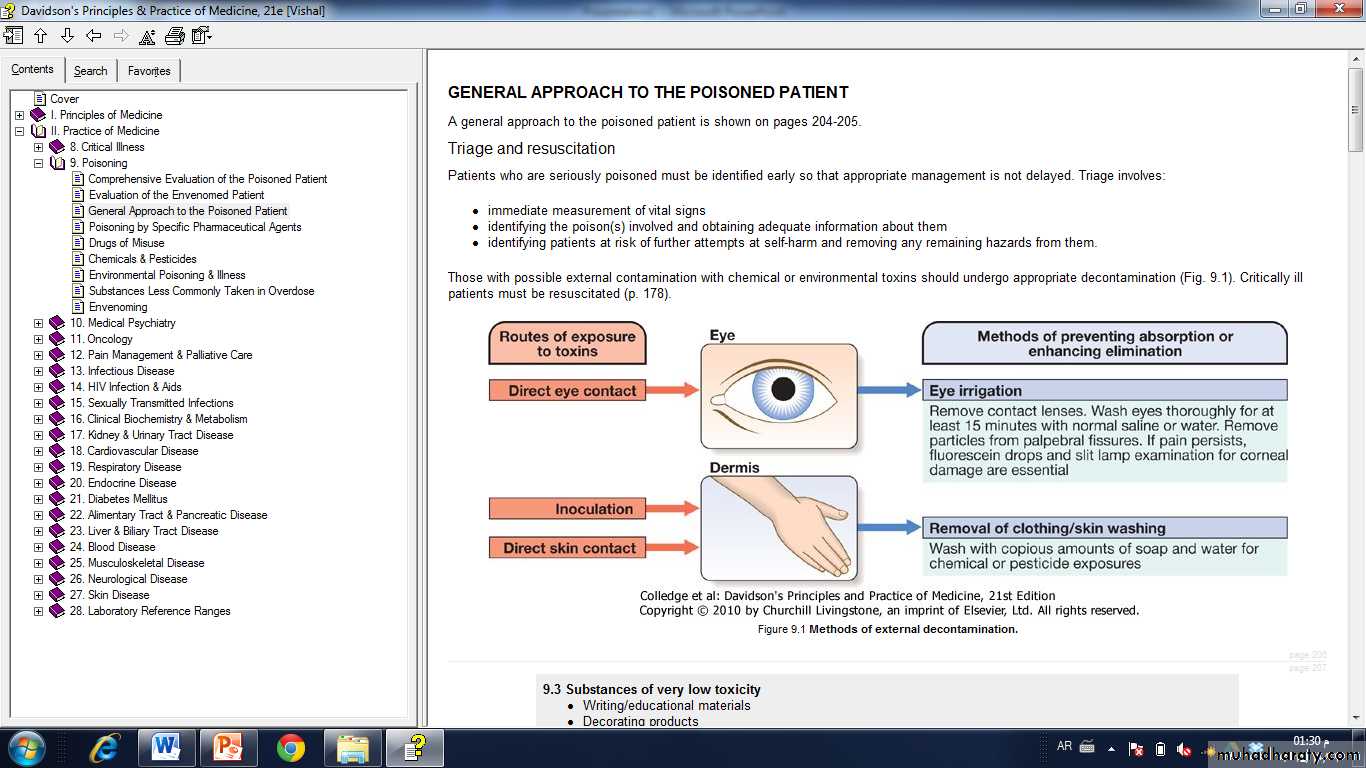

Patients presenting with eye or skin contamination should undergo appropriate local decontamination proceduresGastrointestinal decontamination

Patients who have ingested potentially life-threatening quantities of toxins may be considered for gastrointestinal decontamination if poisoning has been recent.

Induction of emesis using ipecacuanha is now never recommended.

Activated charcoal

Given orally as slurry, activated charcoal absorbs toxins in the bowel as a result of its large surface area. If given sufficiently early, it can prevent absorption of an important proportion of the ingested dose of toxin. However, efficacy decreases with time and current guidelines do not advocate use more than 1 hour after overdose in most circumstancesHowever, use after a longer interval may be reasonable when a delayed-release preparation has been taken or when gastric emptying may be delayed.

Some toxins do not bind to activated charcoal so it will not affect their absorption.

In patients with an impaired swallow or a reduced level of consciousness, the use of activated charcoal, even via a nasogastric tube, carries a risk of aspiration pneumonitis.

This risk can be reduced but not completely removed by protecting the airway with a cuffed endotracheal tube.

Substances poorly adsorbed by activated charcoal

MedicinesIron

Lithium

Chemicals

Acids*

Alkalis*

Ethanol

Ethylene glycol

Mercury

Methanol

Petroleum distillates*

* Gastric lavage contraindicated

Gastric aspiration and lavage

Gastric aspiration and/or lavage is now very infrequently indicated in acute poisoning, as it is no more effective than activated charcoal, and complications are common, especially aspiration. Use may be justified for life-threatening overdoses of some substances that are not absorbed by activated charcoal

Whole bowel irrigation

This is occasionally indicated to enhance the elimination of ingested packets or slow-release tablets that are not absorbed by activated charcoal (e.g. iron, lithium), but use is controversial. It is performed by administration of large quantities of polyethylene glycol and electrolyte solution (1-2 L/hr for an adult), often via a nasogastric tube, until the rectal effluent is clear.Contraindications include inadequate airway protection, haemodynamic instability, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, obstruction or ileus. Whole bowel irrigation does not cause osmotic changes but may precipitate nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain and electrolyte disturbances.

Urinary alkalinisation

Urinary excretion of weak acids and bases is affected by urinary pH, which changes the extent to which they are ionised.Highly ionised molecules pass poorly through lipid membranes and therefore little tubular reabsorption occurs and urinary excretion is increased.

If the urine is alkalinised (pH > 7.5) by the administration of sodium bicarbonate (e.g. 1.5 L of 1.26% sodium bicarbonate over 2 hrs), weak acids (e.g. salicylates, methotrexate and the herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and mecoprop) are highly ionised and so their urinary excretion is enhanced. This technique should be distinguished from forced alkaline diuresis, in which large volumes of fluid with diuretic are given in addition to alkalinisation.

This is no longer used because of the risk of fluid overload.

Urinary alkalinisation is currently recommended for patients with clinically significant salicylate poisoning when the criteria for haemodialysis are not met (see below). It is also sometimes used for poisoning with methotrexate. Complications include alkalaemia, hypokalaemia and occasionally alkalotic tetany (p. 444). Hypocalcaemia is rare.

Haemodialysis and haemoperfusion

These can enhance the elimination of poisons that have a small volume of distribution and a long half-life after overdose, and are useful when the episode of poisoning is sufficiently severe to justify invasive elimination methods.The toxin must be small enough to cross the dialysis membrane (haemodialysis) or must bind to activated charcoal (haemoperfusion)

Haemodialysis may also correct acid-base and metabolic disturbances associated with poisoning.

Haemodialysis and haemoperfusion

These can enhance the elimination of poisons that have a small volume of distribution and a long half-life after overdose, and are useful when the episode of poisoning is sufficiently severe to justify invasive elimination methods.The toxin must be small enough to cross the dialysis membrane (haemodialysis) or must bind to activated charcoal (haemoperfusion)

Haemodialysis may also correct acid-base and metabolic disturbances associated with poisoning.

Poisons effectively eliminated by haemodialysis or haemoperfusion

Haemodialysis

Ethylene glycol

Isopropanol

Methanol

Salicylates

Sodium valproate

Lithium

Haemoperfusion

TheophyllinePhenytoin

Carbamazepine

Phenobarbital

Amobarbital

Antidotes

Antidotes are available for some poisons and work by a variety of mechanisms: for example, by specific antagonism (e.g. isoproterenol for β-blockers), chelation (e.g. desferrioxamine for iron) or reduction (e.g. methylene blue for dapsone).The use of some antidotes is described in the management of specific poisons below.