4

th

year

Systemic pathology

GIT

Dr. mohamed sabaa ch.

M.B.CH.B Ms.Pathology

THE ORAL CAVITY & OROPHARYNX

Many pathological processes can affect the

constituents of the oral cavity. The more important

and frequent conditions will covered in this lecture.

Diseases involving the teeth and related structures

will not be discussed.

PROLIFERATIVE LESIONS

The most common proliferative lesions of the oral

cavity are

1. Irritation Fibroma and Ossifying fibroma

2. Pyogenic granuloma

3. Peripheral giant cell granuloma

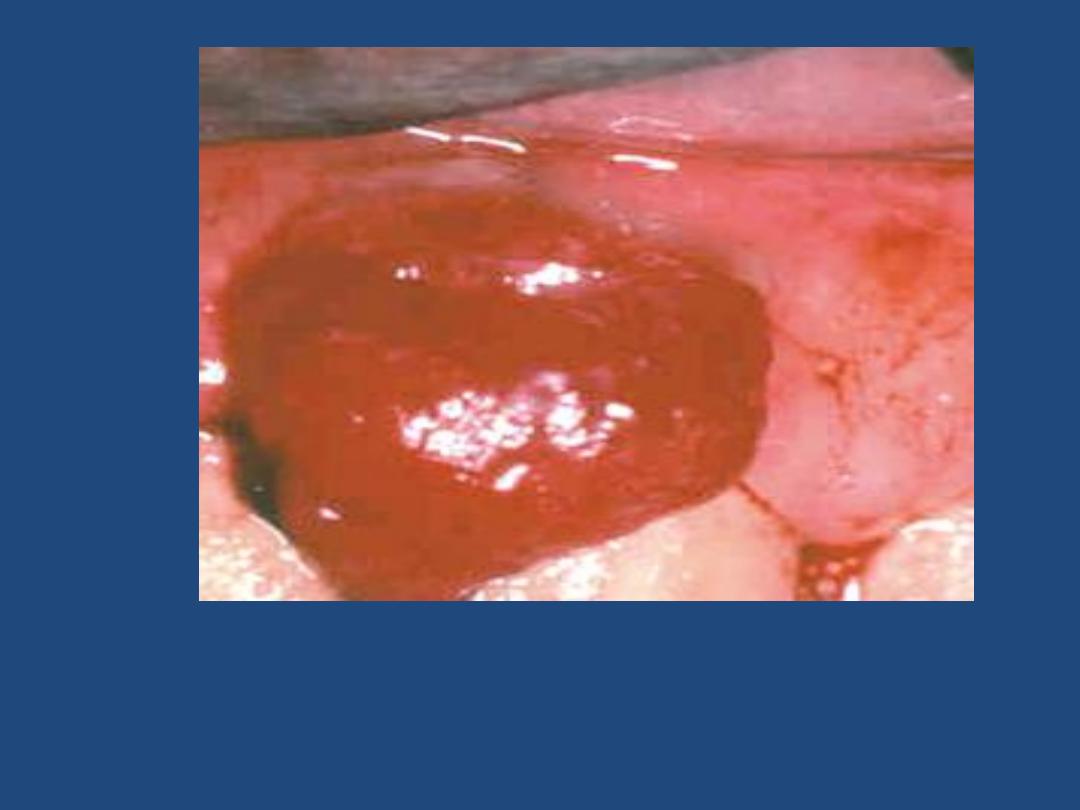

Pyogenic granuloma (granuloma pyogenicum) is a

highly vascular lesion that is usually seen in the

gingiva of children, young adults, and pregnant

women (pregnancy tumor). The lesion is typically

ulcerated and bright red in color (due to rich

vascularity) Microscopically there is vascular

proliferation similar to that of granulation tissue.

The lesion either regresses (particularly after

pregnancy), or undergoes fibrous maturation and

may develop into ossifying fibroma.

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Inflammatory ulcerations

The most common inflammatory ulcerations of the

oral cavity are

1. Traumatic

2. Aphthous

3. Herpetic

Traumatic ulcers, usually the result of trauma (e.g. fist

fighting) or licking a jagged tooth.

Aphthous ulcers are extremely common, single or

multiple, painful, recurrent, superficial, ulcerations of

the oral mucosa. The ulcer is covered by a thin yellow

exudate and rimmed by a narrow zone of erythema.

Herpetic ulcers (see under herpes simplex infection)

INFECTIONS

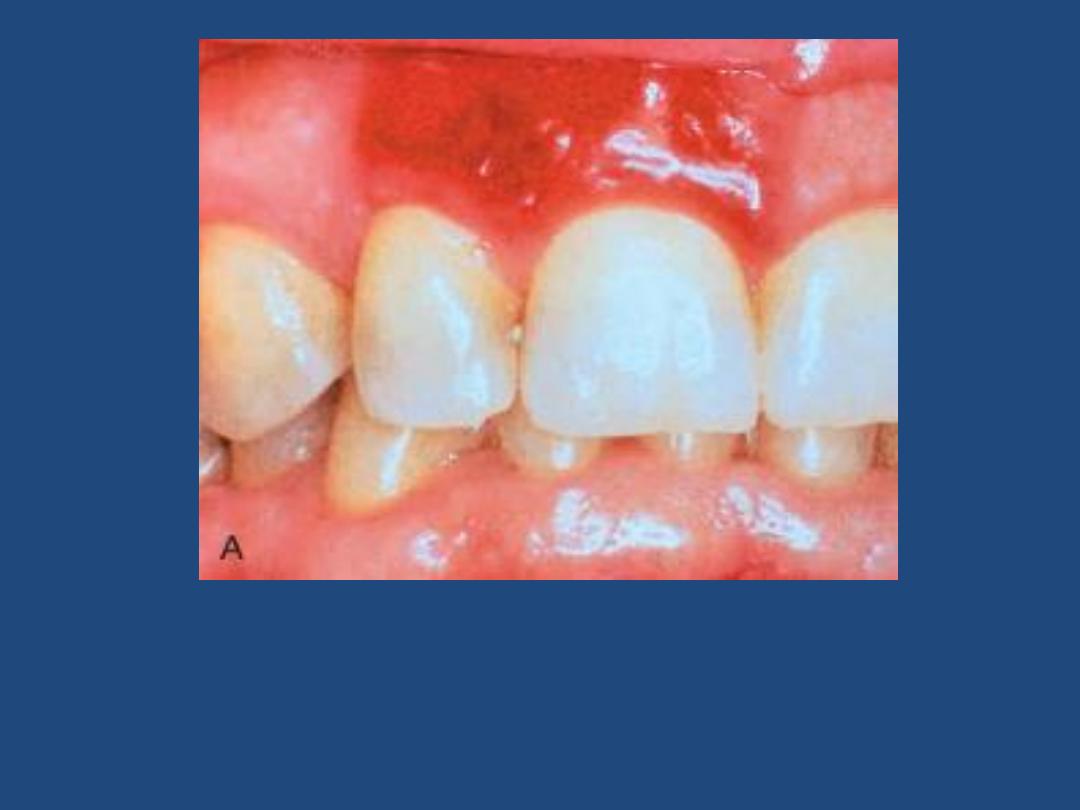

1. Herpes simplex infections

Most of these are caused by herpes simplex virus

(HSV) type 1 & sometimes 2. Primary HSV infection

typically occurs in children aged 2 to 4 years; is often

asymptomatic, but sometime presents as acute

herpetic gingivostomatitis, characterized by vesicles

and ulcerations throughout the oral cavity. The great

majority of affected adults harbor latent HSV-1 (the

virus migrates along the regional nerves and

eventually becomes dormant in the local ganglia

e.g., the trigeminal)

In some individuals, usually young adults, the virus becomes

reactivated to produce the common but usually mild cold

sore.

Factors activating the virus include

1. Trauma

2. Allergies

3. Exposure to ultraviolet light (sunlight)

4. Upper respiratory tract infections

5. Pregnancy

6. Menstruation

7. Immunosuppression

The viral infection is associated with intracellular and

intercellular edema, yielding clefts that may become

transformed into vesicles. The vesicles range from a few

millimeters to large ones that eventually rupture to yield

extremely painful, red-rimmed, shallow ulcerations.

2. Other Viral Infections

These include:

-

Herpes zoster

-

EBV (infectious mononucleosis)

-

CMV

-

Enterovirus

-

Measles

3. Oral Candidiasis (thrush)

This is the most common fungal infection of

the oral cavity. The thrush is a grayish white,

superficial, inflammatory psudomembrane

composed of the fungus enmeshed in a

fibrino-suppurative exudates. This can be

readily scraped off to reveal an underlying red

inflammatory base

The fungus is a normal oral flora but causes

troubles only

1. In the setting of immunosuppression (e.g.

diabetes mellitus, organ or bone marrow transplant

recipients, neutropenia, cancer chemotherapy, or

AIDS) or

2. When broad-spectrum antibiotics are taken;

these eliminate or alter the normal bacterial flora

of the mouth.

3. In infants, where the condition is relatively

common, presumably due to immaturity of the

immune system in them.

4. Deep Fungal Infections

Some fungal infections may extends deeply to

involve the muscles & bones in relation to oral

cavity. These include, among others,

histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and

aspergillosis.

The incidence of such infections has been

increasing due to increasing number of

patients with AIDS, therapies for cancer, &

organ transplantation

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS OF SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Many systemic diseases are associated with oral lesions

& it is not uncommon for oral lesions to be the first

manifestation of some underlying systemic condition.

Scarlet fever: strawberry tongue: white coated tongue

with hyperemic papillae projecting

2. Measles: Koplik spots: small whitish ulcerations

(spots) on a reddened base, about Stensen duct

3. Diphtheria: dirty white, fibrinosuppurative, tough

pseudomembrane over the tonsils and retropharynx

4. AIDS

a. opportunistic oral infections: herpesvirus, Candida,

other fungi

b. Kaposi sarcoma

c. hairy leukoplakia

5. AML (especially monocytic leukemia):

enlargement of the gingivae + periodontitis

6. Melanotic pigmentation

a. Addison disease

b. hemochromatosis

c. fibrous dysplasia of bone

7. Pregnancy: pyogenic granuloma ("pregnancy

tumor")

TUMORS AND PRECANCEROUS LESIONS

Many of the oral cavity tumors (e.g., papillomas,

hemangiomas, lymphomas) are not different

from their homologous tumors elsewhere in the

body. Here we will consider only oral squamous

cell carcinoma and its associated precancerous

lesions.

Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia are considered

premalignant lesions of squamous cell

carcinoma.

Leukoplakia

is a white patch that cannot be scraped off and

cannot be attributed clinically or microscopically

to any other disease i.e. if a white lesion in the

oral cavity can be given a specific diagnosis it is

not a leukoplakia. As such, white patches caused

by entities such as candidiasis are not

leukoplakias. All leukoplakias must be considered

precancerous (have the potential to progress to

squamous cell carcinoma) until proved otherwise

through histologic evaluation.

Erythroplakias

are red velvety patches that are much less

common, yet much more serious than

leukoplakias. The incidence of dysplasia and

thus the risk of complicating squamous cell

carcinoma is much more frequent in

erythroplakia compared to leukoplakias. Both

leukoplakia and erythroplakia are usually found

between ages of 40 and 70 years, and are much

more common in males than females. The use of

tobacco (cigarettes, pipes, cigars, and chewing

tobacco) is the most common incriminated

factor.

Squamous cell carcinoma

The vast majority (95%) of cancers of the head

and neck are squamous cell carcinomas; these

arise most commonly in the oral cavity. The 5-

year survival rate of early-stage oral cancer is

approximately 80%, but this drops to about 20%

for late-stage disease. These figures highlight

the importance of early diagnosis & treatment,

optimally of the precancerous lesions.

The pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma is

multifactorial.

1. Chronic smoking and alcohol consumption

2. Oncogenic variants of human papilloma virus (HPV).

It is now known that at least 50% of oropharyngeal

cancers, particularly those of the tonsils and the base

of tongue, harbor oncogenic variants of HPV.

3. Inheritance of genomic instability; a family history

of head and neck cancer is a risk factor.

4. Exposure to actinic radiation (sunlight) & pipe

smoking are known predisposing factors for cancer of

the lower lip.

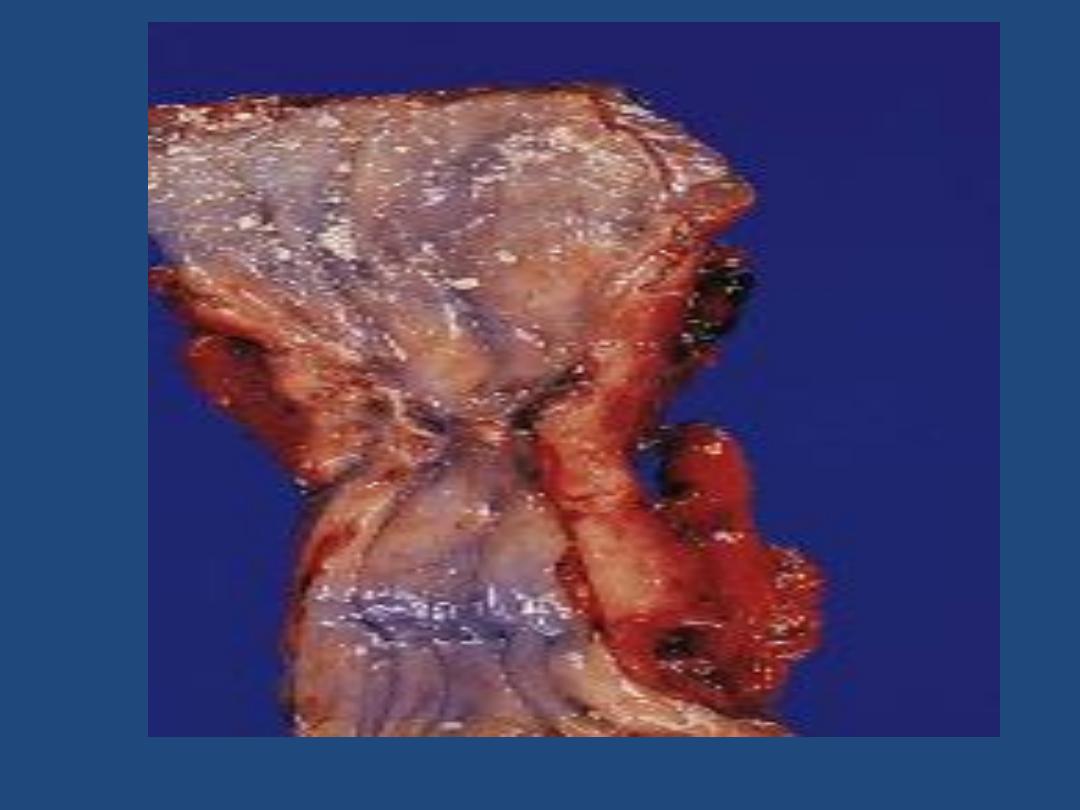

Gross features

Squamous cell carcinoma may arise anywhere in the

oral cavity, but the favored locations are

1. The tongue

2. Floor of mouth

3. Lower lip

4. Soft palate

5. Gingiva

In the early stages, cancers of the oral cavity appear

as roughened areas of the mucosa. As the lesion

enlarges, it typically appears as either an ulcer or a

protruding mass (fungating).

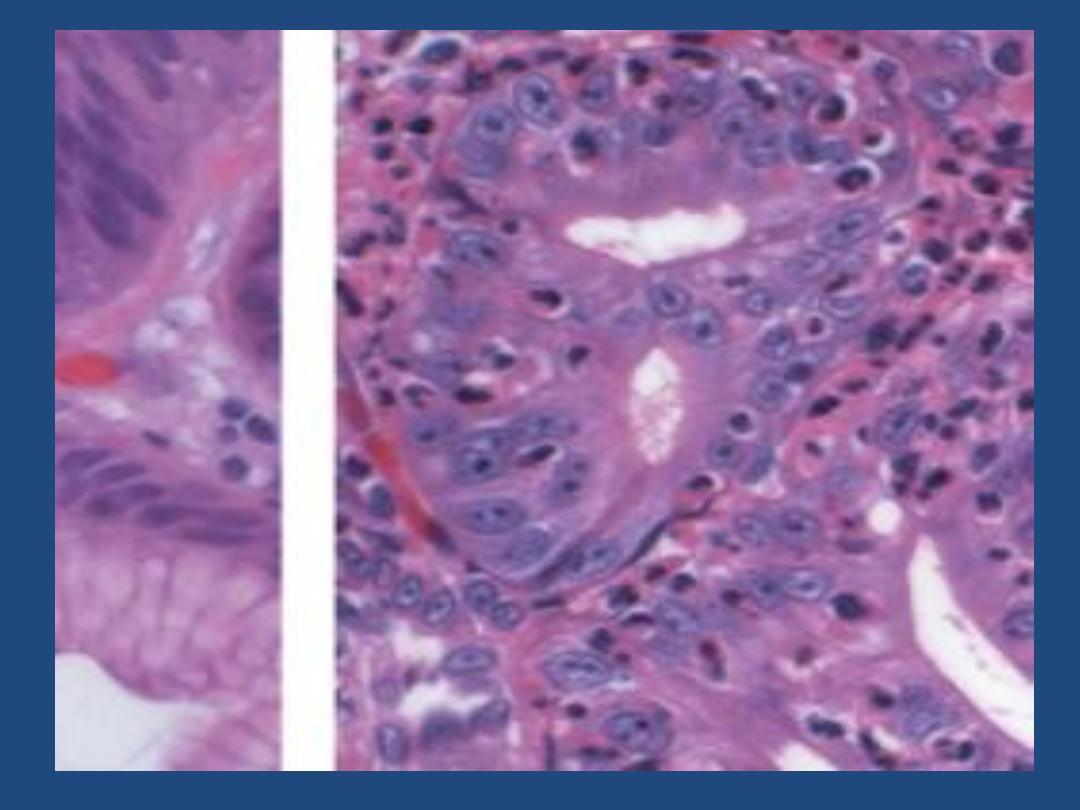

Microscopic features

Early there is full-thickness dysplasia (carcinoma

in situ) followed by invasion of the underlying

connective tissue stroma.

The grade varies from from well-differentiated

keratinizing to poorly differentiated.

As a group, these tumors tend to infiltrate and

extend locally before they eventually metastasize

to cervical lymph nodes and more remotely. The

most common sites of distant metastasis are

mediastinal lymph nodes, lung, liver and bones

SALIVARY GLANDS

There are three major salivary glands—parotid,

submandibular, and sublingual. Additionally, there

are numerous minor salivary glands distributed

throughout the mucosa of the oral cavity.

Xerostomia refers to dry mouth due to a lack of

salivary secretion; the causes include

1. Sjögren syndrome: an autoimmune disorder,

that is usually also accompanied by involvement of

the lacrimal glands that produces dry eyes

(keratoconjunctivitis sicca).

2. Radiation therapy

Inflammation (Sialadenitis)

Sialadenitis refers to inflammation of a salivary

gland; it may be

1. Traumatic

2. Infectious: viral, bacterial

3. Autoimmune

The most common form of viral sialadenitis is

mumps, which usually affects the parotids. The

pancreas and testes may also be involved.

Bacterial sialadenitis is seen as a complication of

1. Stones obstructing ducts of a major salivary

gland (Sialolithiasis), particularly the

submandibular.

2. Dehydration with decreased secretory

function as is sometimes occurs in

a. patients on long-term phenothiazines that

suppress salivary secretion.

b. elderly patients with a recent major thoracic

or abdominal surgery.

Unilateral involvement of a single gland is the

rule and the inflammation may be

suppurative.

The inflammatory involvement causes painful

enlargement and sometimes a purulent ductal

discharge.

Sjögren syndrome causes an immunolgically

mediated sialadenitis i.e. inflammatory

damage of the salivary tissues.

NEOPLASMS OF SALIVARY GLANDS

Neoplasms of the salivary glands (benign and

malignant) are generally uncommon, constituting

less than 2% of human tumors. We will restrict our

discussion on the more common examples.

The relative frequency distributions of these tumors

in relation to various salivary glands are as follows

Parotid gland 80%

Submandibular gland 10%

Minor salivary and sublingual glands 10%

The incidence of malignant tumors within the

glands is, however, different from the above

Sublingual tumors 80%

Minor salivary glands 50%

Submandibular glands 40%

Parotid glands 25%

These tumors usually occur in adults, with a slight

female predominance. Excluded from this rule is

Warthin tumor, which occurs much more

frequently in males than in females. The benign

tumors occur most often around the age of 50 to

60 years; the malignant ones tend to appear in

older age groups. Neoplasms of the parotid

produce distinctive swellings in front of, or below

the ear. Clinically, there are no reliable criteria to

differentiate benign from the malignant tumors;

therefore, pathological evaluation is necessary.

Pleomorphic Adenomas (Mixed Salivary Gland

Tumors)

These benign tumors commonly occur within the

parotid gland (constitute 60% of all parotid tumors).

Gross features

Most tumors are rounded, encapsulated masses.

The cut surface is gray-white with myxoid and light

blue translucent areas of chondroid.

Microscopic features

The main constituents are a mixture of ductal

epithelial and myoepithelial cells, and it is believed

that all the other elements, including mesenchymal,

are derived from the above cells (hence the name

adenoma).

The epithelial/myoepithelial components of the

neoplasm are arranged as glands, strands, or sheets.

These various epithelial/myoepithelial elements are

dispersed within a background of loose myxoid tissue

that may contain islands of cartilage-like islands and,

rarely bone.

Sometimes, squamous differentiation is present.

In some instances, the tumor capsule is focally

deficient allowing the tumor to extend as tongue-like

protrusions into the surrounding normal tissue.

Enucleation of the tumor is, therefore, not advisable

because residual foci (the protrusions) may be left

behind and act as a potential source of multifocal

recurrences.

The incidence of malignant transformation increases

with the duration of the tumor.

Warthin Tumor is the second most common salivary

gland neoplasm. It is benign, arises usually in the

parotid gland and occurs more commonly in males

than in females. About 10% are multifocal and 10%

bilateral. Smokers have a higher risk than nonsmokers

for developing these tumors. Grossly, it is round to

oval, encapsulated mass & on section display gray

tissue with narrow cystic or cleft-like spaces filled with

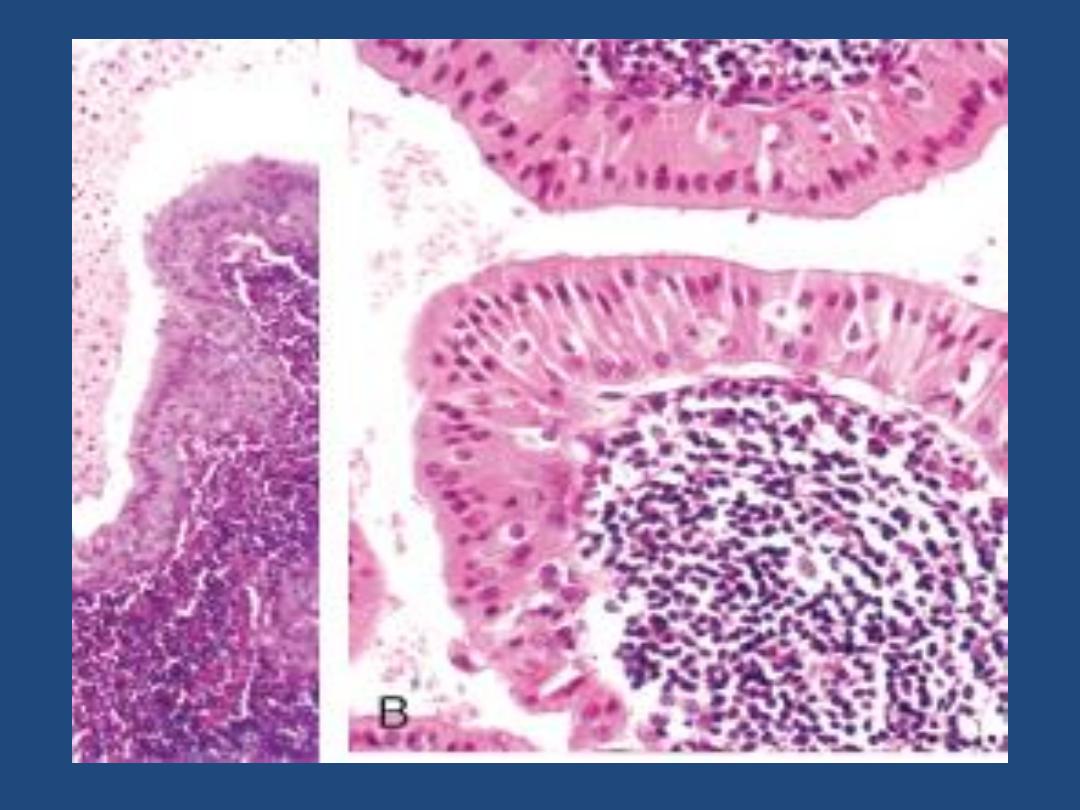

secretion. Microscopically, these spaces are lined by a

double layer of neoplastic epithelial cells resting on a

dense lymphoid stroma, sometimes with germinal

centers. This lympho-epithelial lining frequently project

into the spaces. The epithelial cells are oncoytes as

evidenced by their eosinophilic granular cytoplasm

(stuffed with mitochondria).

ESOPHAGUS

The main functions of the esophagus are to 1.

Conduct food and fluids from the pharynx to the

stomach 2. Prevent reflux of gastric contents into

the esophagus. These functions require motor

activity coordinated with swallowing, i.e. wave of

peristalsis, associated with relaxation of the LES in

anticipation of the peristaltic wave. This is followed

by closure of the LES after the swallowing reflex.

Maintenance of sphincter tone (positive pressure

relative to the rest of esophagus) is necessary to

prevent reflux of gastric contents.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Several congenital anomalies affect the esophagus

including the presence of ectopic gastric mucosa &

pancreatic tissues within the esophageal wall,

congenital cysts & congenital herniation of the

esophageal wall into the thorax. The latter is due to

impaired formation of the diaphragm. Atresia and

fistulas are uncommon but must be recognized &

corrected early because they cause immediate

regurgitation, suffocation & aspiration pneumontis

when feeding is attempted. In atresia, a segment of the

esophagus is represented by only a noncanalized cord,

with the upper pouch connected to the bronchus or

the trachea and a lower pouch leading to the stomach.

Webs, rings, and stenosis

Mucosal webs are shelf-like, eccentric protrusions of the

mucosa into the esophageal lumen. These are most common

in the upper esophagus. The triad of upper esophageal web,

iron-deficiency anemia, and glossitis is referred to as Plummer-

Vinson syndrome. This condition is associated with an

increased risk for postcricoid esophageal carcinoma.

Esophageal rings unlike webs are concentric plates of tissue

protruding into the lumen of the distal esophagus. Esophageal

webs and rings are encountered most frequently in women

over age 40. Episodic dysphagia is the main symptom.

Stenosis consists of fibrous thickening of the esophageal wall.

Although it may be congenital, it is more frequently the result

of severe esophageal injury with inflammatory scarring, as

from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), radiation,

scleroderma and caustic injury. Stenosis usually manifests as

progressive dysphagia, at first to solid foods but eventually to

fluids as well.

LESIONS ASSOCIATED WITH MOTOR DYSFUNCTION

Coordinated motor activity is important for proper

function of the esophagus. The major entities that

are caused by motor dysfunction of the esophagus

are

1. Achalasia

2. Hiatal hernia

3. Diverticula

4. Mallory-Weiss tear

Achalasia

Achalasia means "failure to relax." It is characterized by three

major abnormalities:

1. Aperistalsis (failure of peristalsis)

2. Increased resting tone of the LES

3. Icomplete relaxation of the LES in response to swallowing

In most instances, achalasia is an idiopathic disorder. In this

condition there is progressive dilation of the esophagus above

the persistently contracted LES. The wall of the esophagus

may be of normal thickness, thicker than normal owing to

hypertrophy of the muscular wall, or markedly thinned by

dilation (when dilatation overruns hypertrophy). The mucosa

just above the LES may show inflammation and ulceration.

Young adults are usually affected and present with progressive

dysphagia.

Complications of achalasia are

1. Aspiration pneumonitis of undigested food

2. Monilial esophagitis

3. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (about

5% of patients)

4. Lower esophageal diverticula

Hiatal Hernia

Hiatal hernia is characterized by separation of the

diaphragmatic crura leading to widening of the space around

the esophageal wall. Two types of hiatal hernia are

recognized:

1. The sliding type (95%)

2. The paraesophageal type

In the sliding hernia the stomach skates up through the patent

hiatus above the diaphragm creating a bell-shaped dilation. In

paraesophageal hernias, a separate portion of the stomach,

usually along the greater curvature, enters the thorax through

the widened foramen. The cause of hiatal hernia is unknown.

It is not clear whether it is a congenital malformation or is

acquired during life. Only about 10% of adults with a sliding

hernia suffer from heartburn or regurgitation of gastric juices

into the mouth. These are due to incompetence of the LES

and are accentuated by positions favoring reflux (bending

forward, lying supine) and obesity.

Complications of hiatal hernias include

1. Ulceration, bleeding and perforation (both

types)

2. Reflux esophagitis (frequent with sliding

hernias)

3. Strangulation of paraesophageal hernias

Diverticula

By definition a diverticulum is a "focal out pouching of

the alimentary tract wall that contains all or some of

its constituents"; they are divided into

1. False diverticulum is an out pouching of the mucosa

and submucosa through weak points in the muscular

wall.

2. True diverticulum consists of all the layers of the

wall and is thought to be due to motor dysfunction of

the esophagus. They may develop in three regions of

the esophagus

a. Zenker diverticulum, located immediately above the

UES

b. Traction diverticulum near the midpoint of the

esophagus

c. Epiphrenic diverticulum immediately above the LES.

Lacerations (Mallory-Weiss Syndrome)

These refer to longitudinal tears at the GEJ or

gastric cardia and are the consequence of severe

retching or vomiting. They are encountered most

commonly in alcoholics, since they are susceptible

to episodes of excessive vomiting, but have been

reported in persons with no history of vomiting or

alcoholism. During episodes of prolonged vomiting,

reflex relaxation of LES fails to occur. The refluxing

gastric contents suddenly overcome the contracted

musculature leading to forced, massive dilation of

the lower esophagus with tearing of the stretched

wall.

Pathological features

The linear irregular lacerations, which are usually

found astride the GEJ or in the gastric cardia, are

oriented along the axis of the esophageal lumen.

The tears may involve only the mucosa or may

penetrate deeply to perforate the wall.

Infection of the mucosal defect may lead to

inflammatory ulcer or to mediastinitis. Usually the

bleeding is not profuse and stops without surgical

intervention. Healing is the usual outcome. Rarely

esophageal rupture occurs.

Esophageal Varices

Portal hypertension when sufficiently prolonged or

severe induces the formation of collateral bypass veins

wherever the portal and caval venous systems

communicate. Esophageal varices refer to the

prominent plexus of deep mucosal and submucosal

venous collaterals of the lower esophagus subsequent

to the diversion of portal blood through them through

the coronary veins of the stomach. From the varices

the blood is diverted into the azygos veins, and

eventually into the systemic veins. Varices develop in

90% of cirrhotic patients. Worldwide, after alcoholic

cirrhosis, hepatic schistosomiasis is the second most

common cause of variceal bleeding.

Pathological features

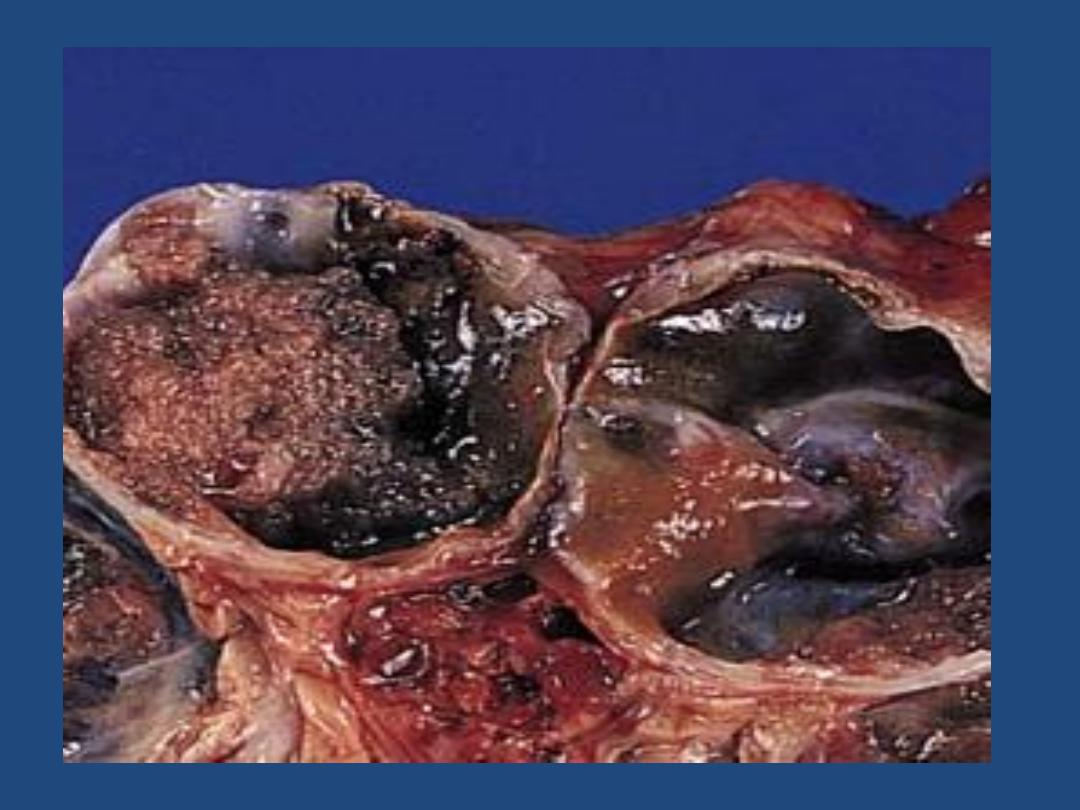

The increased pressure in the esophageal plexus produces

dilated tortuous vessels that are liable to rupture.

Varices appear as tortuous dilated veins lying primarily

within the submucosa of the distal esophagus and proximal

stomach.

The net effect is irregular protrusion of the overlying

mucosa into the lumen. The mucosa is often eroded because

of its exposed position.

Variceal rupture produces massive hemorrhage into the

lumen. In this instance, the overlying mucosa appears

ulcerated and necrotic.

Rupture of esophageal varices usually produces massive

hematemesis. Among patients with advanced liver cirrhosis,

such a rupture is responsible for 50% of the deaths. Some

patients die as a direct consequence of the hemorrhage

(hypovolemic shock); others of hepatic coma triggered by the

hemorrhage.

Esophagitis

This term refers to inflammation of the esophageal

mucosa. It may be caused by a variety of physical,

chemical, or biologic agents. Reflux Esophagitis

(Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease or GERD) is the

most important cause of esophagitis and signifies

esophagitis associated with reflux of gastric

contents into the lower esophagus. Many causative

factors are involved, the most important is

decreased efficacy of esophageal antireflux

mechanisms, particularly LES tone. In most

instances, no cause is identified. However, the

following may be contributatory

a. Central nervous system depressants including

alcohol

b. Smoking

c. Pregnancy

d. Nasogastric tube

e. Sliding hiatal hernia

f. hypothyroidism

g. Systemic sclerosis

Any one of the above mechanism may be the

primary cause in an individual case, but more than

one is likely to be involved in most instances. The

action of gastric juices is vital to the development of

esophageal mucosal injury.

Gross (endoscopic) features

These depend on the causative agent and on the

duration and severity of the exposure.

Mild esophagitis may appear grossly as simple

hyperemia. In contrast, the mucosa in severe

esophagitis shows confluent erosions or total

ulceration into the submucosa.

Microscopic features

Three histologic features are characteristic:

1. Inflammatory cells including eosinophils within the

squamous mucosa.

2. Basal cells hyperplasia

3. Extension of lamina propria papillae into the upper

third of the mucosa.

The disease mostly affects those over the age of 40

years. The clinical manifestations consist of

dysphagia, heartburn, regurgitation of a sour fluid

into the mouth, hematemesis, or melena. Rarely,

there are episodes of severe chest pain that may be

mistaken for a "heart attack.“

The potential consequences of severe reflux

esophagitis are

1. Bleeding

2. Ulceration

3. Stricture formation

4. Tendency to develop Barrett esophagus

Barrett Esophagus (BE)

10% of patients with long-standing GERD develop this

complication. BE is the single most important risk factor for

esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE refers to columnar

metaplasia of the distal squamous mucosa; this occurs in

response to prolonged injury induced by refluxing gastric

contents. Two criteria are required for the diagnosis of Barrett

esophagus:

1. Endoscopic evidence of columnar lining above the GEJ

2. Histologic confirmation of the above in biopsy specimens.

The pathogenesis of Barrett esophagus appears to be due to a

change in the differentiation program of stem cells of the

esophageal mucosa. Since the most frequent metaplastic

change is the presence of columnar cells admixed with goblet

cells, the term "intestinal metaplasia" is used to describe the

histological alteration.

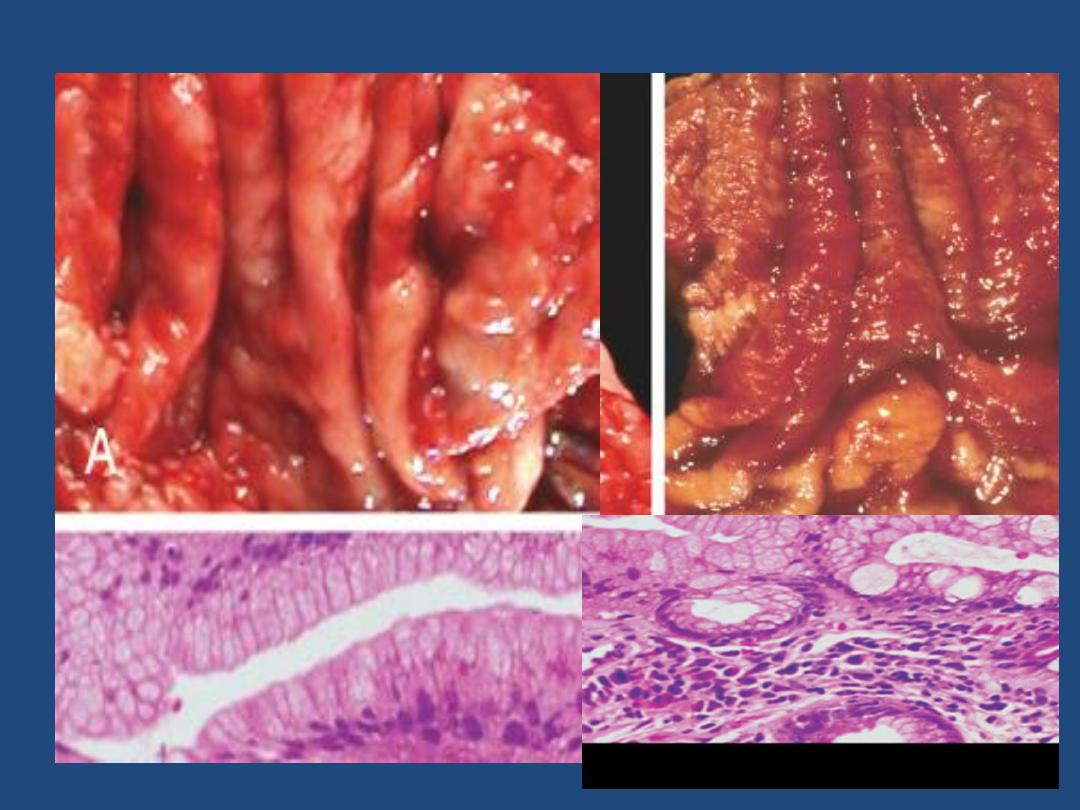

Gross features

Barrett esophagus is recognized as a red, velvety

mucosa located between the smooth, pale pink

esophageal squamous mucosa and the light brown

gastric mucosa.

It is displayed as tongues, patches or broad

circumferential bands replacing the

squamocolumnar junction several centimeters.

Microscopic features

the esophageal squamous epithelium is replaced by

metaplastic columnar epithelium, including interspersed

goblet cells, & may show a villous pattern (as that of the small

intestine hence the term intestinal metaplasia).

Critical to the pathologic evaluation of patients with Barrett

mucosa is the search for dysplasia within the metaplastic

epithelium. This dysplastic change is the presumed precursor

of malignancy (adenocarcinoma). Dysplasia is recognized by

the presence of cytologic and architectural abnormalities in

the columnar epithelium, consisting of enlarged, crowded,

and stratified hyperchromatic nuclei with loss of intervening

stroma between adjacent glandular structures. Depending on

the severity of the changes, dysplasia is classified as low-

grade or high-grade.

Approximately 50% of patients with high-grade

dysplasia may already have adjacent

adenocarcinoma.

Most patients with the first diagnosis of Barrett

esophagus are between 40 and 60 years. Barrett

esophagus is clinically significant due to

1. The secondary complications of local peptic

ulceration with bleeding and stricture.

2. The development of adenocarcinoma, which in

patients with long segment disease (over 3 cm of

Barrett mucosa), occurs at a frequency that is 30- to

40 times greater than that of the general

population.

Other causes of esophagitis

In addition to GERD (which is, in fact, a chemical

injury), esophageal inflammation may have many

origins. Examples include ingestion of mucosal

irritants (such as alcohol, corrosive acids or alkalis as

in suicide attempts), cytotoxic anticancer therapy,

bacteremia or viremia (in immunosuppressed

patients), fungal infection (in debilitated or

immunosuppressed patients or during broad-

spectrum antimicrobial therapy; candidiasis by far

the most common), and uremia.

TUMORS

Benign Tumors

Leiomyomas are the most common benign tumors

of the esophagus.

Malignant Tumors

Carcinomas of the esophagus (5% of all cancers of

the GIT) have, generally, a poor prognosis because

they are often discovered too late. Worldwide,

squamous cell carcinomas constitute 90% of

esophageal cancers, followed by adenocarcinoma.

Other tumors are rare.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

Most SCCs occur in adults over the age of 50. The

disease is more common in males than females.

The regions with high incidence include Iran &

China. Blacks throughout the world are at higher

risk than are whites.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Factors Associated with the Development of

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus are

classified as

1. Dietary

Deficiency of vitamins (A, C, riboflavin, thiamine,

and pyridoxine) & trace elements (zinc)

Fungal contamination of foodstuffs

High content of nitrites/nitrosamines

Betel chewing (betel: the leaf of a climbing

evergreen shrub, of the pepper family, which is

chewed in the East with a little lime.)

2. Lifestyle

Burning-hot food

Alcohol consumption

Tobacco abuse

3. Esophageal Disorders

Long-standing esophagitis

Achalasia

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

4. Genetic Predisposition

Long-standing celiac disease

Racial disposition

The marked geographical variations in the incidence

of the disease strongly implicate dietary and

environmental factors, with a contribution from

genetic predisposition. The majority of cancers in

Europe and the United States are attributable to

alcohol and tobacco. Some alcoholic drinks contain

significant amounts of such carcinogens as

polycyclic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, and other

mutagenic compounds. Nutritional deficiencies

associated with alcoholism may contribute to the

process of carcinogenesis.

Human papillomavirus DNA is found frequently in

esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from high-

incidence regions.

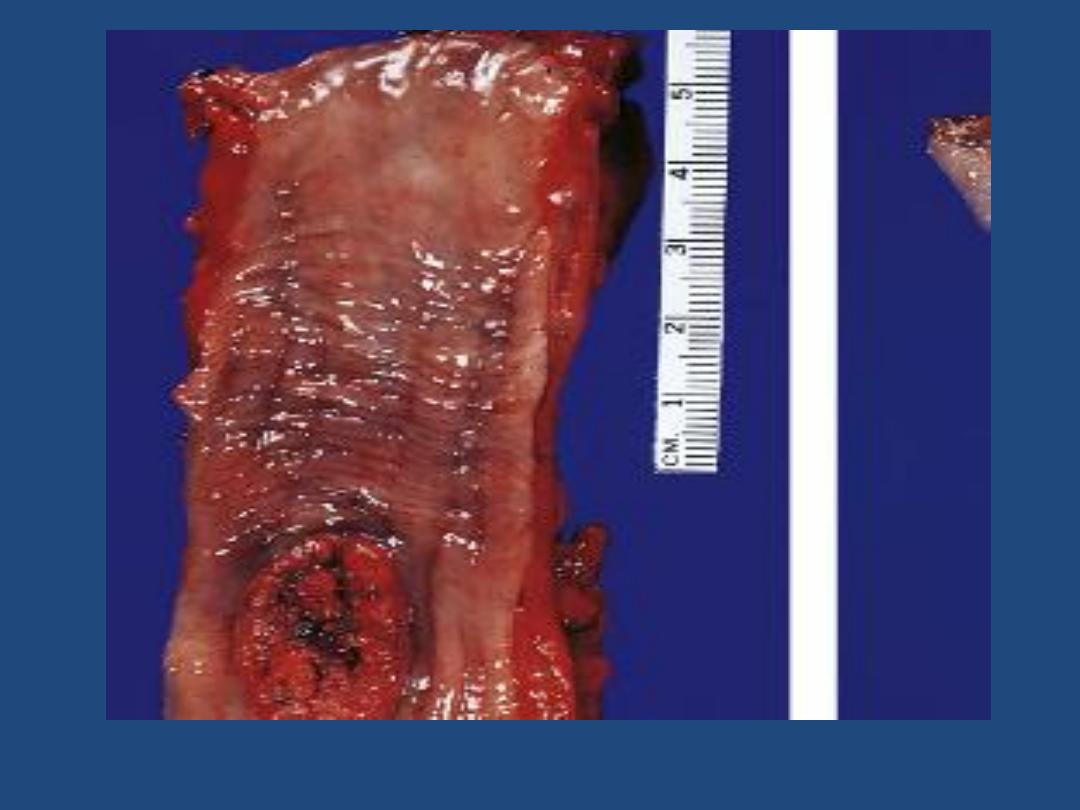

Gross features

Like squamous cell carcinomas arising in other locations,

those of the esophagus begin as in situ lesions.

When they become overt, about 20% of these tumors are

located in the upper third, 50% in the middle third, and 30%

in the lower third of the esophagus.

Early lesions appear as small, gray-white, plaque-like

thickenings of the mucosa but with progression, three gross

patterns are encountered:

1. Fungating (polypoid) (60%) that protrudes into the lumen

2. Flat (diffusely infiltrative) (15%) that tends to spread within

the wall of the esophagus, causing thickening, rigidity, and

narrowing of the lumen

3. Excavated (ulcerated) (25%) that digs deeply into

surrounding structures and may erode into the respiratory

tree (with resultant fistula and pneumonia) or aorta (with

catastrophic bleeding) or may permeate the mediastinum and

pericardium.

Local extension into adjacent mediastinal structures

occurs early, possibly due to the absence of serosa

for most of the esophagus. Tumors located in the

upper third of the esophagus also metastasize to

cervical lymph nodes; those in the middle third to

the mediastinal, paratracheal, and tracheobronchial

lymph nodes; and those in the lower third most

often spread to the gastric and celiac groups of

nodes.

Microscopic features

Most squamous cell carcinomas are moderately to well-

differentiated,

They are invasive tumors that have infiltrated through the wall or

beyond.

The rich lymphatic network in the submucosa promotes extensive

circumferential and longitudinal spread.

Esophageal carcinomas are usually quite large by the time of

diagnosis, produces dysphagia and obstruction gradually. Cachexia

is frequent. Hemorrhage and sepsis may accompany ulceration of

the tumor.

The five-year survival rate in patients with superficial esophageal

carcinoma is about 75%, compared to 25% in patients who

undergo "curative" surgery for more advanced disease. Local

recurrence and distant metastasis following surgery are common.

The presence of lymph node metastases at the time of resection

significantly reduces survival.

Adenocarcinoma

With increasing recognition of Barrett mucosa,

most adenocarcinomas in the lower third of the

esophagus arise from the Barrett mucosa.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

These focus on Barrett esophagus. The lifetime risk

for cancer development from Barrett esophagus is

approximately 10%. Tobacco exposure and obesity

are risk factors. Helicobacter pylori infection may be

a contributing factor.

Gross features:

adenocarcinomas arising in the setting of Barrett

esophagus are usually located in the distal

esophagus and may invade the adjacent gastric

cardia.

As is the case with squamous cell carcinomas,

adenocarcinomas initially appear as flat raised

patches that may develop into large nodular

fungating masses or may exhibit diffusely infiltrative

or deeply ulcerative features.

Microscopic features

Most tumors are mucin-producing glandular

tumors exhibiting intestinal-type features.

Multiple foci of dysplastic mucosa are frequently

present adjacent to the tumor.

Adenocarcinomas arising in Barrett esophagus

chiefly occur in patients over the age of 40 years

and similar to Barrett esophagus, it is more common

in men than in women, and in whites more than

blacks (in contrast to squamous cell carcinomas).

As in other forms of esophageal carcinoma, patients

usually present because of difficulty swallowing,

progressive weight loss, bleeding, and chest pain.

The prognosis is as poor as that for other forms of

esophageal cancer, with under 20% overall five-year

survival. Identification and resection of early

cancers with invasion limited to the mucosa or

submucosa improves five-year survival to over 80%.

Regression or surgical removal of Barrett esophagus

has not yet been shown to eliminate the risk for

adenocarcinoma.