ANORECTAL ABSCESSES

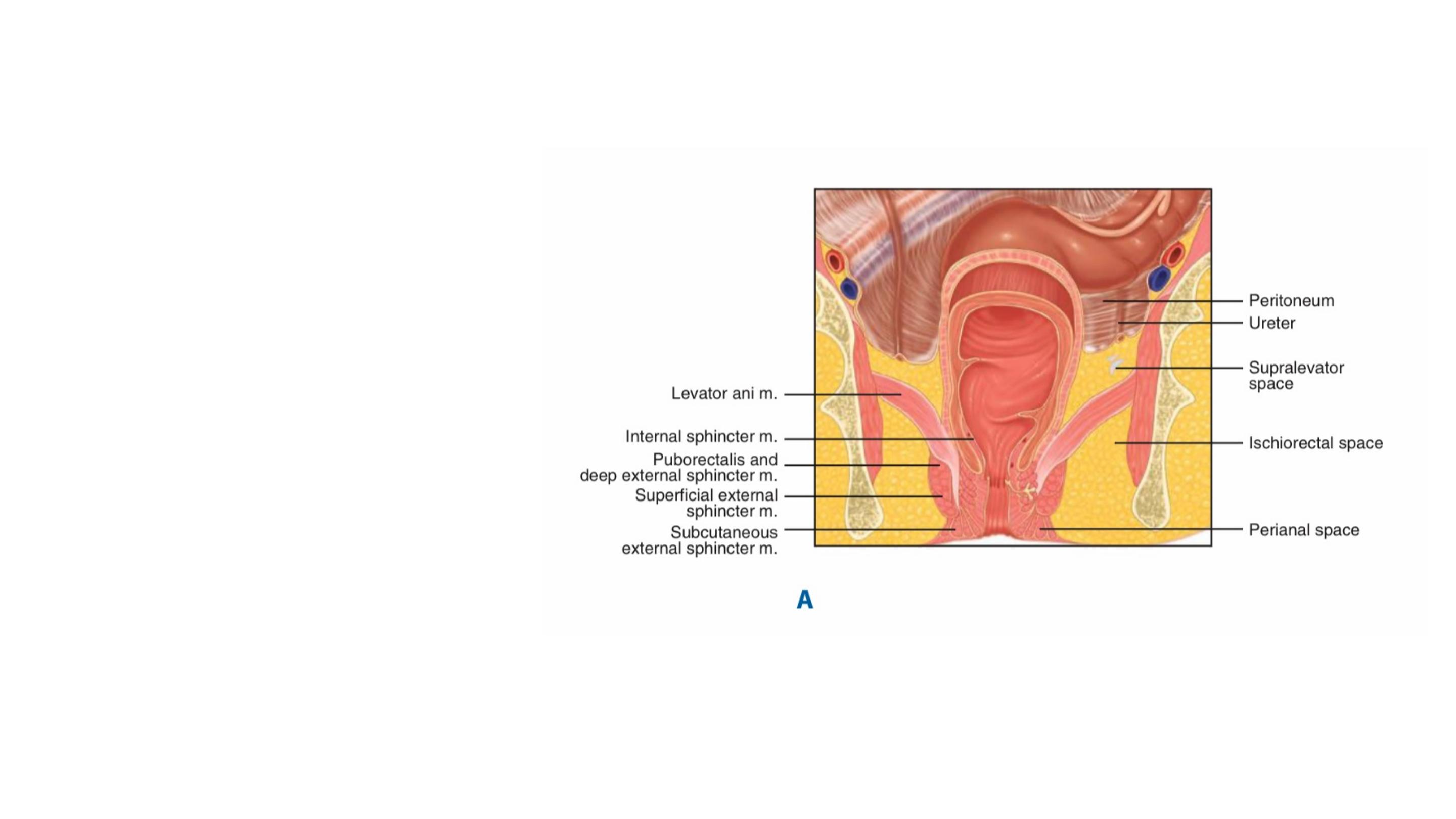

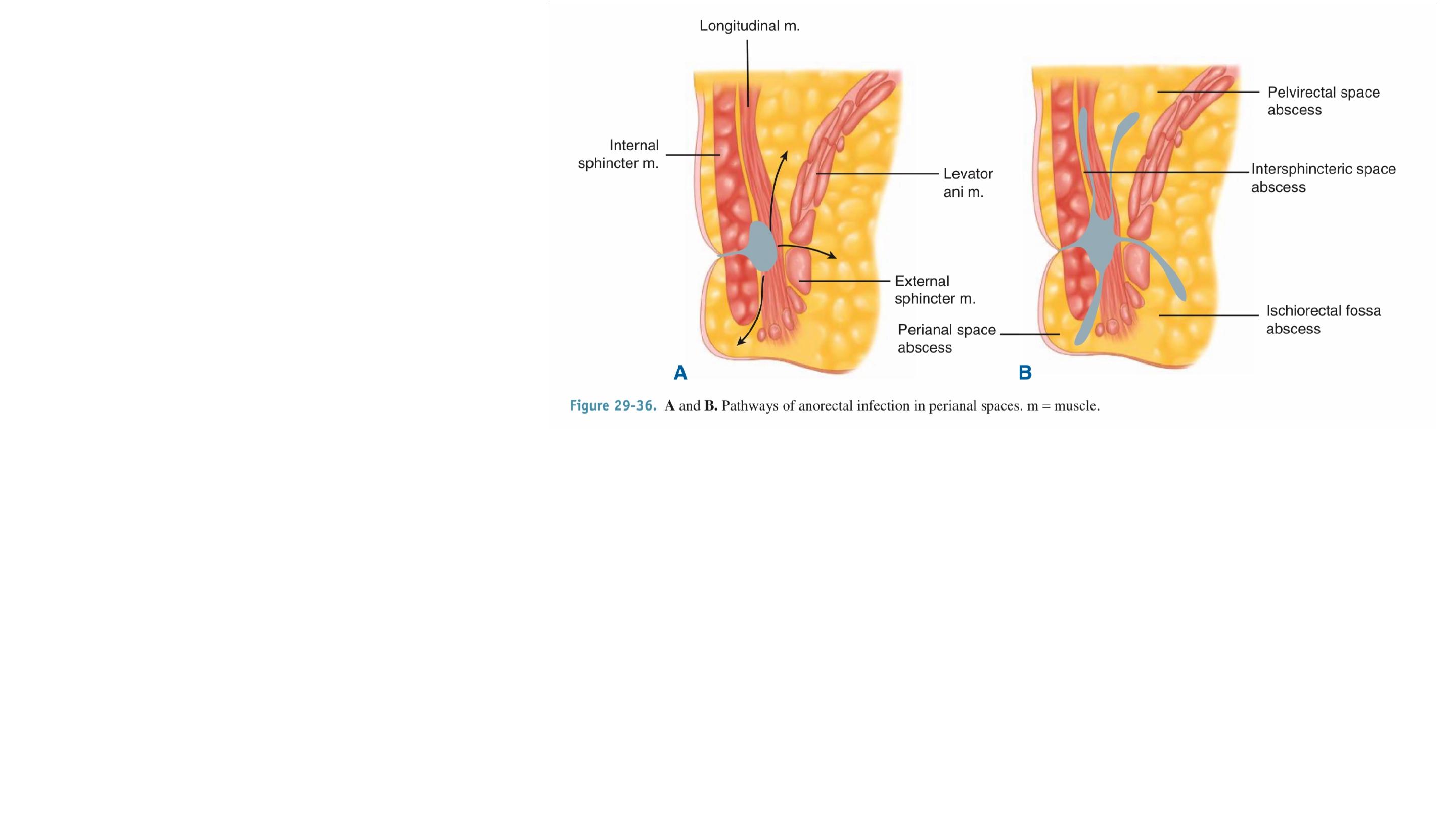

Infection of an anal gland results in the formation of an abscess that

enlarges and spreads along one of several planes in the perianal and

perirectal spaces.

The majority of anorectal suppurative disease results from infections of the

anal glands (cryptoglandular infection) found in the intersphincteric plane.

A perianal abscess is the

most common manifestation

and appears as a painful

swelling at the anal verge.

Spread through the external

sphincter below the level of

the puborectalis produces an

ischiorectal abscess.

Pelvic and supralevator abscesses are uncommon and may result from

extension of an intersphincteric or ischiorectal abscess upward or extension of

an intraperitoneal abscess downward

Intersphincteric abscesses occur in the inter- sphincteric space and are

notoriously difficult to diagnose, often requiring an examination under

anesthesia.

Sepsis unrelated to anal gland infection may occur in :

Submucosal abscess (following haemorrhoidal sclerotherapy, which

usually resolve spontaneously)

Mucocutaneous or marginal abscess (infected haematoma)

Ischiorectal abscess (foreign body, trauma, deep skin-related) and

pelvirectal supralevator sepsis originating in pelvic disease.

Underlying rectal disease, such as neoplasm and particularly

Crohn’s disease, may be the cause.

Patients with generalised disorders, such as diabetes and acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), may present with an anorectal

abscess.

Usually produces a painful, throbbing swelling in the anal region.

The patient often has swinging pyrexia

Subdivided according to anatomical site into perianal,

ischiorectal, submucous and pelvirectal

Underlying conditions include fistula-in-ano (most common),

Crohn’s disease, diabetes, immunosuppression

Always look for a potential underlying problem

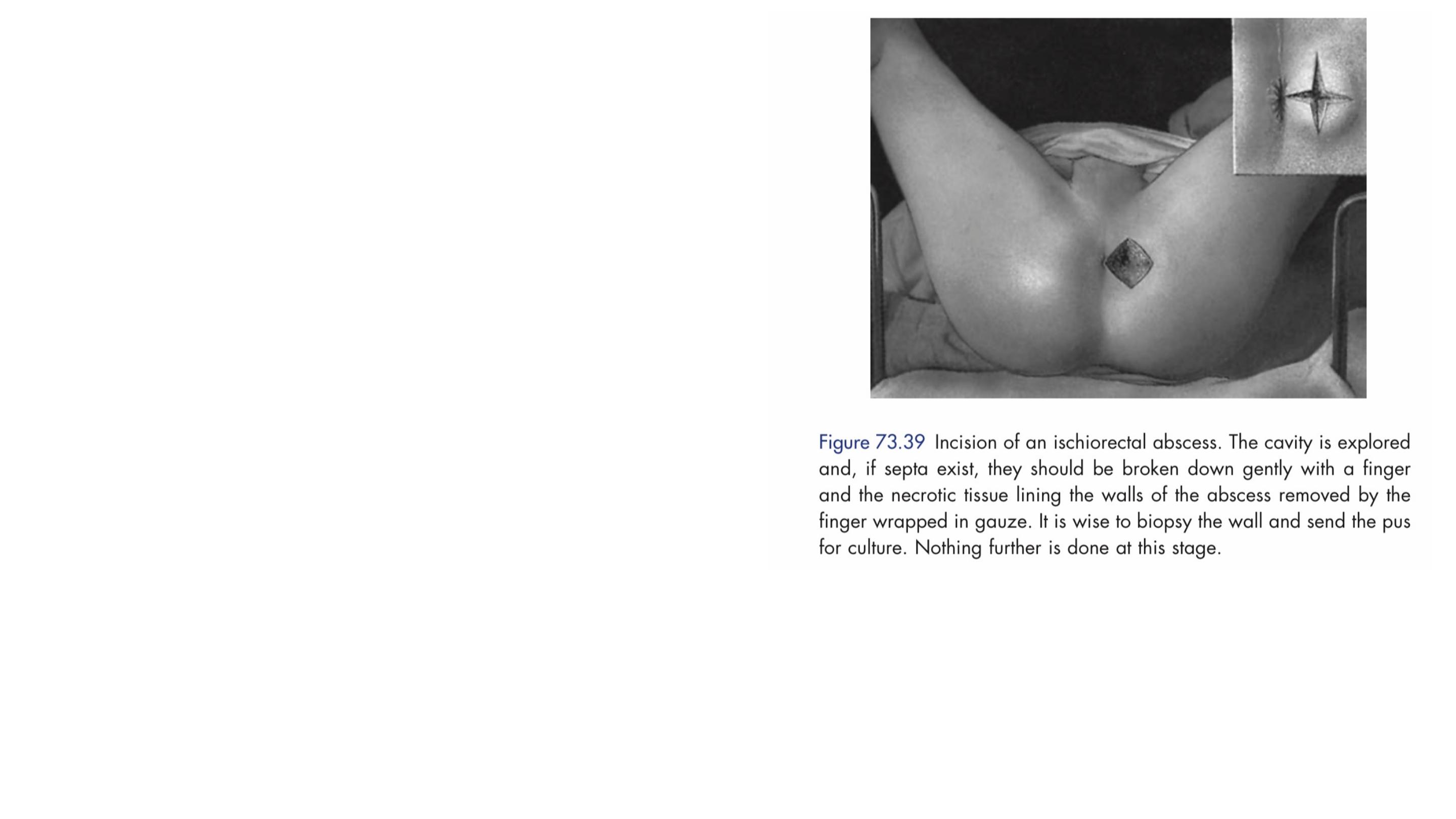

Management of acute anorectal sepsis is

primarily surgical, including careful

examination under anaesthesia,

sigmoidoscopy and proctoscopy, and

adequate drainage of the pus.

Pus is sent for microbiological

culture and tissue from the wall is

sent for histological appraisal to

exclude specific causes.

If the pus subsequently cultures skin-type organisms, there will be no

underlying fistula and the patient can be reassured. If gut flora are cultured, it

is likely, but not inevitable, that there is an underlying fistula.

FISTULA-IN-ANO

Is a chronic abnormal communication, usually lined to some degree by

granulation tissue, which runs outwards from the anorectal lumen (the

internal opening) to an external opening on the skin of the perineum or

buttock (or rarely, in women, to the vagina).

May be associated with underlying disease, such as tuberculosis ,

Crohn’s disease or malignancy.

Drainage of an anorectal abscess results in cure for about 50% of

patients. The remaining 50% develop a persistent fistula in ano.

Clinical assessment

A full medical history and proctosigmoidoscopy are necessary to

gain information about sphincter strength and to exclude

associated conditions.

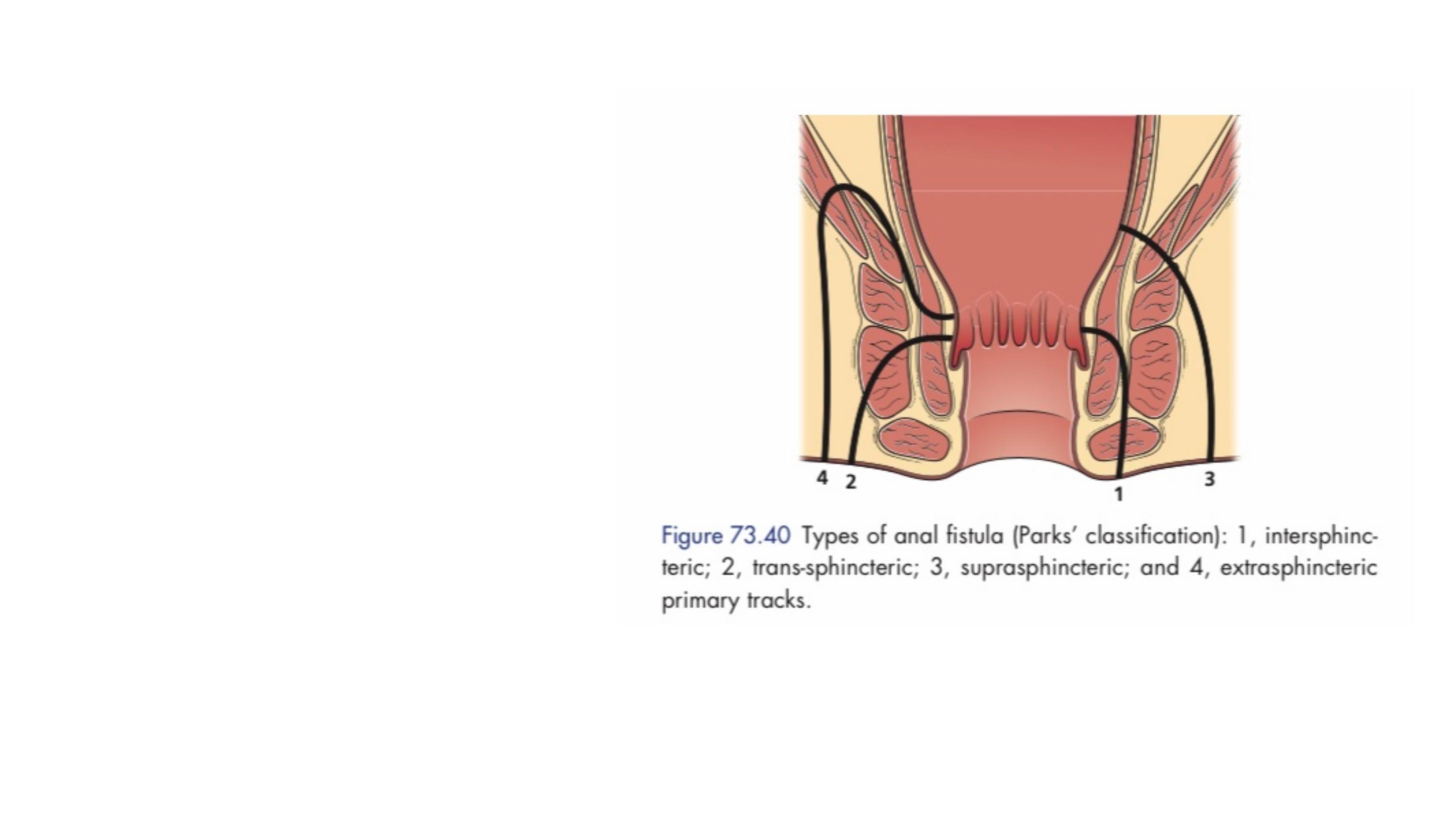

Classification

Parks classification based on

the centrality of intersphincteric

anal gland sepsis (the internal

opening is usually at the

dentate line), which results in a

primary track whose relation to

the external sphincter defines

the type of fistula and which

influences management.

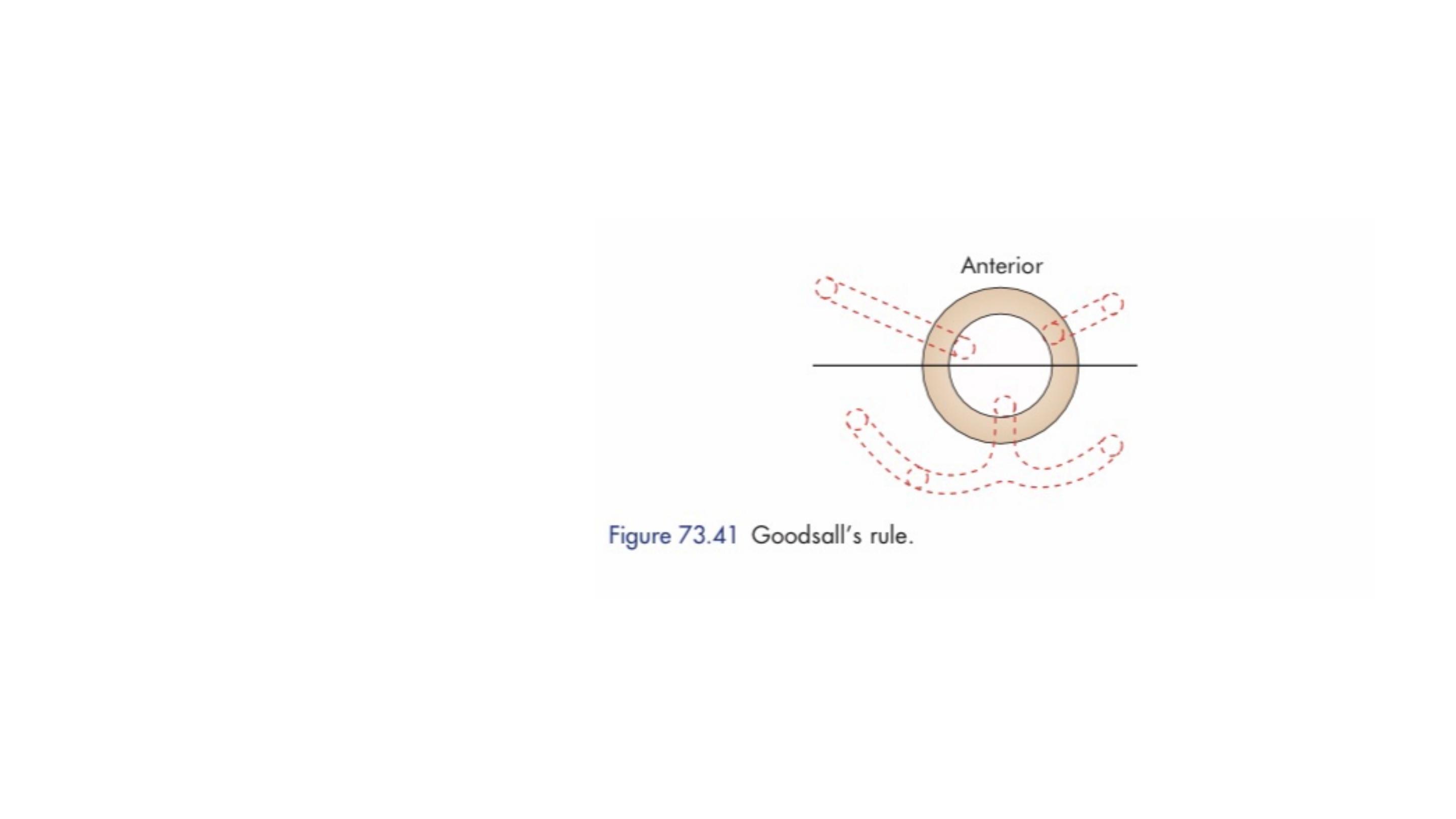

Goodsall’s rule

used to indicate the likely position of

the internal opening according to the position of the

external opening(s), is helpful but not infallible.

In general, fistulas with an external opening anteriorly connect to the internal

opening by a short, radial tract. Fistulas with an external opening posteriorly

track in a curvilinear fashion to the posterior midline.

Special investigations

Clinical examination will give some indication of functional anal sphincter

length, resting tone and voluntary squeeze

Anal manometry objectively gives useful information about sphincter integrity

and can also be used to delineate fistulae.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is acknowledged to be the ‘gold standard’ for

fistula imaging, but it is limited by availability and cost and is usually reserved for

difficult recurrent cases. The great advantage of MRI is its ability to demonstrate

secondary extensions, which may be missed at surgery and which are the cause

of persistence.

Fistulography and computed tomography (CT) both have limitation but are

useful techniques if an extrasphincteric fistula is suspected.

Full examination under anaesthesia should be repeated before surgical

intervention.

Patients with minimal symptoms, especially if they have compromised

sphincters, may be managed expectantly.

Eradication of sepsis requires surgery, the aim of which must be

balanced with the preservation of continence.

Most fistulae are relatively straightforward to deal with; however, a

minority are extremely problematic.

Management

Fistulotomy

, or laying open, is the surest way of getting rid of a fistula, but, by

definition, it involves division of all those structures lying between the external

and internal openings.

Fistulectomy, This technique involves coring out of the fistula.

Loose setons

are tied such that there is no tension upon the

encircled tissue; there is no intent to cut the tissue.

Tight or cutting setons

are placed with the intention of cutting

through the enclosed muscle.

Simple intersphincteric fistulas can often be treated by fistulotomy.

Fistulas that include less than 30% of the sphincter muscles can

often be treated by sphincterotomy without significant risk of

major incontinence

High transsphincteric fistulas and suprasphincteric which

encircle a greater amount of muscle, are more safely treated by

initial placement of a seton

Fibrin glue and a variety of collagen-based plugs also have been used to

treat persistent fistulas with variable results.

Higher fistulas may be treated by an endorectal advancement flap.

A more recent technique, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT),

also shows promise.

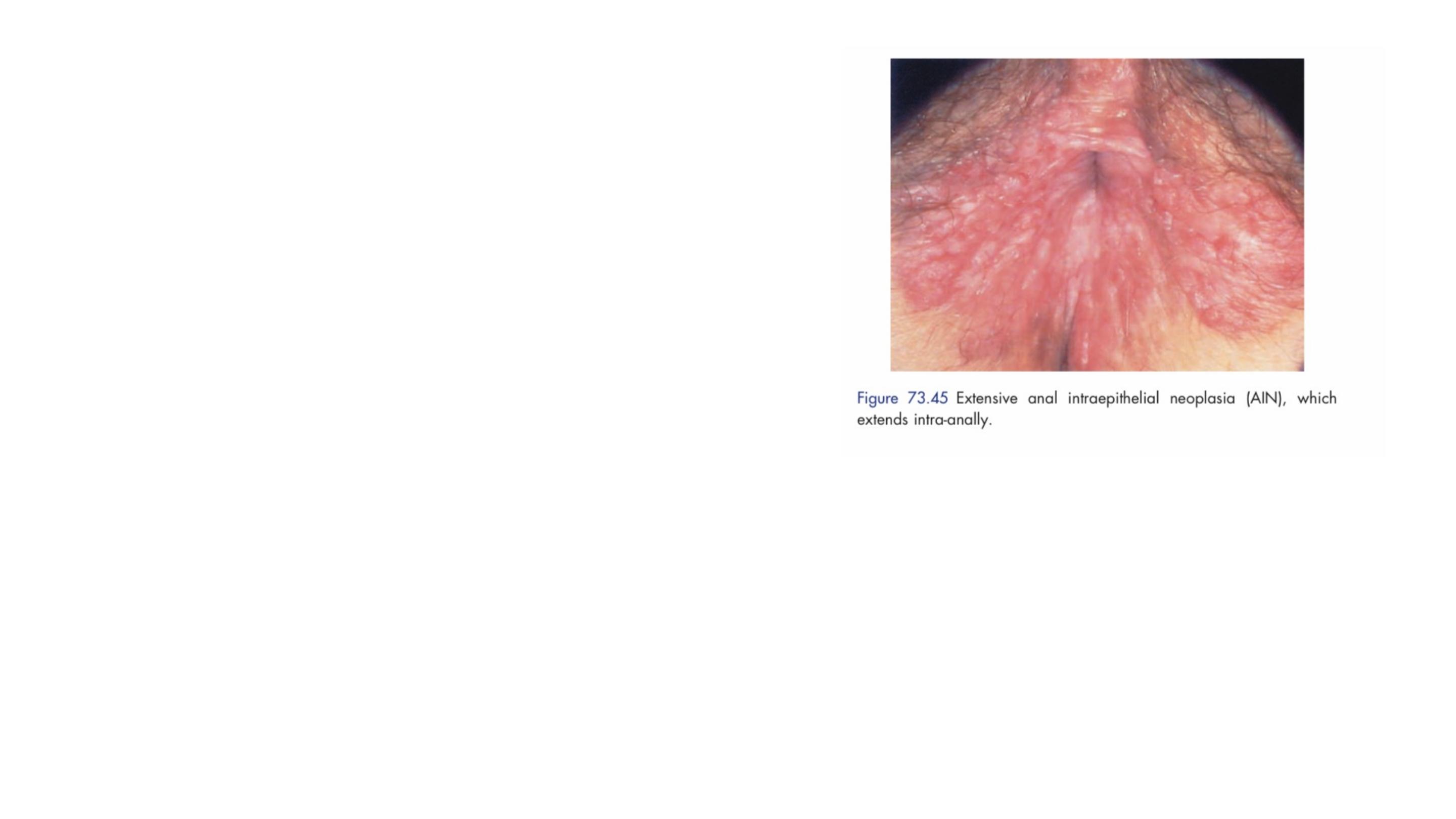

ANAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia is a multifocal

virally induced dysplasia of the perianal or

intra-anal epidermis which is associated with

the human papilloma virus (most frequently

subtypes 6, 11, 16 and 18).

At-risk groups include patients with HIV, as well as immunocompromised

patients.

It is classified according to the degree of dysplasia on biopsy into AIN I, AIN II and

AIN III, according to the lack of keratocyte maturation and extension of the

proliferative zone from the lower third (AIN I) to the full thickness of the epithelium

(AIN III),

Approximately 10 per cent of AIN III lesions will progress to anal

carcinoma at five years.

Focal disease may be excised and local excision is effective for

lesions <30 per cent of the circumference of the anus.

More widespread disease can be dealt with surgically by wide

local excision and closure of the resultant defect by flap or skin

graft, with or without covering colostomy.

Anal cancer

■

Uncommon tumour, which is usually a squamous cell carcinoma

■

Anal SCC is associated with HPV (especially subtypes 16, 18, 31 or 33) in

70–90 per cent of cases

■

More prevalent in patients with HIV infection

■

Pain and bleeding are the most common symptoms and mass, pruritus or

discharge is less common.

■ May affect the anal verge or anal canal

■

On examination, anal margin tumours look like malignant ulcers.

■

Anal canal tumours are palpable as irregular indurated tender ulceration.

Lymphatic spread is to the inguinal lymph nodes.

Despite good results with chemoradiotherapy 20–25 per cent of

patients will have local disease relapse. After thorough

assessment, these patients may require radical abdominoperineal

resection,

Treatment is by chemoradiotherapy in the first instance.

Adenocarcinomata

within the anal canal are usually extensions

of distal rectal cancers.

Rarely, adenocarcinoma may arise from anal glandular epithelium

or develop within a longstanding (usually complex) anal fistula

Treatment is as for low rectal cancers (i.e. abdominoperineal excision of

the rectum (APER) with or without previous radiotherapy or

chemoradiotherapy), but prognosis is less good.

Pilonidal Disease

It consists of a hair-containing sinus or abscess occurring in the

intergluteal cleft.

The cleft creates a suction that draws hair into the midline pits when a

patients sits. These ingrown hairs may then become infected and

present acutely as an abscess in the sacrococcygeal region.

An acute abscess should be incised and drained as soon as the

diagnosis is made.

Chronic pilonidal sinus

The simplest method involves unroofing the tract, curetting the base,

and marsupializing the wound.

Alternatively, a small lateral incision can be created and the pit excised.

Complex and/or recurrent sinus tracts may require more extensive

resection and closure with a Z-plasty, advancement flap, or rotational

flap.