1

4th stage

يةٌطاب

Lec-7

.د

اسواعيل

18/10/2015

Motility disorders of oesophagus

A. Primary

1. Pharyngeal pouch

This occurs because of incoordination of

swallowing within the pharynx, which leads to

herniation through the cricopharyngeus muscle

and formation of a pouch.

It is rare, and it usually develops in middle life but can arise at any age.

Many patients have no symptoms, but regurgitation, halitosis and

dysphagia can be present. Some notice gurgling in the throat after

swallowing. The investigation of choice is a barium swallow, which

demonstrates the pouch and reveals incoordination of swallowing, often

with pulmonary aspiration. Endoscopy may be hazardous, since the

instrument may enter and perforate the pouch. Surgical myotomy

(‘diverticulotomy’), with or without resection of the pouch, is indicated

in symptomatic patients.

2. Achalasia of the oesophagus

Achalasia is characterised by: a hypertonic lower oesophageal sphincter,

which fails to relax in response to the swallowing wave failure of

propagated oesophageal contraction, leading to progressive dilatation of

the gullet. The cause is unknown. Defective release of nitric oxide by

inhibitory neurons in the lower oesophageal sphincter has been

reported, and there is degeneration of ganglion cells within the

sphincter and the body of the oesophagus. Loss of the dorsal vagal

nuclei within the brainstem can be demonstrated in later stages.

Infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in Chagas’ disease causes a syndrome

that is clinically indistinguishable from achalasia.

2

Clinical features

The presentation is with dysphagia. This develops slowly, is initially

intermittent, and is worse for solids and eased by drinking liquids, and

by standing and moving around after eating. Heartburn does not occur

because the closed oesophageal sphincter prevents gastro-oesophageal

reflux. Some patients experience episodes of chest pain due to

oesophageal spasm. As the disease progresses, dysphagia worsens, the

oesophagus empties poorly and nocturnal pulmonary aspiration

develops. Achalasia predisposes to squamous carcinoma of the

oesophagus.

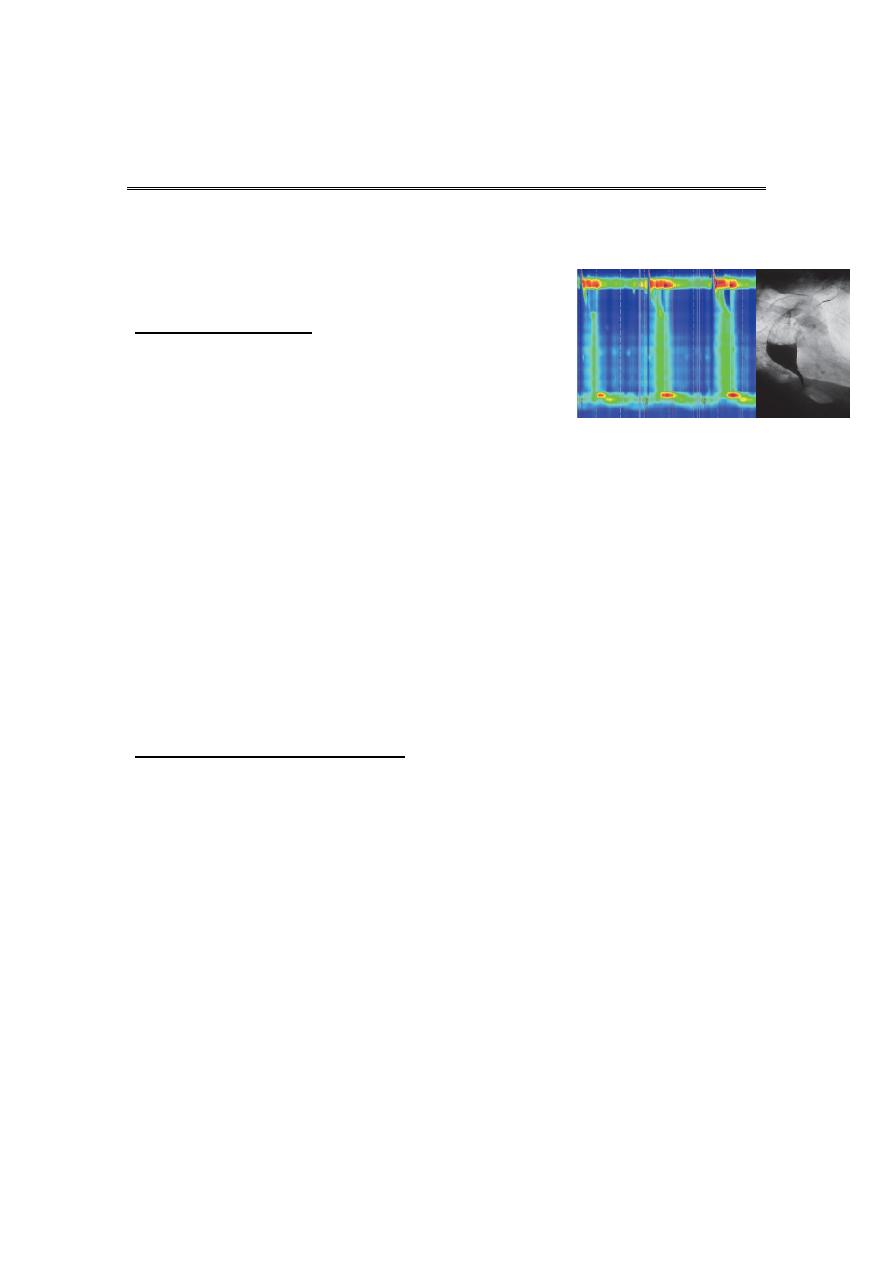

Investigations:

Endoscopy should always be carried out because carcinoma of the cardia

can mimic the presentation and radiological and manometric features of

achalasia (‘pseudo-achalasia’). A barium swallow shows tapered

narrowing of the lower oesophagus and, in late disease, the oesophageal

body is dilated, aperistaltic and food filled. Manometry confirms the high

pressure, non-relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter with poor

contractility of the oesophageal body

Management

Endoscopic

Forceful pneumatic dilatation using a 30–35-mm diameter

fluoroscopically positioned balloon disrupts the

oesophageal sphincter and improves symptoms in 80%

of patients. Some patients require more than one dilatation

but those needing frequent dilatation are best

treated surgically.

Endoscopically directed injection of botulinum toxin into the lower

oesophageal sphincter induces clinical remission but relapse is common.

3

Surgical

Surgical myotomy (Heller’s operation), performed either

laparoscopically or as an open operation, is effective but

is more invasive than endoscopic dilatation. Both pneumatic

dilatation and myotomy may be complicated by

gastro-oesophageal reflux, and this can lead to severe

oesophagitis because oesophageal clearance is so poor.

For this reason, Heller’s myotomy is accompanied by a

partial fundoplication anti-reflux procedure. PPI therapy

is often necessary after surgery. Recently, a complex

endoscopic technique has been developed in specialist

centres (peroral endoscopic myotomy, POEM).

3. Other oesophageal motility disorders

Diffuse oesophageal spasm presents in late middle age with episodic

chest pain that may mimic angina, but is sometimes accompanied by

transient dysphagia. Some cases occur in response to gastro-

oesophageal reflux. Treatment is based upon the use of PPI drugs when

gastro-oesophageal reflux is present. Oral or sublingual nitrates or

nifedipine may relieve attacks of pain. The results of drug therapy are

often disappointing, as are the alternatives: pneumatic dilatation and

surgical myotomy. ‘Nutcracker’ oesophagus is a condition in which

extremely forceful peristaltic activity leads to episodic chest pain and

dysphagia. Treatment is with nitrates or nifedipine. Some patients

present with oesophageal motility disorders which do not fit into a

specific disease entity. The patients are usually elderly and present with

dysphagia and chest pain. Manometric abnormalities, ranging from poor

peristalsis to spasm, occur. Treatment is with dilatation and/or

vasodilators for chest pain

4

B. Secondary causes of oesophageal dysmotility

In systemic sclerosis or CREST syndrome, the muscle of the oesophagus

is replaced by fibrous tissue, which causes failure of peristalsis leading to

heartburn and dysphagia. Oesophagitis is often severe, and benign

fibrous strictures occur. These patients require long-term therapy with

PPIs. Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis and myasthenia gravis may

also cause dysphagia.

Common causes of benign oesophageal stricture

Benign oesophageal stricture is usually a consequence of gastro-

oesophageal reflux disease and occurs most often in elderly patients

who have poor oesophageal clearance. Rings, due to submucosal

fibrosis, are found at the oesophago-gastric junction (‘Schatzki ring’) and

cause intermittent dysphagia, often starting in middle age. A post-cricoid

web is a rare complication of iron deficiency anaemia (Paterson–Kelly or

Plummer– Vinson syndrome), and may be complicated by the

development of squamous carcinoma. Benign strictures can be treated

by endoscopic dilatation, in which wireguided bougies or balloons are

used to disrupt the fibrous tissue of the stricture.

Other uncommon causes of oesophageal stricture

• Eosinophilic oesophagitis

• Extrinsic compression from bronchial carcinoma

• Corrosive ingestion

• Post-operative scarring following oesophageal resection

• Post-radiotherapy

• Following long-term nasogastric intubation

• Bisphosphonates

Tumours of the oesophagus

5

Benign tumours

The most common is a leiomyoma. This is usually asymptomatic but may

cause bleeding or dysphagia.

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Squamous oesophageal cancer is relatively rare in Caucasians but is

more common in Iran, parts of Africa and China. Squamous cancer can

occur in any part of the oesophagus, and almost all tumours in the upper

oesophagus are squamous cancers. Adenocarcinomas typically arise in

the lower third of the oesophagus from Barrett’s oesophagus or from

the cardia of the stomach. The incidence is increasing , this is possibly

because of the high prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux and

Barrett’s oesophagus in populations. Despite modern treatment, the

overall 5-year survival of patients presenting with

oesophageal cancer is only 13%.

Squamous carcinoma: aetiological factors (risk factors)

Smoking

• Alcohol excess

• Chewing betel nuts or tobacco

• Achalasia of the oesophagus

• Coeliac disease

• Post-cricoid web

• Post-caustic stricture

• Tylosis (familial hyperkeratosis of palms and soles)

6

Risk factors for adenocarcinoma (lower part) of oesophagus

1. Barrett’s oesophagus.

2. Smoking.

3. Obesity.

Clinical features

Most patients have a history of progressive, painless dysphagia for solid

foods. Others present acutely because of food bolus obstruction. In late

stages, weight loss is often extreme; chest pain or hoarseness suggests

mediastinal invasion. Fistulation between the oesophagus and the

trachea or bronchial tree leads to coughing

after swallowing, pneumonia and pleural effusion. Physical signs may be

absent but, even at initial presentation, cachexia, cervical

lymphadenopathy or other evidence of metastatic spread is common.

Investigations

The investigation of choice is upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with

biopsy. A barium swallow demonstrates the site and length of the

stricture but adds little useful information. Once a diagnosis has been

made, investigations should be performed to stage the tumour and

define operability. Thoracic and abdominal CT, often combined with

positron emission tomography (CT-PET), should be carried out to identify

metastatic spread and local invasion. Invasion of the aorta, major

airways or coeliac axis usually precludes surgery, but patients with

resectable disease on imaging should undergo EUS to determine the

depth of penetration of the tumour into the oesophageal wall and to

detect locoregional lymph node involvement

These investigations will define the TNM stage of the disease

7

Management

The treatment of choice is surgery if the patient presents at a point at

which resection is possible. Patients with tumours that have extended

beyond the wall of the oesophagus (T3) or which have lymph node

involvement (N1) have a 5-year survival of around 10%. However, this

figure improves significantly if the tumour is confined to the

oesophageal wall and there is no spread to lymph nodes. Overall survival

following ‘potentially curative’ surgery (all macroscopic tumour

removed) is about 30% at 5 years, but recent studies have

suggested that this can be improved by neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Although squamous carcinomas are radiosensitive, radiotherapy alone is

associated with a 5-year survival of only 5%, but combined

chemoradiotherapy for these tumours can achieve 5-year survival rates

of 25–30%. Approximately 70% of patients have extensive disease at

presentation; in these, treatment is palliative and should focus on relief

of dysphagia and pain. Endoscopic laser therapy or self-expanding

metallic stents can be used to improve swallowing. Palliative

radiotherapy may induce shrinkage of both squamous cancers and

adenocarcinomas but symptomatic response may be slow. Quality of life

can be improved by nutritional support and appropriate analgesia.

Perforation of the oesophagus

The most common cause is endoscopic perforation complicating

dilatation or intubation. Malignant, corrosive or post-radiotherapy

strictures are more likely to be perforated than peptic strictures. A

perforated peptic stricture is managed conservatively using broad-

spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition; most cases heal within

days. Malignant, caustic and radiotherapy stricture perforations require

resection or stenting. Spontaneous oesophageal perforation

(‘Boerhaave’s syndrome’) results from forceful vomiting and retching.

Severe chest pain and shock occur as oesophago-gastric contents enter

the mediastinum and thoracic cavity. Subcutaneous emphysema, pleural

effusions and pneumothorax develop. The diagnosis can be made using

a water-soluble contrast swallow but, in difficult cases, both CT and

careful endoscopy (usually in an intubated patient) may be required.

8

Treatment is surgical. Delay in diagnosis is a key factor in the high

mortality associated with this condition.

إى

حظي كدلي

ك

فىق

شىن

ٍثروً

.....

ثن لالىا لحفاة

يىم ريح

ٍاجوعى

..... ٍصعب االهر عليهن للت يا لىهي اتركى

إى

ٍتن تسعدوًا فيك يبر ٍامشا يه

^^