د مهند الشاله

Lecture 1

The Anus and Anal canal

Describe applied anatomy and histology of the anal canal

Describe the clinical features, investigations and principles of

management of common anorectal diseases

Learning objectives

Surgical anatomy

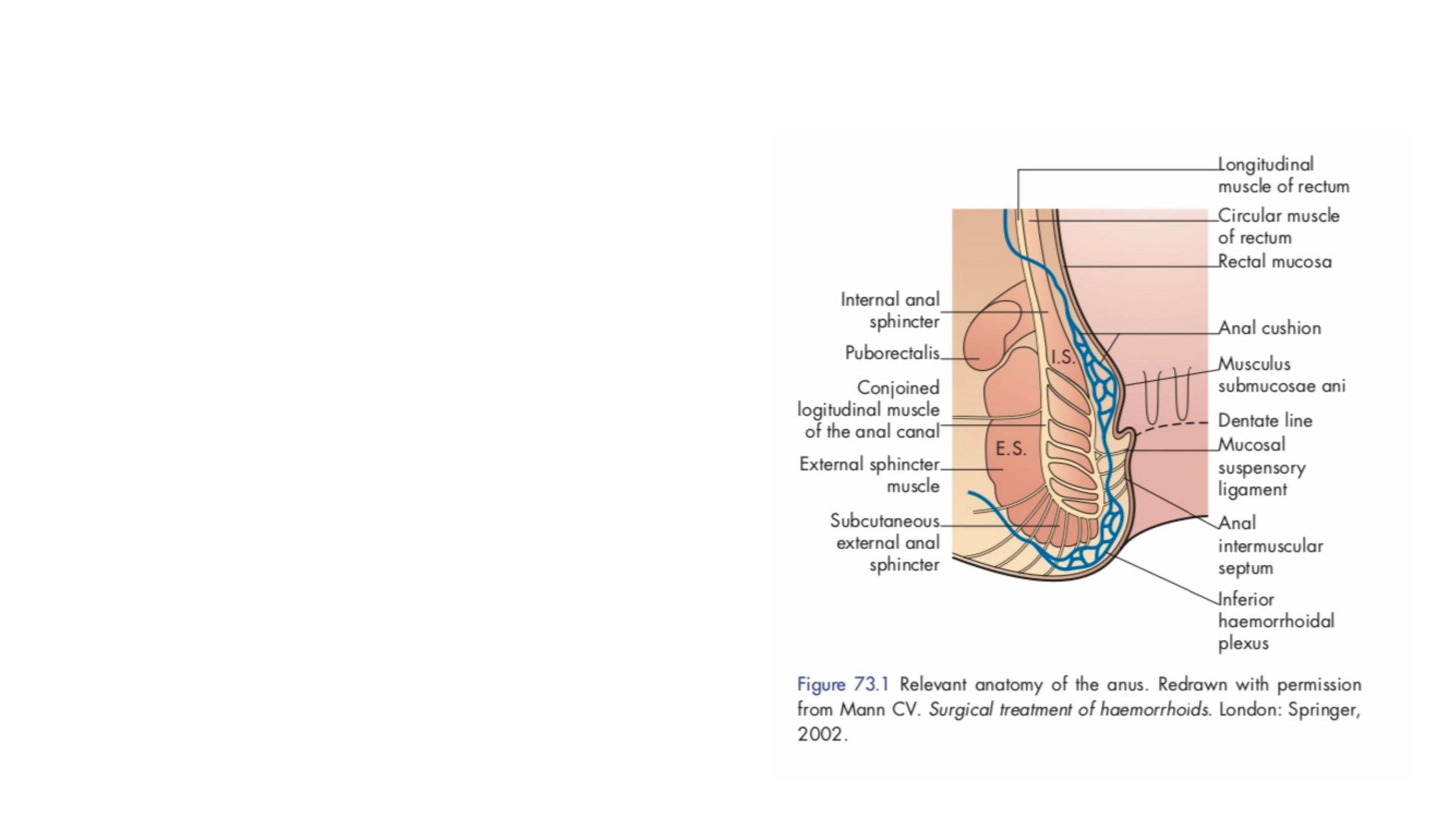

The anal canal commences at the

level where the rectum passes

downwards and backwards for

around 4 cm through the pelvic

diaphragm and ends at the anal

verge.

The internal sphincter is a condensation

of the circular muscle of the bowel wall.

The external sphincter is a composite

striated muscle. Its lower fibres encircle

the anal canal and they can be subdivided

into deep, superficial and subcutaneous

portions.

The dentate line represents the site

of fusion of the proctodaeum and

post- allantoic gut.

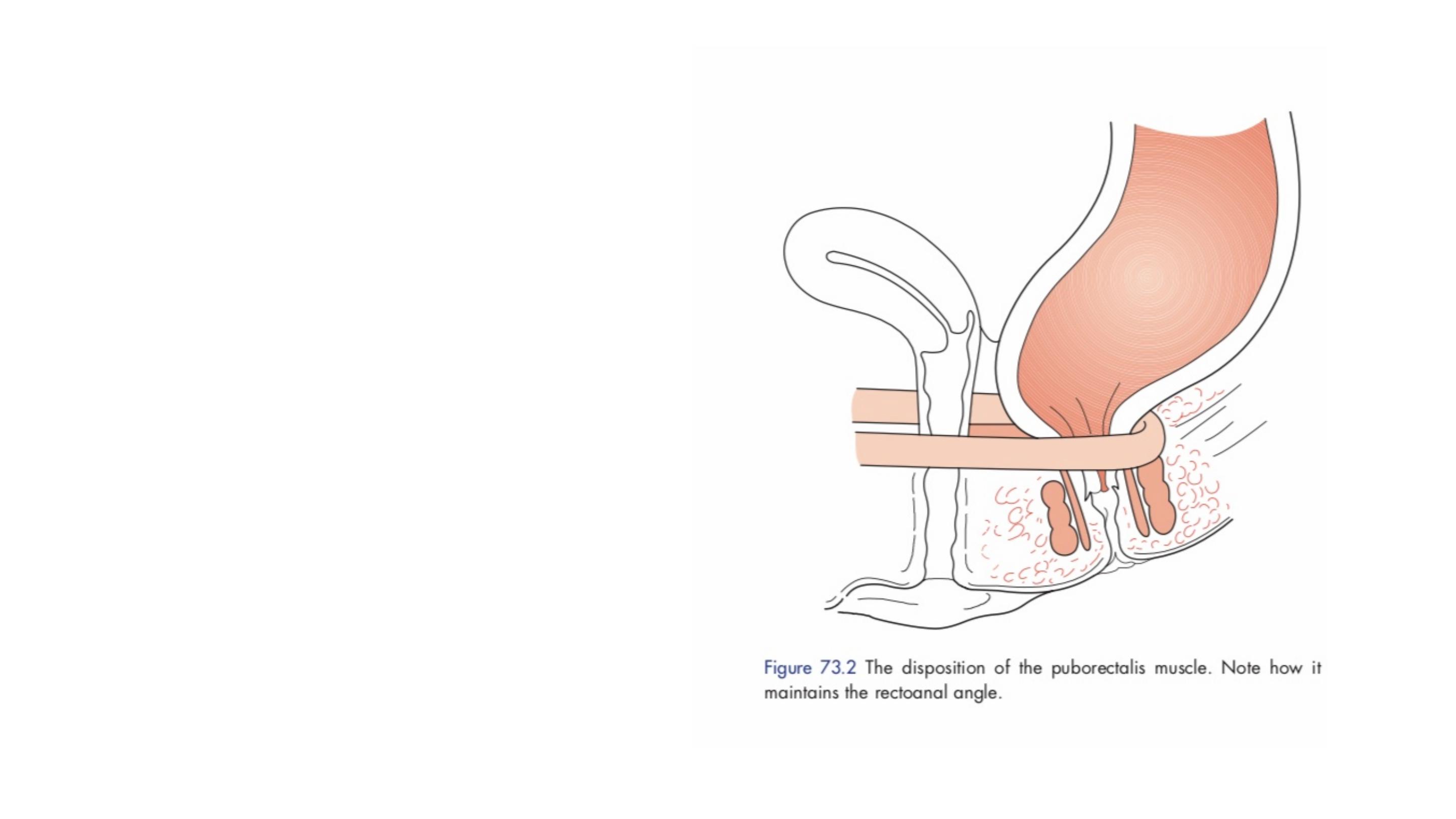

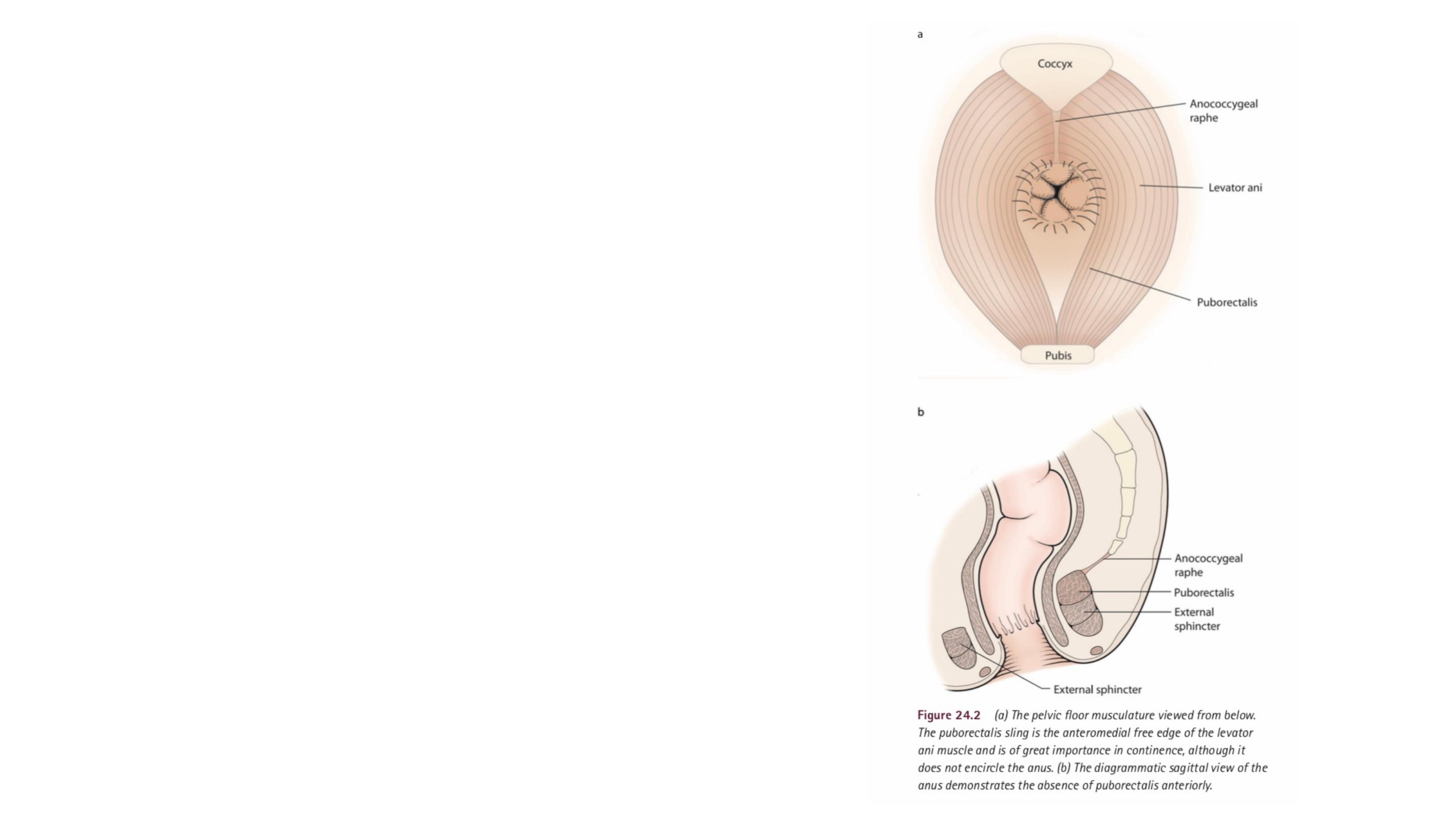

Superiorly, the external sphincter

blends with the puborectalis portion

of the levator ani muscle of the

pelvic floor.

The puborectalis muscle sling does

not encircle the anus and is

deficient anteriorly.

The anal glands lie partly in the submucosal plane and partly between the

sphincters in the intersphincteric plane; infection in these glands is thought to

be the main cause of peri- anal sepsis and fistulae. The orifices of the glands

open just above the anal valves and this is therefore the commonest site of

the internal opening for a fistula.

Vascular plexi lie beneath the mucosa of the anal canal.

The main arterial inflow is from the terminal branches of the superior

rectal artery, which classically divides into a left lateral, a right

anterolateral and a right posterolateral branch; they anastomose with

branches of the inferior rectal artery. Three small swellings, or anal

cushions, are associated with the underlying vascular plexi.

Blood supply to the anal canal is via superior, middle and inferior rectal vessels

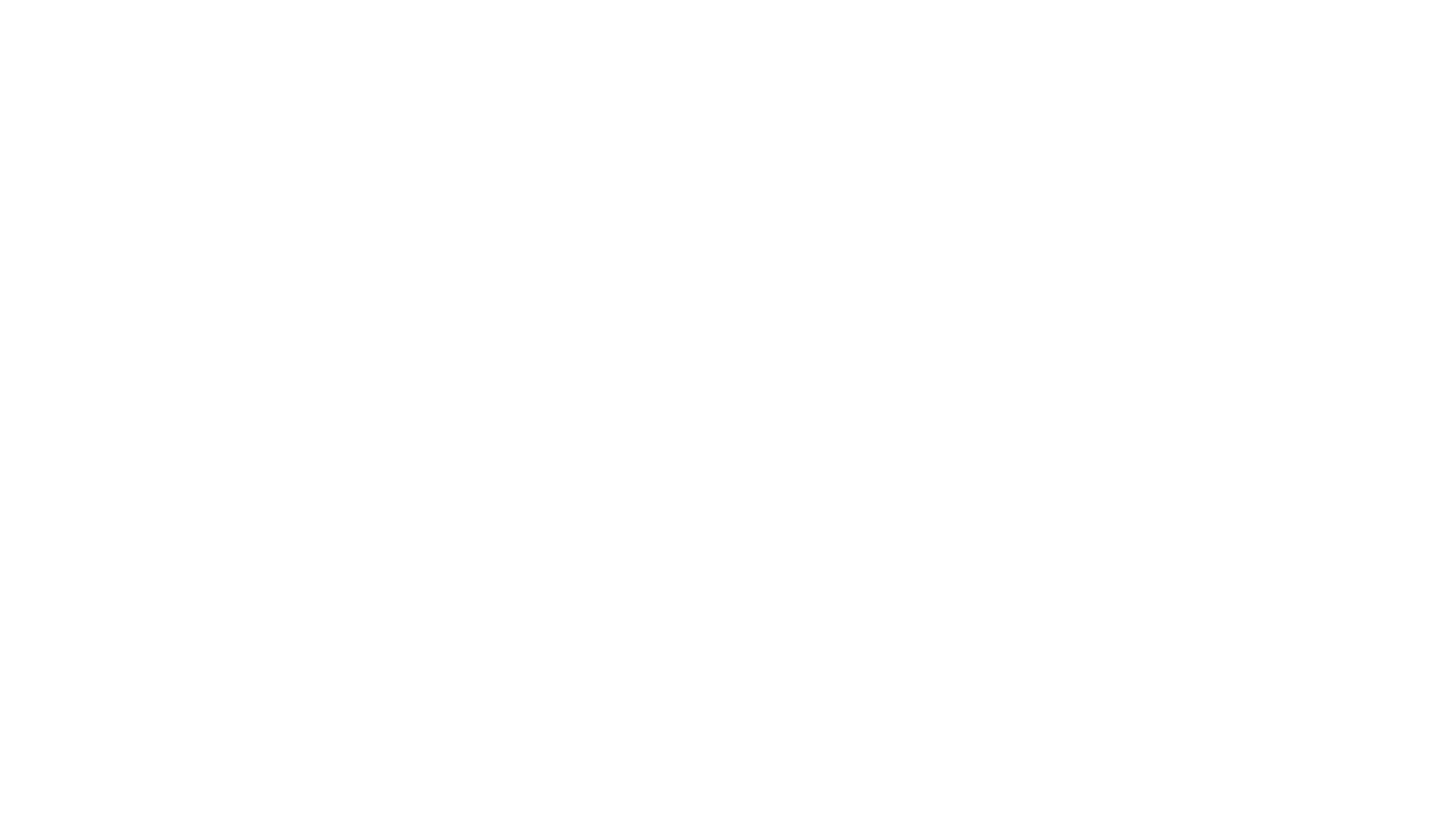

The epithelium of anal canal

The lining of the anal canal above

the dentate line is similar to the

columnar epithelium of the colon

and rectum, except that there is a

junctional zone extending for about

1 cm above the dentate line.

Below this line it is modified skin,

or anoderm, consisting of

squamous epithelium.

This change in the mucosa is important, as malignant lesions

arising in the distal anal canal are more likely to be squamous cell

carcinomas than adenocarcinomas.

The dentate line also marks the watershed for lymphatic drainage.

The upper anal canal drains to the inferior mesenteric nodes and

the lower anal canal to the inguinal nodes.

The dentate line is also the division between somatic and visceral

sensation. Distal pathology in the anal canal may thus be

extremely painful.

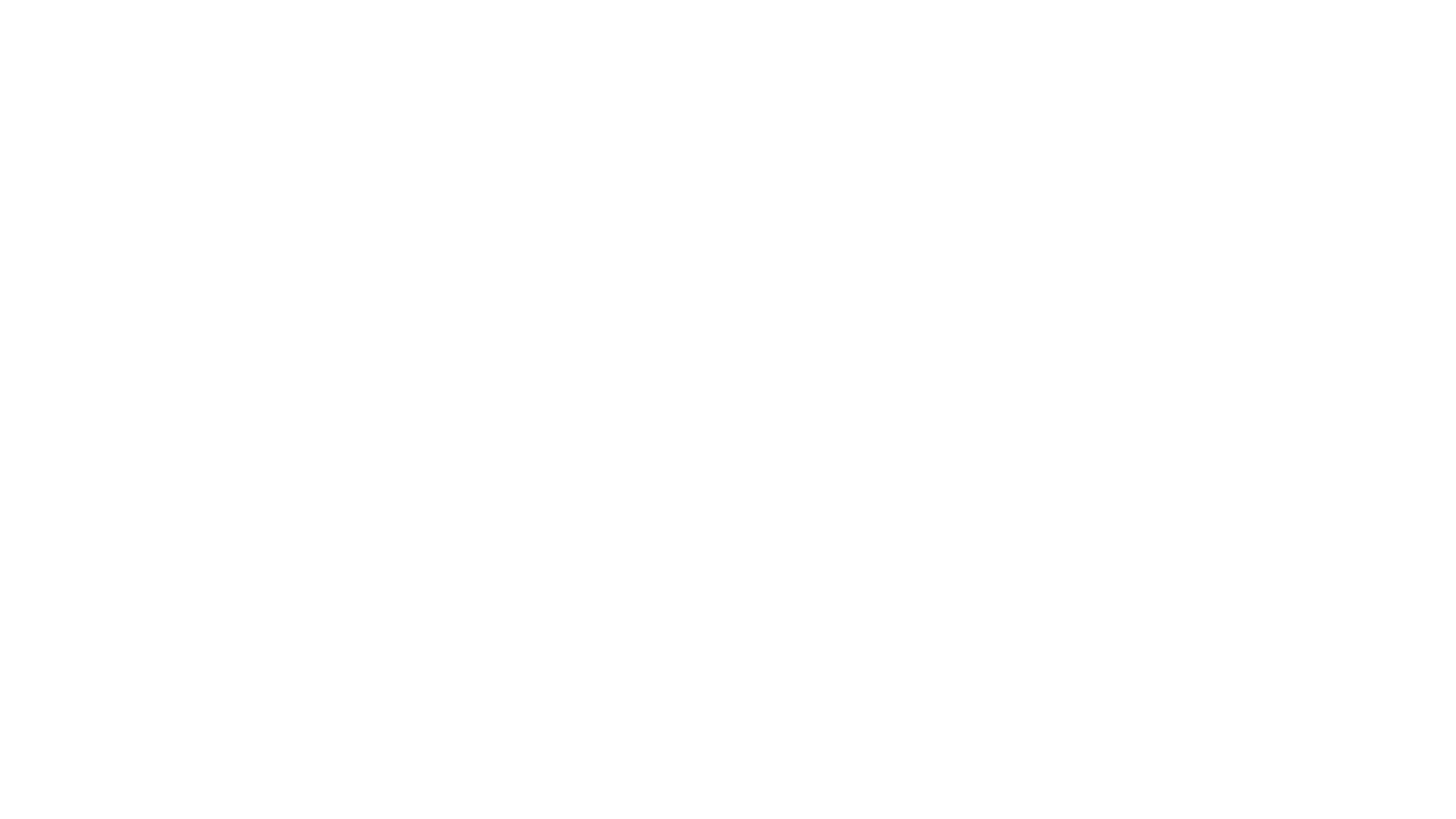

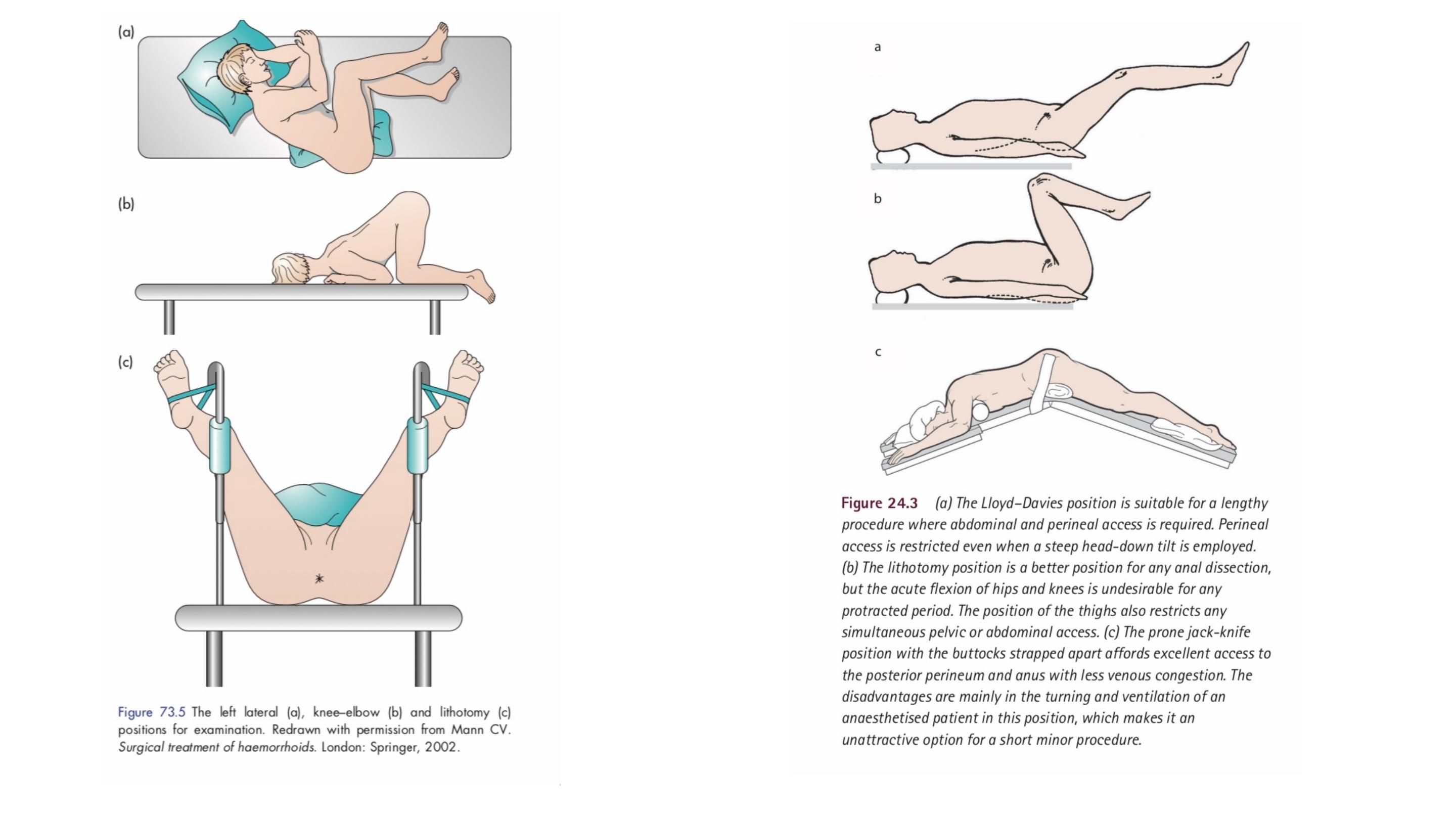

EXAMINATION OF THE ANUS

Careful clinical examination will be diagnostic in the vast majority of

patients complaining of anal symptoms, but it requires a relaxed patient

who is informed of what the examination will entail, a private environment, a

chaperone (for the security of both parties) and good light.

A rectal examination is essential for any patient with anorectal and/or

bowel symptoms – ‘If you don’t put your finger in, you might put your

foot in it’

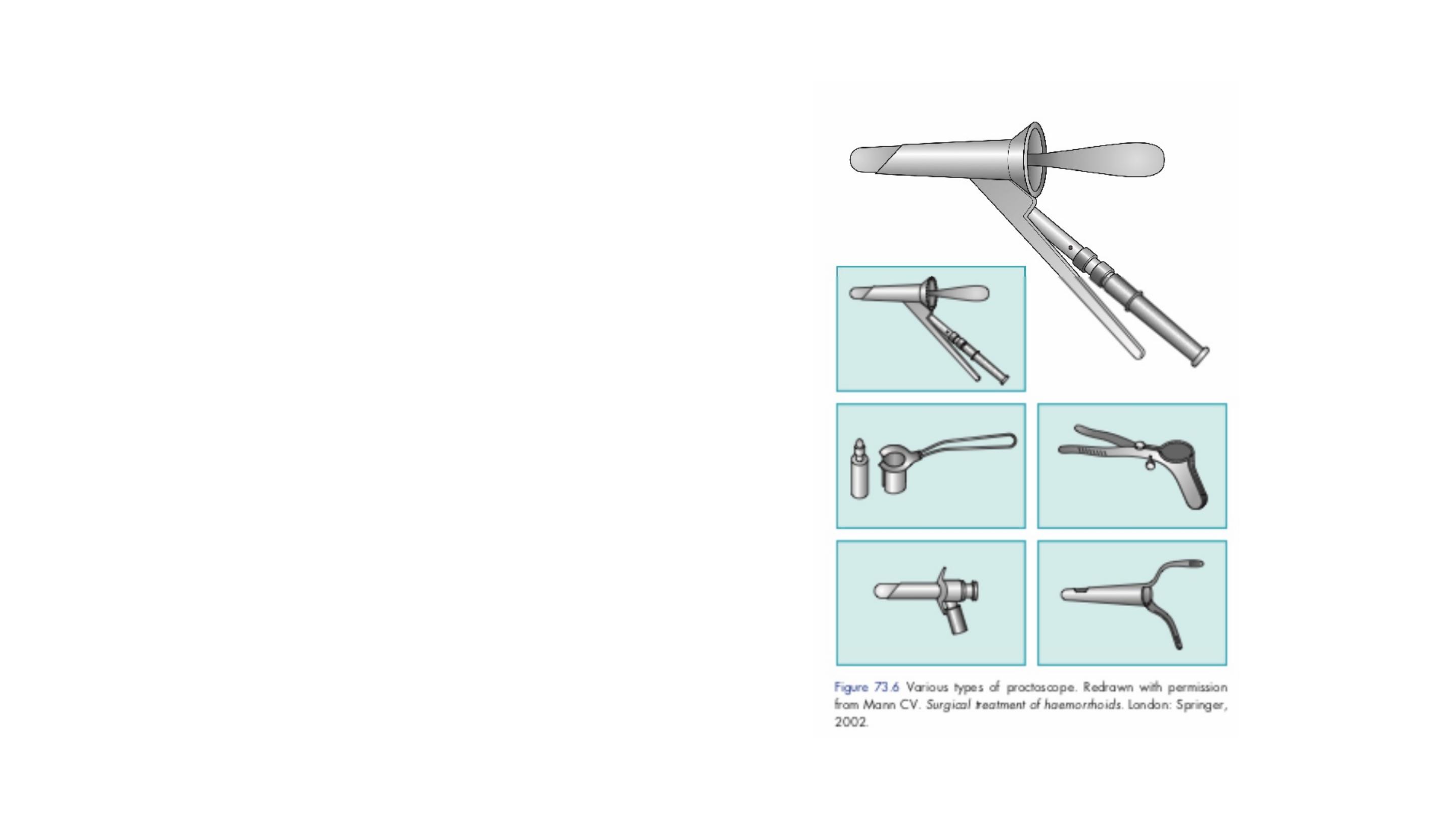

A proctosigmoidoscopy is essential in any

patient with bowel symptoms, and particularly

if there is rectal bleeding

ANAL FISSURE

An anal fissure is a longitudinal split in the anoderm of the distal

anal canal which extends from the anal verge proximally towards,

but not beyond, the dentate line.

Symptoms

:

•

Pain on defaecation

•

Bright-red bleeding

•

Mucous discharge

•

Constipation

Anal fissure typically located in the Posterior midline of anus.

~10% of women have anterior midline lesions—weakest muscular

support

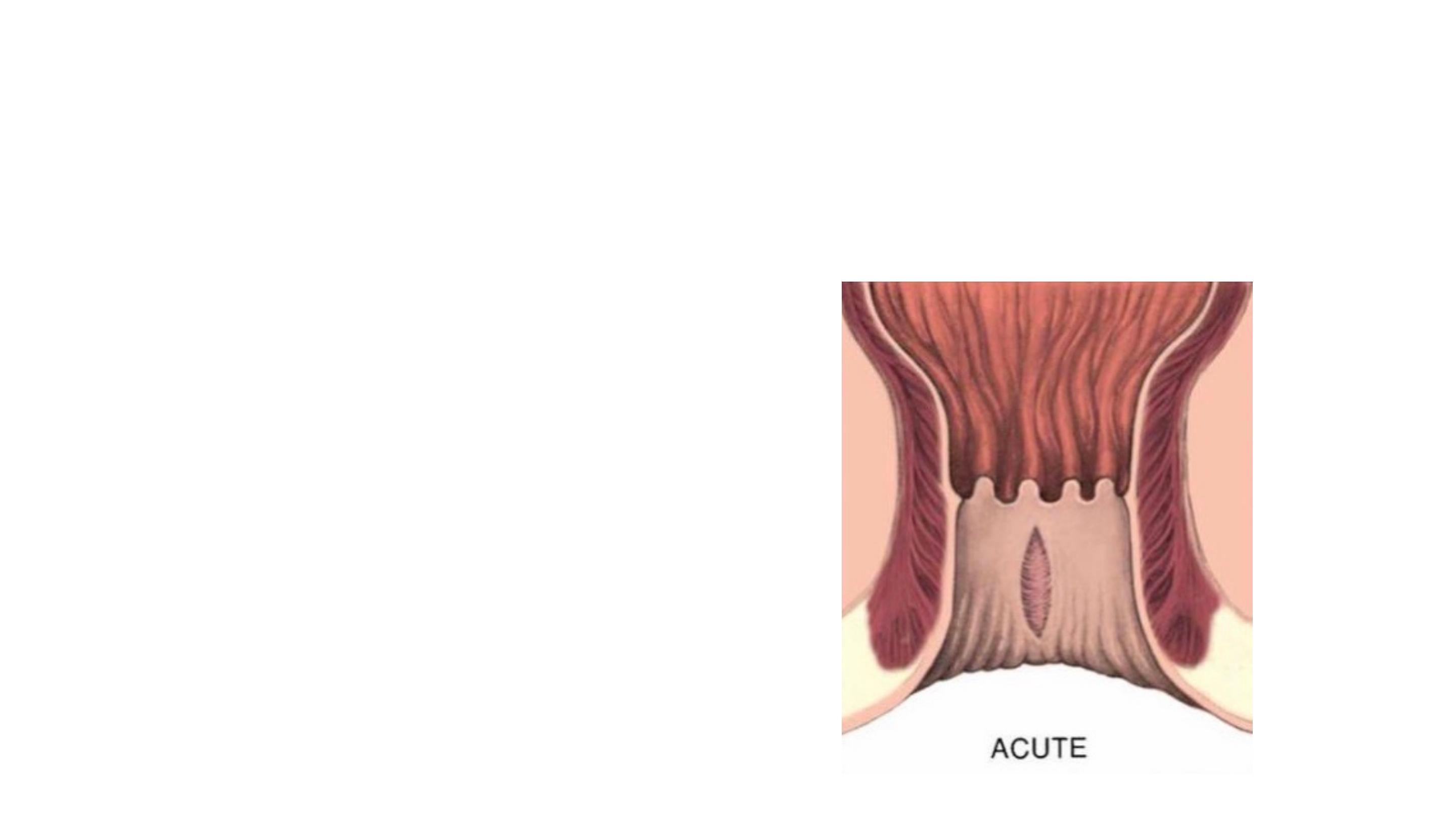

Classically, acute anal fissures arise from the trauma caused by the

strained evacuation of a hard stool or, less commonly, from the

repeated passage of diarrhoea.

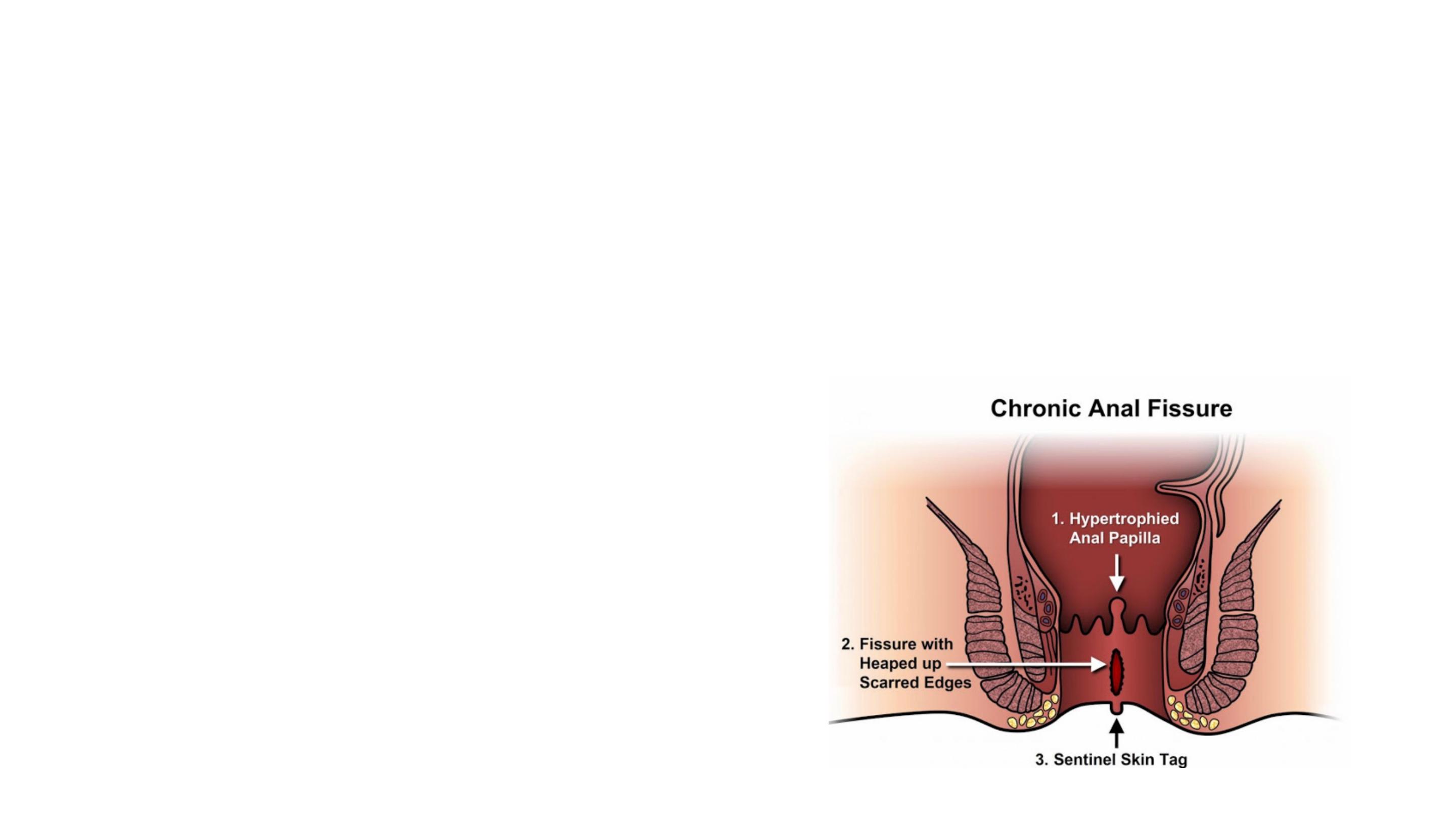

Chronicity may result from repeated

trauma, anal hypertonicity and vascular

insufficiency, either secondary to

increased sphincter tone or because

the posterior commissure is less well

perfused than the remainder of the anal

circumference.

Treatment of an anal fissure

■

Conservative initially, consisting of stool-bulking agents and

softeners, and chemical agents in the form of ointments designed

to relax the anal sphincter and improve blood flow

■

Conservative management should result in the healing of almost

all acute and the majority of chronic fissures.

Such agents include glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 0.2 per cent applied four times per

day to the anal margin (although this may cause headaches) and diltiazem 2 per

cent applied twice daily.

■ Surgery if above fails, consisting of lateral internal sphincterotomy or

anal advancement flap

Hemorrhoids are cushions of submucosal tissue containing venules,

arterioles, and smooth muscle fibers that are located in the anal canal.

Three hemorrhoidal cushions are found in the left lateral, right anterior,

and right posterior positions.

Cushions are thought to function as part of the continence mechanism

and aid in complete closure of the anal canal at rest. Because

hemorrhoids are a normal part of anorectal anatomy, treatment is only

indicated if they become symptomatic.

Haemorrhoids (Greek: haima, blood; rhoos, flowing; synonym:

piles, Latin: pila, a ball)

External haemorrhoids relate to venous channels of the inferior

haemorrhoidal plexus and located distal to the dentate line and are

covered with anoderm.

Because the anoderm is richly innervated, thrombosis of an external

hemorrhoid may cause significant pain.

Internal hemorrhoids are located proximal to the dentate line and

covered by insensate anorectal mucosa.

Combined internal and external hemorrhoids straddle the dentate

line and have characteristics of both internal and external

hemorrhoids.

Causes of hemorrhoid

Engorged anal cushions and vessels from increased pelvic/

abdominal pressures:

•

Constipation/straining

•

Pregnancy

•

Ascites/abdominal tumors

•

Portal hypertension

Symptoms of haemorrhoids:

•

Bright-red, painless bleeding

•

Mucous discharge

•

Prolapse

•

Pain only on prolapse

Internal hemorrhoids may prolapse or bleed, but rarely become painful

unless they develop thrombosis and necrosis (usually related to severe

prolapse, incarceration, and/or strangulation).

■ First degree – bleed only, no prolapse

■ Second degree – prolapse, but reduce spontaneously

■ Third degree – prolapse and have to be manually reduced

■ Fourth degree – permanently prolapsed

Internal hemorrhoid are graded according to the extent of

prolapse into four degree:

Complications of haemorrhoids

■ Strangulation and thrombosis

■ Ulceration

■ Gangrene

■ Portal pyaemia

■ Fibrosis

Management

Exclusion of other causes of rectal bleeding, especially colorectal

malignancy, is the first priority.

Important measures include attempts at normalising bowel and defaecatory

habits: only evacuating when the natural desire to do so arises, adopting a

defaecatory position to minimise straining, and the addition of stool soften-

ers and bulking agents to ease the defaecatory act.

Various creams can be inserted into the rectum from a collapsible tube fitted

with a nozzle, at night and before defaecation. Suppositories are also useful.

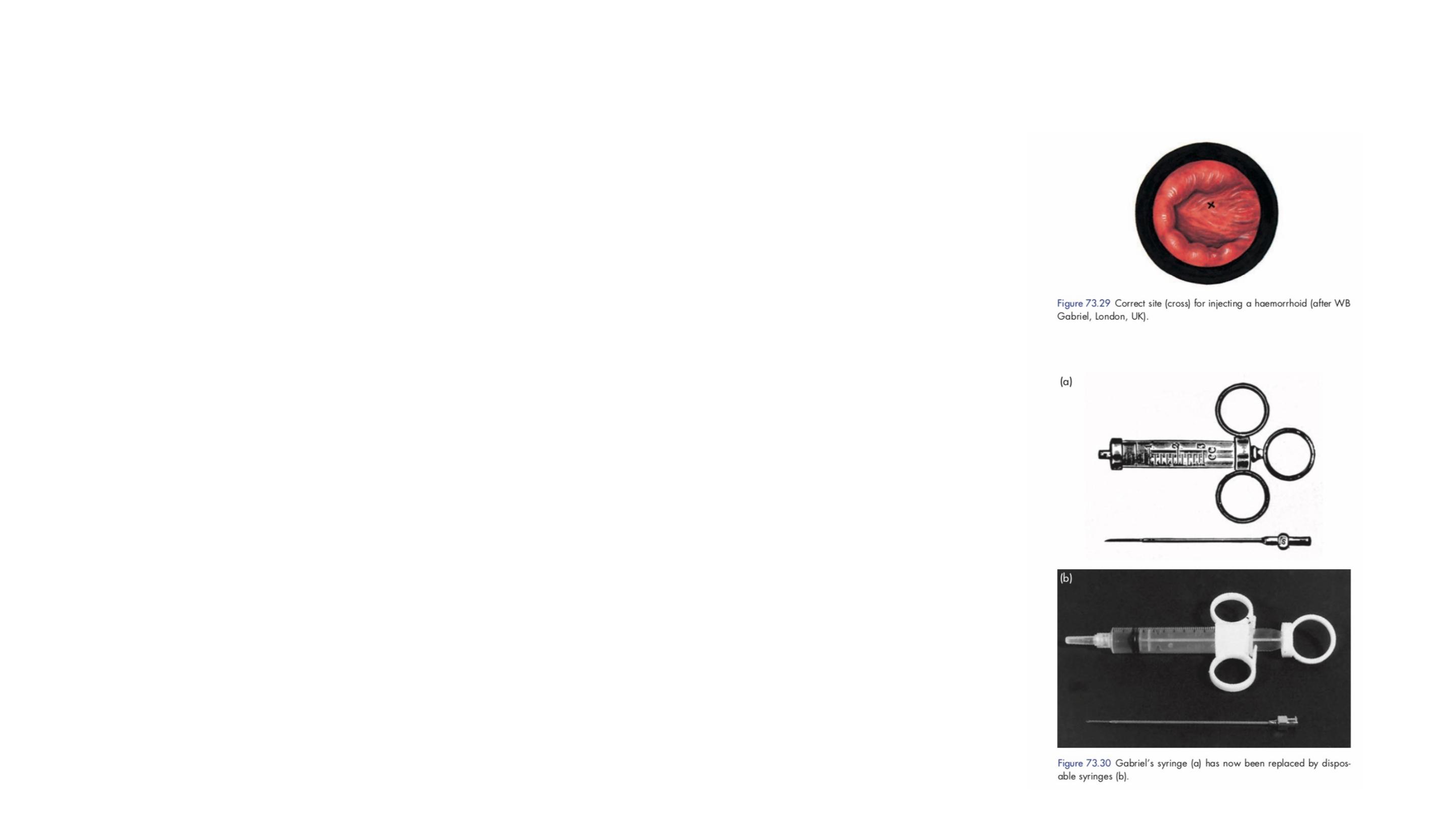

Sclerotherapy

A submucosal injection of 5 per cent phenol

in almond oil causes both thrombosis of the

feeding vessels and fibrosis, which tethers

the lax mucosa, thus reducing prolapse.

Infrared photocoagulation

With infrared photocoagulation (IRPC) an infrared radiation

source is applied immediately proximal to the upper

margin of the haemorrhoid.

The aim is to create fibrosis, cause obliteration of

the vascular channels and hitch up the anorectal

mucosa.

In those with first- or second-degree piles whose symptoms are not

improved by conservative measures,

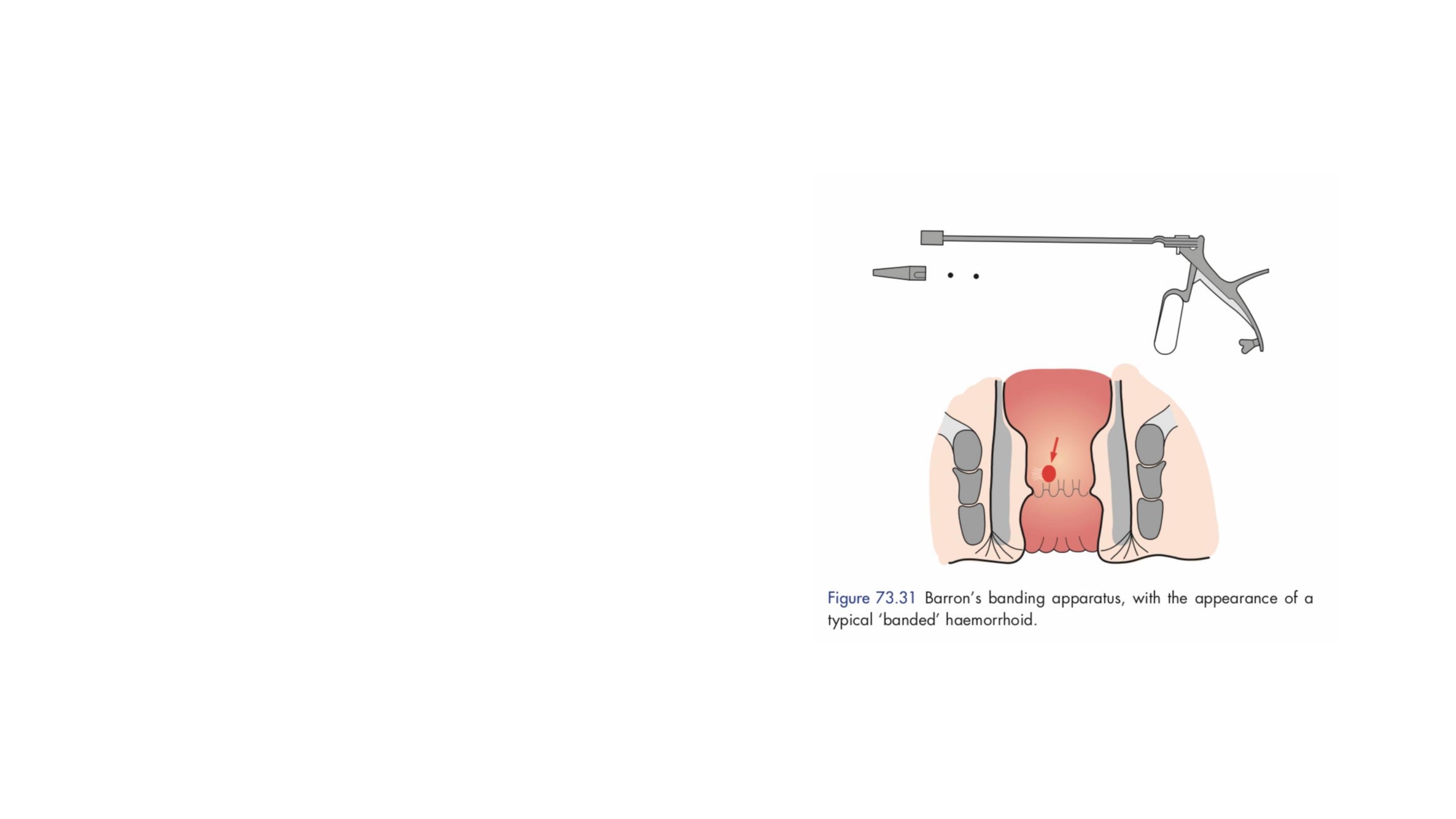

Banding

For more bulky piles, banding has been

shown to be efficacious, but it is

associated with more discomfort.

The Barron’s bander is a commonly

available device used to slip tight elastic

bands onto the base of the pedicle of each

haemorrhoid.

The bands cause ischaemic necrosis of the

piles, which slough off within 10 days; this

may be associated with bleeding, about

which the patient must be warned.

Operation management

The indications for haemorrhoidectomy include:

Third- and fourth-degree haemorrhoids

Second-degree haemorrhoids that have not been cured by

non-operative treatments

Fibrosed haemorrhoids

Interoexternal haemorrhoids when the external

haemorrhoid is well defined.

Surgical treatment of haemorrhoids

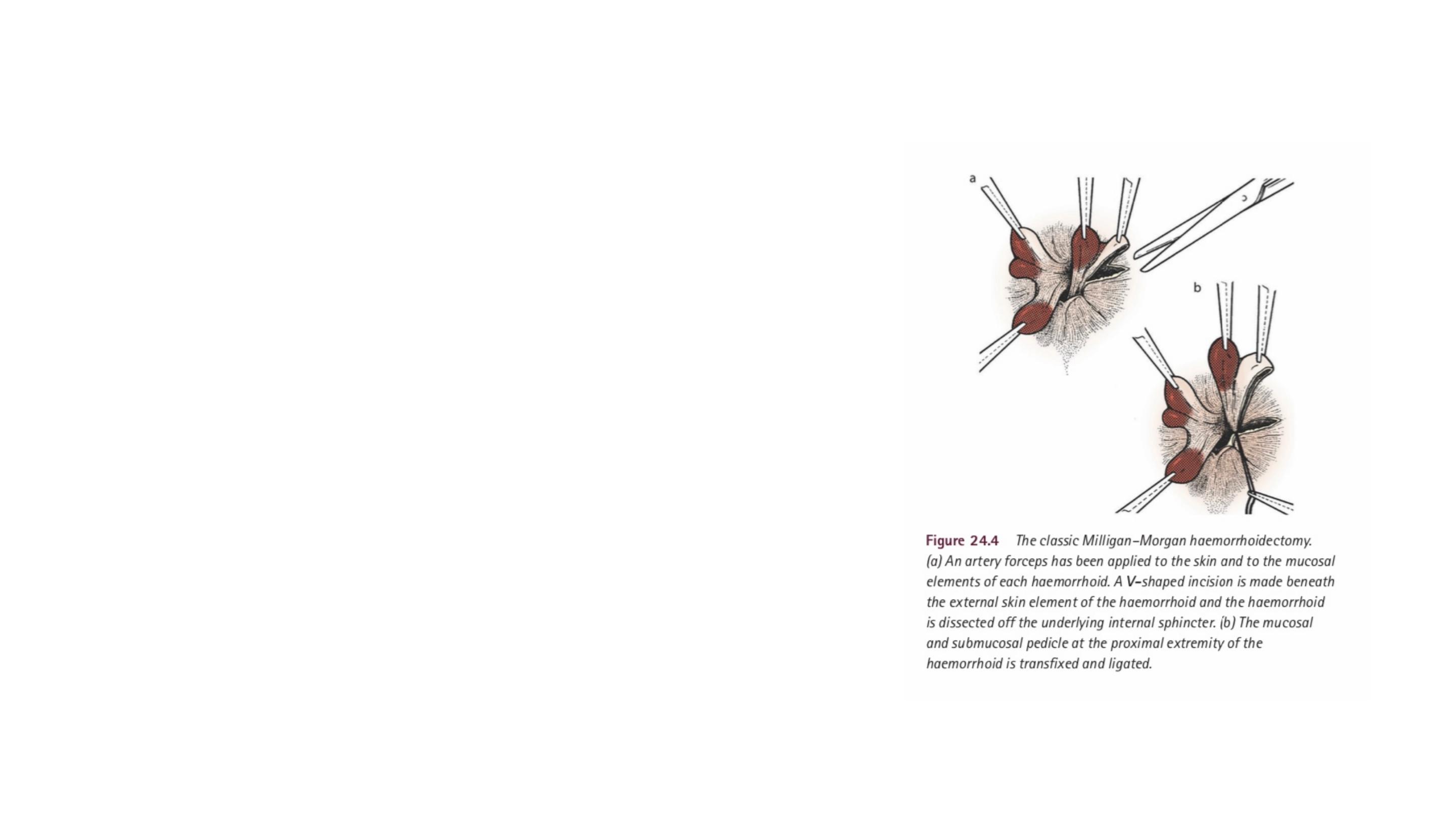

MILLIGAN–MORGAN HAEMORRHOIDECTOMY

In this classical operation involves resection of

hemorrhoidal tissue.

Adequate bridges of skin and mucosa must be left

intact between the excisions to prevent anal

stenosis developing during healing.

Closed Submucosal Hemorrhoidectomy.

The Parks or Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy involves resection of

hemorrhoidal tissue and closure of the wounds with absorbable

suture.

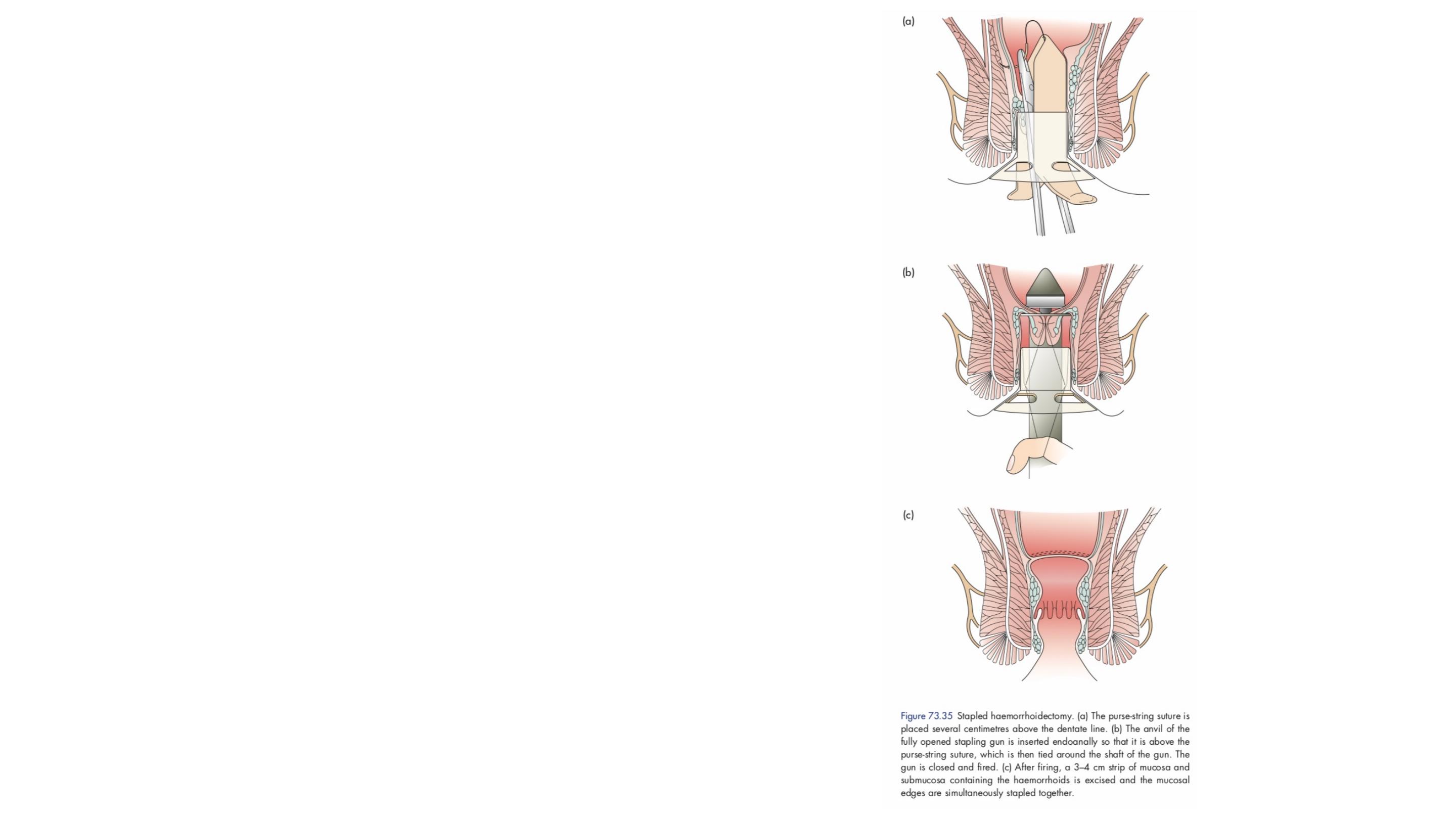

Procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids

(PPH) removes a short circumferential segment

of rectal mucosa proximal to the dentate line

using a circular stapler.

This effectively ligates the venules feeding the

hemorrhoidal plexus and fixes redundant mucosa

higher in the anal canal.

Transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation

In this procedure, a Doppler probe is used to identify the artery or arteries

feeding the hemorrhoidal plexus. These vessels are then ligated.

Complications of haemorrhoidectomy

Early

•

Pain

•

Acute retention of urine

•

Reactionary haemorrhage

Late

•

Secondary haemorrhage

•

Anal stricture

•

Anal fissure

•

Incontinence

Thank you