Fasciola hepatica

Adult Egg

Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758 was the first trematode to be described (de brie,

1379). It is particularly prevalent in sheep- raising areas. In several countries

human infection is an increasing clinical and public health problem.

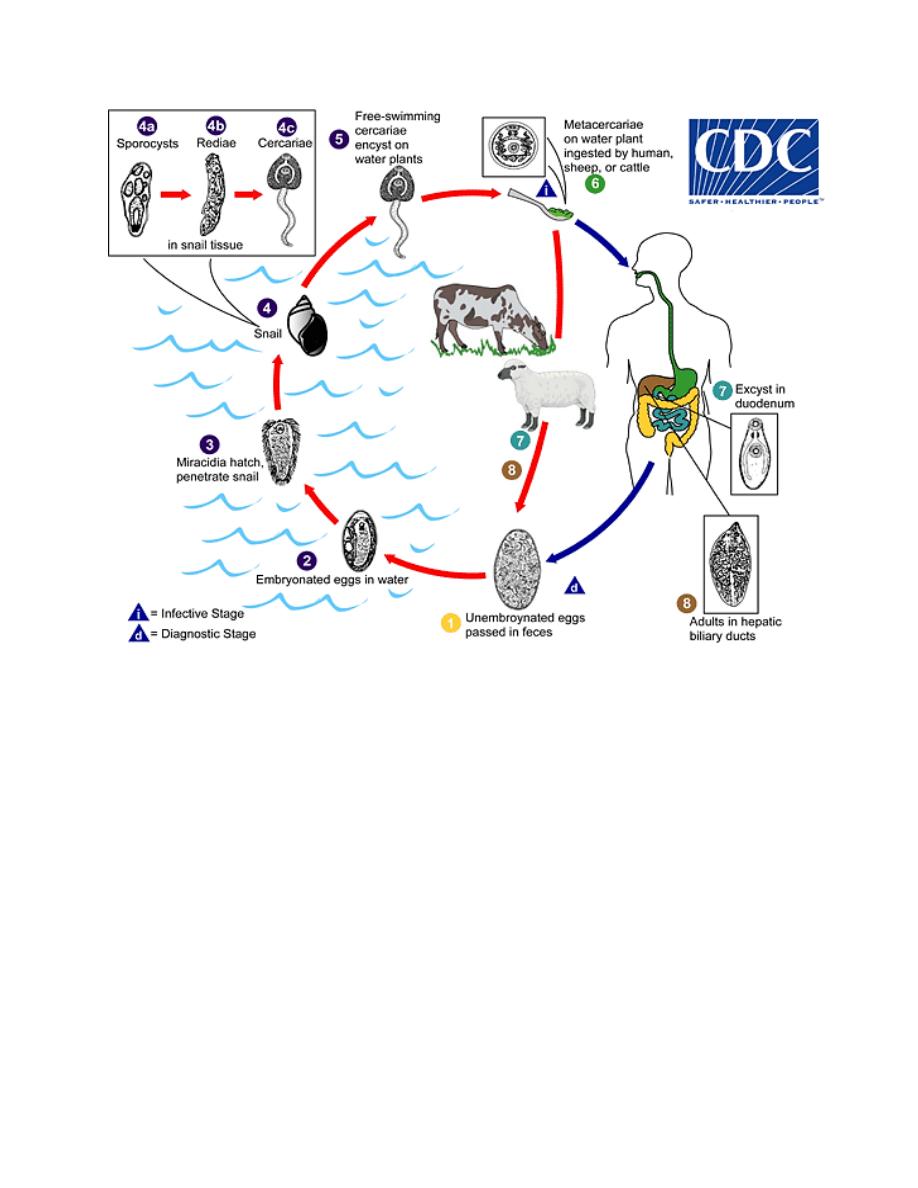

Morphology, Biology and life cycle.

The mature Fasciola hepatica is a relatively large worm, measuring up to 30 by 13

mm. It is more or less flattened and leaf-like along the margins, fleshy throughout

the middle. F. hepatica adults reside typically in bile passages and gall bladder.

Occasionally they fail to reach this location and are found ectopically in the

peritoneal cavity or other sites. The eggs are unembryonated when expelled. They

pass from the common bile duct into the duodenum and intestinal tract of the host,

to be evacuated in the stools. These eggs are large (130 to 150 microns by 63 to 90

microns), relatively thin-shelled, and have a small, flat operculum at one end. They

require 9 to 15 days to mature in fresh water at an optimum temperature of 22° to

25°C. Upon hatching, the miracidium invades a lymnaeid snail (Lymnaea

truncatula), enters the tissues and transforms into a sporocyst within 30 days,

second and third generation rediae and cercariae have been produced. Then the

cercariae swam out of the snail, and after crawling upon moist vegetation shed

their tail, round up and encyst as minute spherules (metacercariae). These cysts

survive for a considerable time in a moist atmosphere. When viable cysts ingested

by human, reach the duodenal or jejunal level of the intestine, they excyst and the

metacercariae actively burrow through the intestinal wall, migrate across the

peritoneal cavity to the liver, then eat their way as they burrow through the hepatic

parenchyma to the bile ducts, where they develop into adults in 3 to 4 months after

exposure. They feed on the tissues through which they pass, only incidentally

consuming extravasated blood.

Pathogenicity and symptomatology

The migration of young Fasciola hepatica en route through the parenchyma to the

bile ducts cause both traumatic damage and toxic irritation with necrosis of tissue

along their pathway. In the bile passages, they produce hyperplasia of the biliary

epithelium, with leukocyte infiltration and development of a fibrous capsule

around the ducts. Early symptoms in human infections consist of right upper

quadrant abdominal pain, fever and hepatomegaly; biliary colic with coughing and

vomiting; marked jaundice; diarrhea; irregular fever; significant eosinophilia. Later

there may be profound systemic toxemia.

False fascioliasis refers to the recovery of the eggs of Fasciola in the stool

following ingestion of infected livers of sheep, goats or cattle, raw or undercooked.

Diagnosis

Most cases of true fascioliasis hepatica are first apprehended by of the eggs in the

patient’s stool. These require differentiation from eggs of Fasciolopsis buski,

which are almost identical in size and appearance. The difficulty may be avoided

by obtaining samples of uncontaminated bile for microscopic examination. In cases

of false fascioliasis, eggs of Fasciola will no longer appear in the feces a few days

after the patient has been placed on a liver-free diet.

Treatment

The recommended treatment options for fascioliasis (liver fluke infection with F.

hepatica or F. gigantica), include triclabendazole which is the drug of choice. The

drug is given by mouth, usually in two doses. Most people respond well to the

treatment. Praziquantel, previously used as an alternative drug is no longer

recommended due to poor efficacy against Fasciola species.

Epidemiology

Human infection is usually due to where eating freshwater cress to which the

metacercarial cysts are attached. Several hundred published human cases in Latin

America, Mediterranean countries, in which the infection is relatively frequent and

clinically important.

Control

Fundamental control requires the institution of measure to eradicate natural

infection in sheep and other herbivorous mammals. Since most human infections

results from use of water cress as salad greens, control of human fascioliasis

hepatica will usually be obtained if this delicacy is omitted from the diet in

endemic areas. Application of the molluscicide has proven effective against the

lymnaeid snail intermediate hosts in several European countries.

Fasciola gigantica

Fasciola gigantica cobbold, 1856, the giant liver fluke, differs from F. hepatica in

its greater length, and larger size of the eggs (160 to 190 microns by 70 to 90

microns). The life cycle parallels that of F .hepatica, including lymnaeid snails

(Radix auricularia) as intermediate hosts. Human infections have been reported

from West Africa, Vietnam,

Uzbekistan

, Iraq, and Hawaii. Clinical aspects of this

infection are essentially the same as in fascioliasis hepatica.