Dr. Mohamed Ghalib

Internal Medicine

TUCOM

5

th

year

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is by far the most common form of arthritis

and is a major cause of pain and disability in older people.

It is characterised by focal loss of articular cartilage, subchondral

osteosclerosis, osteophyte formation at the joint margin, and

remodelling of joint contour with enlargement of affected joints.

Epidemiology

The prevalence rises progressively with age and it

has been estimated that 45% of all people develop

knee OA and 25% hip OA at some point during life.

Although some are asymptomatic, the lifetime risk

of having a total hip or knee replacement for OA in

someone aged 50 is about 11% for women and 8%

for men in the UK. There are major ethnic

differences in susceptibility: the prevalence of hip

OA is lower in Africa, China, Japan and the Indian

subcontinent than in European countries, and that of

knee OA is higher.

Pathophysiology

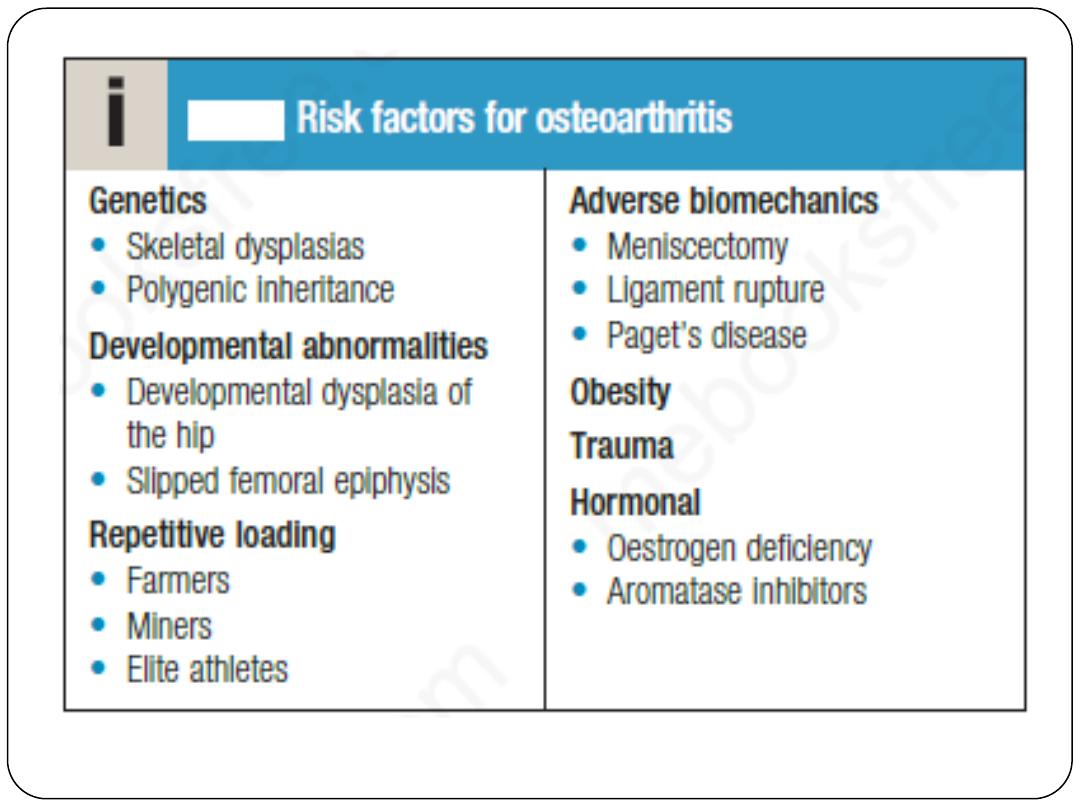

OA is a complex disorder with both genetic and environmental

components.

Genetic factors are recognised as playing a key role in the pathogenesis

of OA. Family-based studies have estimated that the heritability of OA

ranges from about 43% at the knee to between 60% and 65% at the hip

and hand, respectively. In most cases, the inheritance is polygenic and

mediated by several genetic variants of small effect.

OA can, however, be a component of multiple epiphyseal dysplasias,

which are caused by mutations in the genes that encode components of

cartilage matrix.

Structural abnormalities, such as slipped femoral epiphysis and

developmental dysplasia of the hip, are also associated with a high risk

of OA, presumably due to abnormal load distribution across the joint.

Biomechanical factors play an important role in OA related to certain

occupations, such as farmers (hip OA), miners (knee OA) and elite or

professional athletes (knee and ankle OA). It has been speculated that the

higher prevalence of knee OA in the Indian subcontinent and East Asia

might be accounted for by squatting.

There is also a high risk of OA in people who have had destabilising

injuries, such as cruciate ligament rupture, and those who have had

meniscetomy.

For most individuals, however, participation in recreational sport does not

appear to increase the risk significantly.

There is a strong association between obesity and OA, particularly of the

hip. This is thought to be due partly to biomechanical factors but it has also

been speculated that cytokines released from adipose tissue may play a

role.

Oestrogen appears to play a role; lower rates of OA have been observed

in women who use hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and women

who receive aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer often

experience a flare in symptoms of OA.

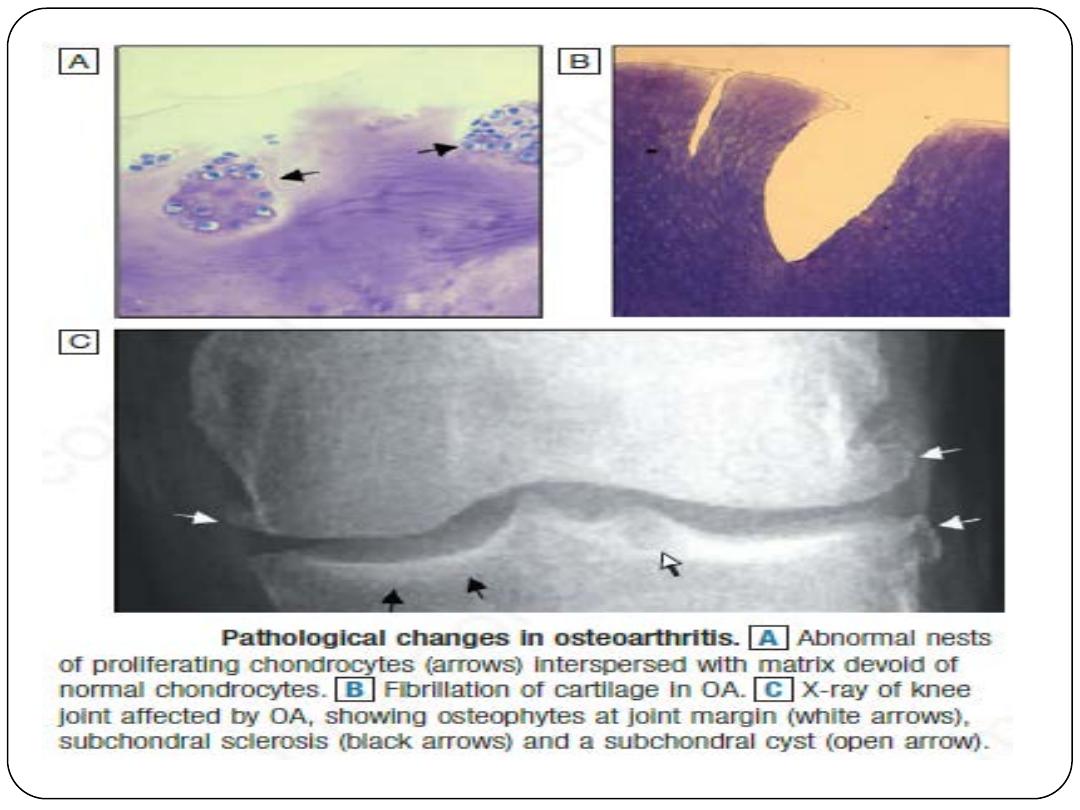

Degeneration of articular cartilage is the defining feature of OA.

Under normal circumstances, chondrocytes are terminally

differentiated cells but in OA they start dividing to produce nests

of metabolically active cells.

Initially, matrix components are produced by these cells at an

increased rate, but at the same time there is accelerated

degradation of the major structural components of cartilage

matrix, including aggrecan and type II collagen. Eventually, the

concentration of aggrecan in cartilage matrix falls and makes the

cartilage vulnerable to load-bearing injury. Fissuring of the

cartilage surface (‘fibrillation’) then occurs, leading to the

development of deep vertical clefts, localised chondrocyte death

and decreased cartilage thickness. This is initially focal, mainly

targeting the maximum load-bearing part of the joint, but

eventually large parts of the cartilage surface are damaged.

Calcium pyrophosphate and basic calcium phosphate crystals

often become deposited in the abnormal cartilage.

OA is also accompanied by abnormalities in subchondral bone,

which becomes sclerotic and the site of subchondral cysts.

Fibrocartilage is produced at the joint margin, which undergoes

endochondral ossification to form osteophytes. Bone remodelling

and cartilage thinning slowly alter the shape of the OA joint,

increasing its surface area. It is almost as though there is a

homeostatic mechanism operative in OA that causes enlargement

of the failing joint to spread the mechanical load over a greater

surface area. Patients with OA also have higher BMD values at

sites distant from the joint and this is particularly associated with

osteophyte formation. This is in keeping with observations made

in epidemiological studies that show that patients with OA are

partially protected from developing osteoporosis and vice versa.

This is likely to be due to the fact that the genetic factors that

predispose to osteoporosis might be protective for OA.

The synovium in OA is often hyperplastic and may be the site of

inflammatory change, but to a much lesser extent than in RA and

other inflammatory arthropathies. Osteochondral bodies

commonly occur within the synovium, reflecting chondroid

metaplasia or secondary uptake and growth of damaged cartilage

fragments. The outer capsule also thickens and contracts, usually

retaining the stability of the remodelling joint. The muscles

surrounding affected joints commonly show evidence of wasting

and non-specific type II fibre atrophy.

Clinical features

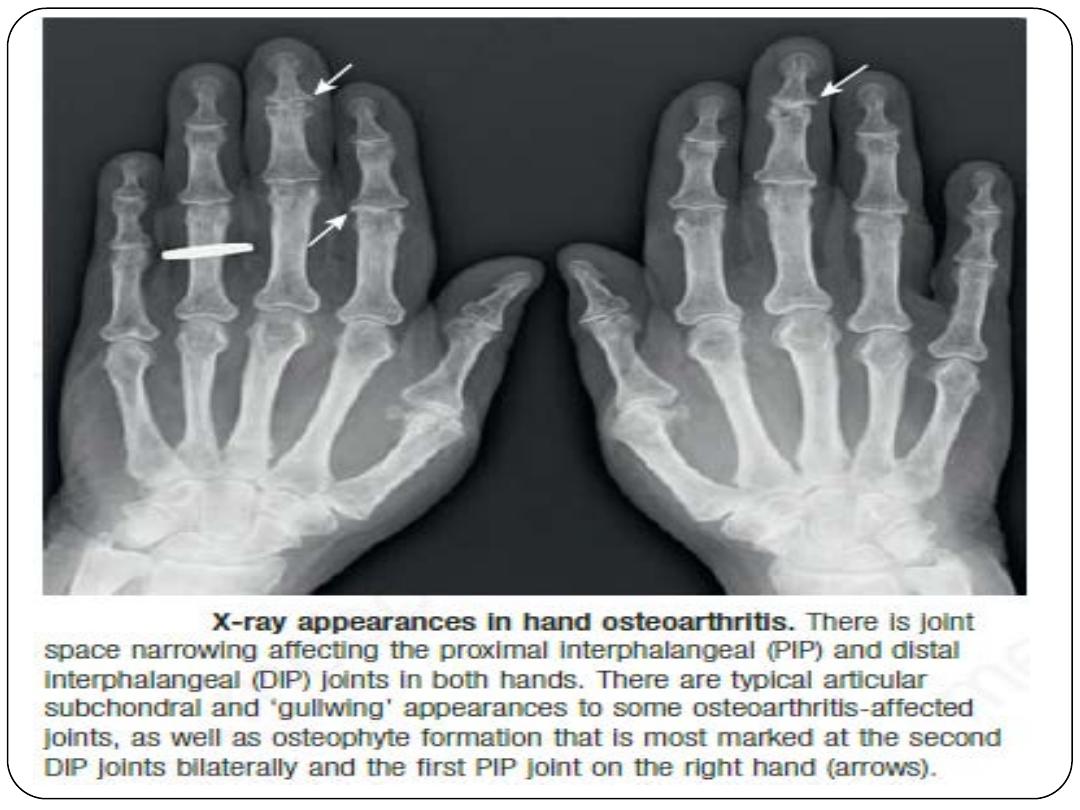

OA has a characteristic distribution, mainly targeting the hips, knees,

PIP and DIP joints of the hands, neck and lumbar spine.

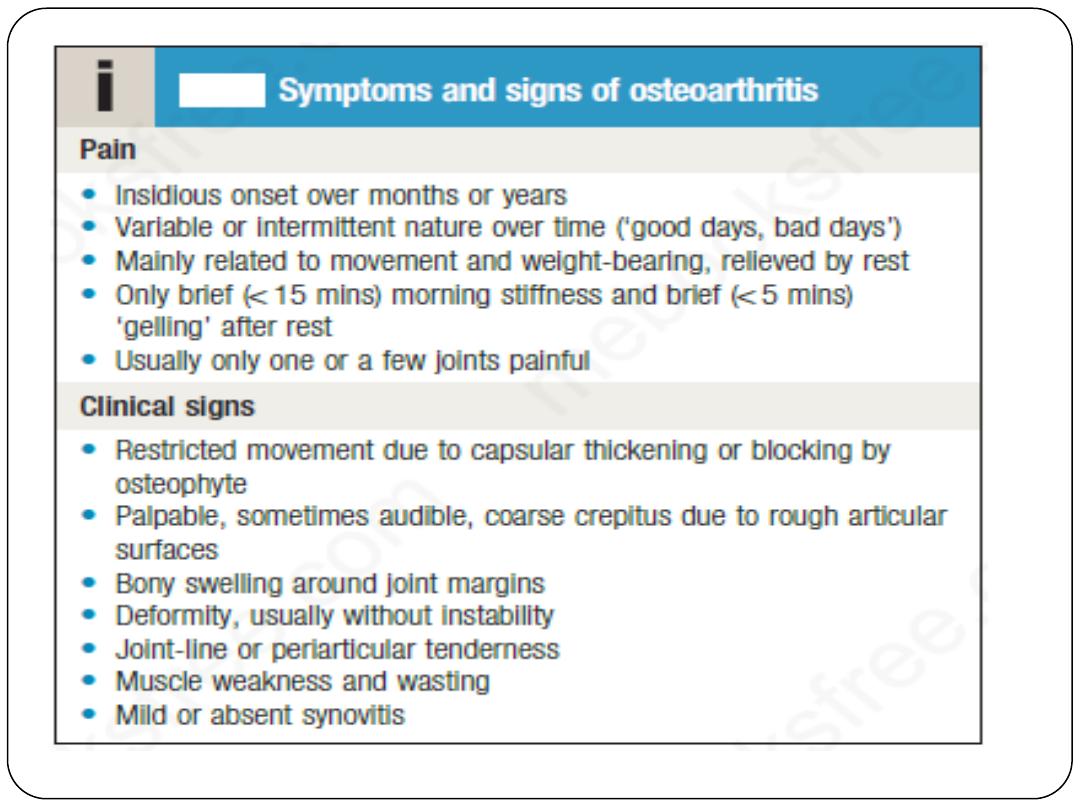

The main presenting symptoms are pain and functional restriction.

The causes of pain in OA are not completely understood but may

relate to increased pressure in subchondral bone (mainly causing night

pain), trabecular microfractures, capsular distension and low-grade

synovitis. Pain may also result from bursitis and enthesopathy

secondary to altered joint mechanics. Typical OA pain has the

characteristics listed in Box. For many people, functional restriction of

the hands, knees or hips is an equal, if not greater, problem than pain.

The clinical findings vary according to severity but are principally those

of joint damage.

The correlation between the presence of structural change, as

assessed by imaging, and symptoms such as pain and disability

varies markedly according to site. It is stronger at the hip than at

the knee, and poor at most small joints. This suggests that the risk

factors for pain and disability may differ from those for structural

change. At the knee, for example, reduced quadriceps muscle

strength and adverse psychosocial factors (anxiety, depression)

correlate more strongly with pain and disability than the degree

of radiographic change.

Radiological evidence of OA is very common in middle-aged and

older people, and the disease may coexist with other conditions,

so it is important to remember that pain in a patient with OA

may be due to another cause.

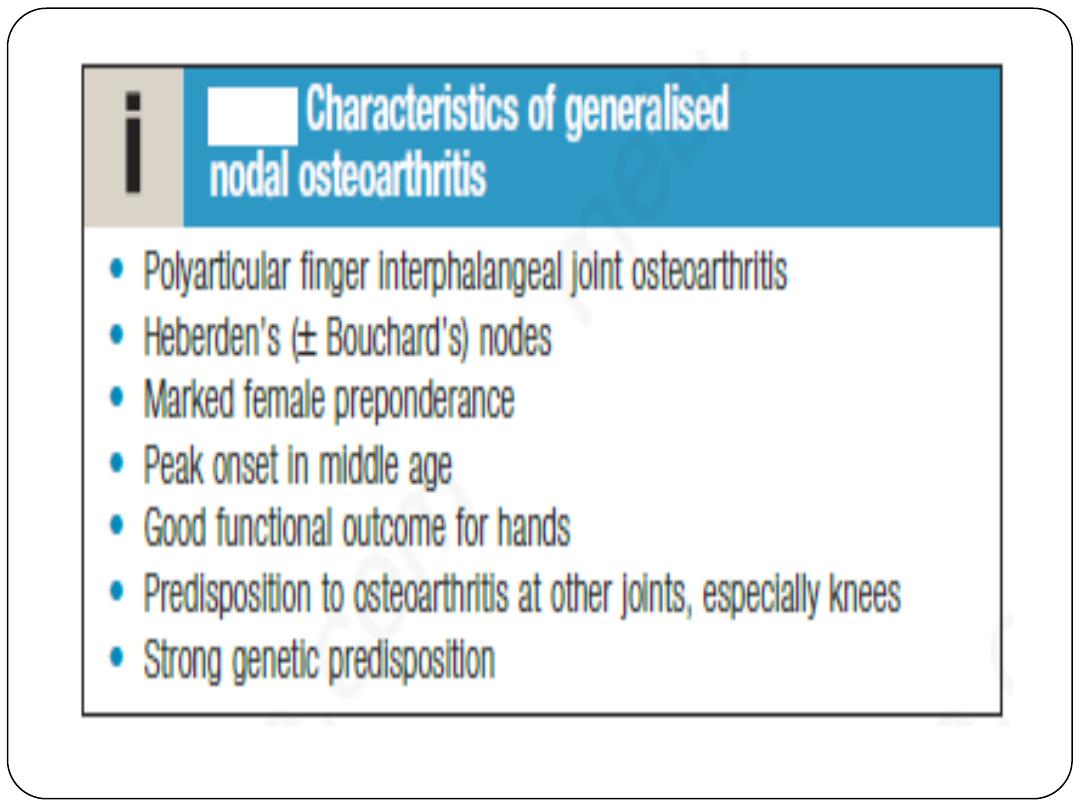

Generalised nodal OA

Some patients are asymptomatic whereas others develop pain, stiffness and

swelling of one or more PIP and DIP joints of the hands from the age of

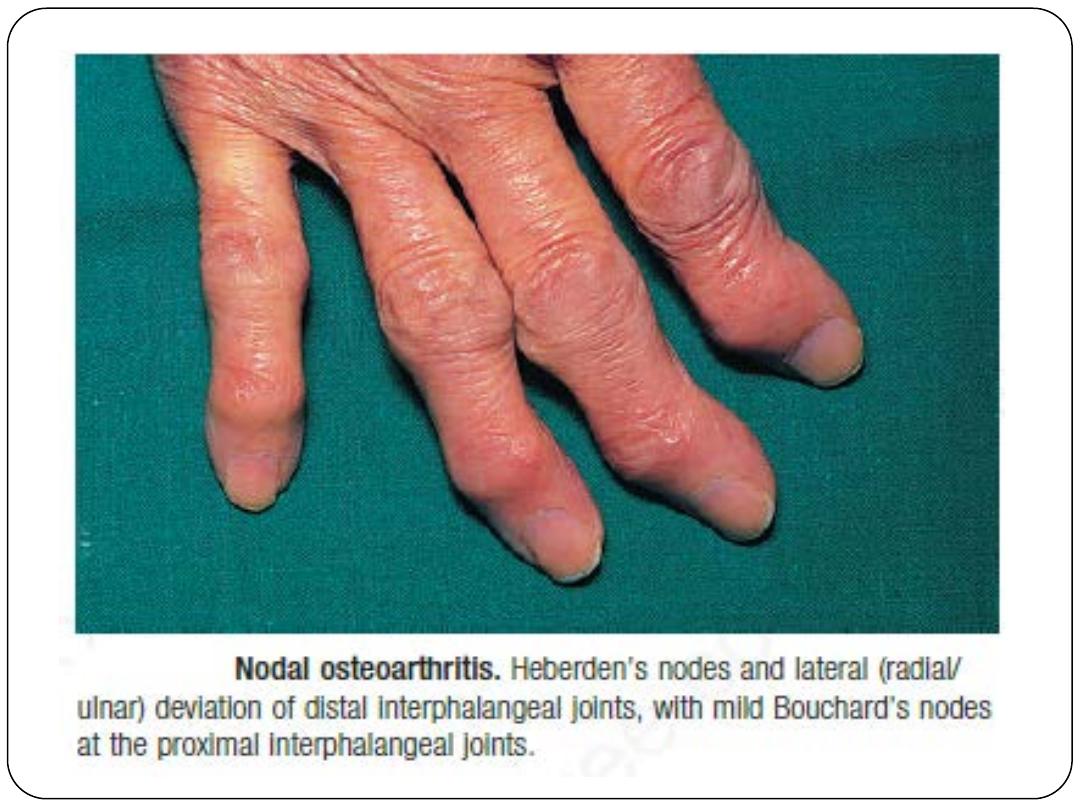

about 40 years onwards. Gradually, these develop posterolateral swellings on

each side of the extensor tendon, which slowly enlarge and harden to

become Heberden’s (DIP) and Bouchard’s (PIP) nodes.

Typically, each joint goes through a phase of episodic symptoms (1–5 years)

while the node evolves and OA develops. Once OA is fully established,

symptoms may subside and hand function often remains good. Affected joints

are enlarged as a result of osteophyte formation and often show

characteristic lateral deviation, reflecting the asymmetric focal cartilage loss

of OA. Involvement of the first CMC joint is also common, leading to pain

on trying to open bottles and jars, and functional impairment. Clinically, it

may be detected by the presence of crepitus on joint movement, and

squaring of the thumb base.

Generalised nodal OA has a very strong genetic component: the daughter of an

affected mother has a 1 in 3 chance of developing nodal OA herself. People

with nodal OA are also at increased risk of OA at other sites, especially the

knee.

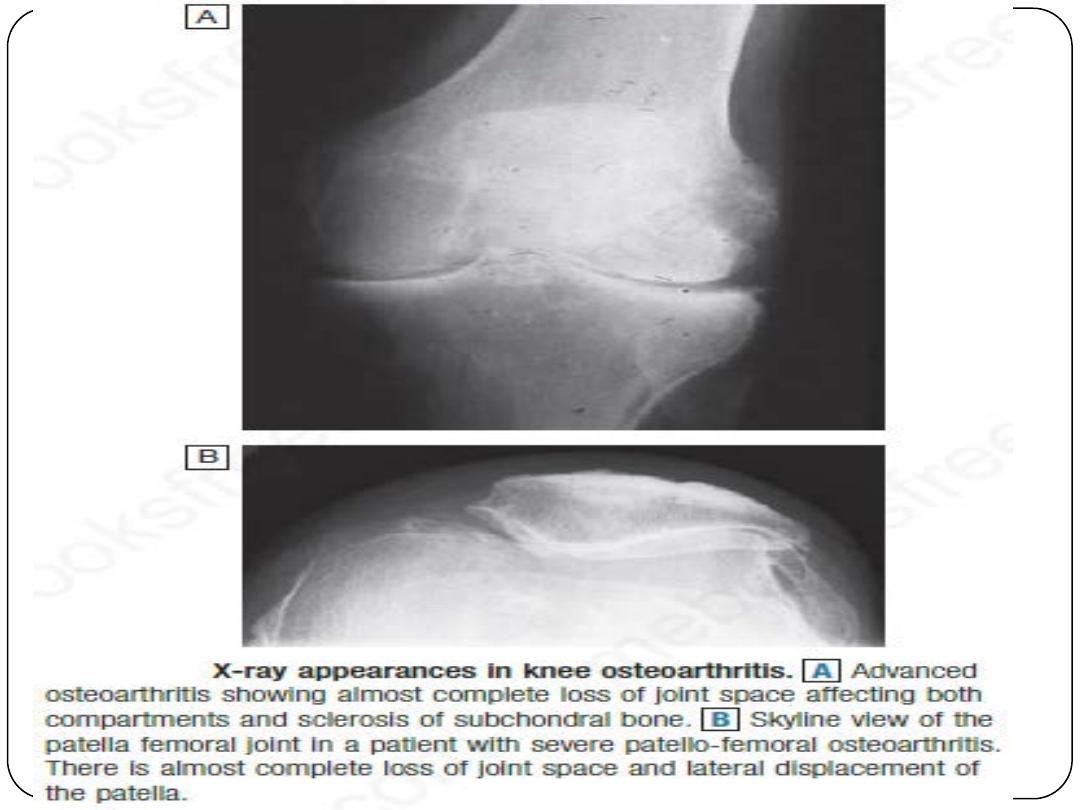

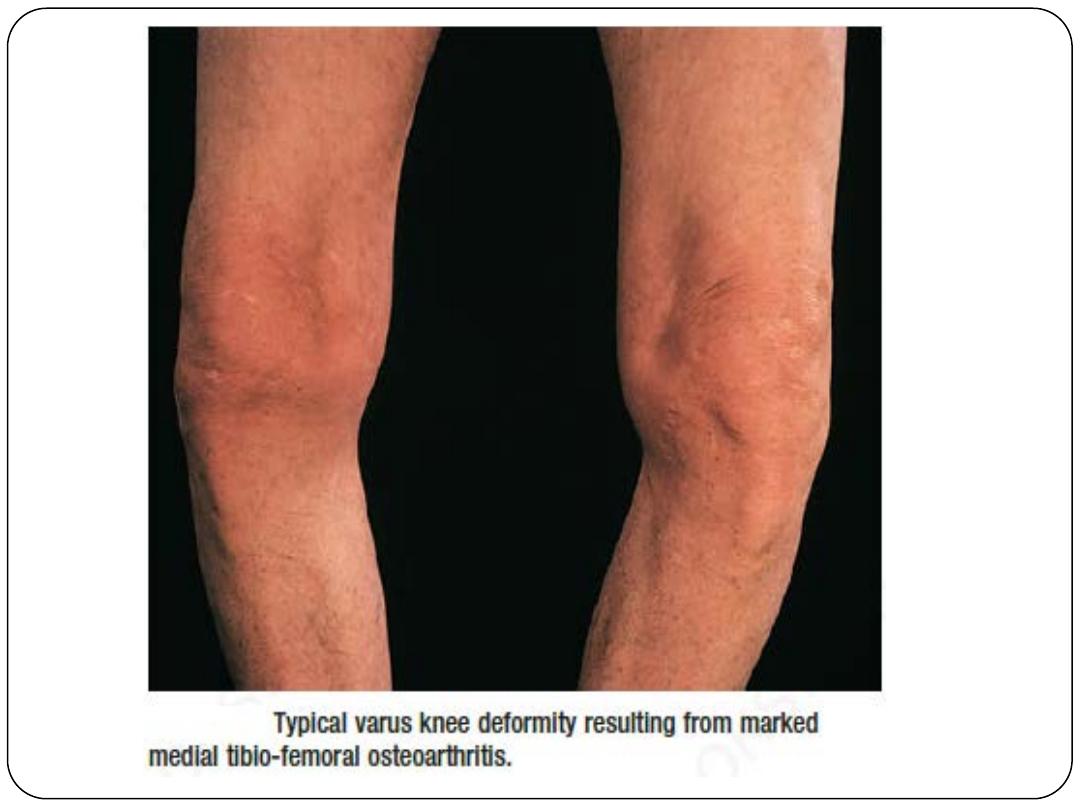

Knee OA

At the knee, OA principally targets the patello-femoral and

medial tibio-femoral compartments but eventually spreads to

affect the whole of the joint. It may be isolated or occur as part

of generalised nodal OA.

Most patients have bilateral and symmetrical involvement.

In men, trauma is often a more important risk factor and may

result in unilateral OA.

The pain is usually localised to the anterior or medial aspect of

the knee and upper tibia. Patello-femoral pain is usually worse

going up and down stairs or inclines. Posterior knee pain

suggests the presence of a complicating popliteal cyst (Baker’s

cyst). Prolonged walking, rising from a chair, getting in or out of

a car, or bending to put on shoes and socks may be difficult.

Local examination findings may include:

• a jerky, asymmetric (antalgic) gait with less time weightbearing on the

painful side

• a varus or, less commonly, valgus and/or a fixed flexion deformity

• joint-line and/or periarticular tenderness (secondary anserine bursitis

and medial ligament enthesopathy, causing tenderness of the upper

medial tibia)

.

restricted flexion and extension with coarse crepitus

• weakness and wasting of the quadriceps muscle

• bony swelling around the joint line.

CPPD crystal deposition in association with OA is common at the knee.

This may result in a more overt inflammatory component (stiffness,

effusions) and super-added acute attacks of synovitis (‘pseudogout’),

which may be associated with more rapid radiographic and clinical

progression.

Hip OA

Hip OA most commonly targets the superior aspect of the joint. It is

often unilateral at presentation, frequently progresses with superolateral

migration of the femoral head, and has a poor prognosis.

The less common central (medial) OA shows more central cartilage loss

and is largely confined to women. It is often bilateral at presentation and

can be associated with generalised nodal OA. It has a better prognosis

than superior hip OA and progression to axial migration of the femoral

head is uncommon.

The hip shows the best correlation between symptoms and radiographic

change. Hip pain is usually maximal deep in the anterior groin, with

variable radiation to the buttock, anterolateral thigh, knee or shin. Lateral

hip pain, worse on lying on that side with tenderness over the greater

trochanter, suggests secondary trochanteric bursitis. Common functional

difficulties are the same as for knee OA; in addition, restricted hip

abduction in women may cause pain during sexual intercourse.

Examination may reveal:

an antalgic gait

weakness and wasting of quadriceps and gluteal muscles

pain and restriction of internal rotation with the hip

flexed – the earliest and most sensitive sign of hip OA; other

movements may subsequently be restricted and painful

anterior groin tenderness just lateral to the femoral pulse

fixed flexion, external rotation deformity of the hip

ipsilateral leg shortening with severe joint attrition and superior

femoral migration.

Obesity is associated with more rapid progression of hip OA.

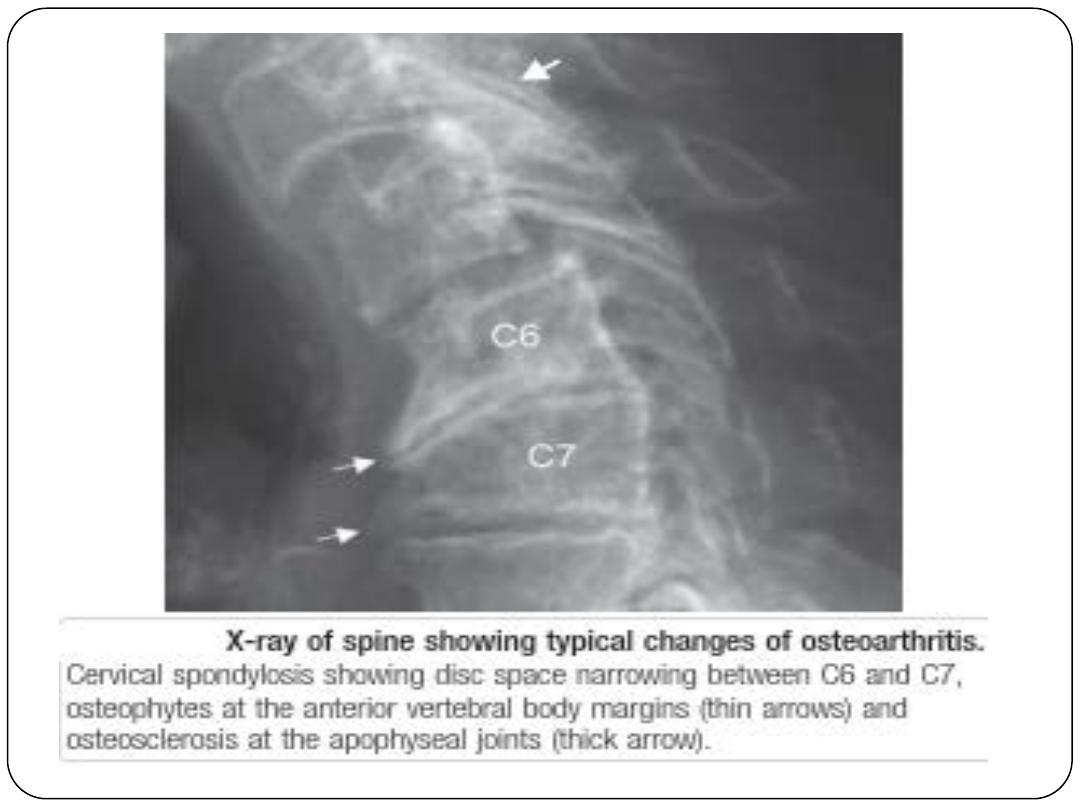

Spine OA

The cervical and lumbar spine are the sites most often targeted by OA,

where it is referred to as cervical spondylosis and lumbar spondylosis,

respectively. Spine OA may occur in isolation or as part of generalised

OA.

The typical presentation is with pain localised to the low back region

or the neck, although radiation of pain to the arms, buttocks and legs

may also occur due to nerve root compression. The pain is typically

relieved by rest and worse on movement.

On physical examination, the range of movement may be limited and

loss of lumbar lordosis is typical. The straight leg-raising test or

femoral stretch test may be positive and neurological signs may be

seen in the legs where there is complicating spinal stenosis or nerve

root compression.

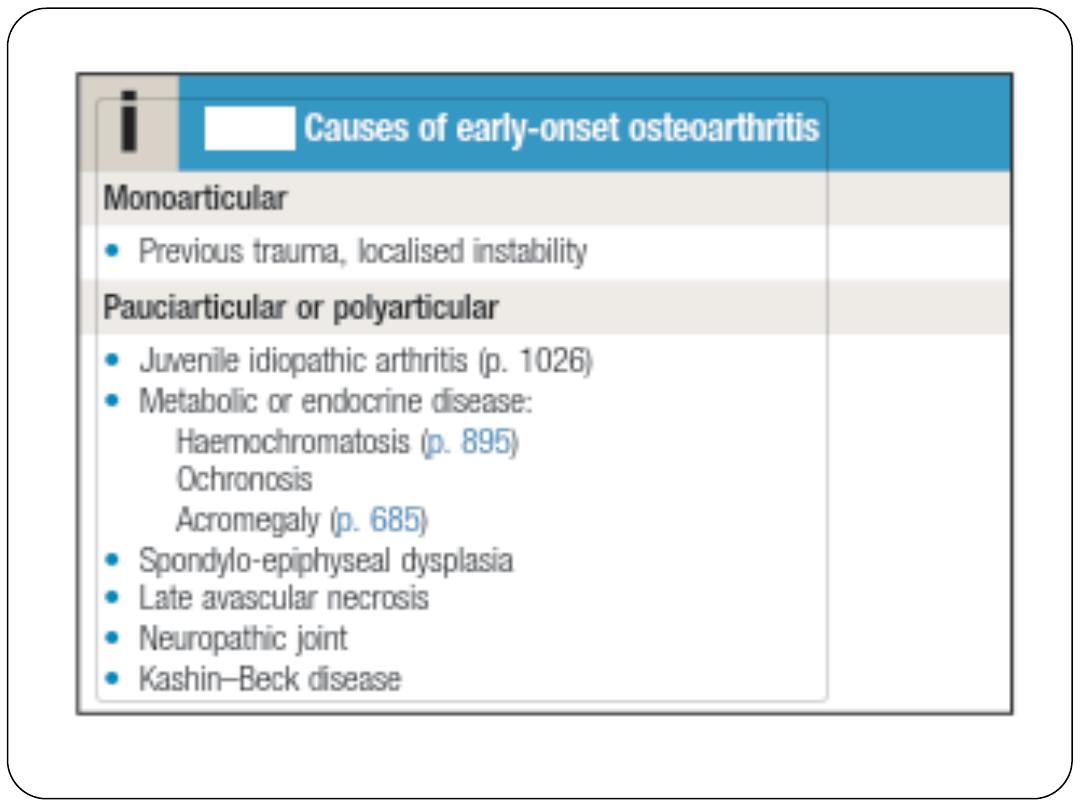

Early-onset OA

Unusually, typical symptoms and signs of OA may present before the

age of 45. In most cases, a single joint is affected and there is a clear

history of previous trauma. However, specific causes of OA need to be

considered in people with early-onset disease affecting several joints,

especially those not normally targeted by OA, in which case rare

causes need to be considered (Box).

Kashin–Beck disease is a rare form of OA that occurs in children,

typically between the ages of 7 and 13, in some regions of China. The

cause is unknown but suggested predisposing factors are selenium

deficiency and contamination of cereals with mycotoxin-producing

fungi.

Investigations

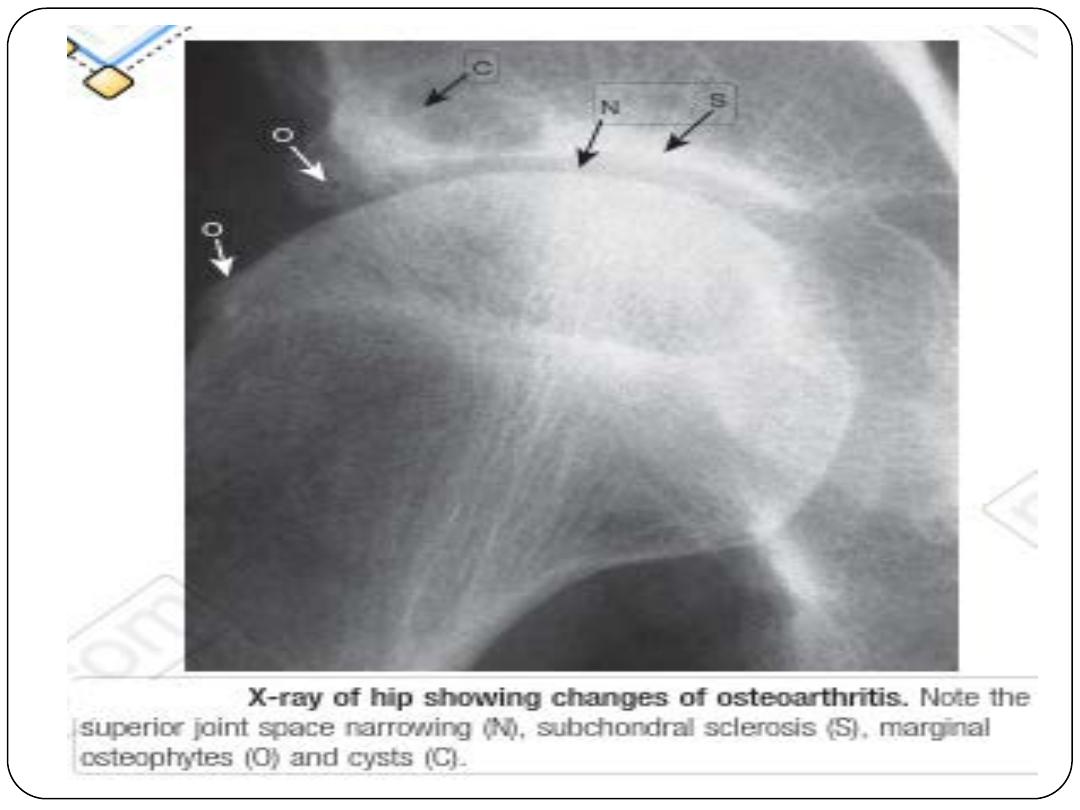

A plain X-ray of the affected joint should be performed and often this will show one or

more of the typical features of OA. In addition to providing diagnostic information, X-rays

are of value in assessing the severity of structural change, which is helpful if joint

replacement surgery is being considered. Non-weight-bearing postero-anterior views of

the pelvis are adequate for assessing hip OA. Patients with suspected knee OA should have

standing anteroposterior X-rays taken to assess tibio-femoral cartilage loss, and a flexed

skyline view to assess patello-femoral involvement. Spine OA can often be diagnosed on a

plain X-ray, which typically shows evidence of disc space narrowing and osteophytes.

If nerve root compression or spinal stenosis is suspected, MRI should be performed.

Routine biochemistry, haematology and autoantibody tests are usually normal, though OA

is associated with a moderate acute phase response.

Synovial fluid aspirated from an affected joint is viscous with a low cell count.

Unexplained early-onset OA requires additional investigation, guided by the suspected

underlying condition. X-rays may show typical features of dysplasia or avascular necrosis,

widening of joint spaces in acromegaly, multiple cysts, chondrocalcinosis and MCP joint

involvement in haemochromatosis, or disorganised architecture in neuropathic joints.

Management

Education

It is important to explain the nature of the condition fully, outlining the

role of relevant risk factors such as obesity, heredity and trauma. The

patient should be informed that established structural changes are

permanent and that, although a cure is not possible at present, pain

and function can often be improved.

The prognosis should also be discussed, mentioning that it is generally

good for nodal hand OA and better for knee than hip OA.

Lifestyle advice

Weight loss has a substantial beneficial effect on symptoms if

the patient is obese and is probably one of the most effective

treatments available for OA of the lower limbs.

Strengthening and aerobic exercises also have beneficial

effects in OA and should be advised, preferably with

reinforcement by a physiotherapist.

Quadriceps strengthening exercises are particularly beneficial

in knee OA.

Shock-absorbing footwear, pacing of activities, use of a walking

stick for painful knee or hip OA, and provision of built-up

shoes to equalise leg lengths can all improve symptoms.

Non-pharmacological therapy

Acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

(TENS) have been shown to be effective in knee OA.

Local physical therapies, such as heat or cold, can sometimes give

temporary relief.

Pharmacological therapy

If symptoms do not respond to non-pharmacological measures,

paracetamol should be tried.

Addition of a topical NSAID, and then capsaicin, for knee and hand

OA can also be helpful. Oral NSAIDs should be considered in

patients who remain symptomatic. These drugs are significantly more

effective than paracetamol and can be successfully combined with

paracetamol or compound analgesics if the pain is severe. Strong

opiates may occasionally be required. Antineuropathic drugs,

such as amitriptyline, gabapentin and pregabalin, are sometimes used

in patients with symptoms that are difficult to control but the evidence

base for their use is poor. Neutralising antibodies to nerve growth

factor have been developed and are a highly effective treatment for

pain in OA but they are not yet licensed for routine clinical use.

Intra-articular injections

Intra-articular glucocorticoid injections are effective in the

treatment of knee OA and are also used for symptomatic

relief in the treatment of OA at the first CMC joint. The

duration of effect is usually short but trials of serial

glucocorticoid injections every 3 months in knee OA have

shown efficacy for up to 1 year.

Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid are effective in

knee OA but the treatment is expensive and the effect short-

lived.

Neutraceuticals

Chondroitin sulphate and glucosamine sulphate have been used

alone and in combination for the treatment of knee OA. There is

evidence from randomised controlled trials that these agents can

improve knee pain to a small extent (3–5%) compared with

placebo.

Surgery

Surgery should be considered for patients with OA whose symptoms and

functional impairment impact significantly on their quality of life

despite optimal medical therapy and lifestyle advice. Total joint

replacement surgery is by far the most common surgical procedure for

patients with OA. It can transform the quality of life for people with

severe knee or hip OA and is indicated when there is significant

structural damage on X-ray. Although surgery should not be

undertaken at an early stage during the development of OA, it is

important to consider it before functional limitation has become

advanced since this may compromise outcome.

Patient-specific factors, such as age, gender, smoking and presence of

obesity, should not be barriers to referral for joint replacement.

Only a small proportion of patients with OA progress to the

extent that total joint replacement is required but OA is by far

the most frequent indication for this. Over 95% of joint

replacements continue to function well into the second decade

after surgery and most provide life-long, pain-free function. Up

to 20% of patients are not satisfied with the outcome, however,

and a few experience little or no improvement in pain. Other

surgical procedures are performed much less frequently.

Osteotomy is occasionally carried out to prolong the life of

malaligned joints and to relieve pain by reducing intraosseous

pressure. Cartilage repair is sometimes performed to treat focal

cartilage defects resulting from joint injury.

THANKs