The skin in systemic disease

The skin and internal

malignancy

acne seen with some adrenal tumours

flushing in the carcinoid syndrome

jaundice with a bile duct carcinoma

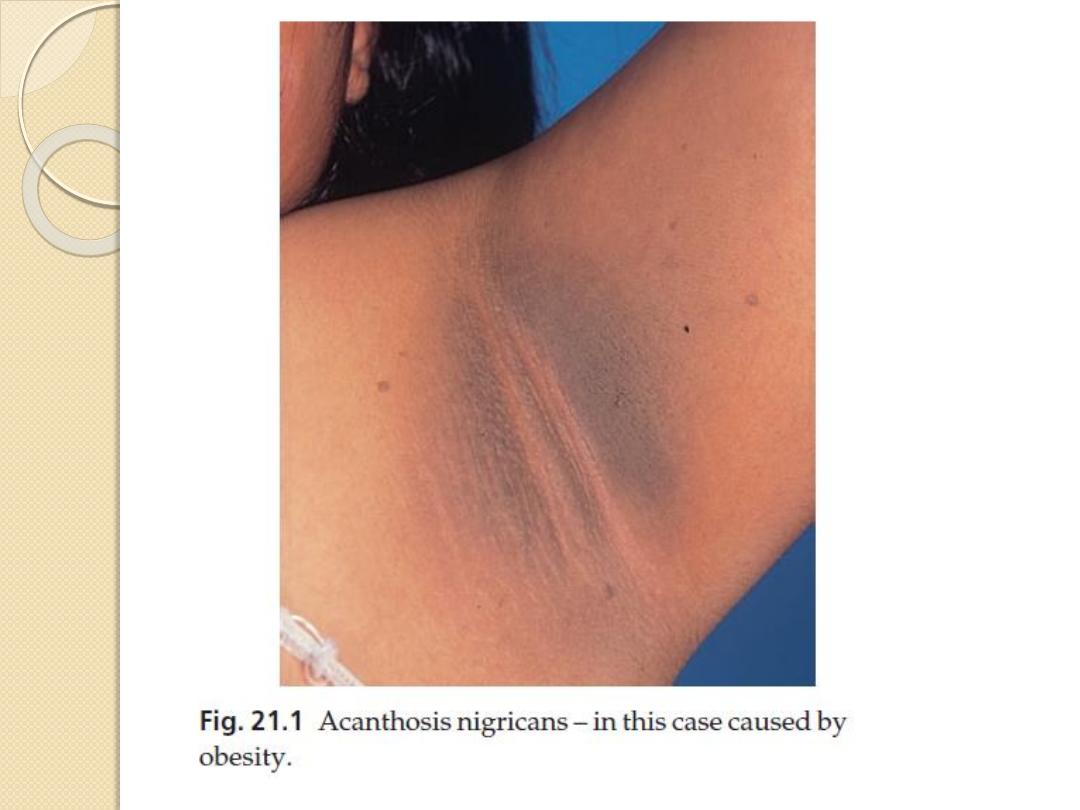

Acanthosis nigricans

is a velvety thickening and pigmentation of the major flexures

caused by:

obesity

metabolic syndrome (including type 2 diabetes with insulin

resistance)

Drugs as nicotinic acid used to treat hyperlipidaemia

the chances are high that a malignant tumour is present,

usually within the abdominal cavity.

Erythema gyratum repens

looks like the grain on wood

The skin and internal

malignancy

Acquired hypertrichosis lanuginosa (‘malignant down’)

is an excessive and widespread growth of fine lanugo hair.

Necrolytic migratory erythema

is a figurate erythema with a moving crusted edge it signals

the presence of a glucagonsecreting tumour of the pancreas.

Bazex syndrome

is a papulosquamous eruption of the fingers and toes, ears

and nose, seen with some tumours of the upper respiratory

tract.

Dermatomyositis, other than in childhood

About 30% of adult patients have an underlying malignancy.

Pay special attention to the ovaries where ovarian cancer

may lurk undetected.

The skin and internal

malignancy

Generalized pruritus

usually a lymphoma

Superficial thrombophlebitis.

the migratory type associated with carcinomas of the

pancreas.

Acquired ichthyosis

especially lymphomas

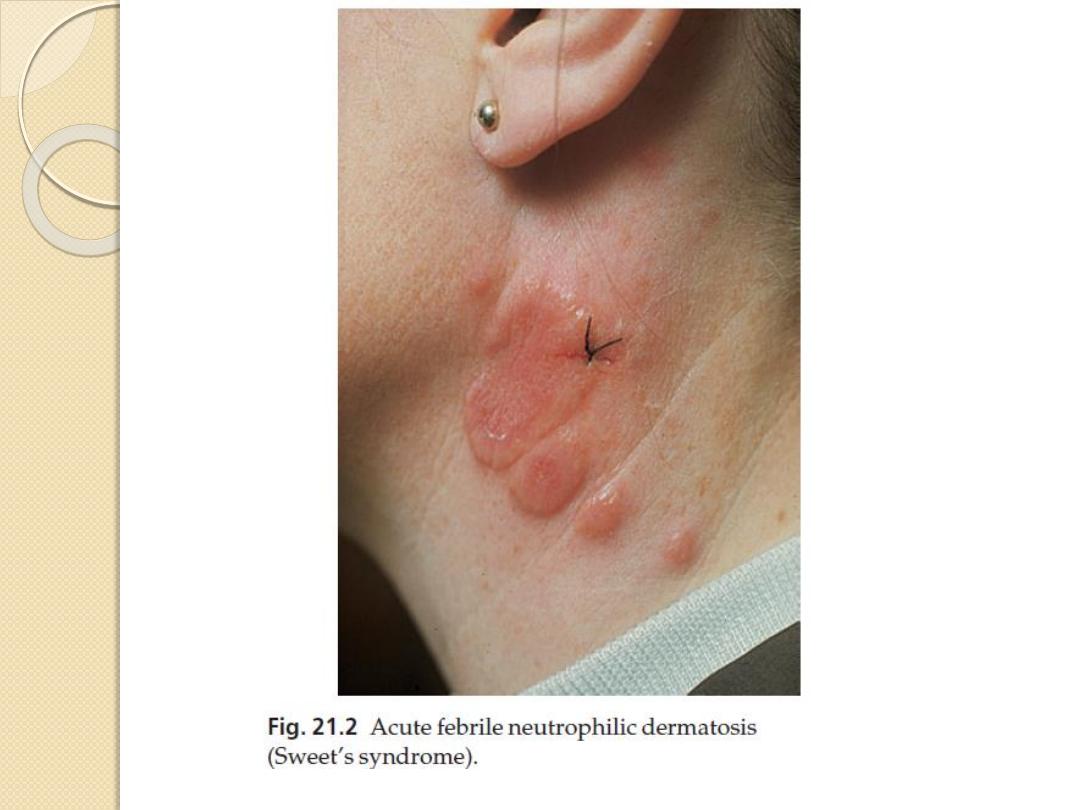

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome)

The classic triad found in association with the red

oedematous plaques consists of fever, a raised erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) and a raised blood neutrophil

count. The most important internal association is with

myeloproliferative disorders.

The skin and internal

malignancy

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

similar to pemphigus vulgaris but with

extensive and persistent mucosal

ulceration.

It is associated with myeloproliferative

malignancies as well as underlying

carcinomas.

Others. Pachydermoperiostosis

The skin and diabetes mellitus

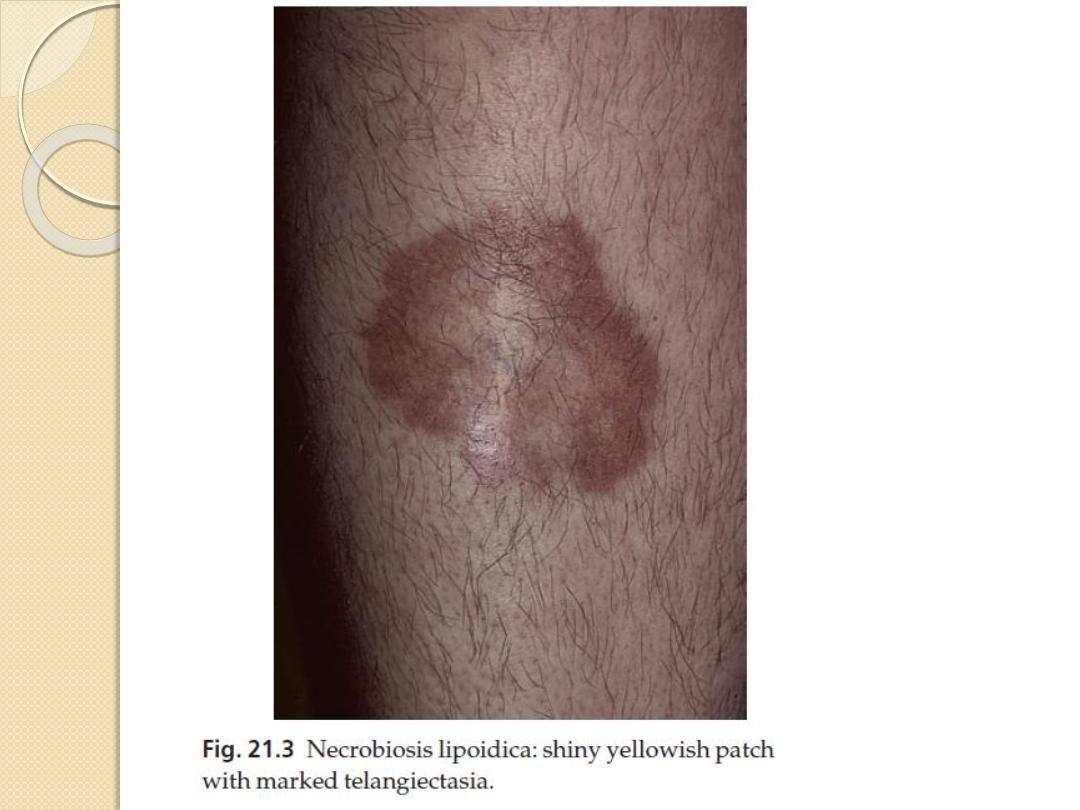

Necrobiosis lipoidica.

Less than 3% of diabetics have necrobiosis, but 11–62%

of patients with necrobiosis will have diabetes.

Non-diabetic necrobiosis patients should be screened

for diabetes as some will have impaired glucose

tolerance or diabetes, and some will become diabetic

later.

The association is with both type 1 and type 2

diabetes.

The lesions appear as one or more discoloured areas

on the fronts of the shins

Early plaques are violaceous but atrophy as the

inflammation goes on and are then shiny, atrophic and

brown–red or slightly yellow.

The skin and diabetes mellitus

The underlying blood vessels are easily seen through the

atrophic skin and the margin may be erythematous or violet.

Minor knocks or biopsy can lead to slow-healing ulcers

Treatment

No treatment is reliably helpful, the atrophy is permanent

the best one can expect from medical treatments is halting

of disease progression.

A strong topical corticosteroid applied to the edge of an

enlarging lesion may halt its expansion.

There is little evidence that good control of the diabetes will

help the necrobiosis.

The skin and diabetes mellitus

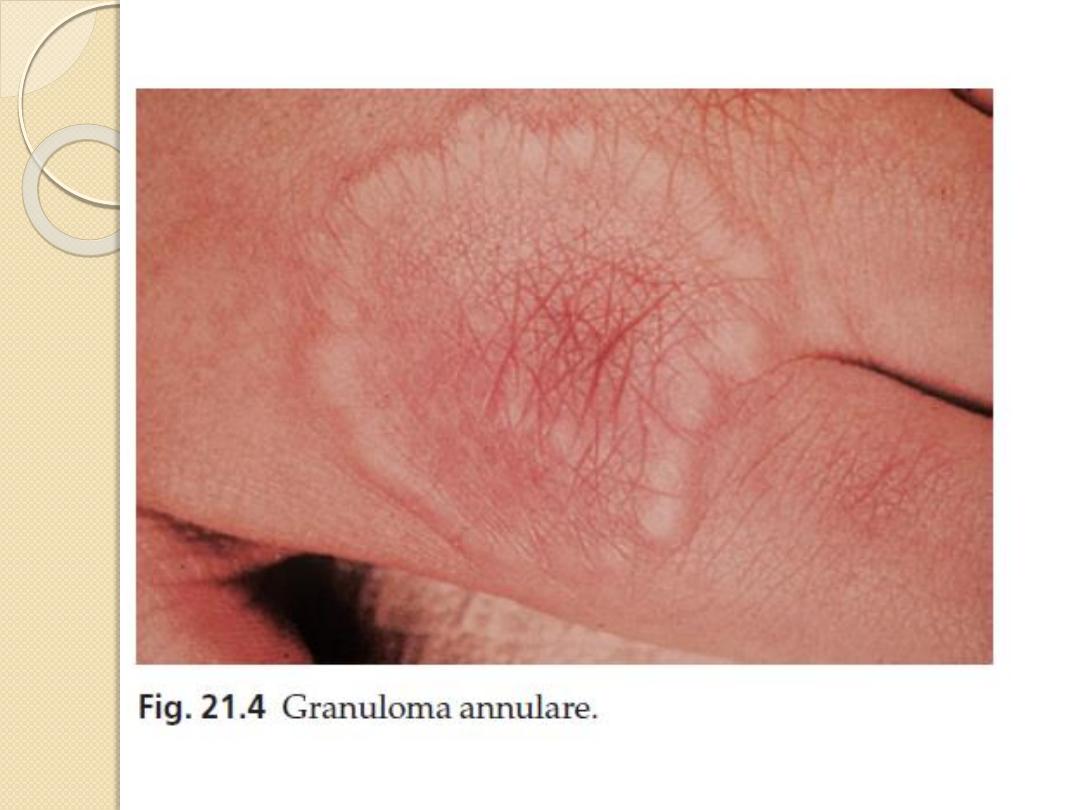

Granuloma annulare.

Clinically, the lesions of the common type of granuloma

annulare often lie over the knuckles and are composed of

dermal nodules fused into a rough ring shape

On the hands the lesions are skin-coloured or slightly pink;

elsewhere a purple colour may be seen.

histology shows a diagnostic palisading granuloma

Lesions tend to go away over the course of a year or two.

Stubborn ones respond to intralesional triamcinolone

injections.

Diabetic dermopathy

In about 50% of type 1 diabetics, multiple small (0.5–1 cm in

diameter) slightly sunken brownish scars can be found on the

limbs, most obviously over the shins.

The skin and diabetes mellitus

Candidal infections

Staphylococcal infections

Vitiligo

Eruptive xanthomas

Stiff thick skin (diabetic sclerodactyly or

cheiroarthropathy)

on the fingers and hands, demonstrated by the

‘prayer sign’ in which the fingers and palms

cannot be opposed properly

Atherosclerosis with ischaemia or gangrene of feet.

Neuropathic foot ulcers.

The skin in liver disease

Pruritus

This is related to obstructive jaundice and

may precede it

Pigmentation

With bile pigments and sometimes melanin

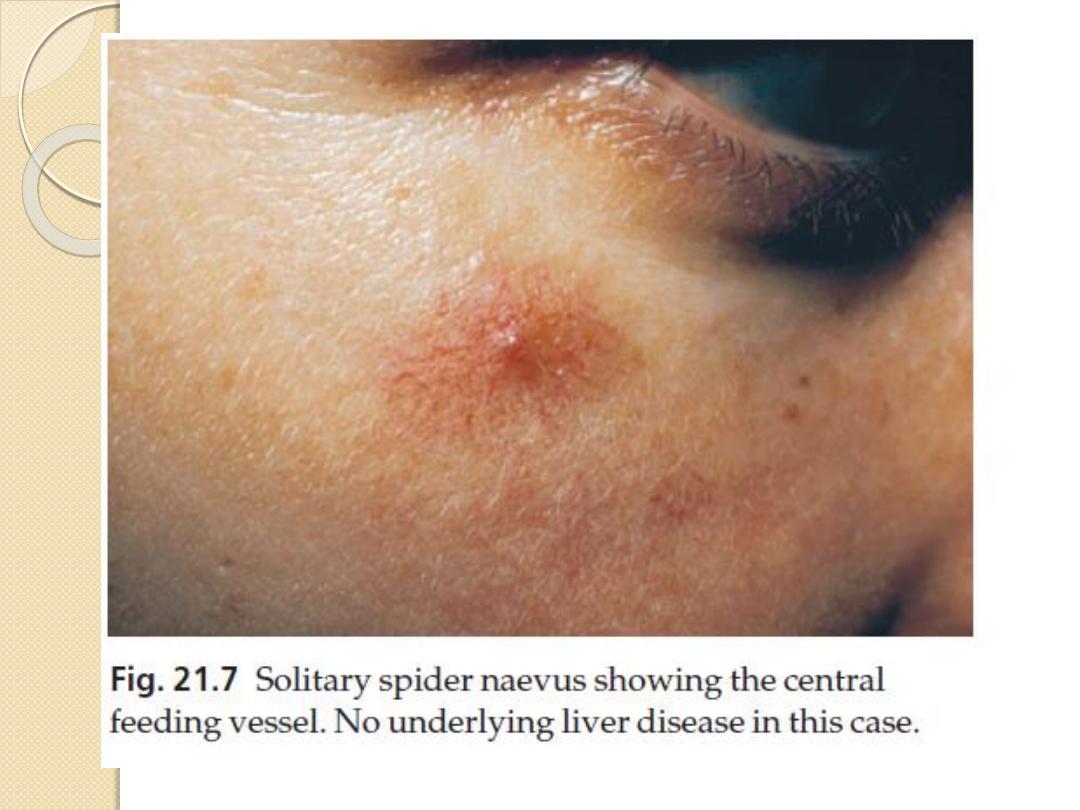

Spider naevi (These are often multiple in

chronic liver disease

Palmar erythema

White nails

These associate with hypoalbuminaemia

The skin in liver disease

Lichen planus and cryoglobulinaemia

with hepatitis C infection.

Polyarteritis nodosa with hepatitis B

infection.

Porphyria cutanea tarda .

Xanthomas With primary biliary

cirrhosis

Hair loss and generalized asteatotic

eczema may occur in alcoholics with

cirrhosis who have become zinc deficient.

The skin in renal disease

Pruritus and a generally dry skin.

Pigmentation A yellowish sallow colour

and pallor from anaemia.

Half-and-half nail The proximal half is

white and the distal half is pink or

brownish.

Perforating disorders Small papules in

which collagen or elastic fibres are being

extruded through the epidermis.

Pseudoporphyria

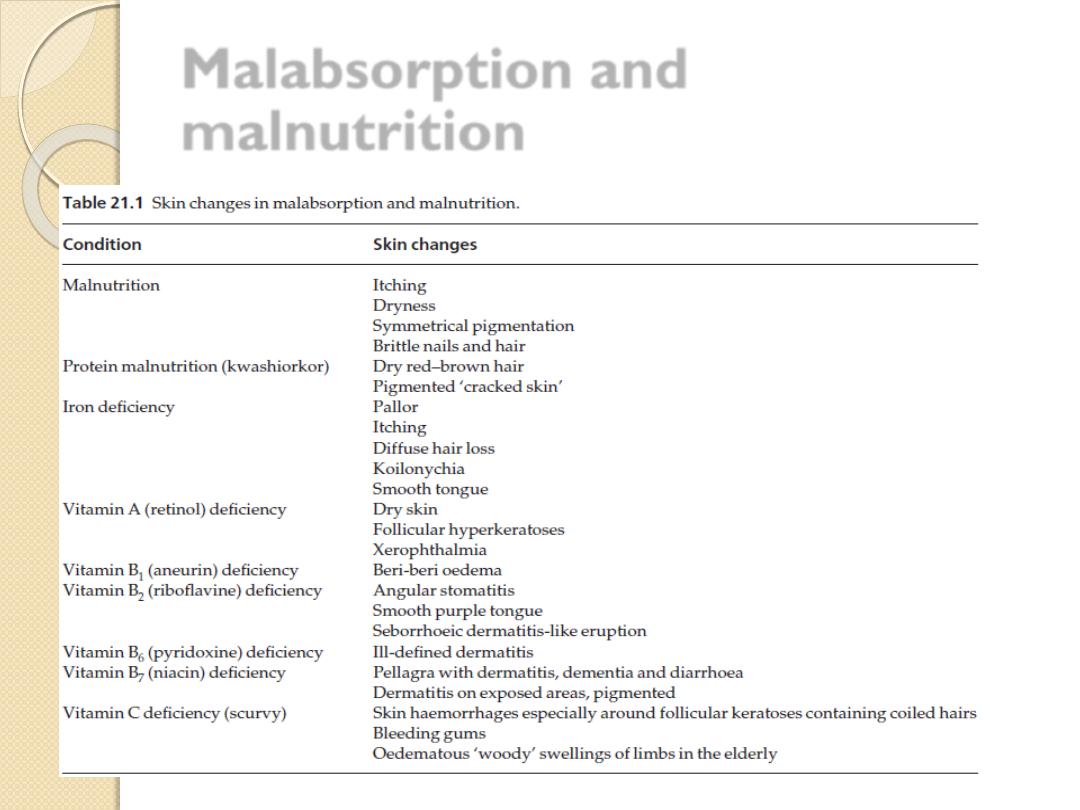

Malabsorption and

malnutrition

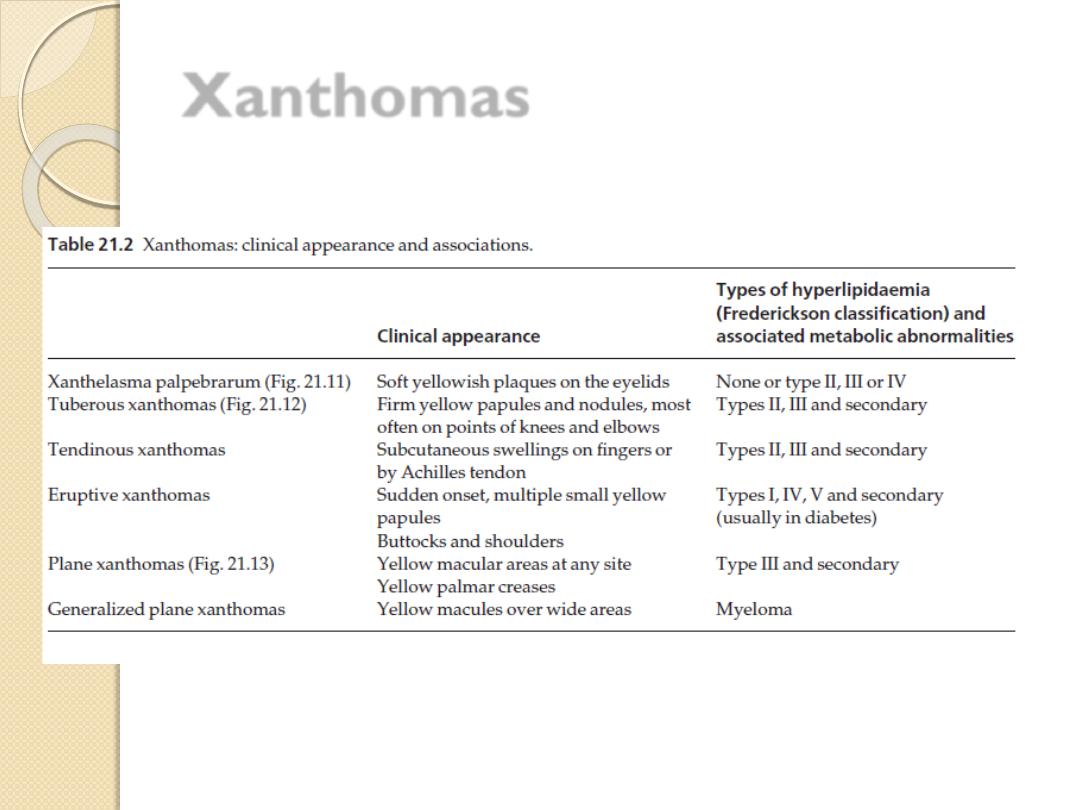

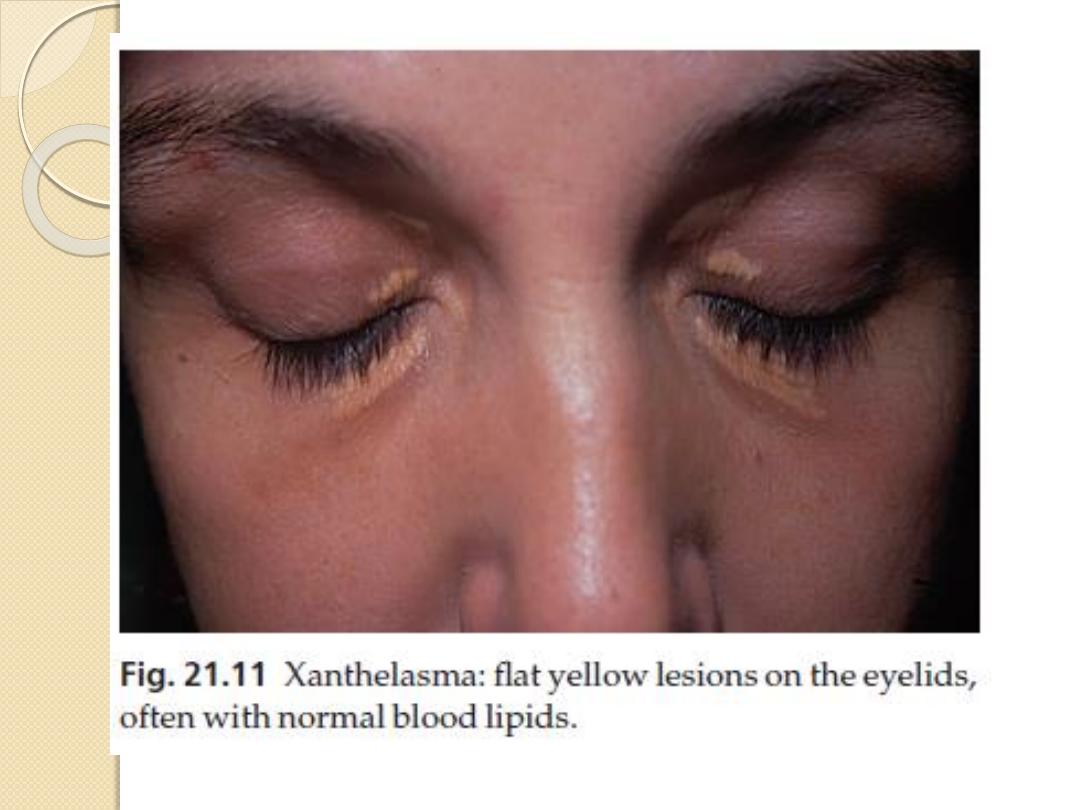

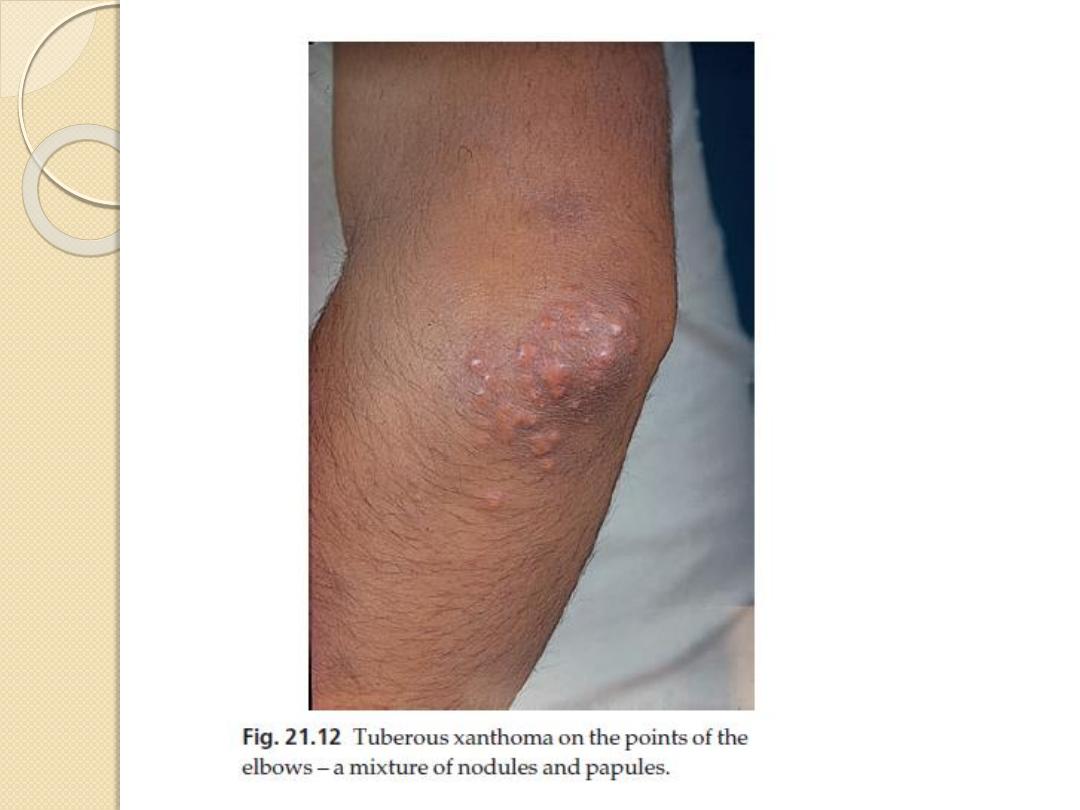

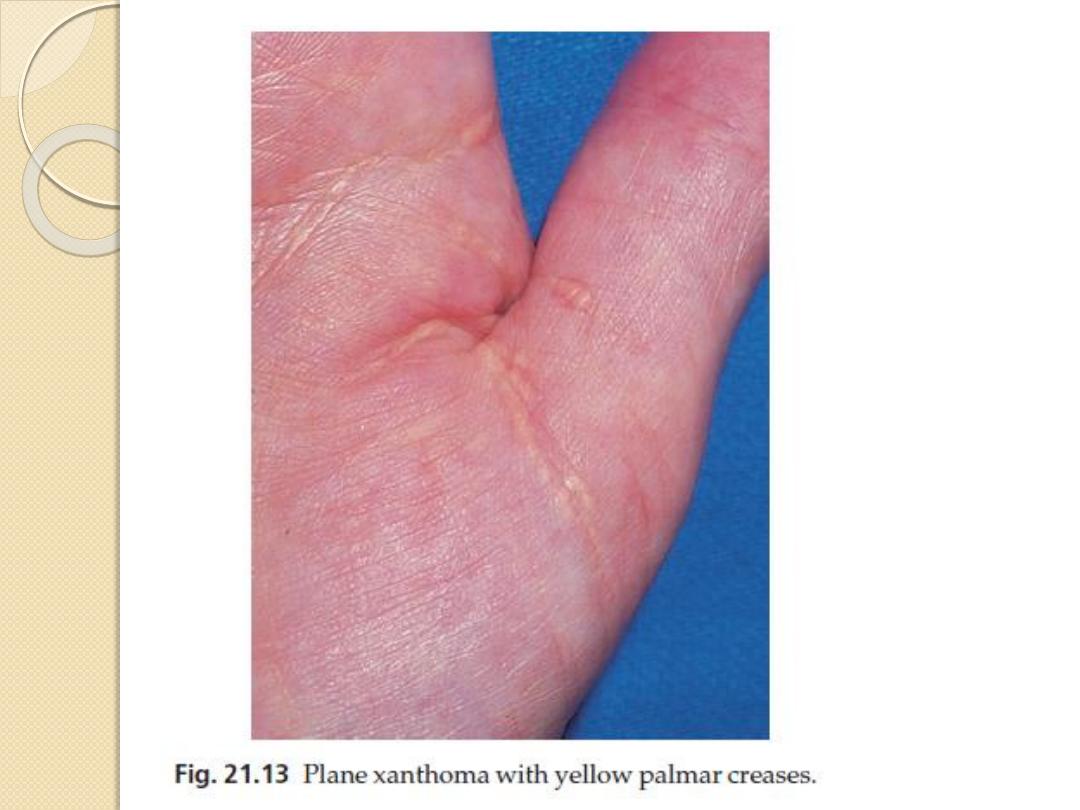

Xanthomas

Deposits of fatty material in the skin and

subcutaneous tissues (xanthomas) may provide

the first clue to important disorders of lipid

metabolism.

Primary hyperlipidaemias are usually genetic.

Secondary hyperlipidaemia can be found in a variety

of diseases including diabetes, primary biliary

cirrhosis, the nephrotic syndrome and

hypothyroidism.

Lipid-regulating drugs (e.g. statins and fibrates)

not only stop xanthomas from appearing, but they

also allow them to resolve.

Xanthomas

Generalized pruritus

Pruritus is a symptom with many causes, but not

a disease in its own right.

Itchy patients fall into two groups:

1.

those whose pruritus is caused simply by

surface causes (e.g. eczema, lichen planus and

scabies)

2.

those who may or may not have an internal

cause for their itching. These patients require a

detailed physical examination, including a careful

search for lymphadenopathy

Investigations including a full blood count, iron

status, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests,

thyroid function tests and a chest X-ray

Causes

Liver disease

Itching signals biliary obstruction.

It is an early symptom of primary biliary cirrhosis.

Colestyramine may help cholestatic pruritus, possibly

by promoting the elimination of bile salts.

Other treatments include naltrexone, rifampicin and

ultraviolet B.

Chronic renal failure

Ultraviolet B phototherapy, naltrexone or

administration of oral activated charcoal may help.

Iron deficiency

Treatment with iron may help the itching.

Causes

Polycythaemia

The itching here is usually triggered by a hot bath; it has a

curious pricking quality and lasts about an hour.

Thyroid disease

Itching and urticaria may occur in hyperthyroidism.

The dry skin of hypothyroidism may also be itchy.

Diabetes

Internal malignancy

The prevalence of itching in Hodgkin’s disease may be as high

as 30%.

It may be unbearable, yet the skin often looks normal.

Pruritus may occur long before other manifestations of the

disease.

Itching is uncommon in carcinomatosis.

Causes

Neurological disease

Paroxysmal pruritus has been recorded in multiple sclerosis

and in neurofibromatosis.

Brain tumours infiltrating the floor of the fourth ventricle may

cause a fierce persistent itching of the nostrils.

Diffuse scleroderma

may start as itching associated with increasing pigmentation

and early signs of sclerosis.

Itching is usually severe

The skin of the elderly may itch because it is too dry, or

because it is being irritated.

Pregnancy

Drugs

Treatment

Therapy is symptomatic and consists of

sedative antihistamines

skin moisturizers, and the avoidance of

rough clothing, overheating and

vasodilatation, including that brought on by

alcohol.

Ultraviolet B often helps all kinds of itching,

including the itching associated with chronic

renal and liver disease.

Local applications include calamine and

mixtures containing small amounts of

menthol or phenol

THE END

THANKS