د.منى

\

radiology L3

GIT IMAGING TECHNIQUE

Imaging techniques: general principles

Contrast examinations

1. Barium sulphate is the best contrast medium for demonstrating the GI tract on conventional

radiographic studies, e.g. fluoroscopy (screening). It produces excellent opacification, good

coating of the mucosa and is completely inert.

Its disadvantages are that the barium may solidify and impact proximal to a colonic or rectal stricture,

and it may cause a severe inflammatory peritonitis if there is a barium leak from the bowel. In

addition, patients must be reasonably mobile in order to undertake a complete barium study.

2. A water-soluble contrast medium, such as Gastrografin, is predominantly used when

perforations or anastomotic leaks are suspected (as it does not cause inflammatory

peritonitis), in cases where small bowel obstruction is suspected and in specific circumstances

in pediatric patients.

it is an irritant should it inadvertently enter the lungs; and it is less radio-opaque than barium.

Computed tomography

1. CT can show the full width of the wall of the structures in question as well as the surrounding

fat.

2. the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract may be evaluated using either Gastrografin as the

contrast agent (e.g. standard abdominal CT),

3. CT is therefore useful for diagnosing and staging GI tumours

4. assessing the complications of treatment such as surgery and chemotherapy.

5. CT can be used to diagnose appendicitis and is useful in patients with intestinal obstruction and

suspected damage to the bowel wall following trauma.

Ultrasound examinations

1. detect intra-abdominal fluid and assess the bowel wall in certain situations, but gives

limited information about the bowel mucosa.

2. diagnosis of infantile pyloric stenosis, intussusception and appendicitis when the diagnosis

is not obvious clinically.

3. The use of endoscopic ultrasound assessing the depth of invasion of tumours in the

oesophagus, gastric or rectal wall and diagnosing small tumours in the pancreas and wall of

the duodenum

.

Magnetic resonance imaging

1. be limited use, due to artefacts caused by peristalsis of the bowel.

2. assessing the local spread of rectal carcinoma prior to surgical resection,

3. assessing perianal fistula and abscess formation

4. The role in the assessment of oesophageal cancer is currently under development

د.منى

\

radiology L3

OESOPHAGUS

Imaging techniques

Plain films

1. do not show the oesophagus unless it is very dilated (e.g. achalasia),

2. but they are of use in demonstrating an opaque foreign body such as a bone lodgedin the

oesophagus

3. Plain films are also used to check the position of a nasogastric tube,

The barium swallow is the standard contrast examination employed to visualize the

oesophagus. The use of CT and endoscopic ultrasound is limited to the assessment of

oesophageal carcinoma.

Endoscopy :its primary investigation used in patient with dysplasia

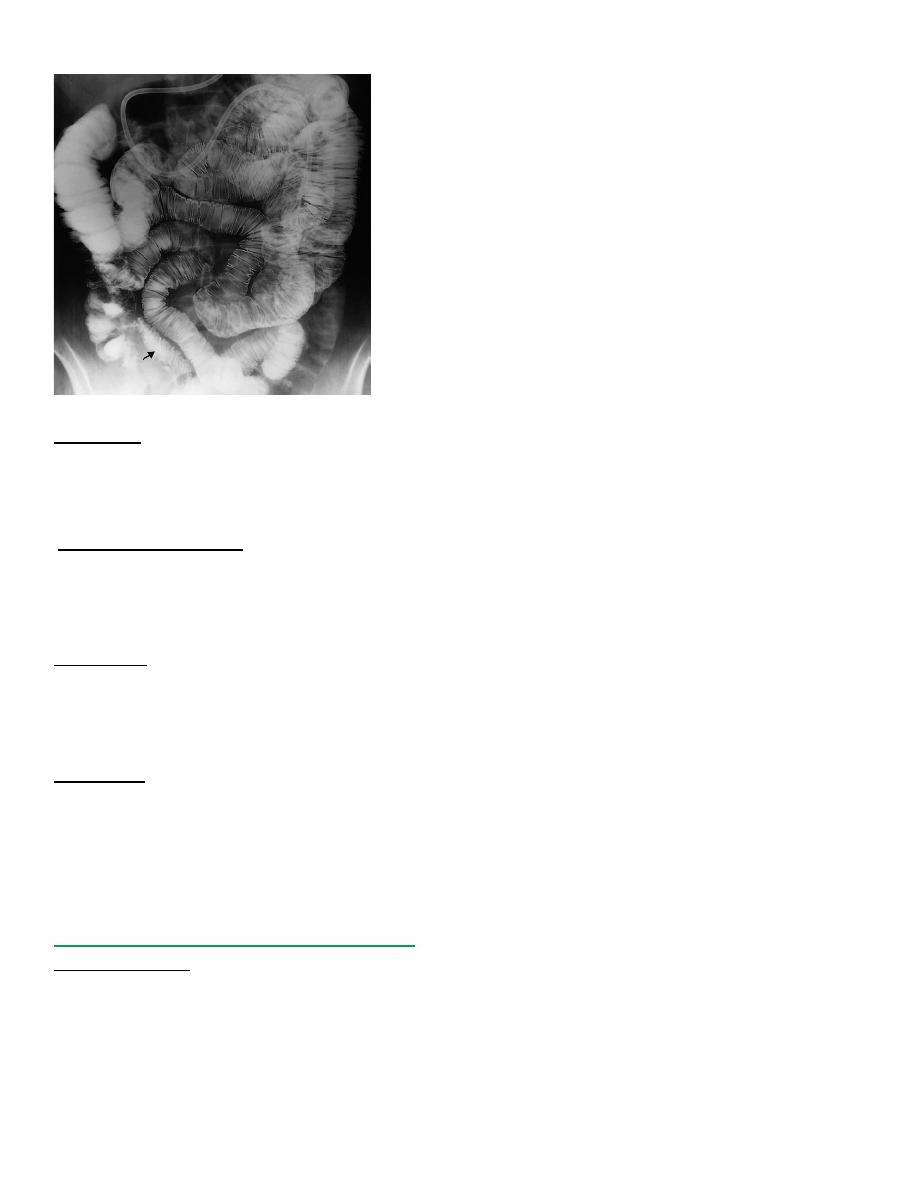

Barium swallow examination

The patient swallows a gas-producing agent to distend the oesophagus, followed by barium, and its

passage down the oesophagus is observed on a television monitor. Films are taken with the

oesophagus both full of barium to show the outline, and following the passage of the barium to show

the mucosal pattern. The oesophagus has a smooth outline when full of barium. When empty and

contracted, barium normally lies in between the folds of mucosa, which appear as three or four long,

straight, parallel lines. Peristaltic waves can be observed during fluoroscopy.

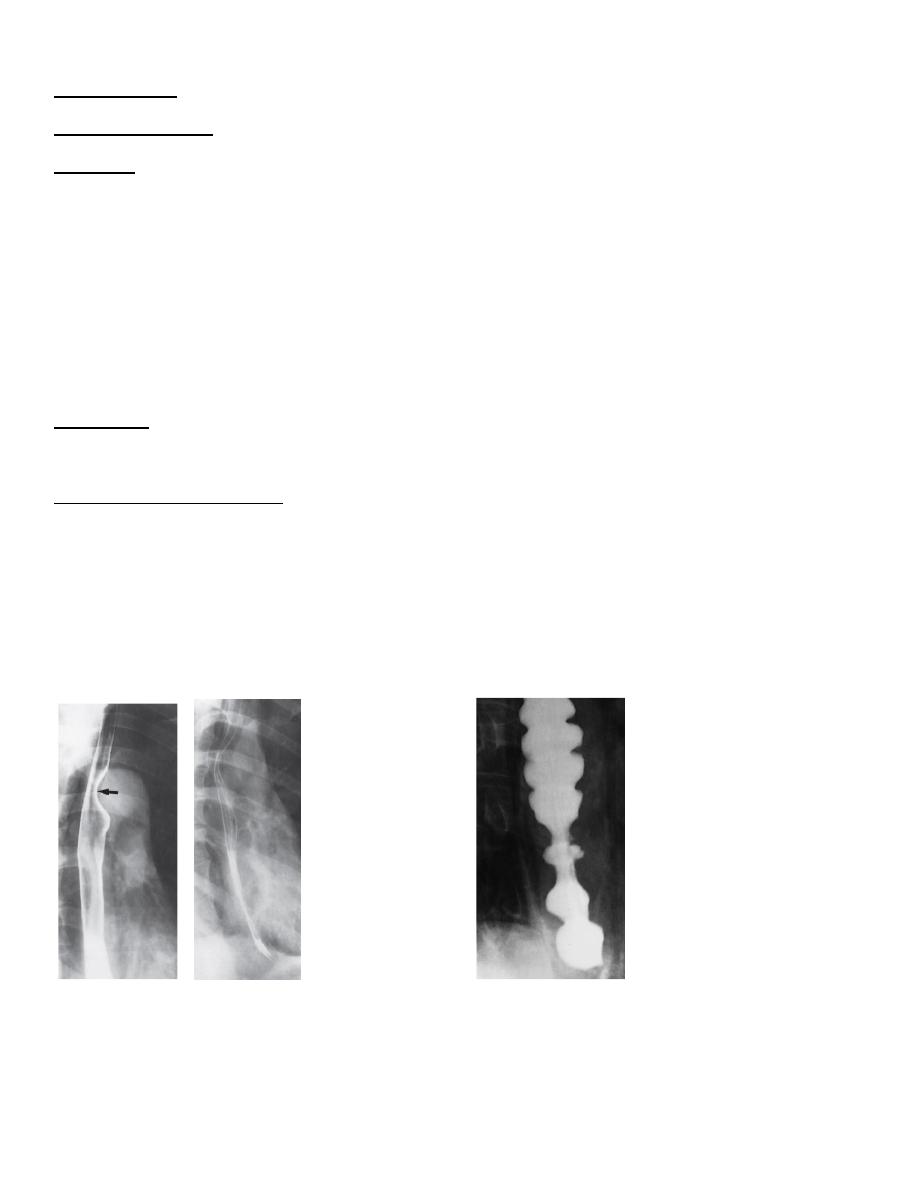

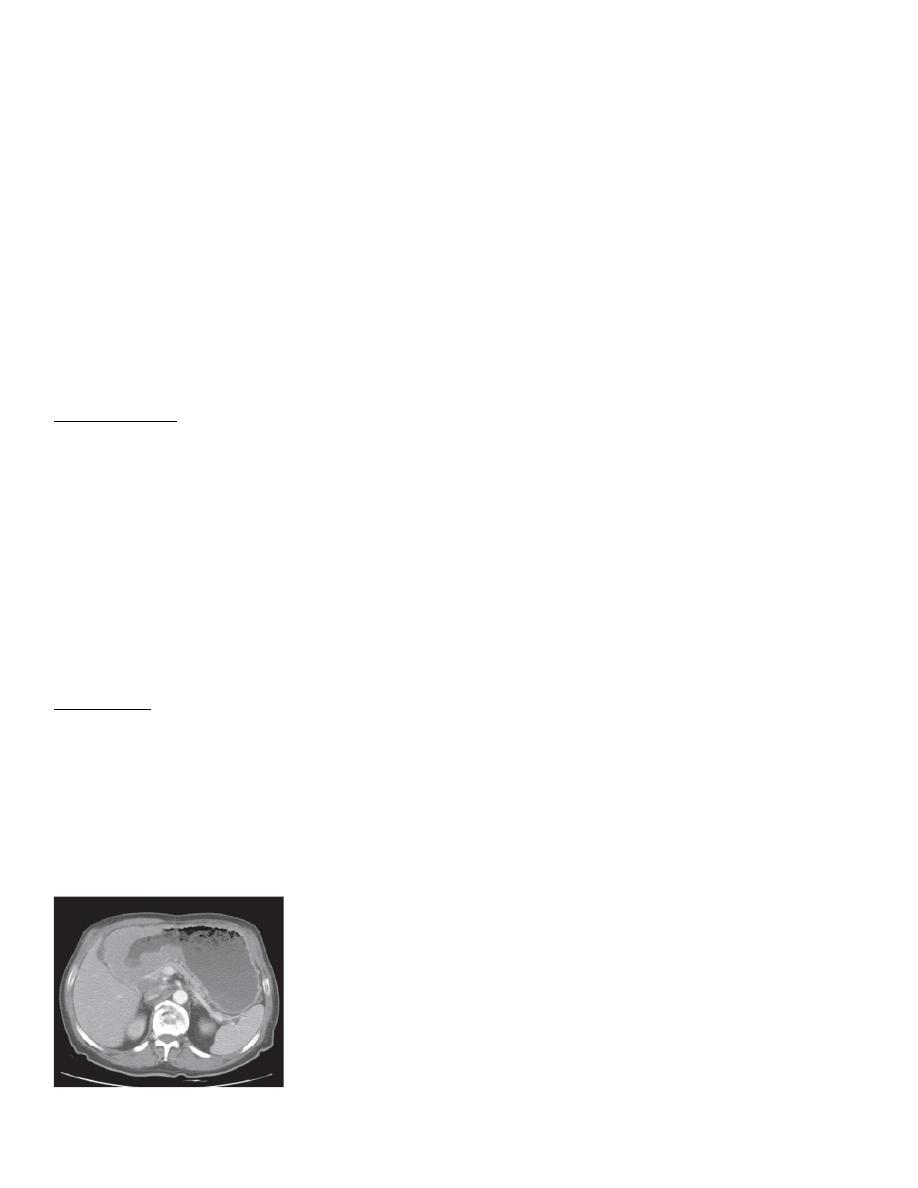

these are normal one

this tertiary contraction

It is important not to confuse a contraction wave with a true narrowing: a narrowing is constant

whereas a contraction wave is transitory. Sometimes the contraction waves do not occur in an orderly

fashion but are pronounced and prolonged, giving the oesophagus an undulated appearance . These

so called tertiary contractions usually occur in the elderly, and in most instances they do not give rise

to symptoms. Occasionally, tertiary contractions cause dysphagia.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Indications for contrast studies of the oesophagus

1. Swallowing disorders, including confirming or excluding a pharyngeal pouch

2. Determining the length of oesophageal strictures

3. Assessing possible mild gastro-oesophageal reflu. (although usually done by manometry)

4. Assessing the integrity of an oesophageal anastomosis

5. Following obesity reduction surgery and anti-reflux surgery

6. Demonstrating an oesophagobronchial or pleural fistula

Computed tomograpphy

Computed tomography is used in the staging of carcinoma of the oesophagus. The primary function of

CT is to detect distant disease (e.g. lung, liver or bone metastases), and although it does give

information on local staging, this is more accurately performed by endoscopic ultrasound

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography

In patients with oesophageal carcinoma who have potentially curable disease, an FDG-PET/CT study is

performed to identify any occult metastases prior to undertaking either surgery or definitive

chemoradiotherapy.

Oesophageal abnormalities

Strictures of the oesophagus

Causes of strictures of the oesophagus are :

1. Oesophageal cancer

2. Peptic strictures

3. Achalasia

4. Corrosive strictures

5. Benign tumours (leiomyomas)

6. Other mediastinal masses

7. Anomalous right subclavian artery

د.منى

\

radiology L3

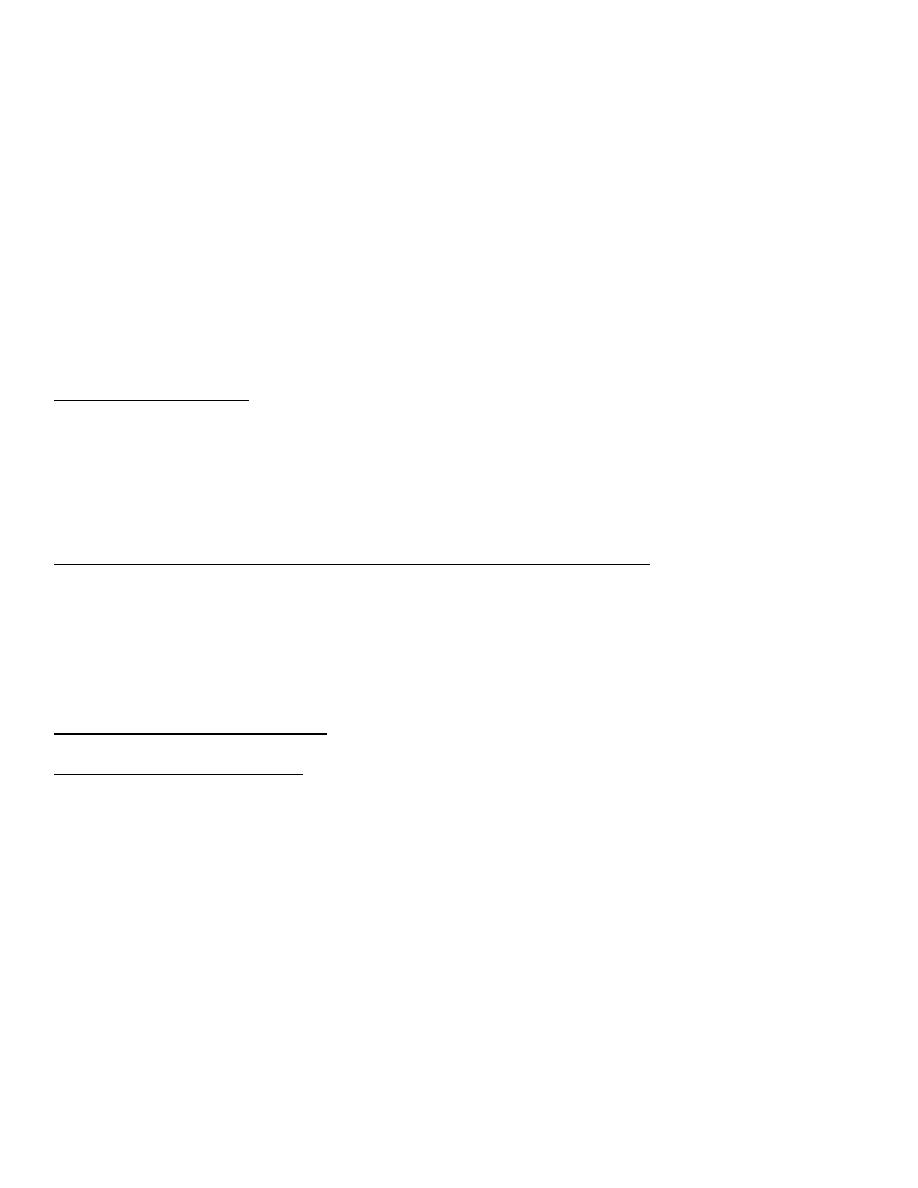

Oesophageal carcinoma

It may occur anywhere in the oesophagus, shows an irregular lumen with shouldered

edges and is often several centimetres in length

A soft tissue mass may be visible.

Assessing the extent of the tumour is carried out by endoscopic ultrasound and CT

examination. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is able to demonstrate the layers of the

oesophageal wall and the surrounding lymph nodes.

Oesophageal cancer is seen as a hypoechoic mass and the depth of invasion of the tumour into

the oesophageal wall may be assessed .EUS is also used to assess and, if necessary, biopsy,

regional lymph nodes to detect potential metastatic disease that might place the patient in a

palliative rather than curative pathway.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

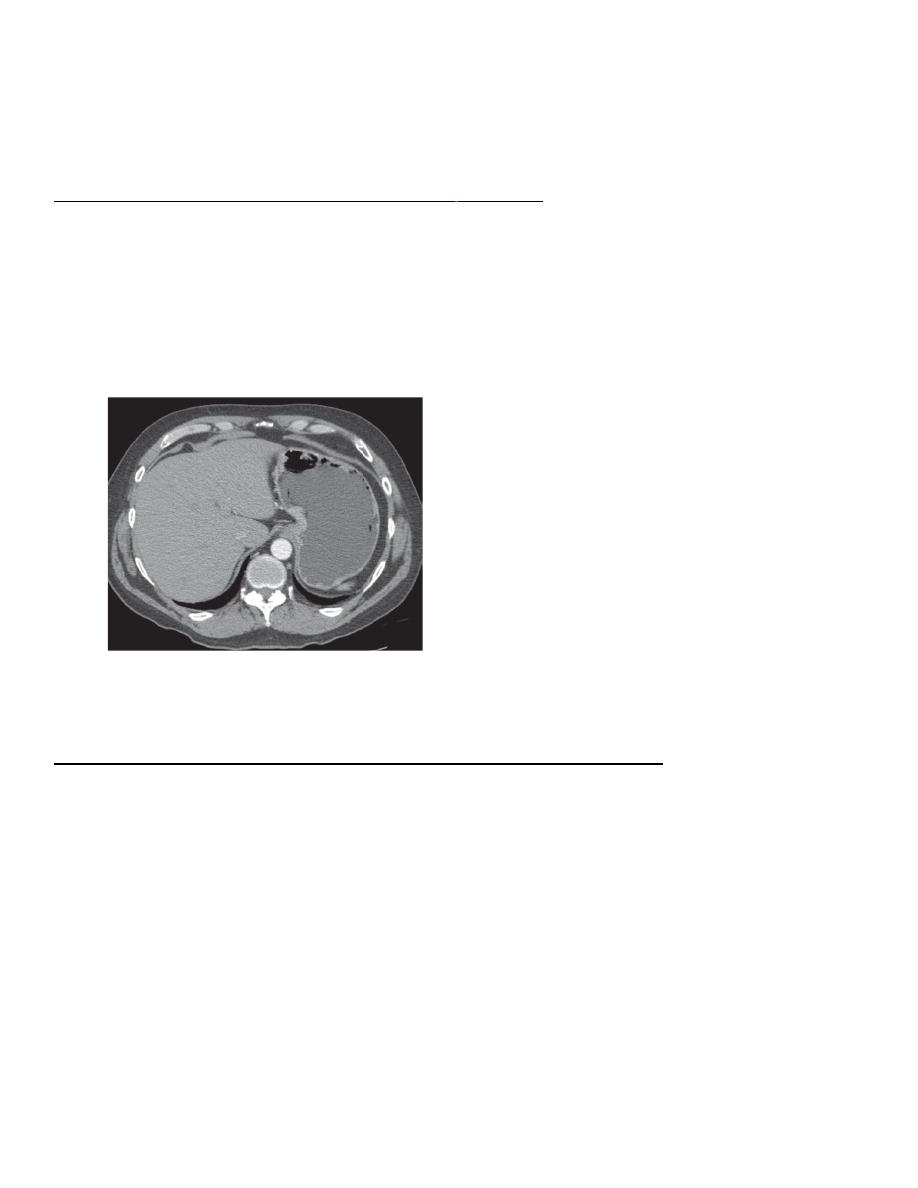

On CT the tumour is seen as a thickening of the oesophageal wall and the length of the tumour

can usually be assessed. CT may also show invasion of the mediastinum or adjacent structures,

evidence of metastatic spread to lymph nodes, liver or lungs .

FDG-PET/CT is used to exclude the presence of occult metastatic disease in patients who are

considered potentially curable (either by surgery or radical chemoradiotherapy) after initial

evaluation with CT and EUS . Assessment of response to treatment and follow-up of patients

with carcinoma of the oesophagus is usually done with CT and endoscopy.increasingly being

used to assess the response of the tumour to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, allowing an early

change in therapy in patients who are non-responders.

Peptic strictures

Peptic strictures can be demonstrated at barium swallow.

They are found at the lower end of the oesophagus and are almost invariably associated with a

hiatus hernia and gastro-oesophageal reflux and, therefore, the stricture may be some distance

above the diaphragm.

Peptic strictures are characteristically short and have smooth outlines with tapering ends

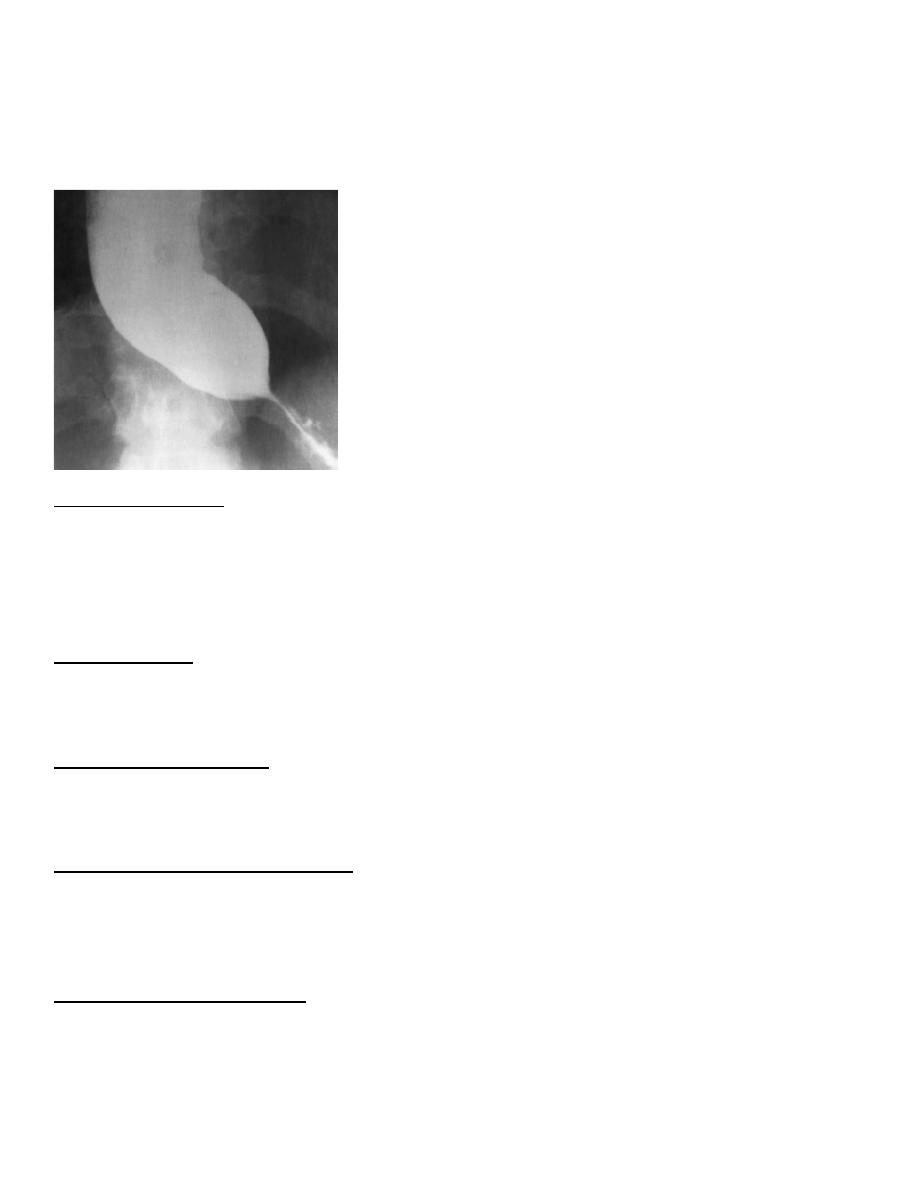

Achalasia

Achalasia is a neuromuscular abnormality resulting in failure of relaxation at the cardiac

sphincter, which presents at barium swallow examination as a smooth, tapered narrowing,

always at the lower end of the oesophagus .

There is associated dilatation of the oesophagus, which often shows absent peristalsis. The

dilated oesophagus usually contains food residue and may be visible on the plain chest

radiograph.

The lungs may show consolidation and bronchiectasis from aspiration of the oesophageal

د.منى

\

radiology L3

contents.

The stomach gas bubble is usually absent because the oesophageal contents act as a water

seal, but this sign is not diagnostic of achalasia as it is seen in other causes of oesophageal

obstruction and can occasionally be observed in healthy people.

Corrosive strictures

Corrosive strictures are the result of swallowing corrosives such as acids or alkalis. They are

long strictures that begin at the level of the aortic arch.

As with other benign strictures, they are usually smooth with tapered ends on barium swallow

examinations, but may be irregular

Benign tumours

Leiomyomas cause a smooth, rounded indentation into the lumen of the oesophagus.

A soft tissue mass may be seen in the mediastinum indicating extraluminal extension.

Other medistinal masses

Mediastinal masses (e.g. lymphadenopathy secondary to lymphoma or lung cancer) can cause

extrinsic compression and narrowing of the oesophagus.

Anomalous right subclavian artery

An anomalous right subclavian artery, which, instead of coming from the innominate artery,

arises as the last major branch from the aortic arch, gives rise to a characteristic short, smooth

narrowing as it crosses behind the upper oesophagus .

Dilatation of the oesophagus

There are two main types of oesophageal dilatation –

obstructive and non-obstructive:

د.منى

\

radiology L3

• Dilatation due to obstruction is associated with a visible stricture. The patient with a carcinoma

usually presents with dysphagia before the oesophagus becomes very dilated. On the other hand,

a markedly dilated oesophagus indicates a very longstanding condition, usually achalasia or

occasionally a benign stricture.

• Dilatation without obstruction occurs in scleroderma. The disease involves the oesophageal

muscle, resulting in dilatation of the oesophagus, which resembles an inert tube with no peristaltic

movement so that barium does not flow from the oesophagus into the stomach unless the patient

stands upright.

Other abnormalities of the oesophagus

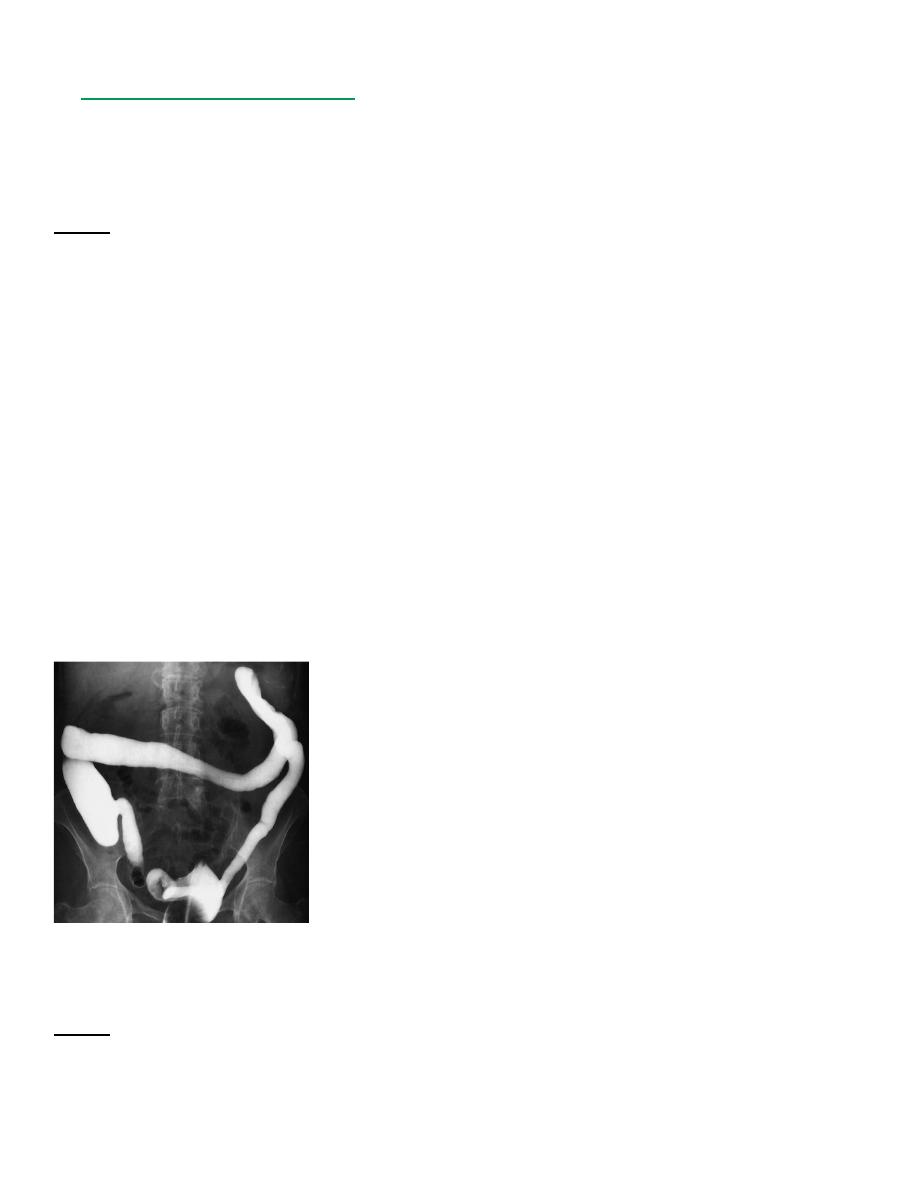

1. An oesophageal web is a thin, shelf-like projection arising from the anterior wall of the cervical

portion of the oesophagus and can only be seen when the oesophagus is full of barium . A web

may be an isolated finding, but the combination of a web, dysphagia and iron deficiency

anaemia is known as Plummer–Vinson syndrome.

2. Oesophageal diverticula are saccular outpouchings, which are often seen as chance findings, in

the intrathoracic portion of the oesophagus. One type of diverticulum, the pharyngeal pouch

or Zenker’s diverticulum is important as it may give rise to symptoms caused by retention of

food and pressure upon the oesophagus. A pharyngeal pouch arises through a congenital

weakness in the inferior constrictor muscle of the pharynx and comes to lie behind the

oesophagus near the midline. It may reach a very large size and can cause displacement and

compression of the oesophagus.

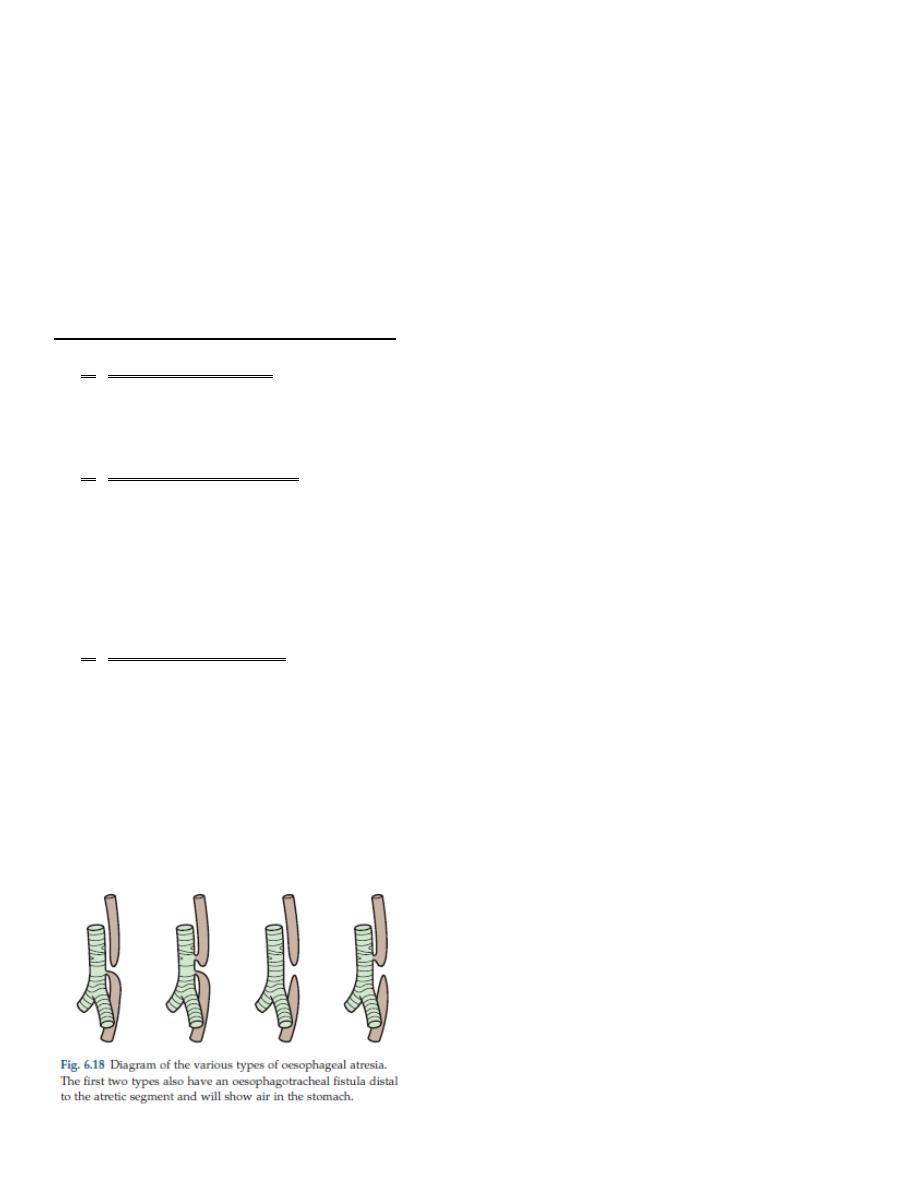

3. In oesophageal atresia, the oesophagus ends as a blind pouch in the upper mediastinum.

Several different types exist , but the most frequent is for the upper part of the oesophagus to

be a blind sac with a fistula between the lower segment of the oesophagus and the

tracheobronchial tree. A plain abdominal film will show air in the bowel if a fistula is present

between the tracheobronchial tree and the oesophagus distal to the atretic segment. The

diagnosis of oesophageal atresia is made by passing a soft tube into the oesophagus and

showing that the tube holds up or coils in the blind-ending pouch. The use of contrast agents is

potentially dangerous because the contrast may cause respiratory problems if it spills over into

the trachea.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

STOMACH AND DUODENUM

Imaging techniques

Barium meal examination

Barium meal examination is now rarely performed as it has been superseded by endoscopy.

The stomach is distended with a gas-producing agent, and an intravenous injection of a short-

acting smooth muscle relaxant is often given. The patient drinks about 200 mL of barium. Films

are taken in various positions with the patient both erect and lying flat, so that each part of the

stomach and duodenum is shown distended by barium and also distended with air but coated

with barium to show the mucosal pattern

The duodenal cap or bulb arises just beyond the short pyloric canal, and the duodenum forms a

loop around the head of the pancreas to reach the duodenojejunal flexure.

Diverticula arising beyond the first part of duodenum are a common finding and are usually

without clinical significance

have an important role in functional studies of the upper GI tract or to evaluate any potential

anastomotic leak For this reason it is usually water-soluble contrast agents that are used, which

are more rapidly resorbed than barium and importantly will allow timely subsequent imaging

with CT.

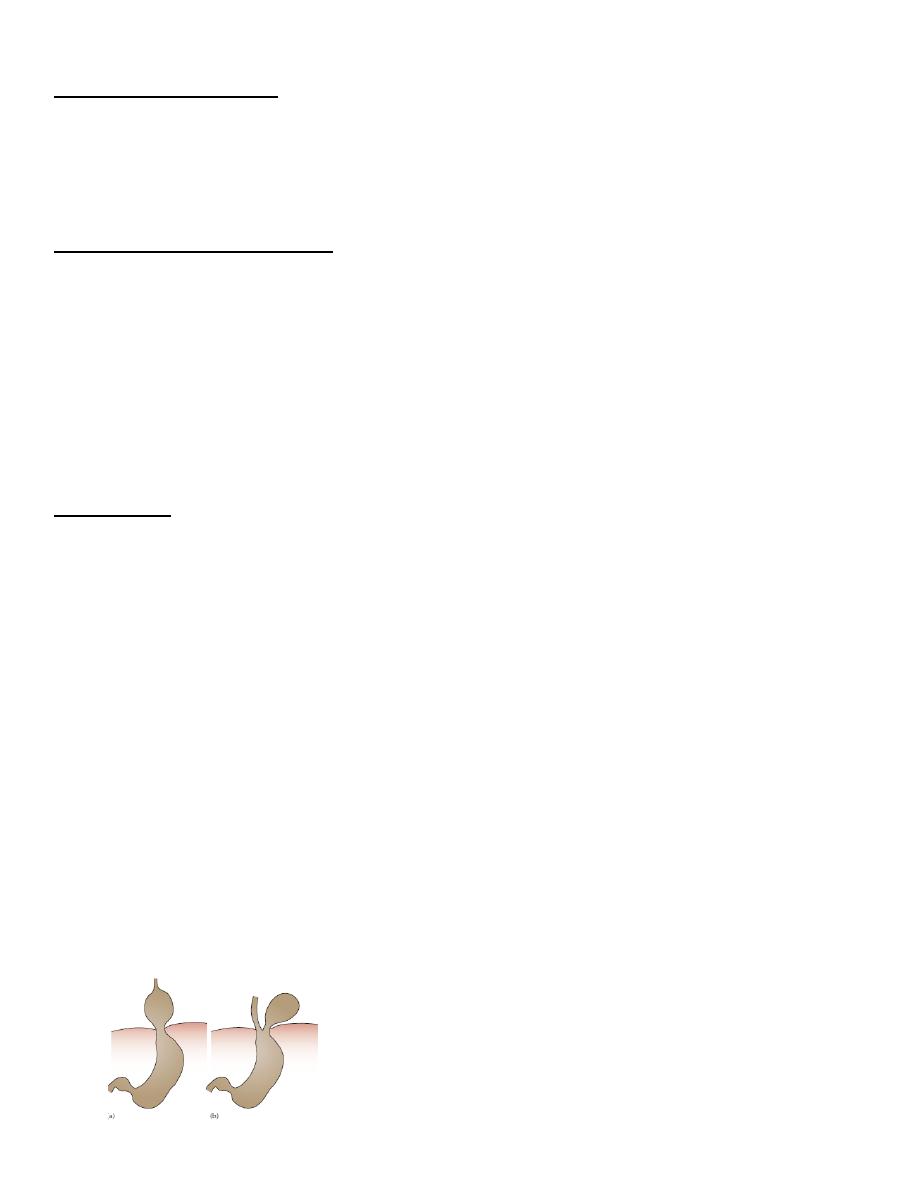

Computed tomography

Firstly, the patient must not eat for 6 hours prior to the CT to ensure that no food residues

remain in the stomach, which could obscure or mimic disease.

The patient is usually given about 100 mL of tap water to drink (acting as a negative contrast)

as well as a smooth muscle relaxant, in order to distend the stomach and duodenum. If the

stomach is not distended during the scan, any thickening of the gastric wall could be

misinterpreted as being a mass. During the scan, intravenous iodinated contrast medium is

injected to demonstrate enhancement of both the normal structures as well as to distinguish

the enhancement characteristics of any abnormality.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Upper GI endoscopy is widely used as the initial investigation in patients with possible disease

of the stomach and duodenum.

It enables the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum to be directly inspected and biopsied.

Indications for contrast studies of the stomach and

duodenum

1. Failed gastroscopy

2. Assessment of duodenal strictures that cannot be characterized or navigated on endoscopy

3. Assessment of functional patency/gastric emptying following gastroenterostomy or anti-

obesity surgery

4. To confirm or rule out anastomotic leak following gastric surgery (a water-soluble contrast

agent)

5. Staging tumors discovered by endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy is widely used as the initial investigation in patients with possible disease

of the stomach and duodenum.

It enables the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum to be directly inspected and biopsied.

Indications for upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopyDiagnosis and follow-up

1. Peptic ulcer disease

2. Haematemesis and melaena

3. Dyspepsia and dysphagia

4. Barrett’s oesophagus

5. Biopsies

6. Coeliac disease

7. Confirmation and follow-up of malignant tumours

8. Therapeutic

9. Injection/clipping/banding to stop bleeding from ulcers or

10. oesophageal varices

11. Removal of ingested foreign bodies

12. Stenting of upper GI strictures

13. Feeding tube placement

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Specific diseases of the stomach and duodenum

Peptic ulcer

Gastric ulcers may be benign or malignant so confirmation at gastroscopy is routinely

undertaken, whereas duodenal ulcers are almost invariably benign.

Ulcers are identified as projections of barium beyond the mucosal profile. With duodenal

ulceration, the duodenal cap (bulb) may be very deformed by scarring

Gastric carcinoma

However, gastroscopy has now almost completely taken over the diagnosis of Ca.

At barium examination, gastric carcinoma typically produces an irregular filling defect with

alteration of the normal mucosal pattern

Computed tomography is the main imaging modality for the preoperative staging of patients

with gastric cancer as it can show the extent of the primary tumour but also any distant disease

EUS may be used in some cases for local staging and patients will undergo staging laparoscopy

prior to curative surgery.

FDG-PET/CT does not have a clear role in the primary staging of gastric cancer due to the

normal uptake of FDG by the gastric mucosa.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs)

arise from the wall of the stomach resulting in a smooth, round, submucosal filling defect,

which may ulcerate as the tumour enlarges

GISTs are a group of tumours that are usually benign and well differentiated; they may occur

anywhere in the GI tract but 60–70% occur in the stomach.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

A leiomyoma is a submucosal tumour which, as well as projecting into the lumen of the

stomach, may have a large extraluminal extension that can be easily recognized at CT.

Neuroendocrine tumours of the stomach and duodenum include gastric carcinoid tumours and

gastrinomas.

Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumours can be found anywhere in the GI tract, particularly the

appendix, but can be found incidentally in the stomach often as multiple small (<1 cm)tumours

on a background of pernicious anaemia/chronic atrophic gastritis. Occasionally they are seen in

association with MEN (multiple endocrine neoplasia) type 1 in association with other endocrine

tumours, or as a solitary larger tumour (>3 cm) where they can cause local symptoms of

abdominal pain and bleeding as well as the carcinoid syndrome.

Gastrinomas usually secrete gastrin, resulting in increased gastric acidity and peptic ulceration.

Gastrinomas are often very small and typically enhance brightly in the arterial phase

Gastric polyps

Gastric polyps may be single or multiple.

They may be sessile or have a stalk.

Even with high quality radiographs it is often impossible to distinguish benign from malignant

polyps.

For this reason, gastroscopy with biopsy or operative removal is invariably carried out on all

suspected polyps.

Other intraluminal defects within the stomach include food or blood following a

haematemesis. Sometimes ingested fibrous material, such as hair, may intertwine forming a

ball or bezoar

Lymphoma

The stomach is the most frequent site of lymphoma involving the GI tract, either as primary

disease or by infiltration from adjacent nodes.

The appearance of primary gastric lymphoma is typically of an extensive area of diffuse

thickening of the gastric wall

There may be extensive, bulky lymphadenopathy adjacent to the tumour.

The appearance may mimic gastric carcinoma.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Gastric outlet obstruction

In infants, pyloric stenosis is by far the commonest cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Often,

the diagnosis is made clinically and can be confirmed with ultrasound, which has superseded

barium meal.

Ultrasound shows a thickened, elongated pyloric canal

Causes of gastric outlet obstruction

Chronic duodenal ulceration: the diagnosis depends on demonstrating a very deformed,

stenosed duodenal cap. It

may or may not be possible to identify an actual ulcer crater

Carcinoma of the antrum

Duodenal, ampullary and pancreatic carcinoma

Acute or chronic pancreatitis, including pseudo cyst formation

Poor functional patency of a gastroenterostomy

Pyloric stenosis in infants

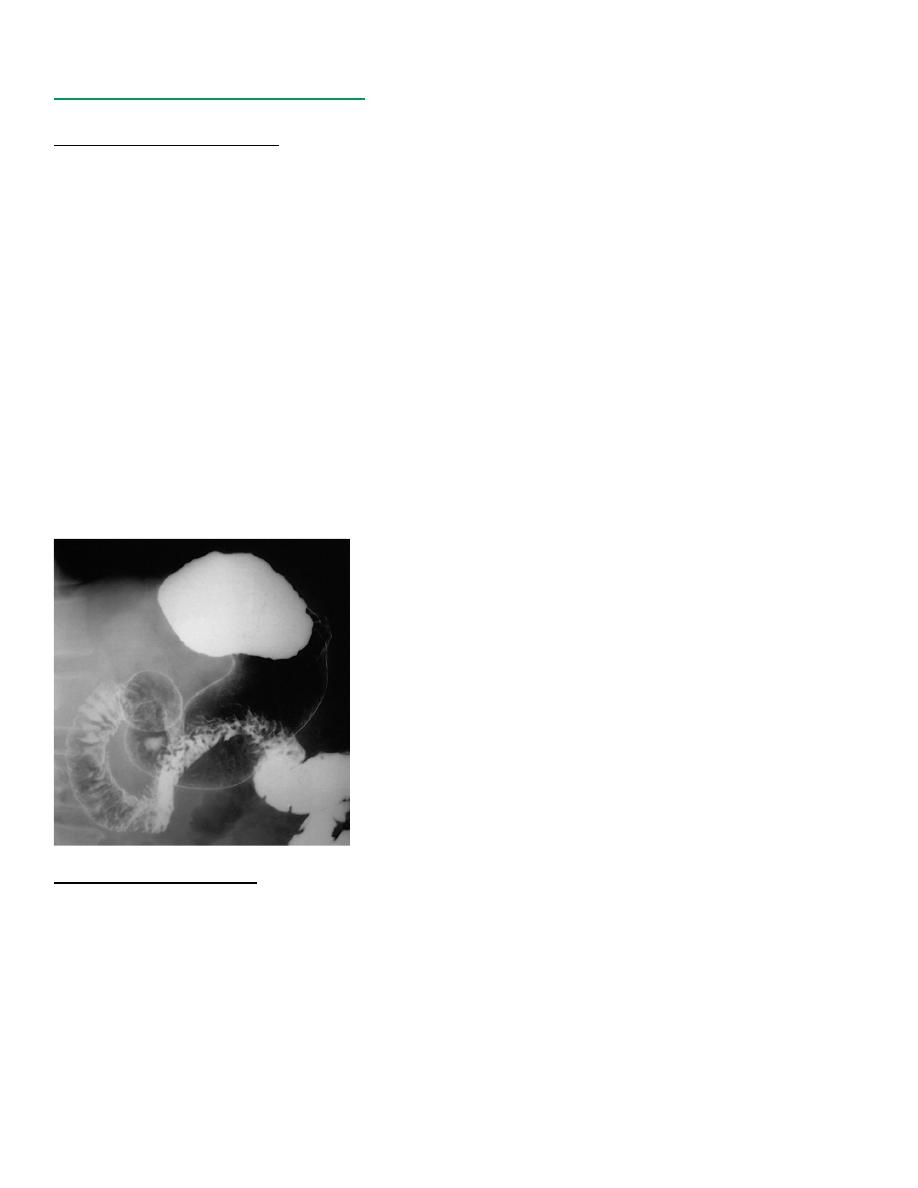

Hiatus hernia

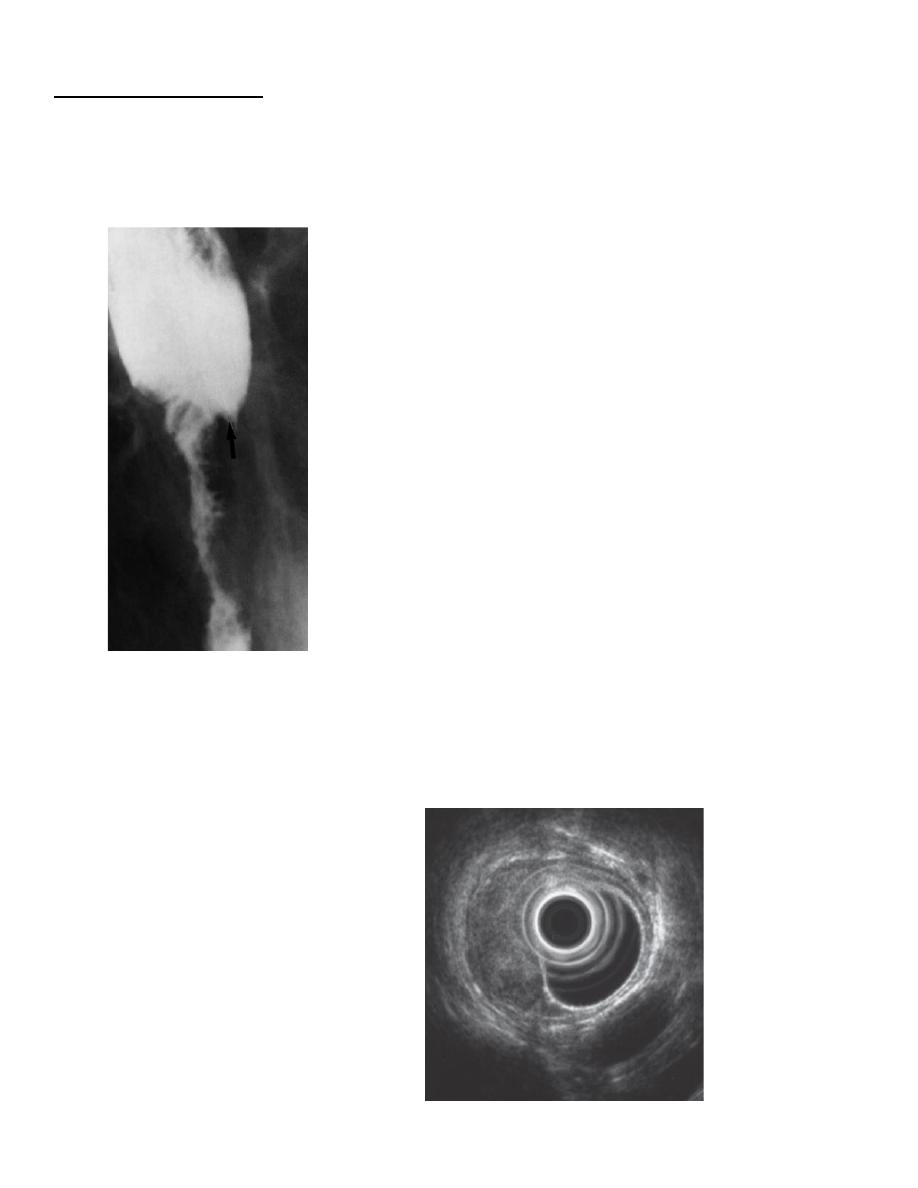

A hiatus hernia is a herniation of the stomach into the mediastinum through the oesophageal

hiatus in the diaphragm.

It is a common finding.

Two main types of hiatus hernia exist: sliding and rolling.

An alternative name for a rolling hernia is ‘para-oesophageal’

The commoner type is the sliding hiatus hernia, where the gastro-oesophageal junction and a

portion of the stomach are situated above the diaphragm The cardiac sphincter is usually

incompetent, so reflux from the stomach to the oesophagus occurs readily and this may cause

oesophagitis, ulceration or peptic stricture. A small sliding hernia may be demonstrated in

most people during a barium meal examination, provided that enough manoeuvres have been

undertaken to increase intra-abdominal pressure. It is, therefore, difficult to assess the

significance of a small hernia with little or no reflux.

In a rolling or para-oesophageal hernia, the fundus of the stomach herniates through the

diaphragm, but the oesophagogastric junction often remains competent below the diaphragm.

A large hernia, particularly one of the para-oesophageal type, may not be reduced when the

patient is in the erect position. In these instances the hiatus hernia will be seen on chest films

and on CT

د.منى

\

radiology L3

SMALL INTESTINE

Imaging techniques

Standard imaging techniques and their indications are:

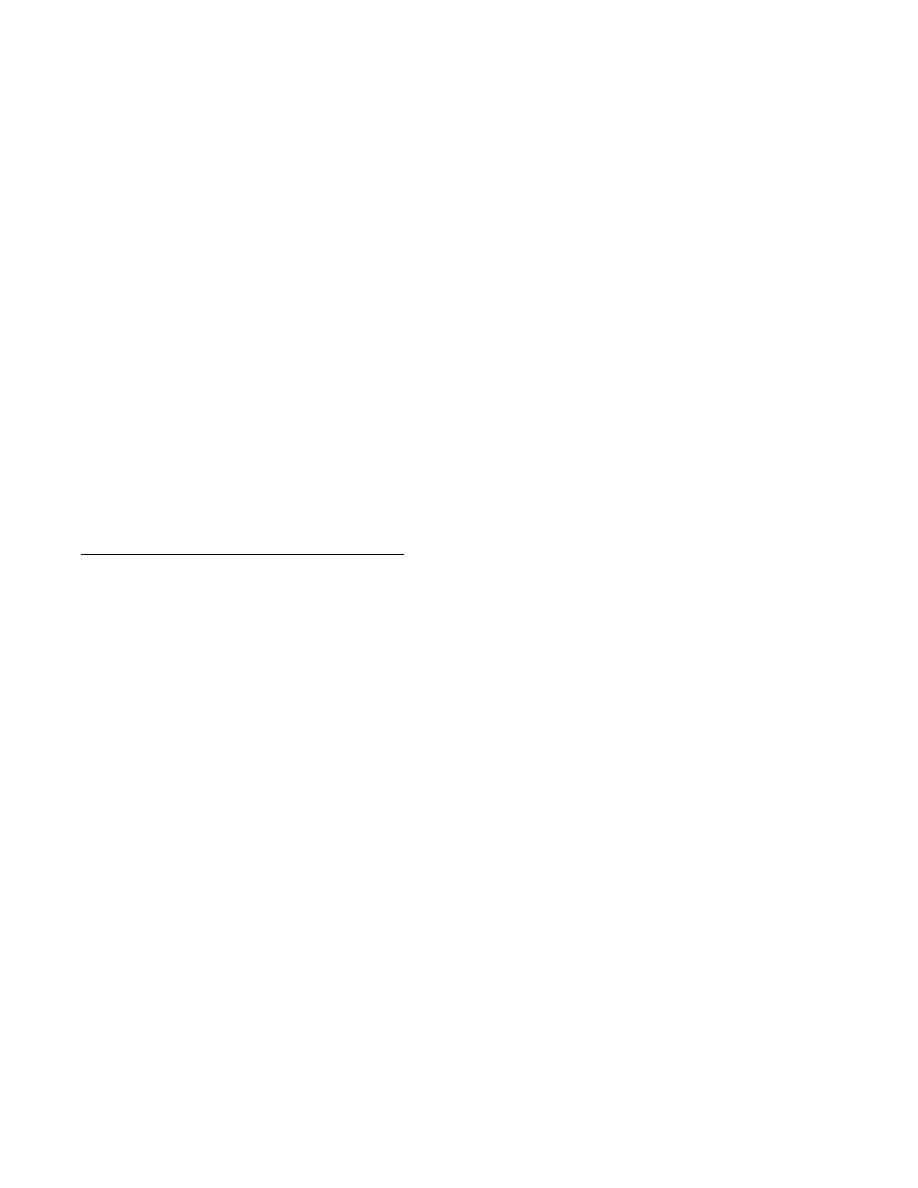

Small bowel follow-through (small bowel meal)

Indications for small bowel follow-through

1. Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn

’s disease)

2. Suspected stricture

3. Malabsorption

4. Enterocutaneous fistulae

5. Post small bowel resection, to assess small bowel length, in short bowel syndrome

6. Malrotation

Computed tomography

has a role in the assessment of small bowel disease as it can show

thickening of the bowel wall, an important sign of inflammatory bowel disease and lymphoma,

and occasionally mucosal irregularity and small bowel neoplasms.

***

The patient fasts for 4

–6 hours prior to the procedure and then may be given oral

Gastrografin or water to delineate the small bowel. In some cases, an intravenous bowel relaxant

is injected.

***

CT enteroclysis may also be performed with contrast being infused into the small bowel via

a nasoduodenal tube, followed by CT. Intravenous iodinated contrast medium is injected to

demonstrate vessels and enhancing structures.

Ultrasound

Demonstrate small bowel thickening and free fluid associated with inflammatory conditions, and can

demonstrate a thickened appendix suggestive of appendicitis and occasionally the presence of an

intussusception.

Magnetic resonance imaging

for assessment

Normal appearances of the small bowel

The normal small intestine occupies the central and lower abdomen, usually framed by the

colon.

The terminal portion of the ileum enters the medial aspect of the caecum through the ileocaecal

valve. As the terminal ileum may be the first site of disease

The barium forms a continuous column defining the diameter of the small bowel, which is

normally not more than 25 mm ( 3 cm)

Transverse folds of mucous membrane project into the lumen of the bowel and barium lies

between these folds, which appear as lucent filling defects of about 2

–3 mm in width.

The mucosal folds are largest and most numerous in the jejunum and tend to disappear in the

lower part of the ileum On CT, the small bowel is seen as multiple loops usually containing oral

water or contrast medium.

The lumen of each loop should not exceed 25 mm.

The wall of the small bowel may not be properly assessed unless the small bowel is

distendedplanes.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Imaging signs of disease of the small intestine

Dilatation

Dilatation usually indicates malabsorption, paralytic ileus or small bowel obstruction . A diameter over

30 mm is definitely abnormal, but it is important to make sure that two overlapping loops are not being

measured

Mucosal abnormality

The mucosal folds become thickened in many conditions (e.g. malabsorption states, oedema or

haemorrhage in the bowel wall) and when inflamed or infiltrated

As mucosal fold thickening occurs in many diseases, it is not possible to make a particular diagnosis

unless other more specific features are present.

Narrowing

The only normal narrowings are those caused by peristaltic waves. They are smooth, concentric and

transient, with normal mucosal folds traversing them and normal bowel proximally. The common

causes of strictures are Crohn

’s disease , tuberculosis and lymphoma. Strictures do not contain normal

mucosal folds and usually result in dilatation of the bowel proximally.

Ulceration

The outline of the small bowel should be smooth apart from the indentation caused by normal mucosal

folds.

Ulcers appear as spikes projecting outwards, which may be shallow or deep .

Ulceration is seen in Crohn

’s disease, tuberculosis and lymphoma.

When there is a combination of fine ulceration and mucosal oedema, a

‘cobblestone’ ppearance may be

seen.

Specific diseases of the small intestine

Crohn’s disease

a disease of unknown aetiology of non-specific chronic granulomatous inflammation, which nearly

always affects the terminal ileum. In addition, it may cause disease in several different parts of the

small and large intestine, often leaving normal intervening bowel, the affected parts being known

as skip lesions.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

The major signs on barium examinations and crosssectional

Imagin

g

1. Strictures, which are extremely variable in length. Sometimes a loop of bowel is so narrow,

either from spasm or oedema and fibrosis in the bowel wall, that its appearance has been called

the

‘string sign’.

2. Contraction of the caecum, which may be seen particularly when there is visible disease in the

terminal ileum.

3. Dilatation of the bowel, which may be seen proximal to narrowed areas.

4. Ulcers; these are sometimes quite deep. Fine ulceration combined with mucosal oedema gives

rise to the so-called

‘cobblestone’ appearance.

5. Thickening, distortion or effacement of mucosal folds.

6. Separation of loops of bowel, due to bowel wall thickening or an inflammatory mass.

7. Fistulae to other small bowel loops, colon, bladder or vagina . When the fistula is between

adjacent loops of small intestine it can be difficult to detect.

8. Signs of malabsorption

Imaging :

1. Ultrasound may identify thickened loops of bowel, abscess collections in the lower

abdomen

2. CT, have a thick-walled appearance with streaky, high density of the surrounding mesenteric fat

due to surrounding oedema and inflammatory change.

When Crohn

’s disease affects the anal canal, a perianal fistula often results.

3. MRI is often used to demonstrate the position and extent of the fistula.

Small bowel ischaemia

Intestinal infarction, a serious life-threatening condition, is caused by occlusion of the superior

mesenteric artery, either due to a thrombosis or an embolus .

There may be thickening and oedema of the wall of the small bowel, and gas may be seen within the

bowel wall.

Perforation may occur, with free gas seen within the peritoneal cavity. There may be air within the

superior mesenteric vein or portal vein system in severe cases. These features are best demonstrated on

a post contrast CT, performed in the arterial and portal venous phase, which will also demonstrate the

arterial anatomy.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis of the small bowel is indistinguishable from Crohn

’s disease on barium examination.

It commonly affects the ileocaecal region and also causes contraction of

the caecum.

On CT, there may be signs of diffuse peritoneal involvement, with ascites, thickening of the omentum,

peritoneal and serosal nodules, and lymph node enlargement.

These appearances may be indistinguishable from a disseminated intraperitoneal malignancy and

ultrasound

or CT-guided biopsy is usually required to establish the

diagnosis.

Lymphoma

The infiltration in the wall of the bowel with lymphoma ,extremely difficult to distinguish

from Crohn

’s disease. Features that may help differentiate the two conditions on barium examinations

are

د.منى

\

radiology L3

small mucosal filling defects due to tumour nodules and displacement of loops caused by enlarged

mesenteric lymph nodes. Enlargement of the liver and spleen may also be present.

CT and ultrasound can show very marked thickening of the bowel wall, which can help differentiate

between Crohn

’s disease and lymphoma.

CT can also demonstrate mesenteric and para aortic lymphadenopathy and lymphomatous deposits in

the liver and spleen.

Malabsorption

A number of disorders result in defective absorption of Foodstuffs, minerals or vitamins. The definitive

test for malabsorption is jejunal biopsy.

The following imaging signs may occur with any of the causes of malabsorption

• Small bowel dilatation, the jejunum being affected more than the ileum.

• Thickening of mucosal folds.

• The barium may be diluted by the excessive fluid in the small bowel and so appears less dense.

The use of barium follow-through in malabsorption is mainly confined to demonstrating a structural

abnormality causing the malabsorption, notably:

• Crohn’s disease.

• Lymphoma.

• Anatomical abnormalities, e.g. decreased length of small bowel available for absorption, such as

surgical resection or a fistula short-circuiting a length of small bowel.

• Stagnation of bowel contents, allowing bacterial overgrowth, which utilizes nutrients from the bowel

lumen, caused by:

– multiple small bowel diverticula (Fig. 6.48)

– a dilated loop cut off from the main stream of the

bowel in which there is delayed filling and emptying

(blind loop)

– a dilated loop proximal to a stricture (stagnant loop).

Acute small bowel obstruction

1. peritoneal adhesions (usually postoperatively or following previous peritoneal inflammation),

2. obstruction in hernial orifices, Crohn

’s disease, at the site of twisting in volvulus,

3. occasionally due to metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma or even primary small bowel tumours.

A barium examination is not carried out in most cases of obstruction as the diagnosis is usually made

on clinical history and examination with the help of plain abdominal films.

Water-soluble contrast is used in preference to barium

LARGE INTESTINE

Imaging techniques

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is now the gold standard for examining the colonic mucosa and may be used for

diagnostic or therapeutic biopsy or resection of mucosal lesions.

Barium enema

Firstly, the bowel is prepared by means of aperients or washout to rid the colon of faecal

material, which might otherwise mask small lesions and cause confusion by simulating polyps.

Although diverticular disease and colonic carcinoma are well demonstrated at barium enema,

CT pneumocolon is increasingly being used following failed colonoscopy.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Instant enemas (water-soluble contrast) are still used in suspected large bowel obstruction to

confirm the diagnosis and also to delineate the level of obstruction in a patient who may be

considered for bowel decompression with a colonic stent, prior to surgery

Computed tomography pneumocolon

the method of choice for identifying malignant tumours of the colon when colonoscopy has

failed as it has the advantage of allowing not only the diagnosis of the tumour but also the

demonstration of metastatic disease.

Neither barium nor Gastrografin is used.

three-dimensional display and viewed as

virtual colonoscopy

.

Sigmoidoscopy

is performed in almost every patient in whom a barium enema or CT

pneumocolon is requested, because lesions in the rectum, especially mucosal abnormalities, may

be missed.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging of the colon is challenging due to movement artefacts from bowel

peristalsis.

MRI is mainly used to evaluate the rectum and anal canal, where movement artefacts are

minimal. No specific patient preparation is required.

Nuclear medicine studies

in patients with chronic constipation.

The presence of inflammation (Ulcerative colitis.)

Normal appearance of the colon

The calibre decreases from the caecum to the sigmoid colon.

The caecum is usually situated in the right iliac fossa, but it may be seen under the right lobe of

the liver or even in the centre of the abdomen if it possesses a long mesentery.

The lips of the ileocaecal valve may project into the caecum and cause a filling defect, which

must not be mistaken for a tumour.

Filling of the terminal ileum and appendix with rectal contrast may occur, but if they do not fill

no significance can be attached to this.

Haustra can usually be recognized in the whole of the colon, although they may be absent in the

descending and sigmoid regions. The outline of the descending colon, apart from the haustra, is

smooth.

Imaging signs of disease of the large intestine

Narrowing of the lumen

Narrowing of the colon may be due pathology:

• inside the lumen of the bowel (e.g. impacted faeces)

• inside the bowel wall (may be due to physiological spasm)

• outside the bowel wall due to compression by an extrinsic mass.

Causes of narrowing of the colonic lumen

1. Carcinoma

2. Diverticular disease

3. Crohn

’s disease

4. Ischaemic colitis

5. Rarer causes:

- Tuberculosis: --lymphogranuloma venereum

—amoebiasis---radiation fibrosis

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Neoplastic strictures

have shouldered edges, an irregular lumen and are rarely more than 6 cm in

length

whereas benign strictures

classically have tapered ends, a relatively smooth outline and may be

of any length.

Ulceration

may be seen in strictures due to Crohn

’s disease, and sacculation of the colon is a

feature of ischaemic strictures.

Narrowing due to diverticular disease

It is sometimes impossible to distinguish a stricture due

to a carcinoma in an area of diverticular disease from a stricture due to diverticular disease.

• The site of the stricture can help in limiting the differential diagnosis. Strictures due to diverticular

disease are almost always confined to the sigmoid colon. Ischaemic strictures are usually centred

somewhere between the splenic flexure and the sigmoid colon. Crohn

’s disease and tuberculosis have a

predilection for the caecum.

Extrinsic compression

by a mass arising outside the wall of the bowel causes a smooth

narrowing of the colon at barium enema examination, frequently from one side only, and often

displaces the colon, e.g. ovarian and uterine masses. Extrinsic compression causing a smooth

indentation on the caecum may be seen with a mucocele of the appendix, appendix abscess or an

inflammatory mass in Crohn

’s disease.

Dilatation

Double-contrast barium enema and CT pneumocolon examinations both involve distending the

colon

The causes of dilatation of the colon are:

1.

Obstruction.

2.

Paralytic ileus.

3.

Volvulus

.

4.

Ulcerative colitis

with toxic dilatation

5.

Hirschsprung

’

s disease

and

megacolon

.

Filling defects

1. Filling defects in the colon, as elsewhere in the GI tract, may be intraluminal, arise from the wal

or be due to pressure from an extrinsic mass.

2. A localized filling defect is likely to be a polyp or a neoplasm.

3. Faeces cause a filling defect which can be very difficult to distinguish from a polyp or tumour

Faeces have no attachment to the wall of the bowel, are completely surrounded by barium or air,

and move according to the position of the patient

4. Intramural haemorrhage, oedema or air in the wall of the colon (pneumatosis coli) all cause

multiple, smooth filling defects arising from the wall of the bowel.

5. A unique type of filling defect is seen in intussusceptions.

Ulceration

Ulcers of the colonic mucosa can be recognized on barium enema as small projections from the

lumen into the wall of the bowel, causing the normally smooth outline of the colon to have a

fuzzy or shaggy appearance

The two major causes of ulceration are ulcerative colitis and Crohn

’s disease. Rarer causes

include tuberculosis and amoebic and bacillary dysentery.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Specific diseases of the colon

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a disease of unknown aetiology characterized by inflammation and ulceration of

the colon. The disease always involves the rectum. When more extensive it extends in continuity

around the colon, sometimes affecting the whole colon.

Signs :

1. The cardinal radiological sign is widespread ulceration The ulcers are usually shallow, but in

severe cases may be quite deep.

2. In all but the milder cases, there is loss of the normal colonic haustra in the affected portions of

the colon.

3. Oedema of the perirectal tissues causes widening of the space between the sacrum and the

rectum.

4. Narrowing and shortening of the colon, giving the appearance of a rigid tube,

5. in advanced disease Pseudopolyps are small filling defects projecting into the lumen of the

bowel, formed by swollen mucosa in between the areas of ulceration.

6. Strictures are rare, and, when present, are likely to be due to carcinoma; the incidence of colonic

carcinoma in longstanding ulcerative colitis is significantly increased.

7. On CT, the bowel wall may be thickened.

8. In chronic ulcerative colitis there is visible fatty infiltration in the submucosa, resulting in a

‘target sign’ appearance.

9. When the whole colon is involved, the terminal ileum may become dilated. As the ileocaecal

valve in this situation is incompetent,

10. Toxic dilatation (toxic megacolon) is a serious complication

11. Barium enema and CT pneumocolon should be avoided in the presence of toxic dilatation

owing to the risk of perforating the colon, a contraindication that also applies to colonoscopy.

Crohn

’

s disease

chronic granulomatous condition of unknown aetiology, which may affect any part of the GI tract, but

most frequently involves the lower ileum and the colon. The colon may be the only part of the

alimentary tract to be involved, but usually the disease affects the small bowel if the colon is involved.

Signs :

1. At an early stage in the disease, the findings at barium enema are loss of haustration,

2. narrowing of the lumen of the bowel

3. shallow ulceration.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

4. This criss-crossing ulceration combined with mucosal oedema may give rise to a

‘cobblestone’

appearance of the mucosa

Later,the ulcers become deeper and may track in the submucosa

5. The ulcers may be very deep, penetrating into the muscle layer, when they are described as

‘rose-thorn ulcers’ or deep fissures.

6. The deep ulceration in Crohn

’s disease may lead to the formation of intra- and extramural

abscesses.

7. Fistulae are an important complication.

8. The additional features visible at CT are thickening of the bowel wall, strands in the surrounding

fat, fistulae and extracolonic fluid collections.

9. Strictures are a common finding in Crohn

’s disease

10. The disease is not always circumferential; one of the features that distinguish it from ulcerative

colitis is that it may involve only one portion of the circumference of the bowel.

11. Another important diagnostic feature is the presence of the so-called

‘skip lesion’, namely areas

of disease with intervening normal bowel. Skip lesions are virtually diagnostic of Crohn

’s

disease. However, the entire colon may be involved or the disease may be limited to just one

segment.

12. There is a predilection for the caecum and terminal ileum.

13. The rectum is often spared

– another important differentiating feature from ulcerative colitis.

14. Fistulae may also occur between the colon and the small bowel, bladder or vagina, which may

be demonstrated on water-soluble contrast studies or MRI

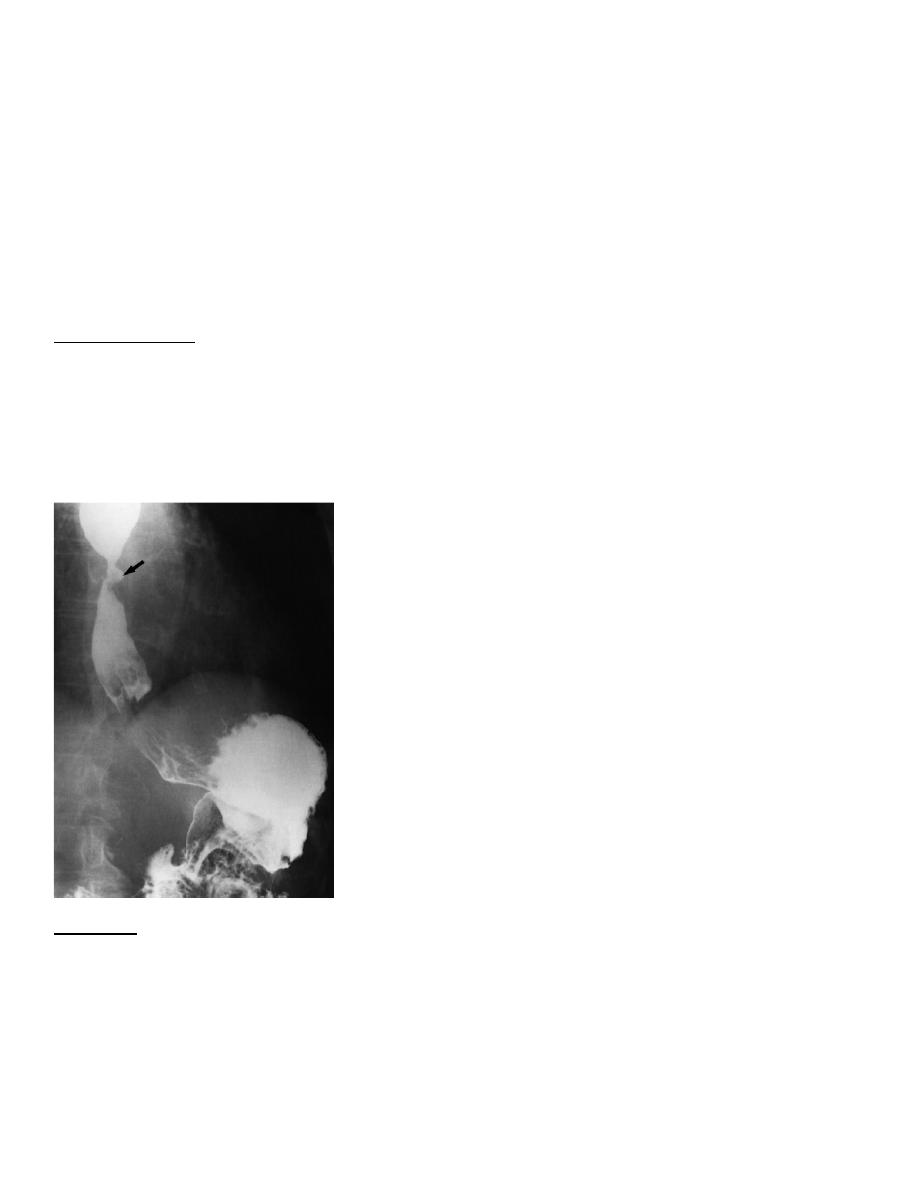

Diverticular disease

sac-like out-pouchings of mucosa through the muscular layer of the bowel wall. They are associated

with hypertrophy of the muscle layer and are probably due to herniation of mucosa through areas of

weakness where blood vessels penetrate the muscle.

Diverticula are very common, particularly in the elderly.

They are seen in all parts of the colon, but are commonest in the sigmoid colon.

The term diverticulitis is used when infection of the affected segment causes symptoms such as

sepsis, diarrhoea or obstruction.

The diverticula, when filled with barium, are seen as spherical out-pouchings with a narrow

neck .

د.منى

\

radiology L3

The colon may also show a

‘saw-tooth’ serrated appearance from hypertrophy of the muscle

coats.

Some diverticula may not fill; when inflammation occludes the necks of the diverticula.

On CT, the affected loop of bowel appears thick-walled and there is stranding of the

surrounding fat due to oedema and inflammatory change .

A diverticulum may perforate, resulting in a pericolic abscess or fistula into the bladder, small

bowel or vagina. This is recognized by noting barium outside the colon, either in the pericolic

region or within the structure to which the fistula has occurred.

An abscess is most readily diagnosed with CT.

Occasionally, diverticula perforate directly into the peritoneal cavity causing peritonitis, and free

intraperitoneal air should be looked for on a plain abdominal film if necessary.

A stricture with or without local abscess formation may occur

Ischaemic colitis

Acute infarction of the large bowel is very rare.

mucosal oedema and haemorrhage, and usually resolve

If suspected, a CT arteriogram is very helpful in not only demonstrating the presence of bowel

abnormalities (e.g. strictures), but

On barium studies, mucosal haemorrhage and oedema may be recognized by observing

multiple, smooth indentations into the lumen of the bowel, resembling thumb prints

If stricture formation occurs, the stricture will be smooth and have tapered ends. The site is

usually, but not always, centred between the splenic flexure and the sigmoid colon because these

are the regions of the colon with the most vulnerable blood supply

Sacculations may be seen arising from one side of the strictured area

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Colorectal tumours

Polyps

means a small mass of tissue arising from the wall of the bowel projecting into the lumen.

They are best investigated by endoscopy, but may be found at barium enema or CT

pneumocolon.

It is often impossible on radiological grounds to exclude frank malignancy in a polyp in an

adult. However, only a tiny minority of polyps less than 1 cm in size, and very few less than 2

cm, are cancers.

The features that suggest malignancy are a diameter of more than 2 cm, a short thick stalk or an

irregular surface.

Polyps may be sessile or on a stalk, single or multiple.

The common polyps are:

Adenomatous polyps

are benign neoplasms but have a predisposition to malignant change.

They are, therefore, removed endoscopically when discovered, regardless of whether or not an

individual polyp is believed to be responsible for symptoms.

found most frequently in the rectosigmoid region.( single or multiple )

In

familial polyposis

they are numerous and one or more will, in time, undergo malignant

change

Villous adenomas

are benign sessile tumours showing a sponge-like appearance owing to

barium trapped between the villous strands. common sites are the rectum and caecum. There is a

high incidence of malignant change.

Polypoid adenocarcinomas

.

Juvenile polyps

. Almost all isolated polyps in children are benign. They are probably

developmental in origin.

Inflammatory polyps (pseudopolyps)

are seen in ulcerative colitis.

Hyperplastic or metaplastic polyps

.

د.منى

\

radiology L3

Carcinoma

Carcinomas may arise anywhere in the colon and rectum but they are commonest in the

rectosigmoid region and caecum.

The appearance and behaviour of a carcinoma in these two sites are usually quite different. The

patient with a rectosigmoid carcinoma often has an annular stricture and presents with alteration

in bowel habit and obstruction, whereas with a caecal carcinoma the tumour can become very

large without obstructing the bowel, so anaemia and weight loss are the common presenting

features.

A barium enema shows annular carcinomas as an irregular stricture with shouldered edges (see

Such strictures are rarely more than 6 cm in length. The polypoid or fungating carcinoma causes

an irregular filling defect projecting into the lumen of the bowel.

Computed tomography particularly CT pneumocolo, recognized as thickening of the bowel

wall and an irregular narrowing of the lumen of the colon.

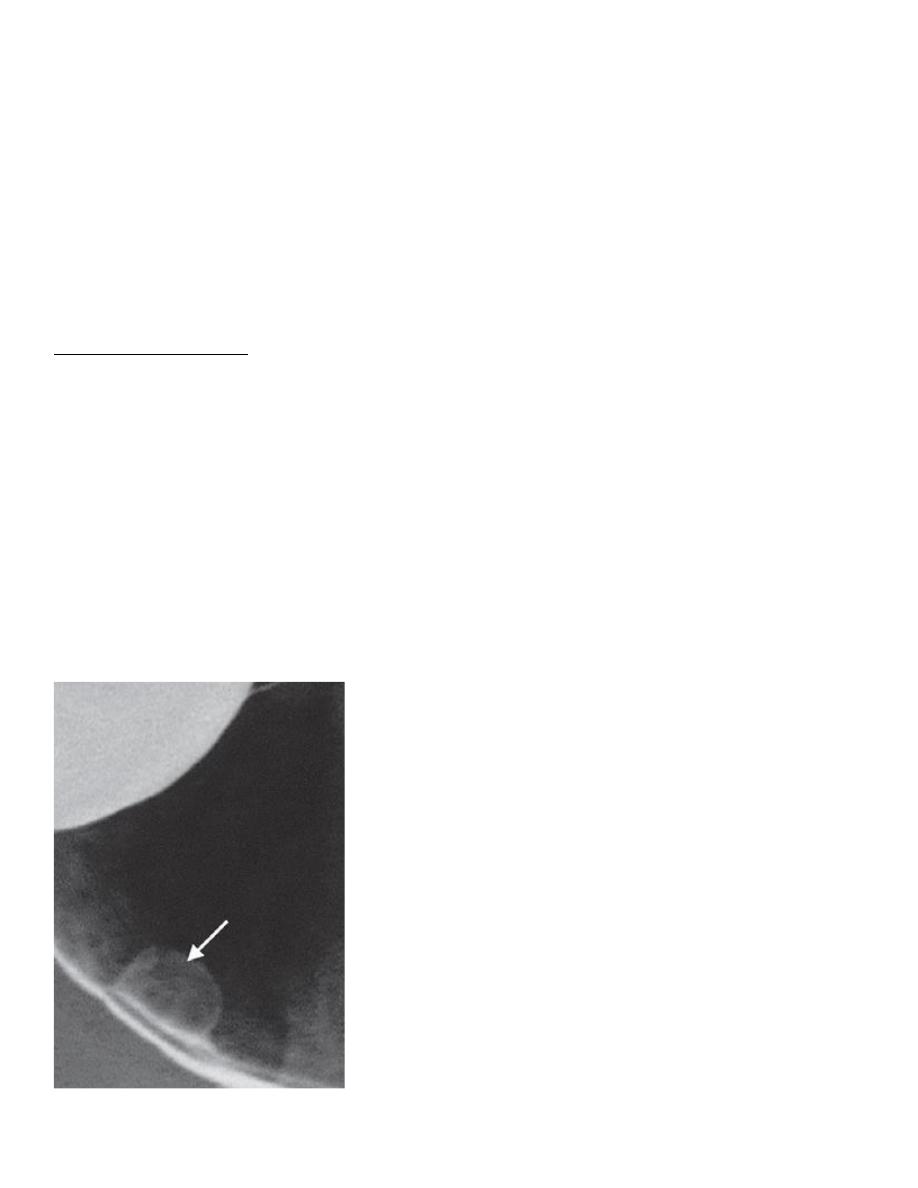

Magnetic resonance imaging is the method of choice for local extent of

rectal carcinoma

. The

mesorectal fascia is an important anatomical landmark as it represents the surgical plane of

dissection during rectal cancer surgery.

Staging colorectal carcinoma

.

CT is used to demonstrate distant metastases to the liver or lungs and to identify para-aortic

nodal disease.

CT can also inform on the local staging of a colonic tumour (e.g. infiltration into abdominal or

pelvic organs) although the definitive extent of local disease may not be known until the time of

surgery

FDG-PET/CT is not currently used routinely for initial staging of colorectal cancer, but it is

more sensitive than CT in the detection of metastatic sites of disease and is used in suspected

recurrent disease in patients who are to be considered for potential curative surgery (e.g. hepatic

resection for liver metastases) to ensure there are no other sites of recurrence.

Noor Rahman