Dr.Mushtaq Talib Hussein

F.I.B.M.S(Ortho.)- C.A.B.O(Ortho.)

Hand injuries

Hand injuries – the commonest of all injuries – are important out of all proportion to

their apparent severity, because of the need for perfect function.

Superficial injuries and severe fractures are obvious, but deeper injuries are often

poorly disclosed. It is important in the initial examination to assess the circulation, soft-

tissue cover, bones, joints, nerves and tendons.

X-rays should include at least three views (posteroanterior, lateral and oblique), and

with finger injuries the individual digit must be x-rayed.

Most hand injuries can be dealt with under local or regional anaesthesia; a general

anaesthetic is only rarely required.

Circulation If the circulation is threatened, it must be promptly restored, if necessary by

direct repair or vein grafting.

Swelling Swelling must be controlled by elevating the hand and by early and repeated

active exercises.

Splintage Incorrect splintage is a potent cause of stiffness; it must be appropriate and it

must be kept to a minimum length of time.

(position of safety) – with the metacarpo-phalangeal joints flexed at least 70 degrees

and the interphalangeal joints almost straight.

Skin cover Skin damage demands wound toilet followed by suture, skin grafting, local

flaps, pedicled flaps or (occasionally) free flaps. Treatment of the skin takes precedence

over treatment of the fracture.

Nerve and tendon injury Generally, the best results will follow primary repair of

tendons and nerves. Occasionally grafts are required.

METACARPAL FRACTURES

The metacarpal bones are vulnerable to blows and falls upon the hand, or the

longitudinal force of the boxer’s punch. Injuries are common and the bones may fracture

at their base, in the shaft or through the neck.

METACARPAL SHAFT

Oblique or transverse fractures with slight displacement require no reduction.

Splintage also is unnecessary, but a firm crepe bandage may be comforting;

Transverse fractures with considerable displacement are reduced by traction and

pressure. Reduction can sometimes be held by a plaster slab extending from the forearm

over the fingers (only the damaged ones).

Spiral fractures are liable to rotate; if so, they should be perfectly reduced and fixed

with lag screws and a plate, or percutaneous wires.

FRACTURES OF THE METACARPAL NECK

A blow may fracture the metacarpal neck, usually of the fifth finger (the ‘boxer’s

fracture’) and occasionally one of the others. There may be local swelling, with flattening

of the knuckle. X-rays show an impacted transverse fracture with volar angulation of the

distal fragment.

The hand is immobilized in a gutter splint with the MCP joint flexed and the

interphalangeal(IP) joints straight until discomfort settles– a week or two – and then the

hand is mobilized.

FRACTURE OF THE THUMB METACARPAL

Three types of fracture are encountered: impacted fracture of the metacarpal base;

Bennett’s fracture-dislocation of the carpo-metacarpal (CMC) joint; and Rolando’s

comminuted fracture of the base.

FRACTURES OF THE PROXIMAL AND

MIDDLE PHALANGEAL SHAFTS

The phalanx may fracture in various ways:

•

Transverse fracture of the shaft, often with forward angulation.

•

Spiral fracture of the shaft, from a twisting injury.

•

Comminuted fracture, usually due to a crush injury and often associated with

significant tendon damage and skin loss.

•

Avulsion of a small fragment of bone.

•

Metaphyseal fracture at the base of the proximal phalanx, commonly seen in

osteopaenic bone.

•

Intra-articular fractures:

Treatment

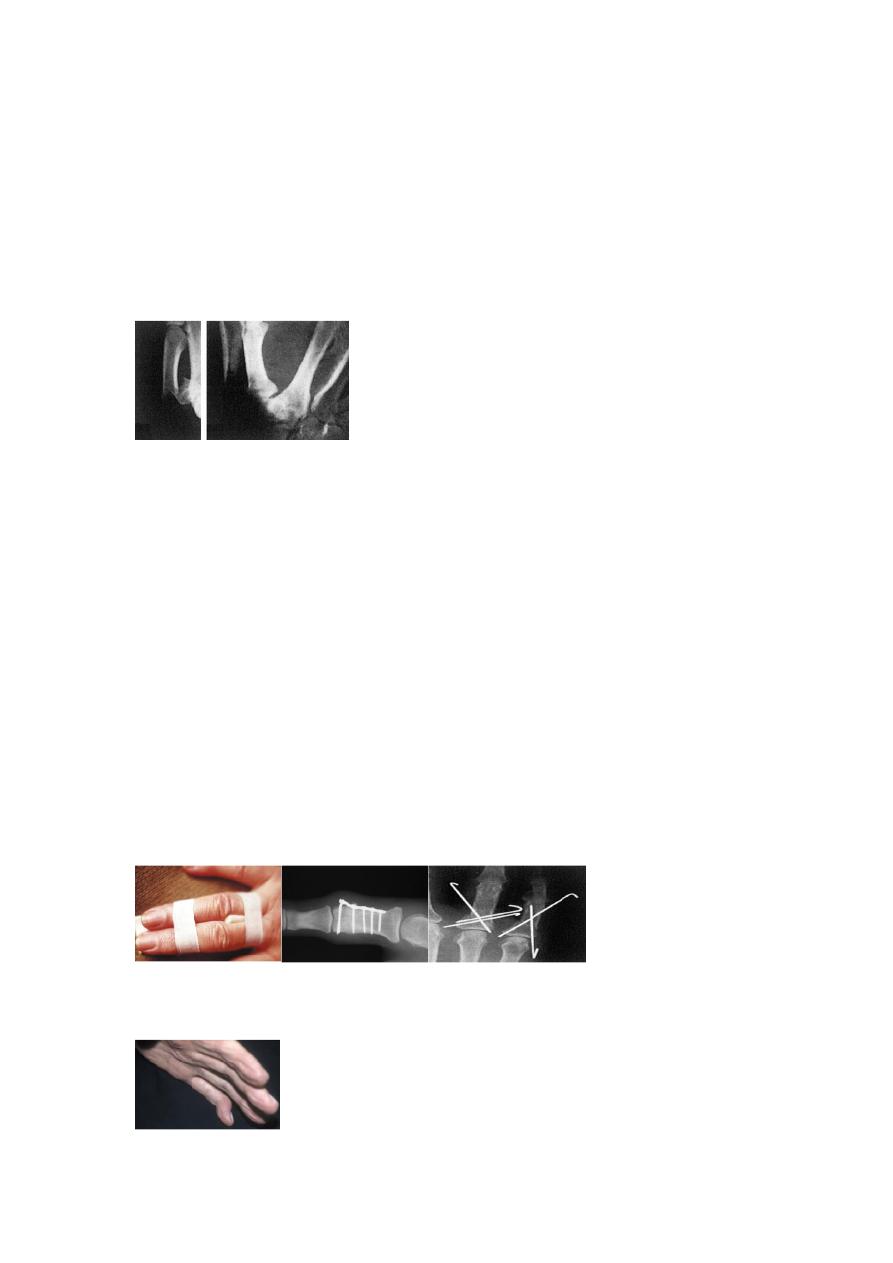

Undisplaced fractures can be treated by ‘functional splintage’. The finger is strapped to

its neighbour (‘buddy strapping’)

for 2–3 weeks.

Displaced fractures must be reduced and immobilized. If a reduction cannot be

achieved, or if it is unstable and the position slips, then surgery is needed. The technique

depends upon the configuration of the fracture.

Mallet finger injury

After a sudden flexion injury (e.g. stubbing the tip of the finger) the terminal phalanx

droops and cannot be straightened actively.

LIGAMENT INJURIES

ULNAR COLLATERAL LIGAMENT OF THE THUMB METACARPO-PHALANGEAL JOINT

(‘GAMEKEEPER’S THUMB’; ‘SKIER’S THUMB’)

this injury is seen in skiers who fall onto the extended thumb, forcing it into

hyperabduction. A small flake of bone may be pulled off at the same time. The resulting

loss of stability may interfere markedly with prehensile (pinching) activities.

Clinical assessment

On examination there is tenderness and swelling precisely over the ulnar side of the

thumb metacarpo-phalangeal joint. An x-ray is essential, to exclude a fracture before

carrying out any stress tests.

Treatment

Partial tears can be treated by a short period (2–4 weeks) of immobilization in a splint

followed by increasing movement. Pinch should be avoided for 6–8 weeks. Complete

tears need operative repair.

OPEN INJURIES OF THE HAND

Over 75 per cent of work injuries affect the hands; inadequate treatment costs the patient (and

society) dear in terms of functional disability.

Clinical assessment

Open injuries comprise tidy or ‘clean’ cuts, lacerations, crushing and injection injuries,

burns and pulp defects. The precise mechanism of injury must be understood. Was the

instrument sharp or blunt? Clean or dirty?

Skin damage is important.

The circulation to the hand and each digit must be assessed.

Sensation is tested in the territory of each nerve.

Tendons must be examined with similar care.

Primary treatment

PREOPERATIVE CARE

The patient may need treatment for pain and shock. If the wound is contaminated, it

should be rinsed with sterile crystalloid; antibiotics should be given as soon as possible.

WOUND EXPLORATION

Under general or regional anaesthesia, the wound is cleaned and explored.

Fractures are reduced and held appropriately (splintage, K-wires, external fixator or

plate and screws).

Joint capsule and ligaments are repaired.

Artery and vein repair may be needed if the hand or finger is ischaemic. This done with

the aid of an operating microscope.

Severed nerves are sutured under an operating microscope (or at least loupe

magnification).

Extensor tendon repair is not as easy and the results not as reliable as some have

suggested. Repair and postoperative management should be meticulous.

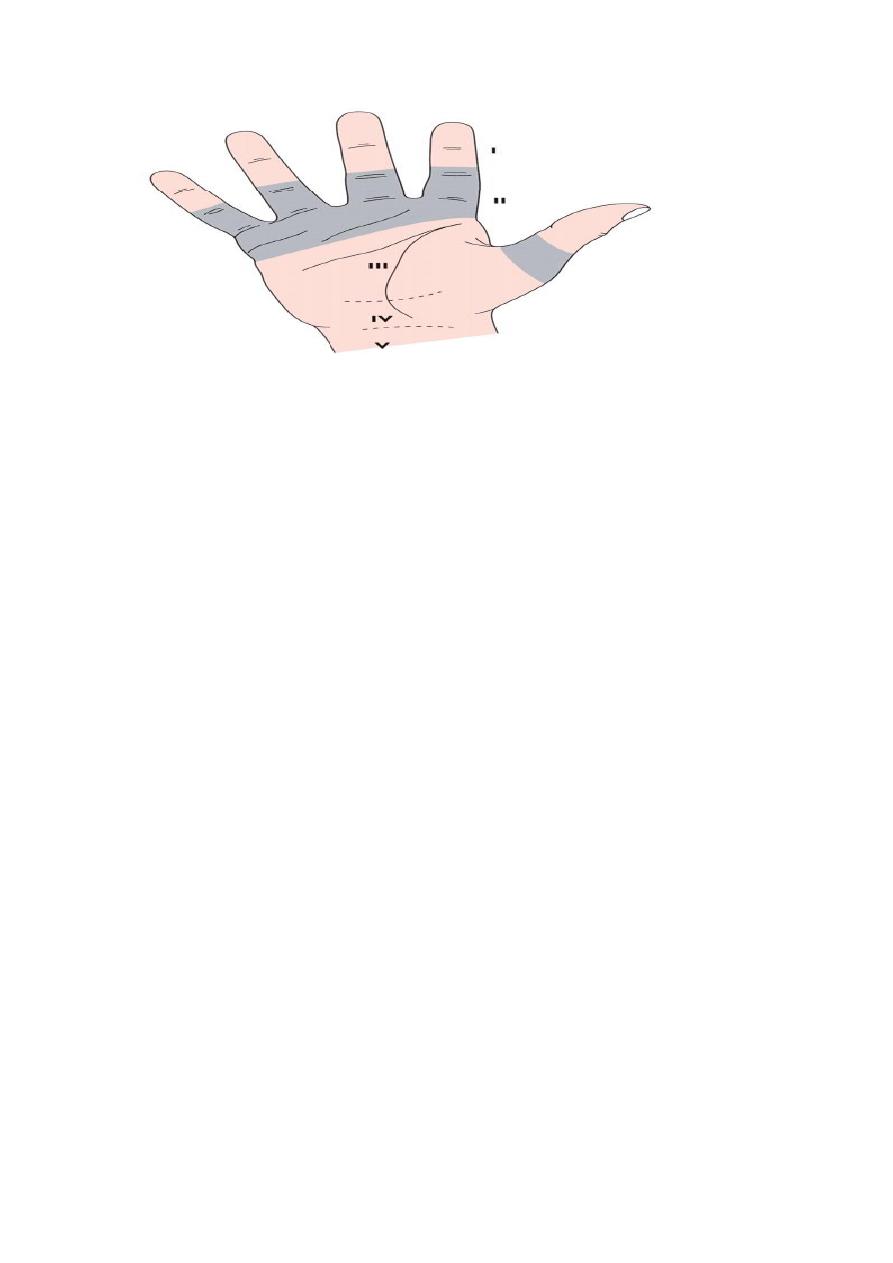

Flexor tendon repair is even more challenging, particularly in the region between the

distal palmar crease and the flexor crease of the proximal interphalangeal joint where

both the superficial and deep tendons run together in a tight sheath (Zone II or, more

dramatically, ‘no man’s land’ because injuries in this zone are the most dangerous).

The zones of injury

I – Distal to the insertion of flexor digitorum superficialis. II – Between the opening of

the flexor sheath (the distal palmar crease) and the insertion of flexor superficialis. IIII – Between the end of

the carpal tunnel and the beginning of the flexor sheath. IV – Within the carpal tunnel. V – Proximal to the

carpal tunnel.

Amputation of a finger as a primary procedure should be avoided unless the damage

involves many tissues and is clearly irreparable.

CLOSURE

Skin grafts are conveniently taken from the inner aspect of the upper arm. If tendon or

bare bone is exposed, this must be covered by a rotation or pedicled flap.

DRESSING AND SPLINTAGE

The wound is covered with a single layer of paraffin gauze and ample wool roll. A light

plaster slab holds the wrist and hand in the position of safety (wrist extended,

metacarpo-phalangeal joints flexed to 90 degrees, interphalangeal joints straight, thumb

abducted).

Postoperative management

Following an operation, the hand is kept elevated in a roller towel or high sling.

Movements of the hand must be commenced within a few days at most. Splintage should

allow as many joints as possible to be exercised, consistent with protecting the repair.

AMPUTATION

Indications A finger is amputated only if it remains painful or unhealed, or if it is a

nuisance (i.e. the patient cannot bend it, straighten it or feel with it), and then only if

repair is impossible or uneconomic.