IRON DEFICIENCY

ANEMIA

IDA

DR MOHAMED GHALIB

INTERNAL MEDICINE

TUCOM

OBJECTIVES

•

Prevalance of IDA

•

Metabolism & absorption of Iron

•

Iron stores

•

Pathogenesis of IDA

•

Causes of IDA

•

Features of IDA

•

Investigations of IDA

•

Treatments of IDA

Around 30% of the total world population is anaemic

and half of these, some 600 million people, have

iron deficiency. The classification of anaemia by the

size of the red cells (MCV) indicates the likely

cause.

Red cells in the bone marrow must acquire a

minimum level of haemoglobin before being

released into the blood stream. While in the marrow

compartment, red cell precursors undergo cell

division, driven by erythropoietin. If red cells cannot

acquire haemoglobin at a normal rate, they will

undergo more divisions than normal and will have a

low MCV when finally released into the blood.

The MCV is low because component parts of

the haemoglobin molecule are not fully

available: that is, iron in iron deficiency,

globin chains in thalassaemia, haem ring in

congenital sideroblastic anaemia and,

occasionally, poor iron utilisation in the

anaemia of chronic disease/anaemia of

inflammation.

Iron deficiency is the leading cause of anemia

worldwide. Although the presentation of

classic iron deficiency anemia is linked with a

microcytic anemia, early iron deficiency is

associated with a normocytic anemia.

Consequently, iron deficiency should be

considered in all patients with anemia, and

iron indices should be a part of the

evaluation of any patient with hypopro-

ductive anemia, regardless of the MCV.

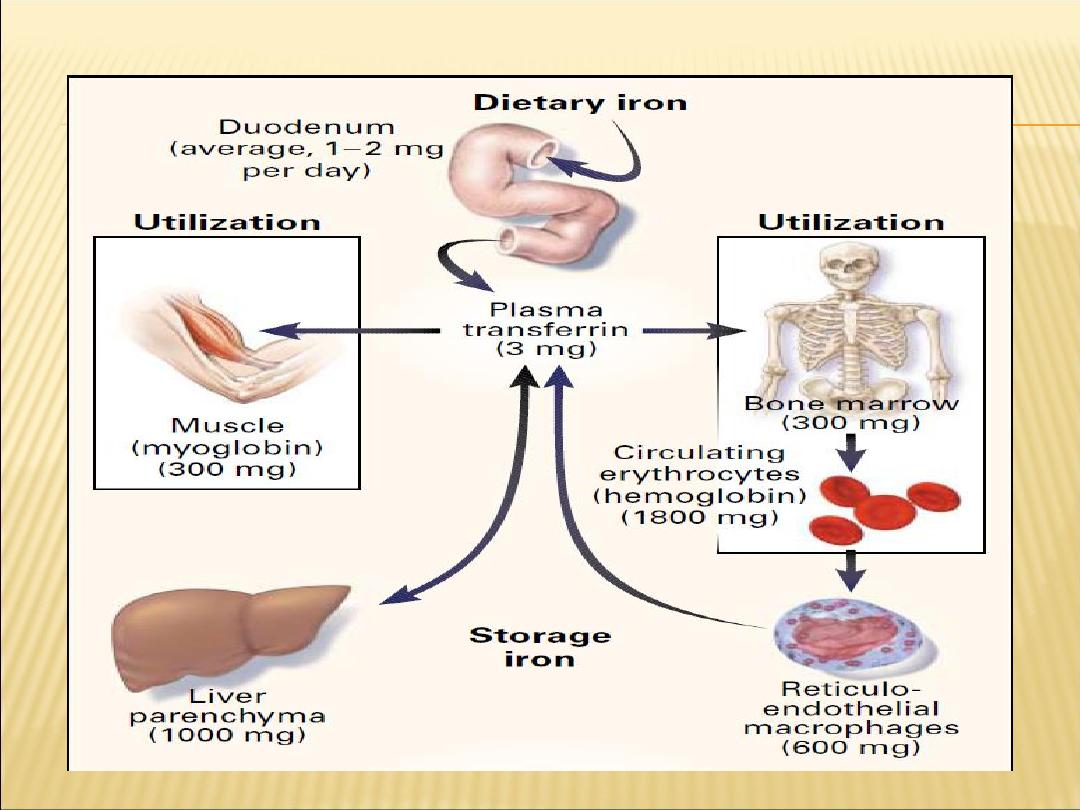

Iron is acquired in the diet from heme sources

(i.e., meat) and from nonheme sources (e.g.,

vegetables such as spinach).

Iron from heme is better absorbed than

nonheme iron.

Iron absorption is increased in iron deficiency,

hypoxia, ineffective erythro-poiesis, and

hereditary hemochromatosis.

Iron is absorbed from the proximal small

intestine; it is transported in the cell bound to

ferroportin and through the plasma bound to

transferrin.

Its uptake into the RBC precursors is mediated

through the transferrin receptor. Iron absorption

from the intestine is further regulated by hepcidin.

Iron outside hemoglobin-producing cells is stored in

ferritin. Men and women have total-body iron

concentrations of 50 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg,

respectively. Between 60% and 75% of the iron is

found in hemoglobin. A small amount (2 mg/kg) is

found in heme and nonheme enzymes, and 5

mg/kg is found in myoglo-bin. The remainder is

stored in ferritin, which resides primarily in liver,

bone marrow, spleen, and muscle.

The capacity for excreting iron is limited, and

iron overload occurs in patients with

excessive absorption from the

gastrointestinal tract (as a result of ineffective

erythropoiesis or congenital

hemochromatosis) and in those with chronic

transfusions. Iron overload leads to

increased iron deposition in these tissues

and secondary deposition in endocrine

organs, resulting in liver dysfunction,

diabetes, and other endocrine abnormalities.

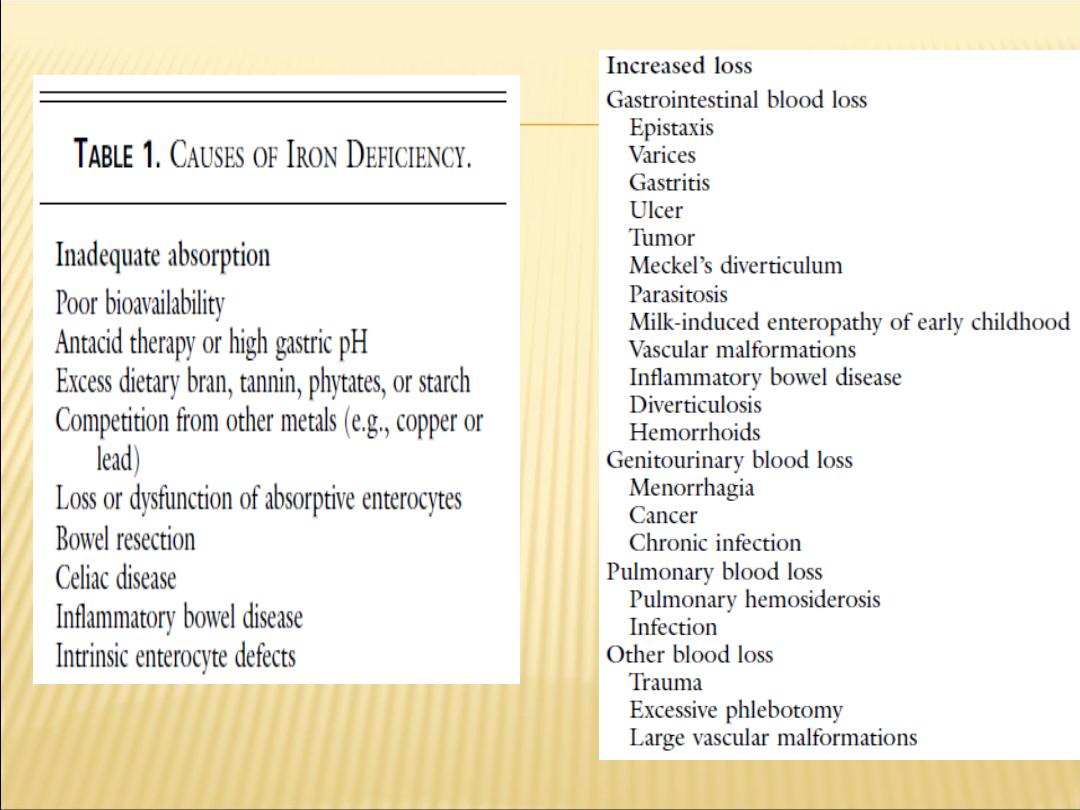

PATHOGENESIS OF IRON DEFICIENCY

1- Blood loss

Occult or overt GI losses, traumatic or surgical losses

2- Failure to meet increased requirements

Rapid growth in infancy and adolescence

Menstruation, pregnancy

3- Inadequate iron absorption

Diet low in heme iron

Gastrointestinal disease or surgery

Excessive cow

’s milk intake in infants

FEATURES OF IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Depends on the degree and the rate of

development of anemia

Symptoms common to all anemias:

pallor, fatigability, weakness, dizziness,

irritability

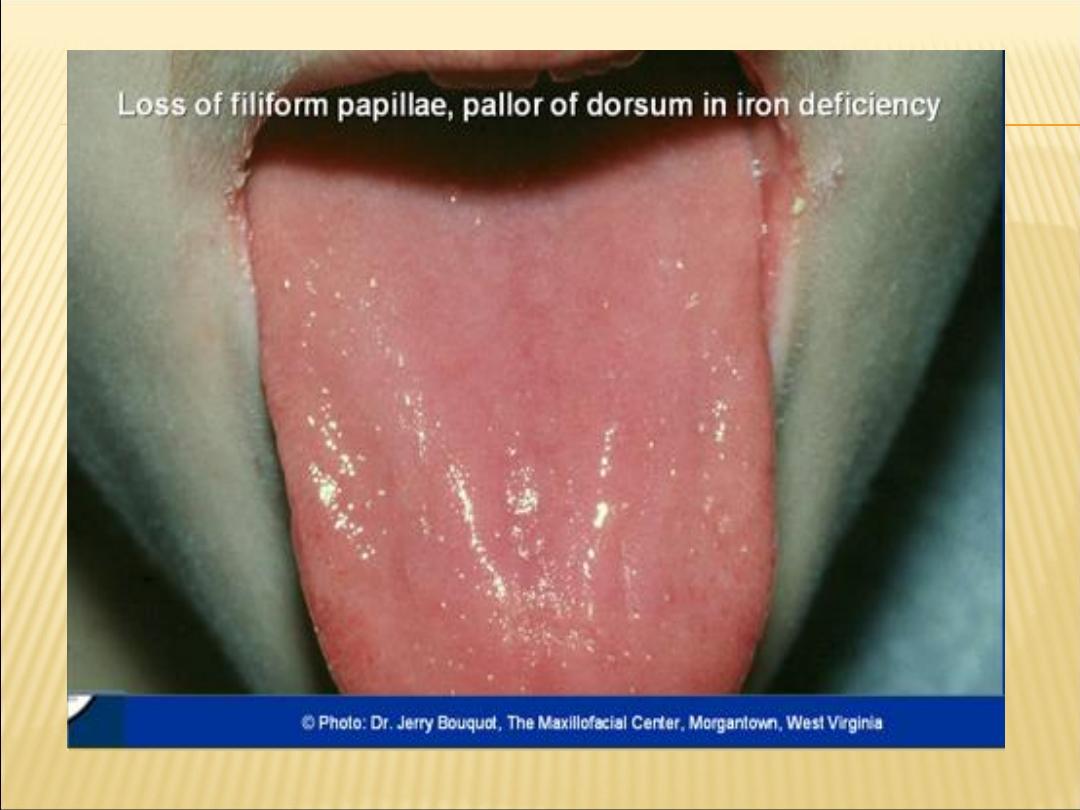

OTHER FEATURES OF IDA

Pagophagia - craving ice

Pica - craving of nonfood substances

e.g., dirt, clay, laundry starch

Glossitis - smooth tongue

Restless Legs

Angular stomatitis - cracking of corners of

mouth

Koilonychia - thin, brittle, spoon-shaped

fingernails

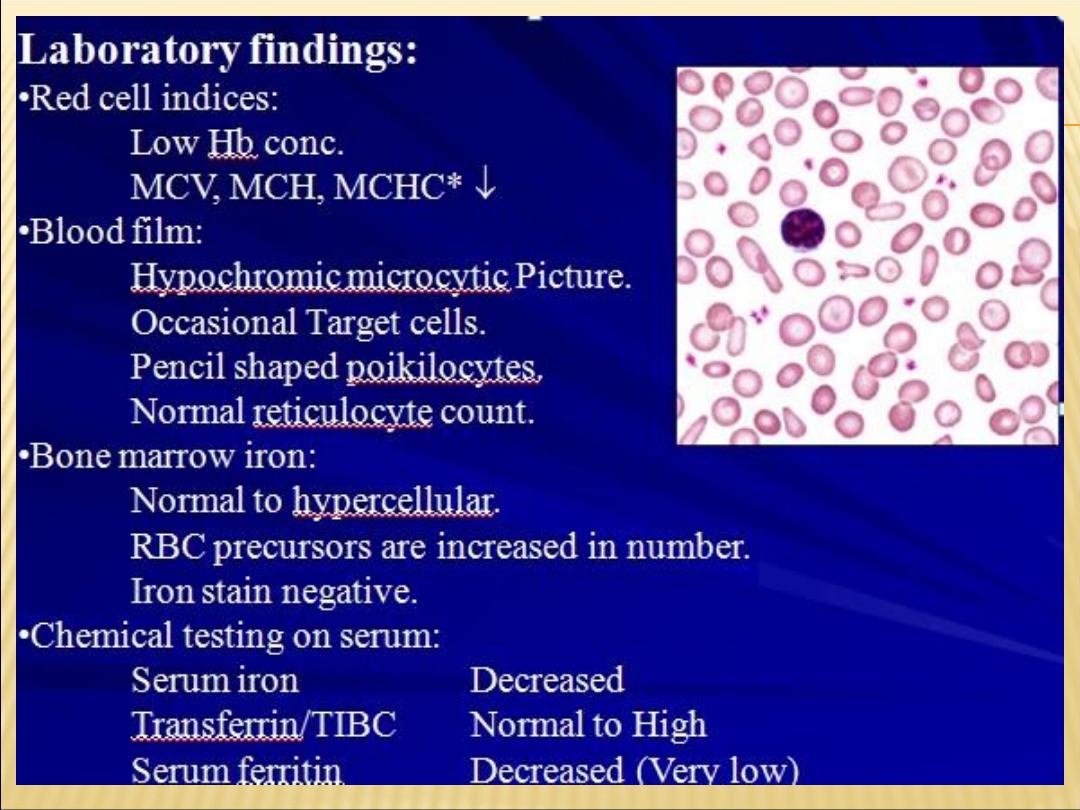

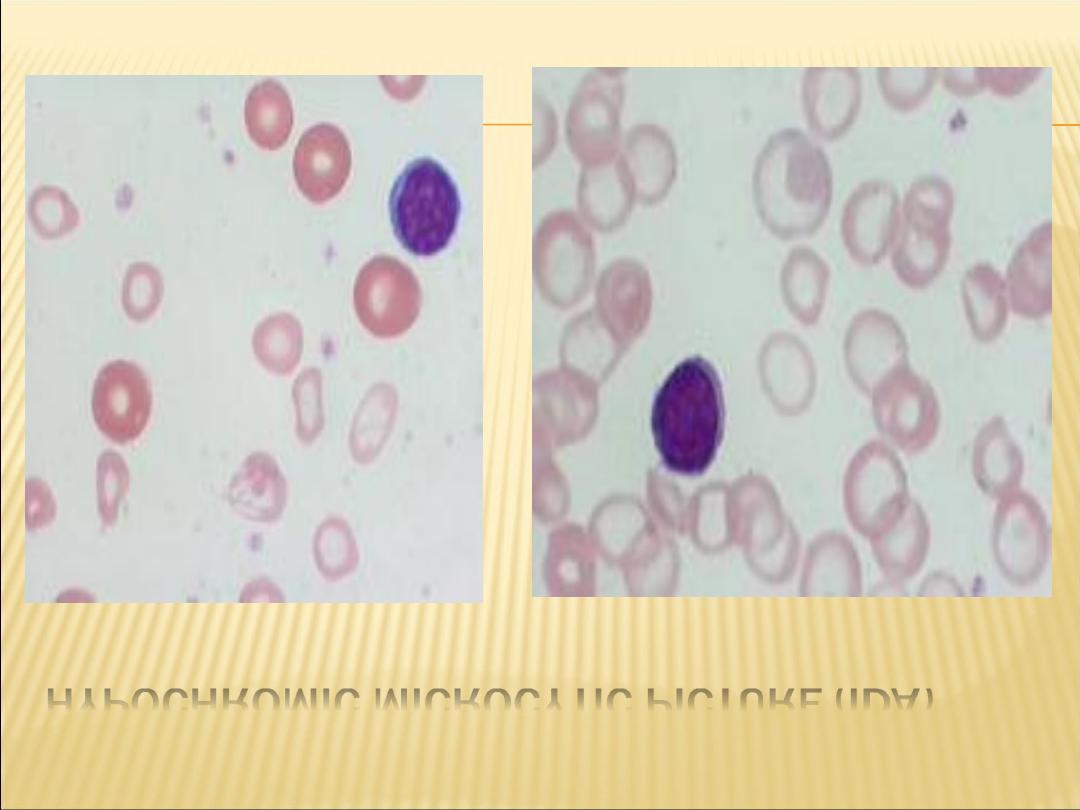

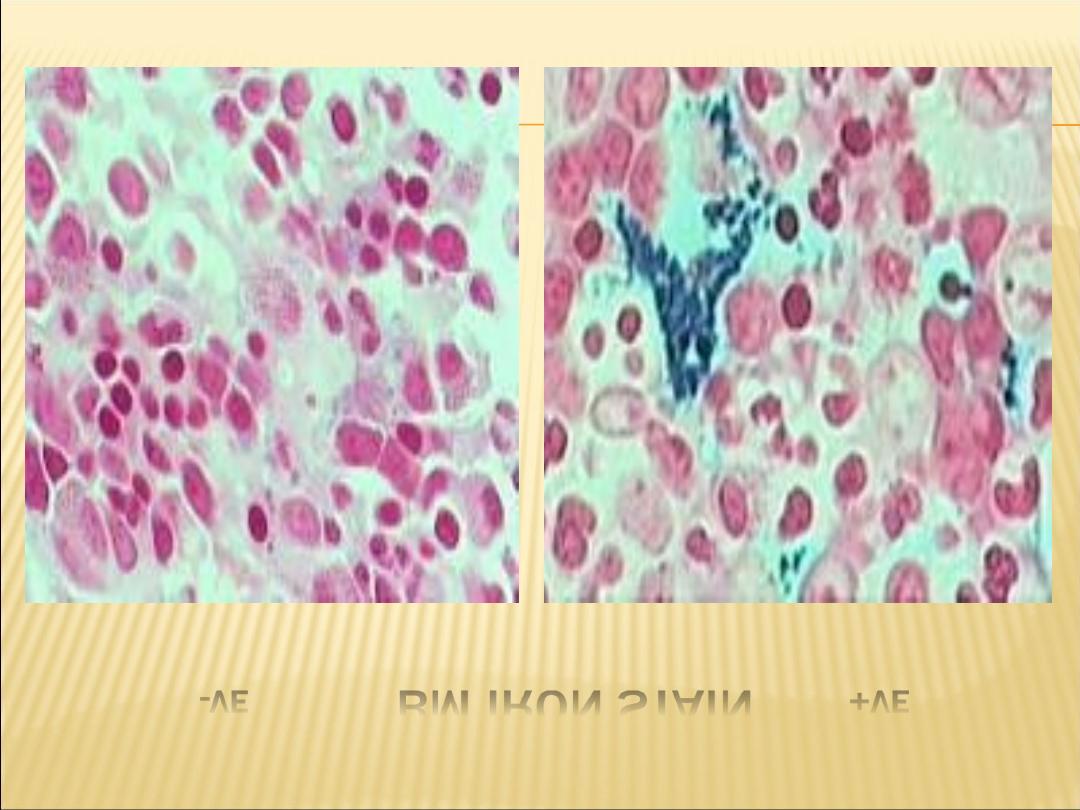

HYPOCHROMIC MICROCYTIC PICTURE (IDA)

-VE

BM IRON STAIN

+VE

TREATMENT

Oral iron supplementation, with administration

of ferrous sulfate or ferrous gluconate two or

three times daily, is the treatment for iron

deficiency. Patients should be educated

about the potential gastrointestinal side

effects, including diarrhea or constipation,

and some may benefit from a gradual

increase in the dose based on tolerance. Iron

should be administered for several months

after resolution of anemia to allow for the

reconstitution of iron stores.

In patients with malabsorption, a complete

inability to tolerate oral iron, or iron demands

that outstrip replacement with oral

supplements, parenteral iron may be

administered. The paren-teral administration

of iron, especially iron dextran, has been

associated with anaphylaxis. However,

newer preparations such as sodium ferric

gluconate, iron sucrose, ferumoxytol, and

ferric carboxymaltose are significantly safer.

All male patients and postmenopausal women

with iron deficiency require evaluation for a

source of gastrointestinal bleeding.

The haemoglobin should rise by around 10 g/L every

7

–10 days and a reticulocyte response will be

evident within a week. A failure to respond

adequately

may

be

due

to

non-adherence,

continued blood loss, malabsorption or an incorrect

diagnosis. Patients with malabsorption, chronic gut

disease or inability to tolerate any oral preparation

may need parenteral iron therapy. Previously, iron

dextran or iron sucrose was used, but new

preparations

of

iron

isomaltose

and

iron

carboxymaltose have fewer allergic effects and are

preferred. Doses required can be calculated based

on the patient

’s starting haemoglobin and body

weight. Observation for anaphylaxis following an

initial test dose is recommended.