1

Digestion & Absorption

BIOMEDICAL IMPORTANCE

Besides water, the diet must provide metabolic fuels (mainly

carbohydrates and lipids), protein (for growth and turnover of tissue

proteins), fiber (for roughage), minerals (elements with specific metabolic

functions), and vitamins and essential fatty acids (organic compounds

needed in small amounts for essential metabolic and physiologic

functions).

The polysaccharides, triacylglycerols, and proteins that make up the bulk

of the diet must be hydrolyzed to their constituent monosaccharides, fatty

acids, and amino acids, respectively, before absorption and utilization.

Minerals and vitamins must be released from the complex matrix of food

before they can be absorbed and utilized.

Digestion of Carbohydrates

:

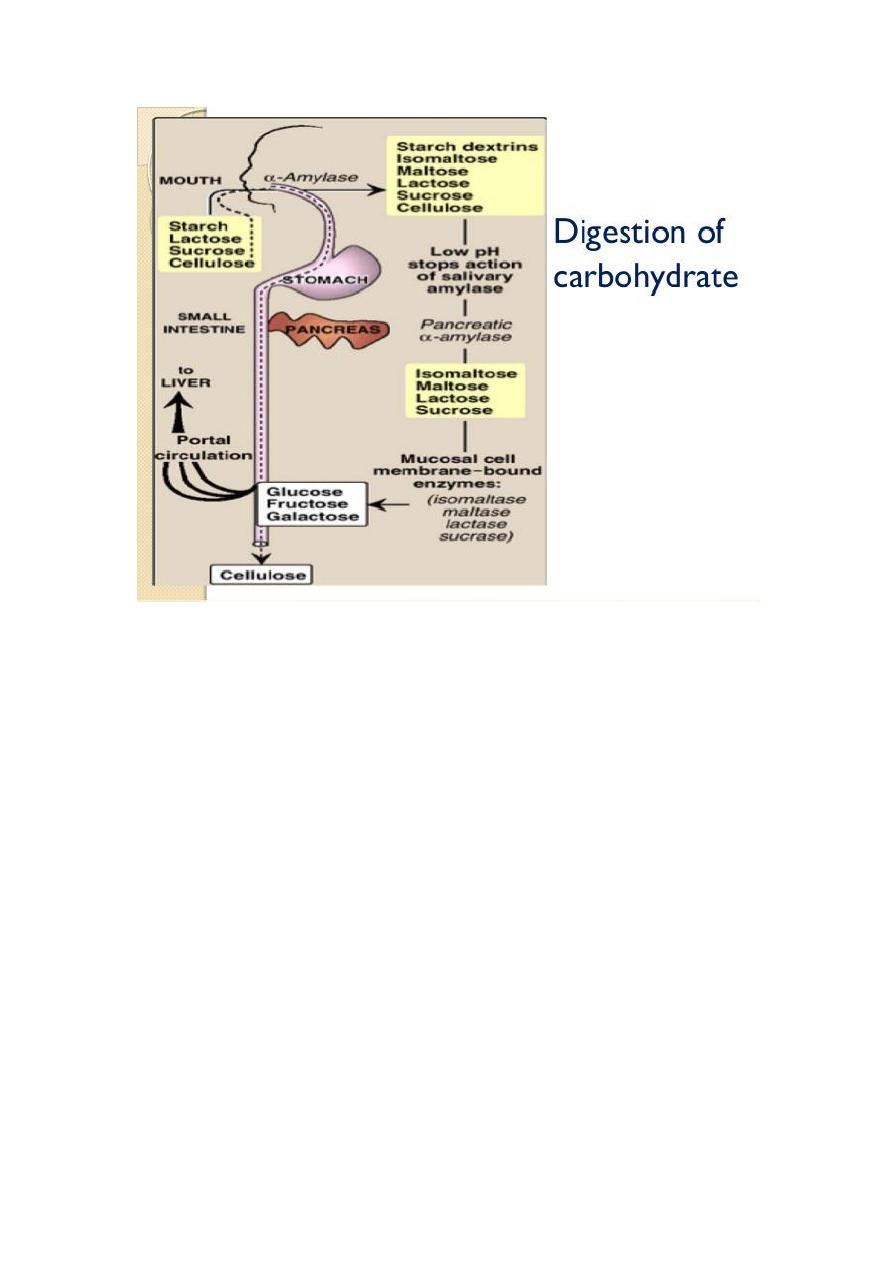

The principal sites of dietary carbohydrate digestion are the mouth and

intestinal lumen.

In the mouth:

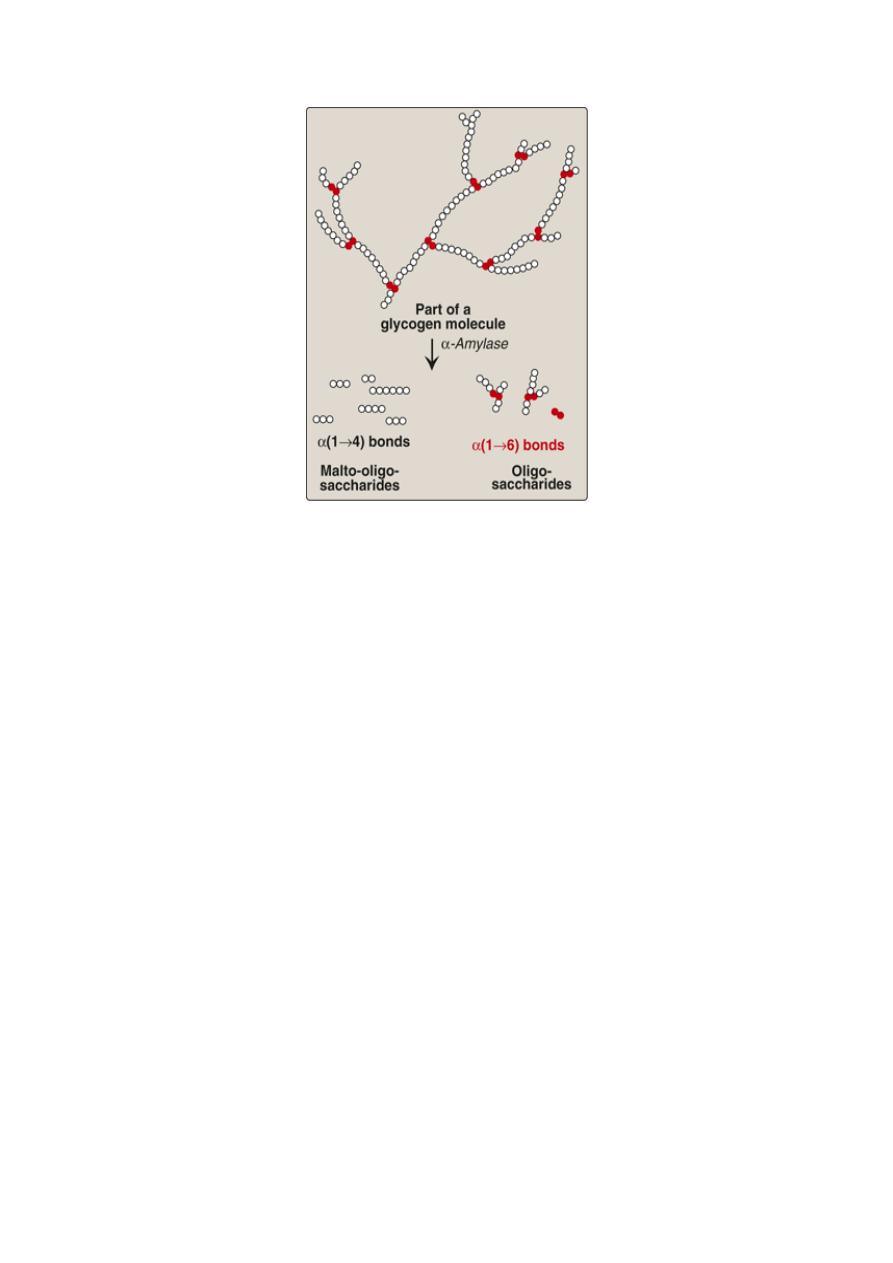

During mastication, salivary α-amylase acts briefly on

dietary starch and glycogen in a random manner, hydrolyzing some

α(1→4) bonds. Because branched amylopectin and glycogen also contain

α(1→6) bonds, which α-amylase cannot hydrolyze, the digest resulting

from its action contains a mixture of short, branched oligosaccharides or

dextrins.

2

Degradation of dietary glycogen by salivary or pancreatic α-amylase

In the stomach:

Carbohydrate digestion halts temporarily in the

stomach, because the high acidity inactivates the salivary α-amylase.

in the small intestine

:

When the acidic stomach contents reach the

small intestine, they are neutralized by bicarbonate secreted by the

pancreas, and pancreatic α-amylase continues the process of starch

digestion. The final digestive processes occur at the mucosal lining of the

upper jejunum, declining as they proceed down the small intestine, and

include the action of several disaccharidases and oligosaccharidases.

For example, - isomaltase cleaves the α(1→6) bond in isomaltose .

- maltase cleaves maltose, both producing glucose.

- sucrase cleaves sucrose producing glucose and fructose.

- lactase (β-galactosidase) cleaves lactose producing galactose and

glucose. These enzymes are secreted through, and remain

associated with, the luminal side of the brush border membranes of

the intestinal mucosal cells.

3

Absorption of monosaccharides

The duodenum and upper jejunum absorb the bulk of the dietary sugars.

Insulin is not required for the uptake of glucose by intestinal cells.

However, different sugars have different mechanisms of absorption.

-

galactose and glucose are transported into the mucosal cells by an

active, energy-requiring process that requires a concurrent uptake

of sodium ions; the transport protein is the sodium-dependent

glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT-1).

-

Fructose uptake requires a sodium-independent monosaccharide

transporter (GLUT-5) for its absorption.

4

Abnormal degradation of disaccharides

1. Digestive enzyme deficiencies:

Causes:

a. Hereditary deficiencies of disaccharidases.

b. Malnutrition.

c. drugs that injure the mucosa of the small intestine.

d. normal individuals with severe diarrhea lead to brush border

enzymes are rapidly lost, causing a temporary, acquired enzyme

deficiency. Thus, patients suffering or recovering from such a

disorder cannot drink or eat significant amounts of dairy

products or sucrose without exacerbating the diarrhea.

2.

Lactose intolerance

:

More than three quarters of the world's adults are lactose intolerant.

This is particularly manifested in certain races. For example, up to

ninety percent of adults of African or Asian descent are lactase-

deficient and, therefore, are less able to metabolize lactose than

individuals of Northern European origin.

The mechanism: by which this age-dependent loss of the enzyme

occurs is not clear, but it is determined genetically and represents a

reduction in the amount of enzyme protein rather than a modified

inactive enzyme.

-

Treatment:

for this disorder is to reduce consumption of milk while eating

yogurts and cheeses, as well as green vegetables such as broccoli,

to ensure adequate calcium intake; to use lactase-treated products;

or to take lactase in pill form prior to eating.

5

Abnormal lactose metabolism

3.

Isomaltase-sucrase deficiency:

This enzyme deficiency results in

an intolerance of ingested sucrose.

-

Treatment :

includes the withholding of dietary sucrose, and

enzyme replacement therapy.

Diagnosis:

1. Identification of a specific enzyme deficiency can be obtained

by performing oral tolerance tests with the individual

disaccharides.

2. Measurement of hydrogen gas in the breath is a reliable test for

determining the amount of ingested carbohydrate not absorbed

by the body, but which is metabolized instead by the intestinal

flora.

6

DIGESTION & ABSORPTION OF LIPIDS:

The major lipids in the diet are triacylglycerols and,

the remainder of

the dietary lipids consists primarily of cholesterol, cholesteryl esters,

phospholipids, and unesterified (“free”) fatty acids.

In the stomach:

The digestion of lipids begins in the stomach, catalyzed

by an acid-stable lipase that originates from glands at the back of the

tongue (lingual lipase). TAG molecules, particularly those containing

fatty acids of short- or medium-chain length (less than 12 carbons, such

as are found in milk fat), are the primary target of this enzyme. These

same TAGs are also degraded by a separate gastric lipase, secreted by the

gastric mucosa. Both enzymes are relatively acid-stable, with pH

optimums of pH 4 to pH 6. These “acid lipases” play a particularly

important role in lipid digestion in neonates, for whom milk fat is the

primary source of calories.

In the small intestine:

emulsification of dietary lipids occurs in the

duodenum. Emulsification increases the surface area of the hydrophobic

lipid droplets so that the digestive enzymes, which work at the interface

of the droplet and the surrounding aqueous solution, can act effectively.

1.

TAG degradation

pancreatic enzymes:

- pancreatic lipase :act on TAG molecules because they are too large

to be taken up efficiently by the mucosal cells of the intestinal villi.

which preferentially removes the fatty acids at carbons 1 and 3.

- Colipase: also secreted by the pancreas, binds the lipase at a ratio

of 1:1, and anchors it at the lipid-aqueous interface.

N.B: Orlistat, an antiobesity drug, inhibits gastric and pancreatic

lipases, thereby decreasing fat absorption, resulting in loss of weight.

7

2. Cholesteryl ester degradation:

Most dietary cholesterol is present in the free (nonesterified) form,

with 10–15% present in the esterified form. Cholesteryl esters are

hydrolyzed by pancreatic cholesteryl ester hydrolase (cholesterol

esterase), which produces cholesterol plus free fatty acids.

Cholesteryl ester hydrolase activity is greatly increased in the

presence of bile salts.

3. Phospholipid degradation:

Pancreatic juice is rich in the proenzyme of phospholipase A

2

that,

like procolipase, is activated by trypsin and, like cholesteryl ester

hydrolase, requires bile salts for optimum activity. Phospholipase

A

2

removes one fatty acid from carbon 2 of a phospholipid, leaving

a lysophospholipid. The remaining fatty acid at carbon 1 can be

removed by lysophospholipase, leaving a glycerylphosphoryl base.

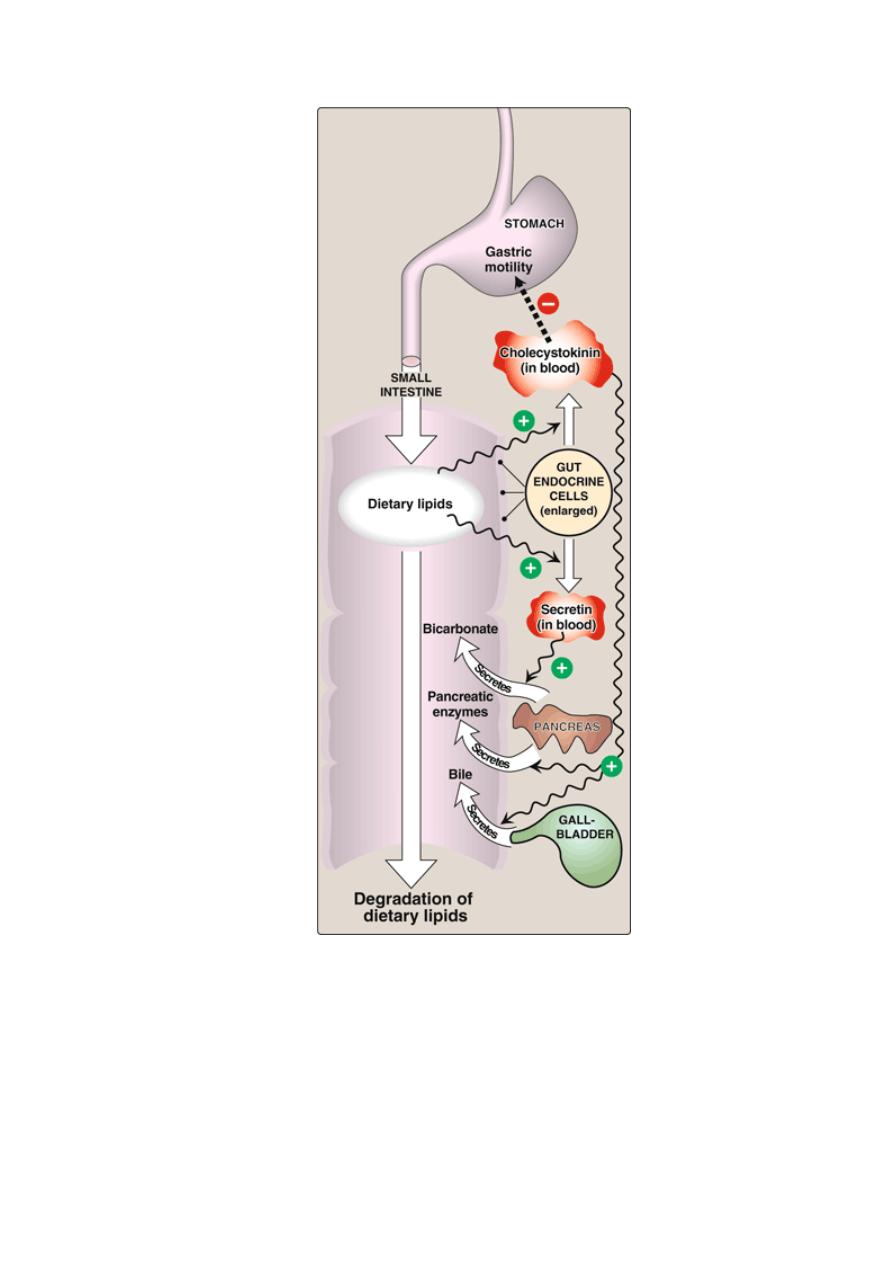

Control of lipid digestion:

1. Cholecystokinin (CCK, formerly called pancreozymin):

a small

peptide hormone is produced by the Cells in the mucosa of the

jejunum and lower duodenum in response to the presence of lipids

and partially digested proteins entering these regions of the upper

small intestine. CCK acts on the gallbladder (causing it to contract

and release bile—a mixture of bile salts, phospholipids, and free

cholesterol), and on the exocrine cells of the pancreas (causing

them to release digestive enzymes). It also decreases gastric

motility, resulting in a slower release of gastric contents into the

small intestine.

2. Secretin,

in response to the low pH of the chyme entering the

intestine. Secretin causes the pancreas and the liver to release a

watery solution rich in bicarbonate that helps neutralize the pH of

the intestinal contents, bringing them to the appropriate pH for

digestive activity by pancreatic enzymes.

8

Hormonal control of lipid digestion in the small intestine.

9

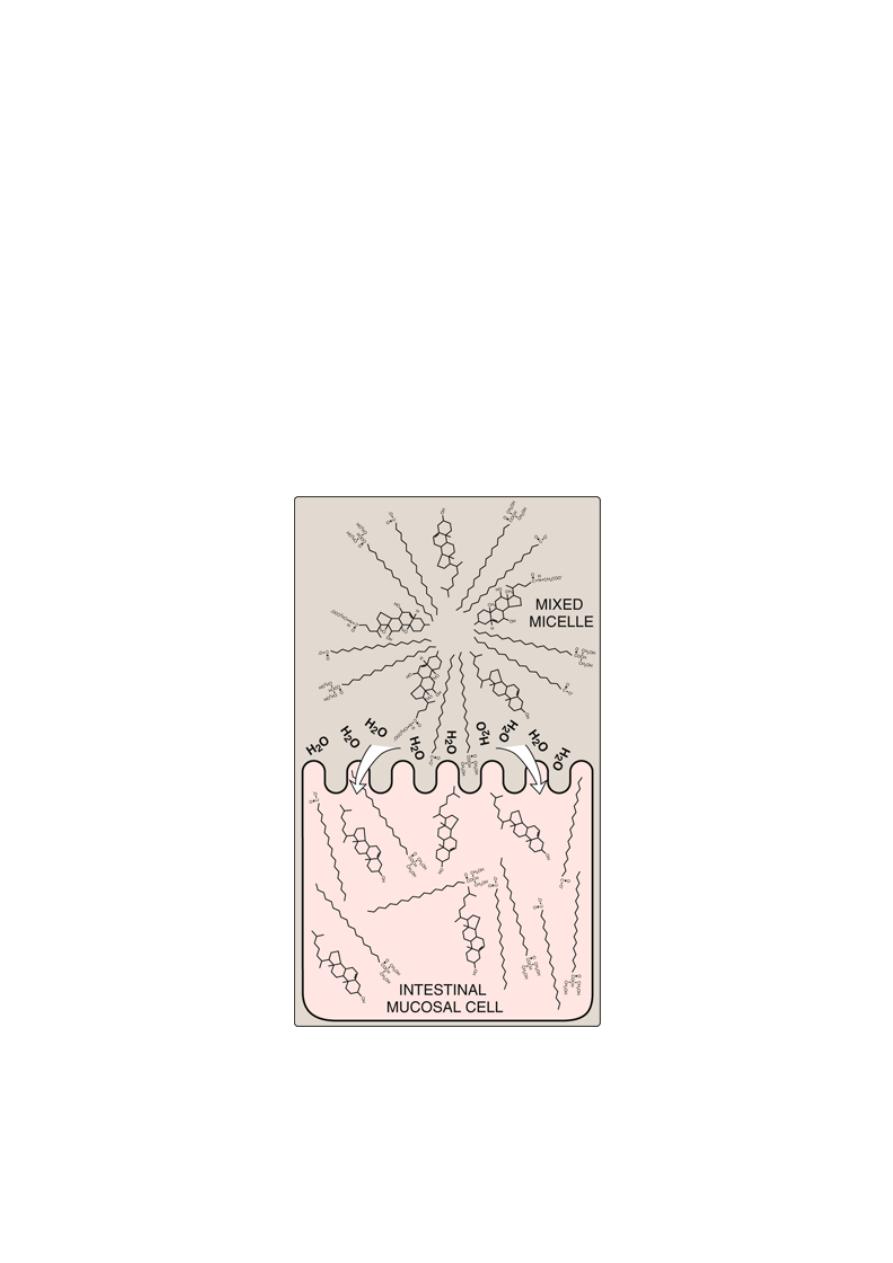

Absorption of lipids by intestinal mucosal cells (enterocytes)

Free fatty acids, free cholesterol, and 2-monoacylglycerol are the primary

products of lipid digestion in the jejunum. These, plus bile salts and fat-

soluble vitamins, form mixed micelles—disk-shaped clusters of

amphipathic lipids that coalesce with their hydrophobic groups on the

inside and their hydrophilic groups on the outside. Mixed micelles are,

therefore, soluble in the aqueous environment of the intestinal lumen.

These particles approach the primary site of lipid absorption, the brush

border membrane of the enterocytes (mucosal cell). This membrane is

separated from the liquid contents of the intestinal lumen by an unstirred

water layer that mixes poorly with the bulk fluid. The hydrophilic surface

of the micelles facilitates the transport of the hydrophobic lipids through

the unstirred water layer to the brush border membrane where they are

absorbed.

Absorption of lipids contained in a mixed micelle by an intestinal

mucosal cell.

10

Resynthesis of TAG and cholesteryl esters

The mixture of lipids absorbed by the enterocytes migrates to the

endoplasmic reticulum where biosynthesis of complex lipids takes place.

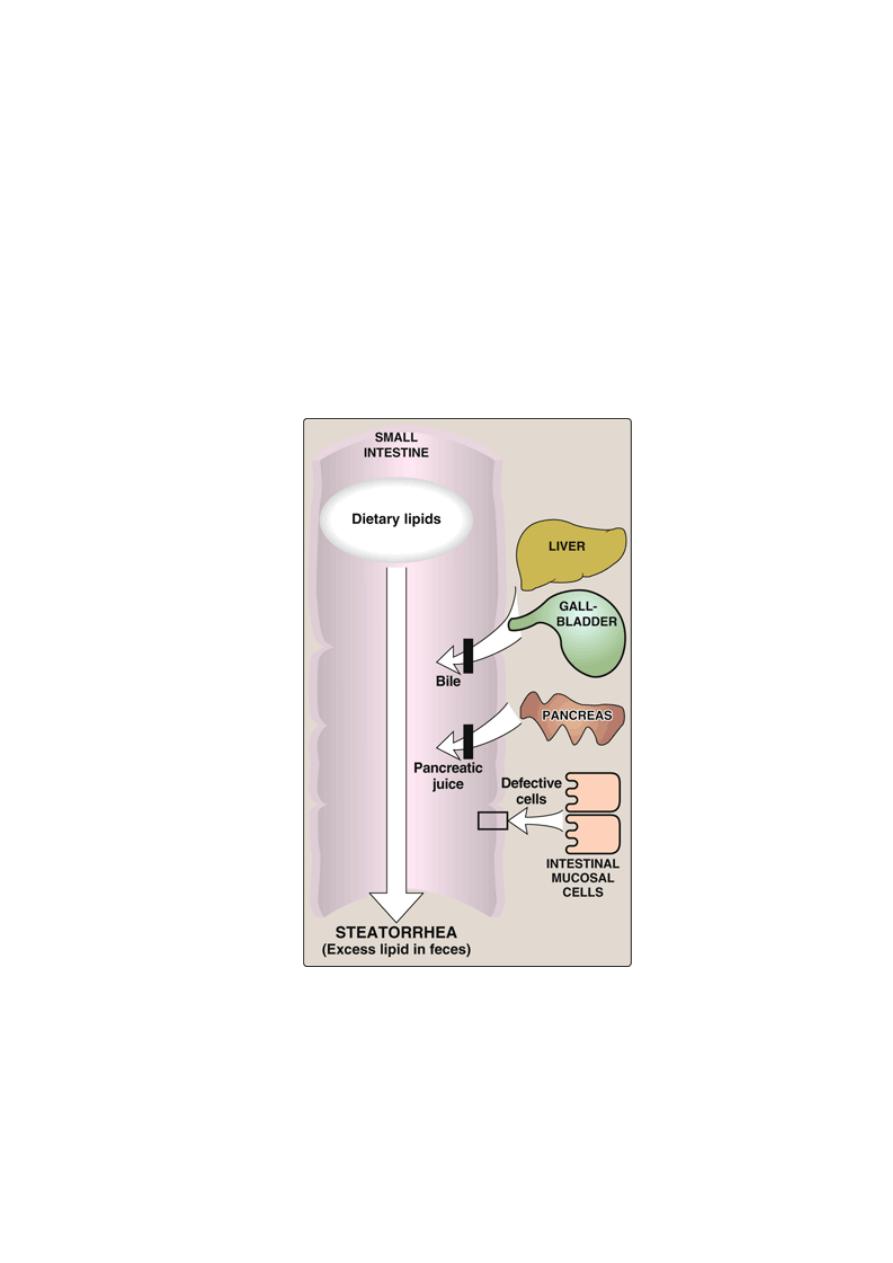

Lipid malabsorption

Lipid malabsorption, resulting in increased lipid (including the fat-soluble

vitamins A, D, E, and K, and essential fatty acids) in the feces (that is,

steatorrhea), can be caused by disturbances in lipid digestion and/or

absorption . Such disturbances can result from several conditions,

including CF (causing poor digestion) and shortened bowel (causing

decreased absorption).

Possible causes of steatorrhea

11

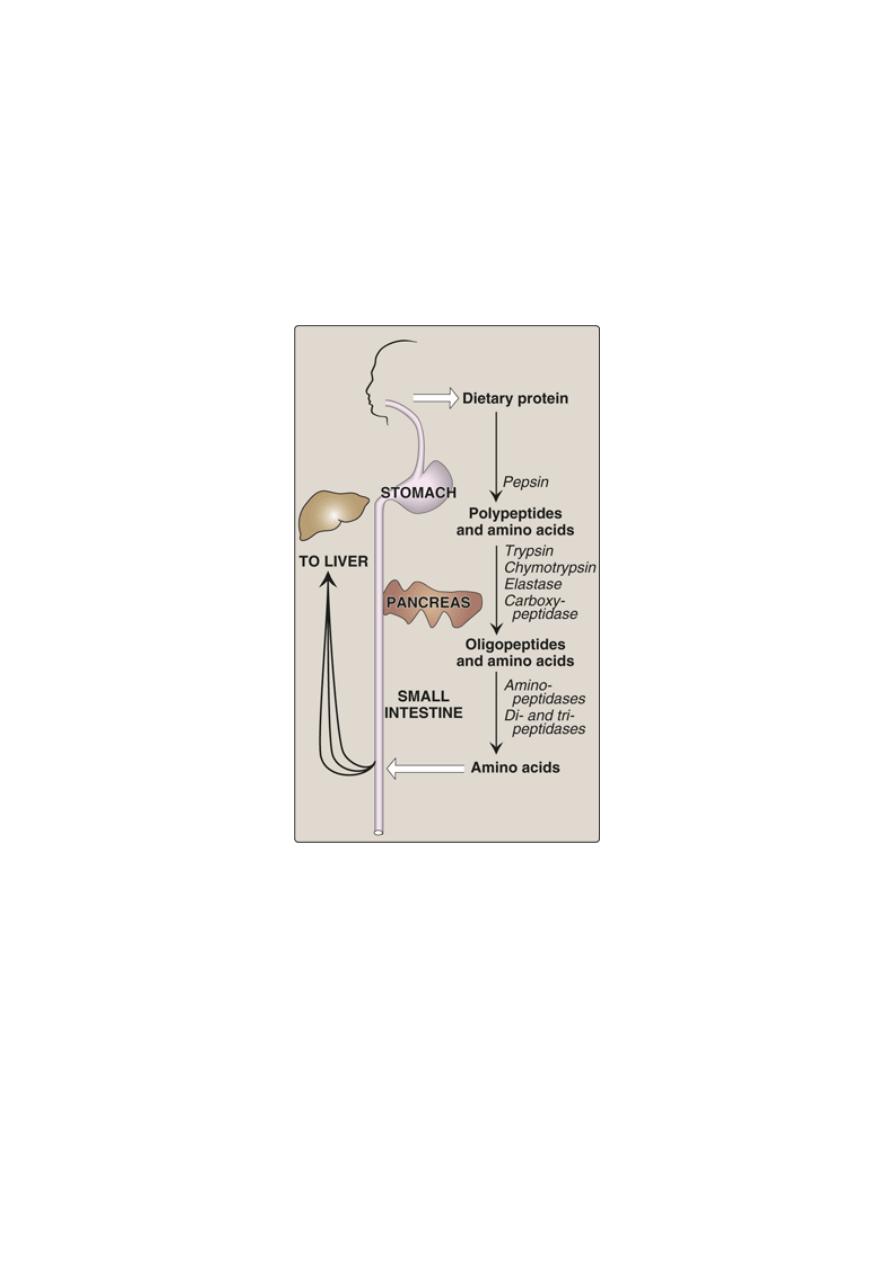

Digestion of Dietary Proteins

Most of the nitrogen in the diet is consumed in the form of protein,

Proteins are generally too large to be absorbed by the intestine. They

must, therefore, be hydrolyzed to yield their constituent amino acids,

which can be absorbed. Proteolytic enzymes responsible for degrading

proteins are produced by three different organs: the stomach, the

pancreas, and the small intestine .

Digestion of dietary proteins by the proteolytic enzymes of the

gastrointestinal tract.

12

Digestion of proteins by gastric secretion

The digestion of proteins begins in the stomach, which secretes gastric

juice—a unique solution containing hydrochloric acid and the

proenzyme, pepsinogen.

1. Hydrochloric acid:

Stomach acid is too dilute (pH 2–3) to

hydrolyze proteins. The acid functions instead to kill some bacteria

and to denature proteins, thus making them more susceptible to

subsequent hydrolysis by proteases.

2. Pepsin:

This acid-stable endopeptidase is secreted by the serous

cells of the stomach as an inactive zymogen (or proenzyme),

pepsinogen. Pepsinogen is activated to pepsin, either by HCl, or

autocatalytically by other pepsin molecules that have already been

activated. Pepsin releases peptides and a few free amino acids from

dietary proteins.

Digestion of proteins by pancreatic enzymes

On entering the small intestine, large polypeptides produced in the

stomach by the action of pepsin are further cleaved to oligopeptides and

amino acids by a group of pancreatic proteases.

Release of zymogens:

The release and activation of the pancreatic

zymogens is mediated by the secretion of cholecystokinin and

secretin, two polypeptide hormones of the digestive tract.

Enteropeptidase

(formerly called enterokinase)— an enzyme

synthesized by and present on the luminal surface of intestinal

mucosal cells of the brush border membrane—converts the

pancreatic zymogen trypsinogen to trypsin. Trypsin subsequently

converts other trypsinogen molecules to trypsin by cleaving a

limited number of specific peptide bonds in the zymogen.

Enteropeptidase thus unleashes a cascade of proteolytic activity,

because trypsin is the common activator of all the pancreatic

zymogens.

- Celiac disease

(celiac sprue) is a disease of malabsorption

resulting from immune-mediated damage to the small intestine in

response to ingestion of gluten, a protein found in wheat and other

grains.

13

Digestion of oligopeptides by enzymes of the small intestine

The luminal surface of the intestine contains aminopeptidase—an

exopeptidase that repeatedly cleaves the N-terminal residue from

oligopeptides to produce free amino acids and smaller peptides.

Absorption of amino acids and dipeptides

Free amino acids are taken into the enterocytes up by a Na

+

-linked

secondary transport system. Di- and tripeptides, however, are taken up by

a H

+

-linked transport system. There, the peptides are hydrolyzed in the

cytosol to amino acids before being released into the portal system. Thus,

only free amino acids are found in the portal vein after a meal containing

protein. These amino acids are either metabolized by the liver or released

into the general circulation.

DIGESTION & ABSORPTION OF VITAMINS & MINERALS

Vitamins and minerals are released from food during digestion—though

this is not complete—and the availability of vitamins and minerals

depends on the type of food and, especially for minerals, the presence of

chelating compounds.

The fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed in the lipid micelles that result

from fat digestion; water-soluble vitamins and most mineral salts are

absorbed from the small intestine either by active transport or by carrier-

mediated diffusion followed by binding to intracellular binding proteins

to achieve concentration upon uptake.

Vitamin B12 absorption requires a specific transport protein, intrinsic

factor; calcium absorption is dependent on vitamin D; zinc absorption

probably requires a zinc-binding ligand secreted by the exocrine

pancreas; and the absorption of iron is limited.

Calcium Absorption Is Dependent on Vitamin D

In addition to its role in regulating calcium homeostasis, vitamin D is

required for the intestinal absorption of calcium. Synthesis of the

intracellular calciumbinding protein, calbindin, required for calcium

absorption, is induced by vitamin D, which also affects the permeability

of the mucosal cells to calcium, an effect that is rapid and independent of

protein synthesis. Phytic acid (inositol hexaphosphate) in cereals binds

calcium in the intestinal lumen, preventing its absorption.

14

Other minerals, including zinc, are also chelated by phytate. This is

mainly a problem among people who consume large amounts of

unleavened whole wheat products; yeast contains an enzyme, phytase,

which dephosphorylates phytate, so rendering it inactive.

High concentrations of fatty acids in the intestinal lumen—as a result of

impaired fat absorption—can also reduce calcium absorption by forming

insoluble calcium salts; a high intake of oxalate can sometimes cause

deficiency, since calcium oxalate is insoluble.

Iron Absorption

Although iron deficiency is a common problem, about10% of the

population are genetically at risk of iron overload (hemochromatosis).

Absorption of iron is strictly regulated. Inorganic iron is accumulated

in intestinal mucosal cells bound to an intracellular protein, ferritin.

Once the ferritin in the cell is saturated with iron, no more can enter. Iron

can only leave the mucosal cell if there is transferrin in plasma to bind

to. Once transferrin is saturated with iron, any that has accumulated in

the mucosal cells will be lost when the cells are shed. As a result of this

mucosal barrier,

only about 10% of dietary iron is normally absorbed and only 1–5% from

many plant foods.

Inorganic iron is absorbed only in the Fe

2+

(reduced) state, and for that

reason the presence of reducing agents will enhance absorption. The most

effective compound is vitamin C, and while intakes of 40–60 mg of

vitamin C per day are more than adequate to meet requirements, an intake

of 25–50 mg per meal will enhance iron absorption, especially when iron

salts are used to treat iron deficiency anemia. Ethanol and fructose also

enhance iron absorption. Heme iron from meat is absorbed separately and

is considerably more available than inorganic iron. However, the

absorption of both inorganic and heme iron is impaired by calcium—a

glass of milk with a meal significantly reduces availability.