كلية الطب

جامعة بابل

Lec3

Hepatology

Chronic HBV and HCV

Dr.Hassan aljumaily

•

Chronic hepatitis B virus infection:

Hepatitis B is one of the most common causes of chronic liver

disease and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. Hepatitis B may

cause an acute viral hepatitis however, acute infection is often

asymptomatic, particularly when acquired at birth. Many

individuals with chronic hepatitis B are also asymptomatic .

The risk of progression to chronic liver disease depends on the

source and timing of infection .

Full recovery occurs in 90–95% of adults following acute

HBV infection. The remaining 5–10% develop a chronic

hepatitis B infection that usually continues for life, although

later recovery occasionally occurs.

Infection passing from mother to child at birth leads to

chronic infection in the child in 90% of cases and recovery is

rare. Chronic infection is also common in immunodeficient

individuals, such as those with Down’s syndrome or human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Combined HBV and

HDV infection causes more aggressive disease

Source of hepatitis B infection and risk of chronic

infection

Horizontal transmission (10%)

• Injection drug use

• Infected unscreened blood products

• Tattoos/acupuncture needles

• Sexual (homosexual and heterosexual)

• Close living quarters/playground play as a toddler

(may

contribute to high rate of horizontal transmission

in Africa)

Vertical transmission (90%)

• HBsAg-positive mother

Clinical presentation:

■Incubation period of acute infection is 1 to 4 months

■Symptomatic acute hepatitis (e.g., abdominal pain, low-grade

fever, nausea, jaundice) occurs in 30% of adults, but in only 10%

of children younger than 4 years of age

■Clinical symptoms usually normalize after 1 to 3 months

■Many are chronic inactive carriers with normal liver

chemistries, presence of anti-HBe, and minimal serum HBV DNA.

Inactive carriers remain at risk for HCC. This phase of the

disease is also known as immune tolerance.

■Reactivation of HBV replication (presence of anti-HBe, high

serum HBV DNA, intermittently elevated ALT) can occur in the

setting of immunosuppression (i.e., chemotherapy)

■Extrahepatic manifestations (in 10% to 20% of chronic HBV)

include polyarteritis nodosa, membranous or

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and mixed cryoglobu

INVESTIGATION

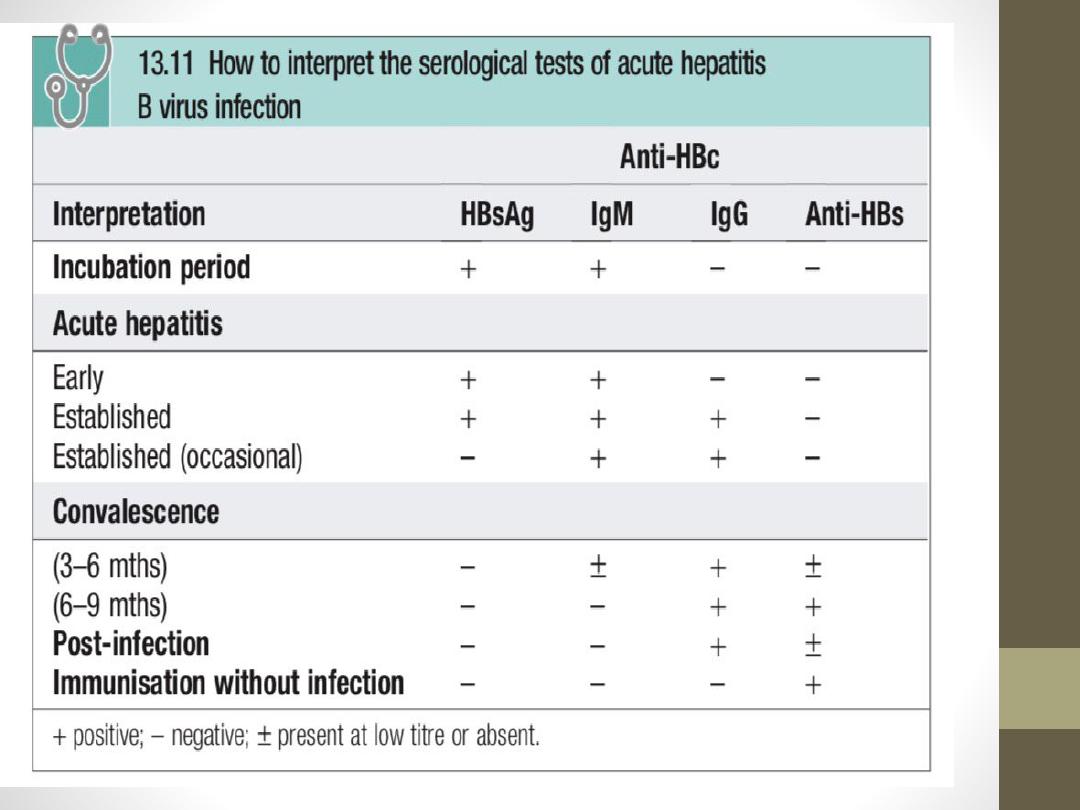

Serology: In acute infection HBsAg is a reliable marker of HBV

infection . Antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) appears after about

3–6 mths and persists for many years or even permanently.

Anti-HBs implies either a previous infection, in which case anti-

HBc (see below) is usually also present; or previous

vaccination, when anti-HBc is not present.

The hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) is not found in the blood

but antibody to it (anti-HBc) appears early in the illness. Anti-

HBc is initially of IgM type, with IgG antibody appearing later.

The hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is an indicator of active viral

replication. It appears only transiently at the outset of the

illness and is followed by the production of antibody (anti-

HBe). Chronic HBV infection (see below) is marked by the

persistence of HBsAg and anti-HBc (IgG) in the blood. Usually,

HBeAg or anti-HBe is also present. Interpretation of serological

tests is shown in Box

Viral load:

HBV-DNA can be measured by PCR in the blood. Viral loads are

usually >105 copies/mL in the presence of active viral replication,

as indicated by the presence of e antigen. In contrast, in those

with low viral replication, HBsAg- and anti-HBe-positive, viral

loads are usually <105 copies/mL. High viral loads are also found

in e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis, which occurs in the Far

East and is due to a mutation.

Management

Acute hepatitis B:

Treatment is supportive, with monitoring for

acute liver failure, which occurs in < 1% of

cases.

Chronic hepatitis B:

1- This develops in 5–10% of acute cases and

is lifelong. No drug is consistently able to

render patients HBsAg-negative.

2- Lamivudine and tenofovir are both effective, but viral

mutations causing resistance commonly develop. Tenofovir

also has anti-HIV efficacy, so monotherapy should be avoided

in HIV co-infected patients to prevent HIV antiviral drug

resistance. Interferon alfa is most effective in patients with low

viral load and high transami- nases, in whom it acts by

augmenting a native immune response.

3-Interferon is contraindicated in the presence of cirrhosis, as it

may precipitate liver failure. Longer-acting pegylated

interferons, which can be given once weekly, have been

evaluated in both HBeAg- positive and HBeAg-negative chronic

hepatitis.

The use of post-liver transplant prophylaxis with lamivudine

and hepatitis B immunoglobulins has reduced the re-infection

rate to 10% and increased 5-yr survival to 80%, making

transplantation an acceptable treatment option.

•

PREVENTION

1.

Individuals are most infectious when markers of continuing viral

replication, such as HBeAg, and high levels of HBV-DNA are present in

the blood. The virus is about ten times more infectious than hepatitis C,

which in turn is about ten times more infectious than HIV.

2.

A recombinant hepatitis B vaccine containing HBsAg is available

(Engerix) and is capable of producing active immunisation in 95% of

normal individuals. The vaccine should be offered to those at special risk

of infection who are not already immune, as evidenced by anti-HBs in the

blood .

The vaccine is

in

effective in those already infected by HBV.

3.

Infection can also be prevented or minimised by the intramuscular

injection of hyperimmune serum globulin prepared from blood containing

anti-HBs.

This should be given within 24 hours, or

•

at most a week of exposure to infected blood in circumstances likely to

cause infection (e.g. needle stick injury, contamination of cuts or mucous

membranes).

Vaccine can be given together with hyperimmune

globulin(active–passive immunization) .

Neonates born to hepatitis B-infected mothers should be immunised at birth

and given immunoglobulin. Hepatitis B serology should then be checked at

12 months of age

At-risk groups meriting hepatitis B vaccination

•

Parenteral drug users

•

Men who have sex with men

•

Close contacts of infected individuals

•

Newborn of infected mothers

•

Regular sexual partners

•

Patients on chronic haemodialysis

•

Patients with chronic liver disease

•

Medical, nursing and laboratory personnel

Hepatitis C

•

This is caused by an RNA flavivirus.

Acute symptomatic

infection with hepatitis C is rare

. Most individuals are

unaware of when they became infected and are only

identified when they develop chronic liver disease.

80% of

individuals exposed to the virus become chronically infected

and late spontaneous viral clearance is rare

.(unlike HBV).

•

Hepatitis C infection is usually identified in asymptomatic

individuals screened because they have risk factors for

infection or have incidentally been found to have abnormal

liver blood tests. Although most individuals remain

asymptomatic until progression to cirrhosis occurs, fatigue

can complicate chronic infection and is unrelated to the

degree of liver damage.

Risk factors

:

•

Intravenous drug misuse (95% ).

•

Unscreened blood products

•

Vertical transmission (3% risk).

•

Needlestick injury (3% risk).

•

Iatrogenic parenteral transmission (i.e. contaminated

vaccination needles).

•

Sharing toothbrushes

PRESENATION

•

Symptoms often first develop as clinical findings of extra

hepatic manifestations of HCV and most commonly

involve the joints, muscle, and skin. The most commonly

occurring extra hepatic manifestations :

•

Arthralgias ,Paresthesia , Myalgia , sensory neuropathy.

•

Sicca syndrome necrotizing vasculitis,

Cryoglobulinemia.

•

Lymphoma , Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

•

porphyria cutanea tarda ,Pruritus, Lichen planus.

•

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

•

.

Risk factors for manifestations of extra hepatic chronic

hepatitis C infection include advanced age, female sex,

and liver fibrosis

Investigations

1-

Serology and virology

•

The HCV protein contains several antigens that give rise to

antibodies in an infected person and these are used in diagnosis.

It may take 6–12 weeks for antibodies to appear in the blood

following acute infection. In these cases, hepatitis C RNA can be

identified in the blood as early as 2–4 weeks after infection.

•

Active infection is confirmed by the presence of serum

hepatitis C RNA in anyone who is antibody-positive. Anti-HCV

antibodies persist in serum even after viral clearance, whether

spontaneous or post-treatment.

2-

Molecular analysis

•

There are

6

common viral genotypes, the distribution of which

varies worldwide. Genotype has

no

effect on progression of

liver disease , but does affect response to treatment. Genotype 1

less easy to eradicate than genotypes 2 and 3 with traditional

pegylated interferon alfa/ ribavirin-based treatments.

3- Liver function tests

•

LFTs may be normal or show fluctuating serum

transaminases between 50 and 200 U/L. Jaundice is rare and

only usually appears in end-stage cirrhosis.

4-

Liver histology

•

Serum transaminase levels in hepatitis C are a poor

predictor of the degree of liver fibrosis and so a liver biopsy

is often required to stage the degree of liver damage

. The

degree of inflammation and fibrosis can be scored

histologically. The most common scoring system used in

hepatitis C is the Metavir system, which scores fibrosis

from 1 to 4, the latter equating to cirrhosis.

Management

Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C should be determined on a

case-by-case basis. However, treatment is widely recommended for

patients with elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels

who meet the following criteria :

•

Age greater than 18 years.

•

Positive HCV antibody and serum HCV RNA test results.

•

Compensated liver disease (eg, no hepatic encephalopathy or

ascites).

•

Acceptable hematologic and biochemical indices (hemoglobin at

least 13 g/dL for men and 12 g/dL for women; neutrophil count

>1500/mm 3, serum creatinine < 1.5 mg/dL).

•

Willingness to be treated and to adhere to treatment requirements.

•

No contraindications for treatment.

Extra hepatic manifestations

•

N.B A further criterion is liver biopsy findings consistent

with a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis. However, a

pretreatment liver biopsy is not mandatory. It may be

helpful in certain situations, such as in patients with normal

transaminase levels, particularly those with a history of

alcohol dependence, in whom little correlation may exist

between liver enzyme levels and histologic findings.

•

Progression from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis occurs over

20–40 years. Risk factors for progression include:

1-male gender.

2-immunosuppression (such as co-infection with HIV).

3- prothrombotic states and heavy alcohol misuse.

The aim of treatment is to eradicate infection. Until

recently, the treatment of choice was dual therapy with

pegylated interferon- alfa given weekly SC, together

with oral ribavirin, a synthetic nucle- otide analogue.

The length of treatment and efficacy depend on viral

genotype. The main side-effect of ribavirin is

haemolytic anaemia. Side-effects of interferon are

significant and include flu-like symp- toms, irritability

and depression. Recently, triple therapy with the

addition of protease inhibitors (e.g. telaprevir) has

increased the rate of sustained virological response

(defined as loss of virus from serum 6 mths after

completing therapy). Liver transplantation should be

considered when complications of cirrhosis occur.

Unfor- tunately, hepatitis C almost always recurs in

the transplanted liver.