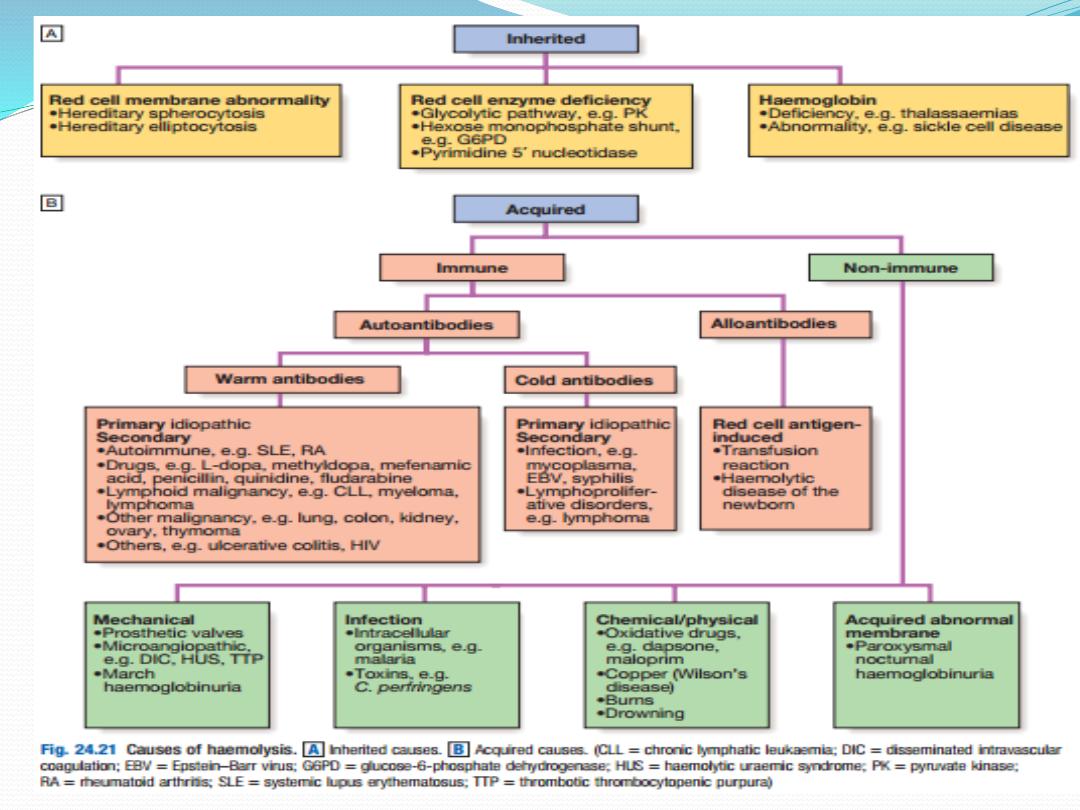

Haemolytic anaemia

Haemolysis indicates that there is shortening of the

normal red cell lifespan of 120 days. There are many

causes. To compensate, the bone marrow may increase

its output of red cells six to eight fold by increasing the

proportion of red cells produced, expanding the

volume of active marrow, and releasing reticulocytes

prematurely. Anaemia only occurs if the rate of

destruction exceeds this increased production rate.

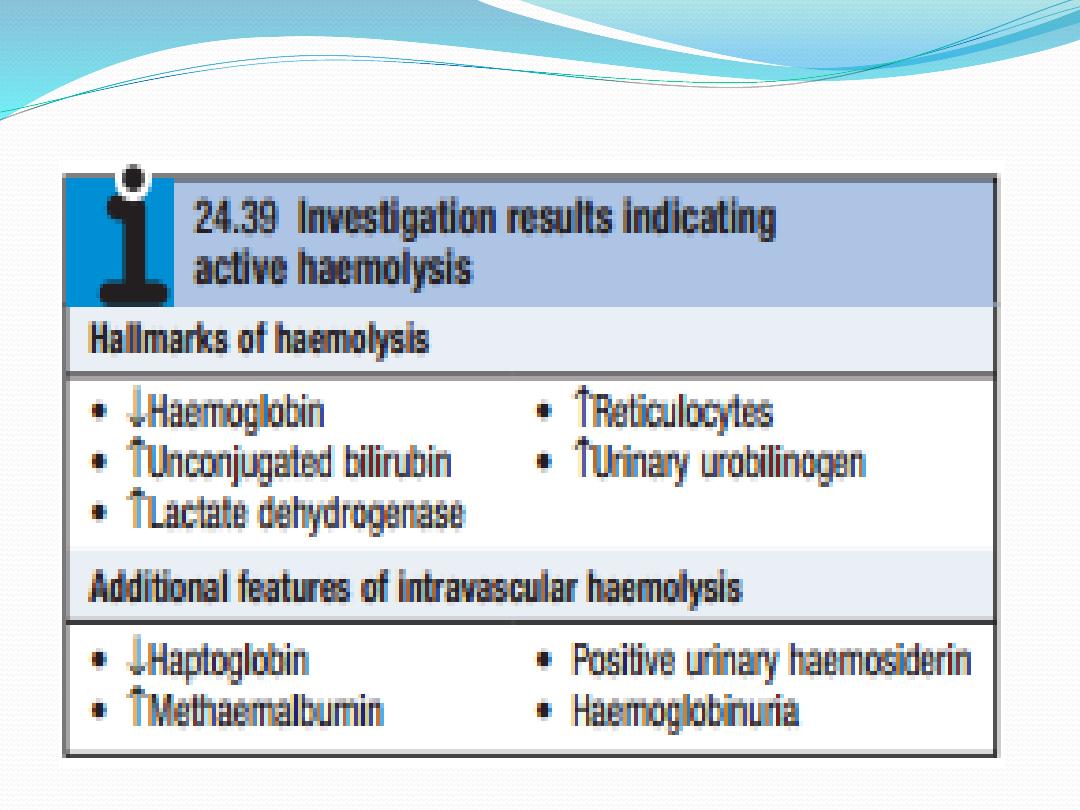

Red cell destruction overloads pathways for haemoglobin

breakdown in the liver , causing a modest rise in

unconjugated bilirubin in the blood and mild jaundice.

Increased reabsorption of urobilinogen from the gut results

in an increase in urinary urobilinogen . Red cell destruction

releases LDH into the serum. The bone marrow

compensation results in a reticulocytosis, and sometimes

nucleated red cell precursors appear in the blood.

Increased proliferation of the bone marrow can result in a

thrombocytosis, neutrophilia and, if marked, immature

granulocytes in the blood, producing a leucoerythroblastic

blood film.

The appearances of the red cells may give an

indication of the likely cause of the haemolysis:

• Spherocytes are small, dark red cells which suggest

autoimmune haemolysis or hereditary spherocytosis.

• Sickle cells suggest sicklecell disease.

• Red cell fragments indicate microangiopathic

haemolysis.

The compensatory erythroid hyperplasia may give rise to

folate deficiency, with megaloblastic blood features.

The differential diagnosis of haemolysis is determined by

the clinical scenario in combination with the results of

blood film examination and Coombs testing for antibodies

directed against red cells.

Extravascular haemolysis

Physiological red cell destruction occurs in the

reticuloendothelial cells in the liver or spleen, so

avoiding free haemoglobin in the plasma. In most

haemolytic states, haemolysis is predominantly

extravascular.To confirm the haemolysis, patients’ red

cells can be labelled with 51 chromium. When re-

injected, they can be used to determine red cell

survival; when combined with body surface

radioactivity counting, this test may indicate whether

the liver or the spleen is the main source of red cell

destruction. However, it is seldom performed in

clinical practice.

Intravascular haemolysis

Less commonly, red cell lysis occurs within the blood

stream due to membrane damage by complement (ABO

transfusion reactions, paroxysmal nocturnal haemo

globinuria), infections (malaria, Clostridium perfringens),

mechanical trauma (heart valves, DIC) or oxidative

damage (e.g. drugs such as dapsone and maloprim).

When intravascular red cell destruction occurs, free hae-

moglobin is released into the plasma. Free haemoglobin

is toxic to cells and binding proteins have evolved to

minimise this risk. Haptoglobin is an α2globulin produced

by the liver, which binds free haemoglobin,

resulting in a fall in its levels during active haemolysis.

Once haptoglobins are saturated, free haemoglobin is

oxidised to form methaemoglobin, which binds to

albumin, in turn forming methaemalbumin, which can be

detected spectrophotometrically in the Schumm’s test.

Methaemoglobin is degraded and any free haem is bound

to a second binding protein called haemopexin. If all the

protective mechanisms are saturated, free haemoglobin

may appear in the urine (haemoglobinuria). When

fulminant, this gives rise to black urine, as in severe

falciparum malaria infection . In smaller amounts,renal

tubular cells absorb the haemoglobin, degrade it and store

the iron as haemosiderin. When the tubular cells are

subsequently sloughed into the urine, they give rise to

haemosiderinuria, which is always indicative of

intravascular haemolysis.

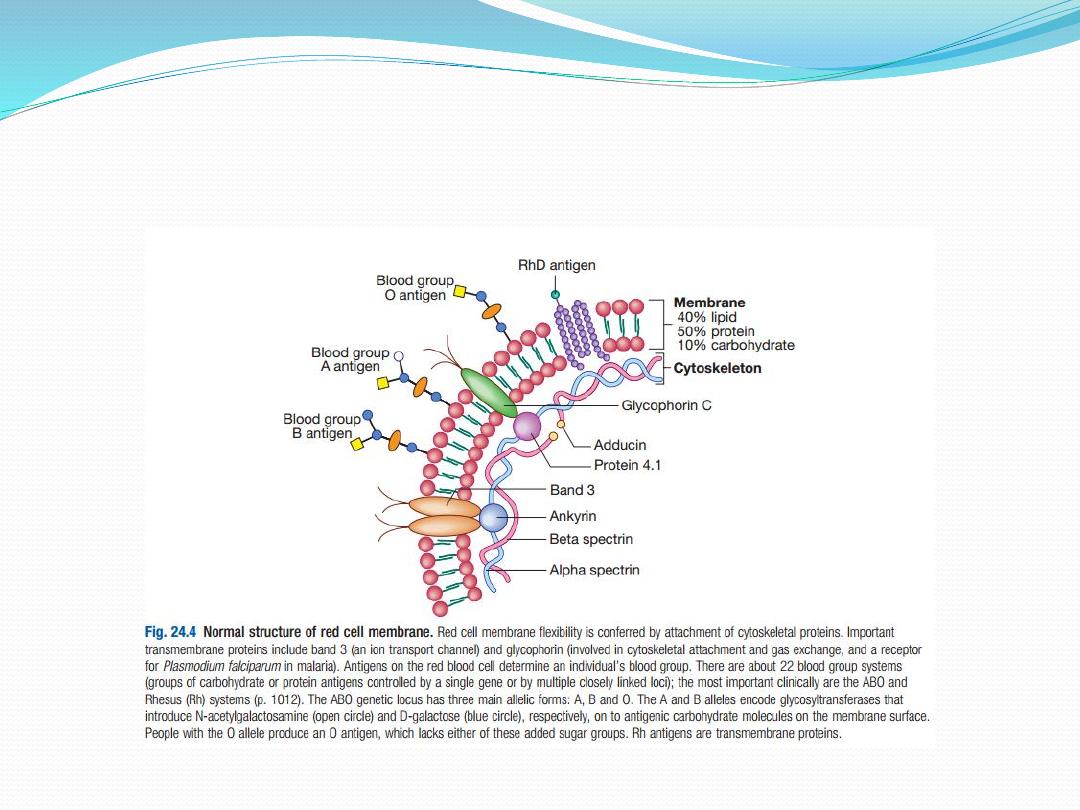

Red cell membrane defects

The basic structure is a cytoskeleton ‘stapled’ on to the

lipid bilayer by special protein complexes. This

structure ensures great deformability and elasticity;

the red cell diameter is 8 µm but the narrowest

capillaries in the circulation are in the spleen,

measuring just 2 µm in diameter. When the normal

red cell structure is disturbed, usually by a quantitative

or functional deficiency of one or more proteins in the

cytoskeleton, cells lose their elasticity. Each time such

cells pass through the spleen, they lose membrane

relative to their cell volume. This results in an increase

in mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC),

abnormal cell shape and reduced red cell survival

due to extravascular haemolysis.

Hereditary spherocytosis

This is usually inherited as an

autosomal dominant

condition, although 25% of cases have no family

history and represent new mutations. The incidence is

approximately

1 : 5000

in developed countries but this

may be an underestimate, since the disease may

present de novo in patients aged over 65 years and is

often discovered as a chance finding on a blood count.

The most common abnormalities are

deficiencies of

beta spectrin or ankyrin

.

The severity of spontaneous haemolysis varies. Most

cases are associated with an asymptomatic

compensated chronic haemolytic state with

spherocytes present on the blood film, a reticulo -

cytosis and mild hyperbilirubinaemia. Pigment

gallstones are present in up to 50% of patients and

may cause symptomatic cholecystitis. Occasional cases

are associated with more severe haemolysis; these may

be due to coincidental polymorphisms in alpha

spectrin or coinheritance of a second defect involving a

different protein.

The clinical course may be complicated by crises:

•

A haemolytic crisis

occurs when the severity of

haemolysis increases; this is rare, and usually

associated with infection.

•

A megaloblastic crisis

follows the development of

folate deficiency; this may occur as a first

presentation of the disease in pregnancy.

•

An aplastic crisis

occurs in association with

parvovirus B19 infection. Parvovirus causes

a common exanthem in children, but if individuals

with chronic haemolysis become infected, the virus

directly invades red cell precursors and temporarily

switches off red cell production. Patients present

with severe anaemia and a low reticulocyte count.

Investigations

The patient and other family members should be

screened

for features of compensated haemolysis . This may be all

that is required to confirm the diagnosis. Haemoglobin

levels are variable, depending on the degree of

compensation. The blood film will show

spherocytes but

the direct Coombs test is negative

, excluding immune

haemolysis. An

osmotic fragility test

may show increased

sensitivity to lysis in hypotonic saline solutions but is

limited by lack of sensitivity and specificity. More specific

flow cytometric tests

, detecting binding of eosin5-

maleimide to red cells, are recommended in borderline

cases.

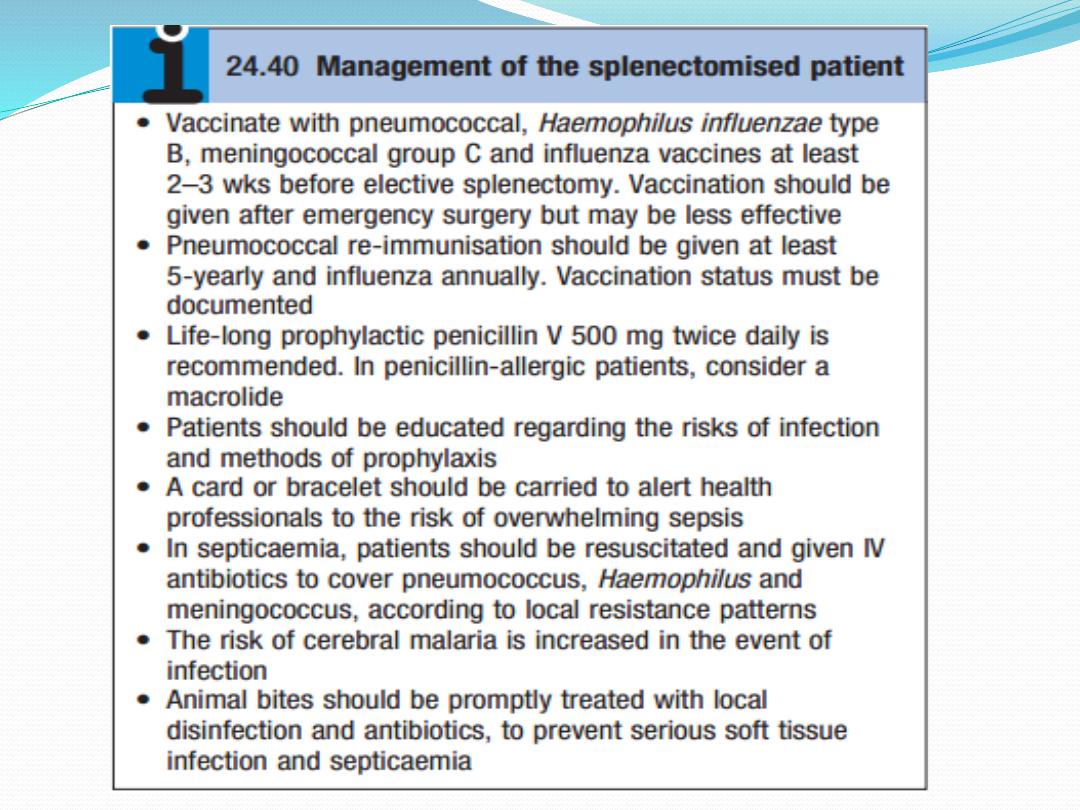

Management

Folic acid prophylaxis

, 5 mg daily, should be given for

life. Consideration may be given to

splenectomy

,

which

improves but does not normalise red cell survival.

Potential indications include moderate to severe

haemolysis with complications (anaemia and

gallstones), although splenectomy should be delayed

until after 6 years of age in view of the risk of sepsis.

Acute, severe haemolytic crises require transfusion

support, but blood must be crossmatched carefully

and transfused slowly as haemolytic transfusion

reactions may occur.

Hereditary elliptocytosis

This term refers to a heterogeneous group of disorders

that produce an increase in elliptocytic red cells on the

blood film and a variable degree of haemolysis. This is

due to a functional abnormality of one or more anchor

proteins in the red cell membrane, e.g.

alpha spectrin or

protein 4.1

. Inheritance may be

autosomal dominant or

recessive.

Hereditary elliptocytosis is less common than

hereditary spherocytosis in Western countries, with an

incidence of

1/10 000

, but is more common in equatorial

Africa and parts of Southeast Asia.

The clinical course is variable and depends upon the

degree of membrane dysfunction caused by the

inherited molecular defect(s); most cases present as an

asymptomatic blood film abnormality, but occasional

cases result in neonatal haemolysis or a chronic

compensated haemolytic state.

Management of the

latter is the same as for hereditary spherocytosis

.

A characteristic variant of hereditary elliptocytosis

occurs in Southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia and

Papua New Guinea, with stomatocytes and ovalocytes

in the blood. This has a prevalence of up to 30% in

some communities because it offers relative protection

from malaria and thus has sustained a high gene

frequency. The blood film is often very abnormal and

immediate differential diagnosis is broad.

Red cell enzymopathies

The mature red cell must produce energy via ATP to

maintain a normal internal environment and cell volume

whilst protecting itself from the oxidative stress presented

by oxygen carriage. Anaerobic glycolysis via the Embden–

Meyerhof pathway generates ATP, and the hexose

monophosphate shunt produces nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and glutathione to

protect against oxidative stress. The impact of functional or

quantitative defects in the enzymes in these pathways

depends upon the importance of the steps affected and the

presence of alternative pathways.

In general, defects in the

hexose monophosphate shunt pathway result in periodic

haemolysis precipitated by episodic oxidative stress,

whilst those in the Embden–Meyerhof pathway result

in shortened red cell survival and chronic haemolysis.

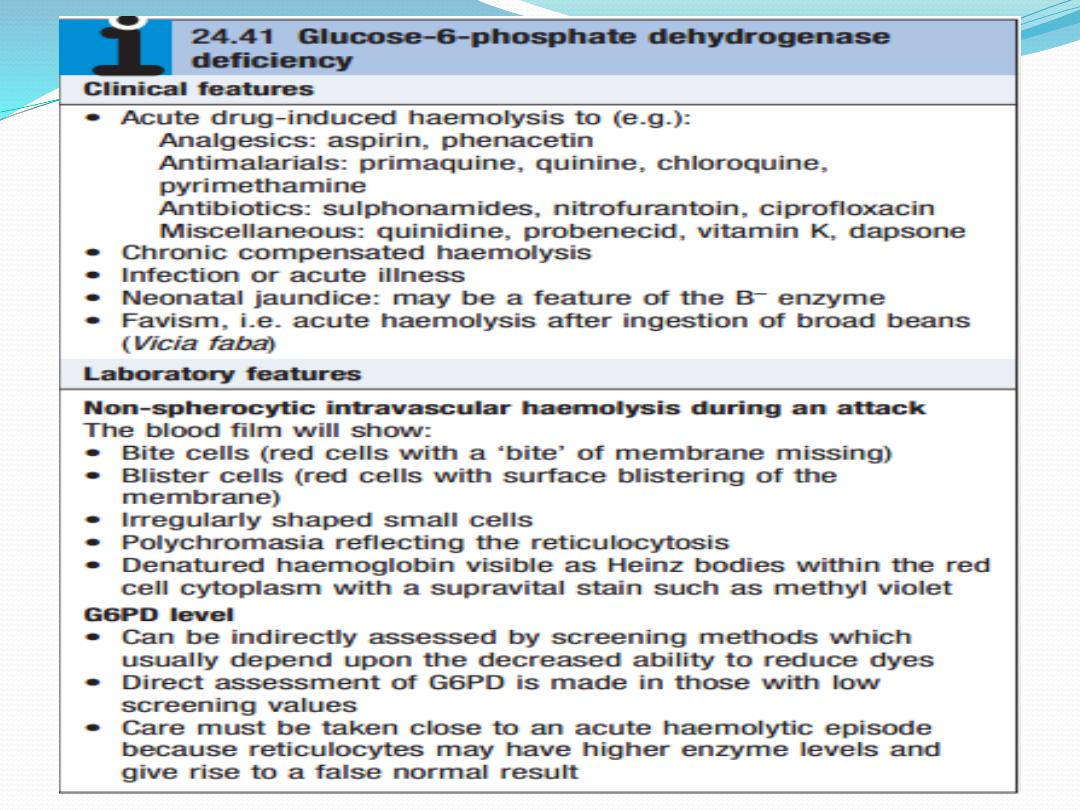

Glucose-6-phosphate

dehydrogenase deficiency

The enzyme glucose6phosphate dehydrogenase

(G6PD) is pivotal in the hexose monophosphate shunt

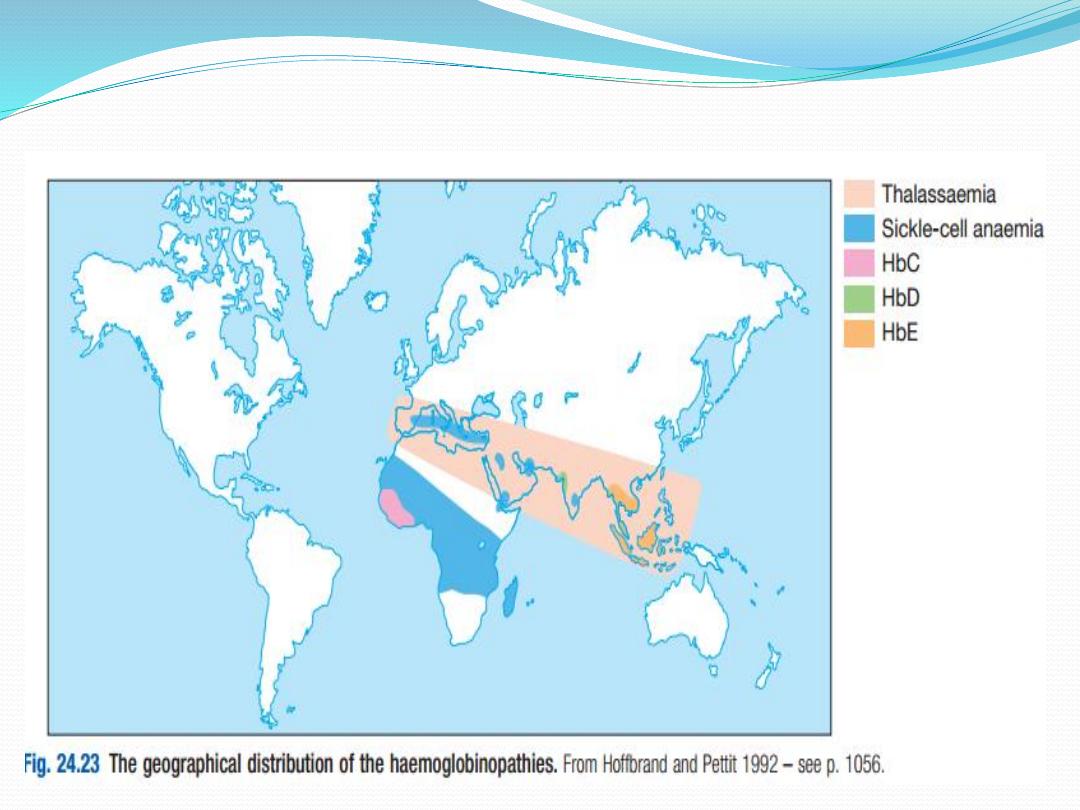

pathway. Deficiencies result in the most common

human enzymopathy, affecting

10%

of the world’s

population, with a geographical distribution which par

allels the malaria belt because

heterozygotes are pro

tected from malarial parasitisation

. The enzyme is a

heteromeric structure made of catalytic subunits

which are encoded by a gene on the

X chromosome

.

The deficiency therefore

affects males and rare

homozygous females

, but it is

carried by females

.

Carrier heterozygous females are usually only affected

in the neonatal period or in the presence of extreme

lyonisation, producing selective inactivation of the

nonaffected X chromosome.

Over 400 subtypes of G6PD are described. The most

common types associated with normal activity are the

B+ enzyme present in most Caucasians and 70% of

AfroCaribbeans, and the A+ variant present in 20% of

AfroCaribbeans. The two common variants associated

with reduced activity are the A− variety in

approximately 10% of AfroCaribbeans, and the

Mediterranean or B−Variety in Caucasians. In East and

West Africa, up to 20% of males and 4% of females

(homozygotes) are affected and have enzyme levels of

about 15% of normal. The deficiency in Caucasian and

Oriental populations is more severe, with enzyme

levels as low as 1%.

Management aims to stop any precipitant drugs and

treat any underlying infection. Acute transfusion

support may be lifesaving.

Pyruvate kinase deficiency

This is the second most common red cell enzyme

defect. It results in deficiency of ATP production and a

chronic haemolytic anaemia

. It is inherited as an

autosomal recessive trait

. The extent of anaemia is

variable; the blood film shows characteristic ‘

prickle

cells’

which resemble holly leaves. Enzyme activity is

only 5–20% of normal. Transfusion support may be

necessary.

Pyrimidine 5′nucleotidase

deficiency

The pyrimidine 5′nucleotidase enzyme catalyses the

dephosphorylation of nucleoside monophosphates and

is important during the degradation of RNA in reticulo

cytes. It is inherited as

an autosomal recessive trait

and

is as common as pyruvate kinase deficiency in Mediter

ranean, African and Jewish populations. The accumula

tion of excess ribonucleoprotein results in

coarse

basophilic stippling

, associated with a

chronic haemolytic

state.

The enzyme is very sensitive to inhibition by lead and

this is the reason why basophilic stippling is a feature of

lead poisoning.

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

This results from increased red cell destruction due to

red cell autoantibodies. The antibodies may be IgG or

M, or more rarely IgE or A.

If an antibody avidly fixes

complement, it will cause intravascular haemolysis,

but if complement activation is weak, the haemolysis

will be extravascular.

Antibody coated red cells lose

membrane to macrophages in the spleen and hence

spherocytes are present in the blood.

The optimum temperature at which the antibody is

active (thermal specificity) is used to classify immune

haemolysis:

•1) Warm antibodiesbind best at

37°C

and account for

80% of cases

. The majority are

IgG

and often react

against Rhesus antigens.

• 2) Cold antibodies bind best at

4°C

but can bind up

to 37°C in some cases. They are usually

IgM

and bind

complement. To be clinically relevant, they must act

within the range of normal body temperatures.

They account for the other

20% of cases

.

Warm autoimmune haemolysis

The incidence of warm autoimmune haemolysis is

approximately

1/100 000

population per annum; it

occurs at all ages but is more common in

middle age

and in

females.

No underlying cause is identified in up

to 50% of cases. The remainder are secondary to a wide

variety of other conditions.

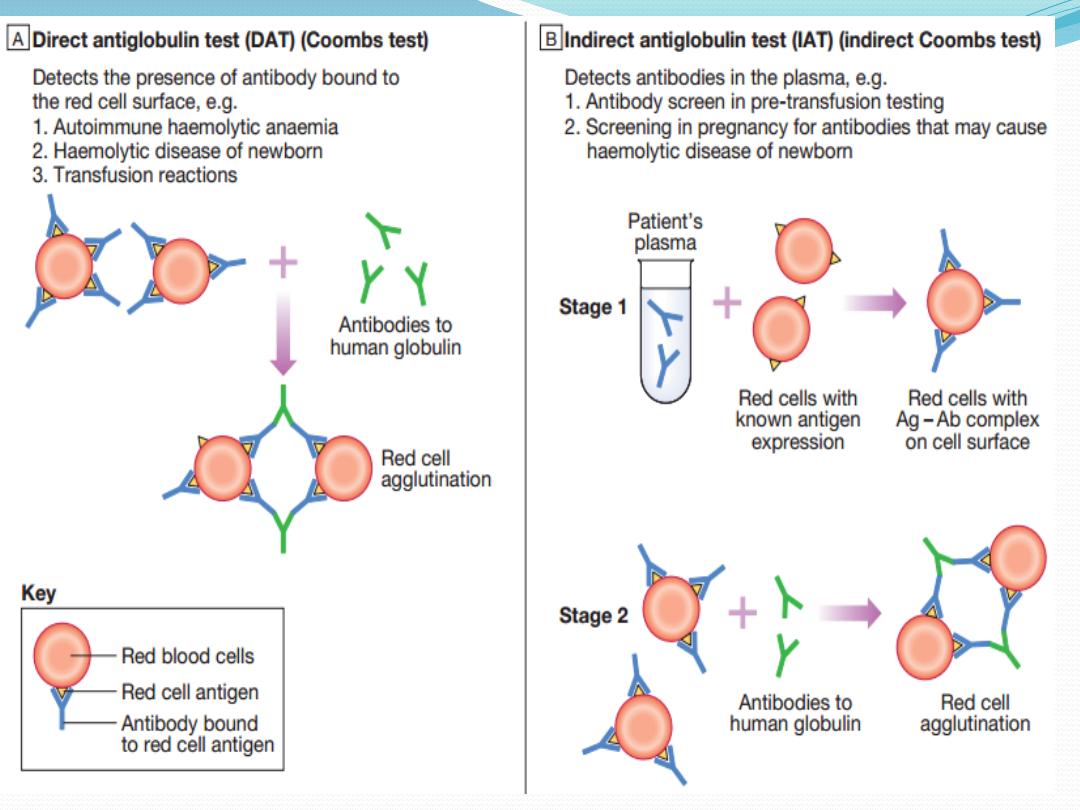

Investigations

There is evidence of haemolysis and spherocytes on

the blood film. The diagnosis is confirmed by the

direct Coombs or antiglobulin test.

The patient’s red cells are mixed with Coombs reagent,

which contains antibodies against human

IgG/M/complement. If the red cells have been coated by

antibody in vivo, the Coombs reagent will induce their

agglutination and this can be detected visually. The

relevant antibody can be eluted from the red cell surface

and tested against a panel of typed red cells to determine

against which red cell antigen it is directed. The most

common specificity is Rhesus and most often antie; this is

helpful when choosing blood to crossmatch. The direct

Coombs test can be negative in the presence of brisk

haemolysis. A positive test requires about 200 antibody

molecules to attach to each red cell; with a very avid

complementfixing antibody, haemolysis may occur at lower

levels of antibodybinding. The standard Coombs reagent

will miss IgA or IgE antibodies. Around 10% of all warm

autoimmune haemolytic anaemias are Coombs test-

negative.

Management

If the haemolysis is secondary to an underlying cause,

this must be treated and any implicated drugs stopped.

It is usual to treat patients initially with

prednisolone

1 mg/kg orally. A response is seen in 70–80% of cases

but may take up to 3 weeks; a rise in haemoglobin will

be matched by a fall in bilirubin, LDH and reticulocyte

levels. Once the haemoglobin has normalised and the

reticulocytosis resolved, the corticosteroid dose can be

reduced slowly over about 10 weeks. Corticosteroids

work by decreasing macrophage destruction of antibody-

coated red cells and reducing antibody production.

Transfusion support may be required for life

threatening problems, such as the development of

heart failure or rapid unabated falls in haemoglobin.

The least incompatible blood should be used but this

may still give rise to transfusion reactions or the

development of alloantibodies.

If the haemolysis fails to respond to corticosteroids or

can only be stabilised by large doses, then

splenectomy

should be considered

. This removes a main site of red

cell destruction and antibody production, with a good

response in 50–60% of cases. The operation can be

performed laparoscopically with reduced morbidity. If

splenectomy is not appropriate, alternative

immunosuppressive therapy with

azathioprine or

cyclophosphamide may be considered

. This is least

suitable for young patients, in whom longterm

immunosuppression carries a risk of secondary

neoplasms. The antiCD20 (B cell) monoclonal

antibody,

rituximab

, has shown some success in

difficult cases.

Cold agglutinin disease

This is due to antibodies, usually IgM, which bind to

the red cells at low temperatures and cause them to

agglutinate. It may cause intravascular haemolysis if

complement fixation occurs. This can be chronic when

the antibody is monoclonal, or acute or transient when

the antibody is polyclonal.

Chronic cold agglutinin disease

This affects elderly patients and may be associated

with an underlying

lowgrade B cell lymphoma

. It

causes a lowgrade intravascular haemolysis with cold,

painful and often blue fingers, toes, ears or nose (so-

called

acrocyanosis

). The latter is due to red cell

agglutination in the small vessels in these colder

exposed areas. The blood film shows red cell

agglutination and the MCV may be spuriously high

because the automated analysers detect aggregates as

single cells.

Monoclonal IgM usually has antiI or, less often, antii

specificity. Treatment is directed at any underlying

lymphoma but if the disease is idiopathic, then

patients must keep extremities warm, especially in

winter. Some patients respond to corticosteroid

therapy and blood transfusion may be considered, but

the crossmatch sample must be placed in a transport

flask at a temperature of 37°C and blood administered

via a bloodwarmer. All patients should receive folic

acid supplementation.

Other causes of cold agglutination

Cold agglutination can occur in association with

Mycoplasma pneumoniae or with infectious

mononucleosis.

Paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria is a very rare cause

seen in children, in association with

viral or bacterial

infection.

An IgG antibody binds to red cells in the

peripheral circulation but lysis occurs in the central

circulation when complement fixation takes place.

This antibody is termed the Donath–Landsteiner

antibody and has specificity against the P antigen on

the red cells.

Alloimmune haemolytic anaemia

Alloimmune haemolytic anaemia is caused by

antibodies against nonself red cells

, and occurs after

unmatched transfusion , or after maternal

sensitisation to paternal antigens on fetal cells.

Non-immune haemolytic anaemia

Physical trauma:

Physical disruption of red cells may occur in a number

of conditions and is characterised by the presence of

red cell fragments on the blood film and markers of

intravascular haemolysis:

•1) Mechanical heart valves.High flow through

incompetent valves or periprosthetic leaks through

the suture ring holding a valve in place result in

shear stress damage.

2)March haemoglobinuria. Vigorous exercise, such as

prolonged marching or marathon running, can

cause red cell damage in the capillaries in the feet.

•3) Thermal injury. Severe burns cause thermal

damage to red cells, characterised by fragmentation

and the presence of microspherocytes in the blood.

•4) Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. Fibrin

deposition in capillaries can cause severe red cell

disruption. It may occur in a wide variety of

conditions: disseminated carcinomatosis, malignant or

pregnancyinduced hypertension, haemolytic

uraemic syndrome , thrombotic thrombocytopenic

purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation

Infection:

Plasmodium falciparum malaria may be associated

with intravascular haemolysis; when severe, this is

termed blackwater fever because of the associated

haemoglobinuria. Clostridium perfringens

septicaemia , usually in the context of ascending

cholangitis, may cause severe intravascular haemolysis

with marked spherocytosis due to bacterial production

of a lecithinase which destroys the red cell membrane.

Chemicals or drugs:

Dapsone and sulfasalazine cause haemolysis by oxida

tive denaturation of haemoglobin. Denatured haemo

globin forms Heinz bodies in the red cells, visible on

supravital staining with brilliant cresyl blue. Arsenic

gas, copper, chlorates, nitrites and nitrobenzene

derivatives may all cause haemolysis.

Paroxysmal nocturnal

haemoglobinuria

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) is a

rare acquired,

nonmalignant clonal expansion of

haematopoietic stem cells deficient in GPIanchor

protein

; it results in intravascular haemolysis and

anaemia because of increased sensitivity of red cells to

lysis by complement. Episodes of intravascular

haemolysis result in haemoglobinuria, most noticeable

in early morning urine, which has a characteristic red–

brown colour.

The disease is associated with an

increased risk of

venous thrombosis in unusual sites, such as the liver or

abdomen

. PNH is also associated

with hypoplastic

bone marrow failure, aplastic anaemia and

myelodysplastic syndrome

. Management is supportive

with transfusion and treatment of thrombosis.

Recently, the anticomplement C5 monoclonal

antibody

eculizumab

was shown to be effective in

reducing haemolysis

Haemoglobinopathies

These diseases are caused by mutations affecting the

genes encoding the globin chains of the haemoglobin

molecule. Normal haemoglobin is comprised of two

alpha and two nonalpha globin chains. Alpha globin

chains are produced throughout life, including in the

fetus, so severe mutations may cause intrauterine

death.

Production of nonalpha chains varies with age; fetal

haemoglobin (HbFαα/γγ) has two gamma chains,

while the predominant adult haemoglobin (HbA-

αα/ββ) has two beta chains. Thus, disorders affecting

the beta chains do not present until after 6 months of

age. A constant small amount of haemoglobin

A2(HbA2αα/δδ, usually less than 2%) is made from

birth.

Qualitative abnormalities –

abnormal haemoglobins

In qualitative abnormalities (called the abnormal

haemoglobins), there is a functionally important

alteration in the amino acid structure of the

polypeptide chains of the globin chains. Several

hundred such variants are known; they were originally

designated by letters of the alphabet, e.g. S, C, D or E,

but are now described by names usually taken from

the town or district in which they were first described.

The bestknown example is haemoglobin S, found in

sicklecell anaemia. Mutations around the haem-

binding pocket cause the haem ring to fall out of the

structure and produce an unstable

haemoglobin. These substitutions often change the

charge of the globin chains, producing different

electrophoretic mobility, and this forms the basis for

the diagnostic use of haemoglobin electrophoresis to

identify haemoglobinopathies.

Quantitative abnormalities –

thalassaemias

In quantitative abnormalities (the thalassaemias),

there are mutations causing a reduced rate of

production of one or other of the globin chains,

altering the ratio of alpha to nonalpha chains. In

alphathalassaemia excess beta chains are present,

whilst in betathalassaemia excess alpha chains are

present. The excess chains precipitate, causing red cell

membrane damage and reduced red cell survival.

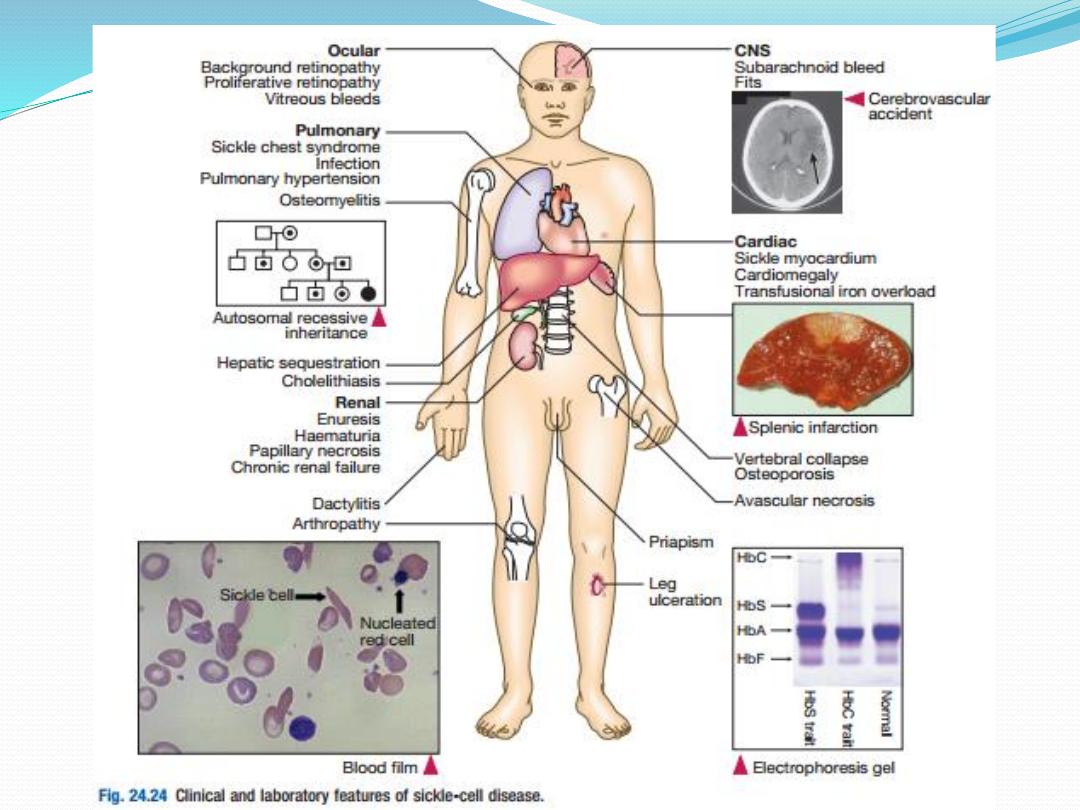

Sickle-cell anaemia

Sicklecell disease results from a

single glutamic acid to

valine substitution at position 6 of the beta globin

polypeptide chain.

It is inherited as an autosomal recessive

trait . Homozygotes only produce abnormal

beta chains that make haemoglobin S (HbS, termed SS),

and this results in the clinical syndrome of sicklecell

disease. Heterozygotes produce a mixture of normal and

abnormal beta chains that make normal HbA and HbS

(termed AS), and this results in the clinically asymptomatic

sicklecell trait.

Epidemiology

The heterozygote frequency is over 20% in tropical

Africa. In black American populations, sicklecell trait

has a frequency of 8%.

Individuals with sicklecell trait

are relatively resistant to the lethal effects of

falciparum malaria in early childhood

; the high

prevalence in equatorial Africa can be explained by the

survival advantage it confers in areas where falciparum

malaria is endemic.

However, homozygous patients

with sicklecell anaemia do not have correspondingly

greater resistance to falciparum malaria.

Pathogenesis

When haemoglobin S is deoxygenated, the molecules

of haemoglobin polymerise to form pseudocrystalline

structures known as ‘

tactoids’

. These distort the red

cell membrane and produce characteristic sickle-

shaped cells . The polymerisation is reversible when

reoxygenation occurs. The distortion of the red cell

membrane, however, may become permanent and the

red cell ‘irreversibly sickled’.

The greater the concentration of sicklecell

haemoglobin in the individual cell, the more easily

tactoids are formed, but this process may be enhanced

or retarded by the presence of other haemoglobins.

Thus, the abnormal haemoglobin C variant

participates in the polymerisation more readily than

haemoglobin A, whereas haemoglobin F strongly

inhibits polymerisation.

Clinical features

Sickling is precipitated by 1)

hypoxia,2) acidosis,

3)dehydration and 4)infection.

Irreversibly sickled

cells have a shortened survival and plug vessels in the

microcirculation. This results in a number of acute

syndromes, termed ‘crises’, and chronic organ damage:

1)Painful vaso-occlusive crisis. Plugging of small

vessels in the bone produces acute severe bone

pain. This affects areas of active marrow: the hands

and feet in children (socalled dactylitis) or the femora,

humeri, ribs, pelvis and vertebrae in adults.

Patients usually have a systemic response with

tachycardia, sweating and a fever. This is the most

common crisis

2)Sickle chest syndrome. This may follow a vaso

occlusive crisis and is the most common cause of

death in adult sickle disease. Bone marrow

infarction results in fat emboli to the lungs, which

cause further sickling and infarction, leading to

ventilatory failure if not treated.

3)Sequestration crisis. Thrombosis of the venous

outflow from an organ causes loss of function and

acute painful enlargement. In children, the spleen is

the most common site. Massive splenic enlargement

may result in severe anaemia, circulatory collapse and

death. Recurrent sickling in the spleen in childhood

results in infarction and adults may have no functional

spleen. In adults, the liver may undergo sequestration

with severe pain due to capsular stretching. Priapism is

a complication seen in affected men.

4)Aplastic crisis. Infection with human parvovirus

B19 results in a severe but selflimiting red cell aplasia.

This produces a very low haemoglobin, which may

cause heart failure. Unlike in all other sickle crises, the

reticulocyte count is low.

Investigations

Patients with sicklecell disease have a compensated

anaemia, usually around 60–80 g/L. The blood film

shows sickle cells, target cells and features of

hyposplenism. A reticulocytosis is present. The

presence of HbS can be demonstrated by exposing red

cells to a reducing agent such as sodium dithionite;

HbA gives a clear solution, whereas HbS polymerises

to produce a turbid solution.

This forms the basis of emergency screening tests

before surgery in appropriate ethnic groups but cannot

distinguish between sicklecell trait and disease. The

definitive diagnosis requires haemoglobin

electrophoresis to demonstrate the absence of HbA, 2–

20% HbF and the predominance of HbS. Both parents

of the affected individual will have sicklecell trait.

Management

All patients with sicklecell disease should receive

prophylaxis with daily folic acid, and penicillin V to

protect against pneumococcal infection, which may be

lethal in the presence of hyposplenism. These patients

should be vaccinated against pneumococcus,

meningococcus, Haemophilus influenzaeB, hepatitis B

and seasonal influenza.

Vasoocclusive crises are managed by aggressive

rehydration, oxygen therapy, adequate analgesia

(which often requires opiates) and antibiotics.

Transfusion should be with fully genotyped blood

wherever possible. Simple top up transfusion may be

used in a sequestration or aplastic crisis.

A regular transfusion programme to suppress HbS

production and maintain the HbS level below 30%

may be indicated in patients with recurrent severe

complications, such as cerebrovascular accidents in

children or chest syndromes in adults. Exchange

transfusion, in which a patient is simultaneously

venesected and transfused to replace HbS with HbA,

may be used in lifethreatening crises or to prepare

patients for surgery.

A high HbF level inhibits polymerisation of HbS and

reduces sickling. Patients with sicklecell disease and

high HbF levels have a mild clinical course with few

crises. Some agents are able to increase synthesis of

HbF and this has been used to reduce the frequency of

severe crises. The oral cytotoxic agent

hydroxycarbamide has been shown to have clinical

benefit with acceptable side effects in children and

adults who have recurrent severe crises.

Relatively few allogeneic stem cell transplants from

HLAmatched siblings have been performed but this

procedure appears to be potentially curative.

Prognosis

In Africa, few children with sicklecell anaemia survive

to adult life without medical attention. Even with

standard medical care, approximately 15% die by the

age of 20 years and 50% by the age of 40 years.

Other abnormal haemoglobins

Another beta chain haemoglobinopathy, haemoglobin

C (HbC) disease, is clinically silent but associated

with

microcytosis and target cells on the blood film.

Compound heterozygotes inheriting one HbS gene

and one HbC gene from their parents have

haemoglobin SC disease, which behaves like a mild

form of sicklecell disease. SC disease is associated with

a reduced frequency of crises but is not uncommonly

linked with complications in pregnancy and

retinopathy.

The thalassaemias

Thalassaemia is an inherited impairment of

haemoglobin production, in which there is partial or

complete failure to synthesise a specific type of globin

chain. In alphathalassaemia, disruption of one or both

alleles on chromosome 16 may occur, with production

of some or no alpha globin chains. In beta-

thalassaemia, defective production usually results

from disabling point mutations causing no (β0) or

reduced (β–) beta chain production.

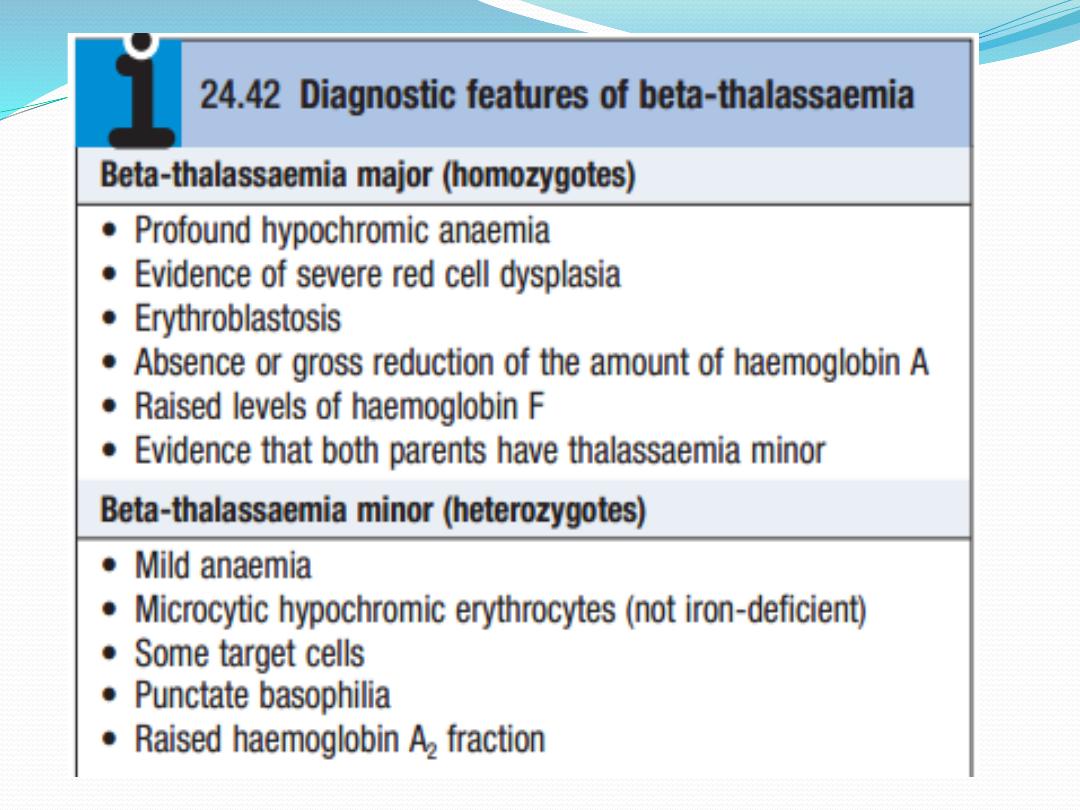

Beta-thalassaemia

Failure to synthesise beta chains (betathalassaemia) is

the most common type of thalassaemia, most prevalent

in the Mediterranean area. Heterozygotes have thalas

saemia minor, a condition in which there is usually mild

anaemia and little or no clinical disability, which may be

detected only when iron therapy for a mild microcytic

anaemia fails. Homozygotes (thalassaemia major)

either

are unable to synthesise haemoglobin A or, at best,

produce very little; after the first 4–6 months of life,

they

develop profound hypochromic anaemia. Intermediate

grades of severity occur.

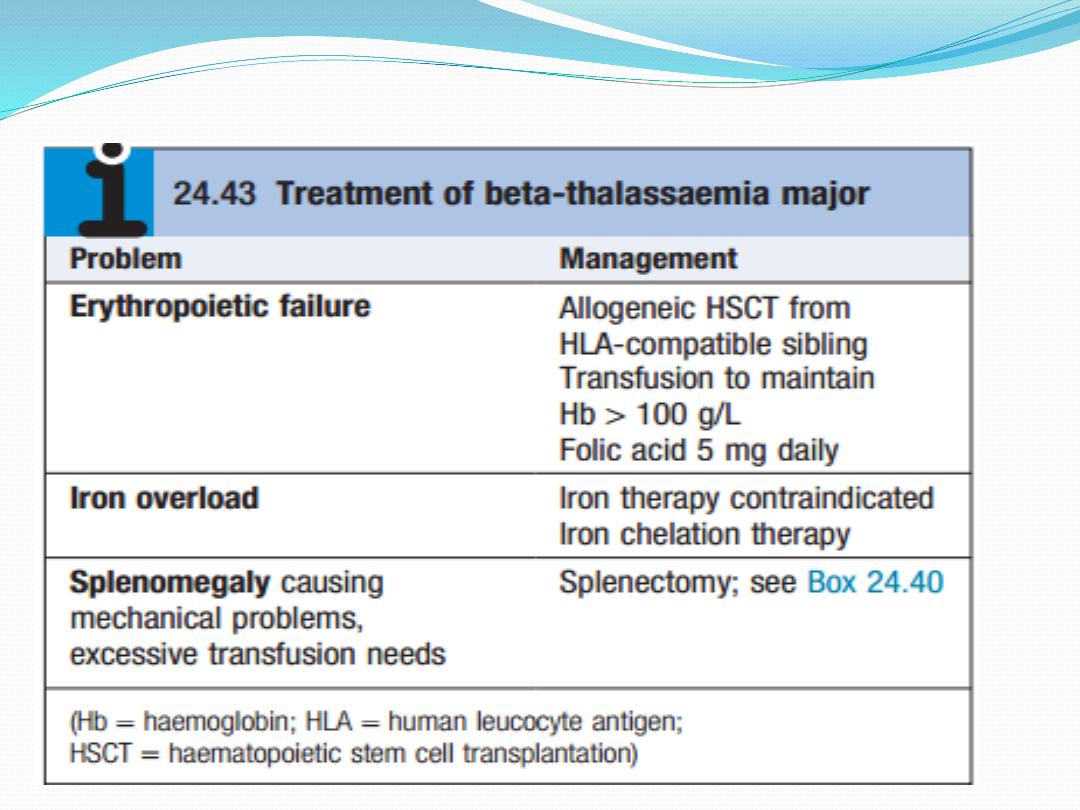

Management and prevention

Cure is now a possibility for selected children, with

allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation .It

is possible to identify a fetus with homozygous beta-

thalassaemia by obtaining chorionic villous material

for DNA analysis sufficiently early in pregnancy to

allow termination. This examination is only

appropriate if both parents are known to be carriers

(betathalassaemia minor) and will accept a

termination.

Alpha-thalassaemia

Reduced or absent alpha chain synthesis is common

in

Southeast Asia. There are two alpha gene loci on chro

mosome 16 and therefore each individual carries four

alpha gene alleles.

• If one is deleted, there is no clinical effect.

• If two are deleted, there may be a mild

hypochromic anaemia.

• If three are deleted, the patient has haemoglobin H

disease.

• If all four are deleted, the baby is stillborn (hydrops

fetalis).

Haemoglobin H is a betachain tetramer, formed from

the excess of beta chains, which is functionally useless,

so that patients rely on their low levels of HbA for

oxygen transport. Treatment of haemoglobin H

disease is similar to that of betathalassaemia of

intermediate severity, involving folic acid

supplementation, transfusion if required and

avoidance of iron therapy.

THANK YOU

FOR LISTENING