Drug eruptions

Drug eruptions

• Almost any drug can cause a cutaneous

reaction

• Many inflammatory skin conditions can be

caused or exacerbated by drugs

Mechanisms

1. Non-allergic drug reactions

• result of overdosage, accumulation of drugs,

unwanted pharmaco-logical effects,

idiosyncratic, or a result of alterations of

ecological balance

• They are a normal biological effect

• often predictable

• affect many, or even all, patients taking the

drug at a sufficient dosage for a sufficient time

Mechanisms

2. Allergic drug reactions

• less predictable.

• occur in only a minority of patients receiving a drug

• occur even with low doses

• They are not a normal biological effect of the drug and

usually appear after the latent period required for

induction of an immune response

• Chemically related drugs may cross-react

• majority of allergic drug reactions are caused by cell-

mediated immune reaction

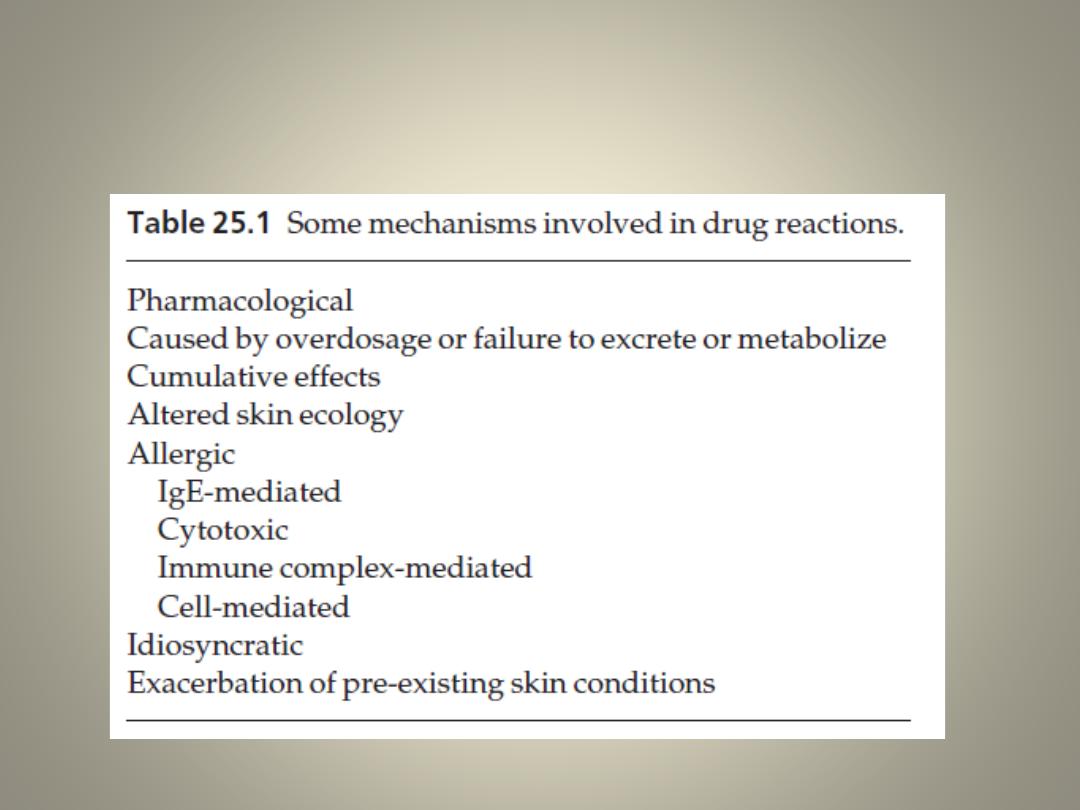

Some mechanisms involved in drug

reactions

Presentation

Antibiotics

Penicillins and sulphonamides

• are most commonly causing allergic reactions.

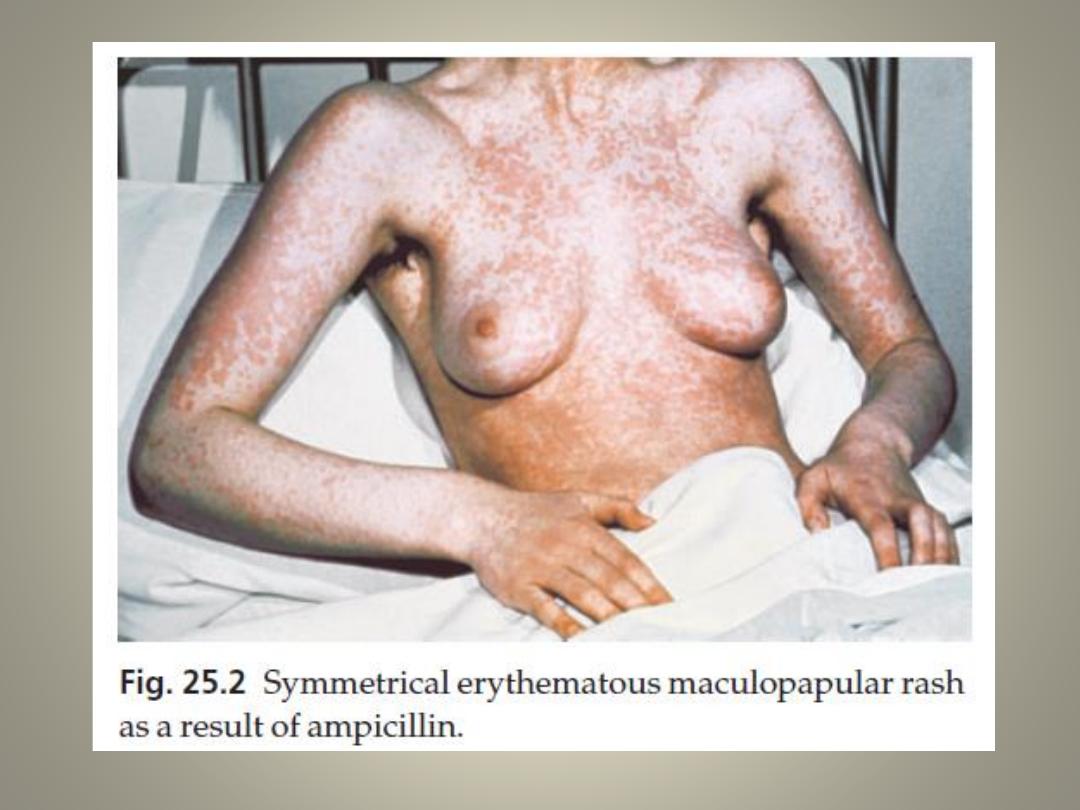

• These are often morbilliform but urticaria, erythema multiforme and fixed

eruptions are common too.

• DDx. Is viral infections as often associated with exanthems

• Most patients with infectious mononucleosis develop a morbilliform rash

if ampicillin is administered.

• Penicillin is a common cause of severe anaphylactic reactions, which can

be life-threatening.

Minocycline

• can accumulate in the tissues and produce a brown or grey colour in the

mucosa, sun-exposed areas or at sites of inflammation, as in the lesions of

acne

• hepatitis, worsen lupus erythematosus or elicit a transient lupus-like

syndrome

Oral contraceptives

• Reactions to these are less common now that

their hormonal content is small.

1. telogen effluvium

2. Melasma, hirsutism

3. erythema nodosum

4. acne

5. photosensitivity

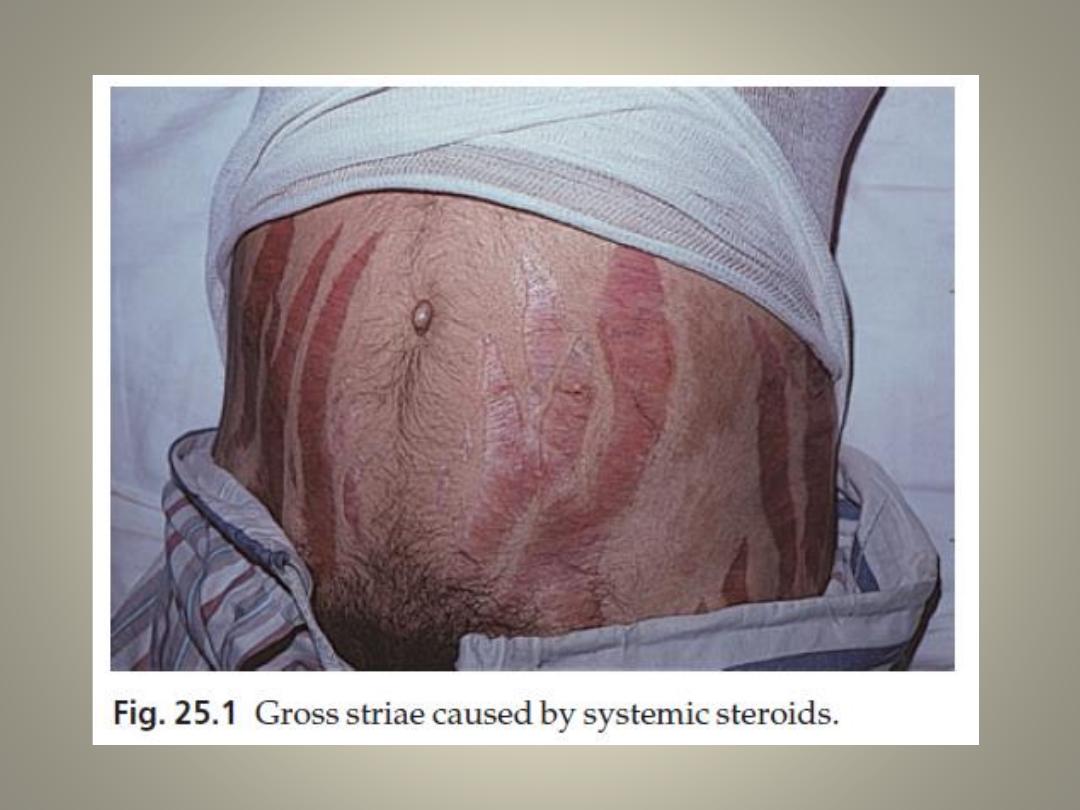

Steroids

Cutaneous side-effects from systemic steroids

include:

• a ruddy face

• cutaneous atrophy

• striae

• hirsutism

• an acneiform eruption

• a susceptibility to cutaneous infections, which

may be atypical

Anticonvulsants

Skin reactions to phenytoin, carbamazepine,

lamotrigine and phenobarbital are common

and include:

• erythematous, morbilliform, urticarial and

purpuric rashes.

• rarely TEN, erythema multiforme, exfoliative

dermatitis, DRESS syndrome and a lupus

erythematosuslike syndrome

Some common reaction patterns and

drugs that can cause them

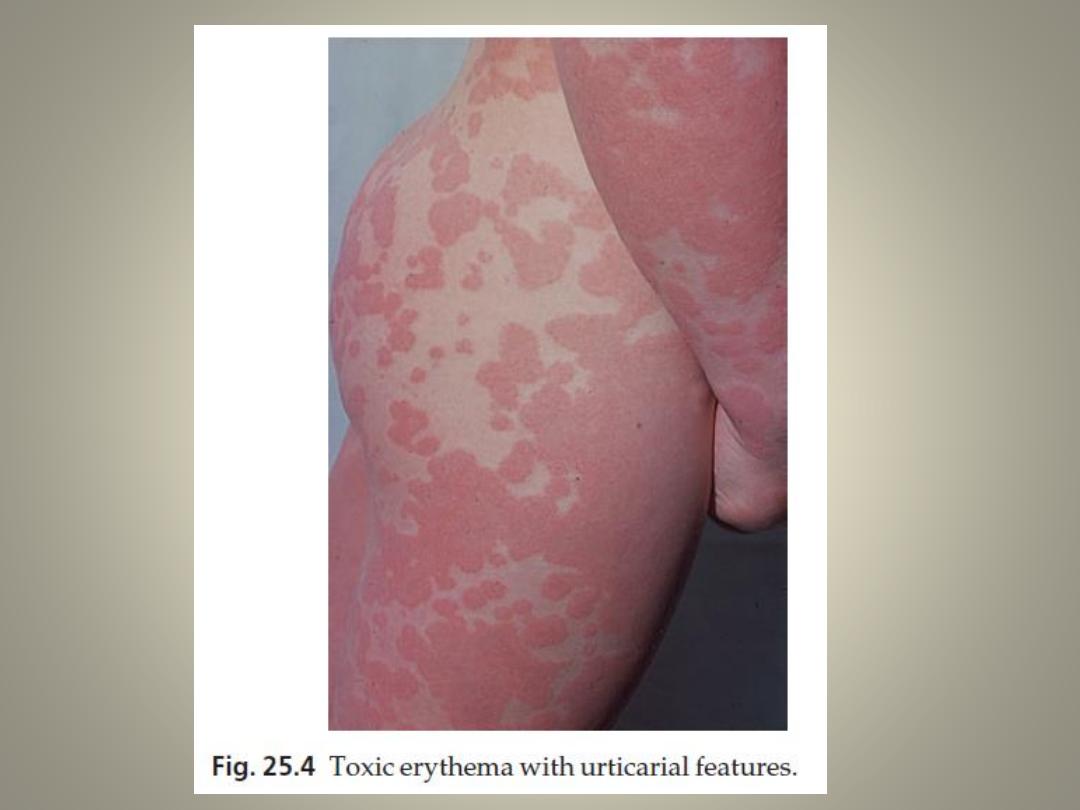

Toxic (reactive) erythema

• most common type of drug eruption

• looking like measles or scarlet fever, and

sometimes showing prominent urticarial or

erythema multiforme-like elements.

• Itching and fever may accompany the rash.

• Culprits include antibiotics (especially ampicillin),

sulphonamides and related compounds (diuretics

and hypoglycaemics) and barbiturates

Urticaria

• salicylates are the most common, often working non-

immunologically as histamine releasers.

• Antibiotics

• Urticaria may be part of a severe and generalized reaction

(anaphylaxis) that includes bronchospasm and collapse

Erythema multiforme and Stevens–Johnson syndrome

• Sulphonamides, barbiturates, lamotrigine and

phenylbutazone

Purpura

• Thiazides, sulphonamides, barbiturates and anticoagulants

Bullous eruptions

• also in Stevens–Johnson syndrome

• Vancomycin, lithium, diclofenac, captopril, furosemide and

amiodarone are associated with development of linear IgA

bullous disease

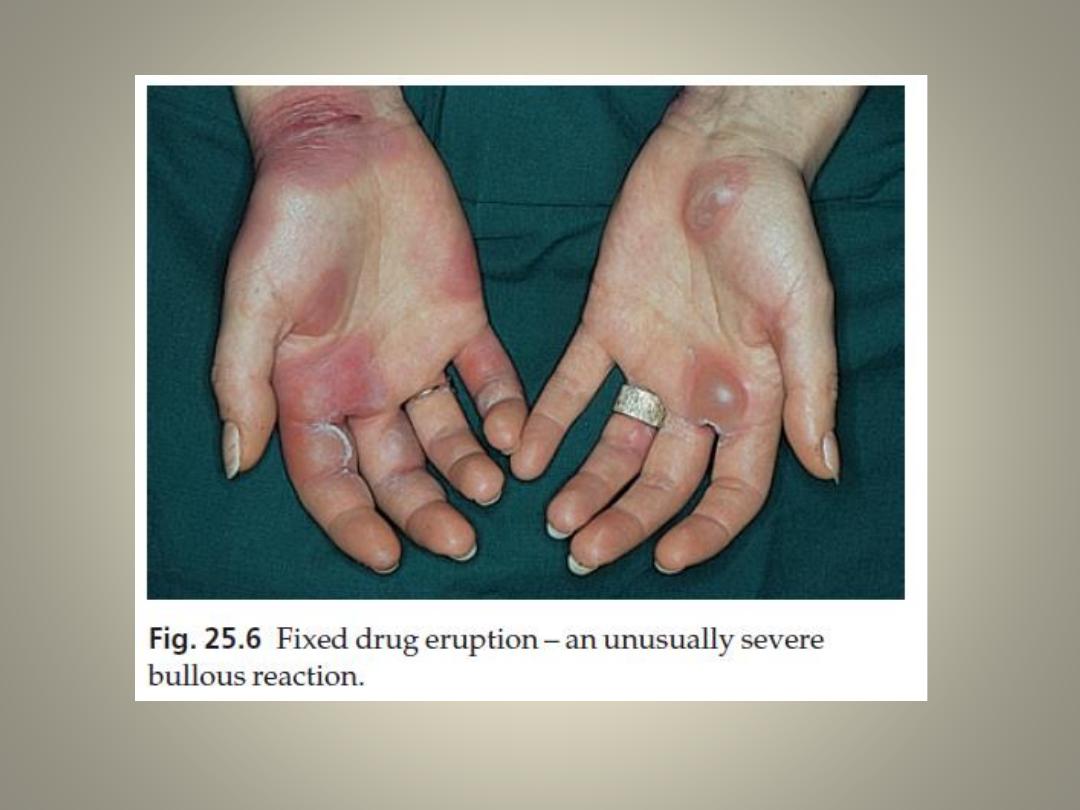

Fixed drug eruptions

• Round erythematous or purple, and sometimes bullous

plaques recur at the same site each time the drug is taken

• Pigmentation persists between acute episodes.

• The glans penis seems to be a favoured site.

• The causes of fixed drug eruptions in any country follow the

local patterns of drug usage

• Paracetamol is currently the most common offender in the

UK

• Trimethoprim-sulfa leads the list in the USA

• NSAIDs (including aspirin), antibiotics, systemic antifungal

agents and psychotropic drugs lie high on the list of other

possible offenders.

Acneiform eruptions

• Lithium, iodides, bromides

• oral contraceptives, androgens or glucocorticosteroids

• Antitub erculosis and anticonvulsant

Lichenoid eruptions

• These resemble lichen planus but mouth lesions are

uncommon and scaling and eczematous elements may

be seen.

• antimalarials, NSAIDs, gold, phenothiazines

Hair loss

• Retinoid

• cytotoxic agents

• oral contraceptive

Hypertrichosis

• dose-dependent effect of diazoxide, minoxidil

and ciclosporin

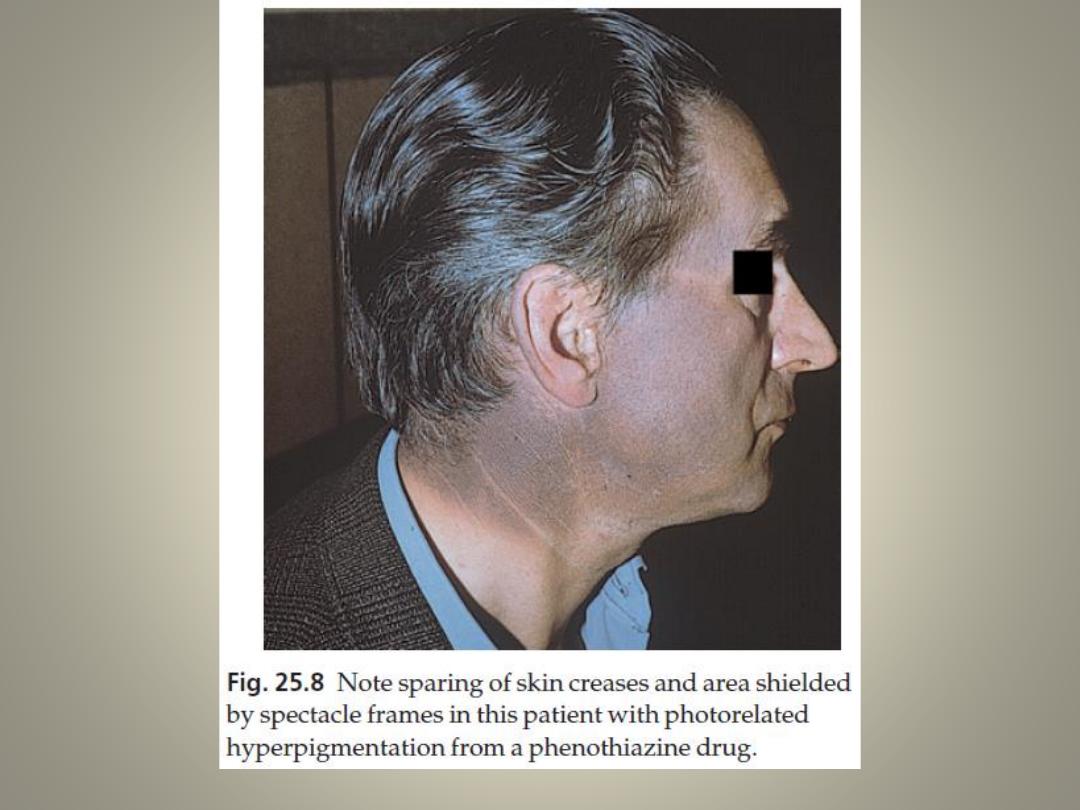

Pigmentation

• Melosma in oral contraceptive plus sun exposure

• Large doses of phenothiazines impart a blue–grey colour to

exposed areas

• clofazimine makes the skin red

• mepacrine turns the skin yellow

• minocycline turns areas of leg skin a curious greenish grey

colour

Xerosis

• oral retinoids

• nicotinic acid

• lithium

Course

• If an allergic reaction occurs during the first

course of treatment, it characteristically begins

late, often about the ninth day, or even after the

drug has been stopped

• In previously exposed patients the common

morbilliform allergic reaction starts 2–3 days after

the administration of the drug

• The speed with which a drug eruption clears

depends on the type of reaction and the rapidity

with which the drug is eliminated

Differential diagnosis

• Ranges over the whole subject of dermatology

• The general rule is never to forget the

possibility of a drug eruption when an atypical

rash is seen. Six vital questions should be

asked

The six vital questions to be asked

when a drug eruption is suspected.

1. Can you exclude a simple dermatosis (e.g. scabies or

psoriasis) and the known skin manifestations of an

underlying disorder (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus)?

2. Does the rash itself suggest a drug eruption (e.g. urticaria,

erythema multiforme)?

3. Does a past history of drug reactions correlate with

current prescriptions?

4. Was any drug introduced a few days or weeks before the

eruption appeared?

5. Which of the current drugs most commonly cause drug

eruptions (e.g. penicillins, sulphonamides, thiazides,

allopurinol, phenylbutazone)?

6. Does the eruption fit with a well-recognized pattern

caused by one of the current drugs (e.g. an acneiform rash

from lithium)?

Treatment

• The first approach is to withdraw the suspected drug,

accepting that several drugs may need to be stopped at

the same time.

• The decision to stop or continue a drug depends upon:

1. the nature of the drug

2. the necessity of using the drug for treatment

3. the availability of chemically unrelated alternatives

4. the severity of the reaction, its potential reversibility

5. the probability that the drug is actually causing the

reaction.

• Every effort must be made to correlate the

onset of the rash with prescription records.

• Often, but not always, the latest drug to be

introduced is the most likely culprit.

• Prick tests and in vitro tests for allergy are

unreliable to

• Re-administration, as a diagnostic test, is

usually unwise except when no suitable

alternative drug exists

Non-specific therapy depends upon the type of

eruption.

• In urticaria, antihistamines are helpful.

• In some reactions, topical or systemic

corticosteroids can be used, and applications

of calamine lotion may be soothing.

• Plasmapheresis and dialysis can be considered

in certain life-threatening situations

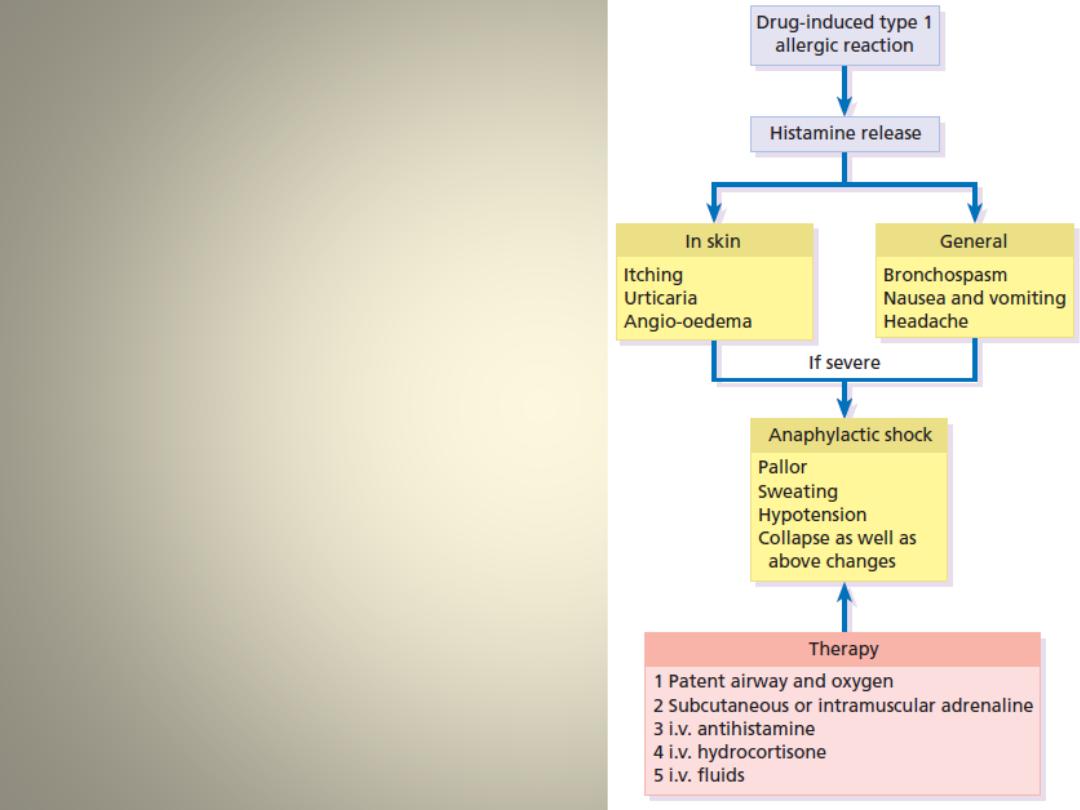

Anaphylactic reactions

• ensure that the airway is not compromised (e.g. oxygen, assisted

respiration or even emergency tracheostomy).

• One or more injections of adrenaline (epinephrine) (1 : 1000) 0.3–

0.5 mL should be given subcutaneously or intramuscularly in adults

• slow (over 1 min) intravenous injection of chlorphenamine

maleate (10–20 mg diluted in syringe with 5–10 mL blood).

• Although the action of intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg) is

delayed for several hours, it should be given to prevent further

deterioration in severely affected patients.

• Patients should be observed for 6 h after their condition is stable, as

late deterioration may occur.

• If an anaphylactic reaction is anticipated, patients should be taught

how to self-inject adrenaline, and may be given a salbutamol

inhaler to use at the first sign of the reaction

The cause, clinical

features and

treatment of

anaphylaxis.

Desensitization

• is seldom advisable or practical

The End