L2 15 DEC 2020

Body fat distribution

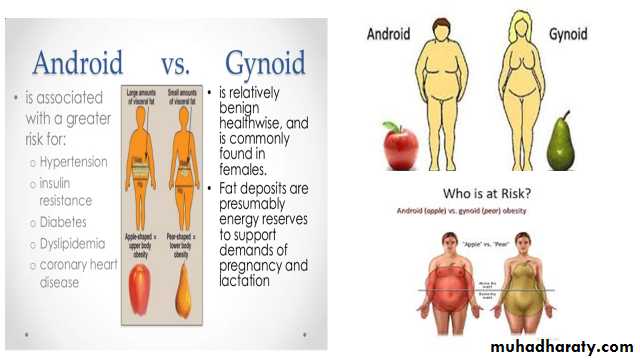

The distribution rather than the absolute amount of excess adipose tissue appears to be important. Increased intra-abdominal fat causes ‘central’ (‘abdominal’, ‘visceral’, ‘android’ or ‘apple-shaped’) obesity (which is more common in men and is more closely associated with T2DM , metabolic syndrome and CVS disease, which contrasts with subcutaneous fat accumulation causing ‘generalised’ (‘gynoid’ or ‘pear-shaped’) obesity.The key difference between these depots of fat may lie in their vascular anatomy, with intra-abdominal fat draining into the portal vein and thence directly to the liver. Thus many factors that are released from adipose tissue (including free fatty acids; ‘adipokines’, such as tumour necrosis factor alpha, adiponectin and resistin) may be at higher concentration in the liver and muscle, and hence induce insulin resistance and promote T2DM.

Recent research has also highlighted the importance of fat deposition within specific organs, especially the liver, as an important determinant of metabolic risk in the obese.

Aetiology

Accumulation of fat results from a discrepancy between energy consumption and energy expenditure that is too large to be defended by the hypothalamic regulation of BMR.

A continuous small daily positive energy balance of only 0.2–0.8 MJ (50–200 kcal; < 10% of intake) would lead to weight gain of 2–20 kg over a period of 4–10 years.

Given the cumulative effects of subtle energy excess, body fat content shows ‘tracking’ with age, such that obese children usually become obese adults.

Weight tends to increase throughout adult life, as BMR and physical activity decrease.

Susceptibility to obesity

It is not true that obese subjects have a ‘slow metabolism’, since their BMR is higher than that of lean subjects. Twin and adoption studies confirm a genetic influence on obesity.The pattern of inheritance suggests a polygenic disorder, with small contributions from a number of different genes, together accounting for 25–70% of variation in weight.

Recent results have identified a handful of genes that influence obesity, some of which encode proteins known to be involved in the control of appetite or metabolism and some of which have an unknown function.

These genes account for less than 5% of the variation in body weight, however. Genes also influence fat distribution and therefore the risk of the metabolic consequences of obesity, such as type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

A few rare single-gene disorders have been identified that lead to severe childhood obesity. These include:-

• Mutations of the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), which account for approximately 5% of severe early-onset obesity.

• Defects in the enzymes processing propiomelanocortin (POMC, the precursor for adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)) in the hypothalamus

• Mutations in the leptin gene which can be treated by leptin injections.

• Additional genetic conditions in which obesity is a feature include Prader–Williand Lawrence–Moon–Biedl syndromes.

Endocrine factors

• Hypothyroidism• Cushing’s syndrome

• Insulinoma

• Hypothalamic tumours or injury

Potentially reversible causes of weight gain

Drug treatments

• Atypical antipsychotics (e.g. olanzapine)

• Sulphonylureas, thiazolidinediones, insulin

• Pizotifen

• Glucocorticoids

• Sodium valproate

• β-blockers

Clinical features and investigations

In assessing obesity, the aims are to:

• Quantify the problem

• Exclude an underlying cause

• Identify complications

• Reach a management plan.

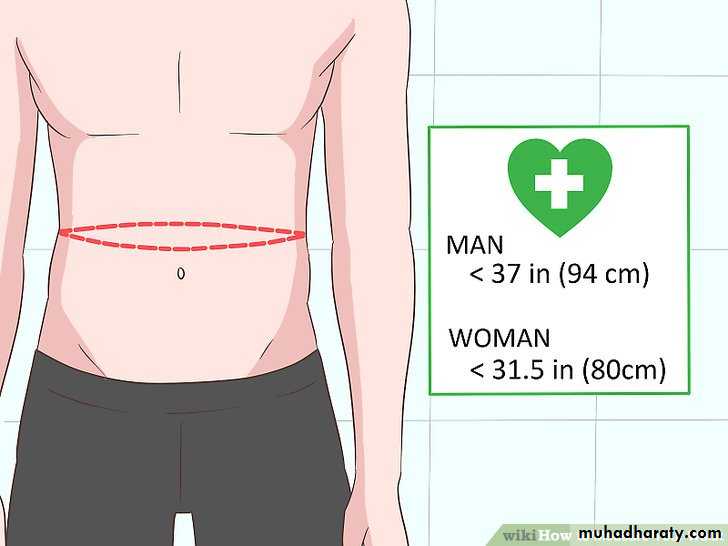

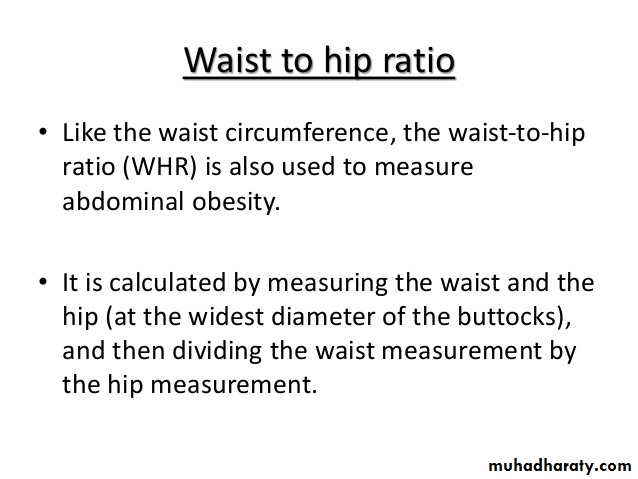

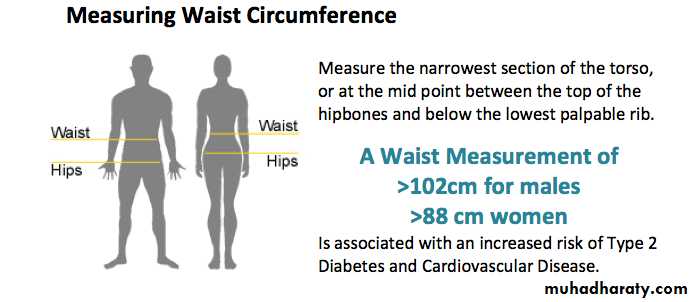

Severity of obesity can be quantified using the BMI and waist circumference.

The risk of metabolic and CV complications of obesity is higher in those with a high waist circumference; lower levels of BMI and waist circumference indicate higher risk in Asian populations.

A dietary history may be helpful in guiding dietary advice but is notoriously susceptible to under-reporting of food consumption.

It is important to consider ‘pathological’ eating behaviour (such as binge eating, nocturnal eating or bulimia. Alcohol is an important source of energy intake and should be considered in detail.

Assessment of the diverse complications of obesity

Thorough history, examination and screening investigationsThe impact of obesity on the patient’s life and work is a major consideration.

Assessment of other cardiovascular risk factors is important.

Associated T2DM and dyslipidemia are detected by measurement of blood glucose or HbA1c and a serum lipid profile, ideally in a fasting morning sample.

Elevated serum transaminases occur in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Quantifying obesity with BMI and waist circumference for risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease

Among Asians,

BMI > 23.0 is overweight and > 25.0 is obese.

waist circumference does not add to the increased risk when the BM>35 I.

?

Management

Relevant comorbidities include:-• Type 2 diabetes

• Hypertension

• Cardiovascular disease

• Sleep apnoea and

• Waist circumference of > 102 cm in men or 88 cm in women.

Lifestyle advice

• Adopting regular eating patterns and maximising physical activity are advised, with reference to the modest extra activity required to increase physical activity level (PAL) ratios.• Where possible, this should be incorporated in the daily routine (e.g. walking rather than driving to work), as this is more likely to be sustained. Alternative exercise (e.g. swimming) may be considered if musculoskeletal complications prevent walking.

• Changes in eating behaviour including:-

• Food selection• Portion size control

• Avoidance of snacking

• Regular meals to encourage satiety and

• substitution of sugar with artificial sweeteners) should be discussed. Regular support from a dietitian or attendance at a weight loss group may be helpful.

Weight loss diets

In overweight people, adherence to the lifestyle advice given above may gradually induce weight loss.In obese patients, more active intervention is usually required to lose weight before conversion to the ‘weight maintenance’ advice.

A significant industry has developed in marketing diets for weight loss.

These vary substantially in their balance of macronutrients, but there is little evidence that they vary in their medium-term (1-year) efficacy.

Most involve recommending a reduction of daily total energy intake of (600 kcal) from the patient’s normal consumption.

Modelling data that take into account the reduced energy expenditure as weight is lost suggest that a reduction of energy intake of 100 kJ per day will lead to an eventual body weight change of about 1 kg, with half of the weight change being achieved in about 1 year and 95% of the weight change in about 3 years.

100 kJ per day will lead to an eventual body weight change of about 1 kg

Half of the weight change being achieved in about 1 year

95% of the weight change in about 3 years.

Weight loss is highly variable and patient adherence is the major determinant of success.

There is some evidence that weight loss diets are most effective in their early weeks and that adherence is improved by novelty of the diet; this provides some justification for switching to a different dietary regimen when weight loss slows on the first diet.Vitamin supplementation is wise in those diets in which macronutrient balance is markedly disturbed.

Patient adherence

Novelty

In some patients, more rapid weight loss is required, e.g. in preparation for surgery.

There is no role for starvation diets, which risk profound loss of muscle mass and the development of arrhythmias (and even sudden death) secondary to elevated free fatty acids, ketosis and deranged electrolytes.Very-low calorie diets (VLCDs) can be considered for short-term rapid weight loss, producing losses of 1.5–2.5 kg/week, compared to 0.5 kg/week on conventional regimens, but require the supervision of an experienced physician and nutritionist.

In some patients, more rapid weight loss is required, e.g. in preparation for surgery.

There is no role for starvation diets, which risk profound loss of muscle mass and the development of arrhythmias (and even sudden death) secondary to elevated free fatty acids, ketosis and deranged electrolytes.Very-low calorie diets (VLCDs) can be considered for short-term rapid weight loss, producing losses of 1.5–2.5 kg/week, compared to 0.5 kg/week on conventional regimens, but require the supervision of an experienced physician and nutritionist.

The composition of the diet should ensure a minimum of 50 g of protein each day for men and 40 g for women to minimize muscle degradation.

Energy content should be a minimum of (400 kcal) for women of height < 1.73 m, and (500 kcal) for all men and for women taller than 1.73 m.

Side-effects are a problem in the early stages and include:-

• Orthostatic hypotension

• Headache

• Diarrhoea and

• Nausea.

Drugs

A huge investment has been made by the pharmaceutical industry in finding drugs for obesity. The side-effect profile has limited the use of many agents, with notable withdrawals from clinical use of sibutramine (increased cardiovascular events) and rimonabant (psychiatric side-effects) in recent years.Orlistat has been available for many years, and four drugs or drug combinations have recently been approved in the USA and two of these in Europe.

There is no role for diuretics, or for thyroxine therapy without biochemical evidence of hypothyroidism.

Drug therapy should always be used as an adjunct to lifestyle advice and support, which should be continued throughout treatment.

Orlistat inhibits pancreatic and gastric lipases and thereby decreases the hydrolysis of ingested triglycerides, reducing dietary fat absorption by approximately 30%.

The drug is not absorbed and adverse side-effects relate to the effect of the resultant fat malabsorption on the gut: namely, loose stools, oily spotting, faecal urgency, flatus and the potential for malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Orlistat at the standard dose of 120 mg is taken with each of the three main meals of the day; a lower dose (60 mg) is available without prescription in some countries.

Its efficacy may be explained because patients taking orlistat adhere better to low-fat diets in order to avoid unpleasant gastrointestinal side-effects.

The combination of low-dose phentermine (sympathomimetic amine induces anorectic effect and topiramate extended release) (Qsymia) has been approved in the USA; this results in weight loss of approximately 6% greater than placebo and benefits lipids and glucose concentrations.

Concerns over teratogenicity of topiramate and cardiovascular effects of phentermine have so far precluded

its approval in Europe.

.

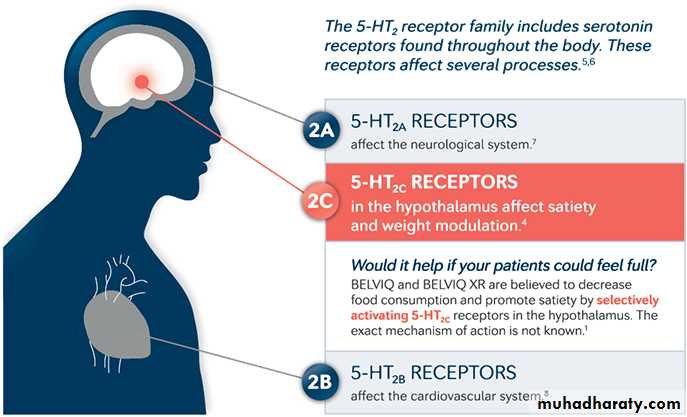

The 5-HT2c inhibitor lorcaserin is also approved in the USA; it is moderately effective and has a relatively low rate of adverse effects.

The combination of the opioid antagonist naltrexone and the noradrenaline (norepinephrine)/ dopamine re-uptake inhibitor bupropion is also effective. The main adverse effects are dry mouth and constipation.

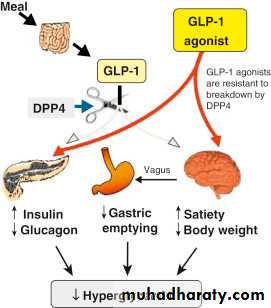

Finally, a higher dose of the injectable glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide (3 mg) is also approved for use and has been shown to reduce the risk of diabetes in patients with pre-diabetes

Drug therapy is usually reserved for patients with high risk of complications from obesity and its optimum timing and duration are controversial.

There is evidence that those patients who demonstrate early weight loss (usually defined as 5% after 12 weeks on the optimum dose) achieve greater and longer-term weight loss, and this is reflected in most guidelines for the use of drugs for obesity.

Treatment can be stopped in non-responders at this point and an alternative treatment considered.

How we define responders and non-responders ??????

Although life-long therapy is advocated for many drugs that reduce risk on the basis of relatively short-term research trials (e.g. drugs for hypertension and osteoporosis), some patients who continue to take anti-obesity drugs tend to regain weight with time; this may partly reflect age-related weight gain, but significant weight gain should prompt reinforcement of lifestyle advice and, if this is unsuccessful, drug therapy should be discontinued .