Injuries of the upper limbs

Dr.Mushtaq Talib Hussein

F.I.B.M.S(ortho.) C.A.B.O(ortho.)

FRACTURES OF THE CLAVICLE

In children the clavicle fractures easily, but it almost invariably unites rapidly and without

complications In adults this can be a much more troublesome injury.

A fall on the shoulder or the outstretched hand may break the clavicle.

Clinical features

The arm is clasped to the chest to prevent movement. A subcutaneous lump may be obvious

and occasionally a sharp fragment threatens the skin.

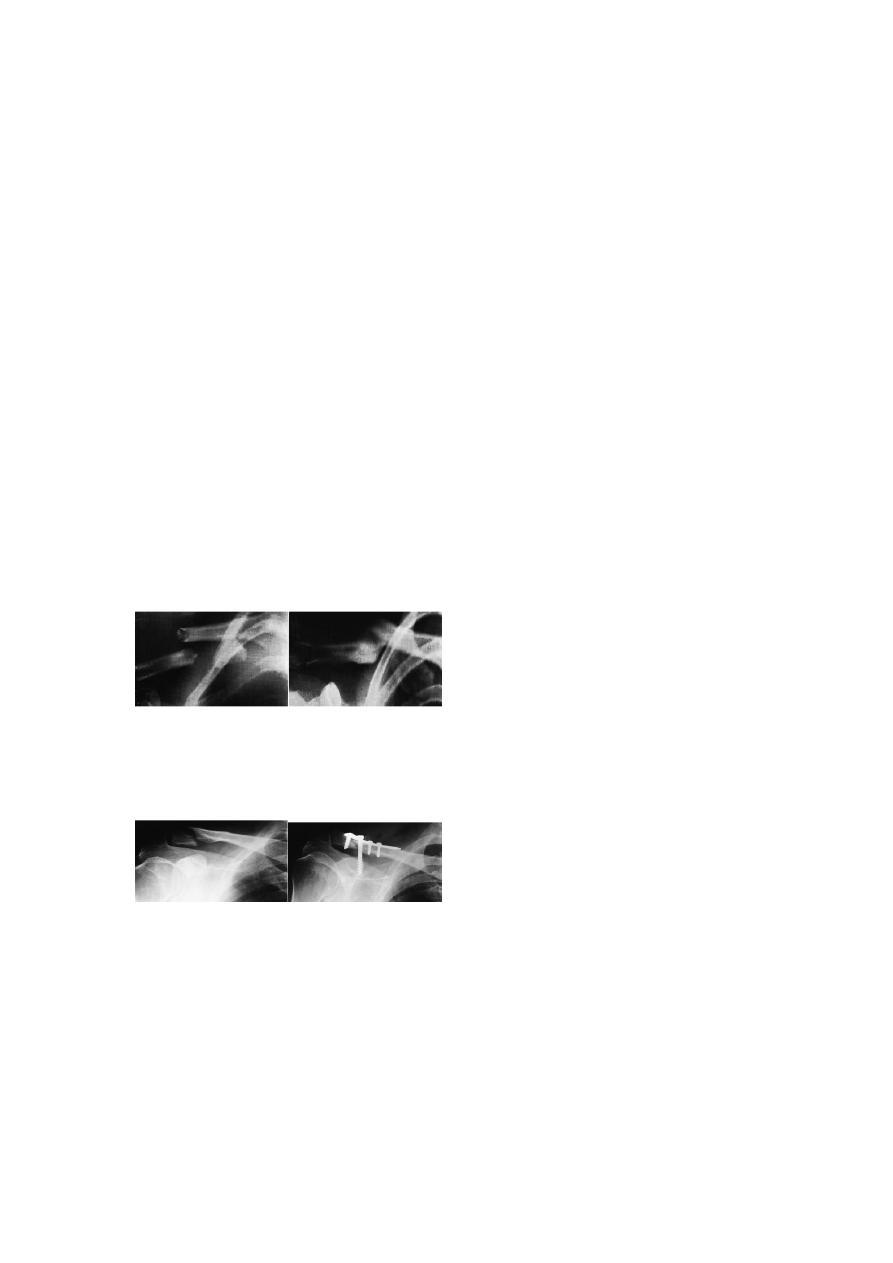

Imaging

Radiographic analysis requires at least an anteroposterior view and another taken with

a 30 degree cephalic tilt.

Clavicle fractures are usually classified on the basis of their location: Group I (middle

third fractures), Group II (lateral third fractures) and Group III(medial third fractures).

Treatment

MIDDLE THIRD FRACTURES

There is general agreement that undisplaced fractures should be treated non-

operatively.

Non-operative management consists of applying a simple sling for comfort. It is subsides

(between 1–3 weeks) and the patient is then discarded once the pain encouraged to

mobilize the limb as pain allows.

LATERAL THIRD FRACTURES

non-operative management is usually appropriate for minimally displaced fractures

while Displaced lateral third fractures are associated with disruption of the

coracoclavicular ligaments and are therefore unstable injuries,

Surgery to stabilize the

fracture is often recommended.

Complications

EARLY

damage to the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus injuries are all very rare.

LATE

Non-union In displaced fractures of the shaft nonunion occurs in 1–15 per cent. Lateral

clavicle fractures have a higher rate of nonunion(11.5–40 per cent).

Malunion All displaced fractures heal in a nonanatomical position with some shortening

and angulation, however most do not produce symptoms.

Stiffness of the shoulder This is common but temporary; it results from fear of moving

the fracture.

FRACTURES OF THE SCAPULA

The body of the scapula is fractured by a crushing force, which usually also fractures

ribs and may dislocate the sternoclavicular joint.

The arm is held immobile and there

may be severe bruising over the scapula or the chest wall. Because of the energy

required to damage the scapula, fractures of the body of the scapula are often associated

with severe injuries to the chest, brachial plexus, spine, abdomen and head. Careful

neurological and vascular examinations are essential.

ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT INJURIES

Acute injury of the acromioclavicular joint is common and usually follows direct trauma.

Chronic sprains, often associated with degenerative changes, are seen in people engaged

or occupations such as working with jack-hammers in athletic activities like

weightlifting and other heavy vibrating tools.

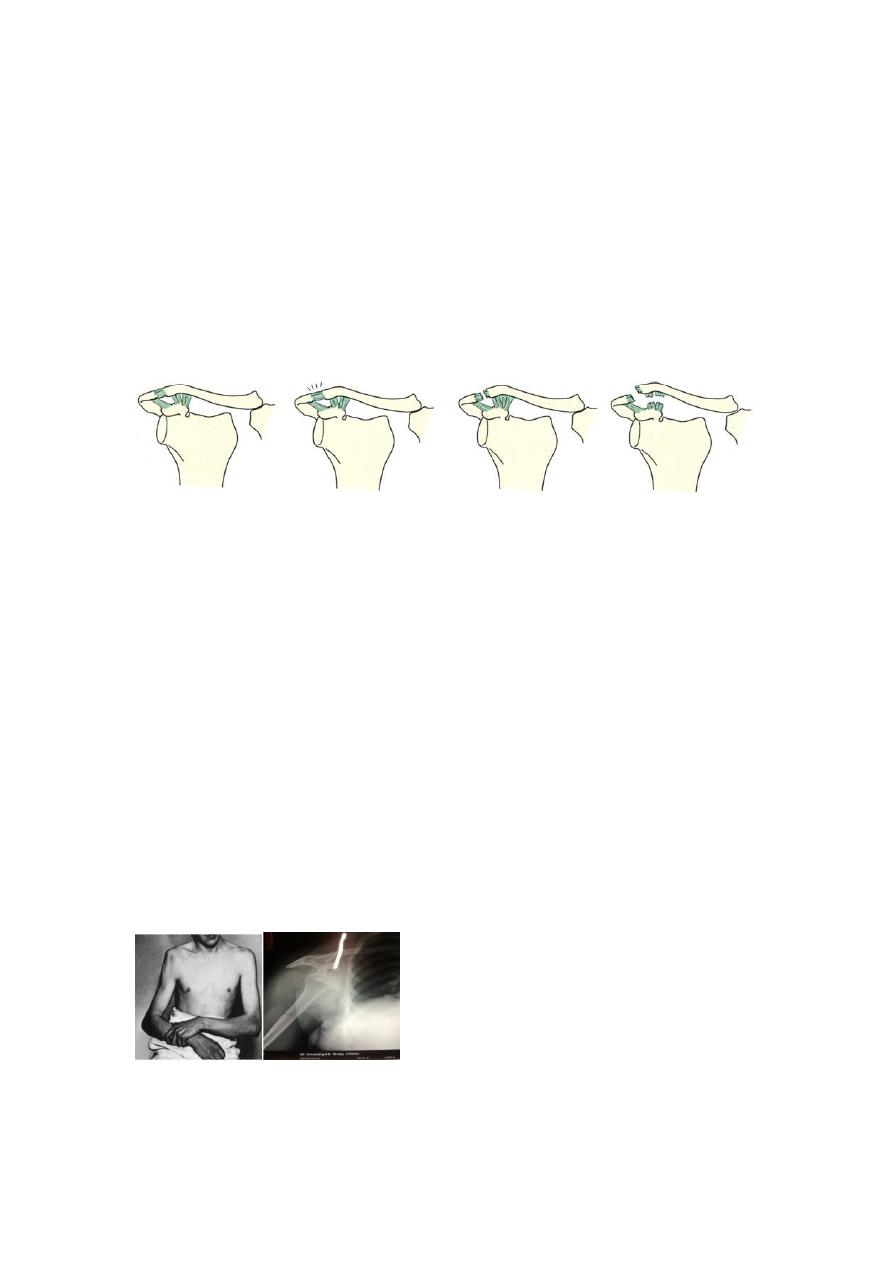

A b c d

Acromioclavicular joint injuries (a)

Normal joint.

(b)

Sprained acromioclavicular joint; no

displacement.

(c)

Torn capsule and subluxation but coracoclavicular ligaments intact.

(d)

Dislocation

with torn coracoclavicular ligaments.

DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

Of the large joints, the shoulder is the one that most commonly dislocates. This is due to

a number of factors: the shallowness of the glenoid socket; the extraordinary range of

movement; underlying conditions such as ligamentous laxity or glenoid dysplasia;

and the sheer vulnerability of the joint during stressful activities of the upper limb.

ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

Mechanism of injury

Dislocation is usually caused by a fall on the hand. The head of the humerus is driven

forward, tearing the capsule and producing avulsion of the glenoid labrum (the Bankart

lesion).

Clinical features

Pain is severe. The patient supports the arm with the opposite hand and is loathe to

permit any kind of examination. The lateral outline of the shoulder may be flattened and,

if the patient is not too muscular, a bulge may be felt just below the clavicle. The arm

must always be examined for nerve and vessel injury before reduction is attempted.

X-Ray

The anteroposterior x-ray will show the overlapping shadows of the humeral head and

glenoid fossa, with the head usually lying below and medial to the socket.

Treatment

Various methods of reduction have been described, some of them now of no more than

historical interest. In a patient who has had previous dislocations, simple traction on the

arm may be successful. Usually, sedation and occasionally general anaesthesia is

required.

With Stimson’s technique, the patient is left prone with the arm hanging over the side of

the bed. After15 or 20 minutes the shoulder may reduce.

In the Hippocratic method, gently increasing traction is applied to the arm with the

shoulder in slight abduction, while an assistant applies firm counter traction to the body

(a towel slung around the patient’s chest, under the axilla, is helpful).

An x-ray is taken to confirm reduction and exclude

a

fracture. When the patient is fully

awake, active abduction is gently tested to exclude an axillary nerve injury and rotator

cuff tear. The median, radial, ulnar and musculocutaneous nerves are also tested and the

pulse is felt. The arm is rested in a sling for about three weeks in those under 30 years of

age (who are most prone to recurrence) and for only a week in those over 30 (who are

most prone to stiffness).

Complications

EARLY

Rotator cuff tear This commonly accompanies anterior dislocation, particularly in older

people.

Nerve injury The axillary nerve is most commonly injured; the patient is unable to

contract the deltoid muscle and there may be a small patch of anaesthesia over the

muscle.

Vascular injury The axillary artery may be damaged, particularly in old patients with

fragile vessels.

Fracture-dislocation If there is an associated fracture of the proximal humerus, open

reduction and internal fixation may be necessary.

LATE

Shoulder stiffness Prolonged immobilization may lead to stiffness of the shoulder,

especially in patients over the age of 40.

Unreduced dislocation Surprisingly, a dislocation of the shoulder sometimes remains

undiagnosed. This is more likely if the patient is either unconscious or very old.

Recurrent dislocation If an anterior dislocation tears the shoulder capsule, repair

occurs spontaneously following reduction and the dislocation may not recur; but if the

glenoid labrum is detached, or the capsule is stripped off the front of the neck of the

glenoid, repair is less likely and recurrence is more common.

POSTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

Posterior dislocation is rare, accounting for less than 2 per cent of all dislocations

around the shoulder.

Indirect force producing marked internal rotation and adduction needs be very severe

to cause a dislocation. This happens most commonly during a fit or convulsion, or with

an electric shock.

The diagnosis is frequently missed – partly because reliance is placed

on a single anteroposterior x-ray(which may look almost normal) and partly because

those attending to the patient fail to think of it.

INFERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER (LUXATIO ERECTA)

Inferior dislocation is rare but it demands early recognition because the consequences

are potentially very serious. Dislocation occurs with the arm in nearly full

abduction/elevation. The humeral head is levered out of its socket and pokes into the

axilla; the arm remains fixed in abduction.

FRACTURES OF THE PROXIMAL HUMERUS

Fractures of the proximal humerus usually occur after middle age and most of the

patients are osteoporotic, postmenopausal women.

Fracture usually follows a fall on the out-stretched arm – the type of injury which, in

younger people ,might cause dislocation of the shoulder. Sometimes, indeed, there is

both a fracture and a dislocation.

A b c d

X-rays of proximal humeral fractures

Classification is all very well, but x-rays are more difficult to

interpret than line drawings.

(a)

Two-part fracture.

(b)

Three-part fracture involving the neck and the

greater tuberosity.

(c)

Four-part fracture. (1=shaft of humerus; 2=head of humerus; 3=greater tuberosity;

4=lesser tuberosity).

(d)

X-ray showing fracture -dislocation of the shoulder.

Clinical features

Because the fracture is often firmly impacted, pain may not be severe. However, the

appearance of a large bruise on the upper part of the arm is suspicious. Signs of axillary

nerve or brachial plexus injury should be sought.

X-ray

In elderly patients there often appears to be a single, impacted fracture extending across

the surgical neck.

Neer’s classification (as shown above)when based on plain x-rays

criteria for displacement (distance >1 cm, angulation >45 degrees) help clarify the

pathoanatomy of the different fracture patterns.

The advent of three-dimensional CT reconstruction has helped to reduce the degree of

inter- and intra-observer error.

Treatment

Minimally displaced fractures, which comprise the vast majority. They need no

treatment apart from a week or two period of rest with the arm in a sling until the pain

subsides, and then gentle passive movements of the shoulder.

Displaced fractures need surgical intervention , while fracture- dislocation in elderly

osteoporotic patients(especially four-part), prosthetic replacement is recommended.

FRACTURED SHAFT OF HUMERUS

Mechanism of injury

A fall on the hand may twist the humerus, causing a spiral fracture. A fall on the elbow

with the arm abducted exerts a bending force, resulting in an oblique or transverse

fracture. A direct blow to the arm causes a fracture which is either transverse or

comminuted. Fracture of the shaft in an elderly patient may be due to a metastasis.

Clinical features

The arm is painful, bruised and swollen. It is important to test for radial nerve function

before and after treatment.

X-ray

The site of the fracture, its line (transverse, spiral or comminuted) and any displacement

are readily seen.

The possibility that the fracture may be pathological should be remembered.

Treatment

Fractures of the humerus heal readily. They require neither perfect reduction nor

immobilization; the weight of the arm with an external cast is usually enough to pull the

fragments into alignment. A ‘hanging cast’ is applied from shoulder to wrist with the

elbow flexed 90 degrees, and the forearm section is suspended by a sling around the

patient’s neck. This cast may be replaced after 2–3 weeks by a short(shoulder to elbow)

cast or a functional polypropylene brace which is worn for a further 6 weeks.

There are, nevertheless, some well defined indications for surgery:

(1)severe multiple injuries, (2) an open fracture,(3) segmental fractures,(4) displaced

intra-articular extension of the fracture,(5) a pathological fracture,(6) a ‘floating elbow’

(simultaneous unstable humeral and forearm fractures),(7) radial nerve palsy after

manipulation,(8) non-union,(9) problems with nursing care in a dependent person.

Complications

EARLY

Vascular injury If there are signs of vascular insufficiency in the limb, brachial artery

damage must be excluded.

Nerve injury Radial nerve palsy (wrist drop and paralysis of the metacarpophalangeal

extensors) may occur with shaft fractures, particularly oblique fracturesat the junction

of the middle and distal thirds of the bone (Holstein–Lewis fracture).

LATE

Delayed union and non-union Transverse fractures sometimes take months to unite,

especially if excessive traction has been used (a hanging cast must not be too heavy).

Joint stiffness Joint stiffness is common. It can be minimized by early activity.