1

PROF.DR.MAHA SHAKIR (Lec.1)

Hemodynamic Disorders ,

Thromboembolism, and Shock

The health of cells and tissues depends on the circulation of blood,

which delivers oxygen and nutrients and removes wastes generated

by cellular metabolism.

In this system we will discuss the following:

• Hyperemia and Congestion

• Hemorrhage

• Edema

• Thrombosis

• Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

• Embolism

• Infarction

• Shock

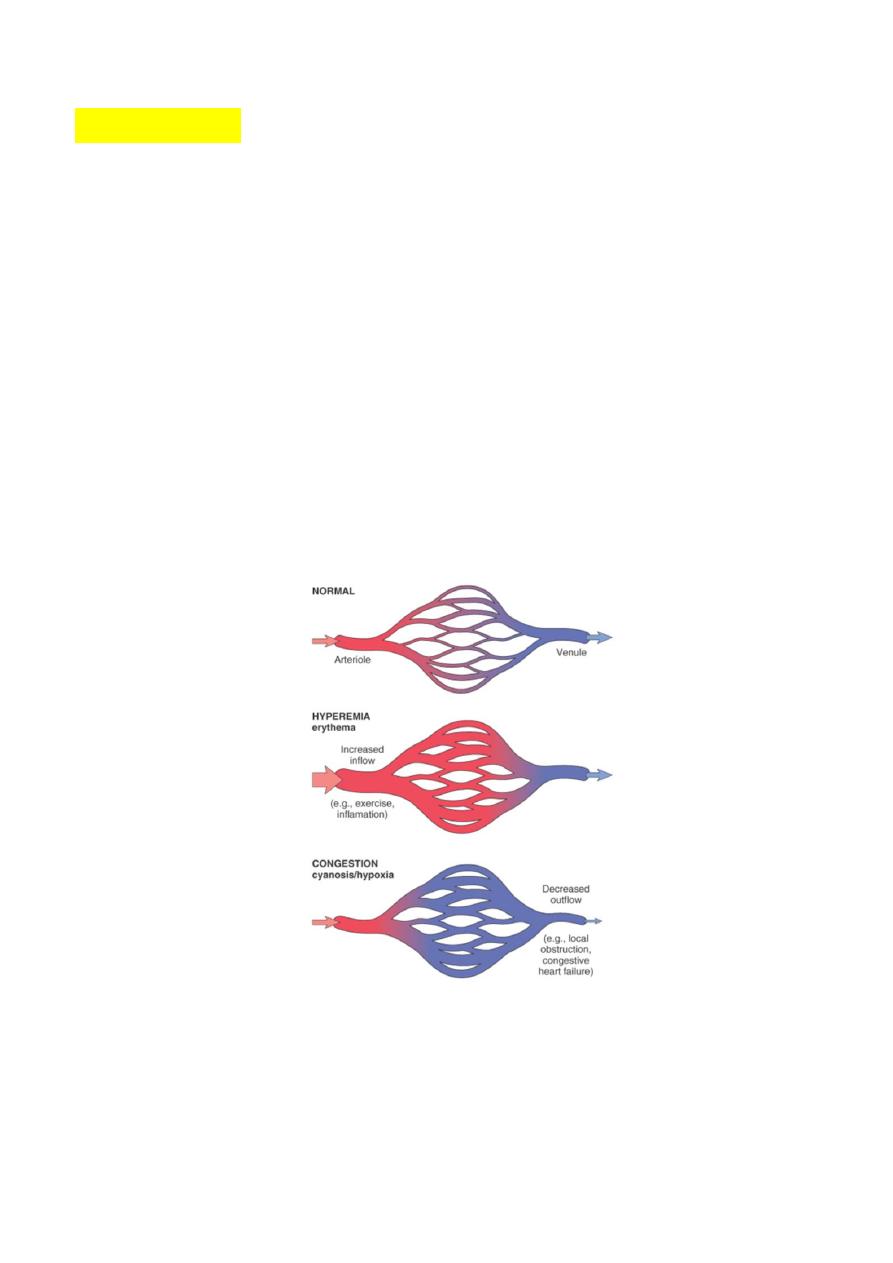

Hypermia and Congestion

Definition:

Both of them can be defined as a local increase in volume of

blood in a particular tissue.

Hypermia

It is an active process resulting from arteriolar dilation and increased

blood inflow, as occurs at sites of:

• exercising skeletal muscle

• or acute inflammation

Hyperemic tissues are redder than normal because of

engorgement with oxygenated blood.

2

Congestion

Congestion

is a passive process resulting from impaired outflow of

venous blood from a tissue. It can occur:

• systemically, as in cardiac failure,

• or locally as a consequence of an isolated venous obstruction.

Congested tissues have an abnormal blue-red color

(

cyanosis

) that stems from the accumulation of deoxygenated

hemoglobin in the affected area.

In long-standing chronic congestion

,

inadequate tissue perfusion

and persistent hypoxia may lead to

:

• parenchymal

cell death.

• secondary tissue

fibrosis

.

• the elevated intravascular pressures may cause

edema

or

sometimes rupture capillaries forming focal

hemorrhage.

Fig.HYPEREMIA/(CONGESTION)

3

MORPHOLOGY

Cut surfaces of hyperemic or congested tissues feel wet and

typically ooze blood.

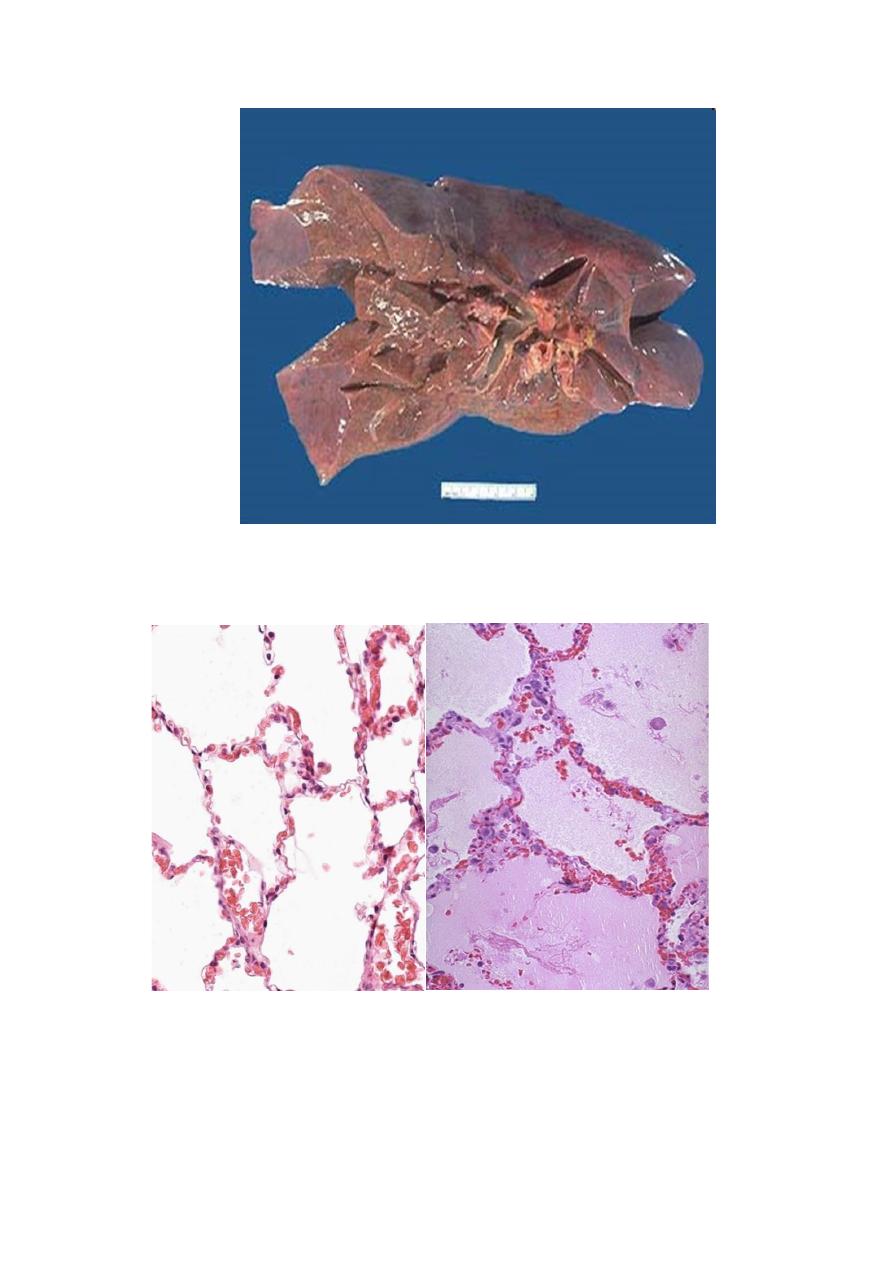

a) Pulmonary congestion

1- Acute pulmonary congestion:

• Alveolar capillaries engorged with blood

• variable degrees of alveolar septal edema and intraalveolar

hemorrhage.

-

2 Chronic pulmonary congestion

• Thickened & fibrotic septa

• Alveolar spaces contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages (“heart

failure cells”) derived from phagocytosed red cells.

Fig; Lung, acute pulmonary congestion.

4

fig:Lung, chronic passive congestions: surface The lung has a red-brown color

due to accumulation of hemosiderin from extravasated erythrocytes. Fibrosis causes

the cut edges to stand up rather

than collapse.

Fig: left :normal lung. Right:ACUTE PASSIVE HYPEREMIA/CONGESTION, LUNG

5

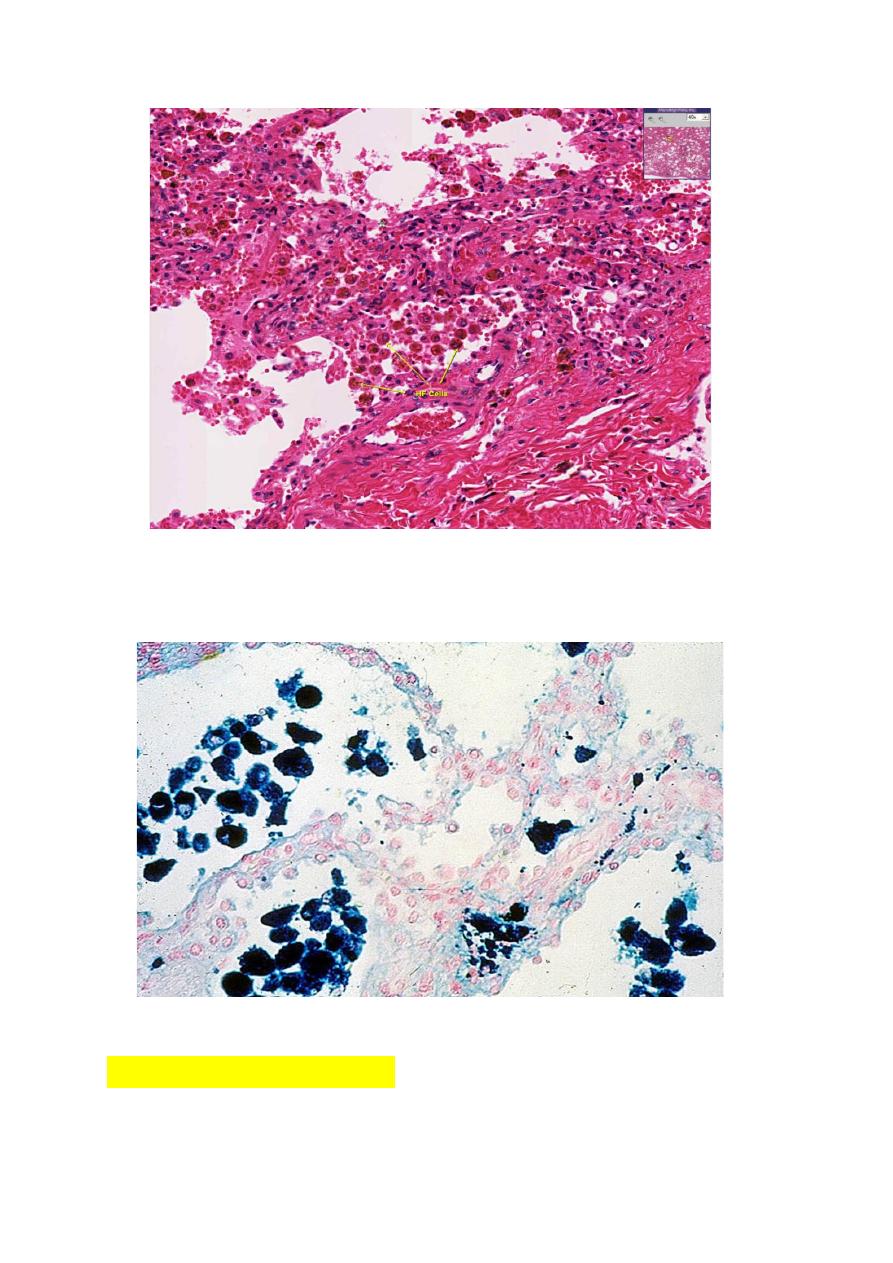

Fig:CHRONIC PASSIVE HYPEREMIA/CONGESTION, LUNG: heart failure cells

Fig:Special stain for haemosiderin (prusian blue) for heart failure cells

b) Hepatic congestion

1-Acute hepatic congestion:

6

• the central vein and sinusoids are distended with blood,

• and there may even be necrosis of centrally located hepatocytes.

• The periportal hepatocytes, better oxygenated,???

because of their proximity to hepatic arterioles, experience

less severe hypoxia and may develop only reversible fatty change.

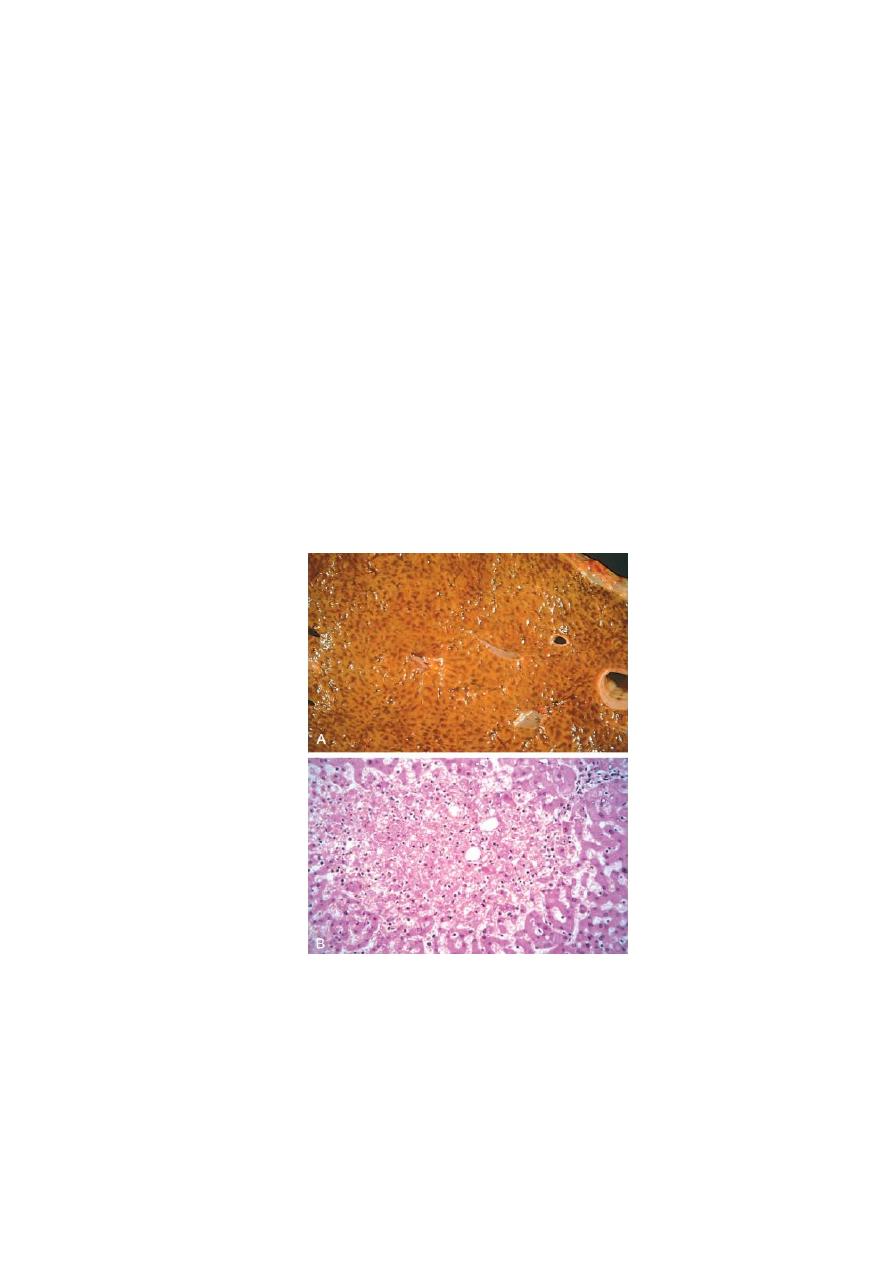

2-Chronic passive congestion of liver:

Gross examination

the central regions of the hepatic lobules, viewed, are

red-brown and slightly depressed (owing to cell loss) and are accentuated

against the surrounding zones of uncongested tan, sometimes fatty, liver

(nutmeg liver)

Microscopic findings

include centrilobular hepatocyte necrosis, hemorrhage,

and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

Fig. Liver with chronic passive congestion and hemorrhagic necrosis.(A) In this autopsy

specimen, central areas are red and slightly depressed compared with the surrounding

tan viable parenchyma, creating “nutmeg liver” (so called because it resembles the cut

surface of a nutmeg). (B) Microscopic preparation shows centrilobular hepatic necrosis

with hemorrhage and scattered inflammatory cells.

7

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage, defined as the extravasation of blood from

vessels, is most often the result of damage to blood vessels

or defective clot formation.

• capillary bleeding can occur in chronically congested tissues.

Trauma, atherosclerosis, or inflammatory or neoplastic erosion

of a vessel wall also may lead to hemorrhage, which may be

extensive if the affected vessel is a large vein or artery.

• The risk of hemorrhage is increased in a wide variety of clinical

disorders collectively called

hemorrhagic diatheses.

These have

diverse causes, including inherited or acquired defects in

vessel

walls, platelets, or coagulation factors,

all of which must function

properly to ensure homeostasis.

Hemorrhage may be manifested by different appearances

and clinical consequences.

Hemorrhage may be external or accumulate within a tissue as a

hematoma

, which ranges in significance from trivial to fatal. Large

bleeds into body cavities are described variously according to

location—

hemothorax

,

hemopericardium

,

hemoperitoneum

,

or

hemarthrosis

(in joints).

Petechiae

are minute (1 to 2 mm in diameter) hemorrhages into skin,

mucous membranes, or serosal surfaces ; causes include low platelet

counts (thrombocytopenia), defective platelet function, and loss of

vascular wall support, as in vitamin C deficiency.

Purpura

are slightly larger (3 to 5 mm) hemorrhages.

Purpura can result from the same disorders that cause petechiae, as

well as trauma, vascular inflammation (vasculitis), and increased

vascular fragility.

Ecchymoses

are larger (1 to 2 cm) subcutaneous hematomas

(colloquially called bruises).

• Extravasated red cells are phagocytosed and degraded by

macrophages; the characteristic color changes of a bruise result

8

from the enzymatic conversion of

hemoglobin

(red-blue color) to

bilirubin

(blue-green color) and eventually

hemosiderin

(golden-

brown).

The clinical significance of any particular hemorrhage

depends on:

• the volume of blood that is lost

•

and the rate of bleeding.

Rapid loss of up to 20% of the blood

volume, or slow losses of even larger amounts, may have little

impact in healthy adults; greater losses, however, can cause

hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock

•

The site of hemorrhage

also is important; bleeding that would

be trivial in the subcutaneous tissues can cause death if located

in the brain .

❖

chronic or recurrent external blood loss (e.g., due to

peptic ulcer or menstrual bleeding) frequently culminates

in iron deficiency anemia as a consequence of a loss of

iron in hemoglobin.

❖

By contrast, iron is efficiently recycled from phagocytosed

red cells, so internal bleeding (e.g., a hematoma) does not

lead to iron deficiency.

9

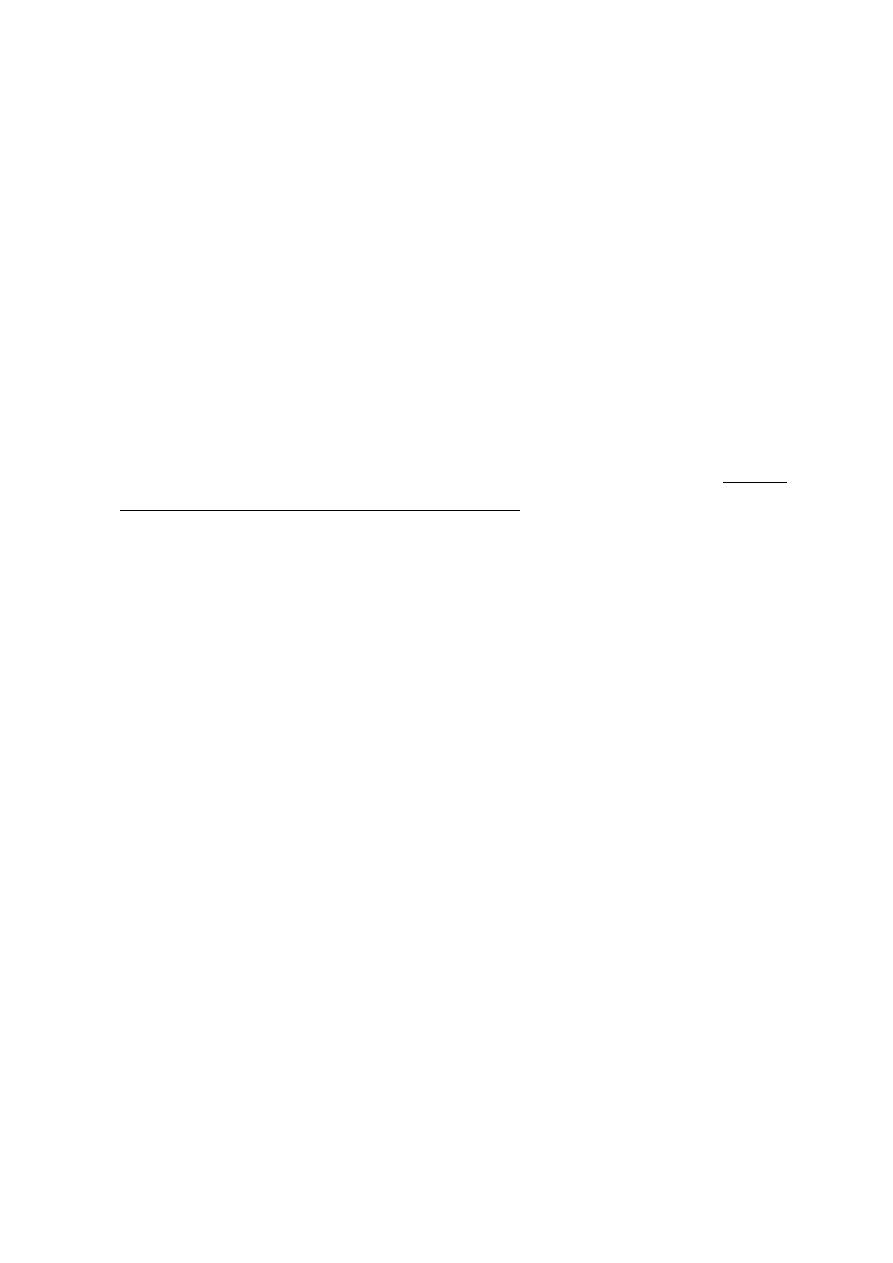

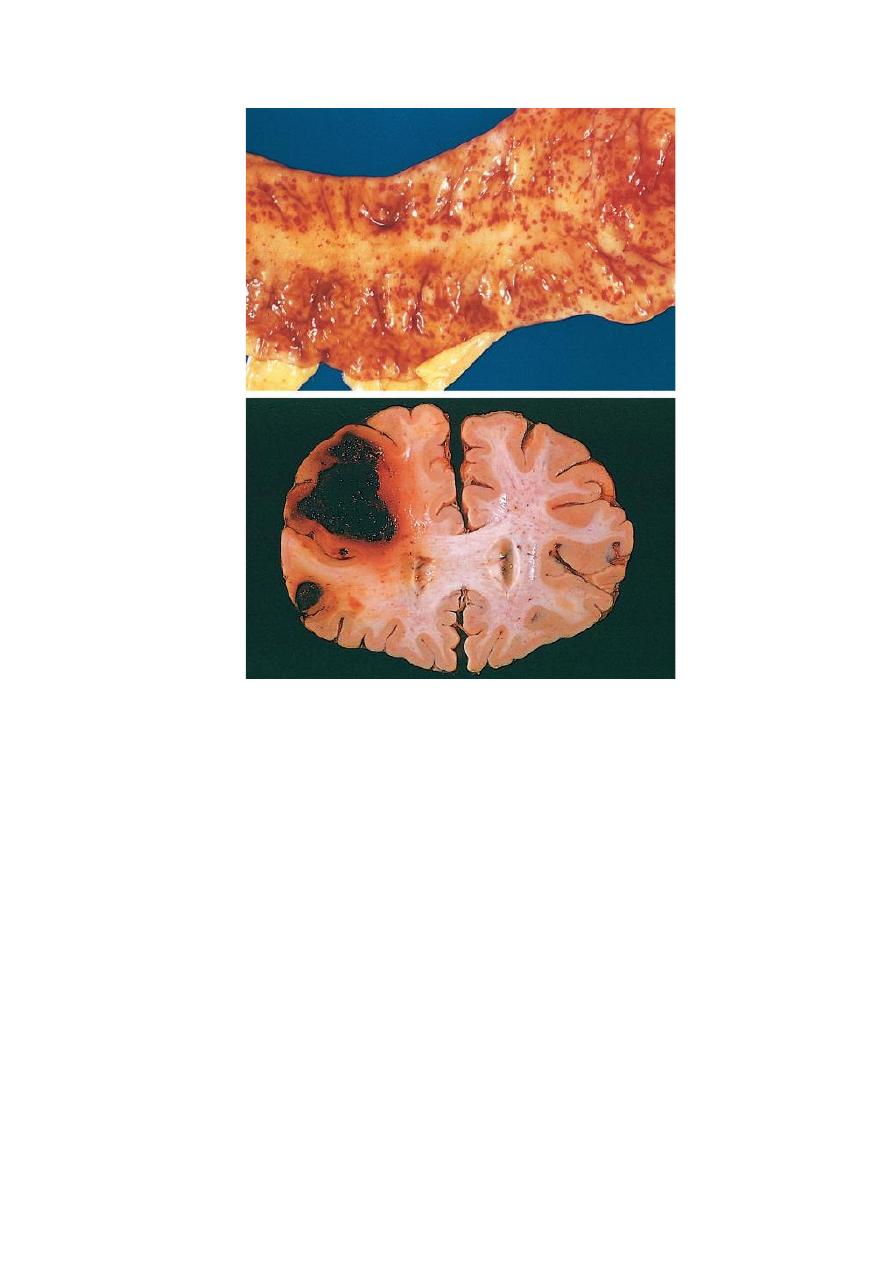

Fig.

(A) Punctate petechial hemorrhages of the colonic mucosa, a consequence

of thrombocytopenia. (B) Fatal intracerebral hemorrhage.