201

FORMATION OF THE LUNG BUDS

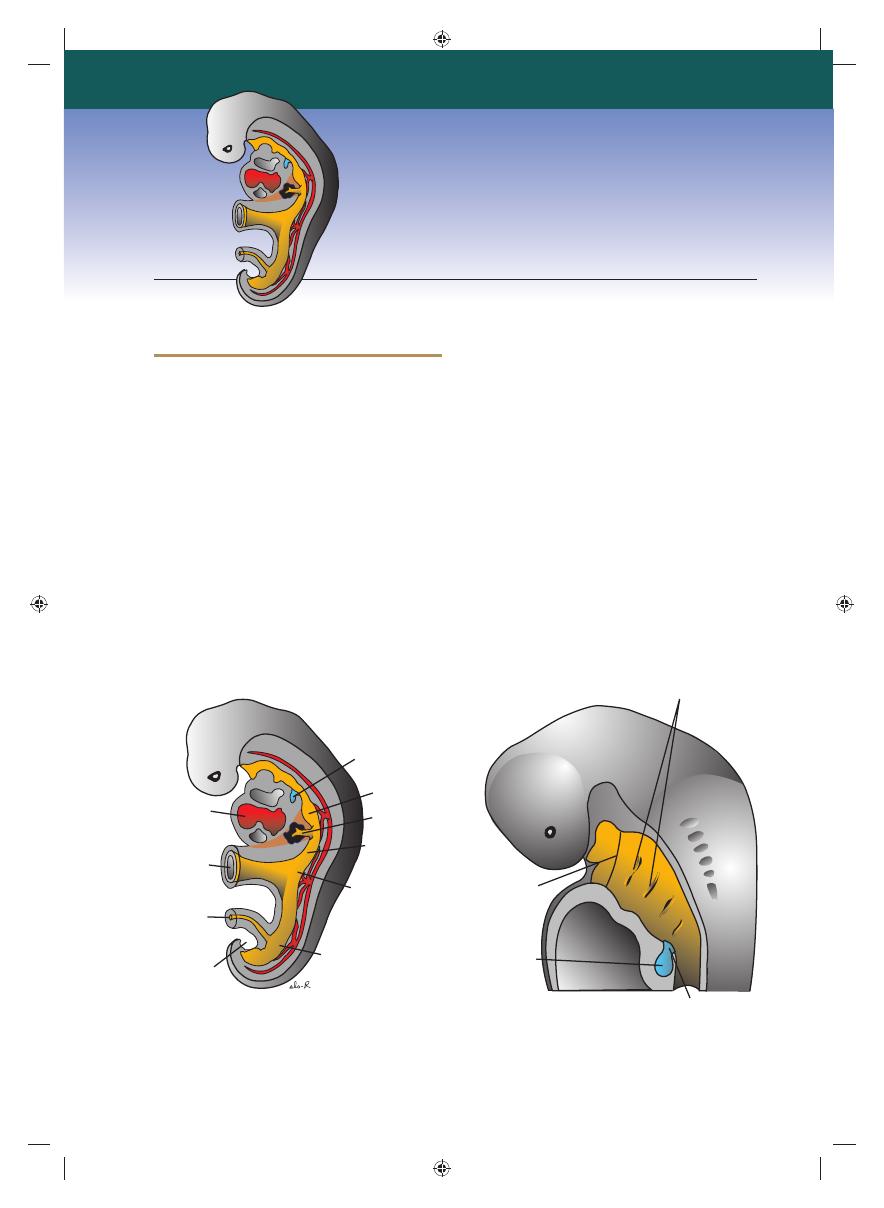

When the embryo is approximately 4 weeks old,

the respiratory diverticulum (lung bud)

appears as an outgrowth from the ventral wall

of the foregut (Fig. 14.1A). The appearance and

location of the lung bud are dependent upon an

increase in retinoic acid (RA) produced by

adjacent mesoderm. This increase in RA causes

upregulation of the transcription factor TBX4

expressed in the endoderm of the gut tube at

the site of the respiratory diverticulum. TBX4

induces formation of the bud and the continued

growth and differentiation of the lungs. Hence,

epithelium

of the internal lining of the lar-

ynx, trachea, and bronchi, as well as that of the

lungs, is entirely of endodermal origin. The

cartilaginous, muscular

, and connective tis-

sue

components of the trachea and lungs are

derived from splanchnic mesoderm surround-

ing the foregut.

Initially, the lung bud is in open commu-

nication with the foregut (Fig. 14.1B). When

the diverticulum expands caudally, however,

two longitudinal ridges, the tracheoesoph-

ageal ridges

, separate it from the foregut

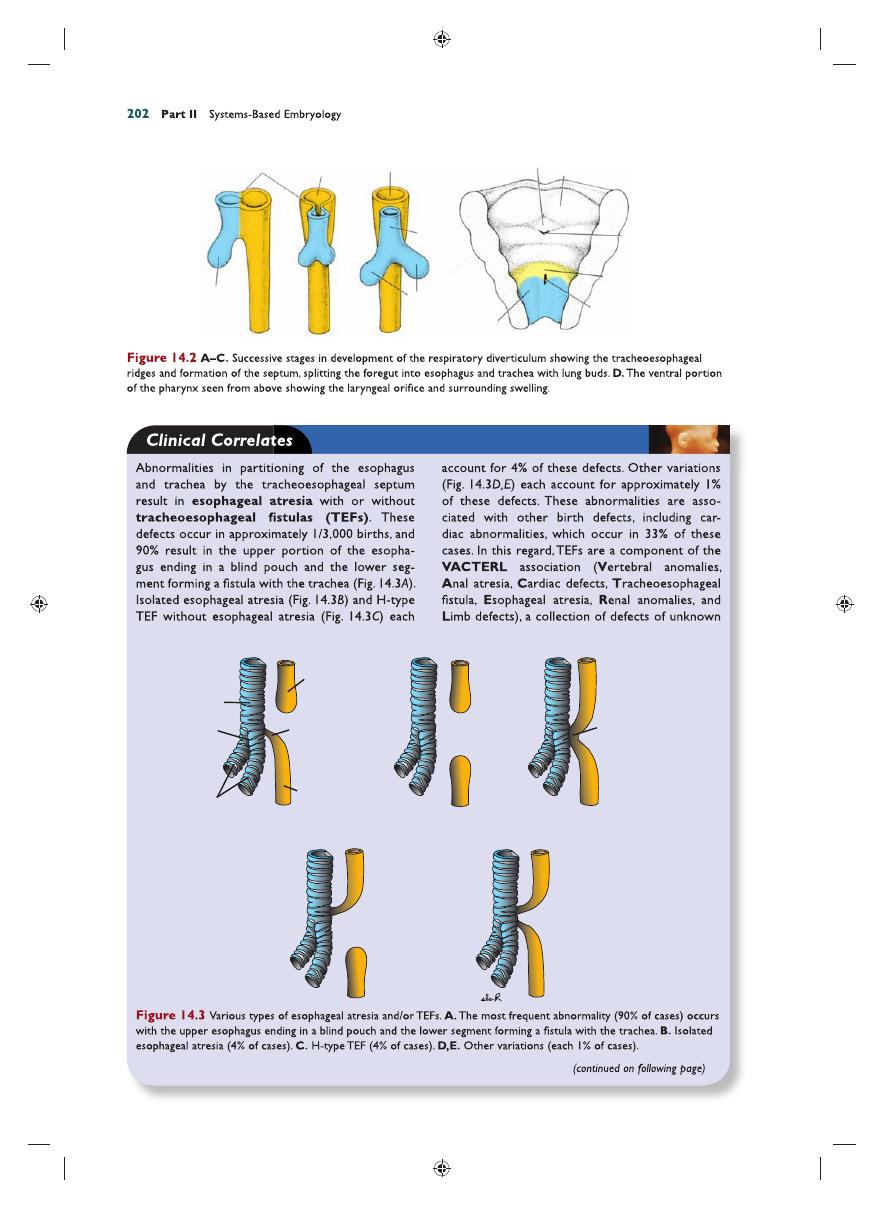

(Fig. 14.2A). Subsequently, when these ridges

fuse to form the tracheoesophageal septum,

the foregut is divided into a dorsal portion, the

esophagus

, and a ventral portion, the trachea

and lung buds (Fig. 14.2B,C). The respiratory

primordium maintains its communication with

the pharynx through the laryngeal orifi ce

(Fig. 14.2D).

Chapter

14

Respiratory System

Openings of

pharyngeal pouches

Laryngotracheal

orifice

Respiratory

diverticulum

Respiratory

diverticulum

Heart

Vitelline

duct

Allantois

Cloacal

membrane

A

B

Attachment of

buccopharyngeal

membrane

Hindgut

Liver bud

Duodenum

Midgut

Stomach

Figure 14.1

A. Embryo of approximately 25 days’ gestation showing the relation of the respiratory diverticulum to the

heart, stomach, and liver. B. Sagittal section through the cephalic end of a 5-week embryo showing the openings of the

pharyngeal pouches and the laryngotracheal orifi ce.

Sadler_Chap14.indd 201

Sadler_Chap14.indd 201

8/26/2011 4:17:37 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:37 AM

Lateral lingual swelling

Respiratory

diverticulum

Foramen

cecum

Tuberculum impar

Lung

buds

Trachea

Esophagus

Tracheoesophageal

ridge

Foregut

Epiglottal

swelling

Laryngeal

orifice

I

I

II

II

IV

A

C

B

VI

Laryngeal

swellings

D

A

E

B

D

C

Trachea

Bifurcation

Bronchi

Tracheoesophageal

fistula

Distal part of

esophagus

Proximal blind-

end part of

esophagus

Communication

of esophagus

with trachea

Sadler_Chap14.indd 202

Sadler_Chap14.indd 202

8/26/2011 4:17:37 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:37 AM

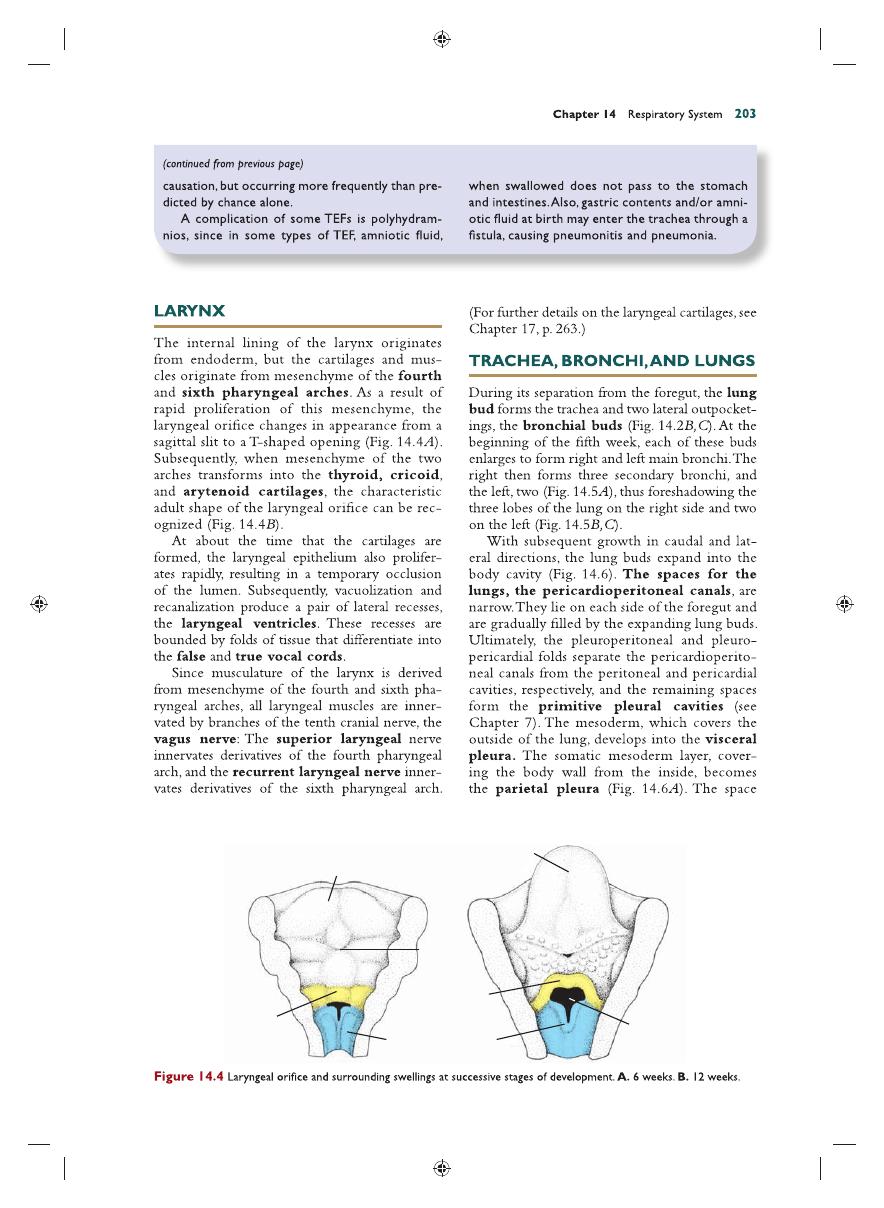

Lingual swelling

Body of tongue

Foramen

cecum

Epiglottis

Epiglottal

swelling

Arytenoid swellings

Laryngeal

orifice

l

ll

lll

lV

Vl

B

A

Sadler_Chap14.indd 203

Sadler_Chap14.indd 203

8/26/2011 4:17:40 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:40 AM

204

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

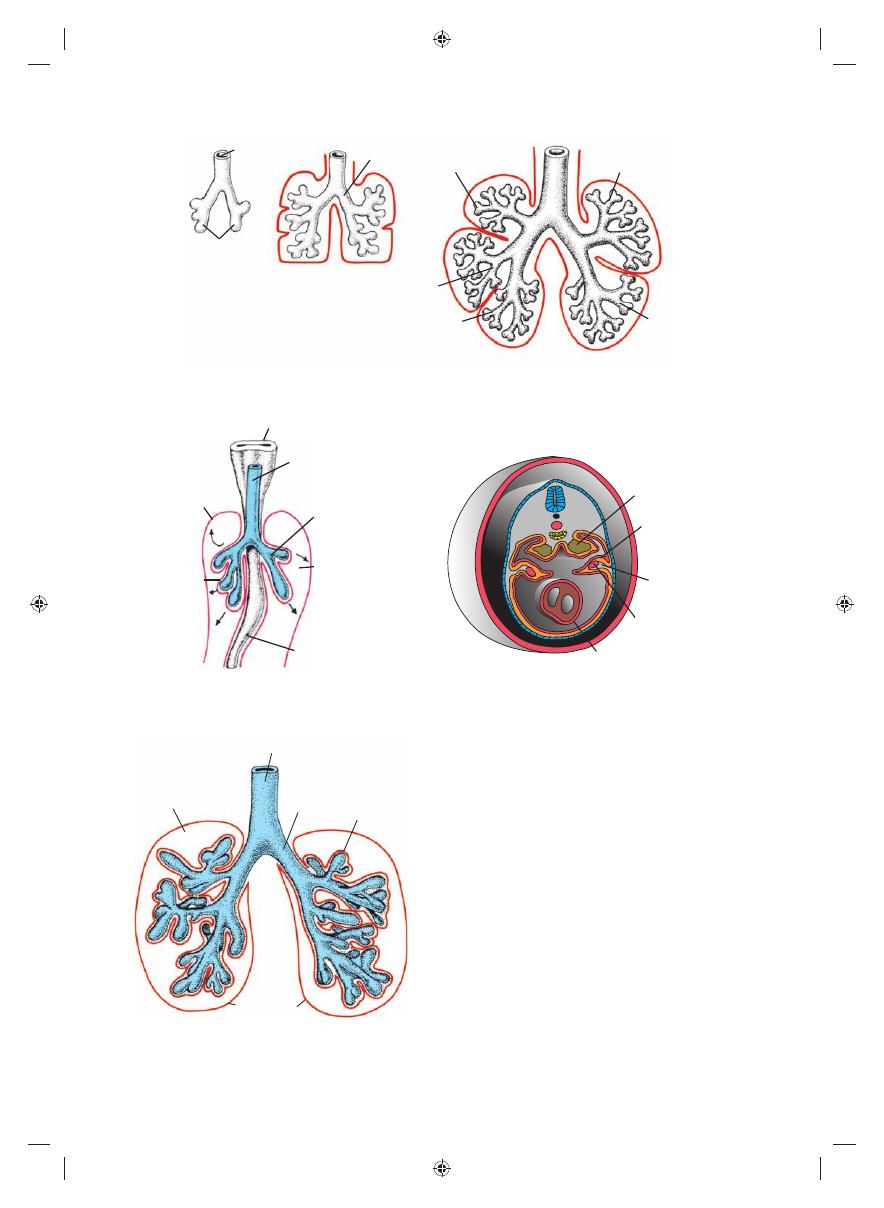

between the parietal and visceral pleura is the

pleural cavity

(Fig. 14.7).

During further development, secondary

bronchi divide repeatedly in a dichotomous

fashion, forming 10 tertiary (segmental)

bronchi in the right lung and 8 in the left, cre-

ating the bronchopulmonary segments of

the adult lung. By the end of the sixth month,

approximately 17 generations of subdivisions

have formed. Before the bronchial tree reaches

its fi nal shape, however, an additional six divi-

sions form during postnatal life

. Branching

is regulated by epithelial-mesenchymal inter-

actions between the endoderm of the lung

buds and splanchnic mesoderm that surrounds

them. Signals for branching, which emit from

the mesoderm, involve members of the fi bro-

blast growth factor family. While all of these

new subdivisions are occurring and the bron-

chial tree is developing, the lungs assume a more

caudal position, so that by the time of birth, the

Lung

buds

Left bronchus

Right upper lobe

Left upper

lobe

Left

lower

lobe

Right

middle lobe

Right lower lobe

A

B

C

Trachea

Figure 14.5

Stages in development of the trachea and lungs. A. 5 weeks. B. 6 weeks. C. 8 weeks.

Lung bud

Pleuro-

pericardial

fold

Phrenic

nerve

Common

cardinal

vein

Heart

B

Pharynx

Trachea

Parietal

pleura

Visceral

pleura

Lung bud

Pericardioperitoneal

canal

Visceral peritoneum

A

Figure 14.6

Expansion of the lung buds into the pericardioperitoneal canals. At this stage, the canals are in communication

with the peritoneal and pericardial cavities. A. Ventral view of lung buds. B. Transverse section through the lung buds showing

the pleuropericardial folds that will divide the thoracic portion of the body cavity into the pleural and pericardial cavities.

Trachea

Bronchus Visceral

pleura

Pleural cavity

Parietal pleura

Figure 14.7

Once the pericardioperitoneal canals sepa-

rate from the pericardial and peritoneal cavities, respec-

tively, the lungs expand in the pleural cavities. Note the

visceral and parietal pleura and defi nitive pleural cavity. The

visceral pleura extends between the lobes of the lungs.

Sadler_Chap14.indd 204

Sadler_Chap14.indd 204

8/26/2011 4:17:41 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:41 AM

Chapter 14 Respiratory System

205

Respiratory

bronchiole

Lung

epithelium

Blood

capillaries

Thin

squamous

epithelium

Terminal

sacs

Flat endothelium

cell of blood

capillary

Respiratory

bronchiole

Terminal

bronchiole

A

B

Figure 14.8

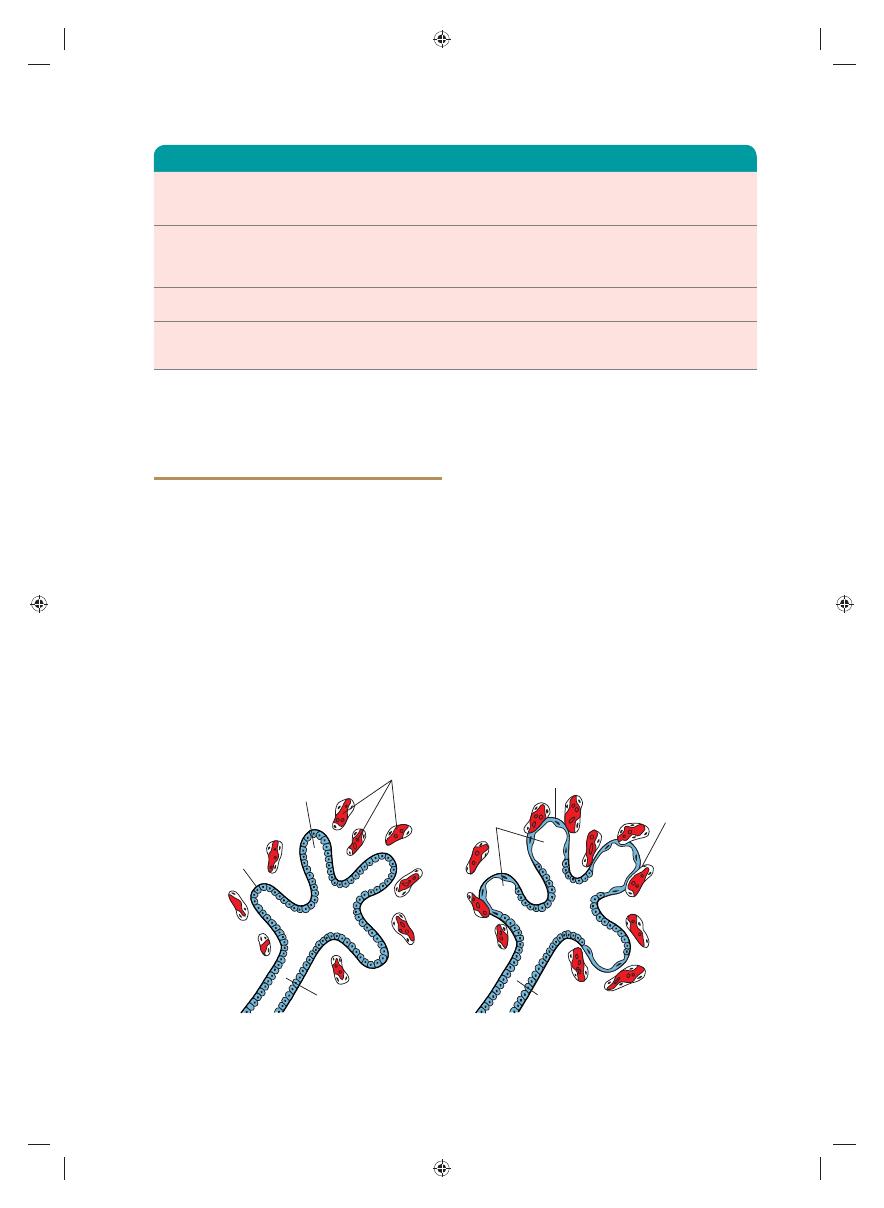

Histological and functional development of the lung. A. The canalicular period lasts from the 16th to the

26th week. Note the cuboidal cells lining the respiratory bronchioli. B. The terminal sac period begins at the end of the

sixth and beginning of the seventh prenatal month. Cuboidal cells become very thin and intimately associated with the

endothelium of blood and lymph capillaries or form terminal sacs (primitive alveoli).

bifurcation of the trachea is opposite the fourth

thoracic vertebra.

MATURATION OF THE LUNGS

Up to the seventh prenatal month, the bronchi-

oles divide continuously into more and smaller

canals (canalicular phase) and the vascular sup-

ply increases steadily (Fig. 14.8A). Terminal

bronchioles

divide to form respiratory bron-

chioles

and each of these divides into three to

six alveolar ducts (Fig. 14.8B). The ducts end in

terminal sacs (primitive alveoli)

that are sur-

rounded by fl at alveolar cells in close contact with

neighboring capillaries (Fig. 14.8B). By the end of

the seventh month, suffi cient numbers of mature

alveolar sacs and capillaries are present to guar-

antee adequate gas exchange, and the premature

infant is able to survive (Fig. 14.9) (Table 14.1).

During the last 2 months of prenatal life and

for several years thereafter, the number of termi-

nal sacs increases steadily. In addition, cells lining

the sacs, known as type I alveolar epithe-

lial cells

, become thinner, so that surrounding

capillaries protrude into the alveolar sacs

(Fig. 14.9). This intimate contact between

epithelial and endothelial cells makes up the

blood–air barrier. Mature alveoli

are not

present before birth. In addition to endothelial

cells and fl at alveolar epithelial cells, another cell

type develops at the end of the sixth month.

These cells, type II alveolar epithelial cells,

produce surfactant, a phospholipid-rich fl uid

capable of lowering surface tension at the air–

alveolar interface.

Before birth, the lungs are full of fl uid that

contains a high chloride concentration, little

protein, some mucus from the bronchial glands,

TABLE 14.1

Maturation of the Lungs

Pseudoglandular period

5–16 wk

Branching has continued to form

terminal bronchioles. No respiratory

bronchioles or alveoli are present.

Canalicular period

16–26 wk

Each terminal bronchiole divides into

two or more respiratory bronchioles,

which in turn divide into three to six

alveolar ducts.

Terminal sac period

26 wk to birth

Terminal sacs (primitive alveoli) form,

and capillaries establish close contact.

Alveolar period

8 mo to childhood

Mature alveoli have well-developed

epithelial endothelial (capillary)

contacts.

Sadler_Chap14.indd 205

Sadler_Chap14.indd 205

8/26/2011 4:17:42 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:42 AM

Thin squamous

epithelium

Blood

capillary

Lymph

capillary

Mature alveolus

Alveolar

duct

Respiratory bronchiole

Sadler_Chap14.indd 206

Sadler_Chap14.indd 206

8/26/2011 4:17:43 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:43 AM

Chapter 14 Respiratory System

207

Respiratory movements after birth bring air

into the lungs, which expand and fi ll the pleural

cavity. Although the alveoli increase somewhat in

size, growth of the lungs after birth is due pri-

marily to an increase in the number of respira-

tory bronchioles and alveoli. It is estimated that

only one-sixth of the adult number of alveoli

are present at birth. The remaining alveoli are

formed during the fi rst 10 years of postnatal life

through the continuous formation of new primi-

tive alveoli.

Summary

The respiratory system

is an outgrowth of the

ventral wall of the foregut, and the epithelium

of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and alveoli origi-

nates in the endoderm. The cartilaginous, mus-

cular, and connective tissue components arise in

the mesoderm. In the fourth week of develop-

ment, the tracheoesophageal septum separates

the trachea from the foregut, dividing the foregut

into the lung bud anteriorly and the esophagus

posteriorly. Contact between the two is main-

tained through the larynx, which is formed by

tissue of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches.

The lung bud develops into two main bronchi:

the right forms three secondary bronchi and

three lobes; the left forms two secondary bronchi

and two lobes. Faulty partitioning of the foregut

by the tracheoesophageal septum causes esopha-

geal atresias and TEFs (Fig. 14.3).

After a pseudoglandular (5 to 16 weeks) and

canalicular (16 to 26 weeks) phase, cells of the

cuboidal-lined respiratory bronchioles change

into thin, fl at cells, type I alveolar epithelial

cells

, intimately associated with blood and lymph

capillaries. In the seventh month, gas exchange

between the blood and air in the primitive

alveoli

is possible. Before birth, the lungs are

fi lled with fl uid with little protein, some mucus,

and surfactant, which is produced by type II

alveolar epithelial cells

and which forms a

phospholipid coat on the alveolar membranes.

At the beginning of respiration, the lung fl uid

is resorbed except for the surfactant coat, which

prevents the collapse of the alveoli during expi-

ration by reducing the surface tension at the air–

blood capillary interface. Absent or insuffi cient

surfactant in the premature baby causes respi-

ratory distress syndrome (RDS)

because of

collapse of the primitive alveoli (hyaline mem-

brane disease)

.

Growth of the lungs after birth is primarily

due to an increase in the number of respiratory

bronchioles and alveoli and not to an increase in

the size of the alveoli. New alveoli are formed

during the fi rst 10 years of postnatal life.

Problems to Solve

1.

A prenatal ultrasound revealed polyhydram-

nios, and at birth, the baby had excessive

fl uids in its mouth. What type of birth defect

might be present, and what is its embryologi-

cal origin? Would you examine the child

carefully for other birth defects? Why?

2.

A baby born at 6 months’ gestation is having

trouble breathing. Why?

Sadler_Chap14.indd 207

Sadler_Chap14.indd 207

8/26/2011 4:17:45 AM

8/26/2011 4:17:45 AM