Authors: Professor Baha Diaa Moohee Alosy,

Departments of Pediatrics- Collage of Medicine.

University of Tikrit -IRAQ.

Neonatal Infection & / or sepsis

Objectives

❖

identify the approach of

Neonatal Infection

❖

Identify clinical

manifestation of

Neonatal

Infection

❖

Know the treatment for

Neonatal Infection

Background

Neonatal sepsis may be categorized as early onset (day of life 0-3) or late onset (day

of life 4 or later). Of neorns with early-onset sepsis, 85% present within 24 hours

(median age of onset 6 hours), 5% present at 24-48 hours, and a smaller percentage

present within 48-72 hours. Onset is most rapid in premature neonates

.

Early-onset sepsis is associated with acquisition of microorganisms from the mother

is more common in early-onset sepsis, whereas

meningitis and

are more common in late-onset

sepsis. Early-onset sepsis is 10 to 20 times more likely to occur

in premature, very low birthweight infants.

Etiology

The microorganisms most commonly associated with early-

onset infection include the following

[1]

:

Group B Streptococcus (GBS)

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

Late-onset sepsis occurs at 4-90 days of life and is

acquired from the environment. Organisms that have

been implicated in late-onset sepsis include the

following:

•

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

•

E coli

•

Klebsiella

•

Enterobacter

•

Candida

•

GBS

•

Serratia

•

Acinetobacter

•

Anaerobes

Early-onset neonatal sepsis

Risk factors implicated in neonatal sepsis reflect the

level stress and illness experienced by the fetus at

delivery, as well as the hazardous uterine

environment surrounding the fetus before delivery.

The most common risk factors associated with early-

onset neonatal sepsis include, but are not limited to,

the following:

Maternal GBS colonization (particularly in the setting

of inadequate prophylactic treatment)

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

Preterm rupture of membranes

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Premature birth

Maternal urinary tract infection (UTI)

Maternal fever greater than 38ºC (100.4ºF)

Other factors that are associated with or predispose to

early-onset sepsis include the following :

Low Apgar score (< 6 at 1 or 5 minutes)

Poor prenatal care

Poor maternal nutrition

Low socioeconomic status

Black mother

History of recurrent abortion

Maternal substance abuse

Low birth weight

Difficult delivery

Birth asphyxia

Meconium staining

Congenital anomalies

•

Late-onset sepsis is associated with the

following risk factors

[20]

:

•

Prematurity

•

Central venous catheterization (duration >10

days)

•

Urinary catheterization

•

Chronic mechanical ventilation

•

Failure to advance enteral feeding

•

nasal cannula or continuous positive airway

pressure (CPAP)

•

Use of H

2

-receptor blocker or proton pump

inhibitor (PPI)

•

Gastointestinal tract pathology

•

Meningitis

•

The principal pathogens in neonatal meningitis

are GBS (36% of cases), E coli (31%),

and Listeria species (5%-10%). Other organisms

that may cause meningitis include the following:

•

S pneumoniae

•

S aureus

•

S epidermidis

•

H influenzae

•

Pseudomonas species

•

Klebsiella species

•

Serratia species

•

Enterobacter species

•

Proteus species

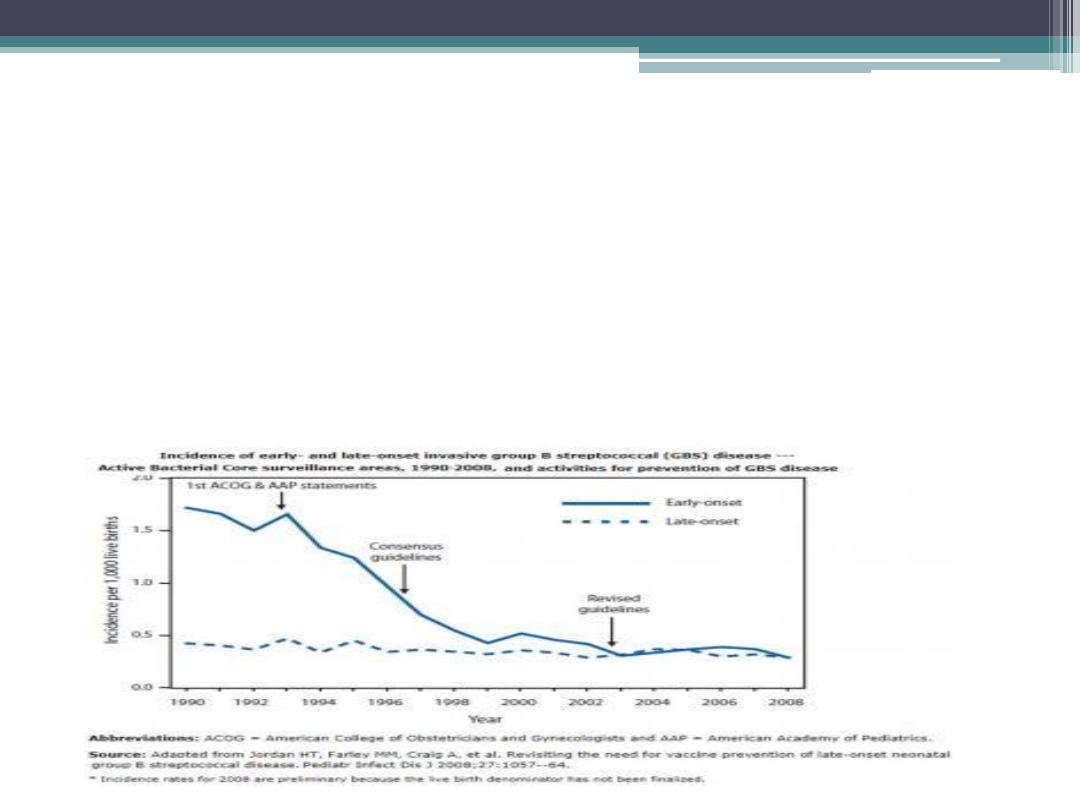

Epidemiology

•

The incidence of culture-proven early-onset

sepsis in the United States is approximately 0.3-2

per 1000 live births. Of the 7%-13% of neonates

who are evaluated for neonatal sepsis, only 3%-

8% of those screened will have culture-proven

sepsis.

Age-, race-, and sex-related demographics

•

Premature infants have an increased incidence of sepsis, with a

significantly higher occurrence in infants with a birth weight lower than

1500 g (11-22.7 per 1000 live births) than in infants born at 37 weeks or

later (0.3-0.98 per 1000 live births).

•

Black infants have an increased incidence of GBS disease and late-onset

sepsis. This is observed even after other risk factors such as low birth

weight and younger maternal age have been controlled

•

Prognosis

➢

With early diagnosis and treatment of neonatal sepsis, most term infants

will not experience associated long-term health problems. However, if

early signs or risk factors are missed, mortality increases. Residual

neurologic damage occurs in 15%-30% of neonates with septic meningitis.

➢

Mortality from neonatal sepsis may be as high as 50% for infants who are

not treated. Infection is a major cause of mortality during the first month

of life, contributing to 13%-15% of all neonatal deaths. Low birth weight

and gram-negative infection are associated with worse outcomes.

➢

Neonatal meningitis occurs in 2-4 cases per 10,000

live births and contributes significantly to mortality

from neonatal sepsis; it is responsible for 4% of all

neonatal deaths.

➢

In preterm infants who have had sepsis, impaired

neurodevelopment is a concern. Proinflammatory

molecules may negatively affect brain development

in this patient population. In a large study of 6093

premature infants who weighed less than 1000 g at

birth, preterm infants with sepsis who did not have

meningitis had higher rates of cerebral palsy (odds

ratio [OR] 1.4-1.7), developmental delay (OR 1.3-

1.6), and vision impairment (OR 1.3-2.2) as well as

other neurodevelopmental disabilities than infants

who did not have sepsis

Neonatal Sepsis Clinical Presentation

•

History

An awareness of the many risk factors associated

with neonatal sepsis prepares the clinician for

early identification and effective treatment,

thereby reducing morbidity and mortality.

Among these risk factors are the following:

•

Maternal group B Streptococcus (GBS) status

•

Prolonged and/or premature rupture of

membranes (PPROM)

•

Premature delivery

•

Chorioamnionitis

1.

Signs

1. Respiratory distress

(90%)

2. Apnea

4. Flaring or

grunting

5. Irregular

respirations

2. Temperature instability

sustained over 1 hour

(30%)

1. Newborn

Temperature < 97

F (36 C)

2. Newborn

Temperature >

99.6 F (37 C)

3. Gastrointestinal

symptoms

4. Neurologic

3. Tachycardia

1. Pallor or skin

or

3. Cold or clammy

1.

Labs

suggestive of

Count

1. Decreased

below 5000

/mm3

2. Increased

above

25000

/mm3

(ANC) < 1000

/mm3

3. Bands to total

ratio > 0.2

4. Immature to

mature

ratio > 0.2

(positive in 5-10% of

1. Indicated for

1. Indications

2. Specific Tests

1. Indicated for late-

perinatal period

(age <3 days old)

Differential Diagnoses

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

▪

Metabolic Disorders

Pediatric Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

Pediatric Congestive Heart Failure

•

Management: General

▫ Monitor infant for signs of

▫ Antibiotic indications (contrast

with observation only)

Symptomatic infants

Asymptomatic infants with

>2 risk factors (see above)

▫ Continue monitoring and

antibiotics for 48 to 72 hours

Indications to continue

antibiotics 14 to 21 days

Symptomatic newborn

positive

Discontinue antibiotics and

monitoring if

s negative at 48

to 72 hours and

No signs of

on

examination

▫ Signs of

with negative

culture

Consider

infection

•

Management: Antibiotics for

Early Onset (age <1 week)

▫ Bacterial spectrum

(not

common)

Listeria (rare in United

States)

▫ Primary Antibiotic Protocol

(

dose often used

empirically)

: 50 mg/kg/dose IV

or IM q12 hours

: 100

mg/kg/dose IV or IM q12

hours

Gestation <28 weeks: 2.5

mg/kg/dose IV/IM q24

hours

Gestation <34 weeks: 2.5

mg/kg/dose IV/IM q18

hours

Gestation >34 weeks: 2.5

mg/kg/dose IV/IM q12

hours

▫ Alternative Options

Alternative Protocol 1

(dosed as

above)

50

mg/kg/dose IV or IM q12

hours

Alternative Protocol 2

(dosed as

above)

50 mg/kg IV

or IM q24 hours

•

Management: Antibiotics

for Late Onset (age 1-4

weeks)

▫ Coverage broadened over

early onset

epidermidis

▫ )

▫ Antibiotic Dosing for infant over 7 days old

(the higher dose in possible

Weight <2 kg: 25-50 mg/kg/dose IV or IM q8 hours

Weight >2 kg: 25-50 mg/kg/dose IV or IM q6 hours

Gestation <37 weeks: 2.5 mg/kg/dose IV/IM q12 hours

Gestation >37 weeks: 2.5 mg/kg/dose IV/IM q8 hours

▫ Primary Protocol 1

(dosed as above)

50 mg/kg/dose IV or IM q8 hours

▫ Primary Protocol 2

(dosed as above)

75 mg/kg/dose IV or IM q24 hours

▫ Alternative Protocol

(dosed as above)

(dosed as above)

•

Prevention

Rupture of Membranes GBS Prophylaxis

▫ Routine Group B Strep Screening in pregnancy (36 weeks

1 )

Klinger G, Levy I, Sirota L, et al, for the Israel Neonatal Network. Epidemiology and risk factors for early onset sepsis among very -low-birthweight infants. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 2009 Jul. 201 (1 ):38.e1-6.

2)

v an den Hoogen A, Gerards LJ, Verboon-Maciolek MA, Fleer A, Krediet TG. Long-term trends in the epidemiology of neonatal sepsis and antibiotic susceptibility of

causative agents. Neonatology. 2010. 97 (1):22-8.

3)

[Guideline] Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ, for the Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Im munization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease

Con trol and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 Nov 19. 59 (RR-

1 0):1-36.

4)

Ber ardi A, Rossi C, Spada C, et al, for the GBS Prevention Working Group of Em ilia-Rom agna. Strategies for preventing early-onset sepsis and for managing neonates at-

r isk: wide variability across six Western countries. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019 Sep. 32 (18):3102-8.

5)

Lin FY, Weisman LE, Azimi P, et al. Assessment of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of early-onset group B Streptococcal disease. Pediatr Infect Dis

J. 2 011 Sep. 30 (9):759-63.

6)

W eston EJ, Pondo T, Lewis MM, et al. The burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005-2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011 Nov. 30 (11):937-

4 1 .

7)

Mor ales WJ, Dickey SS, Bornick P, Lim DV. Change in antibiotic resistance of group B streptococcus: impact on intrapartum management. Am J ObstetGynecol. 1999

A ug. 181 (2):310-4.

8)

Strunk T, Richmond P, Simmer K, Currie A, Levy O, Burgner D. Neonatal immune responses to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007 Aug. 20

(4 ):370-5.

9)

Pow er Coombs MR, Kronforst K, Levy O. Neonatal host defense against Staphylococcal infections. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013. 2013:826303.

10)

Sr inivasan L, Kirpalani H, Cotten CM. Elucidating the role of genomics in neonatal sepsis. Semin Perinatol. 2015 Dec. 39 (8):611-6.

11)

Gr oer MW, Gregory KE, Louis-Jacques A, Thibeau S, Walker WA. The very low birth weight infant microbiome and childhood health. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today.

2 015 Dec. 105 (4):252-64.

12)

Koen ig JM, Yoder MC. Neonatal neutrophils: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Perinatol. 2004 Mar. 31 (1):39-51.

13)

W einberg AG, Rosenfeld CR, Manroe BL, Browne R. Neonatal blood cell count in health and disease. II. Values for lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils. J Pediatr.

1 985 Mar. 1 06 (3):462-6.

14)

La ndor M. Maternal-fetal transfer of immunoglobulins. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995 Apr. 74 (4):279-83; quiz 284.

15)

Gr iffiths PD, Stagno S, Pass RF, Smith RJ, Alford CA Jr. Congenital cytomegalov irus infection: diagnostic and prognostic significance of the detection of specific

im munoglobulin M antibodies in cord serum. Pediatrics. 1982 May. 69 (5):544-9.

16)

Koh ler PF. Maturation of the human complement system. I. Onset time and sites of fetal C1q, C4, C3, and C5 synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar. 52 (3):671-7.

17)

Stocker J, Dehner L, eds. Pediatric Pathology. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1992.

18)

A rnon S, Litmanovitz I. Diagnostic tests in neonatal sepsis. Curr Opin Infect Dis . 2008 Jun. 21 (3):223-7 .

19)

Sim onsen KA, Anderson-Berry AL, Delair SF, Davies HD. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014 Jan. 27 (1):21-47.

20)

Graham PL 3rd, Begg MD, Larson E, Della-Latta P, Allen A, Saiman L. Risk factors for late onset gram-negative sepsis in low birth weight infants hospitalized in the

n eonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Feb. 25 (2):113-7.

21)

Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, et al, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Early

on set neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics. 2011 May. 127 (5):817-26.

22)

Am erican Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book 2003: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003.

1 1 7-123, 237-43, 561-73, 584-91.

23)

Am erican Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book 2018-2021: Report of the Committee on Infectious Dis eases. 31st ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics;

2 018.

24)

Am erican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee opinion no. 485: Prevention of early-onset group B

str eptococcal disease in newborns (reaffirmed in 2016). Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr. 117 (4):1019-27.

25)

[Guideline] Schrag S, Gorwitz R, Fultz-Butts K, SchuchatA. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep.

2 002 Aug 16. 51 (RR-11):1-22.

26)

Mu khopadhyay S, Lieberman ES, Puopolo KM, Riley LE, Johnson LC. Effect of early-onset sepsis evaluations on in-hospital breastfeeding practices among asymptomatic

term neonates. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 Apr. 5 (4):203-10.

27)

Kermorvant-Duchemin E, Laborie S, Rabilloud M, Lapillonne A, Claris O. Outcome and prognostic factors in neonates with septic shock.Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008

Ma r. 9 (2):186-91.

[Medline]

.