1

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم

Lecture -2- Medical Physiology (GIT system)

2

nd

stage Dr. Noor Jawad

Autonomic Control of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Objectives of our lecture:

1. What is the effect of sympathetic and parasympathetic

stimulation on GIT?

2. Hormonal control of GIT?

Parasympathetic Stimulation Increases Activity of the

Enteric Nervous System.

The parasympathetic supply to the gut is divided into cranial and

sacral divisions. Except for a few parasympathetic fibers to the

mouth and pharyngeal regions of the alimentary tract, the cranial

parasympathetic nerve fibers are almost entirely in the vagus nerves.

These fibers provide extensive innervation to the esophagus,

stomach, and pancreas and somewhat less to the intestines down

through the first half of the large intestine. The sacral

parasympathetics originate in the second, third, and fourth sacral

segments of the spinal cord and pass through the pelvic nerves to the

distal half of the large intestine and all the way to the anus.

2

The sigmoidal, rectal, and anal regions are considerably better

supplied with parasympathetic fibers than are the other intestinal

areas.

The postganglionic neurons of the gastrointestinal parasympathetic

system are located mainly in the myenteric and submucosal

plexuses.

Stimulation of these parasympathetic nerves causes general increase

in activity of the entire enteric nervous system, which in turn

enhances activity of most gastrointestinal functions.

Sympathetic Stimulation Usually Inhibits Gastrointestinal

Tract Activity.

The sympathetic fibers to the gastrointestinal tract originate in the

spinal cord between segments T5 and L2. Most of the preganglionic

fibers that innervate the gut, after leaving the cord, enter the

sympathetic chains that lie lateral to the spinal column, and many of

these fibers then pass on through the chains to outlying ganglia such

as to the celiac ganglion and various mesenteric ganglia. Most of the

postganglionic sympathetic neuron bodies are in these ganglia, and

postganglionic fibers then spread through postganglionic

sympathetic nerves to all parts of the gut.

The sympathetics innervate essentially all of the gastrointestinal

tract, rather than being more extensive nearest the oral cavity and

3

anus, as is true of the parasympathetics. The sympathetic nerve

endings secrete mainly norepinephrine. In general, stimulation of

the sympathetic nervous system inhibits activity of the

gastrointestinal tract, causing many effects opposite to those of the

parasympathetic system. It exerts its effects in two ways: (1) to a

slight extent by direct effect of secreted norepinephrine to inhibit

intestinal tract smooth muscle (except the mucosal muscle, which it

excites) and (2) to a major extent by an inhibitory effect of

norepinephrine on the neurons of the entire enteric nervous system.

Strong stimulation of the sympathetic system can inhibit motor

movements of the gut so greatly that this can literally block

movement of food through the gastrointestinal tract.

Afferent Sensory Nerve Fibers From the Gut

Many afferent sensory nerve fibers innervate the gut. Some of the

nerve fibers have their cell bodies in the enteric nervous system and

some have them in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. These

sensory nerves can be stimulated by (1) irritation of the gut mucosa,

(2) excessive distention of the gut, or (3) the presence of specific

chemical substances in the gut. Signals transmitted through the

fibers can then cause excitation or, under other conditions, inhibition

of intestinal movements or intestinal secretion.

4

In addition, other sensory signals from the gut go all the way to

multiple areas of the spinal cord and even to the brain stem. For

example, 80 percent of the nerve fibers in the vagus nerves are

afferent rather than efferent. These afferent fibers transmit sensory

signals from the gastrointestinal tract into the brain medulla which,

in turn, initiates vagal reflex signals that return to the gastrointestinal

tract to control many of its functions.

Gastrointestinal Reflexes

The anatomical arrangement of the enteric nervous system and its

connections with the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems

support three types of gastrointestinal reflexes that are essential to

gastrointestinal control:

1. local reflexes: Reflexes that are integrated entirely within the gut

wall enteric nervous system. These reflexes include those that

control much gastrointestinal secretion, peristalsis, mixing

contractions, local inhibitory effects, and so forth.

2. Short reflexes : Reflexes from the gut to the prevertebral

sympathetic ganglia and then back to the gastrointestinal tract.

These reflexes transmit signals long distances to other areas of the

gastrointestinal tract, such as signals from the stomach to cause

evacuation of the colon (the gastrocolic reflex), signals from the

colon and small intestine to inhibit stomach motility and stomach

5

secretion (the enterogastric reflexes), and reflexes from the colon to

inhibit emptying of ileal contents into the colon (the colonoileal

reflex).

3. long reflexes: Reflexes from the gut to the spinal cord or brain

stem and then back to the gastrointestinal tract. These reflexes

include especially (1) reflexes from the stomach and duodenum to

the brain stem and back to the stomach—by way of the vagus

nerves— to control gastric motor and secretory activity; (2) pain

reflexes that cause general inhibition of the entire gastrointestinal

tract; and (3) defecation reflexes that travel from the colon and

rectum to the spinal cord and back again to produce the powerful

colonic, rectal, and abdominal contractions required for defecation

(the defecation reflexes)

HORMONAL

CONTROL

OF

GASTROINTESTINAL

MOTILITY

The gastrointestinal hormones are released into the portal circulation

and exert physiological actions on target cells with specific

receptors for the hormone. The effects of the hormones persist even

after all nervous connections between the site of release and the site

of action have been severed.. Most of these same hormones also

affect motility in some parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Although

the motility effects are usually less important than the secretory

6

effects of the hormones, some of the more important motility effects

are described in the following paragraphs.

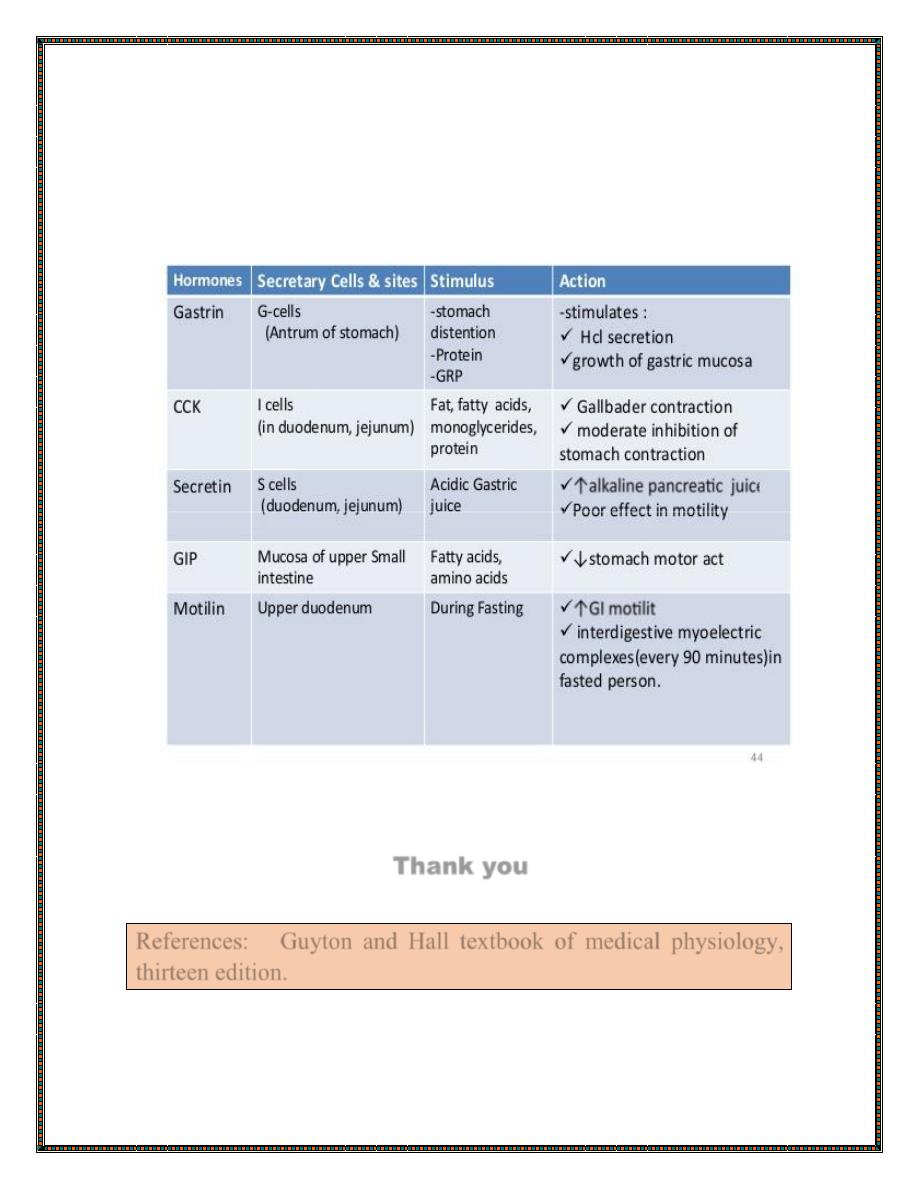

Gastrin is secreted by the “G” cells of the antrum of the stomach in

response to stimuli associated with ingestion of a meal, such as

distention of the stomach, the products of proteins, and gastrin-

releasing peptide, which is released by the nerves of the gastric

mucosa during vagal stimulation. The primary actions of gastrin are

(1) stimulation of gastric acid secretion and (2) stimulation of

growth of the gastric mucosa.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is secreted by “I” cells in the mucosa of

the duodenum and jejunum mainly in response to digestive products

of fat, fatty acids, and monoglycerides in the intestinal contents.

This hormone strongly contracts the gallbladder, expelling bile into

the small intestine, where the bile, in turn, plays important roles in

emulsifying fatty substances and allowing them to be digested and

absorbed. CCK also inhibits stomach contraction moderately.

Therefore, at the same time that this hormone causes emptying of

the gallbladder, it also slows the emptying of food from the stomach

to give adequate time for digestion of the fats in the upper intestinal

tract. CCK also inhibits appetite to prevent overeating during meals

by stimulating sensory afferent nerve fibers in the duodenum; these

fibers, in turn, send signals by way of the vagus nerve to inhibit

feeding centers in the brain .

7

Secretin, the first gastrointestinal hormone discovered, is secreted

by the “S” cells in the mucosa of the duodenum in response to acidic

gastric juice emptying into the duodenum from the pylorus of the

stomach. Secretin has a mild effect on motility of the gastrointestinal

tract and acts to promote pancreatic secretion of bicarbonate, which

in turn helps to neutralize the acid in the small intestine.

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (also called gastric

inhibitory peptide [GIP]) is secreted by the mucosa of the upper

small intestine, mainly in response to fatty acids and amino acids

but to a lesser extent in response to carbohydrate. It has a mild effect

in decreasing motor activity of the stomach and therefore slows

emptying of gastric contents into the duodenum when the upper

small intestine is already overloaded with food product Glucose-

dependent insulinotropic peptide, at blood levels even lower than

those needed to inhibit gastric motility, also stimulates insulin

secretion.

Motilin is secreted by the stomach and upper duodenum during

fasting, and the only known function of this hormone is to increase

gastrointestinal motility. Motilin is released cyclically and

stimulates waves of gastrointestinal motility called interdigestive

myoelectric complexes that move through the stomach and small

intestine every 90 minutes in a person who has fasted. Motilin

8

secretion is inhibited after ingestion of food by mechanisms that are

not fully understood.

Thank you

References: Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology,

thirteen edition.